THE LAST FLIGHT OF BUFFALO 33

It was all over in a matter of seconds. Too few seconds for the two men inside to ever understand what was happening. A loud cracking report on the left, another on the right, a flash of orange light. The Mosquito’s nose dropping like an anvil, sagging, engines screaming, maps and grit rising in the cockpit. The leafless forest below rising like death, the discs of the propellers scything, a flash of white birch. And then oblivion.

November 30, 1944 was a low, grey morning in Cumberland County, Nova Scotia. But then, it was almost always that way in November, squeezed as it was between the soon to be ice-choked waters of Northumberland Strait and the tidal surges up the Minas Basin to Cobequid Bay at the head of Fundy. November was sleet and snow and rain and lowering clouds. The weather would take your life if you weren’t careful. But weather had nothing to do with the crash of Mosquito KB278.

Cumberland and Colchester counties form the Isthmus of Chignecto, the arm of land from which the rest of Nova Scotia clings to Canada. Low and marshy over much of its surface it rises steadily as it reaches south. At the point where Cumberland and Colchester meet, it’s high and rugged and even today is mostly bush and rock. Lumbered out long ago, not much happens here today except quarrying, downhill skiing and in the future, wind farming.

At 9 a.m. that day at RCAF Station Debert, Nova Scotia, the weather was not pleasant, but neither was it bad enough to cancel flying. When Pilot Officers Don Breadner and Brian Bennett came out of the briefing by Chief Gunnery Officer Flight Lieutenant Denis Northcott, they signed the log and opened the door of the operations room onto the apron outside the hangar at No. 7 Operational Training Unit. The wind was gusting between 10 and 20 knots, sweeping drizzle across the wet concrete. The sky was leaden and wintry, the temperature just a few degrees above freezing. Intermittent rain was called for over the next few hours, even the odd snow squall. The two men hunched their shoulders and quickly crossed the distance to the flight line to where de Havilland Canada Mosquito KB278 waited, glistening wet. Two equally miserable-looking aircraftmen stood, backs to the wind, waiting with a hand drawn accumulator trolley ready to start the two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines of the Mosquito. Next to the battery cart on the port side was a large red chemical fire extinguisher on a dolly. A rubber cable snaked from the trolley up to a port on the side of the aircraft.

Before climbing in through the crew door on the starboard nose, both men glanced back at the pitot tube on the vertical stabilizer to make sure its cover had been removed. Breadner, the pilot, climbed the crew ladder up through the narrow hatch first, followed by Bennett his navigator. Both men squirmed and shifted into their seats — Breadner to the left and slightly ahead of Bennett.

They settled into their pre-flight checks and engine start routines, happy to be out of the wind and freezing drizzle. Nearby on the ramp, a twin-engine Fairchild (Bristol) Bolingbroke aircraft (RCAF Serial 9171) was trying to start a balky engine. It was painted in a thin coat of yellow paint stained with oil and dirt. At the controls of the Bolingbroke was Flight Sergeant Tom Jasieniuk from tiny Krydor, Saskatchewan, a staff pilot with the school gunnery flight. He was still trying to get his last engine started when Breadner and Bennett got clearance to taxi Mosquito KB278, callsign Buffalo 33, to the active runway. The Bolingbroke, call sign Yarrow, was critical to the day’s training exercise for it would be acting as a target aircraft upon which Buffalo 33 would make cine-gun attacks. Jasieniuk would fly back and forth along Tow Line One — a pre-determined east west track established over Cobequid Bay from just south of Debert, west to Economy Point. On that day, he would fly solo and would not be towing a drogue while he flew the line.

An RCAF Mosquito at No. 7 OTU, Debert, Nova Scotia in 1944.

The Fairchild-built Bristol Bolingbroke was a variant of the British-designed Bristol Blenheim light bomber/reconnaissance aircraft and was built in Montreal. Outdated and outclassed for combat operations, they were relegated to coastal patrol, liaison and target-towing duties across Canada. Bolingbroke 9171, which Jasieniuk was flying that day, was a dedicated target tug and as such was likely painted overall in yellow paint (as above) to make it more visible to aircraft targeting it. Some also carried the “Oxydol” paint scheme of broad diagonal black and yellow stripes.

By the time Breadner was ready for take-off, Jasieniuk had the balky Bristol Mercury engine running smoothly and he moved off the flight line. Jasienuik’s “Boli” was not equipped with a radio, so Buffalo 33 and the Debert tower (Callsign Dewitt) could only wait until they saw the Bolingbroke taxi to the active runway. As Jasienuik began his take off roll, the tower radioed permission to Buffalo 33 to “scramble”. Farther down the flight line another Mosquito/Bolingbroke pairing was also warming up for Tow Line Two. To the north and west of the airfield the cloud was now pressing down on the hill tops. The time was 0920 hrs.

No. 7 Operational Training Unit

There were basically five stages of training in the making of an operational pilot of the Royal Canadian Air Force in the Second World War. It was the same whether you flew advanced fighter aircraft, bombers or transports. After enlistment, you were given the lowest rank in the air force—Aircraftman Second Class (AC2) and were posted to one of ten Manning Depots across the country, usually to the one closest to where you enlisted. Here you would spend four to five weeks learning to be an airman — spit, polish, marching, saluting — the routine stuff common to every airman. Here you were tested to determine whether you were possible air crew or ground crew material. Often, if there was a training bottleneck after Manning Depot, you were assigned “tarmac duty” somewhere, often guarding something in no need of guarding. If you were selected for air crew training (pilot, navigator, flight engineer, bomb aimer, air gunner or wireless operator), you were sent for another month to one of seven Initial Training Schools (ITS) across Canada, again usually close to the Manning Depot you went through. Here you would be taught the basic theories of navigation, aerodynamics, meteorology, duties of an officer, air force administration, algebra, and trigonometry. Here you also underwent an interview with a psychiatrist, a four-hour long physical examination, a session in a decompression chamber, and a "test flight" in a Link Trainer.

If, at the end of ITS, you were lucky to be selected for pilot training, you were promoted to Leading Aircraftman (LAC) and were posted to one of 36 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) airfields recently constructed across Canada. You wore a propeller badge on your sleeve and a white aircrew training flash in your cap. You were moving up. Here you would take instruction on a simple and forgiving training biplane aircraft like the de Havilland Tiger Moth or the Fleet Finch. Later in the war, monoplane Fairchild Cornell training aircraft would replace the others. Your time at EFTS would last about eight weeks after which you would have put around 50 hours into your log book — both dual and solo.

At the successful completion of EFTS, student pilots were assessed and channeled into two streams — single-engine and multi-engine. Single meant fighters, multi-engine meant bombers, transport and coastal patrol. Depending on your stream, you went to one of 29 Service Flying Training School (SFTS) airfields across Canada for 16 weeks of advanced flying training. Four of these airfields were dedicated to single-engine training, 12 to multi-engine and the other 13 to a combination of both. In the latter 13 schools, pilots took instruction on single- or multi-engine aircraft, but not both. For single-engine training there was only the North American Harvard/Yale training aircraft—perhaps the most ubiquitous trainer in the Allied air forces for the next 15 years. For multi-engine training there were three platforms for instruction — the British-designed Avro Anson and Airspeed Oxford or the American Cessna Crane. When you successfully graduated from SFTS after an additional 100 hours of flying time (dual and solo), you were finally awarded your pilots wings and a promotion to Sergeant or Pilot Officer. It was the greatest day of any pilot’s career.

An aerial view of RCAF Station Debert in the Second World War, looking north over the rugged hills of Colchester County . Photo: RCAF

The last stage of training for new pilots before being posted to an operational squadron overseas or with those of the Home War Establishment (HWE), was learning to fly the type of aircraft and the type of missions required at their final operational posting. There were two routes through operational training — shipping overseas and training there with an Operational Training Unit. Spitfire OTUs were all overseas as there were no operational Spitfires on Canadian soil. As well, bomber OTUs were largely overseas, especially Heavy Conversion Units where pilots transitioned to four-engine types like the Lancaster and Halifax.

In Canada, there were seven OTUs. Pilots selected for one of the Hurricane fighter squadrons of the Home War Establishment went to No 1 OTU in Bagotville, Quebec, while those destined for coastal and anti-submarine patrol with the HWE, or Liberators went to other OTUs on either coast.

No. 31 OTU at Debert was the first OTU to be built and was originally created by the Royal Air Force to train pilots for long-distance over-water patrolling, anti-submarine work and for selected pilots and crews to ferry American and Canadian-built aircraft across to Europe in the early stages of the war. No. 31, was handed over to the RCAF in 1944 and re-designated No. 7 OTU. From that point, the unit trained intruder crews on the Canadian-built de Havilland Mosquito. At the time that Breadner and Bennett were posted there, the school’s commander was none other than Wing Commander Robert “Moose” Fumerton, DFC and Bar, AFC of Fort-Coulonge, Quebec, who was a Battle of Britain and Battle of Malta fighter pilot with 14 victories to his credit.

One of the most beautiful aircraft designed in the Second World War, the de Havilland Mosquito was made mostly of wood and plywood as a way to get around shortages of vital aircraft aluminum.

Related Stories

From the Glebe

Click on image

For young men who had once hoped to fly single-engine fighters, but were then channeled through a multi-engine SFTS course, finding out that they were posted to a Mosquito OTU was the best news they could hope for — just as good a going to a Spitfire course. The de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito was a British twin-engined, shoulder-winged, multirole combat aircraft, introduced during the Second World War. Its fuselage, wings and empennage were constructed largely of wood earning it the nickname "Wooden Wonder”. The wing spars of the Mosquito, the primary structural components, were of a very complex design made entirely of wood constructed with new glue-lamination technology. Wikipedia offers up this description of this wing spar design:

The all-wood wing spars comprised a single structural unit throughout the wingspan, with no central longitudinal joint. Instead, the spars ran from wingtip to wingtip. There was a single continuous main spar and another continuous rear spar. Because of the combination of dihedral with the forward sweep of the trailing edges of the wings, this rear spar was one of the most complex units to laminate and to finish machining after the bonding and curing. It had to produce the correct 3D tilt in each of two planes. Also, it was designed and made to taper from the wing roots towards the wingtips. Both principal spars were of ply box construction, using in general 0.25-in plywood webs with laminated spruce flanges, plus a number of additional reinforcements and special details.

Breadner and Bennett

The two young men who waited patiently in the cockpit of de Havilland Mosquito KB278 at the threshold of the runway for Jasieniuk to get his second engine running came from two very different backgrounds. War had a way of making all things equal and the two men who never would have met in a peaceful world found themselves shoulder to shoulder in a claustrophobic cockpit under glowering skies. Breadner and Bennett were physically very similar. They were both 5’-8” tall and of slight builds. Bennett was a mere 137 lb. with a chest size of just 31.5 inches while the stockier Breadner weighed 148 lb. with a chest size of 36.5 inches. They were fit, compact and not too tall—perfect for the tight confines of the Mosquito fighter bomber. They had worked very hard to get to this point in their training. Two weeks from now, they would finish and, after nearly two years of training, be ready to join a Mosquito combat squadron overseas. Their confidence had grown steadily with each step, and finally, they were developing a deep sense of comfort with the operation of one of the most sophisticated aircraft of the day.

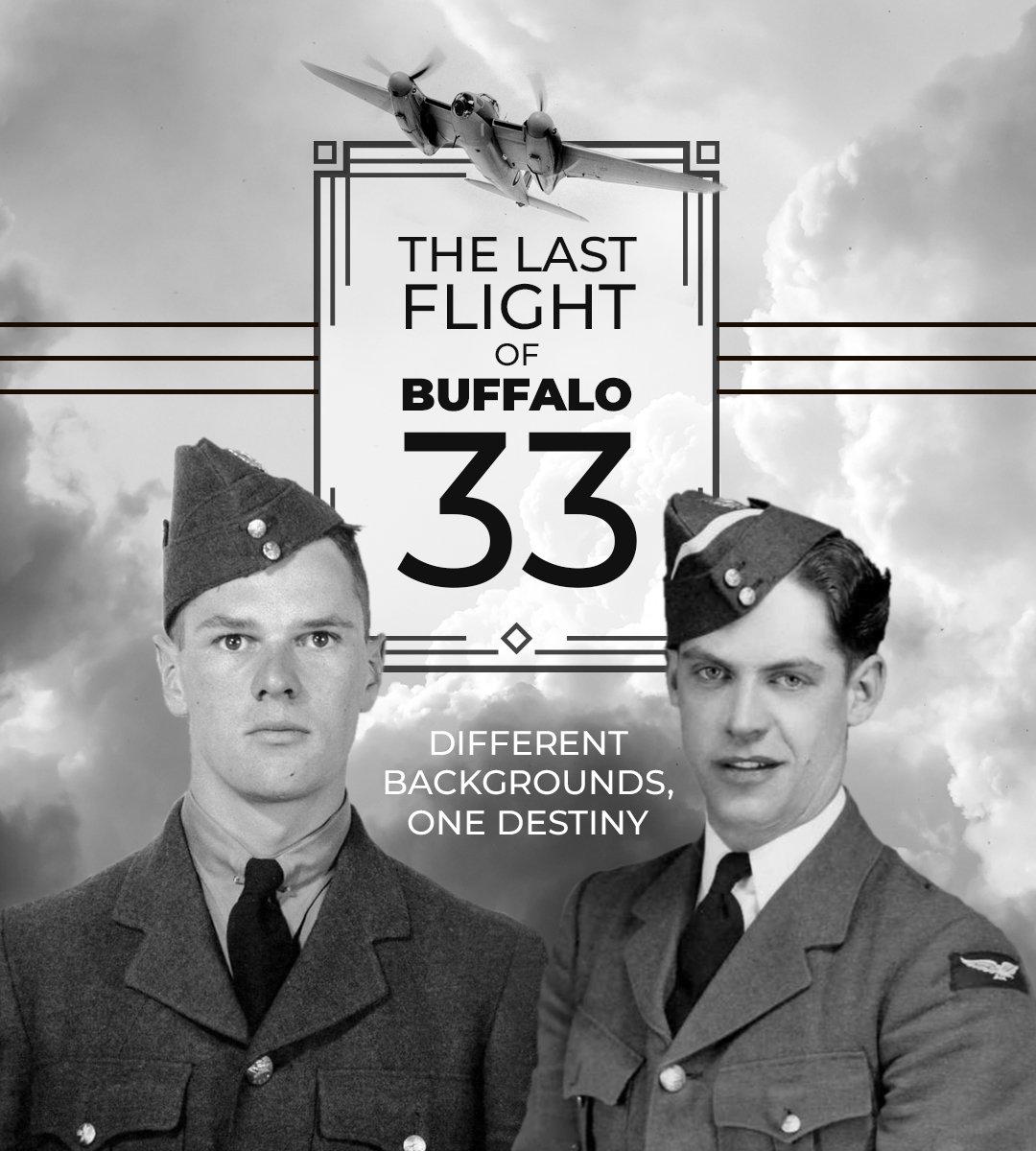

Pilot Officer Donald Lloyd Breadner, left, was the 20-year old son of Air Marshal Lloyd Breadner, Chief of the RCAF overseas. Growing up, he had met many important and sophisticated people, attended many political and military events and had even lived abroad with his family in Great Britain. Pilot Officer Kenneth Brian Bennett, 22-years old, grew up in a small farming community in Southern Alberta, worked on his father’s farm and had not seen much of the world when he enlisted in December that same year.

Don Breadner had just turned 18 when he enlisted straight out Glebe Collegiate Institute in Ottawa’s Glebe neighbourhood in 1942. Though he attended Glebe Collegiate, he lived outside the Glebe in a leafy downtown neighbourhood now known as the Golden Triangle. The house at 54 Cartier Street was a short four-minute walk from the “Temporary Buildings” complex at Cartier Square, massive rambling wooden structures, which housed the wartime offices of Canada’s armed forces including the headquarters of the Royal Canadian Air Force. The location of the house was clearly chosen by Breadner’s father who, at the time, was none other than Air Marshal Lloyd Samuel Breadner, Chief of the Air Staff of the RCAF. By November of 1944, Air Marshal Breadner was Air Officer-in-Chief, RCAF Overseas, in charge of all operational flying outside Canada’s borders. Lloyd had left his wife, three grown daughters and one son to take command of the RCAF in London, England.

Lloyd Breadner was one of the most important figures in the Royal Canadian Air Force prior to and throughout the Second World War. He came from a small milling and farming community west of Ottawa called Carleton Place where his father was a jeweller and silversmith. This tiny rural village was known in local Ottawa newspapers as “The Nursery of the Air Force” because a number of its young men learned to fly as civilians at the Wright school of flying in Augusta, Georgia and Dayton, Ohio before going overseas in the First World War. Several of these Carleton Placers became multiple aces including Breadner and Roy Brown, the man who was involved in the shooting down of the “Red Baron”, Manfred von Richthofen. Brown was in the process of attacking von Richthofen in his red Fokker Tri-plane, when the German uber-ace was shot down by Australian ground fire. Tiny rural Carleton Place was home to several aces of the First World War—Breadner (10 victories), Roy Brown (11). Stearne Edwards (17), Murray Galbraith (6), Ken Conn (20), Harry Edwards (21).

UPPER LEFT Air Marshal Lloyd Samuel Breadner, by Yousuf Karsh (1942). UPPER RIGHT Lloyd Breadner (left) was one of Canada’s early aviators, learning to fly at the Wright School in Dayton, Ohio before joining the British Royal Naval Air Service in December of 1915. Here we see him in a Wright Flyer getting preflight instruction from Jack Simpson of Guelph, Ontario. Simpson, an officer in the Royal Flying Corps, would be killed in France on Dominion (Canada) Day the next year. LOWER LEFT: Lloyd Breadner was a fighter pilot with the Royal Naval Air Service during the First World War. He is seen here in Sopwith Pup His Majesty’s Aeroplane (HMA) “HAPPY” of No. 3 Naval Squadron at Marieux, France in April of 1917 when he held the rank of Flight Commander. LOWER RIGHT: Lloyd Breadner was from the same small rural town as Captain Roy Brown (Pictured), famed for his dogfight with Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron.

After learning to fly in America, Lloyd Breadner joined the Royal Naval Air Service. In 1917, he was posted to 3(N) Squadron which was attached to the Royal Flying Corps. In April of 1917, Flying a Sopwith Pup he had nicknamed “HAPPY”, Breadner scored his fourth of 10 victories by shooting down a Gotha GIV heavy bomber of the Imperial German Air Service — the first Gotha bomber shot down by a British fighter over the Western Front. It was one of three enemy aircraft he shot down in April. He was awarded a Distinguished Service Order for:

… “conspicuous gallantry and skill in leading his patrol against hostile formations. He has himself brought down three hostile machines and forced several others to land. On the 6th April, 1917, he drove down a hostile machine which was wrecked while attempting to land in a ploughed field. On the morning of the 11th April, 1917, he destroyed a hostile machine which fell in flames, brought down another in a spinning nose dive with one wing folded up, and forced a third to land.”

Lloyd Breadner’s Sopwith Pup mount in the First World War is a favourite of builders — whether a full-size flying replica or a scale model. Photos: Left: Ron Eisele, Right: Ivan Ivan Bouinatchov of Aeroscale

Air Marshal Lloyd Breadner (Fifth from left) was used to power as demonstrated by this photo of Allied military leaders who accompanied Roosevelt, Churchill and King to the Quebec Conference at the Chateau Frontenac. Left to right: Lord Louis Mountbatten, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound, General Sir Alan Brooke, Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal, Breadner, Field Marshal Sir John Dill, Lieutenant General Sir Hastings Ismay, Admiral Ernest J. King, General Henry “Hap” Arnold, Admiral W D Leahy, Canadian Lieutenant General Kenneth Stuart, Canadian Vice Admiral Percy W. Nelles and General George C. Marshal.

Even Donald Breadner’s mother Elva was a leader in the RCAF world in the Second World War — as a long-time President of the RCAF Officer’s Wives Association. Photo: Yousuf Karsh

Breadner remained in the Royal Air Force after the First World War and was transferred to the Royal Canadian Air Force upon its inception in 1924. In 1935, he moved his family to London where he attended the Imperial Defence College near Buckingham Palace. By the Second World War, Breadner had risen to the rank of Air Commodore, Chief of the Air Staff. In 1941 he was promoted to Air Marshal. As Chief of the Air Staff, he lobbied the Canadian government and the RAF to establish a series of Operational Training Units on Canadian soil. Previously, Canadians sailed for the United Kingdom to continue their flying training. Thanks to Breadner’s pressure, several OTUs were established in Eastern Canada (Debert and Greenwood in Nova Scotia and Pennfield Ridge in New Brunswick) where recently-winged RCAF and RAF pilots and navigators, streaming out of advanced training across Canada’s British Commonwealth Air Training Plan could immediately start on their operational training.

During his time as Chief of the Air Staff, Breadner moved his family to Cartier Street. By 1944, when his son was flying Harvard aircraft south of Ottawa at No. 2 Service Flying Training School, he was given one of the most important command positions in the Royal Canadian Air Force at the time — Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, RCAF Overseas.

Lloyd Breadner’s new command required him to leave Ottawa for London, England where he would command all Canadian air force personnel and assets in the European Theatre. He left his wife Evaline (“Elva”) who was then head of the Air Force Officer’s Wives Association, three daughters Doris (herself married to an RCAF officer and pilot, Squadron Leader J. T. Reed, DFC), Joan (also married to an air force officer — Flying Officer John Ferguson Magor, son of the wealthy industrialist and President of National Steel Car, builders of Lysander aircraft in Canada) and 15-year old Anne, as well as his only son Donald and flew to London to take command. His authority in London gave him administrative control over both operational and staff personnel of the RCAF and brought him in close contact with the military leaders of all Allied services. A Wikipedia page for this command states:

The Royal Canadian Air Force Overseas Headquarters, often abbreviated to RCAF Overseas, was responsible for Canadian airmen serving outside Canada during and just after World War II. The headquarters was established on 1 January 1940 and it was based in London. Its main functions were to conduct liaison with the British Air Ministry, to provide a central location for personnel records, and provide general administration. As the War progressed, the Overseas Headquarters gained increasing administrative authority over Canadian personnel but never gained any significant operational responsibility for RCAF units and formations which were integrated into the RAF's command structure. [RCAF squadrons in Fighter, Bomber, Coastal and Transport Commands of the RAF]

The commander’s son

When the Second World War began, Donald Breadner was starting the 11th grade at Glebe Collegiate Institute. He had grown up surrounded by the upper echelons of leadership in the Royal Canadian Air Force, in the Canadian military in general and the Allied command at large. The family home on Cartier Street hosted dinners with old friends like Roy Brown (who was at that time still credited with shooting down the Red Baron), Victoria Cross recipient and ace Billy Bishop, and zeppelin-killer Robert Leckie — all First World War aces who were now at the top of the RCAF leadership hierarchy. I can see Donald listening in reverent wonderment as the old warriors spoke of their war flying experiences at the dinner table and command stresses over brandy in the drawing room. Every morning, his father left the house, briefcase in hand, dressed in the blue of the RCAF and emblazoned with the rank insignia of an Air Marshal and the ribbons of gallantry and military accomplishment. They lived a short, two-block walk to the bustling RCAF, Canadian Army and Royal Canadian Navy headquarters and teenage Breadner must have watched in awe and pride as streams of high-ranking officers and simple enlisted men and women heading to or coming from Cartier Square snapped their best salutes as he passed. There was no doubt in anyone’s mind, least of all his, that young Breadner was going to join the Royal Canadian Air Force the moment he was finished high school.

While still at Glebe Collegiate, Donald skipped school and with a group of eager young pilot hopefuls, walked into a recruitment centre in Ottawa at the end of October, 1942 and joined his father’s air force. On the attestation forms filled out by every member of the Canadian armed forces there is a section entitled “27: Names of Persons who can give references as to character and ability” Here, your typical recruit might write down the names of his employer, doctor or pastor. Of the four names Breadner listed, three were of this kind (his doctor, principal and a teacher), but the fourth was truly an indication of his family’s position in the upper echelons of the air force — Samuel Laurence DeCarteret, Deputy Minister of Defence for Air. No doubt knowing full well whose son Breadner was, the recruitment officer was particularly effusive in his recommendation: “Excellent type of youth — athletic, alert and responsive. Exhibits a keen interest to qualify as a pilot — well motivated— aggressive and co-operative. Should do well in training — above average material.” That being said, it’s also likely Breadner was all of those things. When interviewed by The Ottawa Journal following his enlistment, Breadner stated that he had “one ambition, and that is to be a fighter pilot.” The boys were granted a leave of absence without pay so that they could return and complete their semesters at high school.

Left: “Son, I’m proud of you.”. Air Marshal Breadner poses for an Ottawa Citizen publicity photo with his teenage son following the boy’s enlistment in the air force he commands. The Ottawa Journal reported that Donald and 11 fellow high school students “banded together and played “hookey” from school to apply for enlistment as pilots in the RCAF”. At right: Breadner (far right) and old friend David Heakes (next to him and also the son of a high-ranking RCAF officer, Air Commodore Francis Vernon Heakes) try their best to impress the drill corporal at Manning Depot in Lachine, Quebec. They have clearly just arrived from “Civvie Street” and Breadner is sporting his Glebe Collegiate varsity sweater.

After completing his Initial Training at Toronto, he was posted to No. 10 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) at Pendleton, Ontario about 50 kilometres east of Ottawa where he learned the fundamentals of flying on the Tiger Moth. He graduated from N0. 10 EFTS exactly a year after his enlistment and was posted back to Ottawa’s No. 2 Service Flying Training School at Uplands on Harvard course No. 93. He was close to home and could visit his mother on weekends when he wasn’t flying. Most certainly, if his father had not been in London, he would have been there to pin his wings on him and his classmates at their wings parade in April of 1944 as he had done for other graduating classes.

Air Marshal Robert Leckie, CB, DSO, DSC, DFC, CD, was not only in charge of training in the RCAF, he was a colleague and close personal friend of the Breadner family. As Donald Breadner faltered in his training, he went to bat for him. Photo:

Upon earning his wings, he joined his father as a qualified pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force. Under his belt, he had just 262 hours of solo and dual time, most of it in daylight flying. All of it, however was on single-engine aircraft. He was in line for a Spitfire, Typhoon or Mustang seat and he couldn’t be prouder. However, instead of continuing on single-engine fighters as expected, he, along with a fellow Uplands graduate, was posted to 36 Operational Training School (Mosquito) at RCAF Station Greenwood in Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley. He was part of a training experiment to see if recently-winged, single-engine pilots could make the transition to operational multi-engine fighter-bombers. Though the Mosquito was not a single-engine fighter, it was likely that the posting was not a disappointment for Breadner in that the “Mossie” was one of the most advanced, exotic, beautiful and challenging machines in the RCAF.

Breadner was taken on strength at Greenwood on May 11, of 1944. He flew a few refresher and assessment hours on Harvards and then began immediately training on the Mosquito. For a man who only knew one throttle since training began, suddenly having a pair of them in his hands proved to be too much of a transition. It would be a fair challenge if he was just transitioning to a rather docile multi-engine aircraft like the Avro Anson or Airspeed Oxford, but the Mosquito was a very high powered, high-performing aircraft, one that would be more challenging even than a Spitfire.

The powerful Mossie proved to be too much of a step for a brand new single-engine pilot and both Breadner and his colleague struggled to master its complexities. After just a few weeks, their training was ceased and the Chief Flying Instructor (CFI) suggested they undergo a period of training on the Airspeed Oxford and then Bristol Bolingbroke, implying they should be trained at an advanced flying training school. Things did no go as planned.

I found a letter in Breadner’s service file written by Air Marshal Robert Leckie to Breadner’s father in Great Britain when he found out about Donald’s predicament. If anything, it speaks to the fact that Breadner and Leckie were close and that he had his son’s back.

Dear Lloyd

My attention has today been drawn by A.M.T. [Air Member for Training — at the time AVM Joseph Lionel Alphege Albert de Niverville] to the unsatisfactory situation concerning the training of your son, Donald. I have taken some considerable interest in your son’s progress so that, accordingly, I am sorry that the situation in which he finds himself was not brought to my attention earlier.

As you know, Donald graduated from no. 2 S.F.T.S., Uplands, as a single engine pilot and, as an experiment along with one other officer graduate, was sent to No. 36 O.T.U., (Mosquito) Greenwood, N.S. I believe it is the practice of both in the United Kingdom and in Canada now that no S.F.T.S. graduates are sent to Mosquito O.T.U.’s but that the supply to these schools is supplied by ex-instructors from S.F.T.S.s with considerable flying background. The reason for this is that it has been proven very difficult for S.F.T.S. graduates to qualify on Mosquitos with the limited flying experience that they have had.

Your son failed to qualify on Mosquitoes at Greenwood not because of any lack of ability on his part, but purely due to lack of experience and the Chief Instructor appended to his Suspension of Training Report the following remarks:

“F/O Breadner was given 4:50 hours dual, all of which was circuits and landings. It was not possible to give time to other exercises as it was only during the last hour that progress was made. This is directly attributable to his very limited flight experience all of which is on singles. He would need about 8-9 hours dual before being able to carry out all the pre-solo exercises on which single engined flying presents a major problem, and even then would not have sufficient margins for emergencies. Were he to receive this course, he would be at a great disadvantage in another 60 hours when confronted with the day and particularly night operational conditions in the U.K. He is recommended for 20 hours Oxford [twin-engine training aircraft] flying including 5 hours night flying and 30 hours Bolingbroke including 10 hours night and then return to this unit.”

By the time Leckie had been informed of the problem and written to Breadner, Donald and the other officer had long since been transferred to No. 5 SFTS in Brantford, Ontario for further training on the twin-engine Avro Anson (from June 15 to August 15). Leckie seemed quite ticked off that Breadner had been transferred by Wing Commander J. K. Young, the Director of Airmen Personnel Services [D.A.P.S.] to an Anson school, ignoring the recommendation of the CFI at Greenwood to train on Oxfords and Bolingbrokes which had higher performance envelopes. While it was right to cease their training until they could get some multi-engine experience, the posting to a Service Flying Training School was surely a humiliating setback in their careers. Here, they were posted to a class of Leading Aircraftmen fresh from flying Tiger Moths or Cornells. He noted in his letter that “Obviously the requirements of the Chief Instructor had not been met and, in the opinion of the Training Division, familiarization on Ansons is not satisfactory for conversion to Mosquitoes.” By this time, however, Breadner had already completed the Anson course at No 5 SFTS in Brantford, Ontario. In the end, Leckie recommended that Breadner and his colleague be posted to the Central Flying School at Trenton, Ontario where they could get instruction on the recommended aircraft types. As a result, Donald Breadner found himself at Trenton in mid-August. Two months later on October 5, he finally had the proper training he needed to proceed with Mosquito intruder training — an additional 188.55 hours of multi-engine training in Ansons, Cranes, Oxfords, Bolingbrokes and Hudsons — far in excess of the 35 total hours the CFI had recommended. Added together with his previous Mosquito time, he now had as much multi-engine time as single-engine experience. He boarded a train at Trenton that same day and was back in Nova Scotia by the 6th. He joined Mosquito OTU Course No. 12 at No. 7 OTU, Debert Nova Scotia which started three days later.

Looking at all this high-level effort to get Breadner and his colleague trained up for a successful completion of the challenging Mosquito course, one can’t help but wonder if the same courtesies would have been afforded a pilot from a more ordinary background. In any event, Breadner was back flying Mosquitos and on November 30th, was paired up with a navigator by the name of Pilot Officer Kenneth Brian Bennett who went by the name of Brian. Bennett’s background could not have been more different than Breadner’s. Whereas Breadner had been brought up in the air force community, travelled widely and knew personally many of Canada’s military and political leaders and national heroes, Bennett grew up on a farm in Southern Alberta and never left it. The war would change that.

The farmer’s son

Brian Bennett came from a very large, hard-working Mormon family living and farming northeast of Raymond, Alberta. His parents were American-born, with Mormon values of abstention and hard work. He had eight sisters, all but one older than him, seven of whom were married and four brothers, one younger than him. Despite the fact that there was a 22-year difference between the youngest and oldest and that some of his sisters were living far from home, the Bennetts appeared to be a close, fun-loving family. The men stayed close to home before the war, helping out their father David Alma Bennett (who went by the name “Allie”) and mother Elna (Nel) on the family cattle and wheat farm. Judging by family photographs, which show well-dressed and well-groomed siblings, a well-kept farmhouse and new automobiles, the family farm was a prosperous one. With the war came pressures on the family farm as both Brian and his older brother Whit answered the call and enlisted— Whit in the army and Brian in the RCAF.

Brian Bennett, 18-years old, poses with the family’s brand new 1940 DeSoto sedan. Photo: Bennett Family Collection, Ancestry.com

Brian Bennett must have been a fun guy to be around based on these two photos. He was a terrific dancer and all the girls wanted a chance to dance with him. At right he poses with three of his eight sisters including the oldest Norma (41 years, at Back on right), the youngest Eloise (21 years, Bottom) and Maude (called Mollie by family, at left) on his leave in late August of 1944 after he was awarded his navigator brevet. Photos: Bennett Family Collection, Ancestry.com

Bennett enlisted on December 4, 1942 at the RCAF Recruitment Centre in Calgary, Alberta. His attestation papers reveal a healthy, hard-working farm boy who had little time for hobbies or interest in sports. Though he was a Mormon [who eschew alcohol, tobacco, coffee and tea]', he admitted to smoking 6-8 cigarettes a day during his pre-enlistment medical exam. In section 26 of his Attestation Papers where he is asked what air force duties he is enlisting for, he crossed out Observer, Air Gunner, and Wireless Operator, and selected only Pilot. In the end he would be trained in most of the things he did not want — Navigation, Wireless Operations and Aerial Gunnery.

Following his enlistment, he was posted to No.3 Manning Depot in Edmonton, Alberta. Already he was father away from home than he had ever been. Following two months at Manning Depot, he was sent to Regina, Saskatchewan for Initial Training School. It was here that his dreams of becoming a pilot were dashed. Whether it was aptitude or simply a pressing need for wireless operators, Bennett soon found himself closer to home at No. 2 Wireless School in Calgary, Alberta. Here, starting in July, 1943, he would spend a gruelling seven months learning the theory and application of wireless communications, signalling by flag and light as well as gunnery. Upon graduation, he could sew his Wireless Operator Trade Badge on his uniform.

Photos taken of Leading Aircraftman Kenneth Brian Bennett taken during his time at Air Observer School at Ancien Lorrette, Québec

Now a fully-qualified Wireless Operator, Bennett was selected for further training as a Navigator to make him ready to become part of a two-man Mosquito intruder team. For this, he was posted to No. 8 Air Observer School at RCAF Station Ancienne-Lorette outside of Quebec City to take another six-month course in air navigation and associated gunnery courses. Upon completion of the course and earning his navigator’s brevet, he was promoted to the rank of Pilot Officer. He was then required to attend a one-month course at No. 1 Aircrew Graduates Training School at RCAF Station Maitland, Nova Scotia, there to learn the duties and responsibilities he must now assume as an officer in the RCAF. At Maitland, he joined eight other recently graduated Pilot Officer navigators and 57 pilots of the same rank, all part of Course No. 18. Finally, after nearly two years in the RCAF, he was posted to an Operational Training Unit — No. 7 OTU at Debert, Nova Scotia.

Bennett (left) and two friends from No. 8 Air Observer School at Ancienne Lorette, Quebec pose in front of a statue of a mounted Joan of Arc on the Plains of Abraham in Quebec City while on a weekend pass from their studies. The airfield created at Ancienne Lorette for the purposes of training air crew, is now Jean Lesage International Airport (YQB). On his sleeve, Bennett wears his Leading Aircraftman propeller badge and above that, his Wireless Operator trade badge (a fist grasping three lightning bolts. The photo has an ‘X’ written over Bennett’s head, likely signifying his loss while in the RCAF. Photo: Bennett Family Collection, Ancestry.com

Crewing up

At Debert, two training streams—those of pilots and navigators—came together to create bonded two-man crews who knew how to fly and fight with the de Havilland Mosquito. Course No. 12 was assembled on October 9, 1944 and was comprised of 16 pilots and 15 navigators, half of whom were Royal Air Force airmen. The group was divided into two squads—Squad 1 was made up of RCAF men and Squad 2 of RAF men. After a few days of orientation and four weeks of ground school classroom work, Don Breadner was paired with a navigator by the name of Sergeant E. H. Smith and work began to build the two young men into an operational Mosquito crew, capable of long distance intruder operations into enemy territory. Breadner was rated very highly in every respect—his physical fitness put him second in the class, and he finished at the top of his ground school class.

A group photo of Breadner and Bennett’s Squad 1 on No. 12 Mosquito course at No. 31 Operational Training Unit, Debert. Donald Breadner is seated third from left and his Buffalo 33 navigator Brian Bennett stands at far left. Standing behind Breadner is Sergeant E. H. Smith, Breadner’s regular navigator. Judging by the greatcoats and gloves this photo was taken in October shortly after their arrival.

Buffalo 33

On the morning of November 30th Breadner showed up for the morning briefing to learn that his regular navigator, Sergeant Smith, was sick and that he would instead be paired with Brian Bennett who normally trained with Pilot Officer R. C. Hennessy. Flight Lieutenant Denis Owen Northcott, the Chief Gunnery Officer at No. 7 OTU, briefed and authorized Breadner and Bennett to carry out an aerial gunnery exercise, one which was very standardized and part of the Mosquito training syllabus. Also in the briefing was Flight Sergeant Jasieniuk, the pilot and sole occupant of the Bristol Bolingbroke aircraft that would act as the target for the exercise. Gunnery Exercise C.2, as it was called, consisted of four legs flown along a navigation line known as No. 1 Tow Line out over Cobequid Bay from the base — twice out as far as Economy Point and twice back. Exercise C.2 was Breadner and Bennett’s first gunnery exercise in the Mosquito and was designed to provide experience in gunnery range estimation. There were to be no deflection shots taken. The total duration of the day’s flight was to be one hour.

Northcott cautioned Breadner and the pilot of a second crew who were flying a similar C.2 profile on No. 2 Tow Line that all “attacks” on the target aircraft were to carried out with “zero boost”. Boost is positive pressure created by a turbo or supercharger. It forces more air into the engine. This can be matched with more fuel, to create a bigger bang inside the cylinders - resulting in more power. The pilots were to lay off the boost and make their approaches with a slower overtake speed which allowed more time to manoeuvre behind the target. On each of his attacks, Breadner was to fire a burst with his cine-gun at 250 yards astern, again at 200 and 150 yards. There were to be no live bullets, just a camera that captured the seconds of each burst. While the Mosquito had a radio, a radio compass and plenty of other equipment for flying blind, the Bolingbroke had none and was briefed to discontinue the line in the event of bad weather or malfunction.

The Mosquito and Bolingbroke pair detailed to fly a C.2 on No. 2 Tow Line ran into bad weather and used No. 3 Tow Line instead. Even on No. 3 Tow Line, the weather closed in and the crews scrubbed the exercise and returned to base. Northcott, upon debriefing the second crew, thought about recalling Buffalo 33, but since they were due back in only 10 minutes, he opted to let them finish up. Out over rainy Cobequid Bay and the hills of Cumberland County, Jasieniuk in the Bolingbroke pressed on with Breadner and Bennett closing in from behind again and again while the weather lowered.

A scene on the Debert flight line in 1943 with Hurricanes, Harvards and Anson of No. 123 Army Cooperation Training Squadron lined up for a parade. The Hurricane at right (RCAF 5636) was lost the month before Breadner and Bennett’s accident. During the attempted recovery following a high-speed dive, the outer half of the starboard wing was torn off due to a structural failure. The pilot, Flight Sergeant J.A. Holding, was killed. 123 Squadron would be renumbered 439 Squadron when it was transferred to Europe. Legendary 439 Squadron went on to operate Hawker Typhoons, F-86 Sabres, CF-104 Starfighters and CF-18 Hornets.

Mosquito KA114 was one of the aircraft assigned to No. 7 OTU at Debert in the time that Breadner and Bennett were there. It’s entirely possible that they flew this aircraft, which is one of the few Mossies that survive in flying condition today. Photo by Jack Zavitz, RCAF

According to Yarrow’s pilot, Sergeant Jasieniuk, both aircraft arrived at the waiting area five or six miles south of the airfield at the same time and commenced the C.2 Exercise immediately, flying at 3,000 feet. He also reported that on the first outward leg of the exercise, Breadner made seven or eight attacks, then the same number on the return leg, then again on the third. With each leg of the C.2 exercise, the two aircraft moved farther north until by the last leg, they were 10 miles inland from the north shore of Cobequid Bay. How Jasieniuk, who was the only occupant of the Bolingbroke could see and count the 25 or so attacks on his aircraft from his position in the cockpit was not explained, but it seems Breadner may have made a point of overtaking the Bolingbroke with each pass, before breaking off. In his accident investigation affidavit, Jasieniuk stated that the last time he saw Breadner and Bennett’s Mosquito was after the second and last attack on the fourth leg of the exercise when he caught sight of them 100 feet below and slightly ahead as they broke away in a diving turn to starboard.

KA114, restored to flying condition at Avspecs in Ardmore, New Zealand, now flies at Jerry Yagen’s Military Aviation Museum in Virginia Beach, Virginia. Photo: Richard Mallory Allnutt

The Bolingbroke pilot also stated that Breadner and Bennett did not seem to be in any sort of difficulty, but neither did they give the customary signal indicating that they had concluded the exercise and were returning. As Jasieniuk’s Bolingbroke was not equipped with any radio equipment, this likely would have been a waggle of the wings or something similar. They just broke off and did not resume their attacks. Jasieniuk then flew two complete turns to the right and then two the left looking for them. Confused, he had no way of communicating with either Breadner in Buffalo 33 or Debert Tower. He was still at 3,000 feet when he noted the time at 1015 hrs.

By this time, Jasieniuk was ten miles to the west of the western end of the tow line and 20 miles west of Debert. As he made for home, he could see that low cloud was pushing in from the southeast, settling down on the hills to the north and west of the airfield. He dropped down to 1200 feet looking for an opening, but seeing none, he opted for his alternate landing field at Scoudouc, New Brunswick 115 kilometres to the northeast. Heading in that direction, he pinpointed the town of Oxford, Nova Scotia which he circled for about 15 minutes while he consulted his map before setting course for Scoudouc. By the time he finally landed at Scoudouc, the cloud had lowered to just 700 feet.

Another surviving warbird from RCAF Station Debert is the Historic Aircraft Collection’s Hurricane XII (G-HURI), a former 123 Squadron Hurricane now in the markings of RAF 302 (Polish) Squadron. In September 2005 Hurricane Z5140 became the first Hurricane to return to the Mediterranean island of Malta since the Second World War. It flew there together with Spitfire BM597 as part of the Merlins over Malta project. Howard Cook was one of the Hurricane pilots of that project. In August 2012 she flew to Moscow to display in their centenary airshow. Photo: Howard Cook

At 1020, just before Jasieniuk began circling Oxford, 15 kilometres to the southeast along the old Intercolonial Railway line, a hardwood lumber inspector by the name of James McGibbon was overseeing the loading of sawn lumber at a railroad siding near the tiny community of Atkinson. He had climbed onto a stack of lumber which was being loaded onto railcars from a wooden platform along the siding and was standing nearly 14 feet in the air. While engaged in checking the wood for loading he happened to look up and notice, some seven miles to the southeast, a lone Mosquito aircraft flying from east to west in clear air above the leafless hilltops and below the cloud ceiling and coming directly toward the Atkinson siding where he was standing. There was nothing about the Mosquito’s approach that made him look up, he simply caught sight of it as he was looking around. Mosquitos flying about Cumberland County were daily occurrences in late 1944, so he thought not much of it.

At that moment, McGibbon’s attention was diverted by the approach of the Canadian National Railway’s Ocean Limited passenger train outbound from Halifax for Montreal. Thundering around the curve to the southeast, it passed Atkinson Siding at speed as it met the long down grade into Oxford. By the time he looked back up “a moment or two later” he saw a “big ball of fire” come from the plane which was still above the hilltops and a large cloud of black smoke out of which were falling “some pieces” which were not on fire. He estimated the Mosquito to be four miles distant when he saw the smoke and flame. He had witnessed the exact moment that Breadner and Bennett’s aircraft came apart. Two seconds later, they were gone.

McGibbon made these estimates of distances from his position not at the time but later during the investigation when he was asked to stand with investigators at the same spot while a Mosquito aircraft was flown on different vectors and at different altitudes so that McGibbon could match what he saw in his mind’s eye with what he could see in real time. Flight Lieutenant Henry Cobb, Inspector of Accidents for Eastern Air Command was standing with McGibbon at Atkinson Siding and estimated that Breadner and Bennett were at about 1,300 feet above sea level (ASL) at the time. Higgins Mountain, where they crashed, is itself only 1,100 feet ASL. The crash site was at about 1,000 feet ASL. It seems that Buffalo 33 and its crew were not much more than 300 feet above ground (AGL) when all hell broke loose.

A map depicting the relationship between Atkinson Siding, Higgins Mountain and Debert.

SIDEBAR: Debert’s station Medical Officer, Harold Henry Fireman, was from Ottawa, Ontario. As an young student doctor at the Ottawa Civic Hospital he was chosen to be the “intern in attendance“ at the birth of Princess Margriet of Holland. He joined the RCAF were he was a Medical Officer during the war with Eastern Air Command for four years. After a long and respected career he retired at age 88 and died in Ottawa in 2020 at the age of 101.

Just seconds before McGibbon witnessed the crash, a man named Leonard Lynds was working with his son in the bush at the top of Higgins Mountain. He heard an aircraft fly low over his position though he could not see it through the canopy. Seconds later the men heard two loud “backfires” followed two or three seconds later by a heavy explosion and then smoke rising through the trees about half a mile away.

Shortly after this, Debert Tower had begun calling the now overdue Buffalo 33 on the radio, but got no answer. Another Mosquito, flown by Flight Lieutenant J. R. Johnston with Gunnery Instructor Flying Officer G. Pothecary as spotter was despatched to search for the missing aircraft. They searched the area west of No. 1 Tow Line but saw nothing and heard no response from their own repeated radio calls. When Debert was finally notified by a call from the Westchester railway station that Buffalo 33 was down, a team was immediately despatched — including Debert’s Medical Officer Flight Lieutenant Harold Henry Fireman in the station ambulance and a guard detail to police the crash site. The time was 12:30, two hours after the crash.

Upon arriving at the scene with the aid of locals to guide him, Dr. Fireman saw only that “The aircraft and the bodies were completely shattered and pieces scattered over an area of roughly 1,000 square yards.” It must have been a grizzly and upsetting scene in the middle of the forest. The front section and fuselage were largely consumed by fire. Fireman grimly states: “Judging by the amount of skin and other parts found, there were definitely two bodies in the accident.” Only various small parts of the bodies were found, but he was able to identify the two airmen using a piece of Breadner’s scalp and a personal letter of Bennett’s found on the ground. As a testament to the absolute violence of the crash, when asked if he had taken samples of tissue or blood for a carbon monoxide test, Fireman answered flatly that “There were no tissues in a suitable state for a carbon-monoxide sample and no blood.”

Prior to the wreckage being found by the RCAF search party, there was “serious interference with the wreckage by unauthorized personnel”. It is not mentioned who these people were but likely locals coming to help and not scavengers. Two days later on Saturday, December 2nd, Flight Lieutenant Cobb, an Inspector of Accidents for Eastern Air Command arrived at the crash site and opened the official RCAF investigation into the crash. The crash site remained under guard during daylight hours for the remainder of the investigation.

Mosquito KB278 simultaneously lost both outer wing panels (shaded) and crashed at very low altitude with no chance of recovery.

Cobb determined that the aircraft had dived into the ground at an angle of 75 degrees on a due west heading, which differs from the original heading as witnessed by McGibbon (estimated by Cobb to be 330 degrees). Inspecting the trees, ground and distribution of the wreckage, he also determined that the Mosquito did not have its outer wings when it hit the north side of Higgins Mountain. The path through the tree tops, while short, was the width of the Mosquito from four feet outboard of the engine nacelles. Nearly all the shattered bits of the aircraft and its occupants were clustered in one confined area, yet parts of both wings outboard of the Merlins were found not in the main impact area but a bit father along the line of flight leading to the conclusion that they had detached at a point almost directly overhead of where the core of the Mosquito impacted.

Three weeks previous to the crash of Buffalo 33, Donald Wise (left) and his navigator Joe Grabowski were killed when the outer wings of their Mosquito broke off in a similar way. At the time, they had climbed to 25,000 feet and possibly were overcome by anoxia. The wings must have come off during a dive‚ intentional or otherwise.

Upon examining the structure, it appeared that the spars had failed upon “uploading” or high g-loading, usually occurring during an abrupt pull-up from a dive or similar manoeuvre. If it had not been for McGibbon’s testimony, Cobb “would have been inclined to think the accident resulted from just such a failure but the evidence of that witness refutes that possibility.” When asked if he thought that the two loud “backfires” heard by Leonard Lynds and his son “could have been the breaking of the mainplane”, he answered: “I think it most probable that the noises heard were due to the breaking of the wings.”

There was pressure from headquarters in Ottawa to proceed quickly and with absolute thoroughness not just because of Breadner’s father but also because there had been a recent crash of another Mosquito involving a similar structural failure. On November 4th, a few weeks before Breadner and Bennett’s crash, Mosquito KB173 attached to the newly numbered No. 8 OTU in Greenwood disintegrated in the air following a climb to 25,000 feet. It was not determined if anoxia was involved, but as the Mosquito dove towards the ground at high speed, the wings separated in the same locations as in the Breadner/Bennett crash. Flying Officer Donald Wise of Vancouver and Pilot Officer Joe Grabowski of Choiceland, Saskatchewan were killed. The RCAF was concerned there may be some sort of flaw in the wooden construction of the wings of the Mosquito aircraft built in Canada that caused it to come apart when stressed.

Investigators would later request that wing components and other parts be collected from Higgins Mountain, crated and shipped back to Ottawa for further analysis at the Forestry Products Laboratory. The close study looked microscopically at such esoteric things as tension flanges, webs, laminations, compression failure and grain slope. In time, it would be determined “that the condition of the timber in the main spars of this aircraft as revealed in the laboratory examination shows that the mainplane spars of this aircraft were below specification strength and this must be considered as a contributory cause of the accident.” The head of accident investigation for the RCAF, Group Captain F. S. Wilkins noted in his final report that:

As a matter of interest, it should be noted that the rate of failure of Mosquito Aircraft in the U.K. is approximately one in every 8,000 flying hours and similar results have been found in Canada. Most of these failures have occurred with pilots with little experience with Mosquitos. The last report on structural failure forwarded from the Air Ministry gave 16 such accidents in three months, five of these aircraft were Canadian built. This proportion is much too high, considering the relative output in Canada and the U.K..

Roughly 7,800 Mosquitos were produced in the Second World War with 1,000 built in Canada and 200 in the Australia. The above note from Wilkins uncovers a disturbing trend—while one in eight Mosquitos were built in Canada, one in three structural failures covered in the report involved Canadian-built Mosquitos.

But all this was in the future.

Immediately following the crash and the determination that Breadner and Bennett had not survived, came the unpleasant duty to notify the parents of both men, collect their remains and send them home to their families. In the case of Donald Breadner, the responsibility for notifying the Air Marshal that his son was killed must have been a trepidatious duty indeed. Without knowing the circumstances of the accident that took their lives, Wing Commander Robert “Moose” Fumerton, No. 7 OTU’s commanding officer must have dreaded the scrutiny lay ahead.

A telegram was delivered to Allie and Nel Bennett on their family farm near Raymond, Alberta and Lloyd Breadner was cabled at RCAF headquarters in London, England. Three years earlier, it was Breadner who had lobbied the Canadian government and the Royal Air Force to establish Operational Training Units on Canadian soil. The tragic irony of his son’s death at one of these OTUs was likely not lost on the Air Marshal.

By this time, the story of their fate was published across the country, primarily as a story about Air Marshal Lloyd Breadner’s son being killed in training. It’s understandable that Donald would be the focus of any reporting, but Brian Bennett was always an afterthought in any newspaper clipping I read in my research. Bennett was always mentioned in the final paragraph of these stories and always referred to as “the other airman” or “also killed” before being named — even in Alberta newspapers.

The Funerals

If your son or daughter died overseas in the service of the armed forces of Canada during the Second World War, there was no shipping home of the body as we expect today. No poignant last ride down the Highway of Heroes with bridges lined with appreciative Canadians. In fact, most mothers and fathers whose sons died in battle from Hong Kong to Holland, would never even get a chance to visit the graveyards where they were buried. There was no “closure” as we call it today, the chance to watch a casket lowered into the frozen ground of Canada, to stand before a headstone and weep, no proof of death other than a telegram, a letter and a flocked box with a Memorial Cross lying in satin. It was a very hard pill to swallow. Historian Pat Sullivan, in Legion magazine, wrote that Canada’s long-standing “buried where they fall” policy, which followed the lead of the British Army in 1915, lasted through both World Wars and Korea all the way to 1970. In fact the first Canadians killed in active combat on foreign land who were immediately shipped back to Canada for burial or cremation were four members of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry who, after being killed by “friendly fire” were flown home from Afghanistan in 2002. Prior to that, the only Canadian soldier who made it home (an unidentified First World War soldier 85 years after his death) now lies within the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Ottawa. Other than the Unknown Soldier and the dead of the Afghan war, Canadians who died on active service can be found in the soil of 74 other countries around the world.

If, however, your son died while on duty in Canada or even North America during the war, his remains, whether they were whole or partial, were placed in a casket and, following a local military ceremony, were returned to you for final burial. This of course did not apply to servicemen of a foreign country who died on Canadian soil. The remains of Canadians usually made the journey in the baggage car of a train or in the case of shorter distances, the back of a lorry. When 21 veteran RCAF pilots and an airman were killed in Estevan, Saskatchewan in 1946 in the second worst flying accident in RCAF history, all but one man were carried home by train. The exception was Flight Lieutenant Harry Cowan, DFC. His casket went by air so that it might arrive in time for his dying mother to see. She rallied long enough to attend his funeral and then she too passed away.

Today’s military funeral is precisely prescribed in every detail in Chapter 11 of the Canadian Armed Forces Manual of Drill and Ceremony which outlines at length the specifics of the procession, strength of funeral party, escort, guard, band, bearer party, headdress bearer, pall bearers, chief mourners, King’s representative, mourners in and out of uniform, church seating plans, graveside service etc. For instance, it is specifically written that the Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) will have a 400-strong escort led by a Colonel, a 50-member ceremonial guard led by a Captain, a bearer party of eight Chief Warrant Officers led by a ninth, 8 honorary pallbearers and a rear detachment of 50 led by another Captain. At the bottom end of the funeral escort continuum, a deceased Sergeant or lower is entitled to an escort of only 20 service men or women led by a Sergeant, a 12-member guard led by a Sergeant and a bearer party of 8 Sergeants or below led by a Sergeant. In all, the CDS is officially entitled to 516 service personnel at his funeral, while a sergeant is entitled to 40.

The meagre remains of Breadner and Bennett were enfolded in Royal Canadian Air Force ensigns and placed in their caskets which were then permanently sealed. There would be no open casket service. A brief military funeral service, conducted by Honorary Flight Lieutenant Rev. E. R. Woodside, was held at the Mattatall Funeral Home in the town of Truro, Nova Scotia. Following this, an escort comprised of 12 officers as pall bearers, 12 officers as the funeral party, a firing party of twelve airmen, two trumpeters and a 31-man escort accompanied the caskets to the Truro train station where they were loaded into the mail car of the Ocean Limited on December 3 to begin their long journeys home — 1300 kilometres for Breadner, 4,650 kilometres for Brian Bennett. Two pilots from No. 7 OTU accompanied the caskets to their homes. Pilot Officer Owen Maynard, a course mate of Breadner’s and Bennett’s rode as far as Montreal and switched trains for Ottawa with Breadner’s casket. Flying Officer John Caine rode from Montreal with Bennett’s remains to Alberta, where he too was from. Flying Officer “Johnny” Caine, DFC and Two Bars, was an experienced Mosquito intruder ace who was back in Canada as an instructor at Debert. He would return to Europe in March, 1945 and end the war with 5 aerial victories and 15 aircraft destroyed on the ground and 7 on the water and three Distinguished flying Crosses. Maynard, of Sarnia, Ontario went on to a stellar career as an aeronautical engineer working on the Avro Arrow and then went on to NASA following the demise of the Arrow. At NASA he became the lead designer for the Lunar Module and then Chief of the Systems Engineering Division in the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office and then Chief of the Mission Operations Division. He presided over two lunar landings and take-offs and then went to work for Raytheon Corporation. Bennett and Breadner were well escorted indeed.

Breadner and Bennett were both accorded military funerals in their home towns, and as serving airmen of the very same rank, they were entitled to similar services. They were not quite the same however. Of course this difference would be for two reasons. Firstly, the nearest Canadian military facility to Raymond, Alberta was 20 miles away in Lethbridge while Breadner’s Ottawa was the bustling epicentre of Canada’s wartime leadership with streets awash in uniforms of all types and ranks including men and women of Canada’s allies. Secondly, Bennett was a humble farmer’s son while Breadner’s father worked with the likes of Lord Louis Mountbatten, “Hap” Arnold, George C. Marshall and Billy Bishop. The funerals were both solemn, military spectacles befitting the sacrifice made by both men but Breadner’s service stands out because of those who attended it.

After arriving at Ottawa’s Union Station late Sunday evening, December 3, Breadner’s casket was likely met by his mother, local family members and staff from George H. Rogers Limited, a funeral home on Elgin Street directly across from RCAF headquarters in the Temporary Buildings. The funeral home was no more than a few hundred yards from the station. Meanwhile, ever since the confirmation of Breadner’s death, arrangements were being made to not only honour young Donald, but also the sacrifice of his father.

The intimate service itself, held two days later in the parlours of the funeral home, was conducted by an air force chaplain, but not just any chaplain—Air Commodore, the Rev. William Ewart Cockram, a First World War fighter pilot, the RCAF’s first appointed chaplain and Director of the RCAF’s Chaplain Service. As Breadner was a Christian Scientist, Cockram was assisted by Reverend D. Christie of First Church of Christ, Scientist. Seated in the chapel were a number of Ottawa’s and Canada’s most notable wartime leaders. Perhaps the most legendary figure of all in Canada’s aviation history — J. A. D. McCurdy, Canada’s first pilot — was in attendance. There were two Air Marshals — family friends and Great War fighter pilots Billy Bishop and Bob Leckie. There were seven Air Vice Marshals including Gus Edwards and William Curtis. Although it did not exist at the time, McCurdy, Bishop, Leckie, Edwards and Curtis were all to become inducted members of Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame. On the political side, there were three War Cabinet Ministers seated in the pews — Navy Minister Angus Macdonald, Deputy Minister for Air H. F. Gordon and former Minister of Defence James Ralston. Also noted among the seated were three Air Commodores, seven Group Captains, nine Wing Commanders, two Squadron Leaders, two Major Generals, three Brigadier Generals, four Colonels, six Lieutenant Colonels, one Admiral, one Sheriff and Stanley Lewis, the Mayor of Ottawa. Among the many uniformed officers were also the military attachés of the United States, Australia, Poland and Czechoslovakia.

As the casket was carried by the pall bearers down the steps of the funeral home to a waiting RCAF flatbed truck on that clear, cold December afternoon, hundreds of men and women in uniform and in civilian dress lined the street on both sides. The 50-piece RCAF Central Band raised their instruments and played Nearer My God to Thee and the Dead March from Handel’s oratorio Saul which is played at state funerals like those of Horatio Nelson, the Duke of Wellington and twenty years in the future, that of Winston Churchill. The procession moved north along Elgin, winding its way towards New Edinburgh and eventually Beechwood Cemetery. The procession, led by a large escort party, followed in order by the band with muffled drums and muted instruments, a funeral guard of six Flight Lieutenants, the Reverends Cockram and Christie, a bearer party of six Aircraftmen, a headdress bearer with Breadner’s cap and then the many mourners including Donald’s mother, grandparents and sisters as well as Billy Bishop and Gus Edwards who walked all the way to Beechwood for the internment.

As strange as it may seem, the one person who was not in attendance on that early winter day was Air Marshal Lloyd Breadner himself. He asked his old friend Air Marshal Gus Edwards to stand in for him. Breadner had been in London for several months, and though he could easily have commandeered an aircraft to take him home for his son’s funeral, he chose to stay and continue leading the RCAF overseas. No other serving officer or airman in a war zone was allowed to return home to attend a family funeral, so Breadner chose to keep to a single standard and suffer his son’s loss at his desk, carrying out his duty like all the men and women under him. Such was leadership in those times.

As big an undertaking as young Breadner’s funeral was, there exists no photographs of the event on the internet or in the newspaper records. No doubt there was an official RCAF photographer there to record the “who’s-who” of the RCAF leadership and procession for the benefit Air Marshal Breadner in London. If these exist somewhere in the Library and Archives of Canada, I would love to know.

Solid Brass! There were several hundred mourners who attended the funeral of young Donald Breadner, demonstrating the respect that Canadian military leadership had for his father. Some of the Canadian war leaders who walked in the procession included (left to right top row): Air Marshal William Avery Bishop, VC, CB, DSO & Bar, MC, DFC, ED, Canadian First world war ace and , Angus Lewis Macdonald PC QC, First World war veteran, former Premier of Nova Scotia and federal war cabinet minister responsible for the navy; James Layton Ralston PC, CMG, DSO, KC, First World War Veteran and former Minister of National Defence; Air Marshal Robert Leckie, CB, DSO, DSC, DFC, CD, First World War Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) pilot, and officer overseeing the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan on Canada; Second Row: Air Vice-Marshal Adelard Raymond, CBE, ED, Air officer commanding (AOC) No. 1 Air Command; Air Marshal Wilfred Austin Curtis, OC, CB, CBE, DSC & Bar, ED, CD, RNAS fighter pilot in the First World War, Member of the Air Council; Air Vice Marshal George Roberts Howsam, CB, MC, First World War fighter ace and Director of Training for the RCAF. Honorary Air Commodore The Reverend William Ewart Cockram, First World War pilot and Principal Chaplain (Protestant) of the RCAF. Lieutenant General Maurice Arthur Pope CB MC, Veteran of the First World War and Vice-chief of the general staff in Ottawa, Chairman of the Canadian Joint Staff Mission in Washington, head of the Censorship Branch and military staff officer to Prime Minister Mackenzie King. Legendary John Alexander Douglas McCurdy MBE, Canada’s first pilot and Assistant Director General of Aircraft Production; Air Marshal Harold "Gus" Edwards (Ret’d), CB, First World War pilot, PoW, escaper, Air Member for Personnel at RCAF Headquarters, and recent AOC-in-Chief RCAF Overseas and Ottawa Mayor J. E. Stanley Lewis of Ottawa. Billy Bishop, J. A. D. McCurdy, Robert Leckie, Wilfred Curtis, and Harold “Gus” Edwards are all members of Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame

Though young Donald Breadner is always written up as a Pilot Officer in the No. 7 OTU Operations Record Book and subsequent accident investigation, ha actually died a Flying Officer. His promotion to Temporary Flying Officer (TFO) had been granted in September, 1944, and the promotion finally came though shortly after his death. The same applied to Bennett. Unit records and newspapers of the day reported them both a Pilot Officers, but they were in fact Flying Officers.

As Donald Breadner’s flag-draped casket moved slowly through the city, those lining the streets could imagine a young, vibrant man laid out in his blue uniform within the darkness of the box, eyes gently closed and hands peacefully crossed. In reality, it contained something more like a packet from the butcher. The elegance and martial tradition of the scene, the slow cadence of respect and the muffled drumbeat of his passing provided mourners with a welcome lens which filtered out the obscenities of war. Breadner was buried in the family plot at Beechwood Cemetery. At first, his grave was marked by a simple wooden cross with his name and rank and later, after the winter, by a simple granite headstone of the type that marks the resting place of most men and women who died in the service of a Commonwealth country.

After the war, Lloyd and Elva moved to a leafy crescent in the Glebe neighbourhood of Ottawa near the Rideau Canal. He retired as an Air Chief Marshal and at the behest of the RCAF helped create the RCAF Association, serving as the association’s first president. His health had been declining for a few years, his body worn and bloated from the pressures and sedentary lifestyle of senior command. In the winter of 1951-52, suffering from dangerously high blood pressure, he was ordered by his air force physician to spend the rest of the winter in the warmth of Florida. While he was there, his old friend Gus Edwards who had stood in for him at his son’s funeral, died suddenly in his sleep in Scottsdale, Arizona and was buried in Beechwood a week after. Two weeks later, in Florida, Lloyd Breadner suffered a stroke. The RCAF sent an aircraft to bring him back to Canada, but on the return flight, his condition worsened and the aircraft made an emergency landing in Boston. He died in a Boston hospital with his wife at his side a short time later. He was just 57 years old.

Breadner’s obituaries in both the Ottawa Citizen and Journal were front page stories and detailed much of his very accomplished life. They came out within 24 hours of his death, so had obviously been written in advance. A couple of days later in the editorial section of the Ottawa Citizen, the editors wrote:

“Within a few weeks of each other, Canada has lost two distinguished airmen who helped forge one of the most formidable striking weapons this country has ever possessed. the death of Air Marshal Harold Edwards has now been followed by that of Air Chief Marshal L. S. Breadner. the careers of these two men, neither of whom reached the age of 60, present a remarkably close parallel from the days when they were both combat fliers with the Royal Naval Air Service in the First World War.

Air Chief Marshal Breadner will be remembered in the history of these times, as one of the architects of the [British] Commonwealth Air Training Plan. There could be no finer memorial than this. For under this cooperative scheme, more than 131,000 young men from Canada, Britain, Australia and New Zealand received air crew training at schools in all parts of Canada. There is no question that the [British] Commonwealth Air Training Plan was vital to the outcome of the war

Canada may count itself fortunate that, when the test comes, it can produce men who have the imagination as well as the technical equipment to rise to the occasion. Lloyd Breadner was one of these, as was also “Gus” Edwards, his colleague in war and peace for so many years.”

His funeral was as elaborate as that of his son, which was his due, with mourners from military and civilian life lining the parade route along Laurier Avenue and north along Charlotte Street to Beechwood. The honorary pall bearers included seven Air Vice Marshals and one Group Captain. As grand as his funeral was, Lloyd Breadner chose to be buried next to his son under a simple wartime headstone. While he could not be there for his son’s funeral, he chose to lie with him for eternity.

Lloyd Breadner requested a simple military headstone similar to that of his son Donald and was buried alongside him in 1952.

Bennett’s funeral

While Owen Maynard switched trains in Montreal for Ottawa with Breadner’s remains, Flying Officer Caine with Bennett’s casket carried on across the country over the north shore of Huron and Superior, across northwest Ontario’s lakes and forests, driving out onto the prairies of Manitoba and the ocean-like surface of Saskatchewan to Southern Alberta, arriving home four days later on December 7th. Breadner had already been in the ground two days by the time his navigator finally arrived home on that cold Alberta day. It had been a long and gruelling voyage for Caine, but he still had a duty to carry out.

It had been a week since Bennett’s family had received news and they had had time to gather and prepare. In Raymond, everyone knew someone from the large and “well known pioneer family of the south” and there was plenty of help to make arrangements. It was not possible for me to find a newspaper clipping that reported on Brian Bennett’s funeral, though there must have been one. Digital records of small Southern Alberta town newspapers are sparse indeed. However, the family has shared photos of the funerals on Ancestry.com and these help to take us back to that day.

It was a cold and clear winter’s afternoon on the southern prairie when the funeral party emerged from the whitewashed art-deco “First Ward and Taylor Stake” Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter Day Saints in Raymond, Alberta. The sun was low on the southern horizon as Bennett’s brother Stanley, accompanied by Flying Officer Caine led the casket to the waiting hearse at the corner of Church and 200 Street. Once the casket was transferred, the procession, which included around 100 officers and airmen from a nearby RCAF base, Allie and Nel, their daughters and sons, and church friends, moved slowly eastward on Church Avenue and then, two blocks later, wheeled north on Broadway Street. They continued on slowly through the business section of town, wheeled right on Railway Avenue and out onto the Mormon prairie towards Temple Hill Cemetery, some three kilometres from the centre of town — a long dark line of men and women, silent save for the tramp and shuffle of boots and the muffled beat of the drum. With the sun lower on the southern horizon, long shadows preceded them at funeral cadence past Factory Lake and the massive red brick Knight Sugar Factory, where a heated river of sunlit white vapour rose vertically from the smoke stack to the heavens.

At the graveside, a lone bugler played the Last Post and the firing party presented their rifles and barked three times into the cold prairie air. Bennett’s sisters flinched with each volley. The sun was low on the horizon and the scene bathed in warm light as Brian Bennett’s remains were lowered into the dark earth of the land his family had farmed for decades.

Stan Bennett with Flying Officer John Caine ahead of the Union Jack-draped casket emerges from Raymond’s Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints after the funeral for his little brother Brian on December 8, 1944. The Bennetts were a large, hard working and close-knit family and the pain of the loss of his brother can be seen on Stanley’s face. Family photo via Ancestry.com

A hundred or so airmen were bussed in for Brian Bennett’s funeral, likely from a nearby base in Southern Alberta such as Lethbridge or Fort MacLeod. At left, the funeral procession makes its way to Raymond’s Temple Hill Cemetery over new fallen snow on Church Avenue. I cannot be certain, but the officer standing before Bennett’s draped casket at right appears to be Flying Officer Johnny Caine, the man who accompanied the casket all the way from Nova Scotia by train. Family photos via Ancestry.com

At right, officers wearing black arm bands salute and the honor guard presents arms while the bugler sounds the Last Post. The large quantity of flowers demonstrates how much respect there was for the Bennett family in Raymond. Family photo via Ancestry.com

Aftermath