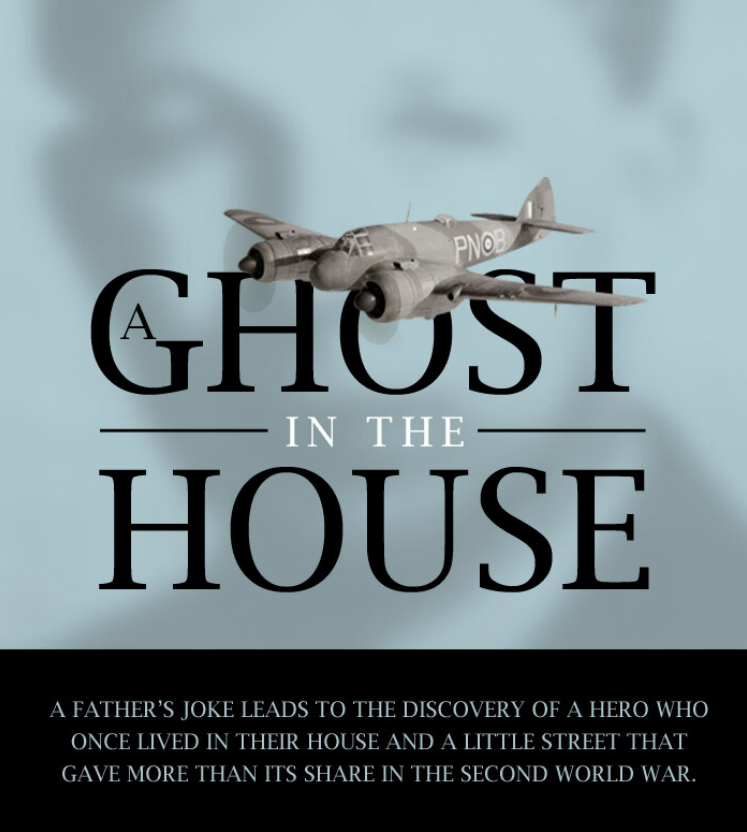

Sentinel—The Ron Moyes Story

17-year old Aircraftman Second Class Ronald “Shorty” Moyes shortly after his enlistment in September, 1943. Photo: Moyes Family Collection

Introduction by Dave O’Malley

During the Second World War, the Bomber Command rear gunner had what is arguably the most dangerous and ultimately deadliest job of any combatant in the war. Of the 125,000 Bomber Command aircrew who fought in the war, 55,573 were killed— a horrifying 45% of all operational aircrew. To put this into perspective, the United States Army Air Force's 8th Air Force – the Mighty Eighth – had 350,000 aircrew members of which 26,000 were killed in combat – a 7.45% death rate, which was a terrible price to pay, but one that pales in comparison to that of Bomber Command. One would think that these Bomber Command deaths might be relatively spread out across all crew positions in the aircraft — pilot, navigator, radio operator, engineer, bomb aimer, mid-upper gunner and rear gunner. There was however an astonishing asymmetry to the dying in a bomber. Of the 55,573 deaths in Royal Air Force bombers, approximately 22,000 were rear gunners, accounting for 40% of the deaths yet only 14% of the crew positions. Over the course of the war, Fighter Command lost 3,690 pilots killed in action and in accidents. More than 6 times more rear gunners lost their lives over the same period!

A couple of things come to mind to explain this asymmetry. Firstly, Bomber Command, for the most part, operated at night and night fighters almost always chose to attack a bomber from the 6-o’clock position low. Much of the time, the first the crew knew of the presence of a night fighter was when its pilot opened fire, hosing the bomber and its exposed rear gunner with tracer fire. In such an attack, the bomber might escape by “corkscrewing” away, but upon returning to base find its rear gunner either dead in his turret or gone altogether. According to science writer Tom Whipple in The Battle of the Beams, if a radar-directed night fighter made contact with a bomber, they were successful in shooting it down 60% of the time.

Secondly, it was extremely difficult to get out of a rear turret in the event the pilot ordered the aircraft abandoned. In heavy leather and fleece clothing he either had to rotate his turret to align with the entry door and then crawl backwards into the fuselage then find and attach his parachute with the longest distance to the escape hatch (the main door in the case of the Lancaster) or depending on the aircraft, he had to rotate his turret hard left or right and drop out of the opening into the slipstream (only if he had is parachute on). If his hydraulics were shot out he could not easily rotate to align the openings with either option. All of this desperate struggle was under the extreme g-forces of a bomber spinning down to the ground.

Young Commonwealth rear gunners may not have known these terrifying postwar statistics, but they were fully aware that they had the most dangerous job in the bomber and that they would take the first hit. For them, there was not the comfort of proximity which the pilot, navigator, bomb aimer, engineer and radio operator all enjoyed up front — within reach, within sight and within contact. Even the mid-upper gunner could drop down in the fuselage and come forward. The rear gunner was 50 feet or more aft, bucking in the slipstream, cut off from the warmth and camaraderie of the front by his claustrophobic turret doors, stabilizer and wing spars, darkened fuselage and was linked only by a fragile intercom wire and infrequent check-ins from the pilot. He was alone— with his thoughts and fears. Over enemy territory and even over England, he strained for hours to catch sight of a nightfighter creeping in the blackness and gloom. And when he did, a fight to the death might follow.

Here is the story of one such hero— Warrant Officer Second Class Ron “Shorty” Moyes, a rear gunner with 429 Squadron on Halifaxes and then with 405 Squadron Pathfinders on the Lancaster. He defied the 16 % odds (likely less than 10% for tail gunners) that he would survive a full tour (30 ops) and live to tell us about the experience.

Ron Moyes died on January 4, 2025 in Ottawa in his 99th year. In his 80s, he authored a short memoir of his war experiences that appeared as an 8-part series in Observair—the newsletter of the Ottawa Chapter of the Canadian Aviation Historical Society (CAHS). This testament, written with clarity and humility, is a lasting tribute the bond that was created when a Bomber Command crew was forged. Most crews parted company at the end of hostilities and for the most part never saw each other again. The Walkley Crew (crews were always named for the pilot /commander) remained in contact well into their 70s — proof of the love these six Canadian men shared in times of mortal danger. With the kind permission of the CAHS, we present it here in its entirety.

On a Wing and a Prayer

by Flight Sergeant Ron Moyes

I was sworn into the RCAF on 16 September 1943. I remember that my parents had to sign a form of consent as I was only 17 years old. On 17 September 1943, I arrived at No. 3 Manning Depot at Edmonton. We were soon made aware that a corporal had the power of a general. We learned discipline the hard way, but we persevered.

My older brother had been Overseas as an aircraft engine mechanic in Bomber Command since 1941. He told me that the fastest way to get Overseas was to train as an air gunner. I found out only later that air gunners had the highest casualty rate. But thank goodness that was changing. After a month of learning housekeeping, marching, and getting needles for every disease under the sun, we were transferred to No. 9 Pre-Aircrew Education Detachment at McGill University in Montreal. The RCAF had taken over one residence and some classrooms. We took math, science, and especially Morse code and aircraft recognition. The Morse code just about drove us all nuts. With everybody learning the alphabet in Morse, all you heard was Di, Da, Di, Da. We also learned to read Morse by Aldis light which, from experience on Ops later, was more important to us. There were about 80 of us and we had to pass this course before going on to the main Air Gunners Course.

Bing Crosby and many other top celebrities performed for Allied servicemen and women at New York’s Stage Door Canteen. Photo: nationalww2museum.org

While at McGill, three of us got a 96-hour pass for Thanksgiving weekend. We decided to go to New York City. We bought our train tickets, after which we each had about $12.00 left. In New York City, we arrived at Grand Central Station and reported to the "R.T.O." Office. (I think that stood for Regional Travel Office.) They directed us to the U.S.O. at the famous Stage Door Canteen, where they welcomed us and gave us tickets for accommodation at a small hotel. We also received tickets to see Glen Miller’s orchestra, as well as tickets to the Radio City Music Hall, the Empire State building, and a movie of our choice. We had a great time and saw everything, including our first TV, which was about 12 inches, in Grand Central Station; a huge crowd was watching. When we returned to Montreal, we had change in our pockets – you sure can’t do that today!

Rail travel for servicemen during wartime is worth mentioning. A ticket from Vancouver to Halifax cost $15.00, plus 75¢ for breakfast, $1.00 for lunch, and $1.25 for dinner. These were full course meals. A berth for a night cost $1.00. This seems pretty cheap today, but when you consider that our pay as airmen was then about $35.00 a month, from which we would sign over $15.00 to our parents, leaving us with $10.00 every 2 weeks for such things as soap, toothpaste, smokes, etc. We got by O.K.

From pre-aircrew school, we were transferred to No. 9 Bombing and Gunnery School at Mont Joli, Quebec, right on the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Well, what a shock it was to us westerners; the snow was up to the cross bars of the telephone poles, and cold – something like minus 25° to minus 30° with the wind blowing off the Gulf!

Here we went into more training of enemy and friendly aircraft recognition, plus Morse code at faster speeds; also stripping Browning .303 machine guns, learning all the parts’ names and what they did. We also went up for flights in Fairey Battle aircraft, in which we fired the guns over the Gulf. If the guns froze up – as they usually did – we’d just pitch the remaining ammo out. It would land either in the water or on the ice; we didn't care, as long as we got rid of it.

Graduation came and we were promoted to Sergeant and given the Air Gunner’s single-winged badge to sew on. Our pay went up; to around $3.00 a day. We were also given 30 days leave to go home, which was nice.

Ron Moyes (top) attacks the climbing net on the assault course at Aircrew Physical Training School in Valleyfield, southeast of Montreal. Photo: Moyes Family Collection

After our leave, we reported to Valleyfield, Quebec, on 12 April 1944, where we attended the Aircrew Physical Training School. This was a very good course. They trained us hard physically, but fed us well. Going over the assault course daily, we were soon in very good shape. Our next transfer, on 23 April 1944, was to Lachine, Quebec; where we waited to go Overseas. On 2 May 1944, we left Montreal by rail to Halifax to catch the Empress of Scotland, which departed on 3 May.

There were about 80 air gunners and as we went up the gang plank we were directed to the top deck where they had canvas lean-to’s in which were bunks; three-high. There were about 30 bunks, then a canvas partition and another 30 bunks, another partition, another 30 bunks. Our bunks were two feet wide, with a round pillow and two blankets. The first night, we just about froze; there was no heat and the Atlantic is cold and miserable that time of year. We took everything we could out of our kit bags to use as covers. For nine days we never had our clothes off; it was awful.

While aboard, we were assigned to a gun watch, manning the 40 mm anti-aircraft guns which were positioned around the top deck. We were given a ten-minute run-down on how to operate them, and that was it. Each group of 30 men was given a watch, which coincided with the regular sailors’ watch of duty. Our ship was on its own; no escort and more than 3,000 troops on board.

Canadian Pacific’s Empress of Scotland painted battleship grey during her period as an Allied Atlantic troopship. She was originally built a as a luxury passenger liner on the trans-Pacific routes and launched as Empress of Japan, but in 1942, following the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor, Singapore, and Hong Kong, she was rechristened Empress of Scotland. During 1943 and 1944, Empress of Scotland operated a shuttle of twelve transatlantic round trips, bringing troops across from New York and other North American ports in preparation for the invasion of Europe. Despite intensive U-boat activity in the North Atlantic, she came out unscathed. Photo: Imperial War Museum

We disembarked at Liverpool on 12 May 1944, and were sent by train to the Personnel Reception Centre at Innsworth, Gloucester. Previously, all RCAF personnel had gone to Bournemouth on the south coast, but with D-Day pending, personnel were moved inland. When I went into my assigned barracks the first thing I saw was my sister’s picture. I wondered who had that and why? Well, it turned out to be Fred Jones, a neighbour and an air gunner. Fred and I both ended up on 405 Squadron later the next year.

From Innsworth, we were sent to various Operational Training Units (OTU). About 20 of us were sent to No. 82 OTU at Ossington, Nottinghamshire. This was a big move, as this is where we got crewed up with the men we’d be flying with as a crew for the rest of the war.

Operational Training

At No. 82 Operational Training Unit (OTU), Ossington, Nottinghamshire, the various aircrew members were assembled according to their trade; i.e., Pilots, Navigators, Bomb Aimers, Wireless Air Gunners, and Air Gunners. All the crew members, except the pilots, wore the single wing: ‘N’ for Navigator; ‘B’ for Bomb Aimer; ‘E’ for Engineer; ‘WAG’ for Wireless Air Gunner; and ‘AG’ for Air Gunner.

Coming from different holding units or training stations in Great Britain, we all (i.e., our future crew) arrived at this station on approximately the same day. Then one particular day, we were all assembled by the flight section. The pilots were told to go pick themselves a crew from those assembled. So, our future pilot, Don Walkey, went over and asked our future navigator, Hugh Ferguson, if he’d like to join his crew. Fergy said “O.K.” Don then said, “O.K., you go pick the rest of the crew.” So it was Fergy who picked us all out.

Flying Officer Don Walkey from Pincher Creek, Alberta, had joined the RCAF at age 18 in 1941, and took pilot training. Upon graduation, he was commissioned and then assigned a job as a flying instructor in Canada. He was finally able to get out of that in 1944.

Pilot Officer Hugh “Fergy” Ferguson from Winnipeg, Manitoba, joined the RCAF early in 1943 and trained as a navigator. Upon graduating, he was commissioned, and posted Overseas. Prior to joining the RCAF, he had mined abandoned mines all over Manitoba.

Pilot Officer Stuart “Stu” Farmer from Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, joined the RCAF at age 22 in 1943. He trained as a bomb aimer, graduated with a commission and, just prior to going overseas, he married.

Sergeant Alvin “Al” Kuhl grew up in Tara, Ontario, and was the son of a farmer. Al joined up at age 22 in 1943. Al trained as an air gunner and sailed overseas in the Spring of 1944.

Flight Sergeant Jake “Red” Redinger joined the RCAF in 1941 at the age of 25. He was from Bashaw, Alberta. Upon graduating from wireless school, he was posted to Eastern Air Command in Nova Scotia, where he flew coastal patrols in Hudson aircraft. After many operations, the crew was picked to fly aircraft Overseas with Ferry Command. Red was one of two wireless operators with the crew; only one was required in Ferry Command. To determine who remained, the two flipped a coin; Red lost the flip. Later on, all that crew were killed while towing gliders.

Finally, I was the Rear Gunner, Sergeant Ron “Shorty” Moyes, from Coquitlam, British Columbia. I had quit high school to join up in 1943 at the age of seventeen.

The Walkley Crew. Left to right: Sergeant Ron “Shorty” Moyes, Rear Gunner; Pilot Officer Hugh Ferguson, Navigator; Flying Officer Don Walkley, Pilot; Pilot Officer Stuart Farmer, Bomb Aimer; Sergeant Alvin Kuhl, Mid-Upper Gunner; Flight Sergeant Jake “Red” Redinger, Wireless Operator. Ranks at time of photo. Photo: Moyes Family Collection

Ossington had been constructed in 1941, and all its buildings were Nissen-type buildings – which was the main building type used in England during the war – constructed of corrugated steel, half round in shape, with a concrete slab floor. There was one hangar for aircraft under repair. The NCO’s barracks – also Nissen huts – were about ¾ of a mile from the centre of the base. The huts were heated by one pot bellied coal burning stove. The washrooms were in a separate building with wash basins, showers and toilets; the only trouble was there was no heat or hot water.

As the Wellington aircraft and its equipment were new to all of us, the first few days were spent learning the equipment. We started flying by doing simple take-offs and landings as a crew; then progressed to short navigation flights, followed by practice bombing flights, and finally practice gunnery flights over the North Sea.

On one such navigation training flight over the North Sea at night, I saw a light blinking behind us. I told Don and he asked if it was sending a Morse code letter by Aldis? I then looked again and said, "Yes, the letter so-and-so.” He immediately told Red to fire off the ‘colours of the day.’ Each aircraft had a Very pistol capable of firing 1½" x 4" flare cartridges. The cartridges came with two stars in them; these could be a red and a green star, or two reds, or a red and a yellow, a green and yellow, or whatever. So Red fired off the colour for the day and the blinking went away. Don told us later that this was likely a ‘friendly’ night fighter, but if we hadn’t answered correctly, he would have fired at us – live and learn.

Another night we were scheduled to do a night bombing training trip. Don and another pilot, Ray Charlton, had a bet on to see who would be first to take off that night. Well, we got out to our respective aircraft, each quite a ways apart, meaning that we’d have to taxi the aircraft from our dispersal positions to the runway. Both aircraft were heading towards the same point before coming onto the runway. I don’t remember if it was Stu or Fergy, but one of them yelled over the intercom to hold it. Don lost the bet.

On another night bombing training flight, a Wellington aircraft exploded directly ahead of us; no survivors and we never heard what caused it.

We finished our OTU training on Wellington aircraft on 4 September 1944. The next day we were on our way to the 6 Group Aircrew School at Dalton for a two-week course on escape and evasion from the enemy. There they taught us how to hide our parachutes or how to cut them up for warmth if we were forced to bail out over enemy territory. We carried pens, pipes, etc., all with small compasses in them. We learned how to ration the goodies in our escape kits, and how to approach farm houses, etc. It was a very interesting course; thankfully, one we never needed.

On 19 September 1944, we arrived at No. 1659 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) at Topcliffe, Yorkshire, just north of the city of York. Here we converted from twin-engine Wellingtons to four-engine Halifax Mk. IIIs. This involved quite a change for the gunners too as the turrets in the Wellington had been hydraulically-operated, whereas the Halifax had Bolton Paul electrically-operated turrets; very different. In addition, we were assigned a Flight Engineer, Sergeant Doug Durkin from Meaford, Ontario, who sat beside the pilot and looked after the fuel supply, etc. One of the first of the new trained-in-Canada flight engineers, he had little experience when he came to us with just 13 hours of total flying time.

Topcliffe had been started as an RAF station just before the war, so its hangars and buildings were all brick. But they lacked accommodation for NCO aircrew, so they put us up in a big estate home about 2½ miles from camp. All the NCO members of our crew were in one room. Each room had a small fireplace for heat, fuelled by coke, a by-product of coal. We were allowed one pail of coke per week; actually just enough for one night. We broke up wooden shutters and any other wood we could find for heat.

We did a lot of training in October, at the end of which we were transferred to No. 429 Squadron at RCAF Station Leeming. We were now going on Operations.

429 Squadron – First Op

We arrived at RCAF Station Leeming on 29 October 1944. There were two RCAF squadrons of Handley Page Halifax Mk. III bombers on the station: 427 (Lion) Squadron, and our squadron, 429 (Bison) Squadron, sponsored by Lethbridge, Alberta. Leeming was a pre-war RAF station, with married quarters and permanent brick buildings, located just north of the city of York. The three officers of our crew were assigned to Officer’s Quarters, with the rest of the NCO crewmen assigned to a living room in one of the former married quarters.

On the night of 30 October 1944, our pilot, Don Walkey, went on an operational trip to Cologne as a second pilot with Flight Lieutenant (F/L) D.C. Henrickson’s crew to gain familiarization of an operation. On 1 November, he went with F/L G.W. Bennett’s crew to Oberhausen. The first week or so on the squadron, the rest of us did ground training with a few training flights to get used to the squadron routine.

On 16 November 1944, we were informed that we would be making our first operational flight as a crew and, as it turned out, it was a daylight raid. We were awakened at about 430 hours, got dressed, and went to the Sergeants’ mess for our Operational breakfast. This consisted of a fried egg, fried potatoes, toast and tea. Before and after an operation were the only times we got fresh eggs. From there, we went to the briefing room for 930 hours. This was a large room capable of holding up to 200 men. But on this raid, there were only 14 crews, about 100 men.

After being seated, we watched as the Commanding Officer dropped a sheet, exposing a map of Europe and showing a red tape going from Leeming to the German city of Jülich, just east of the Ruhr Valley; the Ruhr Valley being the most industrialized and heavily defended portion of Germany. The red tape did not go straight from base to target, but instead went straight for some distance, then turned 30 degrees or so for a distance, then back again 50 degrees. It was explained that these changes in direction helped avoid heavily defended areas, but also kept the Germans from calculating what the target was so they wouldn’t be able to concentrate all of their fighters on the target before we got there.

After the briefing, we knew what the target was, why it was selected, and what kind of weather we would encounter, plus the number of aircraft going on the mission. (Bomber Command had been given the task of bombing three German towns – Düren, Heinsberg, and Jülich – just behind the lines that the American First and Ninth Armies were about to attack. 413 Halifaxes, 78 Lancasters and 17 Mosquitos of 4, 6, and 8 Groups were to bomb Jülich.) Then most of us went away to get dressed for the operation, leaving behind the navigator and bomb aimer to plot the course.

We had been told also what height to fly along the route, the weight of bombs we would be dropping (one 2,000-lb High Capacity (HC) bomb, seven 1,000-lb Semi-Armour Piercing (SAP) bombs, and four 500-lb SAP bombs), the height to bomb from (17,000 feet), and to-the-minute when we should release the bombs. Now this was very important: if you got off course or were left behind, the fighters would pick you off. Your height and time-on-target were also important, as the bombers were stacked to fly at about 500-foot levels above one another, starting at 17,000 feet up to 21,000 feet, so it was very important for someone in the crew to watch out for any aircraft above that might happen to have their bomb bay doors open to tell the pilot to get out of the way before a load of bombs dropped on you. This happened many times when crews weren’t paying proper attention. This also meant that after getting out of the way, you would have to do a complete circuit and start another bombing run, going through all the danger of being hit by flak a second time.

“… it was very important for someone in the crew to watch out for any aircraft above that might happen to have their bomb bay doors open to tell the pilot to get out of the way” recounted Moyes. This aerial photograph, taken a couple of months before the Walkley crew arrived at Leeming, shows a Handley Page Halifax of No. 429 Squadron (LW127 'AL-F'), in flight over Mondeville, France, after losing its entire starboard tailplane to bombs dropped by another Halifax above it (very likely by the aircraft taking the photo). Three of the crew were killed, one evaded and three became POWs. Photo: Imperial War Museum

There were many ways to die for a rear gunner. Here. ground crew inspect a Lancaster which has returned from a bombing raid with its rear turret sheared clean off by a bomb falling from above. The turret and its unlucky occupant were never seen again..

After the briefing, we went to the locker room to get dressed. We had to be sure to remove everything from our pockets; like wallets, theatre stubs, letters, or anything that the Germans could use to identify our base or squadron if we had to bail out. If captured, we were to give only our rank, name and service.

It was my job to give out the crew’s escape kits; one comprising maps and European money, the other rations of high energy candies to sustain you for a few days. I was also given several bags of candies, unsweetened chocolate and six Mars bars; I never did figure out why we were issued only six Mars bars when we had seven in the crew. Maybe it was because in the days of twin engine aircraft, there were only six in the crew? Anyway, I had to keep track of who missed out on their Mars bar on each operation.

Three crew members climb aboard their Avro Lancaster. The difference between what the rear gunner (right) and the mid-upper gunner (left) wear tells you all you need to know about the brutal freezing conditions endured by Ron Moyes and all rear gunners, even on a summertime op like the one depicted. Photo: Imperial War Museum

As the rear gunner, I had the worst time getting dressed. That was because of the extreme cold in the rear turret; there was no heat and all the plastic enclosure in front had been cut out to give better visibility. The temperature when flying at 17,000 to 21,000 feet would reach between -40 to -60 degrees F. First, I would put on long wool stockings which came up over my knees, then a wool turtleneck sweater, then my battledress uniform, and then a thin electrically-heated suit with slippers and gloves. Over all that, I put on what I called my ‘teddy-bear suit’; it was about one inch thick and heavily padded. Then, I put on my flying suit, with all it’s pockets to carry my escape rations. We also carried pens or pipes which had compasses hidden in them. Next went on my Mae West inflatable life vest, and then my parachute harness. Then flying boots; these were leather and designed so that you could cut the top off making them look like an Oxford shoe. A small knife was included in the boot for cutting the top off. Also, I had my helmet, oxygen mask, goggles, and three pairs of gloves; a thin pair of chamois ones, the electrical ones, and a pair of gauntlet gloves. I should mention here that all aircrew had a whistle attached to their battledress jacket collar; the purpose of this was that if you had to ditch or parachute into the North Sea or English Channel at night, you could signal each other as to your location, to help get into the dinghy.

From the locker room, we hopped into the back of a large truck that took three or four crews out to their aircraft. Our aircraft for this trip was a brand new Handley Page Halifax Mk. III, MZ482, built by the London Aircraft Production Group, coded AL-N; “AL” were the call letters of 429 Squadron, and “N” identified our particular aircraft.

At the aircraft we stood around talking to the ground crew. No one asked what the target was; that was strictly forbidden. But the ground crew knew by the amount of fuel put in the aircraft approximately where we were going.

Before getting into the aircraft, we all had to line up to have our ‘nervous pee’ as we could be gone for 5, 6, or 7 hours, or more. Once in our positions, we stayed there until our return; the rear turret being the most cramped and lonely of all the positions. Once in, we plugged in our intercoms and waited for takeoff. After we were airborne, Don would call Al, the mid-upper gunner, and myself every half hour over the intercom to ask if we were alright, and that was it.

Take off was at 1245 hours. This was our first operation, and we were surprised when we got airborne to see other aircraft spread so far apart, and this continued until we got over Holland. Then the aircraft started coming into what I’d call a ‘stream,’ and the closer to the target, the closer the ‘stream’ came together. We could see all kinds of flak exploding up ahead of us. The first aircraft over the target were the Pathfinders and they were dropping their target indicators, which burst a few hundred feet above the target. The individual bomb aimers used these markers as the aiming point, unless told otherwise by the Master Bomber in charge of the raid.

About 5 minutes from the target, our bomb aimer, Stu, took over the direction of the aircraft, telling Don to turn slightly to the left or right until the target was lined up in the bomb sight. By this time (1548 hours), the target and markers were obscured by smoke so, on instructions from the Master Bomber, Stu bombed on the edge of the main body of the smoke. When Stu pressed the bomb release, two 1,000-lb. bombs failed to fall; their release mechanisms had frozen at altitude. Don was required to maintain course for a few more seconds so the camera could record the explosions of our bombs on the ground. Once that was done, Don turned us for home.

We found the flak really scary as it was coming up and bursting all around us. We didn’t see any aircraft get a direct hit and explode, but I’m sure a lot of them got punched with holes, and may or may not have made it back to their bases. (No aircraft were lost on the Jülich raid. Three Lancasters were lost on the Düren raid, and one Lancaster was lost on the Heinsberg raid.) We were finally able to jettison the two bombs when we had descended to 12,000 feet over the North Sea.

After an exhausting, hours-long operation over enemy territory, aircrew could finally stretch their legs and have a cup of tea or coffee (with or without rum) to help them unwind. Photo: Imperial War Museum

We landed back a base at 1835 hours. What a relief! I could finally get out of my turret and move; I had only about 8 inches to move my feet in the turret. We were taken by bus or truck back to the pre-flight building, where we removed our flying equipment. As we went in for individual crew debriefing, the padres issued us a cup of so-called ‘coffee,’ with or without a good-sized shot of navy rum. Boy that rum sure settled the nerves! After debriefing, we went back to the mess hall for bacon and eggs, then to bed. Our first trip was over.

Early Ops

Two days later, on 18 November 1944, we were back on operations with another daylight raid. This time it was to Münster, again not far from the Ruhr Valley. The routine was about the same as the raid on Jülich. The primary was attacked at 1505 hours from 18,000 feet using Gee. There was still no way to avoid all that flak that they shot up at us.

On 21 November, we were scheduled for a night operation. Al and I had been down to the flight line at around 0800 hours. We did the usual thing, like turret manipulation on training turrets. Then an hour of sitting in a theatre in the dark, practicing night vision, viewing enemy aircraft in various lighting conditions. In the afternoon, we went out to the aircraft and cleaned the guns and polished the Perspex. Following this, we went for our operational meal, then to the briefing room. There we saw that our target for the night was Castrop-Rauxel. This was an oil refinery, the first of many that we would be doing.

We took off just before 1600 hours, passing over Holland before entering Germany, and flying at around 18,000 feet. Suddenly, there was a burst of flak right behind us. I told Don and he turned off course for about 15 seconds. We were very lucky he did because there was another burst right where we would have been! We learned later that this was radar controlled flak, and it was very accurate. On several future trips we encountered this radar controlled flak and we would immediately turn off track and then back on again. But you had to move fast.

When we got to the target, the huge flames and heavy black smoke from the oil fires reached up thousands of feet. Stu released our bombs on a concentration of red and green Target Indicators (T.I.’s). Looking down at the target would cause you to loose your night vision, but I closed one eye to have a peek. It is believed that the refinery produced no more oil after this raid.

I found these night raids far worse than the daylight ones as you had more than 200 aircraft flying over the target within about 15 minutes with no lights on and stacked up at various heights. Sometimes you had to fly through clouds, and collisions often occurred. We did our bombing and got back to base okay.

The synthetic oil refinery at Castrop-Rauxel endured 35 bombing raids during the war with production finally ceased after the night of November 31, 1944. This post war photo shows the accumulated damage. Photo via. www.trolley-mission.de/

Our fourth operation, the night of 27-28 November, was to the city of Neuss. Everything went alright, but on the way home we learned that Yorkshire was fogged in and we were diverted to an USAAF base at Wendling in Norfolk. This was alright by us as their food was better than ours.

Our fifth trip, the night of 6-7 December, was to Osnabrück, a major city in Lower Saxony in the northwest part of Germany, which was a fair distance for us, taking just over 7 hours to complete. On longer trips like this one, we had to dispense with carrying two five hundred pound bombs in the underwing bomb cells. Instead, we had to install extra fuel tanks in place of these. There was lots of flak, and we saw a few aircraft that got hit. (7 Halifaxes and 1 Lancaster were lost on the raid.) When it was our time to bomb, no T.I.’s were seen, only the glow of fire under the clouds, so we decided to abandon the mission. Our two 1,000-lb bombs were jettisoned over the North Sea and we returned with the remainder of our load (1080 4-lb incendiary bombs).

Our sixth trip, the night of 17-18 December 1944, was to Duisberg, right in the centre of the Ruhr Valley. There was sure lots of flak going in and coming out. This was a raid on industrial warehouses. I believe we did alright on this target. On the way home we were once again diverted due to fog, landing at RAF Strubby in Lincolnshire.

Our next trip was a daylight raid on 26 December 1944 to St. Vith, a small village in Belgium, but important for its highway and railway junctions. The weather had at last improved and this allowed Bomber Command to intervene in the German ground offensive in the Ardennes, in what would be called “The Battle of the Bulge.” This was the first day that we were able to get airborne to assist the Americans on the ground. For a week we had been trying to help out, but had been grounded by thick fog over England and the continent. It was also during this week that we had about 8 inches of wet, heavy snow at Leeming. The C.O. had everyone on the base, regardless of rank or trade, issued with garden shovels. We were each given a big square to shovel off. Well, we worked most of the day shovelling snow; that night it snowed again. (Operations were ordered and cancelled ten times during the month because of the weather.)

Ron Moyes used his log book to map all of his crew’s operational raids from RAF Leeming with 429 Squadron and from RAF Grandson Lodge with 405 Squadron. Map via Moyes Family Collection

Anyway, we finally got away (almost 300 aircraft from all the Bomber Groups) to attack German troop positions near St. Vith. The flak was heavy and one burst hit our starboard outer engine damaging it, so we only had three engines. On the way home, we found we still had two 500 pound bombs under our port wing which we tried to drop over the English Channel, but they wouldn’t release.

Our base was again fogged in, so we were diverted to Kinloss, in the north of Scotland. With only three engines, we were the last of many aircraft to arrive. As Don brought the aircraft in, a great gust of wind from the starboard side caught our aircraft and swung it away to port as our wheels touched down. Don yelled “Hold on!” We were headed for a string of parked aircraft and buses full of crews, and remember we still had two bombs under our port wing. Don pulled back on the stick and we just skimmed over those aircraft and buses. All I can say is we were lucky we had a new aircraft. But things weren’t over yet! We were then headed straight at the control tower. Once again Don yelled “Hold on!” and he put that aircraft on its wing tip, but we made it! Three of us returned to Leeming the next day, while the rest of the crew waited until the engine had been replaced and flew home the day after.

On 28 December 1944, we did a night trip to Opladen, just east of the Ruhr Valley. This was another industrial target. We had just unloaded our bomb load and were heading for home when we were attacked by a twin-engine enemy aircraft, but were able to evade it. Soon after, Al and I both spotted a German Focke-Wulf Fw.190 fighter at about 600 yards to the rear; this was at about 0430 hours. The Fw.190 started dropping parachute flares across our flight path. This was the German trick to get us silhouetted against the light of the flares, allowing another fighter to come at us from the front. We realized what he was doing, and told Don to watch out front.

Sure enough, Don spotted a fighter coming up from in front, and he immediately put our aircraft into a corkscrew turn. The fighter shot by underneath, not getting a shot in at us. Neither Al nor I could see him as we were in the twist of the corkscrew. We kept this procedure up for at least half an hour, ducking in and out of clouds. Dawn was approaching and so was the coastline when the two German fighters finally gave up, thank goodness.

Gardening and Other Ops

We found out in the afternoon that we were scheduled for our first mining trip on 29 December 1944. Actually, it was called ‘Gardening,’ which was the code name for such operations. Our target was the fjord up at Oslo, Norway. We had been at the Section at 0800 hours, so when we found out that we were on Ops that night, we had no time to rest up; just time for our operational meal and then briefing.

On longer ops, Moyes and his crew were issued amphetamines to keep them alert and awake. The use of amphetamine was common in Bomber and Coastal Command of the RAF when men were required to remain awake and vigilant on long-duration operations. This four pill packet was part of every aircrew survival pack. Image: Imperial War Museum

There were only three 429 Squadron aircraft scheduled for this trip. We carried four 1500-pound mines; each mine had a parachute in the tail end to help break its entry into the water. The fuses could be programmed so that either 6, 8 or 10 ships would pass over before they detonated. We were briefed to keep our height below 2,000 feet so that German radar could not pick us up. Also, at briefing, we were each given two small pills to help keep us awake as we had been up since early morning.

The sky was clear and the moon was almost full. This made it easier to map read when we got to Norway. We arrived at the fjord that leads to Oslo, went up the fjord a ways, did a U-turn, and then dropped down to 800 feet. It was then that Al and I spotted a car driving along a road with its lights on. Figuring only the Germans would be doing that, we asked Don if we could open fire, and he said “O.K.” We fired and the lights soon went out. Continuing on, we ‘planted’ our four mines, one after the other, then headed for home. We had one heck of a time keeping awake, and got back to base around 2300 hours.

Two nights later we were assigned to go back to Oslo; it was New Year’s Eve 1945. We were briefed to take the same route as the previous trip. This time it was a bit different for us, as our mines had special fuses installed and we were to drop them closer to the shore in comparably shallow water. The RAF wanted the Germans to recover these mines, study the fuses, and devise a method to sweep these mines. Of course, whatever they did would be entirely wrong because of the altered fuses installed.

Once again, there was a full moon with no clouds, and after we made our U-turn up the fjord, we dropped down to 800 feet. Stu dropped the mines according to instructions. Then all hell broke loose. The sky was full of tracer rounds. Apparently, there were a couple of ships or barges loaded with guns; either 30 mm or 40 mm. Don immediately put the aircraft into a dive. Both Al and I opened fire on them, of course. We only had our .303 machine guns, but each gun fired at the rate of 1150 rounds per minute and we had 6 guns. Anyway, we didn’t take our fingers off the triggers. My guns were white hot when Stu, our Bomb Aimer, called out: "Skipper, pull up! I can’t swim.” Don pulled up and we were only 75 feet above the water. Only one round of their fire had hit us and it did little damage; I believe Red kept the fragment. Whether the Germans stopped firing because of our return gun fire or because we were too low for their guns, we never knew. It was almost midnight when we got back. By the time we were debriefed and had something to eat, it was getting on in the morning. We slept right through our New Year’s turkey dinner.

Close-up of the Boulton Paul Type 'E' tail gun-turret, mounting four .303 machine guns, on a Handley Page Halifax. Spent shells were ejected out the two rectangular ports at the back of the turret. Photo: Imperial War Museum

On the night of 2 January 1945 we were on Ops again, this time to Ludwigshafen; the aiming points were two IG Farben chemical factories. This place was very heavily defended by anti-aircraft guns. We saw several aircraft get hit. Just after we had dropped our bombs, searchlights coned us, but Don put us into a steep diving and twisting turn and we were able to get rid of them. This was another long trip, almost 8 hours, and we sure welcomed that big jigger of rum they put in our tea and coffee before we went in for our debriefing; that sure settled the nerves down.

The bad weather continued in January 1945 and all aircrew were again employed during the day clearing the runways of snow. [The 429 ORB states: “The novelty of snow shovelling has begun to wear off and the boys have developed a few sore muscles. However coffee was served after their efforts and compensated them in some small measure for their tired backs.” 10 January 1945] We were given a week’s leave in January. We were on duty for five weeks, seven days a week, then we got a week of leave.

During the rest of January 1945, we continued our flying and ground training. It was during this lull in operations that Don entered into a ‘discussion’ with the Squadron’s Engineering Officer – If you feathered all four engines in the air, could you get them restarted? Don believed you could. The Hercules engines on the Halifax required a battery cart plugged into the starboard inner engine for a ground start. The few times when we were diverted to other stations, such as USAAF stations, I would get on top of Don’s shoulders and put a hand crank into the engine to start the engine; like starting a Model-T Ford.

We were at about 10,000 feet on a training flights when Don decided he would try to prove his point that he could restart the engines in the air. But – just in case – he told us to put our parachutes on and to stand by the escape hatches. There was one problem; with all four engines feathered, Red, our Wireless Operator, would have to replace a fuse in the fuse box at his position. Don feathered No. 1, then No. 2, then 3, and finally 4. We were dropping like ‘a ton of bricks,’ as the saying goes, with Don calling for Red to replace that fuse. Unknown to them both was that Red’s intercom cord had pulled out when he had moved to the front escape hatch. At last, Fergy grabbed Red’s intercom cord to show him that it was unplugged. Red plugged in and replaced the fuse. Don was able then to restart the engines, winning his bet – point of discussion.

In the winter of 1944-45, US Army Air Corps Liberators from the 785th Bombardment Squadron are parked at RAF Leeming. The unit was based at RAF Attlebridge in Norfolk. Perhaps the unit was staging from there for a mission during the Battle of the Bulge. Photo: Ron Moyes

One day we had 24 hours off and the crew decided to go pub crawling in the city of Harrogate, south of York. The next day we were on a training trip and flew over Harrogate. One of the crew asked Don to drop down low as he wanted to show us where he had taken a girl home. We couldn’t locate the area, but Don spotted a soccer game being played on the village green and decided to buzz them. We were so low the players scattered. Nearing base, a message came over the radio for Don to report to the Control Tower upon landing. This he did, and there was the Squadron CO, waiting for him. Apparently, it was the RCAF Headquarter’s team playing soccer and they got our aircraft letter! Well, Don got a condemnation or whatever in red ink in his log book for low flying. Our ‘goose was cooked,’ as they say. We got dirt, right and left, so we all decided we had better get off that Squadron. We decided to try for the Pathfinder Force (PFF), which was far more dangerous than 429 Squadron.

We were back on operations again on 1 February 1945. This time it was to the city of Mainz, some industrial plant. It was just over a 7-hour trip. Once again, lots of flak and search lights, but we got through O.K.

The next night, we went to the city of Wanne-Eickel. Once again, the target was an oil refinery in the Ruhr valley, which was always a hot spot with flak and search lights all through that area. Again, we made it through safely.

On 4 February 1945, we were one of six 429 Squadron aircraft to go on a mining trip to the German port of Wilhelmshaven, where the Germans kept their major warships and U-boats. We flew across the North Sea just above the wave tops and then at the last minute climbed to about 15,000 feet to drop our mines. There were bags of flak, search lights, and fighters. Our aircraft was hit by flak; it sounded like someone throwing rocks at the aircraft. Everything seemed to function alright, but we didn’t know about the undercarriage; however, we returned to base and landed safely.

The next morning we went out to see what damage had been received by our aircraft. Don spotted a big hole through the astrodome; in one side and out the other. Now the Flight Engineer is supposed to stand up in there watching for other aircraft; it’s a very, very important part of his job. We just stared. It was unbelievable – Where had the Flight Engineer been? Just then Dirk arrived. Don asked him, “Where had he been when we were over the target?” He said, “Standing up, looking out of the astrodome.” Don showed him the large hole. The chunk of flak would have taken his head off. We came to find out that Dirk was scared and that he had been curled-up hiding. Don told Dirk that he was through with our crew and we all agreed. Not doing his job could have gotten all of us killed.

Our next operation on the night of 7 February 1945 was to the German town of Gogh and for this raid we took an experienced RAF Flight Engineer, Flying Officer J.W. Carr, DFC. This raid was to prepare the way for the army’s advance across the German frontier near the Reichswald. Over the target, the Master Bomber ordered the Main Force below the clouds; only 5,000 feet. At that height, the bombs exploding from the aircraft ahead of us were throwing us around like crazy. The Master Bomber called the raid off before we could release our bombs and we brought our full load home [8 – 500-lb GP bombs and 8 – 250-lb GP bombs]. Once again, we got through safely.

The next day, our transfer to the Pathfinder Force came through. We did not take a Flight Engineer.

405 Squadron – Pathfinder Force Training & First Ops

On 13 February 1945, we arrived at RAF Station Warboys, which was the Navigation Training Unit (NTU) for new Pathfinder Force (PFF) crews. We were housed as a crew in a Nissen Hut. We had a young WAAF girl as our ‘bat woman.’ I don’t think she trusted us. At 0700 hrs each morning, she would quietly open the door, sticking only her arm in to flick the light switch on, then quickly close the door.

When Ron Moyes was posted to 405 Squadron, the unit was commanded by Group Captain William F. M. Newson, DSO, DFC and Bar. Newson was inducted into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame in 1984 after a stellar RCAF career. Photo

We were at Warboys for a couple of weeks; just time to get used to the Avro Lancaster. The British-built Avro Lancaster Mk. III was a beautiful aircraft to maintain and fly. It carried a huge bomb load for great distances. The Handley Page Halifax had electrically operated turrets; the Lancaster had hydraulically operated turrets which were quite different. The Lancaster’s rear turret had approximately 10,000 rounds, carried in trays up either side of the aircraft, the mid-upper turret had about 5,000 rounds, and the nose turret, which the bomb aimer could use, had roughly 2,000 rounds. As well, our rear turrets had all the perspex cut away for better vision.

Ron Moyes in his hydraulically-operated Nash and Thompson four gun turret. The rear gunner’s position in the Lancaster was a lonely place. Cut off from the other six members of the crew who were stationed in the front of the aircraft, rear gunners like Ron Moyes had an awesome yet terrifying view of the destruction each raid wrought. Most gunners removed the perspex panel for better visibility, leaving them utterly exposed to the extreme cold at 20,000 feet, Photo: Imperial War Museum

The first few days at Warboys, we had lectures. Our Gunnery Leader there told us how we were to proceed if we were attacked by fighters. With our previous experience, we couldn’t believe what he was saying. Upon seeing an enemy fighter, we were told to say the following – and during training he insisted upon it and we were marked accordingly! It was: “Tally-ho, Tally-ho. Rear Gunner to Pilot, Rear Gunner to Pilot. There is a fighter approaching from starboard [or port]. Prepare to take evasive action. Corkscrew starboard [or port]. Go.” During actual operations all we would say was: "Fighter, corkscrew starboard [or port].” Then Don would take the directed evasive action, which was a steep diving turn to port or starboard and, after 15 seconds, he would twist the aircraft back up to where our course had been. In the rear turret, I would be up to the top of the turret, my eyeballs heaven knows where, then, at the twist at the bottom of the dive, it was the very opposite and I would be forced down upon the seat. Don really did a corkscrew which, I believe, saved our lives several times.

While at the NTU, we did some long navigation flights. They also had arranged fighters – ours – to attack us, and in place of ammunition, we had a camera with film that recorded our response to the attacking fighter.

The Walkley Crew after posting to Lancasters with 405 Squadron Pathfinders. Left to right: Kuhl, Moyes, Redinger, Ferguson, Walkley and Farmer. Photo: Moyes Family Collection

We were then sent to 405 Squadron at Gransden Lodge on the border of Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire. The village of Gransden Lodge was actually mixed with the living quarters of the base. The base was a wartime base, one hangar and a bunch of Nissen Huts. One big difference we found here was that the Squadron’s Commanding Officer was a Group Captain, rather than a Wing Commander; the Flight Commanders were Wing Commanders, rather than Squadron Leaders; and the Section Heads were Squadron Leaders rather than Flight Lieutenants. Most crews had already completed a tour of operations; some had completed 45, 60 or even more trips. We had a lot of Australians with us – a good bunch of guys.

We did three training flights around England before going on our first operation. The way the PFF was set up in 1945 was that for the first four or five operations a crew acted in the role of a Supporter; going in on the target at much the same time as the Master Bomber, about a minute or two before ‘H-hour’ (official commencement of the raid). We also carried packages of ‘window,’ which were metal strips about 18" by ½" in a paper bundle. These were thrown out a chute up front in the aircraft as fast as one could throw them out. When they hit the air stream, they scattered, making thousands of images on the ground radar, rendering the radar useless.

The location of the H2S radome on the Lancaster. H2S was the first airborne, ground scanning radar system. It was developed for the Royal Air Force's Bomber Command during World War II to identify targets on the ground for night and all-weather bombing. This allowed attacks outside the range of the various radio navigation aids like Gee or Oboe, which were limited to about 350 kilometres (220 mi) of range from various base stations. It was also widely used as a general navigation system, allowing landmarks to be identified at long range.

After doing the Supporter role, you would be chosen to be either a Blind Bombing crew or a Visual Bombing crew; depending, I believe, on the results of your experience as a Supporter. If picked as a Visual Bombing crew, it meant you would be going in at the start of the raid, to drop your illuminating flares or your marking flares. The Blind Bombing crews came in minutes later, just to continue marking the target, throughout the raid. The Visual Bombing crews carried an extra bomb aimer; one bomb aimer identified the target using H2S radar, the other bomb aimer identified the target visually and he dropped the bombs. Both worked together for accuracy.

While we engaged in a lot of horseplay and ignored rank on the ground, a total transformation took place when we climbed into the aircraft for an operation. Don never had to resort to pulling rank or use the command, “That’s an order.” Everyone had too much sense and self-discipline to require any such nonsense in the air. There wasn’t any saluting or ‘sir-in,’ but a metamorphosis took place once we climbed into the aircraft. We were no longer young men fooling around; just men with serious business at hand, men who set about doing their various jobs with discipline so as to stay alive.

The 405 Pathfinder Squadron operations and planning room at RAF Gransden Lodge, about 16 kilometres west of Cambridge, England. In this busy and smoke-filled room, missions were planned down to the smallest detail, taking into account all variables such as fuel, daily signals, meteorology, intelligence, German defences and bomb fusing times. After planning, the squadron assembled for a briefing before being driven to their aircraft. Photo: RCAF

Our first PFF operation was to Chemnitz, in eastern Germany close to the Czech border, on the night of 5 March 1945 (Lancaster Mk. III, PB653, “V”). Chemnitz had been bombed by the USAAF during the day, we bombed it that night, and the USAAF again bombed it the next day; like Dresden, part of Operation Thunderclap, in aid of the Russian advance. At briefing, we were issued a small cardboard Union Jack with a string to tie it around our necks. If forced to bail out in the target area, we were to walk to the east to meet up with the Russian army. I’ve since read that the aircrew who did this were taken prisoner by the Russians and treated terribly!

For this first trip we had as our Flight Engineer an RAF Flight Lieutenant (F/L), V.G. Hope, DFC. As a Supporter crew, we carried three 2,000-lb bombs, plus three 500-lb bombs. Once again there was lots of flak. When we bombed, the city was clouded over, so our bombing was done using H2S. We understood that the raid wasn’t that successful. For us, the trip to Chemnitz was 7½ hours long.

On 11 March 1945, we were again on operations (Lancaster Mk. III, PB282, “Y”), this time to Essen, the second largest industrial city in the Ruhr Valley. We were once again Supporters. Our Flight Engineer was Pilot Officer A.W. Bishop, RCAF. This was a daylight raid with 1,079 aircraft taking part; the largest number of RAF Bomber Command aircraft sent to a single target yet. We were at the target in the opening minutes and had to orbit it, awaiting the first blue smoke puff sky markers that would mark the aiming point. Our bomb load consisted of one 4,000-lb ‘cookie,’ six 1,000-lb bombs, and three 500-lb bombs. As we reached the English Channel on our return, we saw aircraft that were still going on to the target.

We were one of six aircraft (Lancaster Mk. III, NG437, “M”) from 405 Squadron detailed for a night operation on 13 March 1945 to Erin, a benzol synthetic oil plant in the Ruhr. Once again, we acted as a Supporter crew, and our Flight Engineer was again F/L Hope. The target area was very cloudy and we bombed from 18,000 feet using Gee. Flak was light.

Sixteen aircraft from 405 Squadron took part in a night operation on 15 March 1945 to Misburg, on the outskirts of Hannover; another benzol plant. We were selected as a Visual Illuminator crew for this trip (Lancaster Mk. III, PB282, “Y”). Our Flight Engineer was Flight Sergeant A.J. Newman, RAF, and now we had an additional bomb aimer. Stu, our regular bomb aimer would operate the H2S radar, while our new crew mate was Flying Officer W.H. ‘Bill’ Horsman, RAF, who would drop the flares and bomb the target visually. For this raid, we carried ten illuminating flares that burst just above the target, lighting the ground for other PFF aircraft to identify the target. After dropping our flares, we did an orbit of the target and then dropped our three 1,000-lb bombs. Two large explosions with billowing black smoke were seen, the second explosion lighting-up the cockpit of our aircraft at 15,000 feet. Two 405 Squadron Lancasters failed to return.

The End in Sight

On the night of 16-17 March 1945, we were one (Lancaster Mk. III, ME370, “X”) of 14 aircraft from 405 Squadron that were part of the force of almost 300 aircraft to bomb Nuremberg. This was the same city that had cost RAF Bomber Command 95 aircraft on 30-31 March 1944. So, we were a bit apprehensive on this trip.

This would be an almost 7-hour trip and we encountered the first of what we knew as radar predicated flak as we crossed the Dutch/German border. Directly behind us and at the correct height was a burst of flak. Al and I instantly told Don and he immediately turned 45 degrees to port. Just as we got off track, there was another burst exactly where we would have been. As we approached Nuremberg, we could see a further heavy concentration of flak ahead. Our job was to again serve as Visual Illuminators going in a minute or two ahead of the start of the raid. Commencing our two bombing runs (our flares were dropped from 18,000 feet at 2126 hours and our three 1000-lb bombs were dropped at 2132 hours), the flak was terrible and the Germans were sending up large flares that burst lighting up the whole sky. We also saw aeroplanes being hit; some were direct hits. Aircraft seemed to be going down right and left. I’ll tell you now that I sure prayed that we would make it out of there. I imagine the rest of the crew did the same. There were 24 aircraft lost on the raid.

A Junkers Ju 88 shoots down a Lancaster using the upward-firing schräge Musik system. Illustration Piote Forkasiewicz

At de-briefing, we reported what we had seen, and were told that what we had seen were only “scarecrows”; shells filled with oily rags to appear like direct hits. They said these were a psychological ploy on the part of the Germans, intended to demoralize us. The explosions these “scarecrows” made looked uncannily like Lancasters or Halifaxes with full bomb loads of cookies, target indicators (T.I.’s), or incendiaries blowing up in mid-air. Since then, I’ve learned that the Germans had no such things, and that what we saw were actual aircraft being blown to bits under the impact of a direct hit on their bomb bay. [Editor: What crews were likely seeing was the effect of another German weapon, “schräge Musik.” The Germans had mounted two MG 151 cannons to fire almost vertically upward and slightly forwards from the fuselage of their Me.110 and Ju.88 night fighters. Firing up into the unprotected belly of a fully-laden British heavy bomber from close range, the result was a mid-air explosion and fiery trail to the ground.]

It would be ten days before our crew was again on Ops. It was time for some more leave and training. During the time we were on 405 Squadron, the training was much more concentrated and intense than with an ordinary bomber squadron. Most of our crews had 40 to 80 operations in, and some had more than 100. Like us, a number of crews had been in trouble at their original squadrons for being a little wild. Maybe that was what got them through all this?

During our down time, we would head for the Six Bells Pub. This was the pub used by the Senior NCOs and airmen, as well as the WAAFs and the girls of the Land Army who worked on the nearby farms. The officers frequently went to the Crown and Cushion Pub down the road. I don’t think they had the fun we did. Somebody in our pub would get going on the piano and we would all join in singing.

We returned to Ops with a daylight raid to Paderborn (Lancaster Mk. III, PB282, “Y”) in support of the American Army on 27 March 1945 . We were once again Supporters, but still had our 8-man crew. There was 10/10ths (solid) cloud, but no flak and no fighters. Our H2S went U/S (unserviceable) so, on instructions from the Master Bomber, we bombed on two green smoke puffs from 16,000 feet.

We now had a permanent Flight Engineer assigned to our crew; Flying Officer (F/O) T.H. “Ted” Skebo, DFM, who was on his second tour. Ted had been awarded his Distinguished Flying Medal while flying as a Sergeant with 408 Squadron in 1943. At briefings, I was still looking after the rations to give to the crew during the flight. These rations consisted of six Mars bars and some unsweetened chocolate, plus a handful of very sweet candies. With eight members now in the crew, I had to keep track of who had got a Mars bar to keep everybody happy. This ration presumably dated back to the old days of twin-engine bombers that had 6-man crews – the RAF takes a long time to change things.

On 3 April 1945, we went on another daylight raid (Lancaster Mk. III, PB555, “O”), this time to Nordhausen. The town included a large barracks. [Editor: Unfortunately, the barracks housed a large number of concentration camp prisoners and forced labourers who worked in a complex of underground tunnels where German rocket weapons were being made.] There was 10/10ths cloud at 10,000 feet over the town, so we bombed by H2S. It was difficult to get a good H2S return, so we did four orbits of the target, finally bombing on the fifth.

The next night, 4 April 1945, we were on Ops to Merseberg, the largest synthetic-oil plant in the Reich. This was a 7-hour trip and once again we were detailed as Visual Illuminators (Lancaster Mk. III, PB681, “M”). Three of the four Blind Markers dropped sky markers, but none of the seven Illuminators from 405 Squadron dropped their flares; two bombed on H2S, two on sky markers, one on the glow of fires seen through the cloud, and one on red T.I.’s, We brought our flares back, but dropped our three 1,000-lb bombs on the sky markers. Two large explosions were seen. There were a lot of fighters with tracer flying around, but no one bothered us.

On 8-9 April 1945, we did a night trip to Hamburg, again serving as Visual Illuminators (Lancaster Mk. III, PB282, “Y”). The flak wasn’t too bad. The Master Bomber told us not to drop our flares, as they weren’t required. We dropped our four 1000-lb bombs from 17,000 feet. Two nights later, on 10-11 April 1945, we took part in a night raid to Plauen, a railway centre. On this trip, we were Visual Centrers (Lancaster Mk. III, PB653, “V”). We carried six 1,000-lb bombs, plus the T.I.’s.

On 16-17 April 1945, we were part of a night raid to Schwandorf, another railway centre, again acting as Visual Centrers (Lancaster Mk. III, ME445, “U”). The sky was clear and visibility was very good. The aiming points – the bend of the river, the bridge over the river, and the woods just south-east of the marshalling yards – were all clearly identified. We dropped out T.I.’s from 8,000 feet.

On 22 April 1945, we were part of a Bomber Command force of 767 heavy bombers detailed for a daylight raid against the German city of Bremen. The raid was part of the preparation for the attack by the British Army’s XXX Corps. We were again to serve as Visual Centrers (Lancaster Mk. III, PB282, “Y”). Don took one of our groundcrew engine mechanics along on this raid; the Sergeant had always wanted to see the results of a raid. Of course, this was prohibited, but that didn’t make any difference to Don. As it was, the bombing was cancelled when we were right over the target, due to thick cloud and smoke. We dropped our bomb load in the North Sea.

We were woken at 0400 hours on 25 April 1945 for a daylight raid on Hitler’s country home near the town of Berchtesgaden in the Bavarian Alps. On the very top of the mountain was the famous “Eagle’s Nest.” The site also included the houses of other high-ranking Nazis, including Hermann Göring, and a large SS barracks. As a National Redoubt, it was expected to be defended to the last man. Patton’s Third U.S. Army was approaching and wanted these German troops out of there. It would mean a round trip of 1,400 miles for us, but the chance of getting Hitler was too good to miss.

Takeoff was just after 0600 hours and we again were detailed as Visual Centrers (Lancaster Mk. III, PB282, “Y”). There were only 9 aircraft from 405 Squadron; the Master Bomber and the rest of the PFF came from 635 Squadron. There were more than 350 heavy bombers on this raid, including 16 Lancasters from 617 (Dambusters) Squadron and 17 Lancasters from 9 Squadron carrying 12,000-lb Tallboy bombs. More than 200 USAAF and RAF P-51 Mustangs acted as our escorts.

Flying over the Alps, we thought that this had to be the most beautiful trip we had ever flown. We flew down to Lake Constance, then turned east. Our aircraft was the first to arrive, followed shortly by the rest of 405 Squadron. There was no sign of the Master Bomber, and we couldn’t drop our T.I.’s until he arrived. Finally, we heard the Master Bomber over the radio say that he couldn’t find the target. The main target was to be the big army barracks. We had come in from the west, the target was on the north side, part way up the mountain, and was quite plain for us to see. We then saw the main force approaching from the south. Coming from that direction they wouldn’t see the target until they were almost upon it, and they were getting pretty close. All the 405 Squadron aircraft were just circling the target when Don radioed the Master Bomber and told him that we were in position to drop our T.I.’s. The Master Bomber spotted the target at the same time, but was too far away from the main force which was now arriving. He gave Don the O.K. We dropped our T.I.’s and bombs, then circled. We watched both 617 and 9 Squadrons drop their 12,000-lb bombs, but then the smoke and dust clouded the area.

When we got back to Gransden Lodge just after noon, we were told that Hitler had not been there. He was in the remains of his Chancellery in Berlin, where he committed suicide on 30 April 1945. This raid would turn out to be our last offensive operation of the war.

Home again

Starving Dutch citizens cheer as an Avro Lancaster releases its bomb load of foodstuffs near Ypenburg, north of Rotterdam. The missions went off practically without a hitch. The Germans honored their word, almost entirely, that no coordinated anti-aircraft would fire upon the planes, and countless Dutch civilians benefited from this “manna from heaven.” In one week the combined efforts of the RAF, RCAF, RAAF, RNZAF and the USAAC (they called it Operation Chowhound) dropped over 10,000 tons of food on the starving and grateful Dutch. One of those who had survived the “hunger winter” and benefited from the flights was the malnourished granddaughter of the former mayor of Arnhem, a teenaged Audrey Hepburn. Photo: via nationalww2museum.org

405 Squadron’s work as Pathfinders was not quite over. On 7 May 1945, we took part in Operation “Manna.” The people of Western Holland were facing starvation. With that part of Holland still in German hands, a truce was arranged with the local German commander and Lancasters were used to drop food supplies to the civilian population. Eight 405 Squadron Lancasters marked the aiming point for other Bomber Command aircraft to drop food to the Dutch at Rotterdam. Takeoff was just before 1300 hours (Lancaster Mk. III, PB282, “Y”). We would act as a “Backer Up,” and carried red Target Indicators. We dropped these from just 350 feet above ground onto a white cross that had been placed in a field to mark the dropping area. At that height, we could see the people waving. (Note: Bomber Command flew 2,959 flights, dropping 6,672 tons of food during Operation “Manna.”)

On 9 May 1945, V-E Day, the crew flew to Lubec, Germany (Lancaster Mk. III, ME445, “U”); one of eight 405 Squadron aircraft detailed to pick up newly released Allied prisoners of war (PoWs) and return them to England as part of Operation “Exodus.” (Note: Over the next week, 41 sorties were flown by 405 Squadron to repatriate 947 PoWs.) Only skeleton crews were required, so I stayed at base. The 23 PoWs Don returned on that flight were in a pretty sorry state. On the way back, Don swung off track to fly over London to show them Buckingham Palace. This was strictly against regulations and Don was reminded of this after returning to base!

With the rest of the crew away picking up the PoWs, I went over to the village green with the rest of the station personnel. There, the village people had placed barrels of beer and food to celebrate V-E Day. Also, four huge search lights had been positioned at the corners of the green for night time use. By the time the crew got back from Lubec, I was feeling pretty good.

Everybody was in a joyous mood by evening. Al and I spotted Don taking a young WAAF across the field, knowing he was up to no good. So we went to a search light and lowered the beam on the two of them. I don’t know what happened, but we accidentally tipped the light over and there was a great smash as it broke all to pieces. We got out of there in a hurry.

To add to the celebrations, some crew mates went out to the aircraft to get the Verey Pistol and cartridges. Then, they drove around the countryside firing the flares into hay and wheat stacks. Soon, there were fires burning away all over the place. Of course, the Canadian Government probably had to pay for these later. (Note: A website devoted to the village of Gamlingay, just south of Gransden Lodge, cites a Mr. N.J.R. Empson, who recalls “Canadian airmen firing Verey Lights into the sky. They also fired them into two of Harold Jefferies’ corn stacks at Fuller’s Hill farm and set them alight.”

Air Vice Marshal “Black Mike” McEwan and his dog Blackie. Note the Malton Mike name under his command flag on the Lancaster behind him. Then sobriquet came after one of his earlier visits to the AV Roe factory in Malton, Ontario to view the Lancaster X assembly line. Though Moyes’ story does not mention it, it is likely that Ashby was flying M-Malton Mike on the transatlantic flight with the Air Vice Marshal on board as the second pilot, as it is documented that McEwan accompanied his dog back to Canada.

Soon after V-E Day, 405 Squadron rejoined No. 6 Group. The squadron was one of eight RCAF bomber squadrons picked to go to the Far East to carry on the war against Japan. 405 Squadron would be teamed with 408 Squadron to form No. 664 Wing. On 22 May 1945, a parade of all ranks was held at Gransden Lodge and Air Vice Marshal (AVM) Don Bennett, the Air Officer Commanding the Pathfinder Force, thanked the squadron and wished us “Bon Voyage.” Leaving our aircraft behind, we boarded a train on 26 May 1945 for Linton-on-Ouse, where 408 Squadron was already stationed.

While at Linton-on-Ouse, 405 Squadron would convert to the Canadian-built Lancaster Mk. X. From 1 to 13 June 1945, we had a heavy program of both ground and air training to prepare us for our trans-Atlantic flight home. By the middle of June, we were all set to fly the aircraft back to Canada, via the Azores to Newfoundland and New Brunswick.

With our kit bags packed, at 0900 hours on 16 June 1945 we boarded our aircraft (Lancaster Mk. X, KB957, “W”) to begin the trip home. By 0920 hours, the twenty 405 Squadron Lancasters and six aircraft from 408 Squadron (15 had departed on 14 June) had set course for Canada. Each aircraft carried a couple of ground crew as passengers. Our first stop was RAF Station St. Mawgan, Cornwall, where we stayed the night. Early the next morning, we took off for Lagens Field (present-day Lages) in the Azores. There, we refuelled for the long ocean flight to Gander, Newfoundland.

Crossing the Atlantic, we flew alongside Flying Officer W.G. Ashby’s Lancaster. Ashby had been given the job of sneaking AVM ‘Black Mike’ McEwen’s puppy back to Canada. About half way across, Ashby reported a fire in one of his engines. The internal fire extinguisher put the fire out, but now he had only three engines. We slowed down so that he could keep up with us. About 100 miles from Gander, another of his engines gave out. The airwaves were ‘hot,’ with everyone worried about how the puppy was doing. I guess Ashby’s crew was wondering, “What about us?” We stayed with them until they reached Gander safely. We stayed the night at Gander and the next morning took off for Scoudouc, New Brunswick. On our arrival there, we were issued leave passes and train tickets, and were told to report to Greenwood, Nova Scotia, in 30 days.

Arriving at Greenwood near the end of July 1945, we found the base crammed with personnel. No. 664 (Heavy Bomber) Wing was officially formed at RCAF Station Greenwood on 1 August 1945. But before anything could come of going to the Pacific, the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the war against Japan was over. We sat around for a couple of weeks while they figured out what they were going to do with us. Finally, we were offered our discharges on 19 September 1945. I said my ‘Good Byes’ and wished everyone well. My war was over.

50 or so Canadian-built Lancasters line the ramps at RCAF Station Scoudouc, New Brunswick, one of which is likely Moyes’s Lancaster Mk. X, KB957, LQ-W Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Life as a postwar armourer

In August 1946, the RCAF introduced a new course, known as the Long Term Armament Course. The first course commenced the first week of August 1946. Its duration was for one year. Each month a new course was started. The last one began in February 1947, for a total of seven courses. I was on Course No. 6.

The make up of the courses was about 85% ex-aircrew up to the rank of Flight Lieutenant (F/L) – pilots, navigators, bomb aimers and air gunners – many had DFCs or DFMs, others were ex-PoWs. In fact, on Course No. 1, there was a F/L Air Gunner, DFC and bar. In the middle of September 1946, came Reversion Day; all the students were reduced to the rank of Leading Aircraftman (LAC) and given a Group 1 Provisional Trade Grouping, which was the lowest possible.

Courses included machine shop bench work with lathes, milling machines, etc. There was instruction on the turrets and all the types of guns used in aircraft and on the ground by the U.S., British and Canadians. We learned all the various types of ammunition and flares, including their storage, handling and transportation. We learned all the types of explosive – TNT, Shellite, Tungsten, etc., – and the operation of some 33 types of bomb fuzes. We learned about bombs and their make up – from 11½ lb to the 22,000 lb – and we learned their carrier and release systems

I graduated in December 1947. Half of the Course was sent to the Winter E E Flight at Watson Lake, BC, for the winter. I remained at Station Trenton, where we had a Lancaster, Ventura, Mitchell, Mustangs, Vampires, and Harvards; all used by pilots in training at the Air Armament School. In 1951, I was transferred to 420 Squadron at Station London, which was equipped with Mustangs.

130 North American Mustangs equipped several RCAF reserve fighter squadrons after the war including Moyes’ 402 from 1951-1957

Ron Moyes at RAF North Luffenham in 1953 serving as an armourer with 401 Squadron on Canadair Sabres. Following the war, most airmen were rank reduced if they chose to remain in the RCAF. Moyes re-upped as a Leading Aircraftman, but by the time off this photo he had made Corporal. Note the chest full of service decorations and his Operational Wings indicating he had completed a full operational tour with Bomber Command — an achievement that defied terrible odds for a rear gunner. Photo: Ron Moyes Collection

In 1953, I was transferred to 410 Squadron with 1 Wing at North Luffenham, England, equipped with Sabre 1s. While there, we went as a squadron to a big gunnery school at Acklington. We were there for a month. Later that summer, seven of us were sent over to RAF Coltishall for six weeks, where we serviced drogue-towing Sabres during 1 Wing’s gunnery exercises.

Returning to Canada as a Senior Non-Commissioned Officer (Sr NCO), I was back at Trenton for a brief period, before going to Camp Borden as an Instructor. There, with two other Sr NCOs, we conducted Bomb / Explosive Courses over at No. 13 Explosive Depot, Angus. These courses, composed of both NCOs and officers, were taught how to cut 500 lb bombs open; cutting using explosives. We also taught the 750 lb nuclear air-to-air rocket that was for use at some of our Air Defence Command Stations.

In 1962, I was transferred to 3 Wing, at Zweibrücken, Germany, as the nuclear strike CF-104s were soon to be received. While waiting for the CF-104s to arrive, I was put in charge of the Explosives Area, and required to get rid of all the 2.25 inch rockets left from the CF-100s.

The Commanding Officer also put me in charge of destroying the station should Germany be invaded. Remember, this was the Fall of 1962, when the Missile Crisis in Cuba was on, and things in Air Division were pretty hot. I had ten 1,000 lb bombs on hand to crater the runway, etc., and I had to destroy all the communication systems too. The crew and I were to be the last to leave the station.

On the arrival of the CF-104s, we had about 90 Armourers on base, including 48 trained on loading and unloading the 2,000 lb nuclear bombs on the aircraft. These 48 Armourers were divided into four man bomb crews. They had to carry out the certification checks on the aircraft every time someone disconnected an electrical plug, or removed a pylon or fuel tank. They also provided a crew for the Quick Reaction Alert aircraft, where we had four CF-104s sitting with nuclear bombs installed. With the pilots, the crews remained in the enclosed secure area for two weeks at a time; their meals were brought to them and they slept there for that period.