LAST CALL FOR LANCASTERS

As the Second World War wound down in Europe, the Allied powers, which had previously been focused on the destruction of Hitler’s Nazi-run Germany, began to think about the battle to come in and around Japan. The United States was largely responsible for offensive aerial attacks on the Japanese home islands, though the Royal Navy and the aerial arms of Australia, New Zealand, Great Britain and Canada were engaging the collapsing enemy in his many empirical outposts from Burma to Palembang to New Britain.

Plans were put in place to turn to the east with as much assistance for the Allies in the Far East as the Commonwealth could muster. Once they had brought Nazi Germany to its knees in final surrender, massive amounts of men and war machines could then be unleashed on Japan to speed the end of the war in that theatre. It was largely held by the Allies everywhere (except for those who were secretly working on the atomic bomb) that this war would be fought to the last Japanese soldier on the home islands of Nippon.

After D-Day, when Churchill met with Roosevelt during the second Québec Conference on 12 September 1944, he made a promise to transfer a substantial number of Bomber Command heavy bombers to the Pacific Theatre—up to 1,000 aircraft. As the European war’s outcome was not in any doubt, except for the day of final surrender, Bomber Command set about in October to create the structure of a new bomber force, code-named Tiger Force.

Initially this new and powerful force was to be formed with 22 squadrons into three groups (9 Wings total) with squadrons from the Royal Air Force and the air forces of Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Later the force was reduced to just 12 squadrons and then to a final eight squadrons in two groups, with only RAF and RCAF squadrons. When deployed, Tiger Force would fly the highly capable Avro Lancaster and the Avro Lincoln (just coming off the assembly line) as well as American-built Consolidated Liberators. These new Commonwealth squadrons on the scene in Okinawa would need fighter escort, which was to be supplied by the RAAF’s Australian First Tactical Air Force as well as other Commonwealth units already in theatre and American assets.

Royal Canadian Air Force squadrons involved kept their old Bomber Command 6 Group designation, and the operational wings were to be formed up at the following bases:

661 Wing commanded by W/C F.R. Sharp DFC; Yarmouth, NS; 419 and 428 Squadrons; 15 Jul–5 Sep 1945;

662 Wing commanded by G/C J.R. MacDonald DFC; Dartmouth, NS; 431 and 434 Squadrons; 15 Jul–5 Sep 1945;

663 Wing commanded by G/C J.H.L. Lecomte DFC; Debert, NS; 420 and 425 Squadrons; 1 Aug–5 Sep 1945; and

664 Wing commanded by G/C W.A.G. McLeish DFC; Greenwood, NS; 405 and 408 Squadrons; 1Aug–5 Sep 1945.

The colour scheme for Tiger Force aircraft was to be white upper surfaces with black undersides. This scheme, despite the cancellation of operations against Japan, was apparent on many postwar RAF Lancasters and Lincolns like this 35 Squadron aircraft. Photo: RAF

Tiger Force Fuel. The earliest planners for long-range bombing of Japan by Commonwealth air forces began thinking in 1943 about how Lancasters would get to Japan when there were no bases in striking distance. The Air Ministry dabbled with converting Lancs into flying tankers, capable of refuelling other Lancs en route. The eventual capture of suitable air base islands by the Americans made the idea unnecessary, but two Lancasters were converted as tankers and two as receivers to develop aerial refuelling.

Two additional British-built airframes were modified to accept a 1,200 gallon dorsal saddle tank mounted aft of a modified canopy for increasing range. The aircraft were evaluated in India and Australia in 1945 for possible Tiger Force use in the Pacific, but the tank adversely affected the handling characteristics when full and was deemed a failure. Given the defensive mid-upper gun turret was removed to accommodate the enormous tanks, there was no way to counter an attack from above. One can only imagine what kind of flying blowtorch this aircraft would have been should a Japanese fighter pilot score just one hit or if a flak shell burst above. Both Lancasters would have a date with the scrapper’s blade in 1946. Photos via Brit Modeller

Related Stories

Click on image

On 31 May 1945, three weeks after VE Day, the European Allies got set to get right back into the fight against the Japanese. Here we see RCAF Air Vice-Marshal “Black Mike” McEwen, Commander of 6 Group, Bomber Command (foreground) and Air Vice-Marshal Arthur “Bomber” Harris at RAF Middleton St. George, waving goodbye to the first of 141 Canadian Lancasters that would fly to Canada, via the Azores, over the following weeks. Air Vice-Marshal Clifford Mackay McEwen, CB, MC, DFC and bar, was a First World War fighter pilot with 22 aerial victories. During the 1920s at Camp Borden, Ontario, he acquired the nickname “Black Mike”, due to his tendency to suntan very quickly. One of the Lancs destined to join Tiger Force assets back in Canada was Lancaster KB999, the 300th Canadian-built Lancaster. When it came off the assembly line in Malton, Ontario, Victory Aircraft Corporation production staff dedicated this aircraft to McEwen and had his pennant painted on the nose with the words Malton Mike. After the end of the war, it was decided that KB999 Malton Mike should have the honour to fly McEwen back to Canada. Malton Mike was assigned to the RCAF’s 405 Vancouver Squadron, painted code letters LQ-M, and returned the Air Vice-Marshal to Canada on 17 June 1945. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

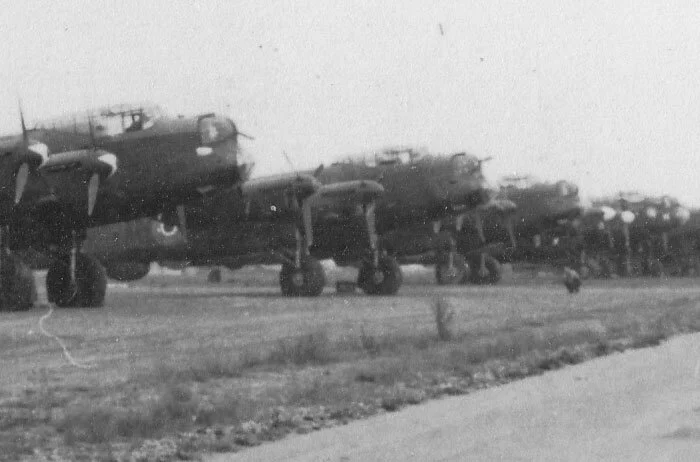

Royal Canadian Air Force Lancaster 10s (all built by Victory Aircraft in Malton, Ontario) line the taxiway at RAF Middleton St. George as crews assemble before their mass departure for Canada via the Azores. Over the following weeks, 141 Lancs would make the journey. Aircraft and crews await the arrival of dignitaries, such as Bomber Harris and Black Mike McEwen, there to see them off. The black and white checkered control building at top centre is where Harris and McEwen’s entourage would arrive. RAF Middleton St. George, in Durham County, England was the main base of 6 Group (RCAF) of Bomber Command and home at one time or another to 419 (Wellingtons, Halifaxes and Lancasters), 420 (Wellingtons) and 428 (Wellingtons, Halifaxes and Lancasters) squadrons. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A terrific overhead shot of the crowd of RCAF and RAF airmen surrounding a staff car and its occupants, Bomber Harris and Black Mike McEwen. Lancasters of 419 Moose Squadron and 428 Ghost Squadron are serviced and fuelled for the 2,600 kilometre flight over water to the Azores. Over the next few months, 141 Lancs would make the transatlantic flight. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A close-up of the preceding photo reveals a relatively new Lancaster, with only over-wing exhaust streaks to mar her clean paint. NA-F was a 428 Squadron Lancaster. The squadron crest features a human skull displayed within a black shroud and the motto of the squadron is “Usque ad finem” (“To the very end”). The nickname “Ghost” came from the numerous hours of night bombing that the squadron carried out. Nearly 200 decorations for valour were awarded to the aircrew of 428 Squadron during the Second World War.

As the war wound down, the Canadian squadrons of 6 Group were being re-equipped with Canadian-built Lancaster bombers so that at the outset of Tiger Force training, they would all have the same equipment. 141 brand new or relatively low-time Lancaster 10s were assigned to Tiger Force, though many of them still had not even been delivered to the RAF.

Following the end of the war in Europe, the Lancaster Mk.10s in service with the RCAF were flown to Canada by their crews, set to be modified, painted and crewed for Tiger Force operations. Flying out of England over a period of several weeks, they journeyed to the Azores and from there to airbases in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and, finally, on to the big Repair Depot at RCAF Scoudouc, New Brunswick. Only one aircraft was lost, ditching in the ocean off the Azores, but no airmen were lost.

Soon, the atomic bombs put a quick end to the requirement for additional Canadian and British bombing crews and aircraft. Tiger Force stood down and ceased to exist after October 1945. Without a Canadian requirement for a heavy bomber force, the scores of Lancasters harboured in Scoudouc were going nowhere. It was soon realized that the Lancasters would not fare well stored in the humid and salty ocean air of Scoudouc, and were prepared for a ferry flight to drier air in Alberta. That province had many recently closed air bases from the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan that were ready to be fired up again to accept the aircraft and mechanics to keep them relatively healthy until a plan could be made for their disposal or further use. Eventually all the 140 or so Lancasters were delivered to Alberta, but on one single day in September of 1945, the skies above the tiny hamlet of Pearce, Alberta and its nearby training base absolutely thundered with the arrival of 83 Lancasters over the one afternoon. Pilots and aircrew, realizing that they would likely never fly a Lancaster again, ripped the blue prairie skies apart, turning, banking, zooming, flying low level, and scaring farm animals until they had no fuel left.

After the Lancasters were brought to Pearce, crews on the ground were tasked to keep them flyable, starting their four Merlin engines daily and looking after leaks and dried seals. To relieve space at Pearce, many Lancs were dispatched to other outlying airfields like Fort McLeod, Penhold, and Calgary. For some, this would be the end, eventually struck off charge, stripped of their valuable engines—some sold for scrap, some sold to farmers for the contents of their fuel and glycol tanks or handyman projects, or even just to have one. You could buy a Lancaster with all four Merlins for just $250.00 to $350.00. The lucky ones, more than 70 in all, would be selected for new roles as anti-submarine patrol aircraft, ice reconnaissance or photographic mapping. In these new roles, they flourished, becoming part of the rich history of the RCAF. Eventually, within ten years, most of even these Lancs were obsolete and they too ended up back in Alberta for further storage and eventual scrapping.

But it is the Lancasters which were not selected for a new life, the ones not sold immediately for scrap or towed away by farmers that were the saddest of all. They lingered out on the cold Canadian prairie, hulks stripped of their valuable bits, sinking on deflated tires, their painted bombing mission markings fading and flaking under the onslaught of long, terrible winters and the hot prairie sun. By the late 1950s, they were simply a boneyard, picked over by maintenance crews, collectors, museums, vandals and gawkers. Their humiliation complete, these truly venerable warhorses simply vanished from sight by the 1960s, finally cleaned up like some toxic waste dump.

But the memories remain. If you drive out to the now-ghost town of Pearce, Alberta on a fine fall afternoon, the wind rippling the wheat and canola like an ocean swell, and you stand silent on the old runway, ear cocked to the prevailing wind, you will hear them—the 83 joyous crews laughing, the Merlins howling a warrior’s cry, bellowing over the prairie, the popcorn backfires and rubber chirps as they settle onto the runways upon which they once trained for the fight.

Listen over the sound of the prairie wind. Listen. You can hear the pinging and ticking of cooling exhaust stems, the laughter of crews taking one last photo together. You can hear them promising to stay in touch.

And then the sound of silence.

On 8 June 1945, after a 2,600 kilometre leg to the Azores, followed by a 3,500 kilometre journey to Nova Scotia via Gander, Newfoundland, 428 Ghost Squadron Lancaster NA-D for Dolly drops nicely onto the runway at Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, en route to Scoudouc (pronounced Skoo-duke), New Brunswick along the shores of Northumberland Strait. Lancaster Dolly was the third 428 Squadron Lanc with the NA-D code. The first was lost on a night raid on Hagen when heavy icing caused it to force-land in France, killing its Navigator and Flight Engineer. The Lanc which replaced it in the flight line was also lost during a raid on the Hirth aircraft engine plant in Stuttgart in January 1945. That aircraft was shot down by a night fighter, with only two crew members surviving to become POWs. This Lancaster with the name Dolly (KB843) saw 32 bombing missions, but the last one had the most historic significance. As NA-D in RCAF 428 Ghost Squadron, it was the last Group 6 Bomber to land and last RCAF bomber aircraft to log combat time in the Second World War. This Lanc was destined to become part of Tiger Force’s 661 Heavy Bomber Wing at Yarmouth, Nova Scotia. Like all Tiger Force Lancs after the Japanese surrendered, it was stored in Alberta (Calgary), but then sold for scrap in May of 1947. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

On 5 June 1945, the crew of Lancaster KB-739 Zoomin’ Zombie (NA-Z) celebrate their successful crossing of the Atlantic from the Azores on their way to Scoudouc. Beneath the Zoomin’ Zombie title she also sports the Latin phrase “Cui Bono?”— “To whose advantage?” Under these nose art titles, this Lanc completed 56 combat ops. The members of the crew include Cliff Pratt (P), Gord Claire (FE), Jim Gunn (N), Doug Miller (B), Archie Martin (WAG), W.A. Magee (WOP), Ted Dykes (AG); along for the ride home were Les Powell (PR) and Hal Baddock (RT) assigned to Tiger Force, 661 Heavy Bomber Wing, Yarmouth, NS. She was last seen in a scrapyard in Edmonton, Alberta. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

An overhead shot of RCAF Station Yarmouth after the war. Looking straight down, we can see 18 large four-engined aircraft that appear to be Lancasters, stored in front and between the hangars on the flight line. There were other aircraft as well across the field, but we enlarged just this portion. The plaque at the former East Camp site of RCAF Station Yarmouth states that Yarmouth was used by RCAF Tiger Force in 1945. This confirms that these aircraft were indeed Lancasters either in storage or on their way to Scoudouc or Pearce. Yarmouth was built to house the Royal Navy Telegraphist/Air Gunnery School. Photo via Joe Hine Collection

Over the next weeks, Lancasters would arrive at Scoudouc, New Brunswick, home of No. 1 Maintenance Wing and No. 101 RCAF Equipment Park. Being photographed on 2 or 3 June 1945, this is likely the first group to arrive, judging by the crowd of depot workers and New Brunswickers turned out to meet them. With its white spinners and the big crowd, this may be Lancaster KB941 (PT-U) of 420 Squadron, the first to arrive. She landed as a Tiger Force Heavy Bomber and a couple of years later at Penhold, Alberta was towed away by a farm truck to be used for anything from flower planters to outhouse doors. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

With gawking crowds and photographers all around, the pilot of Passion Wagon (KB941) shuts down his still spinning propellers. Tired as they may have been, it must have made them proud to arrive back in their beloved Canada in this kind of martial style. This aircraft had, just two months before, been ferried from Canada to England and No. 32 Maintenance Unit at RAF St Athan, Glamorgan, Wales. It saw no combat and returned to Canada as PT-U—part of 420 Snowy Owl Squadron, RCAF. It was soon in storage at Penhold and then to Claresholm, Alberta. It was struck off charge in 1947. There is a photo of it being dragged away by a farmer later in this article. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Lancaster Rabbit Stew (KB903), with three of its engines still running, comes to a stop at Scoudouc with lots of RCAF personnel watching. Whereas American nose art was randomly selected by the aircraft’s first commander or crew chief, nearly all the nose art found on RAF and RCAF bombers related to the aircraft code. For instance, NA-Z was Zoomin’ Zombie, WL-P was Piccadilly Princess and WL-B was Bluenose Dads. So why was Lancaster 420 Squadron PT-P called Rabbit Stew and why did it have the letter R on its nose? The reason was that it was originally assigned to 425 Squadron Les Alouettes as KW-R. It never saw combat and was reassigned as a Tiger Force Lanc to 420 Squadron as PT-P, crossing the Atlantic still wearing the Rabbit Stew markings. It was one of two RCAF Lancs called Rabbit Stew, the other being KB882. Both were included in the many Lancasters which would survive the war as well as the scrapper’s torch, KB903 being modified to Mk10-MP (Maritime Patrol) standard, and KB882 modified to Mk10P (Photographic) standard. KB882 exists to this day as a gate guardian at the Edmunston, New Brunswick Airport. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Dozens of low-time Lancasters, fresh from combat or at least European operations, sit on the grass at Scoudouc’s Repair Depot and Equipment Park, where they were to be modified as Tiger Force Lancasters for the coming battle against Japan. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A close-up of the Repair Depot flight line at Scoudouc, New Brunswick. The all-white prop spinners belonged to aircraft of 420 Snow Owl Squadron. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Lancaster KB864, Sugar’s Blues, was a relatively new airframe, having flown to England in January of 1945 and been allocated to 428 Ghost Squadron, RCAF. Sugar’s Blues’ nose art, a copy of the famous pin-up girl by legendary pin-up artist Alberto Vargas, was painted by squadron artist Tom Walton. Sugar’s Blues became well known in Canada as this aircraft was chosen for a cross-Canada bond tour. The 21 bombing mission marks, which would have been normally bomb silhouettes, are here replaced with a silhouette of a diving female. It is clear from this photo that the Scoudouc Repair Depot had expected the bombers to stay a while as the tires have been covered in custom made tarps, designed to protect the rubber from deterioration in the sun. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A painted replica of the nose art from the Sugar’s Blues Lancaster of No. 428 Squadron RCAF. The figure is based on the popular Alberto Vargas pin-up girl featured in the January 1945 edition of Esquire magazine. Since the aircraft’s squadron code was NA-S, her call sign would have been “S for Sugar.” Sugar’s Blues got its name from a popular wartime dance tune. Each of the diving figures represents a successful operation. The artwork on KB864 was painted by Wireless/Air-gunner Sgt. Tommy Walton. The replica painted on the Bomber Command Museum of Canada’s mock-up is the work of nose art historian and artist Clarence Simonsen.

A close-up of NA-S, Sugar’s Blues, on the Scoudouc flight line along with dozens of other Lancs. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Not all the Lancasters were in pristine condition as witnessed by this rather battered looking Lanc (KB839), nicknamed Daisy. Though she started her combat career as SE-G with 431 Squadron RCAF (now known round the world as the Canadian Forces Snowbirds), she then was reassigned to 419 Moose Squadron as VR-D. Small dog silhouettes (presumably Daisy the dog) tell the story of Daisy’s 26 combat operations. She was returned to Canada in the first week of June 1945. It was then flown to Avro Canada at Malton for a conversion to Mk10-AR specifications—an Area Reconnaissance aircraft. Conversion included adding equipment such as six camera positions, search/navigational radar, electronic surveillance aerials, and new nose and rear fairing, with the survival equipment in the rear turret. It would go on to a long career, flying with 405 and 408 maritime squadrons. It exists to this day at the Greenwood Military Aviation Museum in Nova Scotia. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Not all the Tiger Force Lancasters met an unworthy fate out on the Alberta prairie. The former 419 Squadron VR-D for Daisy (KB839) was selected for modification to the Lancaster Mk10-AR configuration as an Area Reconnaissance patrol aircraft. Here we see her at Naval Air Station Jacksonville, Florida, in February 1953. It served with 405 Maritime Patrol squadron in 1952 (new aircraft code VC-AGS). It was retired on 23 June 1955. Photo via Ronnie Bell Flickr

Lancaster KB839, the former D for Daisy of 419 Squadron and a 26 mission veteran and Cold Warrior, is now on display at the Greenwood Military Aviation Museum at the RCAF’s 14 Wing in Greenwood, Nova Scotia. It is displayed in the markings it once wore as a Maritime and Area patrol aircraft postwar, until it was replaced by the two-turning/two burning engines Lockheed Neptune. KB839 is the only Lancaster in Canada today that sustained battle damage during the Second World War. Photo by Andre Eisnor

Another Lancaster Mk10 parked at Scoudouc after crossing the Atlantic—420 Squadron's PT-N, No Drip Nan (KB923). Not sure I want to think about that aircraft name too hard, but perhaps it is because she had tight engine seals and her Merlins never dripped oil, which is of course unlikely. No Drip Nan was delivered to England and assigned to 420 Squadron late in April and just six weeks later she was back in Canada at Scoudouc, assigned to Tiger Force at Debert. She clearly had no time to see combat and her postwar career was not much better—put in long-term storage at Pierce, Alberta, then used as an instructional air frame in 1946 and struck off charge in December 1948. She wears crew names on her sides NIC, HOE, RICH, and GUS (on engine). Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A good look at the jumble of Tiger Force Lancasters at the Repair Depot at Scoudouc from the roof of a hangar. We can see maintenance men eating their lunch beneath Lancaster PT-G in the middle ground. These are mostly 420 Snowy Owl aircraft, which can be determined not just by their PT squadron code, but by the white propeller spinners and the white owl flying on the facing sides of the vertical stabilizers. Tarps cover some glass areas such as the top turrets and some cockpits. In the far distance is a line of Harvard trainers. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Bomber Service — a Lanc story

Another Lancaster by the name of Hell Razor sits on the Scoudouc storage line. Its nose art shows a bat-winged creature with a jagged straight razor for a beak and a machine gun spitting bullets from its mouth whilst dropping bombs from its clawed feet. The Bomber Command Museum website has a powerful story about Hell Razor: Lancaster Mk. X KB885 was built at the Victory Aircraft Plant at Malton, Ontario and ferried to a maintenance unit in England. It was assigned to No. 434 [Bluenose] Squadron in March 1945 and the markings WL-Q were painted on the fuselage. The number of operations flown by KB885 with No. 434 Squadron and their details is not known. In April 1945, the aircraft was transferred to No. 420 [Snowy Owl] Squadron based at Tholthorpe, Yorkshire, England. Here the aircraft was assigned the code letters PT-Y.

However the war in Europe ended before KB885 could fly combat operations with its new squadron. No. 420 Squadron returned to Canada on 14 June 1945, and prepared for duty in the Pacific as part of “Tiger-Force.” The dropping of the two atomic bombs and the total surrender of Japan ended the Second World War on 15 August 1945. No. 420 Squadron was disbanded at Debert, Nova Scotia on 5 September 1945.

On 8 September 1945, KB885 arrived at Pearce, Alberta together with 82 other Canadian-built Lancaster veterans. In the next three months all these aircraft were flown to different RCAF bases in Alberta and placed into long-term storage. KB885 was flown to what was formerly #37 Service Flying Training School in Calgary and placed in a hangar. In 1947, the Canadian Government decided to sell a number of Lancasters. The RCAF struck KB885 off strength and sold it to C.R. “Charlie” Parker of Red Deer, Alberta for $275.00. The aircraft was flown to Penhold (formerly the site of #36 SFTS under the BCATP), where she appeared at an open house air show on 11–12 June.

Health reasons forced Charlie Parker to sell “Bomber Service” in 1954. Two years later, the business was purchased by Walter Mielke. Mr. Mielke was approached by Troutdale Airmotive Company of Troutdale, Oregon, who offered to purchase the Lancaster for $6,000 and convert it into a fire-fighting water bomber. The offer was accepted on the condition that Troutdale purchase a surplus P-40 Kittyhawk from the RCAF base at Vulcan and move it to “Bomber Service” to replace the Lancaster

Preparations then began to make the Lancaster airworthy and ferry KB885 to California for licensing and then to Portland, Oregon to be modified to become a water bomber. The cost to prepare the aircraft for flight was estimated to be $14,000. James Sproat, a Portland pilot who was to fly the aircraft to California, was reported as saying that the bomber was to carry 4,000 gallons of water and would be able to lay a 200-foot swath of water one inch deep in the path of an advancing fire.

The weather was good in the fall of 1956 as two air force mechanics from the Penhold base assisted with preparing KB885 for flight. New Rolls-Royce Merlin engines were fitted and run-up, the elevators, ailerons, and rudders were refurbished, new tires were installed, and a makeshift runway was bulldozed in a nearby field.

Charlie saw his new Lancaster as a potential magnet to draw customers to his service station on Highway #2, about one mile south of Red Deer. His daughter, Lois Gilmour recalled, “Dad was always full of ideas that were different. He could fix or build almost anything, really a great inventor of machinery, etc., and loved cars and planes. I’m sure people around here wondered about him—but they were in awe when he set his plan in motion.” Mr. Parker began to tow his new bomber from the Penhold base on country roads and across farm fields. For a time it was bogged down in wet ground but finally, after the ground froze, it completed its trip to Charlie’s gas station that he named “Bomber Service.”

The Calgary Herald reported that, “When the engines were started, early morning motorists who probably had no thought that the machine would ever fly again, stopped to confirm their disbelieving eyes. Nearly everyone who went by slowed their cars to a crawl as they watched the propellers cutting through the air.”

But a happy ending to the saga of KB885 was not to be. As the big moment arrived in January 1957, pilot-mechanic E. Robinson taxied the Lancaster through the snow to her new runway. Just before take-off, hydraulic problems developed and, while Robinson worked on the hydraulic system, a fire ignited in the interior of the nose section. Before it was extinguished the complete nose section burned off and fell to the snow. The once proud bomber was towed back to the service station and later sold for scrap. Both photos via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection–Colour photo by Rob Taerum

One last look at a Lancaster at Scoudouc, New Brunswick—this one Lancaster KB872, NO! NOT NOW. She sports a copy of the same Alberto Vargas pin-up as did Sugar’s Blues. This was a 431 Squadron Lancaster with aircraft code SE-N. Delivered to England in February of 1945, it was assigned to 431 and then to 434, but was back with 431 and assigned to Tiger Force with 434 at Debert. Instead, like all these Lancs, she lingered at Scoudouc, then was flown to Alberta for long-term storage and then struck off charge in 1947. Given her career, her nose art of NO! NOT NOW, was incredibly apt. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

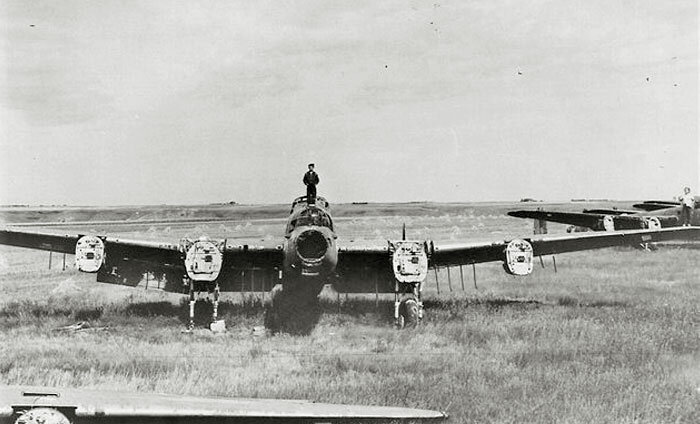

Up until Karl Kjarsgaard recommended that I look into this story about Tiger Force Lancasters and the Alberta boneyards, I had never even heard of the Repair Depot at Scoudouc, New Brunswick. I did however have this photograph in my miscellaneous folder which I have never been able to find information on. I had just assumed it was one of the Alberta BCATP bases which would later be used for long-term storage of the Tiger Force Lancasters. On showing this to Karl, he was quick to identify it as Scoudouc, New Brunswick. Scoudouc was originally established in 1940 as a relief landing field for No. 8 SFTS at Moncton. In September 1941, the aerodrome changed its function when it became the home of No. 4 Repair Depot, which later relocated to RCAF Station Dartmouth, and No. 1 Radio Direction Finding Maintenance Unit** (No. 1 RFD MU), a top-secret maintenance unit. Scoudouc was the home of No. 1 Maintenance Wing which performed most of the second and third line maintenance on the Home War Establishment aircraft in Eastern Canada. In fact, 162 Squadron in Reykjavik, Iceland flew their Cansos to Scoudouc for heavy maintenance on completion of which the aircraft returned to Iceland. There is no doubt that Tiger Force Lancasters landed at Scoudouc for a variety of reasons but none of the Tiger Force Wings formed there. In 1945, the station was renamed RCAF Station Scoudouc. A new repair depot was formed at the site, as was No. 1 Maintenance Wing and No. 101 RCAF Equipment Park. These units were short-lived however, as they disbanded on 1 November 1945. The RCAF departed and the aerodrome was abandoned. One thing for sure, this was a big installation with 6 large hangars and two smaller ones for repairing and modifying aircraft. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Long-term storage in Alberta

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan base at Pearce, Alberta. Opened by the Royal Air Force north of the Village of Pearce on 30 March 1942 as No. 36 Elementary Flying Training School, part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. The school had a brief existence as it closed on 14 August 1942. No. 3 Air Observer School of Regina, Saskatchewan opened a Detachment at the aerodrome on 12 September 1942. The school operated at the Pearce aerodrome until 6 June 1943 when both the Pearce and Regina schools closed. No. 2 Flying Instructors School, originally from Vulcan, relocated to Pearce on 3 May 1943. The school closed on 20 January 1945. Although the airfield was abandoned, the former school continued to be used as a storage depot and scrap yard. Many Second World War Lancasters and training aircraft met their final fate at the Pearce Depot. The Depot closed in 1960. Photo via Flight Ontario

The instructors, students and staff of No. 2 Flying Instructors School at Pearce, Alberta during the Second World War stand in front of one of the school’s Cessna Cranes and a Harvard. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A close-up of the previous photo reveals a happy crew at No. 2 Flying Instructor’s School. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Until the RCAF could figure out exactly what they were going to do with the Tiger Force Lancasters, they were flown in groups away from the wet and salty air of Scoudouc, an airfield not far from Northumberland Strait and moved to partially closed and former British Commonwealth Air Training Plan bases on the Alberta prairie—places like Fort McLeod, Medicine Hat, Vulcan and Pearce. This shot of flight students at the Pearce railway station during the Second World War tells you all you need to know about the remoteness of this tiny farming community. Pearce itself could not have been more than a few houses and grain elevators and today, largely because the highway no longer goes near it, it is a ghost town. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

The only known photograph of a Lancaster arriving at Pearce in 1945. Pearce was closed down and vacant by January of 1945, and then officially reopened on 7 September 1945 to accept incoming Tiger Force Lancasters. The very next afternoon, 83 Lancaster Mk 10 bombers arrived and landed at the old base. This shot was taken by Ray Wise, an RCAF mechanic who was tasked, along with a Corporal Edge, LAC Cook, and LAC Wyers, to take care of a large number of Lancaster aircraft which were soon to land... and land they did.

Ray Wise was 92 years of age when he was interviewed by Clarence Simonsen, Canada’s leading authority on nose art and Jim Blondeau, a documentary filmmaker with Dunrobin Castle Productions. Blondeau remembers, “... he still spoke with excitement about the spectacular arrival and low flying air show they witnessed at Pearce on that one single fall afternoon. Out in the middle of nowhere the ferry crew pilots showed their low level flying skills, terrifying nearby farm animals and the local Alberta farmers. Ray Wise also helped to record and save Canadian history when he took along his camera. His collection shows Anson ferry pilot aircraft, the rows of Lancaster bombers and most of all the Canadian Nose Art, painted on our most famous Lancaster aircraft. Just eighteen months after the photos were taken some of these aircraft were unceremoniously scrapped without any due thought by Canadian authorities.

Once the Lancaster bombers had arrived they were parked in long rows and each morning the four mechanics were ordered to start each of the four Merlin engines on all the 83 aircraft. Over the next six months ferry crews arrived at Pearce and the Lancaster aircraft were flown to various long-term storage areas in southern Alberta. The mechanics were also ordered to prepare as many bombers as the Pearce hangars could hold for long-term storage.” Photo by Ray Wise via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Once the Lancasters were on the ground, they had to be organized to fit as tightly as possible to save space, but still with adequate room around to work on them and start their engines daily. Here we see Ray Wise’s mates towing the bombers into position off the ramp. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A photo by Ray Wise, taken from the roof of one of Pearce’s hangars looking south, shortly after the arrival and parking of 83 Lancasters. It was Ray Wise’s duty, along with others, to keep them functional until their disposition could be decided. 83 Lancasters, 332 Merlins, and just a few mechanics... quite a daunting task. Because the hamlet of Pearce was so tiny, Ray and his mates rented a house in Fort McLeod and commuted daily. Photo by Ray Wise via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Looking down the flight line at Pearce in the autumn of 1945. We can see that the tires have been covered to reduce sun damage to the rubber. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Another photograph of the Pearce flight line and the former Tiger Force Lancasters looking southwest. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Some of the Pearce ground crew, tasked with the daily upkeep of the grounded Lancasters, stand on a scaffold next to a combat veteran Canadian Lancaster with 51 sorties—clearly on a warm day in the fall of 1945. Photo by Ray Wise via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Thanks to Ray Wise, we have today a fair record of the aircraft and even the staff who were tasked with the care of these old warhorses. Here some of Pearce’s airfield staff pose in front of Lancaster KB732, VR-X, the X-terminator. X-terminator boasts 83 combat bombing operations on her nose as well as two Luftwaffe fighters destroyed and there is no doubt she was the source of some extermination on the ground. It is very clear why these men (LAC Wyers, Corporal Edge and an unknown mechanic) wanted to be photographed by Wise in front of this particular Lancaster bomber, for the legendary X-terminator was the greatest of all Lancs in the RCAF—surviving more operations than any other. For a superb recounting by historian Dave Birrell of this aircraft’s remarkable combat history found on the Bomber Command Museum’s website, click here. Sadly, this greatest of all Lancasters was later ferried to Calgary for long-term storage, was struck off charge in May 1948 and scrapped for its value in metal. Photo by Ray Wise via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Another great shot by Ray Wise, of some of the same lads as in the previous photograph. Note the airfield dog sitting on the tarped port tire. It is interesting to note that the bomb doors seem to be open in most of these photographs. One would think that they would have been closed to keep birds from nesting in the bays, but the stress on the hydraulic system was reduced by dropping them open. As well, John Coleman says, “Since the engines were started daily, that they were left open on purpose. When we start our Lanc the bomb doors ALWAYS must be open. Early in the Lanc’s career they lost a few to massive explosions. It turns out that fuel vapours tend to collect in the bomb bay.” Many of the following photographs reveal that this was standard for storage. Photo by Ray Wise via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A few Lancs and an Anson at Pearce. Note bomb doors open on the Lancaster. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

We covered Lancaster KB839 D for Daisy earlier in this story, but here we see her at Pearce, with bomb doors agape, before she was modified to become a Maritime Patrol aircraft. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

After their stay at Pearce, many Lancasters were prepared to be scattered to other former BCATP bases across southern Alberta. Here we see KB881, called C for Chopper, which had been issued to 419 Moose Squadron in March of 1945 and given squadron code VR-C, being prepped for dispersal to the BCATP training field at Penhold near Red Deer, Alberta. According to records on the Bomber Command Museum website, Chopper returned to Canada on 2 May, a full four weeks before the first mass crossing of the Atlantic which was attended by Harris and McEwen. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A shot of Lady Orchid, a 434 Squadron Lancaster (KB895) at Pearce. Lady Orchid is one of the more interesting Lancs of Tiger Force. The Lanc rolled off the assembly line at the Victory plant in January of 1945 and flown immediately to England. It was originally issued to 428 Ghost Squadron RCAF, but in March of 1945, it was reissued to 434 Schooner Squadron. It completed 35 combat operations with aircraft code WL-O Oboe. After a brief period at Pearce, it was placed in storage at Penhold and struck off charge in January 1947. The nose art on the port side originally featured a totally nude blonde gal straddling a massive bomb as she holds 2 pistols with the red and white script “Lady Orchid” below the nose art. For her journey home, her sexy bits were covered up with red maple leaves. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

The nose art of Lady Orchid was immortalized on another Canadian-built Lancaster (FM136), at the Aero Space Museum of Calgary, Canada, chosen no doubt because its crew commander hailed from Calgary. The story behind Lady Orchid is fascinating. Its 434 Squadron pilot, Ron Jenkins of Calgary, Alberta was allotted KB895, coded WL-O as “his” and permitted to name her. He and his crew chose Wee Lady Orchid for each of its WL-O code letters. The entire crew had a hand in the painting. The six guns were a nod to Jenkins’ home in Calgary, Alberta. Eventually, they dropped the “Wee” suffix. Five of Jenkins’ 15 combat sorties were in Lady Orchid and under his pilot position he painted fifteen white bombs and one red bomb for an aborted operation—this was likely done at the same time the maple leaves were added over Lady Orchid’s breasts as they are not the normal way someone would systematically add his combat ops marks. Lady Orchid crossed the Atlantic and landed in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia on 17 June. When she was struck off charge, Jenkins, who had done well in the family grocery business, purchased the Lancaster and had the seats and equipment from each crew position stripped from the hulk and sent to the corresponding member of his old crew as mementos of their service together. He then gave the airframe back to War Assets, who then sold it to a farmer who was going to use it as a machine shop and storage shed. Years later, when an RCAF Lancaster stalled and crashed at Greenwood, Nova Scotia, it was deemed repairable if a replacement centre section could be found. By this time all the Lancs had been scrapped, but someone remembered the Lady Orchid airframe that belonged to the farmer, who, as it turned out, had done nothing with his Lancaster. He was willing to sell it back to the RCAF, which sent the largest flatbed railcar in Canada all the way to Alberta from New Brunswick to collect the centre section which had been removed from the old airframe of Lady Orchid. That centre section was mated with the wrecked Greenwood aircraft at Downsview, Ontario and enabled Lancaster FM213 to be put back on the flight line in 1953. It continued to fly for an additional ten years at 107 Composite Unit at Torbay, Newfoundland. THAT Lancaster, with the centre section of Lady Orchid, is still flying today with the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum, one of only two flying Lancasters remaining of the 7,377 built during the Second World War—an aircraft that pays homage to a 419 Squadron RCAF air gunner by the name of Andrew Mynarski, a Canadian Victoria Cross recipient. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

One of the old BCATP training airfields designated as an aircraft storage facility was at Claresholm. Here we see some of the dispersed Lancasters awaiting their fates on the grass at Claresholm in 1946. By the style of lettering on their sides and the snowy owl painted on their vertical stabilizers, the first two on the right row are from 420 Snowy Owl Squadron. The Lanc in the foreground, PT-G (KB937) was too late for combat, being assigned in April of 1945 to 420. It returned to Canada on 14 June of that year. Though never having been in combat in the Second World War, KB937 was selected for conversion to Mk10MP (Maritime Patrol) standard shortly after this photo was taken and served as an OTU conversion aircraft at RCAF Station Greenwood, Nova Scotia until it was struck from the lists in June of 1960. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Lancaster KB860, L for Lanky was coded VR-L with 419 Moose Squadron, RCAF. She arrived in England in November of 1944, but was not assigned to 419 Squadron until February 1945—she still had enough time left in the war to put 18 ops under her belt. She was stored first at Pearce, and then flown to Medicine Hat, Alberta to make room for other aircraft being processed at Pearce. By January of 1948, she had been struck off charge and scrapped. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

The Lancaster ground maintenance crew at Fort McLeod, Alberta. McLeod was one of the former BCATP airfields where the Lancasters were dispersed, and though its first resident unit, No. 7 Service Flying Training School, had shut down in November of 1944, it housed No. 1 Repair Equipment and Maintenance Unit after the war, and a slew of Lancasters awaiting their fates. This greasy, but happy crew were tasked with upkeep of the Lancs stored at Fort McLeod. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A couple of RCAF mechanics pose in a relaxed manner on the port outer Merlin of Lancaster Piddlin’ Peter. While trying to identify the serial numbers and squadron codes associated with a Lancaster with that sobriquet, it became clear that there were two Piddlin’ Peter Lancasters, one with 431 Squadron and one with 419 Squadron. The records that I was able to find seemed to indicate that the 419 Lanc remained in England and was scrapped there. The 431 Lancaster (KB773) was listed as SE-A on the BCMC website, but further investigation revealed that KB773 was indeed SE-P, Piddlin’ Peter. Flying Officer Bill Dowbiggin flew Piddlin’ Peter from RAF Croft, Yorkshire to Dartmouth, Nova Scotia via Cornwall, Azores and Gander, landing in Canada on 14 June 1945. Dowbiggin had flown Piddlin’ Peter on 13 of its more than 30 combat ops. The aircraft was stored at Vulcan, Alberta and scrapped in 1948. One of its main gear tires is still on display at the Bomber Command Museum of Canada.

By the winter of 1945–46, there was a lot more aircraft in storage at Pearce and other airfields throughout Alberta than the remaining Lancasters, including this massive array of Avro Ansons, now no longer needed for pilot, bomb aimer and navigator training with the BCATP. The Anson closest to the camera, 8249, was used by the Bombing and Gunnery School at Lethbridge, Alberta during the war. It had a total of 2,001.25 hours on the airframe and had never been overhauled. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

From sword to plowshare. Depending on how you look at the photo, it is either amusing or terribly sad. Here, in the summer of 1948, we see two farm tractors pulling the 434 Squadron Lancaster Dauntless Donald (KB830/WL-D) like a shot moose across the dusty prairie to its new life on a farm—the price was only $250.00. Farmers bought surplus aircraft like Dauntless Donald for the fuel and glycol still on board or to make implement and storage sheds from their fuselages. In addition, there were hydraulic, sheet aluminium and wire components that a resourceful farmer could make use of. While the fate of this lovely aircraft may break our hearts, one must remember that after the war, there was only a few ways to deal with the literally hundreds of thousands of surplus aircraft—store them, cut them up or sell them to whoever wanted them. Today, throughout Canada, the US and England, it is often the farmer’s chicken house, implement shed or water trough that is the source of rare components for warbird restoration. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

In 1948, Alberta rancher Victor Leonhardt poses on the running board of his farm stake truck before towing his new Lancaster back to his farm from Penhold. It appears he has also purchased a Lancaster tail wheel tow bar as well. Leonhardt bought this 420 Snowy Owl Squadron Lancaster (KB941) for $350.00, as well as Lancaster KB994. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A close-up of rancher Leonhardt about to drag away his new Lancaster KB941. The only flying time accumulated on Lancaster PT-U was its factory test, two transatlantic crossings and the cross-Canada flight. I suspect this would be less than 100 hours. Leonhardt was a two-Lanc man, having also purchased KB994. The Bomber Command Museum’s listing of the fates of all Canadian Lancasters tells us of the fate of that second Leonhardt Lancaster below:

“An advertisement in his local paper drew the attention of Drumheller area farmer Victor Leonhardt who read that the Canadian Government War Assets Corporation was selling Lancaster Bombers at Penhold, Alberta. Victor drove to Penhold, placed a bid of $350 and returned home the owner of a World War II bomber. He made plans to tow the aircraft along the ice of the Red Deer River to his farm near Drumheller. This idea and the ice proved to be somewhat unstable, so KB994 was taken apart and trucked to Drumheller.

In 1963, Leonhardt sold his farm and moved to Pigeon Lake, Alberta, towing his Lancaster behind him. A decade later, and after having used many of the parts of the aircraft for other purposes, Leonhardt sold the aircraft to Neil Menzies of St. Albert, Alberta for $1,500. Over the next ten years, Menzies searched for missing parts, locating two engines in Drumheller and two wings in Le Pas, Manitoba. Soon the price of the bomber began to rise as people from all over the world sought to buy the aircraft. Menzies turned down all offers until 1984.

A very compelling photograph, taken in 1973, of KB994, one of Vic Leonhardt’s two Lancasters, purchased in almost perfect condition at Penhold in 1948. Both aircraft had been trucked to Drumheller in 1948 and had largely been picked over for usable parts but, in the 1960s, when he chose to move to Pigeon Lake, some 150 miles away, the family could not part with the remains of the Lancasters and they were brought to their new home west of Wetskawin. Photo by Dick Richardson via timefadesaway.co.uk

During July 1984, No. 408 Squadron, which had become a tactical helicopter squadron and was based at CFB Namao in Edmonton, held a reunion that was attended by over four hundred veterans. Under the leadership of Lt. Col. Murray Lee, a project had been started to acquire and restore a Lancaster in the markings of No. 408 Squadron. Neil Menzies had donated the fuselage of KB994 to the squadron, together with all the additional parts he had acquired. On 27 July 1984, over four hundred men of No. 408 Squadron drank a toast next to the wingless, dilapidated KB994. One of the veterans was ex W/C N.W. Timmerman, who was first given command of the squadron at Lindholme, Yorkshire, England in June 1941 and the man who gave the squadron the name “Goose” and the motto “For Freedom.”

Another wonderful photograph of Lancaster KB994, overgrown by brush at the Leonhardt farm at Pigeon Lake, Alberta. Only the fuselage remains, with its traditional short Lanc nose having been removed and been donated to Lancaster KB976, being restored by 408 Squadron in Comox. Photo by Dave Welch via timefadesaway.co.uk

A close-up of the fuselage of KB994 as it rested in the Leonhardt wood lot at Pigeon Lake, Alberta. Though a quarter century had passed since Vic Leonhardt towed it away from Penhold, the paint is still mostly there, but vandalized by no less than Elvis Presley and Twiggy! Photographer Dave Welch, a Martinair DC-8 navigator, was on a four-day layover in Edmonton when he drove to photograph this aircraft in August of 1973. Photo by Dave Welch via timefadesaway.co.uk

Unfortunately the next commanding officer that took over No. 408 Squadron lacked the enthusiasm for the project that Lt. Col. Lee had demonstrated and according to one ex-408 member, “strictly forbade” any effort towards the project. The fuselage, bomb-bay doors, and other parts languished around No. 408’s hangar for a time until the late 1980’s when the aircraft was returned to Neil Menzies.

The fuselage of KB994 was airlifted from Pigeon Lake, slung beneath a Canadian Forces Chinook helicopter. Its fuselage was mated with the long Maritime Patrol nose of KB976 (though they had the short nose of KB994 already) as part of an aborted attempt by members of 408 Squadron to build a commemorative Lancaster for their museum. Photo via Dick Richardson and timefadesaway.co.uk

Mr. Menzies subsequently sold the aircraft to Charles Church, a private collector in England who was planning to make use of it in conjunction with Lancaster KB976 which he had previously acquired. Most of what remained of KB994 was shipped to England. For some reason the two bomb-bay doors remained. Later they were donated to the Calgary Aero Space Museum for the restoration of their Lancaster FM136.

Tragically, Charles Church was killed while flying a Spitfire. His Lancaster collection went though a few different hands before it was purchased by Kermit Weeks of the USA and parts of both aircraft are currently stored in large containers at Kermit’s “Fantasy of Flight” in Florida.”

The 408 Squadron rebuild of a Lancaster using the fuselage of KB994 was abandoned when a new commanding officer did not grasp the importance of the project and returned the fuselage to Neil Menzies, who in turn sold it to Charles Church of England for a restoration project. This is a photograph of the fuselage arriving to RAF Bruntingthorpe back in the late 1980s. Today, this fuselage rests in Kissimmee, Florida. Photo by Dick Richardson

When researching this story, I was fully convinced that Lancaster KB976 had ended up in Kissimmee, Florida with Kermit Weeks. One of our long-time readers and international aviation consultant Mike Pearson set me straight on that with this astonishingly timely photograph he had taken... JUST YESTERDAY! Mike writes: “By total coincidence, I’ve woken up to your article in my inbox, only a day after I had taken my son to the Brooklands Air Museum, in south-west London (not far from Heathrow). The attached photo is taken from the top of an elderly double-decker bus that was doing rides around the site. I snapped the photo rather quickly as we drove past because the red/white markings drew my attention. Although it is part-covered in tarp, protecting it from the deluge of rain we’ve experienced in recent weeks, the forward fuselage (nose only) is of KB976! ...the very same aircraft that is shown at the end of your article! An unbelievable coincidence, for me anyway, given your article’s timing! How did that flying beauty end up with just its nose section back in the UK? Do you happen to have any research on that aircraft?” The static test fuselage of the TSR-2 lies in the background. For Canadians, this aircraft had, in many ways, similar development promise and sad ending as our beloved Avro Arrow. Reader Andrew Hilton has told us (September 12, 2014) that the nose and the newly built fuselage it is attached to have been moved to RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire. Photo: Mike Pearson

Once a warhorse, now sharing the farmyard of an Albertan rancher with his cows and horses, this Lancaster looks truly out of place. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Not all Lancasters disappeared into oblivion on the sweeping prairie landscape or were dragged to ignominy by ranchers. Many of the Lancasters went on to relatively long and illustrious careers as Photographic, Maritime Patrol or Area Recce aircraft with the RCAF, designated Mk10P, Mk10MP or Mk10AR, respectively. Here, in 1953, we see ten mechanics swarming a Lancaster at Fort McLeod prepping it for delivery to Calgary where it will undergo conversion to the Mk10MP standard—the very last to be converted. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A close-up of the previous photograph shows us that the Lancaster is in pristine condition (considering that it had been in storage for eight years) and sports a new lightning bolt cheat line running the length of the fuselage. The lightning bolt motif would become an RCAF design standard throughout the next four decades. We see that the defensive guns have been removed. Many Maritime Patrol Lancasters would receive an extension forward of the cockpit which would give them a leaner look (see previous photograph of the Lancaster at the Greenwood Military Aviation Museum). Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

One of the lucky Pearce Lancasters to receive a second chance to defend her country was FM159. Probably one of the last Lancasters to be flown to England, it arrived there in May 1945, being stored at No. 32 Maintenance Unit awaiting turret installation and assignment to a squadron. It was returned to Canada in September of 1945 and eventually modified to Mk10-MP standard, serving with 407 Squadron and 103 Rescue Unit as RX159. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Lancaster FM159 would become RX159 in its Maritime Patrol configuration. Here we see it on exercises in Alaska taxiing past other Lancs of 407 Squadron. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Lancaster FM159 was one of the lucky aircraft to have been converted to a Mk10-MP. It was moved from Pearce to Fort McLeod in March 1946. Then, in the early 1950s, it was one of 70 stored Lancasters to be given a new lease on life. It served with the legendary 103 Search and Rescue Unit at Greenwood, Nova Scotia until early 1955, when it got some newer anti-submarine warfare upgrades and was transferred to RCAF Station Comox with 407 Squadron. With 407 Squadron it served from Alaska to Great Britain and everywhere in between. The Bomber Command Museum website tells the story of its final flight: “The Lancaster era at Comox drew to a close in 1958 and it was with some nostalgia that F/L Brooks and flight engineer Duke Dawe left Comox, flew across the mountains, and parked FM159 at RCAF Station Calgary. The aircraft had acquired a total of 2,068 hours since its overhaul in 1953. Duke recalled that leaving Lanc159 was a “rather moving experience.” He had flown in the aircraft 62 times, accumulating a total of 224.5 hours and he “always had a very great feeling for her.” Later, a civilian crew flew the aircraft to the former BCATP base southwest of Vulcan where its engines and props were removed and the aircraft was to be scrapped.”

Luckily, scrapping was not to be! In 1960, Nanton, Alberta resident George White was looking to acquire an aircraft for his community to use as a war memorial and tourist attraction. When he learned that FM159 was to be broken up for scrap at nearby BCATP base at Vulcan, he and two others pulled together the $513.00 necessary to acquire the airframe. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Volunteers from the community of Nanton waited until the harvest of wheat was in before they hooked up Lancaster FM159 (RX159) and towed her across the prairie from Vulcan to Nanton, a distance of some 35 kilometres as the Lanc flies. Here we see the tow vehicle and the Lancaster fording the Little Bow River, about halfway to Nanton. We can see that the engines have been removed and the RCAF markings have been painted over. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Readying FM159 for the tow at Vulcan

FM159, the “Nanton Lancaster” would spend five decades in various states of repair and disrepair at an intersection in the small town in Alberta. Here we see it in 1972 as the Bull Moose and in pretty poor condition. The original reason to bring the Lanc to Nanton was to create a tourist attraction. In doing so, it became the nucleus of a group of dedicated men and women who did, in fact, create a more important and longer lasting tourist attraction in Nanton—the Bomber Command Museum of Canada. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

The long, long story of the Nanton Lancaster is one of a community dedicated to preserving the history of military aviation in Alberta and bringing back to life a vintage bomber that was just days away from the scrapper’s saw. In the summer of 2013, the Bomber Command Museum of Canada, the final owner of FM159, the Nanton Lancaster, reached the penultimate milestone—the running of all four Merlins... at night and in front of hundreds of admirers. Though it will never fly again, the hearts and minds of Nanton and Alberta citizens were flying this night! Photo: Bomber Command Museum of Canada; Doug Bowman

No story about the Canadian-built Lancasters would be complete without FM213. FM213 was not one of the Tiger Force Lancs nor was it stored in Alberta, but rather RCAF Station Trenton, Ontario as she did not make it to England at the end of the war. She is, however, the most successful of all the Canadian Lancs, as she is still flying today as the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum’s Mynarski Lancaster, one of only two Lancs flying in the world and the only Canadian-built example. But it was not a life of continuous flying. FM213 was selected for conversion to Maritime Patrol and as such served with distinction with both 405 Squadron at Greenwood, Nova Scotia and 107 Rescue Unit at Torbay, Newfoundland. Photo via Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum

After her flying service, FM213 stood as a memorial at Goderich, Ontario on the shores of Lake Huron. She was depicted “wheels in the wells” in level flight. One can almost feel the thunder of a low-level pass. Photo via Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum

The Legion at Goderich raised funds to have FM213 raised up on three posts and there was a substantial dedication ceremony when the work was completed. During the Second World War, Goderich, a salt mining and Great Lakes harbour town was host to a BCATP training facility—No. 12 Elementary Flying School. Photo via Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum

FM213, stripped of wings, engines and extra weight, ready for airlifting from Goderich airport to Hamilton by 450 Squadron Chinook. The museum’s volunteers had a heavy task ahead of them to restore their new acquisition to flying status, but it was one they were eager to take on and still help to maintain her today. Photo via Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum

FM213 at Hamilton shortly after her delivery by air. Even without wings or engines, the aircraft stands magnificently. Photo via Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum

With work towards a flying Lancaster in Canada well on the way, the FM213 project is rolled out for all to see at an air show at Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum in 1985. Photo via Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum

The nearly completed Lancaster at the 1988 Hamilton International Air Show. One sees just how elegant the Avro Lancaster is when displayed in bare metal. Photo via Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum

The Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum’s fully restored Mynarski Lancaster is escorted by two CF-5 Freedom Fighters, the nearer of the two being the 419 Moose Squadron’s air show bird (now, like the Lancaster had once been, it is retired and on a pedestal in Kamloops). The Lancaster was painted in the markings of 419 squadron, so the escort is extra special. Photo: RCAF

There is no shortage of aircraft that would love to be photographed side by side with the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum’s Lancaster. Here, Vintage Wings of Canada’s Hawk One Sabre in Golden Hawks markings slows down to hang with the big bomber. Photo: Peter Handley, Vintage Wings of Canada

Earlier in this story we had mentioned that 83 Avro Lancasters arrived at Pearce, Alberta at the same time and many were loath to land. Instead, these Lancasters spent the last of their fuel low-level flying over the prairie, the air crew squeezing the last ounces of joy out of their venerable bombers. Here, in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, on that same prairie, some 65 years later, the CWHM Lancaster shows us how joyful that must have been. Photo from Saskatoon Tower

Also taken from the Saskatoon Airport’s control tower, we see just how low this Lancaster was. One thing of note here is the dihedral of the wings. On the blue circular nose art, we see a depiction of a Victoria Cross, the medal awarded to Andrew Mynarski. Mynarski was 27 years old and flew with 419 “Moose” Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force during the Second World War when he gave his life attempting to help rescue a trapped crew member. His Victoria Cross was awarded in 1946 as the last such award to a Canadian airman in the Second World War. Photo from Saskatoon Tower

The CWHM Lancaster is an annual visitor to Vintage Wings of Canada on Battle of Britain Day, where she pays tribute to the more than 10,000 airmen lost on operations with Bomber Command. Photo by Colin Huggard

Boneyard of Derelicts

Lancasters at Pearce in the final days, with collectors and mechanics picking over the bones. The 70 or more which were selected for Cold War patrol were the lucky ones... but just for a few years more. This is the sad end of many of the Canadian Lancasters... rotting and crumbling, being picked over, shat on by pigeons, fading under the prairie sun. Canada’s leading aviation historian and publisher summed it up perfectly: “Barnyard bombers were well worth the fifty dollars asking price. To begin with, a farmer could count on recouping his investment by simply draining gas and antifreeze from his plane. Tires were just fine for a farm wagon. A tailwheel fit the wheelbarrow. For years to come the carcass would be a veritable hardware store of nuts and bolts, piping and wiring. In the meantime it made a suitable chicken coop or storage shed. One farmer converted the nose of his Anson into a snowmobile.” Photo via Larry Milberry, Aviation in Canada, Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Ltd., 1979

The last crumbling Lancs out at Pearce, with their engines removed—sometime between 1950 and 1955. Canada still operated Merlin-powered Mustangs in reserve squadrons plus Merlin-powered North Star transports, so the engines were still valuable and usable. The Pearce Lancasters became somewhat of a tourist attraction in themselves. Here, members of the Szoke family roam the Pearce storage area and pose with one of the engineless Lancs. Photo via Szoke Family

The Lancasters begin their long fade to oblivion—1950–55. Photo via Szoke Family

All their engines removed, these dozens of crumbling Lancasters have been scavenged, cannibalized and vandalized at Pearce with no one to protect them. Photo via Palsky Family

Visitors were clearly free to climb over these derelict historic artifacts as they sank into the ground. For a vintage aircraft lover, this is the worst of all endings, but the finest of all places to walk. Photo via Palsky Family

Looking at this photo of the last Lancs at Pearce, there is nothing more to say. Photo via Palsky Family

Earlier, we saw the nose art and learned about the history of 428 Squadron’s NA-S Sugar’s Blues. This is how she was found by the Szoke family in the mid-1950s—engines removed, rubber rotted, bomb doors gone and all cockpit glass shattered. Photo via Szoke Family

The tragic end of a war machine—covered in bird shite, broken, vandalized—all in less than ten years. Hopefully these young members of the Szoke family understood the history they had climbed into and felt the ghosts of the 10 thousand Canadian boys who died in Lancasters, Halifaxes, Wellingtons and others. Thanks as well to this family for sharing these final moments with these legendary aircraft. Photo via Szoke Family

Just so our readers don’t think it was dereliction and ignominy for all the Canadian Tiger Force Lancasters, I leave you with this beautiful photo of one of those Lancasters—KB976, flying over Canada somewhere. These old warhorses went to work and did journeyman service patrolling our coasts, reconnoitering the icebergs coming down from Greenland, and photographing and mapping our great country. In this image we can clearly see the extended nose of the MP-configured Lancasters of the RCAF. For a Canadian boy who grew up near RCAF Station Rockcliffe, this was a common sight. A silver-bellied, white-backed thunderer roaring across the skies as seen through my binoculars. Perhaps, at least for that young boy, this was, and still is, the most beautiful iteration of the Lancaster—a true Tiger Force. RCAF Photo via Dick Richardson and timefadesaway.co.uk

![Another Lancaster by the name of Hell Razor sits on the Scoudouc storage line. Its nose art shows a bat-winged creature with a jagged straight razor for a beak and a machine gun spitting bullets from its mouth whilst dropping bombs from its clawed feet. The Bomber Command Museum website has a powerful story about Hell Razor: Lancaster Mk. X KB885 was built at the Victory Aircraft Plant at Malton, Ontario and ferried to a maintenance unit in England. It was assigned to No. 434 [Bluenose] Squadron in March 1945 and the markings WL-Q were painted on the fuselage. The number of operations flown by KB885 with No. 434 Squadron and their details is not known. In April 1945, the aircraft was transferred to No. 420 [Snowy Owl] Squadron based at Tholthorpe, Yorkshire, England. Here the aircraft was assigned the code letters PT-Y.However the war in Europe ended before KB885 could fly combat operations with its new squadron. No. 420 Squadron returned to Canada on 14 June 1945, and prepared for duty in the Pacific as part of “Tiger-Force.” The dropping of the two atomic bombs and the total surrender of Japan ended the Second World War on 15 August 1945. No. 420 Squadron was disbanded at Debert, Nova Scotia on 5 September 1945.On 8 September 1945, KB885 arrived at Pearce, Alberta together with 82 other Canadian-built Lancaster veterans. In the next three months all these aircraft were flown to different RCAF bases in Alberta and placed into long-term storage. KB885 was flown to what was formerly #37 Service Flying Training School in Calgary and placed in a hangar. In 1947, the Canadian Government decided to sell a number of Lancasters. The RCAF struck KB885 off strength and sold it to C.R. “Charlie” Parker of Red Deer, Alberta for $275.00. The aircraft was flown to Penhold (formerly the site of #36 SFTS under the BCATP), where she appeared at an open house air show on 11–12 June.Health reasons forced Charlie Parker to sell “Bomber Service” in 1954. Two years later, the business was purchased by Walter Mielke. Mr. Mielke was approached by Troutdale Airmotive Company of Troutdale, Oregon, who offered to purchase the Lancaster for $6,000 and convert it into a fire-fighting water bomber. The offer was accepted on the condition that Troutdale purchase a surplus P-40 Kittyhawk from the RCAF base at Vulcan and move it to “Bomber Service” to replace the LancasterPreparations then began to make the Lancaster airworthy and ferry KB885 to California for licensing and then to Portland, Oregon to be modified to become a water bomber. The cost to prepare the aircraft for flight was estimated to be $14,000. James Sproat, a Portland pilot who was to fly the aircraft to California, was reported as saying that the bomber was to carry 4,000 gallons of water and would be able to lay a 200-foot swath of water one inch deep in the path of an advancing fire.The weather was good in the fall of 1956 as two air force mechanics from the Penhold base assisted with preparing KB885 for flight. New Rolls-Royce Merlin engines were fitted and run-up, the elevators, ailerons, and rudders were refurbished, new tires were installed, and a makeshift runway was bulldozed in a nearby field.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1628601141124-58RH4CIFBA6R7TEPH0KZ/LastCall17.jpg)