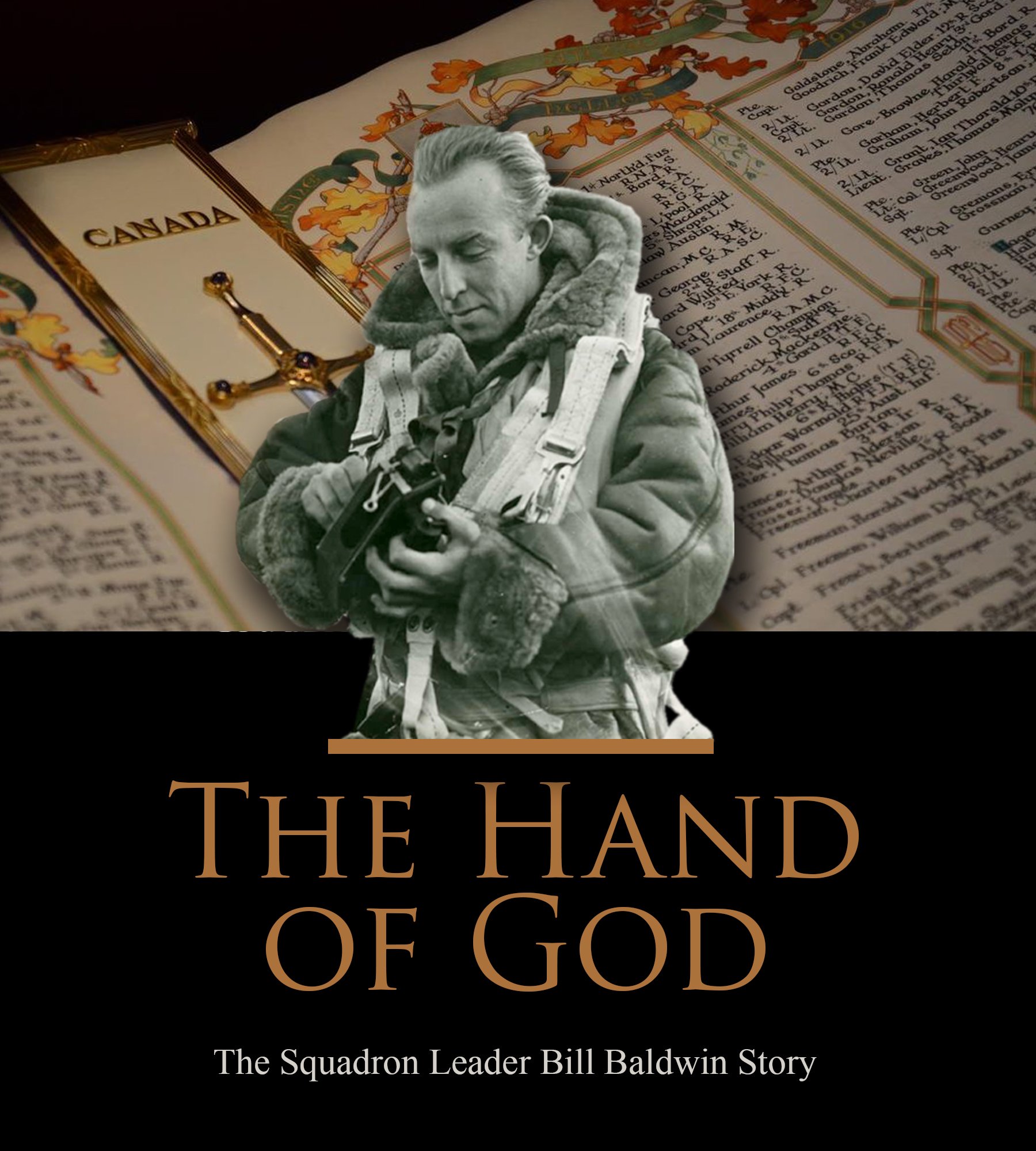

THE HAND OF GOD

The German town of Haldensleben astride the Ohre River and the narrow cut of the Mittelland Canal, is thirty kilometres northeast of the city of Magdeburg, the industrial and political capital of the German state of Saxony-Anhalt. Here, on many nights during the final years of the Second World War along the proscenium of the horizon there could be seen the red glow of fires, the silent blue sweep of searchlights, flak bursts, streams of tracer and burning airplanes — over Magdeburg to the southeast, Brunswick to the west, or Wolfsburg to the northwest, depending on the night. Overhead Haldensleben on some of those nights could be heard the dead set drone of hundreds of Bomber Command aircraft resignedly moving on towards Berlin or staggering home harried by night fighters.

Despite the night horizons, the harsh reality of war rarely came to Haldensleben in 1943. Most of the young men were gone to the east, lost to North African failures or at risk in Italy. Darkened army trucks rumbled through town and supply locos panted in the rail yard, but the town was rarely visited by the horrors of total war. Despite this distance, 15-year old Ernst Heuer never slept the sleep of a teenager.

Before going to bed on the night of August 23rd, the Heuer family had listened to a radio broadcast which gave them a warning that a raid on Berlin was expected that night. These warnings heightened his senses and he had trouble sleeping. Around 11:30 p.m., the bombers came. The sounds grew steadily from the west, moving like death in the darkness in the direction of Berlin, drifting on the southwesterly wind. Heuer was at the window, craning towards the night sky, terrified and entranced. The night was dark below and above him, the moon in its last quarter, the houses hiding behind drawn curtains. To the north tracers played silently, arc against arc, their sounds inaudible beneath the foreboding weight of thousands of Merlin and Hercules engines. It was strange how the massed sound had a quality like silence. He knew that once they passed, they would be back as they each found their way home

At 3 a.m. local time, Heuer witnessed a bright flash on the northern horizon in the direction of the villages of Satuelle and Born. It was followed quickly by a distant boom that he both heard and felt. He pulled in from the window and his mind raced thinking about what he had just witnessed. Shortly after sunrise, with the sounds of the living returning to the streets of Haldensleben, young Heuer left his house on his bicycle and called on his two friends Gustav and Jochen Molle. All had heard the explosion in the night and together they pedalled in the direction of Satuelle, towards a thin pall of greasy smoke rising some ten kilometres away. The crash site was north of Saturelle in a wooded area near the village of Dorst. They were the first Germans to arrive at the scene. Boys should not have to see what they saw.

There, as they stood next to their bicycles, eyes as big as saucers, lay the smouldering remains of an aircraft — clearly enormous and definitely not German. The forward section of the enemy bomber was completely destroyed — burned, twisted, broken, much of it melted from the fire. The rear fuselage of the aircraft, aft of the wing was untouched by the flames, a huge enemy roundel painted on its rippled and collapsed flank. Perhaps they did not know the name of their enemy’s aircraft, but there lay the mortal remains of a Handley-Page Halifax II heavy bomber of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

A factory-fresh Merlin-powered Handley Page Halifax II HR918, G for George, the same aircraft seen by Ernst Heuer and his friends. The aircraft is so fresh in this photo that it has yet to receive its 405 Squadron LQ-G codes. Image via worldwarphotos.info

The rear gunner, still strapped in his position in the tail of the bomber, clearly had died of cannon or machine-gun fire before the crash. Despite the heat of the August morning, he wore a heavy leather flying suit and boots. His documents included a photo of his girlfriend. The boys could see the blackened bodies of four airmen — burned, charred and grouped together near a hatch. There was another body that was not burned near the untouched rear fuselage. All around them lay machine gun ammunition and twisted metal.

Soon other citizens and small children gathered, standing and staring until the authorities came and chased them away. There were six bodies found in the wreck. The body of a seventh airman was found several days later, hanging from his parachute in a dead oak tree in the forest. His name was Squadron Leader William Henry Baldwin, DFC. He lived around the corner from where I live today and like me, he was a graphic designer, though back then the job was known as a commercial artist.

The Hanging Man

Behind the anonymity and obscenity of his swollen body dangling from his parachute shrouds in a dead tree far from home in a land of hate and horrors, I found a story of a young man to whom Canada owes much gratitude. Of course, the sacrifice of his life in the skies over nighttime Germany is foremost, but it is what young Bill Baldwin did before the war that makes his story so interesting and poignant and his legacy so lasting.

But, I am getting ahead of myself.

Bill Baldwin was born on January 10, 1910, long before any of the other members of his Halifax bomber crew. He was the first born son of Clayton James Baldwin and his wife, the former Helena Meagher. They named him William Henry Baldwin, after Clayton’s father of the same name. In the end Billy would become the older brother to three brothers (Clayton, James and Charles) and two sisters (Katherine and Naida).

The family lived at 182 Fifth Avenue in a leafy suburb of Ottawa called the Glebe. Their red brick home was one of the earlier homes in the Glebe and looked more like a farmhouse than the other working class structures and row houses of the neighbourhood. They were a god-fearing Roman Catholic family and attended the newly-built Blessed Sacrament Church around the corner where Clayton was a member of the Holy Name Society.

182 Fifth Avenue, the red brick childhood home of Bill Baldwin, looks much the same today as it did when he lived there in the 1920s and 30s. Photo via Google Maps

Clayton Baldwin worked as the chief mechanic at the Government Printing Bureau which, back then, stood on the present-day site of the National Gallery of Canada. He was responsible for the maintenance of printing presses, paper guillotines, binding machines and other mechanical equipment. Young Bill grew up around printing inks, books, pamphlets, bindery and the world of commercial art.

Related Stories

Click on image

Clayton Baldwin, Bill’s father worked at the large Government Printing Bureau on Sussex Drive. The building was demolished after the “Queen’s Printer” moved across the river to Hull, Quebec in the late 1950s. The beautiful National Gallery of Canada now occupies the site.

Bill attended St. Matthew’s Separate School and then completed his secondary education at Glebe Collegiate Institute where he studied something called physiography — the study of the physical patterns and processes of the earth — as well as history and literature. He developed an interest in penmanship and calligraphy. Upon graduating in 1928, he took an office job with Metropolitan Life insurance company, working from their head office at the corner of Bank and Wellington streets. Office work was not his style and after a year he found a new job where he could exercise his creative talents — as a civilian employee of the Royal Canadian Air Force’s Photographic Section at the Jackson Building on Bank Street, a few blocks south of his previous place of employment. According to his attestation papers he was involved in all aspects of the work — sketching, cartooning, hand lettering, poster design, book covers, and even aerial photography. As much as he loved the work, a policy decision was made in 1932 to dispense with all the civilian employees of the Photo Section, and he was forced to leave.

And that’s when his story gets interesting.

The Canadian Book of Remembrance

Colonel Archer Fortescue Duguid, DSO, a First World war veteran and the Director of the Historical Section of the Department of National Defence (and sometime excoriated writer of the single volume of Canada’s official First World War history) put forth the idea to create a Book of Remembrance to commemorate all 66,655 Canadians who died while in the military service of Canada in the First World War. It would not be merely a list of the names, but rather, as Walter B. Bowker of the Ottawa Citizen would later write as the work got under way:

“a fitting expression of Canada’s sentiment toward her war dead and a treasure to hand down to posterity as one of the most beautiful examples of modern illuminated manuscript in the world today…. It will contain the names of all members of Canadian forces and all Canadians who served in other Allied forces throughout the Empire who lost their lives from war causes between August 4th 1914 and April 30th 1922, the day of final demobilization of the C.E.F.” [Canadian Expeditionary Force]

To design the illuminations in the book that would indeed make it one of the finest examples of the art form, a committee of six leading experts was put together to choose the chief designer. The committee reviewed unsigned examples of the work of several Canadian heraldic artists. The winning submission was that of James Purves of London, Ontario. Purves’ submission was in the form of a mock-up of the book depicting his design for visual treatment and overall concept.

In 1932, Purves set up a studio in the National Research Council’s brand new offices on Sussex Drive adjacent to Rideau Falls — fitted out with special tables, light screens, lamps, magnifying devices and humidifying apparatus to keep the hand-made vellum sheets supple.

While setting up the studio facilities where the work was to be carried out, Purves began looking for assistants, for the task ahead was far beyond the capacity of a single man. Most of his team were chosen from the Ottawa area and Bill Baldwin, after being laid off from the Photographic Section, applied and was accepted for a position. Baldwin must have submitted examples of his penmanship and calligraphy skills, for he was selected for the most daunting task of all — the inscription of all 66,655 names in alphabetical order by year of death including rank and military unit. To keep “the hand” absolutely identical from the first to the last of the eventual 600 plus pages, the work would be carried out by one person. The shear amount of research and collation is staggering — get one name out of order, make a spelling error or get one army unit wrong and the work for that page or year’s section would have to begin again.

Baldwin’s methodical and precise work would take him a staggering five years to complete. Any spelling mistake, calligraphical error or ink spill on the page would require him to start over. Pages were discussed in advance and areas for illuminations set aside before Baldwin could begin. Once he completed a page, it was handed over to one of the many illuminators and colourists under the supervision of Purves. Looking at his work today one is struck by the absolute perfection of it — as if the names were machine set.

The extraordinary, meticulous and consistent hand of Bill Baldwin can be seen in this two-page spread. Upon consideration, Baldwin would have had to start at the alphabetical beginning of each year of the war and continue faultlessly until the end. He would most certainly have taken his time, making sure the order, units and spelling were correct. His work looks as if it was set by a machine. No wonder this took him five years to complete. In the middle, the Remembrance Book Marker with sword emblazoned, a gift in 1949 from the British Empire Service League, holds the pages flat.

Symbolic at every level. The First World War Book of Remembrance rests in a glass-topped sarcophagus on a stone altar in the centre of the Memorial Chamber. The altar stands on a floor made from stone taken from Canadian battlefields of the First World War — Ypres, the Somme, Vimy, Verdun and others. The chamber’s floor itself lies near the base of the Peace Tower, which is the symbolic centre of Canada. Surrounding the central altar stand seven more altars made also of stone and bronze. On these altars rest the books of remembrance commemorating the war dead of the Second World War, the Merchant Marine, the Korean war, the Boer War, the fallen of Newfoundland before it entered Confederation, the war of 1812 and those who have died in the service of Canada but not in a declared war. These books carry the names of more than 120,000 men and women, more than half of which were inscribed by Bill Baldwin.

I can’t help but wonder about what Baldwin thought as he transcribed each name, rank and unit — 66,655 times in all. Sitting in the humidified office near Rideau Falls, surrounded by the quiet industry of his fellow artists, did he wonder who these men and women were? Where they lived? Their families? There futures? What was he thinking when he inscribed the names of each of the 27 Baldwins or the two William Baldwins he found in the list? Did he wonder if he had the mettle to do what these men did before their deaths? By the end of his five years of painstaking work, he, more than most non-combatants, understood the staggering cost of a total war.

When he finally completed his Sisyphean-like task in 1937, his contract was complete and he left the team, though he was brought back for some additional pages (perhaps redos that had been damaged) while he was in uniform and about to go overseas with the RCAF. There were still five more years of work remaining for Purves and his illuminators and binders. Sadly, James Purves died three years later and two years before the final Book of Remembrance was unveiled on its stone altar in front of Prime Minister William Lyon McKenzie King.

Baldwin then got a job at CKCO, a radio station in Ottawa where he was a jack-of-all-trades, taking the mike to deliver the news each evening. He gained a lot of technical experience at the station — announcer, transmitter, studio operations, sound recording, and publicity work. After a year, he left the radio station for a steady government job as a commercial artist with the art division of the National Park Bureau. Here he did hand-tinting of photographs, “lantern slides”, illustrations, exhibits, pen lettering as well as book and pamphlet cover design. Work not unlike I do every day. It was likely a dream job for Baldwin, but it was short lived. When war broke out, it wasn’t long before cutbacks in non-war departments were put in place and his position was cancelled in 1940. Out of work and with the war now starting to ramp up, Bill Baldwin had nothing holding him back from enlisting in the Royal Canadian Air Force.

He signed up in June of 1940 with the Battle of Britain just starting to rage in the skies over the east and southeast of Great Britain. Every young Canadian man who wanted to join the RCAF in the summer of 1940 was inspired by the stories of Douglas Bader’s 242 “Canadian” Squadron and the RCAF’s 1 Squadron. The vast majority of aircrew-able men put down Pilot as their first choice for their air force career. But not Bill Baldwin. He wrote down that he wanted to be an Air Gunner first and then later added Observer as his choices. Perhaps he understood that, at 31 years old, he had little chance of being selected for pilot training at that early stage of the war. In his attestation interview on May 29, 1940, his interviewing officer stated that he was “Very much above average in all respects”. As it turned out Baldwin was far from above average when it came to his military education. [Thanks here to Hugh Halliday for his meticulous research into Baldwin’s service file].

Baldwin’s perfect penmanship was not limited to the Book of Remembrance. In filling out his attestation papers on the day he joined the RCAF, he took extraordinary care. Most of these forms that I have seen (and I have seen several thousand) are hastily filled out and often with barely decipherable handwriting, but Baldwin took almost as much care in filling this out as he did with the Book of Remembrance.

The results of his coursework at Initial Training School in Toronto left much to be desired. He finished 102nd in a class of 126 students. However, course evaluators saw his potential, kindly assessing him as “Good observer material. No doubt he will do well.” They must have seen something beyond his failure to succeed at book learning.

After Manning Depot and Initial Training School, Baldwin was sent to the RCAF’s No. 5 Air Observer School at London, Ontario, starting on October 14 and finishing up January 4, 1941. During this period he logged about 42 hours as a navigator on Anson training aircraft. His marks continued in the vein of his ITS output — finishing up at or around the median for most of his subjects, one of his instructors noting that he was a “hard worker. Slow to grasp things. Failed to pass examination in Maps and Charts, but successfully passed the supplemental.” In Ground School, he finished a miserable 40th in a class of 43. Still, he was assessed overall as “Average”, suitable for commission but not good enough to instruct others. The chief navigation instructor assessed him positively as had his ITS instructors stating that Baldwin was "Very neat in his work. Will make a good officer with a little more experience. Pleasing personality. Well liked by his class mates and the instructors.”

A great photo of Bill Baldwin in full flying kit adjusting his RAF Mk IX bubble sextant. Baldwin proved to be an excellent combat navigator, much respected by his crew, helping them survive a full operational tour, but he was miserable at astro navigation while in training. Hugh Halliday, aviation historian states: “In Ground School he had truly terrible marks (28 percent in Astronomical Navigation, Plotting and 25 percent in Astronomical Navigation, Written). He failed the course and ranked 82nd in a class of 82. Photo via the Canadian Virtual War Memorial

From Air Observer school he took a five week course at No. 1 Bombing and Gunnery School at Jarvis, Ontario on the shores of Lake Erie. Here, he would also produce disappointing results, graduating dead last in his class of 40 gunnery and bombing students. The school commander Group Captain George Watt once again kindly summed him up as "Energetic and confident. Tried hard but did not stand out in any way." This time, he was deemed unsuitable for a commission.

Mid-February of 1941 found him back in London’s No. 5 AOS for an advanced navigation course. His result was the worst yet, once again coming dead last in a class of 82 students. The Chief Instructor stated that "This NCO seemed to have difficulty with arithmetical figures but otherwise is a good student.", which leads one to believe that he suffered from some form of dyscalculia, a specific and persistent difficulty in understanding numbers which can lead to a diverse range of difficulties with mathematics. I’m no psychologist, but how could a man who would later be awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross and be noted as a “navigator of exceptional ability” under combat stresses, fail so miserably and yet have everyone all the way up to the school CO rooting for him? Dyscalculia, however is associated with ADHD and it’s hard to believe he suffered from that particular disorder if he managed the meticulous perfection of the inscription of the 66,655 names of the Book of Remembrance over five years.

It was well that he earned his wings earlier in his first AOS course at London, for there is no way he would have graduated with the result of his Advanced Navigation Course. In June, he left for Great Britain, but not by ship as most servicemen and women travelled. According to one report in the Ottawa Citizen, Baldwin went by B-17 Flying Fortress. The only B-17s to serve with the RCAF were with 168 Heavy Transport Squadron. Used as mail planes, they were not acquired until late 1943 and ‘44. However, the Royal Air Force operated 20 Flying Fortresses (called Fortress I in the RAF) and they were delivered in the late spring and early summer of 1941. It appears that Baldwin got permission to fly across the Atlantic in one of the delivery flights, but I doubt that he was the only navigator aboard. It’s hard to believe that a newbie navigator, especially one of Baldwin’s recent scholastic record, would be given the responsibility of navigating a brand new B-17 from Newfoundland to Greenland to Iceland to Scotland. But the experience was no doubt inspiring and educational for the neophyte nav. After a short operational training course on the Vickers Wellington at No. 12 OTU, RAF Chipping Warden, he was posted to 405 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force. Incredibly, in spite of his poor showing in school, he would successfully navigate his Wellington and Halifax bomber crews to their targets and back home safely 32 times at night and under attack. Whatever coping mechanism Baldwin used to overcome his deficiencies, it would serve him and his crew mates admirably.

On Squadron with 405

The first mention of Bill Baldwin in the 405 Squadron Operations Record Books was on September 5, 1941 when he was posted in to the squadron at RAF Pocklington in Yorkshire. It would be five weeks before he went on his first operation — to bomb harbour and railway targets in Ostend, Belgium. He flew in Wellington LQ-M (W5496) under the command of Sergeant pilot McLennan. On that same bombing operation was then-Flight Lieutenant Johnny Fauquier, who would become a Bomber Command legend and be awarded no less than three Distinguished Service Orders and one Distinguished Flying Cross, making him to highest decorated Canadian airman of the war.

On the 16th of October, he took the same crew to Duisburg, to bomb industrial sites along the Rhine River [Duisburg lies at the confluence of the Rhine and Ruhr]. On the way back they encountered “a stranger with no navigation lights” and “no engagement followed”. Whether it was a night fighter unaware of their presence or a friendly aircraft, it was never determined. On the 22nd they pushed deeper still into Germany, this time to Mannheim, where they had difficulties picking up the target. By this time it was becoming clear that his crew was being formalized — the pilot being Sgt McLennan and the rest being Sergeants McKinley, Paige and Forester and that “their” aircraft was Vickers Wellington LQ-P.

A typical Rolls Royce Merlin-powered Vickers Wellington Mk II, the type operated by 405 Squadron when Baldwin first arrived at RAF Pocklington. Photo Imperial War Museum

The 24th of October found the crew of LQ-P on a mission to heavily defended Frankfurt with “unusually accurate” flak encountered. At the end of the month they were heading much farther north to Hamburg with high explosives and incendiaries, but McLennan, Baldwin and crew were forced to turn for home when they realized that their intercom was not working. Without a way to communicate with other members of the crew, there would be no way to conduct a bombing mission. They were back on the ground short of an hour after takeoff.

Things were quiet for the next week, until, at the operation briefing on November 7th, they were informed they were “going all the way” to Berlin, the most heavily defended city in Germany. This turned out to be the crew’s longest bombing operation to date with LQ-P tucking its wheels in the wells at 2319 on the 7th and returning 7.5 hours later. The weather was abysmal with 10/10 cloud and few breaks. Crews were bombing based on dead reckoning and estimates, but McLennan bombed through the cloud on the exact estimated time of arrival (ETA). For his troubles, his aircraft was hit by heavy flak and the front turret, tailplane and starboard engine were holed. Only five aircraft made it to Berlin with four opting for their alternate targets at Kiel and Wilhelmshaven. Those four crews had a much shorter operation due to not pressing to the target. According to the Operations Record book (ORB), the “weather made the sortie practically abortive.” One Wellington, piloted by a former RCMP constable from Saskatchewan named Alec Hassan failed to return. The crew was lost.

It’s quite an achievement for a navigator who graduated in the bottom half of his class and utterly failed his advanced navigation course to navigate his bomber at night in bad weather with no sight of the ground most of the way to Berlin, a distance of about 1,000 kilometres or more depending on their course changes, and successfully release his payload over the target at the ETA, then after being damaged, bring them home safely. Something had clearly changed in Baldwin’s approach to navigation.

Two days later, with Wellington “P for Peter” (LQ-P) being repaired, the crew climbed into another squadron Wellington, LQ-Q, “Q for Queenie” for another sortie against the docks of Hamburg on the Elbe River. Of the squadron, only three aircraft including Baldwin’s “Q for Queenie” managed to attack the proposed target. They were back at Pocklington 5 1/2 hours after launch. Unfortunately, the rest of the month of November, 1942 is missing from the ORB, so I cannot determine Baldwin’s bombing sorties for that period, but the squadron was active according to the diary.

The next occasion when Baldwin’s name appears on the ORB is on the night of December 22nd and all of his former crew mates are gone except for Sergeant Paige. Looking at the ORBs it does not appear that the others were posted out of the squadron in either November or December, so perhaps they were on a training course off base. On this particular night he flew with Wing Commander Fenwick-Wilson, the squadron’s commander and native of British Columbia. Flying in Wellington LQ-U, they attempted an attack on the docks at Wilhelmshaven but due to heavy undercast (10/10) made an attack on the seaplane base at Borkum Island off the Baltic coast of Germany. Weather and training kept the squadron out of the action for the rest of the month.

A photo of the RAF Pocklington operations room with 405 Squadron airmen poring over maps before the night’s operation. At the back, third from the left is Wing Commander Fenwick-Wilson, Commanding Officer of 405 Squadron. The date on the board is August 12, 1941, three weeks before Baldwin’s arrival on squadron.

On the night of January 7/8 1942, he was back with his old crew aboard “Q for Queenie” on a trip to Saint-Nazaire at the mouth of the Loire River on the Bay of Biscay. It doesn’t specify in the ORB if they were targeting the dock in general or the German submarine pens specifically, but their load of a single 1,000 and four 500 lb bombs with Small Bomb Containers of incendiaries could do little damage to the concrete pens. The bomber was equipped with a camera which later showed moderate results. Afterwards, they flew to Vannes farther up the coast, then inland to Ploërmel and then back to Saint-Nazaire to drop “nickels”, RAF slang for psy-ops leaflets. They were home in Pocklington by midnight, the whole sortie taking 6.5 hours.

In January, following the attack on Saint-Nazaire, Baldwin and Fauquier, two hometown heroes, appeared together in the Ottawa Citizen just three days after the raid.

The ORB shows little or no operational flying for several days following the Saint-Nazaire raid due to bad weather. There was some local flying for training purposes, but on the night of January 17/18 Baldwin was back in the action on a raid led by Wing Commander Fenwick-Wilson to the river port city of Bremen at the end of the shipping channel of the Weser. The weather en route was poor, but four squadron aircraft managed to drop on Bremen with Johnny Fauqiuer dropping a 4,000 lb high explosive bomb known as a “cookie” and witnessing “devastating results”. McLennan and Baldwin and crew in LQ-P were forced to return due to lowering oil pressure and landed 3 hours after they took off. The squadron suffered the loss of Wellington LQ-L piloted by Squadron Leader Walter Keddy, DFC. The radio operator aboard Keddy’s Wellington had reported they were returning to base with engine trouble just an hour after takeoff and out over the North Sea. Twenty minutes later a Coastal Observer Corps post reported a flaming aircraft, believed to be a Wellington, down in the sea 20 miles off Skipsea, Yorkshire. One of the greatest fears of Bomber command crews was to ditch in the North Sea, especially in January. The chances of survival were slim, especially if forced to swim. After 17 hours, two of the crew, Flight Lieutenant Scrivens the navigator and Sergeant Turnbull, the Wireless Operator were found in a dinghy. Both were suffering from frostbite, exposure and other injuries.

At the end of January on a raid on Hanover, they were again forced to return, this time due to hydraulic failure in the front turret. Bad weather prevented operations for the first half of February, and the McLennan crew missed out on all of February’s raids — to Le Havre, Mannheim, Kiel and one attack on “battleships” at sea.

In March, Baldwin, who now was a commissioned Pilot Officer, appears to have joined another crew captained by Pilot Officer Keith Thiele. Perhaps McLennan’s tour had timed out as he is not seen again in the ORB. Thiele of the Royal New Zealand Air Force, like the Canadian Fauquier, was a widely respected and highly decorated pilot of the Second World War. Having completed a full 32-op tour in Bomber Command with 405 Squadron, he took a demotion to Flight Lieutenant in order to return to flying status, this time completing another 24 ops. He was then granted six months leave, but chose to return to operational flying after just two months, this time completing more than 150 sorties on Spitfires, Typhoons and Tempests. The crew were very proud of their commander. Their American Wireless Operator, Flight Sergeant R J Campbell was quoted in an American magazine that Thiele was “the best little bomber pilot in the whole RAF and everyone of us looks up to him… … I would not like to go out in any kite now that did not have Keith at the controls.” For Baldwin, this would prove prophetic indeed.

Squadron Leader Keith Thiele, DSO, DFC and Two Bars, the uber-competent aircraft commander of Baldwin’s first tour crew.

Baldwin’s new crew took part in raids on the Renault factory in Paris, the docks at Saint-Nazaire, industrial sites in Essen (two raids). On the 28th of the month he was Navigator with his “B” Flight commander Squadron Leader John McCormack of Toronto, in LQ-L for a raid on Lübeck, south of Kiel on the Baltic Sea. On this raid, Baldwin’s aircraft was attacked by a Messerschmitt Bf 109 on the port quarter, but managed to escape with violent evasive action. According to the ORB, the raid (which of course involved far more aircraft than those of 405) left the city in flames. Sadly, McCormack was killed in a flying accident a week later on April 4th, along with Flight Lieutenant William Fetherston of Arnprior. They were together in a Miles Magister training aircraft which may have been the station hack. They were performing aerobatics close to their Pocklington home. Eye witnesses stated that they failed to complete a slow roll and dived while inverted into the ground and were killed instantly. The squadron ORB expressed how the whole squadron felt about the loss of McCormack, stating that he:

“was the very able leader of “B” Flight and was not only popular with the men under his command but with all those who enjoyed his acquaintance. He was one of the first to be posted to this unit since its formation in June 1941, and had since completed 25 operational sorties. Among the targets which were effectively attacked were: BERLIN (three times), TURIN, ITALY, PARIS, LUBECK, several trips to BREST, and numerous other important military objectives in GERMANY and occupied territory. His daring and courage displayed in leading his men have always proved an inspiration under his command.

Born in Toronto, Canada on September 19, 1920 he was the highest ranking officer in the group considering his age. His untimely death in these critical days was a severe shock to the Squadron and his friends. His experience and unfailing devotion to duty will be sadly missed.

Such was the shock at the loss of their leader that no mention was made of Fetherston in the ORB other than to say he was with McCormack in the Magister. Fetherston, a former teller with the Royal Bank of Canada, left behind in Toronto his recent bride Helen and an infant daughter he had never seen. He had previously been a Private with the Lanark and Renfrew Scottish Regiment

The Miles Magister in which McCormack and Fetherston were killed was likely the station hack used for liaison, refresher flying and for a little bit of fun during down time. Photo via silverhawkauthor.com

Left: Squadron Leader Jack McCormack and Flight Lieutenant Bill Fetherston smile as they walk from their 405 Squadron Wellington in this publicity shot. Bill Baldwin would replace Fetherston on McCormack’s last operation. McCormack (top Centre) and Fetherston (right) were close friends and were buried together in a station-wide military funeral at RAF Pocklington. Bottom right: A wagon carries McCormack’s coffin followed by a large procession and military band. Interesting to note that the coffin is draped in a Union Jack and not the Canadian Red Ensign or the RCAF Ensign.

Flight Lieutenant Thiele (promoted to Squadron Leader after the accident) took over command of McCormack’s “B” Flight and Baldwin rejoined his crew on LQ-P for a raid on Cologne (Köln) on April 5th. Three days later on April 8, the Squadron buried McCormack and Fetherston with full military honours. Photos were taken of the funeral procession to send to the families in Toronto. Immediately following the funeral, the Squadron was briefed for the night’s raid on Cologne. Baldwin and Thiele ran into heavy flak over the target and the squadron ORB states that “Sisters proved ineffective on flak”. As far as I can tell, “Sisters” was the RAF’s code name for coloured recognition flare cartridges fired from their Wellington in the hopes that they would match the Luftwaffe colours of the day and thus call off the attack. Further raids continued to Dortmund and Hamburg. The raid on Hamburg would be the squadron’s last on the Vickers Wellington.

Throughout May, there was no operational flying. The beloved Johnny Fauquier of Ottawa became the squadron’s new CO and oversaw the conversion of the crews to the much bigger and more capable Handley-Page Halifax II heavy bomber.

During their Halifax conversion schedule, the station had a visit from 1426 Enemy Aircraft Flight of the RAF on May 14. Pilots of 1426 EAF took their aircraft on the road to fighter and bomber bases across England, escorted by Allied fighters in case they were mistaken for the enemy. The 405 Squadron ORB states that “They proved to be a very interesting sight and novelty for our airmen.” Here, in a similar scenario, a pilot of the “Rafwaffe” chats with and answers questions from pilots and air crew at an American base later in the war.

By the 25th of May, the squadron had at least 16 fully-qualified Halifax crews ready for operations. In the last night of the month, it was time for their first Halifax operation. And what a first trip it was. Code named Operation MILLENNIUM, it was the first of the three terrifying 1,000 plane raids put together by Bomber Command. Squadron Leader Johnny Fauquier led the 16 other Haifaxes of 405 and joined a staggering 1,030 other medium and heavy bombers of Bomber Command — Halifaxes, Lancasters, Manchesters, Sterlings, Wellingtons and outdated Hampdens, Whitleys and even Blenheims (everything that could be mustered, including 375 operational training aircraft and crews) — on an attack on the city of Cologne. The concept of the thousand-bomber raid was hoped to inspire the home front with the rising hitting power of the RAF and strike terror and force a morale breakdown among the enemy citizenry.

That night was a night of many firsts for Bomber Command— 405 Squadron’s first Halifax operation, the first Thousand-Bomber Raid and the first use of the Bomber Stream concept. The bomber stream was a saturation attack, 4-6 miles wide, up to 50-60 miles long and thousands of feet high, designed to overwhelm one particular sector of the complex and layered German defensive system known as the Kammhuber Line.

Baldwin, Squadron Leader Thiele and the crew of LQ-M (W7704) took off just before midnight on the 30th, and worked their way into the bomber stream heading towards Cologne. En route, Thiele and his gunners twice spotted a strange formation of lights on two occasions, once at 4,000 feet at 0140 hrs and then again an hour later at 12,000 feet as the approached the target. The lights were in the form of a large “V” pointing west at the apex of which was white rotating beacon at each trailing end a bright flashing light. No one else reported seeing these lights. The ORB gave no indication whether these lights were on the ground or airborne. Were these “Foo Fighters” or some kind of Luftwaffe target diversion? As they approached Cologne, fires started by bombers at the head of the stream gave them an easy target to find, but when they opened their bomb bay doors and hit the electric bomb release it failed to work and their entire bomb load hung up. Efforts to shake them off failed and they closed up and headed for home with a belly full of fused ordnance — three 1,000 lb HE bombs, 12 Small Bomb Containers packed with incendiaries—landing without incident at Pocklington at sunrise.

The folks back home in Ottawa must have been pretty proud of Baldwin when he appeared in the June 15th, 1942 edition of LIFE magazine in a feature story about Bomber Command and the Thousand Bomber mass raid on May 30th on the city of Cologne. Baldwin (left) is seen here having a post-op cup of tea with his American Wireless Operator Flight Sergeant R. J. Campbell. Photo via LIFE

They were back in a Thousand-Bomber stream the very next night, this time to Essen and again, they were the only crew to report strange lights in the sky. The ORB states that at 2:30 a.m. they saw “lights in the form of V with three lights in each arm all white except centre one of the arm which was red with rotating white beacon at apex and flashing white light at open end of the all white arm.” They also saw a “white flashing light on port side irregularly and a steady white light on sea.” There were only three so-called Thousand-Bomber Raids carried out against German targets in the war. Thiele, Baldwin and their crew were on all of them, the third and last of which took place at the end of June when Bremen was attacked. On June 6, they went to Emden, on the 8th to Essen and then the last Thousand-Bomber Raid on the 25th.

As the summer wore on, operations continued with 405 Squadron joining raids every few days. Baldwin and the crew returned to Bremen on July 2 in LQ-R, which had become “their” Halifax since the Thousand-Bomber raid the week before and then to Wilhelmshaven on the 8th. Finally, after the Wilhelmshaven raid it appears he and his crew got a break for they didn’t fly again until the very beginning of August. During that time, Baldwin was promoted two ranks to Flight Lieutenant, skipping over Flying Officer.

On the Night of July 31/August 1st, 11 of 405’s Halifaxes launched against Düsseldorf, the heart of the industrial valley of the Rhine. Baldwin’s crew took off in LQ-R at 30 minutes past midnight and were over the target at 2:57 AM. Thiele reported that they could make out the serpentine folds of the Rhine and that features of the city were blotted out by the smoke and that “the city was a mass of flame with reddish flame rolling up.”

Handley Page Halifax Mk II LQ-R (WW7710) “Ruhr Valley Express” in which Thiele, Baldwin and crew attacked Düsseldorf and Bremen. The nose art featured a locomotive pulling a line of rail cars. After each operation, the ground crew added another car to the train. Photo: Imperial War Museum

A great shot of Thiele and Baldwin’s Halifax LQ-R in flight. All aircraft wore the LQ 405 Squadron code along with a letter (R) denoting the specific aircraft. Generally, but not slavishly, letters A to M were reserved for “A” Flight while N to Z were for ‘B” Flight. Baldwin was assigned to “B” Flight and most of the Wellingtons and Halifaxes he flew in followed that rule LQ-R, LQ-Q, LQ-P.

It was a costly night, with two of the squadron’s Halifaxes failing to return with no contact received after takeoff. Of the crew of LQ-T, captained by Sergeant Donald E. West, there were two who didn’t make it — Flight Sergeant Laurent Nadeau and Sergeant I. Watters (RAF). Four others became POWs and one evaded. Halifax LQ-S, piloted by RAF Sergeant Jack Hunter was shot down near Vorst, Belgium with all crew killed including Jack Irish, a young radio operator from Baldwin’s Ottawa neighbourhood.

By this time, with the number of operations climbing closer to a full tour, Bill Baldwin’s nerves must have been at a breaking point. At four o’clock in the afternoon of August 2nd, the day after the devastating Düsseldorf raid, Thiele (with Baldwin) and Fauquier took off together for a daylight two-ship 405 Squadron showing on a raid to Hamburg. They each carried seven 1,000 lb bombs in the bays. Both aircraft turned back for a strange reason — the lack of cloud cover over the target. The ORB actually states “Both Captains returned to base bringing their bombs back since there was no possibility of cloud cover over the target.” While it seems strange that they would return to base when they could see the target clearly, it was standard operating procedure in Bomber Command that on daylight raids, unescorted bombers had to abort the raid if they could not find at least 7/10ths cloud cover. Without cloud cover to hide in they would be sitting ducks for German fighter aircraft. This would be Fauquier’s final op with 405 Squadron. The next day it was announced that he had been awarded a DFC. The ORB states:

“Although recognition of the valuable contributions made by the Wing Commander was long expected, yet the announcement came as a pleasant surprise and members of the Squadron were quick to extend hearty congratulations to their leader. The award is more than justified in view of the continued daring with which he inspired those under his command in the many undaunted attacks he lead on countless occasions over enemy territory.”

August was a busy month with the squadron undergoing a change of address and command. Baldwin and his crew participated in only one more raid — to Duisburg on the 6th. This was also Thiele’s and Baldwin’s last operation. The very next day, 405 Squadron picked up stakes and moved to RAF Topcliffe. Topcliffe was a much bigger base which accommodated two other RCAF squadrons — 419 Moose Squadron and 424 Tiger Squadron. The 405 Squadron ORB reported on the move, which was a common and often annoying experience for a settled squadron:

“Movement of the Unit: The main body of personnel and equipment of 405 Squadron left Pocklington by road convoy and by air transport and proceeded to RAF Station Topcliffe. All aircrew and part of the servicing crews of the respective aircraft left by air while the remainder of the personnel were taken by lorry and bus. The convoy left RAF Station Pocklington shortly before 11.00 A.M. and after an uneventful trip reached RAF Station Topcliffe after 2 p.m.

On arrival the various sections were met by members of the advance party and conducted to the barrack block allotted to them. Although there were many minor adjustments to be made before everyone was finally settled each and every individual expressed keen satisfaction and displayed every delight after viewing their new surroundings. It became evident that morale and the consequent well-being of the men and the war effort would be considerably improved under the ideal conditions afforded the Squadron in their new home. It was obvious that few regretted the Squadron’s move and all looked forward to an indefinite stay here.”

As happy as they were with their new home, they were sad to see their beloved leader go. Wing Commander Johnny Fauquier left the squadron on the day they moved for a posting at RCAF headquarters in Ottawa. The squadron ORB entry displays the love they had for this man:

“The announcement was accepted with regret on the Squadron’s part, but at the same time congratulations were in order since the posting will pave the way for ever greater success. Johnny leaves an envious record behind him as he bids everyone a reluctant farewell; a record that not only will be an inspiration to those who will succeed him but one which will ever exist in the spirit of the squadron itself. His daring exploits and undaunted leadership more than justified his recent awards of the D.F.C. and friends and relatives of the Ottawa Valley boy may proudly acclaim his amazing rise to fame. Although the Squadron will greatly miss this capable leader who had been with the Squadron since its formation, every good wish is extended to the Wingco in everything that is expected of him in the future.”

Newly-promoted Wing Commander Gordon Fraser, former “A” Flight commander took over command of the squadron and prepared 405 for further ops from Topcliffe. Squadron leader Thiele, Baldwin’s pilot and “B” Flight leader was also leaving the squadron, being posted to No. 10 Operational Training Unit at RAF Abingdon in Oxfordshire. He was also awarded a DFC. After briefing the new commander, he left on the 14th with the ORB lamenting his loss:

“Another valuable and popular member of this Squadron is lost to us in S/Ldr. K. F. Thiele, DFC, who has left to join his new unit No. 10 OTU. Since his arrival with the Squadron on October 15th 1941, this captain has stamped himself as an exceptional pilot and his ability was not long in being recognized since he was given our “B” Flight to command shortly afterwards. The Squadron will sadly miss his natural ability and the vast amount of experience he had amassed in his many successful operations, but it is realized that a man with his envious record of service will be in a position to pass on his valuable knowledge to those who, it is hoped, will imitate it.”

A full-page advertisement in the Ottawa Citizen on the day of the unveiling of the Book of Remembrance uses an illustration of the altar where Baldwin’s work lies and heavy moral suasion to pressure citizens of Ottawa to buy more war bonds. Image via The Ottawa Citizen

With the departure of Thiele, most of his crew had timed out on their operational tours including Baldwin who had successfully navigated his aircraft and mates deep into the heart of Germany on 32 occasions. It’s hard to believe that a a man who had been “Slow to grasp things”, who “seemed to have difficulty with arithmetical figures” and who “failed to pass examination in Maps and Charts” had done so well under extreme duress to successfully complete those 32 sorties. Compare those remarks to the citation accompanying his award of a Distinguished Flying Cross in June (gazetted in October and presented to him December 8 at Buckingham Palace by His Majesty the King):

“Pilot Officer Baldwin is a navigator of exceptional ability which, combined with his courage and initiative, has contributed materially to the success of the operations in which he has participated. His unfailing cheerfulness and optimism, in spite of all hazards, has proved a source of inspiration.”

By September, most of the other crews that Squadron Leader Thiele and Flight Lieutenant Baldwin had flown with had been shot down or timed out and left the unit. The squadron ORB reads like another squadron altogether after September, 1942.

For the next few months, we lose track of Baldwin as he awaited orders for his next posting. I don’t have Baldwin’s personnel records to verify where he went after he left 405, but it appears that he traded a 6-month leave in Ottawa for the promise to return to operations afterward.

On November 11, 1942, while he awaited orders and passage to Canada, the Book of Remembrance, a project to which he had dedicated five years of his life, was finally unveiled in Parliament. After James Purves died in 1940, the project was taken over by his very able assistant Alan Brookman Beddoe, a combat veteran and German prisoner of war in the First World War, who took the Book to its completion (Beddoe would spend the next thirty years of his life as the chief artist of the remaining books, dying in 1975). Among Beddoe’s many accomplishments were the design of ship’s badges for more than 180 Royal Canadian Navy vessels in the Second World War, the design of the Royal Canadian Legion badge, designs for many municipal Coats of Arms including those of Ottawa and Kingston, The Royal Arms of Canada and involvement in the modern Canadian flag.

At the official unveiling of the First World War Book of Remembrance, Prime Minister William Lyon McKenzie King (with magnifying glass) closely inspects Baldwin’s work and the beautiful illuminations created by artists like the young Sylvia Bury (right). At left is Colonel Archer F. Duguid, head of the Historical Section of the Canadian Army, Dr. Gustave Lanctot, respected Canadian historian and long-time Dominion Archivist, Colonel J. W. Flanagan, the Prime Minister, Colonel Henry C. Osborne, Secretary of the War Graves Commission and Ms. Bury. Photo: Canadian Virtual War Memorial

The Ottawa Journal devoted almost a full page on the dedication of the work of Purves, Beddoe, Baldwin and the members of the team of artists who created the Book of Remembrance. Both the Ottawa Journal and Citizen were drawn to the physical charms of one of the artists, Sylvia Bury, who worked on the project. She was featured in several newspaper articles in both papers about the book, though was only one of several woman artists who worked on the book. One of the others, Grace Melvin, is credited for bringing modern calligraphy designs to Canada.

A montage of images about the Book of Remembrance was featured in the Ottawa Citizen on Remembrance Day, 1942. Again, the lovely Sylvia Bury is featured while other, more key women artists are not. I suspect that this is because Bury was physically attractive. At right bottom of the montage is a photo of a page of Baldwin’s exquisite hand highly illuminated by members of the team.

SIDEBAR: Not germane to Baldwin’s story, I still found the details of one of his fellow artists interesting. Miss Sylvia Rita Bury of Ottawa (Upper Left) was photographed numerous times (lower left) in stories about the creation and unveiling of the Book of Remembrance — likelysimply because she was attractive. There were at least five other woman artists from Ottawa (calligraphers and colourists) employed in the production of the book — Edna Bond, Patricia Macoun, Evelyn Lambert, Grace Melvin, Florence Meagher—but only Bury was ever photographed. In September, 1942, a month before the unveiling of the Book, she was in Halifax, Nova Scotia under contract to Universal Film Studios as the stand-in double for movie star Ella Raines (top centre) in the film Corvette K-225, a theatrical propaganda piece released the following year. She was an amateur dancer and musical theatre actor (bottom centre), appearing with fellow book artist Edna Bond in several Ottawa Little Theatre revues and plays. Inspired by her work on the movie and the book, she joined the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (Wrens) and served on the West Coast.

While Baldwin could not be in attendance for the unveiling of the Book, his contribution was well covered by both of Ottawa’s daily newspapers. There was particular interest in the irony that Baldwin was overseas risking his life as did the 66,655 men whose names he had so carefully and respectfully inscribed in the pages of the massive tome. The Ottawa Citizen reported:

“The 68-pound volume containing 606 beautifully hand-illustrated pages on which an Air Force hero of the present conflict, Flt. Lt. W. H. Baldwin, DFC has penned the names of more than 66,655 Canadians who gave their lives in the war of 1914-1918, will be placed in a casket on a carved stone pedestal in the centre of the vaulted memorial chamber….

… Flt. Lt. Baldwin, an amateur penmanship expert and cartoonist of Ottawa, son of Mr. and Mrs. C. J. Baldwin, then just out of his teens, was given some vellum and told to submit samples. These were satisfactory and he took on the task as a full time job. He had never taken professional training for penmanship other than that gained at common school.

After some time spent in compiling the list and putting the names in proper order he started the actual lettering in 1934. It took him five years at full time and there were additional pages which he completed in 1941 after he had entered the RCAF. Baldwin went to England in June 1941 and last September [sic] he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross after more than a year’s fighting in the air over the British Isles and Europe.”

A week after the unveiling on November 11, a larger-than-normal photo of Baldwin with his DFC ribbon and crush cap appeared on the front page of the Ottawa Citizen to announce his promotion to the rank of Squadron Leader. The short piece notes that:

“… in June, 1941, he flew to England in a Flying Fortress and has been on active service there since. He rose through all the ranks to his present high station by his outstanding abilities as a flyer and a bomber, having taken part in many devastating raids over Germany and occupied Europe. For his part in one of these he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Before the war, Squadron Leader Baldwin worked as an illuminator [sic] on Canada’s Book of Remembrance, which was recently dedicated in the Peace Tower. He is a graduate of Glebe Collegiate.”

This photo of Bill Baldwin with his Distinguished Flying Cross ribbon and his Observer’s wings appeared large on the front page of the Ottawa Citizen. As a seasoned navigator, his hat has a suitable casual crush. Baldwin does not seem to have been diminished by the stresses of 32 terror-filled operations over enemy territory. Photo via the Canadian Virtual War Memorial

Home for a spell

Bill Baldwin, having flown from Great Britain to Montreal, arrived home by train in Ottawa on Sunday, December 27, 1942, a year and a half after going overseas. His arrival was greatly anticipated by his family and friends and was reported in both newspapers. On the 28th, the Journal broke the good news of his homecoming and quoted a rather humble Baldwin who refused to line shoot and would not put himself at the centre of the story :

‘Shakey Dos‘ Over Ruhr Valley Won Sqdn. Ldr. Baldwin D.F.C.

Gallant Ottawa Flyer Gives His Whole Plane Crew Credit for His D.F.C.

A couple of “shakey dos” over the Ruhr Valley is the way Squadron Leader W. H. (Bill) Baldwin explained his Distinguished Flying Cross upon his arrival back in Ottawa Sunday afternoon.

The 32-year old flyer is a son of Mr. and Mrs. C. J. Baldwin, 182 Fifth Avenue. He telephoned his family in the morning from Montreal to expect him sometime during the day and a whole delegation watched the clock from 12 noon until the train pulled in at one. Looking extremely fit, Squadron Leader Baldwin caused one, member of his family to exclaim: “Who said he was thin!”

Overseas since June, 1941, Squadron Leader Baldwin was loathe to discuss that D.F.C. “which really isn’t mine but belongs to the whole crew”.

For the last 18 months he has been navigating Wellingtons and Halifaxes on operational flights over enemy territory. Flying with bomber squadron 405, the “Target for Tonight” for his bomber took him on 32 raids—two more than the average Air Force “tour”—mostly to the Ruhr though he was over Berlin and took part in the 1000-bomber raid on Cologne.

Johnny Fauquier was the wing commander and commanding officer of his squadron until Fauquier came home on leave during the Summer. Asked for details of his adventures, Squadron Leader Baldwin passed them all as routine and remarked, “I couldn’t tell you anything you haven’t already heard a dozen times”.

Lauds His Crew

He placed the greatest importance on his crew and like every other airman who has returned home thinks his is the best in the business. His skipper was squadron leader Keith Thiele, a New Zealand pilot, while an American [Campbell - Ed], a Frenchman and an Englishman made up the rest of the crew—quite an example of co-operation by the United Nations.

Squadron Leader Baldwin described the English people as “doing nicely”. He spent a good many of his leaves not in London or Edinburgh, but at the Buckinghamshire home of Sir Norman Birkett, distinguished member of the English bar and well known in Ottawa. Sir Norman and Lady Birkett have a penchant for Canadians and have almost adopted Squadron 403 [sic], a fact which the boys really appreciate. …

… He was unable to say what he would be doing when his present leave expires. “Needless to say, I’m glad to be home”.

As for his mother, Mrs. Baldwin could not have looked happier if Santa Claus had left a whole Christmas tree in her stocking.

Sir Norman Birkett, First Baron Birkett, MP was to become one of the two British judges at the Nuremburg Trials of Nazi war criminals.

Little is known about Baldwin’s leave in Ottawa but there is some hint in the research of Canadian military historian Hugh Halliday who wrote that “RCAF wished to retain him in a Training Command function "to proceed on a tour of all Initial Training Schools and Air Observer Schools to lecture aircrew on the latest Bomber Command practice in Navigation." However, permission to take leave from Bomber Command had been on condition of his returning to Bomber Command“. Six months leave was a long time and it is likely that he was not out of uniform the whole time.

One thing I know for sure, though it is not reported on in the papers, is that Baldwin must have gone to Parliament Hill to view the completed Canadian Book of Remembrance on the Memorial Chamber altar. The sacrifice made by those 66,655 men and women was already fully understood by Baldwin, but seeing them through the lens of an air force officer who had experienced the true terrors and brotherhood of combat must certainly have driven the emotions even deeper.

It’ll be Fun! Fun! Fun! A full page advertisement in the Ottawa Journal mentioned that Bishop and Baldwin (highlighted in yellow) would be on hand to hand out prizes.

Little snippets of his personal life appeared in in the papers over the months, revealing some of his activities—the activities of a hometown hero and local celebrity. On January 5th, 1943, a week after his arrival back home, the Journal mentioned him in a story about skiers waiting for the train to Camp Fortune ski hill north of Ottawa and being disappointed when the train was cancelled. Baldwin was athletic by nature and enjoyed skiing and tennis before the war. Prior to the war, Baldwin associated with local skiing legends Eugene and Bruce Heggtveit, and Olympian Bud Clark all of whom were now in the RCAF. Standing on skis at the top of Camp Fortune was a long, long way from the night sky over Berlin. Another pilot, Tommy Du Broy was also mentioned in the piece. Du Broy would not survive the war either.

On January 8th, Baldwin and Wing Commander Ken Boomer, DFC were guests of honour at a Rotary Club luncheon. Ken Boomer, a well-known Ottawa fighter pilot of the RCAF fought both the Japanese in Alaska and the Germans in Europe. He also did not survive the war, being killed on operations in October, 1944. The Citizen sports section reported on January 19 that he was skiing with a Flight Lieutenant Dick Travers and Johnny Fauquier’s wife at Camp Fortune.

On January 29th, Baldwin was given the honour of “facing the puck” [now called “dropping the puck”] at a hockey game at the Ottawa Auditorium on O’Connor Street. The game was between the RCAF Flyers, holders of the Allan Cup and an all-star squad hand-picked from the Ottawa Senior City Hockey League. Unfortunately, Baldwin was “unable to attend, but the crowd stood up and cheered when his name was mentioned”. Before the start of the game, a memorial service was held for former pupils of Ottawa High Schools who had lost their lives while serving with the armed forces.

On May 20, it was reported he was to be on hand at a big dance held at the Auditorium and sponsored by the Air Force Officers’ Wives Association. He was to present the prizes to the winners of the “spot dances” along with none other than Air Marshall “Billy” Bishop, VC, DSO, MC, DFC, LLD.. That he was held in similar esteem as one of Canada’s greatest war heroes of the First World War speaks volumes of his reputation in his home town. The event sold out with 1,500 tickets purchased and it was reported that Baldwin was a judge and presenter for the jitterbug contest. I feel that Baldwin must have thought as other war heroes have thought on their fund-raising or bond selling tours that they would much rather be back with their comrades in England. He was indeed a sport for consenting.

His leave was coming to a close and he now faced the prospect of operational flying once again. When he left is not known at this stage, but by July 3, the papers reported that he was already back overseas. In another article that same day, entitled Canadian Flyers on Every Front, there was a mention of him that shows the high esteem in which he was held in the Ottawa area: “… don’t forget these other Ottawa flyers: Bill Baldwin, Johnny Fauquier, Larry Robillard, Carl Fumerton, Mervyn Fleming…”. I don’t expect everyone to know all these names, but every one of them became larger-than-life legends of the Royal Canadian Air Force… except Baldwin.

Baldwin’s service and recent adulation inspired his youngest brother to join up. On July 21, a story appeared in the Citizen stating that his younger brother James Hubert had enlisted in the RCAF, “determined to be as useful to his country as his older brother”. The piece also stated that another brother, Warrant Officer Clayton Baldwin Jr, was also serving with the RCAF.

Returning to the Maelstrom

On June 26, Baldwin boarded another aircraft for a three day flight back to England. Baldwin rejoined his former squadron, now at RAF Gransden Lodge, Bedfordshire. There was only one man from his previous tour who he recognized, and that was his commander. Wing Commander Johnny Fauquier had left Ottawa in April and returned to command his old squadron again. Baldwin knew him well from previous operations and his home leave when he socialized with Fauquier and his wife.

Wing Commander Fauquier was on his second of three full tours, and as commander he certainly had the pick of the litter when it came to his crew. Of the seven men in his crew, three had Distinguished Flying Crosses and one a Distinguished Flying Medal. These men no doubt were on a second tour as well as there were, in addition to Fauquier’s rank, two Squadron Leaders, one Flying Officer, two Pilot Officers and only one non-commissioned officer. His navigator, Squadron Leader Peter G. Powell, who had flown with Fauquier on his previous tour, became Chief Navigator for Trans Canada Airlines (now Air Canada) immediately after the war. He is a member of Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame as is Fauquier himself. This was an extraordinarily experienced and gifted crew.

Wing Commander Johnny Fauquier, DSO and Two Bars, DFC standing next to a 22,000 lb Grand Slam “Earthquake Bomb”. Fauquier commanded 617 Squadron (the Dam Busters) from December 1944 to April 1945.

While Fauquier had the commanding officer’s prerogative to choose the best of the best, the most experienced of aircrew at each position, his friend Bill Baldwin did not. After refresher flying, he joined a crew captained by Pilot Officer Frank Harman, a former delivery man for “Bob Hanes’ Meat Market” of St. Catharine’s, Ontario. Like Baldwin, he was older than the rest of his crew at 26 years. The crew’s Bomb Aimer was 23-year old Flying Officer Phillip Magson of Quesnel, British Columbia. Magson was on his first tour, but he had experience unique among his crew. Flying with 408 Squadron in June, his Halifax was attacked by a night fighter near Auchen, Germany. The attack left them without hydraulic power for the bomb bays and landing gear. They limped home and all abandoned the aircraft by parachute over the North York Moors. The two gunners in Baldwin’s new crew were 20-year old Flight Sergeant Allen Menzies of Toronto, with nine successful ops behind him and 19-year old Flight Sergeant James Miller, the rear gunner. The crew included two Royal Air Force members as well, Pilot Officer Leslie King, DFM, the crew’s Flight Engineer and Wireless Operator Sergeant Sidney Cugley.

Like Baldwin, King was experienced and on his second tour. He had joined the RAF in January of 1936 and trained originally as an “aircraft apprentice” which I believe to be a rigger or mechanic of some sort. He was Mentioned in Despatches in September of 1941 during the time of the Battle of Britain. In February, 1942, he went to an Air Gunnery School and then was posted to 77 Squadron for four months before being posted to 405 Squadron and the crew of Sergeant B. C. Dennison. At that time, 405 Squadron was loaned to the RAF’s Coastal Command to operate anti-submarine and anti-shipping patrols. He finished his first tour, was awarded a Distinguished Flying Medal and promoted to Pilot Officer when he opted for a second tour with 405 Squadron.

Frank Harman was an avid motorcyclist, and on his attestation papers, he stated that he had “a motorcycle and some experience racing and working on them. Have been riding for seven years and like travelling fast.”. “This boy is tops” wrote his boss, Bob Hanes in a letter of recommendation and support when he enlisted,. “He came to me as a very small boy to deliver and collect money. He was smart and quick to learn and well behaved. His money was always correct to the cent. I cannot give this young man too much praise. His integrity, honesty and character are absolutely beyond reproach.” Photo via Canadian Virtual War Memorial

In April of 1943, 405 Squadron had changed its role in the RAF’s structure. It was selected to become a Pathfinder squadron. The Pathfinders were target-marking squadrons in Bomber Command during the Second World War. They located and marked targets with flares, which the following main bomber force could then aim at, increasing the accuracy of their bombing. Pathfinders were on the target first and on the accuracy of their flare drops depended the accuracy of the whole raid. Pathfinder crews considered themselves the best of the best, and rightly so. That is why the revered Wing Commander Johnny Fauquier was sent back to command his old squadron. In particular, Navigators and Bomb Aimers of each crew were of critical importance and so were selected for their experience and success. For Baldwin, the poorly-performing navigation student, to be selected for this role was a vindication of his true abilities.

First Sortie, Last Sortie

The weather on the night of the 23rd of August, 1943 was fine over England and Western Europe. There was broken cloud at 2,000 feet and visibility, which started out as moderate, became excellent over Germany. The winds were light and blowing from the southwest. In the briefing room, there was a deep resigned sigh as “Berlin” was announced as the target for the night. A raid on Berlin was always tough — farther than the Ruhr and Baltic targets, it was more heavily defended than any city in Germany and the trips were both exhausting and dangerous. There were 15 Halifax and Lancaster crews detailed from 405 Squadron. The ORB states that both types from 405 Squadron were involved in the raid, so this was the period of transition to the Lancaster. The raid was to be massive — 727 Halifaxes, Lancasters, Stirlings and Mosquitos would comprise the bomber stream. 405 Squadron would go in first to mark the targets. Every man in the briefing room understood that many would die this night, and that likely someone from 405 would be among them.

Baldwin, Harman and crew climbed aboard Halifax LQ-G (HR918) in the RAF Gransden Lodge dispersal at about 7:45 in the evening. The sun was low on the horizon. The light streaming into the cockpit and mid-upper turret was golden and the temperatures warm and agreeable. They had taken off in the dark on most raids they had been on in the past, but now as Pathfinders, they needed to leave well ahead of the main bomber stream. The extra light meant they could see inside the fuselage without a torch. Harman squeezed himself forward to the cockpit and then climbed awkwardly up to his high mounted seat, followed by Les King who slid into his narrow compartment behind Harman. King stood aside to let Baldwin, young Magson and Sid Cugley squeeze past him down a step to their positions beneath the pilot. Later, just before takeoff, he would fold down a “dickie” seat where he would spend much of the flight adjusting the throttles and propeller speed settings and monitoring the temperatures and pressures of the four Merlin engines on an instrument bank behind the pilot. His secondary job was as a back-up pilot in the event that Harman was incapacitated. He had rudimentary flying training and was expected to bring the aircraft home if needed.

As the three crew members positioned in the lower nose compartments squeezed down the stair, there could be heard the hollow scrape of boots on aluminum, the clink of parachute harnesses, the heavy breathing and low curses of stressed men accompanied by the smell of gasoline, leather, sweat and aftershave. Menzies crawled forward to the nose where he would also operate the forward gun when he wasn’t lying prone over his bombsight on the run in to the target. Immediately behind him, Baldwin sat 90 degrees facing his tiny plotting table and navigation instruments and aft of him, directly below the pilot’s position, wireless operator Cugley squeezed himself into a tiny metal alcove where he would spend the seven hours of the operation. Though they would fly over Germany in total darkness, there was now, with the sun setting, beautiful golden light streaming in though small windows at each position as well as through the nose glazing. James Miller, the teenaged rear gunner, turned right at the crew hatch and crawled to the rear beneath the tracks of belted ammunition that fed his four Browning machine guns in the electrically powered Bolton-Paul rear turret. Squeezing in, he slid the turret doors behind him and settled into utter isolation. Lastly, mid-upper gunner Allan Menzies bent over, slid sideways through the hatch, closed it and turned left to the rotated drum of his dorsal turret. Looking up at the fading evening light he climbed and twisted until he was settled behind his four Browning machine guns.

After Harman and King got all four engines running smoothly, all needles in the right places in their dials, there was a radio and intercom check and everyone settled in for the next seven or more hours of claustrophobia, boredom, discomfort, fear, and possibly terror. Harman gave a thumbs up to the aircraftman below his window and then saw him dash under the wing and drag out the big wooden chock with the letter “G” painted on it and move clear of the propellers on the port side. With King now at his side, they reached for the four tall throttle levers to Harman’s right and walked them up and forward until the engines thundered and “G for George” overcame her inertia and began to roll.

They trundled out onto the dispersal track and joined the 14 other Halifaxes and Lancasters as they headed towards the threshold of the runway in the last of the evening light. Only seven of the Halifaxes were loaded with general purpose bombs (ten 500-pounders each) and the rest were loaded with various combinations of target indicators, star shells, High Capacity 4,000 lb. bombs known as “Cookies” and 500 lb. Medium Capacity bombs. They were second in line behind Pilot Officer Bernard Francis McSorley, a commercial artist and window dresser from New York, in LQ-R, and ahead of Warrant Officer Hector “Snuffy” Smith in LQ-V. Two of these crews would not return — Smith’s and Harman’s. The Smith crew was set upon by night fighters and damaged in a running fight with Messerschmitt Bf 109 night fighters. Running low on fuel, they flew north to the Baltic and ditched in shallow water three miles off the Swedish coast. Smith and his crew were interned in Sweden and eventually made it back to England in March, 1944. McSorley survived the night, but not the war.

At 8:15 PM, Harman, with King, pushed the throttles fully forward, released the brake paddle on his steering yoke and began the long sluggish roll down Runway 22 to take-off speed — lifting off with the disappearing sun off his right shoulder and his long shadow to his left. Harman, following the disappearing silhouette of McSorley’s Halifax, made a slow climbing turn to come around to the east, to Berlin and the threats that lay there. Everybody aboard knew the risks ahead, yet they went about their tasks with grim hearts and taut faces wanting only to keep each other alive. The squadron would hear nothing of their fate for many weeks.

Ernst Heuer’s account of what happened that night states that he saw the flash and heard the explosion of a bomber crashing at 3 a.m. in the morning. Heuer’s remembrances also seem to indicate (if I can sort through the terrible and partial translation) that the Halifax jettisoned their bombs when first attacked. This means they were still on their way to Berlin. I find it hard to believe that that would be the case. The 405 Squadron ORB clearly indicates that all of the surviving bombers were safely back between 3:30 a.m. and 4.a.m. McSorley, for instance, who took off just before Harman, completed the op and was home by 3:40. Flight Lieutenant Keith LeFroy in LQ-C, who took off an hour after Harman, was safely on the ground at Gransden Lodge at 4 a.m. At 3 a.m. local time, it would have been 3 a.m. in Gransden Lodge as England was on Double Daylight Savings Time (DDST) during the war (and Berlin was on DST), this making up the one-hour time zone difference. Harman would have been in the air for nearly seven hours when he crashed. All the other crews took off from Gransden Lodge, set-up for the run-in to Berlin, dropped their loads and were back home no later than seven hours later. That means it took only 3.5 hours to get there. Taking into account any possible headwind it’s hard to understand how he would be over Saturelle/Haldensleben nearly seven hours after take-off and still have 130 kilometres to go before reaching Berlin. Their load was most certainly expended on Berlin but perhaps they were returning with a hung bomb and were finally able to jettison the ordnance through agressive defensive manoeuvring — causing it to finally fall free. Or perhaps the bomb came from another aircraft.

Evidence of the gunfight over Satuelle between Baldwin’s Halifax and the German nigh fighter still exists to this day in the form of this large bomb crater in a wooded area. The bomb likely came from HR918. Photo: Peter Milner

From Heuer’s account of that night and the following day, it appears that Harman, Baldwin and crew were attacked by a Messerschmitt Bf 109 night fighter. In the attack there was some sort of gunfight between Miller in the rear turret and the pilot of German aircraft. Miller was killed in the attack and the Halifax set on fire. Another account from the War Graves unit after the war mentioned that the Halifax was circling overhead. At some point, Harman realized that the Halifax was doomed and ordered everyone to abandon the aircraft. Of course, in the dark, on fire and descending rapidly, this was brutally hard to do. None of the men in the nose and turrets wore parachutes as there was no room to move about the tight confines of the Halifax crew stations with them on. While their parachutes were all handy to them, putting them on in the pitch dark, in an aircraft on fire and hurtling out of control would have been nearly impossible. Baldwin’s parachute was immediately behind him under a folding bench. The only escape hatch for the forward crew positions (Pilot, Navigator, Radio Operator, Flight Engineer and Bomb Aimer) was directly below his feet, which might explain why he was the only one to exit the aircraft and why there were multiple bodies found near the hatch — those of Harman, Magson, King and Cugley. It’s likely that the other body which was discovered near the wreck largely intact was that of Menzies, the mid-upper gunner. His position would have been in the less damaged rear of the aircraft. He also would have attempted to exit the aircraft through the crew entry hatch, which was just aft of his position. Perhaps he was at the hatch, and knowing he was too low to jump, decided to see where the falling aircraft would take him. He was not in the aircraft when found which leads credence to the idea that he was at the open hatch and thrown clear. Baldwin’s body was found a few days later hanging from a tree a distance from the wreck site, but that does not explain how he died.

There were five Canadians and two Brits aboard Halifax LQ-G when it was shot down. The Canadians, in addition to Baldwin, were Pilot Flying Officer Frank Harman of St. Catharines, Ontario; 19-year old Rear Gunner F/Sgt. James Miller from Mactier, Ontario; Mid-upper Gunner F/Sgt. Allan Menzies of Toronto and Flying Officer Philip Magson of Vancouver, British Columbia.

The two British crew members were from the Royal Air Force —Pilot Officer Leslie Ronald French King, DFM, Flight Engineer and Wireless Operator Sergeant Sidney Cugley. Cugley is sporting a winged “S” Signaler brevet which according to a couple of aviation history forums I visited was not issued until February of 1944, 6 months or more after this photo was taken.

Feldwebel Franz Laubenheimer (right) with two other Luftwaffe comrades: Unteroffizier Heinz Emanuel (Left) and Hauptmann Ludwig Hölzer, later in the war. Laubenheimer was shot down and killed in March of 1944. Photo via Kracker Luftwaffe Archive