The Hero Around the Corner

Remembering Lancaster pilot Lewis Johnstone Burpee on the 75th Anniversary of the Dambusters’ Raid

It’s springtime in the Glebe. May 14th to be exact. The sun shines with a new intensity. The breeze billows through the screen window of my office, wafting paper across my desk. It was a particularly tough winter but the pain of it is soothed by a fine evening. Tonight is one of those evenings in which it is very good to be alive.

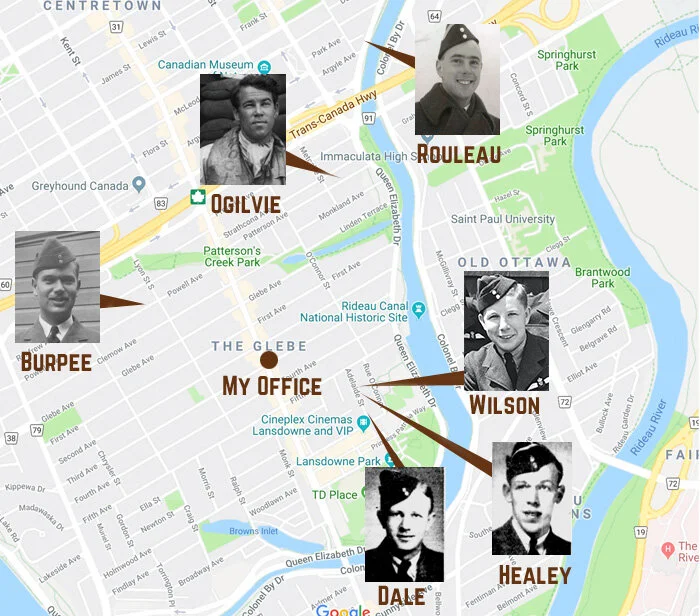

My office is on the second floor of a small building at the corner of Third Avenue and Bank Street in an area of Ottawa known as the Glebe. Bank is what you would call the high street in England, the main street in North America. It draws down from the north near the Parliament Buildings and continues on uninterrupted until almost the St. Lawrence River, 60 miles to the south.

I suspect that Bank in the Glebe is much the same as it was 75 years ago in May of 1943—save for the nature of the businesses, the highfalutin quality of our new-age restaurants and their fancy outdoor terraces and the style of the automobiles. Today, pricey Glebe housing means that the people of the Glebe are uniformly in a higher income bracket, but in ‘43, the Glebe had three distinct layers—the wealthy, the middle class and the working class. I have lived in the Glebe now for 46 years, all of that time in former working-class neighbourhoods. It has been a very happy and welcoming community. A very close-knit one.

Over the past decade, researching and publishing stories about Canada’s aviation heritage, I have come across a few that have intersected with the small community I know so well and love so much. It’s not that I have gone looking for stories of men in my neighbourhood; they just arrive at my doorstep so to speak. These young men are just a fraction of the men and women from the Glebe who served during the war, yet in the small sampling of six airmen that I know of, one was a Battle of Britain fighter pilot and Great Escaper, one was at the Siege of Malta, and one was a Dambuster. It is a testament to the pivotal nature and the emotional power of these four events, that major motion pictures were made of them—Malta Story (1953), The Dam Busters (1955), The Great Escape (1963), and Battle of Britain (1969).

Directly across from my home on Adelaide Street (about three blocks from my office) lived a young man named James Wilson, a Bristol Beaufighter pilot. He disappeared with his navigator on an anti-shipping operation in November of 1942. He has no known grave. A few doors down Adelaide, at number 21, lived Wilson’s cousin, a young man named Harold Healey. He too died on Bomber Command operations with 207 Squadron, RAF on 9 April 1943. Still further down the street, a 21-year-old Warrant Officer and Spitfire pilot by the name of Ken Dale was lost in late 1944 on operations with 249 Squadron—the same squadron that included such fighter pilot luminaries as Flight Lieutenant George “Screwball” Beurling, Wing Commander Percy “Laddie” Lucas, and Squadron leader Robert “Buck” McNair.

Five blocks north of my office, just to the east of Bank Street on Patterson Avenue, is the former home of Flying Officer “Skeets” Ogilvie, a Battle of Britain hero and the last man to escape from the tunnel known as Harry in the Great Escape. Four blocks beyond that, on Queen Elizabeth Drive stands the home of a bright young man by the name of David Francis Gaston Rouleau, a Spitfire pilot who flew from the deck of HMS Eagle in an attempt to make it to Malta. After a 400-mile flight, Rouleau was attacked and shot down just a few kilometres from that tiny besieged island. He too has no known grave.

If you live in a neighbourhood that was built before the war, there are the ghosts of young men around you—the phantoms of boys who grew up on your street or around the corner. Who went away and would never come home. Adelaide Street is only one block long, but in 1943 and ’44, grief must have hung black and heavy over her rooftops. Fear also lived here. The fear of families whose boys and girls were fighting in some theatre of war somewhere. The constant gnawing dread of families who prayed that the telegram boy would cycle past to some other door.

This evening, I paid a short walk-by visit to the former home of another young man from the Glebe whose life held great promise before the war took everything from him and his family. The young man’s family has long since moved away, but the memory of their loss will forever dwell in this house, recognized or not. The house is on a wide shady avenue in the most well-to-do area of the Glebe. The family was one of means. The young man’s life was one of privilege and opportunity. His name was Lewis Johnstone Burpee.

I took a break from writing this evening and strolled five blocks down Bank Street, turned west into the sun onto Powell Avenue and found Lewis Burpee’s childhood home, just a block and a bit to the west. In a neighbourhood overwhelmed with fancy and expensive renovations, 111 Powell Avenue looks much the same as it did 75 years ago—a typical upper middle-class brick pile that the Glebe is known for. I stood for a while and thought about the fine evening and the warm lowering sun and the 27,000 such evenings this beautiful young man never got to see and enjoy. I felt exceedingly humbled and sad. I stood there for about a minute, then slowly shook my head, snapped a photo and walked back to my office to write down my thoughts. Photo: Dave O’Malley

A photo of Lewis Burpee after his 1940 graduation from Kingston, Ontario’s Queen’s University with a Bachelor of Arts degree in history, politics and English. Photo: A.R. Timothy

Related Stories

Click on image

A photograph of Course 31 (21 June–30 August 1941) at No. 9 Service Flying Training School at RCAF Station Summerside, Prince Edward Island. As they still wear their white cadet hat flashes and no pilot’s brevet, this was before their graduation. Burpee (standing at far right) started his flying training on Fleet Finches at No. 13 Elementary Flying Training School at St. Eugene, about 60 miles east of his Ottawa home. Most men who earned their wings at No. 9 SFTS went on to single seat fighters or maybe twin-engine fighter-bombers, but Burpee ended up as a Lancaster pilot. Also in this course is the famous Second World War Canadian fighter ace John McElroy, who fought for the Israeli Air Force in 1948 in their War of Independence. On the final days of that war, McElroy shot down two Royal Air Force Spitfires. Photo: The Canadian Virtual War Memorial

Shortly after receiving his wings and being promoted to Sergeant Pilot in September of 1941, Lewis Johnstone Burpee took leave for home in Ottawa. Here we see him neatly turned out for the folks at his family cottage along the Rideau waterway system. He was just 23 years old. Photo: The Canadian Virtual War Memorial

Lewis Johnstone Burpee was one of just 19 Avro Lancaster pilots of 617 Squadron who took part in one of the most daring and technically complicated bomber raids of the war—Operation Chastise, or as we all have come to know it, the Dambuster Raid.

In the seventy-five years since the night of 16–17 May 1943—the night of Operation Chastise—the events that transpired on that moonlit spring night have been made into feature films, documentaries, novels, non-fiction books, magazine articles, dramatic paintings, computer games, marches and comic books. For all of you who read this, there is not much one can say to add to the reportage of this stunning attack deep inside Germany on targets long thought to be unassailable.

On that dark night, lit only by the moon, 133 very young men of 617 Squadron took off in 19 specially modified Avro Lancaster bombers, formed up and flew extremely low over the English Channel across the Dutch coast. Having trained for months to deliver a very special weapon, the young men were headed for a date with destiny. The aircraft were to fly low, beneath radar coverage, navigate deep into Germany, locate and attack a series of massive dams on tributaries of the Ruhr River. Behind each of these dams, the Möhne Dam, the Sorpe Dam, the Eder Dam and the Ennepe Dam, were massive reservoirs of water which, it was hoped, would flood factory sites downstream and bring much of Germany’s industrial production to a standstill. The dangers of flying low over heavily-defended German occupied Europe at night meant that not all of them would make it to their targets.

The attacks would be carried out using a special explosive device which, when released from a Lancaster bomber at exactly 60 ft AGL, at exactly 240 mph and at a specific distance from the reservoir-side face of the dam, would fall to the water and then bounce like a skipping stone, in decreasing bounces, until it fell exactly at the face of the dam. The bombs would then sink down the face of the dam to a specific depth where a hydrostatic sensor would detonate the bomb like a depth charge. And like a depth charge, the bomb would use the power of compressed water to deliver a devastating blow deep beneath the surface, weakening the dam’s structural integrity. The massive weight of the stored water would then breach the weakened dam wall and roar down the valleys, flooding industrial complexes downstream.

If 617 Squadron crews made it through to their targets, they faced one of the most dangerous attack scenarios in bombardment history—at extreme low level, at night, at specific heights, speeds and distances against heavily defended targets. Illustration: Dave O’Malley

The squadron was made up of hand-picked crews under the leadership of the charismatic 24-year-old Wing Commander Guy Gibson, a veteran of over 170 bombing and night-fighter missions. These crews included RAF personnel of several different nationalities, as well as members of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), who were frequently attached to RAF squadrons under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. The squadron was based at RAF Scampton, about 5 mi (8 km) north of Lincoln. Most of the crews found their targets and, facing heavy flak and cannon fire from the dams’ batteries of anti-aircraft guns, they pressed home their attack, with only the moon to guide them.

Before being selected by Wing Commander Guy Gibson for the elite 617 Squadron, Lewis Burpee (third from right) was with 106 Squadron, another elite unit that was, at the time, also commanded by Gibson. Here we see him with members of his 106 Squadron Lancaster Crew at RAF Syerston in the early morning after a night op on 18 January 1943. Four months later, Burpee would be dead. Those of his 106 Squadron crew who volunteered for a second tour stayed with him when he transferred to 617 Squadron, they are (Left to Right): Gordon “Gordie” Brady, Rear Gunner; William “Ginger” Long, Air Gunner; and Guy “Johnny” Pegler, Flight Engineer. Photo: The Canadian Virtual War Memorial

Burpee (second from right) and other 617 Squadron airmen pose with squadron mascot and Wing Commander Guy Gibson’s Labrador puppy with the cringe-worthy name of “Nigger”. On the day the Dambusters were to launch against the Ruhr dams, the dog was struck and killed by a car. Nigger was buried at midnight on the grounds of RAF Scampton while Gibson was leading the raid. The dog, with its ridiculously inappropriate and racist name, had a starring role in the later motion picture made of the Dambusters Raid. In this photo, I can’t help but notice the change in Burpee’s physical appearance. He has lost considerable weight and looks drawn and tired, wrought no doubt by the strain of a 32-op tour with Bomber Command, followed by hard training for the upcoming raid under dangerous low-level night conditions. Photo: eBay

The caption for this photograph on the Canadian Virtual War Memorial reads: “P/O Leonard George Weller (Wireless Operator) No 106 Squadron 1943 with Lewis Burpee (right)”. Looking at this, there are some things that make me question this caption. Weller is clearly a Sergeant in this photo and it seems that Burpee has lost his Sergeant’s stripes. Since Burpee was made a Pilot Officer after he transferred to 617 squadron at RAF Scampton, this may in fact be post 106 Squadron. Weller, another Canadian, was Burpee’s Wireless Operator in his 617 Dambusters crew and was killed with him in Holland. The grassy knoll on which they stand is similar to that seen in other crew photos taken at Scampton. Photo: The Canadian Virtual War Memorial

Sergeant Lewis Burpee (left) with members of his 106 Squadron crew including his Flight Engineer Guy Pegler (right) and his Rear Gunner Gordon Brady (second from right). I can’t identify the fourth man. Photo: The Canadian Virtual War Memorial

Pilot Officer Lewis Burpee, DFM was the commander of Lancaster “S” Sugar (AJ-S, ED865), assigned to the final wave of five Lancasters, which was to fill in as a mobile reserve in the event of losses or failure to breach the dams. Burpee took off a little after midnight on the 17th and headed across the North Sea towards Holland. While over Holland, near the Luftwaffe airfields at Eindhoven and Gilze-Rijen, his Lancaster came under heavy anti-aircraft fire and was caught by searchlights. It is not known for certain that he was hit by flak or whether he struck the ground trying to get under the blinding searchlight beams. Regardless, Burpee’s Lancaster hit the ground near the perimeter of Gilze-Rijen airfield. His “bouncing bomb” payload, code-named Upkeep, exploded on contact.

Only three of the bodies of “S” Sugar’s crew were ever identified—Burpee’s, and the two other Canadians in his crew, Rear Gunner Gordie Brady and Wireless Operator Leo Weller. The remains of the others would be buried in a mass grave—Flight Engineer Guy Pegler, Navigator Thomas Jaye, Bomb Aimer Jim Arthur and Air Gunner William Long.

When the last Lancaster touched down at RAF Scampton on the morning of May 17th, 617 Squadron assessed its losses and its successes. Both were considerable. Of the 19-participating aircraft, 8 were shot down including Burpee’s. Of the 133 men involved, 53 were killed. Of the 53 killed, 15 were Canadian. Of the 15 Canadians, one was from the Glebe. Two of the target dams were breached and one damaged. There was one Victoria Cross (Gibson), as well as five Distinguished Service Orders, 10 Distinguished Flying Crosses and four bars, two Conspicuous Gallantry Medals, and eleven Distinguished Flying Medals and one bar given out for service on that one night alone. 53 missing-in-action telegrams were later sent to families from New Zealand to Canada. One came to 111 Powell Avenue. None of those missing-in-action telegrams was ever followed up with news of survival.

The telegraphed news of the raid made it to the hometowns of all of the crews before the telegrams did. That very night, the Ottawa Evening Journal carried a front page story about the raids. In a tragic coincidence, it also carried a story about Burpee’s award of a DFM and his marriage to an English girl. The piece on Burpee began with “The Air Ministry on London today announced the award of the Distinguished Flying Medal to Pilot Officer Lewis J. Burpee, 25, son of Lewis A. Burpee, general manager and vice-president of Charles Ogilvy Limited, and Mrs. Burpee, 111 Powell. “That’s certainly good news” said Mr. Burpee when informed of his son’s decoration by the Journal.” For a day or so, the Burpee family felt comforted with the knowledge that Lewis was safe in England, happily married and highly experienced. Given the secrecy of the raid, it is doubtful that they had any idea their son was part of the historic event. That would change the next day.

Burpee’s father, who was the General Manager of Ogilvy’s Department Store in Ottawa, was a pillar of the community, and as such his son was considered somewhat of a local hero. Still a Sergeant Pilot when he received the decoration, the story of his award of the Distinguished Flying Medal came out after he was promoted to Pilot Officer at 617 Squadron. In a particularly unfortunate twist of fate, the story was published in the Ottawa Evening Journal on 17 May, the day of the Dambusters raid. In the very same issue of the paper was the headline Great Ruhr Dams Smashed! and a brief story of the previous night’s raid. Sadly, the family had yet to be informed of the death of their son. Photo: The Canadian Virtual War Memorial

A letter to Burpee’s parents a month after the Dambusters Raid from Squadron Leader H.F. Davidson, the RCAF Chaplain for both 106 and 617 Squadrons, implies that his bride Lillian is pregnant with their child and wants to join them in Canada. His words to Burpee’s parents state “Lillian says that she is waiting for an exit permit so that she can go out to you in Ottawa. I hope she is successful. It is very hard on her in her condition and I’m sure it would be some comfort both for you and her if you could be together just now.” Lewis Johnstone Burpee Jr. was born on Christmas Eve of the same year, seven months after his father was killed. He was born here in Ottawa and quite possibly lived at 111 Powell Ave. Photo: The Canadian Virtual War Memorial

Burpee’s wife Lillian wrote to his parents’ family, asking to join them in Ottawa for the birth of their grandchild. She sought an exit permit to travel by ship to Ottawa, where she lived with the Burpees until the birth of Lewis Johnstone Burpee Jr. on Christmas Eve 1943. There was no doubt great sadness at 111 Powell that Christmas day, but it would be tempered by the bittersweet arrival of the baby.

It has been 75 years since handsome Lewis Burpee, son of a respected Ottawa business man and Glebe native, died in Holland. His son would grow up in his family home until his mother remarried in 1951, becoming Mrs. C. Elliot Kerr. The love that was felt by Lewis’ parents for their daughter-in-law was demonstrated at her wedding when she was “given in marriage” by Lewis Burpee’s father. In another coincidence, Lillian Elliot’s new home was near the corner of O’Connor and Lewis Streets. I’m sure, despite her happiness, she thought of her brave first husband every time she looked up at that street sign.

As I finish up this story, it’s May 16th, I hear the bustle of Bank Street through my open window—the voices of men and women at the Starbucks patio below me, the happy shrieks of young girls leaving the dance academy across the street, the footsteps of Eric my postman coming up the stairs—all living a charmed life here in the Glebe. 75 years ago this very day, young Lewis Burpee walked towards the black outline of a Lancaster in the heavy gloom of a Lincolnshire night. The terrible stress of the upcoming mission lay like a crushing weight on his shoulders, heavier now that Lillian announced she was pregnant.

The sad truth is he would never see another sunrise again. Nor the shady elm-shaded streets of the Glebe.

But his son would.

Dave O’Malley

This simple map demonstrates the locations of the homes of some of the heroes that grew up in my neighbourhood. These men are just the ones I have come across in my research of disparate stories. There most certainly are many scores of others in the area covered by this map. However, in this small sampling, we have an extraordinary representation of some of the most famous and pivotal events and campaigns of the war—a Dambuster pilot, a Battle of Britain pilot and Great Escape participant, a Spitfire pilot lost during aircraft carrier resupply of Malta, a Coastal Command Beaufighter pilot lost at sea and two men lost on Bomber Command night operations.