The Memory That Would Not Die

It was raining heavily with high gusting winds at RAF St. Eval, late in the morning of June 20, 1943 when two aging, white-painted Armstrong Whitworth Whitley Mk VII bombers laboured into the sky, climbed out over the choppy, wind-slashed Celtic Sea and turned southeast across the thick neck of the Cornish peninsula towards the Bay of Biscay. It wasn't a pleasant day, that's for sure, but for training Coastal Command anti-submarine crews, it was about as realistic as it got. Both Whitleys were part of a small anti-submarine detachment from No. 10 Operational Training Unit (OTU) at RAF Abingdon near Oxford and were engaged in training pilots and novice crews for the difficult, mostly boring, sometimes harrowing job of searching for and destroying enemy submarines.

As they crossed the Cornish countryside, they levelled off beneath the overcast and bucked their way through intermittent rain squalls and broken shredded cloud with that strange nose-down attitude unique to the Whitley. Beneath them lay the lush green quilt of Cornish farm country, dark moors and granite outcrops common to Cornwall. Somewhere to the northeast of Falmouth they crossed the south coast of England, turned southwest across the wide mouth of the English Channel and entered the enormity of the Bay of Biscay—225,000 square kilometres of cold, grey-blue seas whipped by the wind and beneath which thrummed the silent electric passage of U-boats making for or leaving the big submarine pens of the French Coast—La Rochelle, Lorient, St. Nazaire, Brest and Bordeaux. Though all U-boats travelled as much as possible underwater while transiting the Bay of Biscay, none of them had the battery power to make it all the way. The Royal Air Force's Coastal Command brass and the mathematics and statistics boffins knew that if they could keep constant and widespread vigil over the bay, night and day, catching submarines on the surface was inevitable.

The Whitley was originally designed without flaps, and a high angle-of-attack wing was used to get the aircraft into the air and back on the ground. Later it would be fitted with flaps, but the high incidence wing remained. In cruise, however, it flew with a very distinctive nose down and drag-producing attitude that gave it the appearance of always being in a shallow dive. Photos: RAF

The Roll Royce Merlin-powered Whitleys of No. 10 OTU were not long from retirement and the crews who manned them were both in training and on operations at the same time. Whitleys, along with Handley Page Hampdens and Vickers Wellingtons played the central strategic bombing roles in Bomber Command as well as with Coastal Command at the outset of the war, even though they were not designed for that purpose. But larger bombers such as Avro Lancasters, Handley Page Halifaxes and Short Stirlings had rendered the Whitley obsolete, relegated to training roles in northern Europe. Part of the No. 10 OTU's mandate was to transition newly winged aircrew from Great Britain and the Commonwealth countries into fully combat-ready crews. Crews were a blend of seasoned airmen and as yet-to-be-tested specialists—pilots, bomb-aimers, navigators, radio and radar operators and gunners. By the time they finished at the operational training school, crews would have operational experience that would allow them to proceed to a Heavy Conversion Unit where they would transition to Coastal Command's new core aircraft such as the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, Short Sunderland and Vickers Warwick. A Whitley crew was normally comprised of five men—a pilot, co-pilot/navigator, bomb aimer, radio operator and rear gunner. However, these particular Whitleys were designed for anti-submarine operations and carried a sixth man to operate the ASV Mk2 Radar equipment.

A Whitley Mk VII of Coastal Command showing the radar mast installation on its top side. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Three members of a typical five- or six-man Whitley crew work in the very tight confines of the cockpit in this RAF promotional shot. At right is the pilot in command, while left, the second pilot who also was required to handle navigation, confers with the radio operator. The role of pilot/navigator on Whitley EL-L was filled by Flying Officer Clifford Mervyn Bingham of Winnipeg, Manitoba. Photo: Imperial War Museum

A view of a Whitley cockpit. The empty seat at right is for the pilot/navigator who did the navigational work and relieved the pilot-in-command on long anti-submarine patrols. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The two-aircraft section was led by Pilot Officer Orr who was flying Whitley EL-J and his wingman was Flight Sergeant Harry Martin of Great Britain in command of Whitley EL-L (EL was the 10 OTU Squadron code worn in large letters on her sides). In Martin's Whitley were two Royal Canadian Air Force airmen—Flying Officer Clifford Mervyn Bingham of Winnipeg, Manitoba, a pilot/navigator and Pilot Officer Archibald Bertram Charles Durnell of Windsor, who was also a Navigator.

Orr led them throughout the day in a specified search pattern over a sector of the Bay of Biscay that had been assigned to them during their pre-flight briefing. About five hours into their long-ranging patrol while on a southerly heading, the radar operator in Orr's EL-J announced he had a target on his screen some 10 miles ahead, moving east to west—likely a U-boat on the surface. Orr radioed Martin and they went immediately into action. There was no sun to hide their approach, but Orr pressed on peering out through the windscreen until he could confirm it was a submarine. Orr led Martin in a shallow dive from their patrol altitude to just a couple of hundred feet above the water and took a bead on the submarine low in the water ahead.

One can only imagine the stress U-boat crews underwent hoping to sneak across the Bay of Biscay undetected. Lookouts were always searching the skies on all quarters hoping to spot enemy aircraft approaching. The submarine, now only a mile ahead of Orr and Martin, was most likely the Italian Marcello-class submarine Royal Submarine (R. Smg.) Barbarigo, out of Bordeaux and making for the open ocean. It's likely she did not spot them in time to submerge, or perhaps she had a mechanical issue that prevented her from diving, as her crew stayed to fight it out on the surface.

Barbarigo, commanded by Tenente di Vascello Umberto De Julio, was no longer an attack submarine, having recently been converted to an underwater freighter to carry valuable materiel between Germany and Japan. Her deck guns, torpedoes and her attack periscope had been removed. She had only defensive anti-aircraft guns still mounted. She had left Bordeaux on the 16th, loaded with 130 tons of high-value war materiel cargo, bound for Japan, with plans to return with a cargo of rubber and tin.

The Italian Marcello-Class submarine Barbarigo with crew turned out for a photo op from a warship keeping station alongside. Photo: WeaponsandWarfare.com

A poor photo Barbarigo's crowded conning tower as she comes home after a cruise. The graffiti on the side says: “Chi teme la morte, non e degno di vivere” which means “Those who fear death, are not worthy of living.” She completed 14 war cruises and was the fifth-highest scoring Italian submarine of the Second World War, but her life was not without controversy. Her first two Mediterranean sorties were without results, after which she was moved to the German submarine base at Bordeaux. Over the next months she carried out three more offensive cruises in the waters around Ireland, which netted her only one merchantman slightly damaged. In October of 1941, under command of Capitano di Corvetto Enzo Grossi, Barbarigo found a lone lighted ship — the Spanish SS Navemar — which was a recognized sign of neutrality. Grossi torpedoed and sank her anyway. The spring of 1942 found her in Brazilian waters where she attempted to attack a merchantman, but was caught and harried for five days by Brazilian B-25s and surface ships. She managed an escape and on May 20, found the cruiser USS Milwaukee and the destroyer USS Moffett on the surface. Grossi fired two torpedoes at Milwaukee (which he wrongly claimed was a Maryland-class battleship) and then claimed to have seen the explosions and heard the sounds of her sinking. Oddly, Milwaukee and Moffett were unaware of the attack and in fact both survived the war. It's hard to understand how a 7,000 ton four-stack light cruiser could be mistaken for a 32,000-ton behemoth like Maryland, but Grossi received plenty of chest pumping press, a promotion and the Medaglia d'oro al vala militare (Gold Medal of Military Valour). Five months later, off the coast of Africa, Grossi came across the corvette HMS Petunia on the night of October 6. He fired four torpedoes at her, then claimed it was a Mississippi-class battleship and that he had sunk it. Both Mississippi-class battleships (Mississippi and Idaho) and been sold to the Greeks in 1914 as Kilkis and Limnos. Both were training ships at anchor in a Greek port when they were sunk by German bombers a year before Grossi claimed to have sunk one. He was promoted again and given another Medaglia d'oro al vala militare. Petunia escaped unharmed and also survived the war. Two post-war enquiries stripped Grossi of his promotions and medals, but stated he acted in good faith. Photo: sixtant.net

Pilot Officer Orr in EL-J made the first bombing run, but all his depth charges exploded short of the target instead of straddling the submarine. However, as he flashed over the running Barbarigo, his rear gunner lashed the conning tower with his quadruple Browning .303 machine guns. As Orr pulled up and away, Harry Martin in EL-L made his approach on the target. As he drove to the target, Barbarigo slewed 90 degrees to the left, coming stern-on to Martin's Whitley. Orr was now circling the battle scene below—white foaming circles marking his own missed depth charge explosions and the churning wake of Barbarigo. He could see Martin's depth charges falling and splashing and then exploding well short of the target. From his cockpit he could not see any defensive fire from the submarine, but there is no doubt she was shooting. After Martin passed over the entire length of the submarine, Orr witnessed smoke and flames pouring from one of her engines and then watched as moments later, Martin, who may have been killed in the attack, lost control of Whitley EL-L and crashed into the sea with all six crew members killed — Flight Sergeant Harry Martin, Pilot; Flying Officer Clifford Bingham, RCAF, Second Pilot/Navigator, Pilot Officer Archie Durnell, RCAF, Navigator; Sergeant Walter Ettle, RAFVR of Somerset; Pilot Officer Frederick Tomlins, RAFVR of London, England; and Sergeant Robert Warhurst, RAFVR, of Derbyshire, England.

In a similar surface attack, a Royal Air Force Whitley of 77 Squadron drops depth charges on U-705 in the Bay of Biscay in 1942. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Within moments, the wake of Barbarigo thinned and disappeared as she submerged beneath the sea. With nothing left to do, Orr and his shocked crew turned for home. It was not certain whether any damage was made to Barbarigo, but she too was never seen again, along with her entire crew and three passengers. The Italian submarine base at Bordeaux, known as BETASOM, lost contact with her at this time, and never regained it. All that was left of Whitley EL-L and the six young men who were aboard her was some fuel on the surface and a few bits of debris. The Bay of Biscay, instantly and without malice, folded them into her cold embrace and sealed shut the stories of their lives. In the multi-continental cataclysm that was the Second World War, the deaths of these six men were just another barely audible click of the odometer of suffering. That journey towards peace would last two more years and the memories of these men were lost like a child’s cry in a hurricane. Somewhere thousands of feet below, the shattered wreckage of their lives would shortly settle on the bottom of the Bay of Biscay where it remains to this day.

The loss of the crew of Whitley EL-L would be felt immediately by the St. Eval detachment from No. 10 OTU, but the truth was that these men had not had much time to develop friendships with other airmen of the unit. A pint of beer would be raised in the Officers' and Sergeants' messes that night, or perhaps at subdued snug at the local pub, but a replacement crew and Whitley would soon arrive to fill the gap. Bingham's father, Lieutenant Colonel William John “Jack” Bingham, MC and Bar, VD (Veterans Decoration or Colonial Auxiliary Forces Officers' Decoration—an earlier long service award replaced now by the CD or Canadian Forces' Decoration), second in command of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, a Canadian infantry regiment that was training in England for the eventual invasion of mainland Europe, made his way to RAF St. Eval to speak with the 10 OTU commander about his missing son and to retrieve his personal effects.

At the same time, after confirming the loss of Bingham and Durnell, two telegrams would be composed at RCAF headquarters in Ottawa in the all too familiar phrases that were the conventions of the war — “REGRET TO INFORM YOU ADVICE HAS BEEN RECEIVED FROM ROYAL CANADIAN AIR FORCE CASUALTIES OFFICER OVERSEAS THAT YOUR SON....”. The next day, a Canadian National Telegraph and Cable Company messenger, rounded the corner of Portage Avenue and pedalled up Thompson Drive. Halfway up the block on the right side of the street, he dismounted from his bicycle, reached into his shoulder bag and pulled out an envelope addressed to Mrs. W. J. Bingham, 245 Thompson Drive, Winnipeg. He walked up to the neatly-kept, storey-and-a-half home set 40 feet back from the street, paused at the door, took a deep breath and knocked.

A studio portrait of handsome Flying Officer Clifford Mervyn Bingham. The Second World War was a happy time for studio photographers, as every serviceman or servicewoman had their formal photos taken in uniform to share with family and sweethearts. These also were shared with hometown newspapers in the event of newsworthy stories such as the award of pilot's wings, arriving safely overseas, or reports of being missing or killed in action. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

In addition to Cliff Bingham, another Canadian was killed with the crew of Whitley EL-L. Pilot Officer Archie Durnell was a Navigator who grew up in Windsor, Ontario. Photo: Canadian Virtual War Memorial

A few weeks after receiving the telegram, Olive would receive a formal Ministerial Letter, likely signed by Charles “Chubby” Power, the Minister of Defence for Air, informing her that her son was listed as missing in action. The process for determining that Clifford was lost followed a well established protocol. Six months would pass as the RCAF awaited word from the Red Cross or German authorities of the very remote possibility that Clifford was rescued and made a prisoner of war. Six months later, on January 24, 1944, with all hope abandoned, a second letter was sent to Olive stating now that he was “Missing and Presumed Dead”. Two weeks later, on February 7, a third letter was sent after a death certificate was issued. In June, Olive received the “King's Message” with his condolences and gratitude. Though this process was the correct way to confirm Clifford's loss, the receipt of each letter must have offered a moment of renewed hope, followed by yet more pain.

In addition to informing his parents through this series of letters that he was missing in action, presumed dead and then for official purposes declared dead, a clerk in the Casualty Office of the Royal Canadian Air Force would, following receipt of a copy of his official death certificate, include Clifford Bingham's name, rank and serial number in yet another lengthy list of airmen killed in action. Once this was done, the clerk would send this letter to one of three approved companies—Henry Birks and Sons of Montreal, jewellers and silversmiths; Lackie Manufacturing Company, a commemorative medal manufacturer or Roden Brothers, a silverware and tableware manufacturer; both of Toronto—there to be added to an ever-growing order for sterling silver Memorial Crosses.

The Memorial Cross, often known as the Silver Cross for Mothers, is probably the one award from the Second World War that every mother in Canada prayed she would not receive. On 1 December 1919, King George V, on the advice of his Cabinet under Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden, created the Memorial Cross as a memento of personal loss and sacrifice on the part of widows and mothers of Canadian sailors, soldiers, and airmen who had lost their lives for the country during the First World War. This included widows and mothers of those whose post-war death was related to their war service. It took the form of a small (32 mm) sterling silver Greek cross bearing the Royal Cypher of King George VI (for the Second World War), the St. Edward Crown suspended from a purple ribbon and worn around the neck. Engraved across the back of the horizontal axis of the cross are the rank, name and service number of the deceased service person.

On June 3, 1944 Olive Bingham's Memorial Cross was made available to the chaplain of No. 2 Training Command of the RCAF (based in Winnipeg) who made arrangements to present it to her. The cross was presented in a small leather, silk-lined case sometime and most certainly her tears flowed when she opened it for the first time and turned the bright silver cross over in her hands to reveal her beautiful boy's name. One cannot imagine the finality of it all. In time, the cross would become a means to remember her beloved Clifford and she would wear it on Remembrance Day and recall the beautiful life that was taken. I have come to understand that, though men like Clifford Mervyn Bingham paid with their lives in what we call the “supreme sacrifice”, it is their bereft mothers, their stoic fathers, their sweet sisters and their little brothers who are conscripted to shoulder that sacrifice until the end of their lives.

Lieutenant Colonel Jack Bingham would have to put this tragedy in some hidden place for the time being as he prepared his regiment in England for the battle to come. Because, at 53, he was considered too old to command the 1st Battalion in combat, he returned to Winnipeg in 1944 to command the 3rd Battalion, Royal Winnipeg Rifles which were in reserve. There's no doubt he had the loss of his son as motivation to push his men to train hard for the final victory. His burden would be lifted upon his death in Miami, Manitoba in March of 1953. Olive had two younger children to support on the home front and suffered Clifford's loss with dignity and sadness until her death at age 92 in 1986.

A photo of the Bingham family (L-R: Olive, Jack, Jean and Billy) as they greeted Jack on his return from England in 1944 to begin training the reserve 3rd Battalion of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles. They all look relieved and happy, but their smiles hide the damage done to them by Clifford's death. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

Cliff's younger sister Jean at age 18. She posed for the photo after turning 18 in 1942 and sent it to her father overseas as a Christmas gift. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

Young William Gordon “Billy” Bingham loved and admired his older brother and Cliff's death left him without his role model and hero. Later, Billy, inspired by his brother, became a bush pilot, flying up north and in British Columbia. He was a bush pilot on the west coast of Canada when he was killed in an airplane accident in October of 1979. He was returning to Squamish, British Columbia from Toba Inlet, north of Powell River in a Cessna 172 when heavy fog obscured Howe Inlet and the small airport they were to land at. Bingham circled overhead for half an hour hoping for a break in the fog, but ran out of fuel and crashed into Darrell Bay while trying to get the Cessna down. There were three aboard including Bingham and only one passenger survived, rescued by a pair of fishermen in a canoe who were out checking crab pots. For the second time in her life, Olive would have to face the loss of her son to an airplane crash.

Perhaps during his training and because his brother was his powerful inspiration, Olive's Memorial Cross ended up in Billy's possession long before his mother's death. Later, and before his death in the flying accident, Billy and his wife would divorce. The Memorial Cross became just one small unnoticed thing tossed into the bottom of his wife Margaret's jewellery box—a box she took with her in the separation. After Olive's death on 1986, the memory of Clifford Mervyn Bingham, cast in the form of a small silver cross, disappeared into the past, much the way relationships and love are left to fade away.

That left Clifford's beautiful sister Jean to hold strong to Clifford's memory. For a time she worked at CKRC, a Winnipeg radio station where she met and eventually married journalist George Brimmell in 1953. Their only child, Clifford Bingham Brimmell, named for her lost brother, was born in 1956. I first met Jean's son Cliff in 1986, the year his grandmother Olive died. Like his namesake, Cliff was handsome, easy going, kind hearted, a talented writer and a good friend. Many years ago, Cliff had told me the story of his lost uncle and how his mother missed him so, all these years later. He told me about a program in Manitoba that named previously unnamed lakes and other major geographic features (bays and islands) after the province's more than 4,200 war dead.

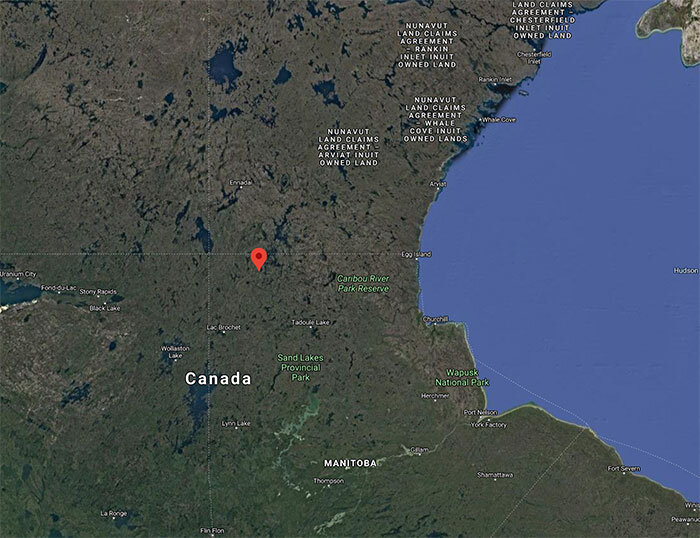

Bingham Lake lies at the very top of the province of Manitoba near the border with Nunavut Territory. Photo: Google Maps

Bingham Lake is so remote, that likely no one has yet put a canoe on its surface. Whitish areas show where the 3-kilometre long lake's surface has been disturbed by high wind gusts. Photo: Google Maps

A few months ago, I got an email from Cliff, who I hadn't heard from in a few months: “Hey if you've got time for breakfast or coffee sometime soon, I've got a great story for you!” So, we made arrangements to meet at 7 AM the following Wednesday at Eddie's Diner on Bank Street below my office. Cliff was waiting in a booth when I arrived. We were the only early birds. I ordered eggs and sausage and nodded sleepily when the server proffered coffee while Cliff pulled out a manila envelope and placed it on the table. He started into a story about how his son Jesse had received a friend request on Facebook asking if he was related to George Brimmell. To make a long story short, Cliff went into explaining that through Jesse, he had made contact with a woman named Heather Neill, a citizen of the small city of Vernon in the interior of British Columbia. Several years ago, Neill and her husband were filling up with gas at the Petro Canada station at the corner of 43rd Street and 25th Avenue in Vernon when they spotted a small wooden jewellery box lying at the back of the station, obviously discarded by a thief after taking all the valuables from it. Although it contained only a small number of small items, mostly broken (a couple of ladies' watches, a pin and other trinkets), the Neills contacted the local RCMP but were told the best way to get it back to the rightful owners was to try and track them down themselves

The Memorial Cross representing the terrible sacrifice made by Clifford Bingham and his mother was dumped on the ground behind this Petro Canada station in Vernon, British Columbia—a meaningless trinket to an unthinking thief. Luckily, it was found by someone who cared enough to find its rightful owner. Photo: Google Maps

They kept the box, but had no immediate luck finding the owner. A few years later, Heather was looking through the box again and this time she picked up one item that she had not really paid much attention to before—a small silver cross. This time, she turned it over and found something engraved on the horizontal axis—F.O. C.M. BINGHAM J22033. She would not yet know the heartbreaking story behind the cross, but she knew in her heart that it was important to someone. Through Veterans Affairs' Virtual War Memorial, she found the basics about Clifford—his age, date of his death and most importantly, the names of his parents. Armed with this information they contacted their local newspaper, the Vernon Morning Star and in mid-December of 2019, a story ran in the paper about their find and their desire to get the Memorial Cross back in the hands of Clifford Bingham's family.

Two of the items in the stolen jewellery box were Olive Bingham's Memorial Cross and a silver cloisonné British Empire Service League—Canadian Legion lapel pin that once belonged to Lieutenant Colonel Jack Bingham of St. James, Manitoba. Photo: Brendan Shykora, Vernon Morning Star

A friend did some research and was able to determine that the only living member of the family was Clifford's sister Jean, now Jean Brimmell. In January, Jean's grandson Jesse got the message on Facebook and within a matter of a few weeks, Cliff was sliding Olive's Memorial Cross out of the envelope onto the Arborite surface of a banquette table at Eddie's Diner in Ottawa.

The back of Mrs. Olive (Park) Bingham's Memorial Cross with the name of her first child engraved. I can imagine her thumb rubbing across this inscription while she struggled to bring up memories of her son with so much promise. Photo: Dave O'Malley

I had always wanted to write a story about Cliff's namesake and long-lost brother of his mother. I had known and respected the cheerful and intelligent Jean Brimmell for years now, and for much of that time I had wanted to research and write a story about Jean's brother but never got around to it. Now, I had a real story to tell of a Memorial Cross that made a long journey home.

However, a few weeks later, Cliff called me again. This time he had bad news. The evening before, he was sitting at a Tim Hortons restaurant chatting with some colleagues from the Ottawa Rowing Club where he is a coach. At one point he noticed a familiar local vagrant coming into the restaurant, a dishevelled and mentally ill man he had seen many times before walking and panhandling in the streets of his downtown Ottawa neighbourhood. But Cliff, being Cliff, went back to chatting with his friends and didn't think twice about his knapsack containing his laptop and the manila envelope which he had placed on a shelf behind him. When the chat was over and the coffees consumed, Cliff and his friends got up to leave and that's when he noticed that his knapsack and ball cap were gone. He guessed right away who had taken it and even one of his buddies confirmed he saw the man take it but had thought it belonged to the thief.

Staff at the Tim Hortons confirmed who stole the knapsack through security video and Cliff spent hours that night combing the local park and streets looking for the second thief—to no avail. When he called me the next morning he was feeling terrible about losing his Grandmother's Silver Cross after the incredible journey it took to find its way home, but he said he was getting in his car and was going to search for the man who had stolen the cherished family memento. I wished him luck, but I was sure the contents of the bag had been sold in a few hours to feed whatever habits the man had. It was, I thought, a sad way for the cross to be lost forever.

Three hours later, Cliff called me again with the good news I was not expecting to hear. After driving around downtown Ottawa for an hour or so, he spied the man walking along the street and wearing Cliff's hat. He pulled ahead of him by a block and dialled 911 as he watched him from a safe distance. While still explaining the situation to the police over the phone, a squad car rounded the corner and pulled up next to Cliff. Within a few minutes they had the man detained and convinced the thief to take them back to his flophouse, where they were able to retrieve the manila envelope containing the cross. So happy to get the Memorial Cross back, and Cliff being Cliff, he didn't ask the man about the laptop or knapsack and instead gave him $20.00. It tells you a lot about Clifford Bingham's nephew that he felt sorry for the clearly messed-up man who had stolen the knapsack. He may be one of the most forgetful friends I have, but he is one of my best.

There is a long thread to this story that started at St. Eval on that fateful morning and followed a search pattern over the Bay of Biscay; that dove with the Whitley into the cold Biscay water and emerged in the typewriter ribbon of an RCAF clerk in 1944; that reappeared in the hammer strokes of an engraver at a silversmith and then year after year wrapped like a purple ribbon around Olive's neck on Remembrance Day; that lay unseen at the bottom of a red flocked jewellery box for years more before being dumped by a thief under the mercury vapour light of a gas station a thousand miles from Winnipeg; that was found by a curious and compassionate couple and written in the lines of a local newspaper; that found its way home only to be lost again; that would not die and compelled Clifford Bingham Brimmell to drive his own search pattern in the streets of Ottawa until it was found again.

Now that's a story worth waiting to tell.

By Dave O'Malley,

for Jean Audrey (Bingham) Brimmell

Flying Officer Clifford Mervyn Bingham

Clifford Bingham was born on November 23, 1920 near the tiny farming village of Miami about 100 kilometres southwest of Winnipeg, Manitoba. He was the first child of Lieutenant Colonel William John “Jack” Bingham, MC and Bar, VD, and his wife, the former Olive Josephine Park. His father's First World War attestation papers indicate he was a farmer, but he was also a highly decorated and promoted veteran of the war. As a Captain and then acting Major in the 10th, 32nd, 222nd Battalions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (Royal Winnipeg Rifles), Bingham was mentioned in despatches and awarded the Military Cross twice for gallant and distinguished service in action. He was severely wounded by a gunshot or shrapnel to the head in October, 1915. After surgery, he was listed for a long time as dangerously ill and took two months to recover and then was sent back to active service. In 1918, he was hospitalized in England with something called Jacksonian Epilepsy — seizures caused by the damage to his brain. Once demobilized, Jack returned to Manitoba, settling near Miami and farmed until 1928, when, because of his war injuries he stopped farming and went to work for the Manitoba Hydro Commission, moving the family to a suburb of Winnipeg known as St. James.

Young Cliff would eventually get a pair of siblings—a sister named Jean Audrey, born two years later and a little brother named William Gordon, born four year after Jean. Despite the tough years of the depression, Cliff grew up happy and relatively healthy. In 1929, he was hospitalized with scarlet fever and had his appendix out in 1936. He would later state on his attestation papers that he played all sports, but was not exceptional at any.

A photo of a young Cliff Bingham and his little sister Jean on the steps of their home. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

In the late 1920s, Cliff and his sister Jean sit atop the family car as their mother looks on smiling. One looks at this photo and sees the bright promise that was the life of young Clifford Mervyn Bingham and feels the loss deeply. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

Cliff Bingham shows his sister and brother and family German Shepherd a bird he has just killed with his rifle on the banks of the Assiniboine River near their family home on Thompson Drive in the community of St. James, Manitoba. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

Cliff's little sister Jean flies her own airplane on the sidewalk of the family home in St. James. A quick search of “Airplane model EF-499” on the internet revealed other photos of this very same photo prop. Back in the late 1920s and early 1930s, a photographer went door to door in St. James, Manitoba dragging this wonderful model aircraft and taking pictures of kids. I wish they still did these sorts of things. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

A formal photo of the Bingham family in the mid-1930s. Olive and Lt. Col. Jack Bingham stand on either side of a teenaged Clifford while in front are his two siblings—sister Jean and younger brother Billy. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

Cliff completed Grade 11 (Junior Matriculation) at St. James Collegiate, after which he enrolled in an automotive technology course in college. While still in school, he joined the Fort Garry Horse, a non-active militia unit based in Winnipeg. When war was declared by Canada in September 9, 1939, Cliff, likely inspired by his father's military career and his passion for flight (as a teenager, Cliff loved to build aircraft models), was quick to enlist in the Royal Canadian Air Force. He was just 18 years old.

Upon acceptance in the RCAF, Cliff, suitcase in hand, said goodbye to his parents and siblings at Winnipeg's Union Station on Main Street and boarded a train for Toronto. Here, he reported to the RCAF's Toronto Manning Pool where he spent a month before moving on to RCAF Station Trenton. He was at Trenton (possibly doing guard duty) until the beginning of May 1940 when he was finally sent to No.1 Manning Depot in Toronto and his RCAF career began. Having had experience with auto mechanics, Cliff was selected to attend to No.1 Technical Training School (TTS) in St. Thomas, Ontario, there to train as an Aero Engine Mechanic. No.1 TTS was housed on the grounds of the old Ontario Psychiatric Complex and housed up to 2,000 student technicians at a time.

The cover of The Aircraftman, a monthly publication produced at No.1 TTS, St. Thomas, Ontario, depicting the importance of the technical skills of mechanics, fitters and other ground crew in keeping RCAF aircraft in the skies. Note that Newfoundland and Labrador are not included in the red of Canada. They would join Confederation in 1949. Photo: ElginCounty.ca

Cliff Bingham's parents— Lieutenant Colonel Jack Bingham and his wife Olive (née Park) are photographed at Camp Debert, Nova Scotia. Camp Debert was a staging and training area for units deploying overseas. It was here that Bingham's Royal Winnipeg Rifles trained and prepared for duty overseas early in the war. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

Leading Aircraftman (LAC) Clifford Bingham poses proudly with his father (right) Lieutenant Colonel Jack Bingham, MC, VD, Commanding Officer of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles. Known as the “Little Black Devils”, this regiment would earn hard fought battle honours during the Northwest Rebellion, the Boer War, the First World War (including Vimy), the Second World War and the War in Afghanistan. This photo was likely taken after he had completed initial aircrew selection training No 1 TTS as he is wearing LAC propeller badges on his sleeves. Since his father and another Army officer are present, it possible that this was when he was at No. 8 SFTS and was visiting his father who was training with his Royal Winnipeg Rifles in Camp Debert, Nova Scotia. The other officer was apparently the regimental chaplain. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

Though Cliff was studying aircraft mechanics, it was evident from his actions there that he longed to be a pilot. While at St. Thomas, Cliff signed up for private flying lessons at the nearby London Flying Club which operated from an airfield at Lambeth, Ontario. There he paid for 8 hours of dual instruction followed by another five hours of solo flight. Cliff graduated as an Aero Engine Mechanic (AEM Class B) at the end of January of 1941 and then took a train to No. 8 Service Flying Training School (SFTS) in Moncton, New Brunswick, there to work on the school's many Harvard and Anson aircraft. He arrived at the end of January, 1941, and worked maintaining aircraft engines for the next 15 months. While at Moncton, he played on the inter-squadron volleyball team and took a course to improve his mathematics skills, hoping to be selected for aircrew training. For a young man like Clifford Bingham who had joined specifically to be a pilot, who had already begun private flight training and who stated that his one hobby was model aircraft building, fixing airplanes in a hangar while young men just like him took those airplanes aloft, was likely extremely frustrating. Despite having trained him as a mechanic, the RCAF finally relented in April of 1942 and sent him orders to report to No. 3 Initial Training School (ITS) in Victoriaville, Québec.

Before Cliff Bingham did his Elementary Flying Training on Fleet Finches at No. 17 EFTS in Stanley, Nova Scotia, he spent a few months at No. 3 Initial Training School at Victoriaville in Quebec's Eastern Townships. Here Bingham (right) and some friends snack on something (possibly patates frites?) they have just bought at Lou's Restaurant in the small town of Richmond, Québec, about 50 kilometres from Victoriaville. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

There were seven Initial Training Schools across the country where young men who had been selected for aircrew training were taught, tested and sorted according to abilities and pressing demands. Here they studied theoretical subjects and were subjected to a variety of tests. Theoretical studies included navigation, theory of flight, meteorology, duties of an officer, air force administration, algebra, and trigonometry. Tests included an interview with a psychiatrist, the 4-hour long M2 physical examination, a session in a decompression chamber, and a "test flight" in a Link Trainer as well as academics. Those deemed good material for flying training would then be assigned to an Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS). During his time at ITS, Cliff was judged to be “Neat, Retiring, Dependable, Ambitious and Keen". After three months, and a promotion to Corporal, Clifford received the good news he was hoping for. He was posted to No. 17 EFTS at Stanley, Nova Scotia, there to begin his flight training on Fleet Finches. He arrived there on July 4, 1942 and completed the syllabus by August 29, when he was struck off strength and ordered to No. 2 SFTS at Uplands in Ottawa. Cliff impressed his instructors at Stanley, who summed him up with high praise: “Excellent material. Far above average. Very capable, quiet, keen and reliable. Exceptional flying ability in all phases.” He flew a total of 85 hours — both dual and solo and graduated second in his class. There is no doubt that Cliff had a bright future ahead of him in the wartime Royal Canadian Air Force.

Corporal Cliff Bingham (left) and a pal say goodbye to friends from the passenger door of a rail car. Taken in August of 1942, it was likely taken at the train station at Stanley, Nova Scotia en route to No. 2 SFTS at Uplands there to begin flying Harvard trainers. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

Cliff Bingham joined Course No. 63 at No. 2 SFTS Uplands in Ottawa, one of the larger of the advanced flying schools in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. It's not known how many of these 29 graduated, but Cliff (third from left in the front row) was second in his class overall. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

A great shot of Cliff Bingham flying a Harvard trainer over the snow-covered Ottawa Valley near No. 2 SFTS Uplands in late November or early December of 1942. In order to see his face better for the shot, Cliff has slid back the canopy which no doubt let in a thundering stream of freezing air. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

Cliff Bingham arrived in Ottawa for his service flying training on the last day of August, 1942 and there he completed 225 hours of dual and solo flying on the Harvard advanced trainer. His wings parade was on December 18 and he was promoted to Sergeant, pending a recommendation for a commission. Once again he graduated second in his class of 29 student pilots and left with another glowing assessment: “High average student. Progressed quickly. No serious faults. Appearance, bearing and general deportment very good. Respectful, cooperative type. Shows plenty of determination and initiative. Recommended for a commission.” Upon graduation, all students were allowed to state their preference for further training — on fighters, bombers etc. Cliff's preference was to become a reconnaissance pilot and his strong showing during training and his rank in the results, helped him get his wish. He received orders and a travel voucher for a train trip to Summerside, Prince Edward Island, where he was posted to No. 1 General Reconnaissance School, arriving there on January 4, 1943.

While at No 1 General Reconnaissance School at Summerside, Cliff Bingham's commission came through, earning him a new officer's service number and requiring a new photo for his identification card. Photo: From Cliff Bingham's service file, Library and Archives Canada.

In a letter to his father from RCAF Station Summerside, Cliff's pride and excitement at being just made an officer in the RCAF was clearly evident. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

Cliff Bingham photographed in the winter of 1942-43 at Summerside P.E.I. with his new Pilot Officer stripes on the epaulettes of his great coat. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

A wonderful image of Clifford Bingham at the reigns of a one-horse cutter in Summerside P.E.I.. The caption in the back written in Clifford's hand is the inscription: “Acme Taxi Co. “Drive Ur Self” Anywhere in Town for 25 cents.” Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

Certainly, Cliff's dream would have been to become a Spitfire or Mosquito Photo Reconnaissance pilot. At No. 1 GRS, he flew twin-engine Avro Ansons on long distance anti-submarine and training patrols and participated in the Battle of the St. Lawrence, the two and a half year-long anti-submarine operation in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, upper St. Lawrence River, Strait of Belle Isle and Cabot Strait. Cliff would not do so well at Summerside as he had done during flight training. He graduated 15th out of a class of 19. His instructors commented that he was a “Hard-working pupil who tends to panic in the exam room. Could have done better than his marks show... but with more experience he should make a reliable G.R. pilot.” He was recommended for torpedo bombers first and then land-based reconnaissance.

He finished at Summerside on March 6, 1943 and with a requirement for Coastal command crews to fight the U-boat menace which was just then at its peak, he was posted to a Bomber Command Operational Training Unit at RAF Abingdon in Great Britain, travelling there aboard a troopship. That OTU operated a small detachment of anti-submarine Whitleys at RAF St. Eval. On June 20, 1943, Clifford Bingham flew from St. Eval on his fifth and last operational training flight. And that's where the story began.

Pilot Officer Cliff Bingham sheltering from the wind and rain aboard a troopship on its way to Great Britain. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

Another dramatic photo of Cliff Bingham aboard a troopship heading across the Atlantic at the height of the U-boat wars. Photo: Jean (Bingham) Brimmell Collection

I would like to thank Cliff Bingham Brimmell for his cheerful assistance in providing images and family background for this story. His uncle and namesake would be very proud of him. As well, I thank my friend Tim Dubé for helping me interpret Clifford Bingham's service file cards outlining the sequence of official letters and awards and for his constant and encouraging help over the years. With the help of his critical eye, I have managed to avoid many mistakes and omissions.

Dave O'Malley