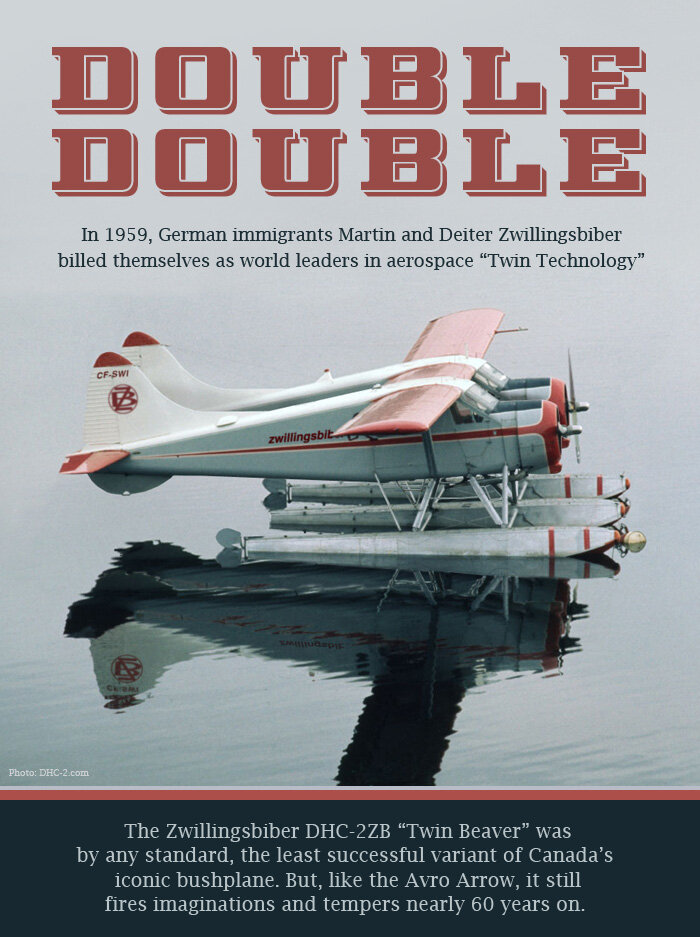

THE PINK AND THE BLACK

Warning: April Fools Spoof originally posted in 2009

This year marks the 100th anniversary of powered flight in Canada and across this broad nation everyone joins the celebration with great joy and excitement. Well, not everyone. April 1, also marks the 85th anniversary of the founding of the Royal Canadian Air Force, the progenitor of today’s modern Canadian Air Force. No doubt, everyone who ever donned a blue tunic with wings will be celebrating this double celebration. Well, not exactly everyone.

This day also marks the 60th year since the former Dominion of Newfoundland, chose (or rather voted) to forfeit its status as an independent country within the British Commonwealth and join the confederation of provinces to the west known as Canada. And on that very day, while Canadians celebrated in Ottawa, and pro-Confederation Newfoundlanders danced in the streets of St. John's, the once glorious, valourous and honoured Royal Newfoundland Air Force stood down from military operations, grounded all aircraft and ceased to exist. RNAF airmen headed to messes from Goose Bay to Argentia to drown their sorrows and quell their anger. In somber ceremonies from Avalon to Nain, while pipers played the mournful notes of Squid Jiggin’ Ground, tearful airmen hauled down the famous “Pink” – the RNAF’s proud ensign under which so many had fought, shed blood and died. It was not a happy day by any stretch of the imagination. For the men and women who wore the pink cuff bands of the RNAF, it would be forever known as Black Friday.

The almost mythic warrior legacy of the RNAF went back only thirty years, but oh what a story they wrote with their derring-do and vapour trails in the skies from Cape Chidley to Pas de Calias, from Ceylon to Carbonear, from Malta to Come By Chance. Of all the “Royal” air forces, the smallest was that of Newfoundland, but this little force suffered the highest of casualty rates (1 in 4 dead or wounded in the Second World War), volunteered for the most difficult missions and wreaked the most havoc on the enemy in terms of aircraft destroyed per operational aircrew. The “Newfs” or “Coddies” as they were called, were outwardly scoffed at because of their size but secretly admired by other Allied airmen. But that was the Second World War. We are getting ahead of the story of the finest little air force that ever tore into battle. Let’s go back to the beginning.

When the Germans signed the Armistice on November 11th, 1918 the War to End All Wars came to a formal close. Germany’s economy and even its social order were in shambles. But unlike the Second World War, its factories and industrial might were somewhat intact. At Fokker’s assembly plant in the city of Schwerin in the northern state of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania, unpaid factory workers had largely abandoned their lathes and drill presses in the search for food. The factory was left unguarded. It happened that, in early December, a small patrol of the Newfoundland Regiment, led by a former fisherman from Witless Bay named Captain Cecil Purdy, had just entered the factory district of the small city as part of a short term occupation and reconnaissance to assure the Allied high command that war production had ceased – much like the Open Skies of today.

At the outset of the war, Purdy, or “Jigger” as he was called by fellow officers, was a Lieutenant in the 1st Battalion, Newfoundland Regiment – the legendary Blue Puttees, a name which came from the colour of their puttees – the long cloth strips wrapped tightly around the lower legs. This tall, hard-boned and somewhat quiet man had survived the disastrous assault at Beaumont-Hamel during the Battle of the Somme and had had enough. He moved up from the meat-grinder that was trench war to become only the fifth Newfoundland-born fighter pilot in the Royal Flying Corps. Purdy, flew with both abandon and distinction for the next two years, claiming 4 victories in the air. Whether he thought of them as a good luck talisman or a daily memorial for fallen comrades, and though he angered haughty British commanding officers, he steadfastly refused to remove his Blue Puttees for the rest of his career. Despite his rebellious attitude, his actions in the air gained him a promotion and a whole lot of respect. He had a reputation for victories in the boudoirs of Paris too, and he soon grew to love his time in Europe. When he was demobbed from the RFC, he was not yet ready for the cold, fog and wet of Witless Bay, so he volunteered to rejoin the Blue Puttees to conduct mopping-up operations and then Armistice compliance patrols such as the one that brought him to Schwerin.

The Fokker factory at Schwerin was still in full production at war's end, but with the collapse of the country's economy, its highly skilled workers with nothing to build and no one to pay them, left the facility to it's own devices. Captain Cecil Purdy (inset) would chance upon the factory and its treasures, and see in them the opportunity to build an air force. Photo: Fokker Archives and Purdy Family Archive

On that December morning, following orders, he and his company entered the Fokker factory that, until a week or so before, had been under the control of German aircraft production – the Kogenluft (Kommandierenden General der Luftstreitkräfte). In a massive storage hangar near the runway and hidden beneath camouflage netting, he came across a sight that, for a fighter pilot, was a breathtaking opportunity – 24 brand new, factory fresh, Fokker Dr-1 Driedecker Triplanes covered in white tarpaulins. The compact little tri-plane was of the same basic type made famous by Baron Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron. In April of 1918, Richthofen was in fact, shot down in just such a craft - by the combined efforts of a Canadian pilot and Australian gunners.

He had his men drag the covers off the ones most accessible and by the fourth, he had come upon an idea. A very daring idea to say the least. This brilliant concept, though bordering on looting, would be the moment of conception for the Royal Newfoundland Air Force. Over the next three weeks, Purdy negotiated with factory employees to trade some Allied food supplies for 18 of the 24 fighters, disassembled and crated them, then commandeered 25 British Army trucks (7 trucks were filled with parts and ammunition for the guns) and loaded them with the crates. Schwerin was only 50 miles from Hamburg, Germany’s second largest city and its largest port. And this is where it all started to fit together.

Purdy’s older brother Cedric, a highly skilled fishing captain out of Witless Bay, had joined the merchant navy at the first sign of hostilities in 1914. He had survived four years of North Atlantic convoy runs and two sinkings by U-Boat torpedoes. He had worked his way from Second Mate to Captain and towards the end of the war was often chosen as Flotilla Commodore for the convoys he participated in. His ship, the SS Laconic, a 7,000-ton general cargo ship of the Chimo Shipping Lines, was tied up at Hamburg’s Landungsbrücken jetty after delivering wheat and other foodstuffs from Canada. Captain Purdy was under orders upon unloading to return the ship to her homeport of St. John's, Newfoundland – with haste. There wasn’t much time.

On the night of January 14th 1919, while rain and sleet poured down in sheets across the Landungsbruken, 25 Army trucks pulled up alongside the rusting freighter. At first light, the loading was complete, and Laconic’s crew let go all lines, and with the unwitting aid of a German harbour tug, slipped into the Noderelbe Channel, and made her way to the open sea. Like a pregnant whale, she carried in her belly 18 baby aircraft, that would in just a few short months, become the nucleus of the Royal Newfoundland Air Force.

Ironically, the steamship SS Laconic commanded by Captain Cedric Purdy would be the birth mother of one of the greatest air forces ever. Photo: Chimo Shipping Archives

Related Stories

Click on image

Purdy was a staunch supporter of Newfoundland’s independence – a passion possibly spurred by the needless slaughter of so many of his fellow countrymen in the trenches while under the disdainful command of the British Army. Purdy was convinced that, lying next to Canada (which itself had come to the same conclusions about independence), Newfoundland was a prime target for annexation. With the dominance of air power a lesson he learned well on the Western Front, Purdy chose a course of preemptive arms. He could easily imagine swarms of Canadian Sopwiths crossing the Straits of Belle Isle and descending upon his homeland to force her into a confederacy. This paranoia, in many ways, would lead to the events of 1949. But again we are getting ahead of ourselves.

By the April of 1919, the Newfoundland government had passed into law the formation of the Newfoundland Flying Corps – a full five years before Canada had its own independent force. As its first commander, the nascent NFC selected Purdy himself, now promoted General of the Corps – the Commonwealth’s youngest at age 31. His first task was to choose colours, a flag, roundels and uniforms for the 100 or so new recruits. Being a xenophobic pro-islander, he selected the Pink, White and Green Tricolour of what islanders called The Native Flag, Newfoundland’s first. Pink was now the colour of rebellion, courage and of self-determination.

During the spring and summer of 1919, Purdy worked at St. John's Lester's Field, meeting and recruiting men and officers, organizing, lobbying for funds and overseeing the building of the force. It was at Lester's Field that he met Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten Brown as they waited for good weather to make their bid to cross the Atlantic by air. Purdy toured them through the construction projects at Lester's and was given much encouragement for his endeavour. In return, Purdy contacted many of his fishermen associates to get the gen on weather conditions over the first 500 miles of their course. When they arrived in Ireland, the two adventurers held a press conference where they thanked the Newfoundland Flying Corps for their assistance - the very first time the NFC was talked about in public.

It took nearly 6 months, but the 18 Fokkers were eventually uncrated, painted and re-assembled to form the core of one of the finest little air forces the world has ever known. But the little Fokkers were a handful for new pilots to contend with and a training program was quickly put into place. The first squadron of operational fighters, the Cod in the Ring boys, was made up from experienced scout and fighter pilots from the war. They were ready to fight at the end of the summer of 1919. From its war reparations beginning, the NFC grew into an efficient, albeit small fighting force that prided itself on being lean and mean.

The Fokker Cr. 1 Driedecker was an unlikely start for a fighter wing of an Allied air force, but they served the RNAF well until replaced by British-built Derby Dingbats in 1926. The Cod in the Ring squadron had 18 fighters - all named for towns in France where the Blue Puttees had fought. Duncan Kelligrew of No. 2 squadron would go on to command the unit (On Spitfires) in the Second World War. He was killed in action in 1941. Illustration: D.H. Yellamo

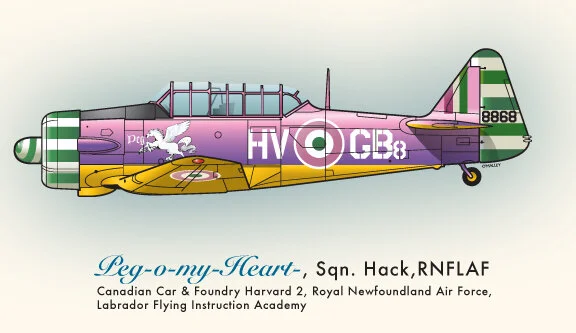

Between the wars, the little air-force-that-could honed its organizational and flying skills and on April 1st, 1923, a full year before Canada, changed its name to the Royal Newfoundland Air Force. By 1939 the RNAF operated two squadrons of fighters (No. 1 - The Cod in the Ring Squadron and No. 2 The Blue Puttees), one maritime/coastal patrol squadron (No. 103), two transport squadrons (No. 700 and 702) and one large training base at Goose Bay/Happy Valley in Labrador – The Labrador Flying Instruction Academy. Today, the Canadian Air force still Operates 103 Search and Rescue Squadron out of Gander, Newfoundland – the last link to the RNAF.

A/M “Jigger” Purdy was eventually promoted to Marshal of the Air Force and remained in command of the force until 1938, when he was killed in a tragic kitchen party accident. A bottle of screech, left on a hot coal stove by a thoughtless cousin, exploded killing both Cedric and Cecil. But the Marshal’s vitriolic independence and anti-confederacy thoughts had permeated the ranks of “Purdy’s Little Fokkers”. The Royal Newfoundland Air Force became the symbol of pride for this young dominion, and recruitment was high and morale even higher.

The Second World War would affect the people of Newfoundland greatly. Many of the youngest and most courageous of islanders would join the Merchant Marine and risked death working the dangerous North Atlantic convoys. Many would pay the price. But the war represented the golden days of the RNAF as well. Pilots, aircrew and maintainers of the RNAF would blaze a trail of glory from Ceylon to Iceland and their country's pride in them made them heroes at home. Colourful collector cards featuring the pilots and their exploits were offered in each pouch of Barrelman's Delicious Dulce (a salty kelp snack) and box of Captain Crummie's Cod Flakes 'n Cranberries. The RNAF Central Band, the only military marching band in the Commonwealth to feature the fiddle, spoons and the squeezebox, was in constant demand for parades and fleet blessings.

By 1940, No.s 1 and 2 Squadrons were shipped to England where they transitioned to the Supermarine Spitfire V, VII and XVI. Throughout the war, the men of the Blue Puttees and Cod in the Ring would take on all comers - both the enemy in the air and any "fancy boys" on the ground who put on colonial master airs. RNAF pilots fought from the Battle of France to war's end and never looked back until their work was done. A young man from Dildo, Newfoundland named Walter Snook began the war as a young Squadron Leader and ended as a Group Captain and an ace. Walter's legendary Race to Malta is well known by every Newfoundlander and even Canadian school child.

Snook would return to Newfoundland after the war and within 2 years, was Air Commodore and acting Commander of the RNAF. At the time of Confederation, he had risen to Air Marshal and was in control of a small force that had fought fiercely for Newfoundland and for its independence.

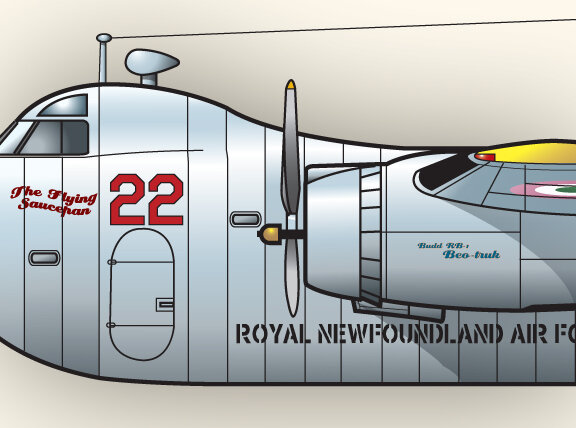

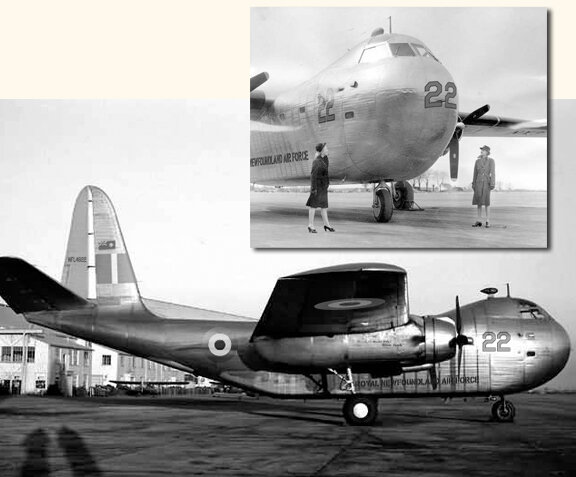

While the fighter boys were off making a name for themselves in places distant and foreign, the aircrews of the newly formed "Maritime Command" of the RNAF became the face of war and defiance at home and everyone knew their names. Pliots like F/S Bensen Curlew, P/O Maurice "Lord" Hawe, and P/O Percy "Eyeball" Pomeroy were known by sight in any town or village on the Rock. Sailors and fishermen always knew they would be rescued if they remembered the saying "Just sit tight where you are till dey gets where yer at". Of course, the RNAF, being comprised of seafaring men, rarely took their aircraft out of the water except for an occasional barnacle scraping - old ways die hard. Air Force wags called the little used land-sea capabilities "amphibiguous".

Newfoundlanders and convoy sailors could not only count on being rescued by 103 Squadron's collection of flying boats and amphibians, they knew that they would be hunting down U-boats all the way to the tail of the Grand Banks and sometimes to mid-ocean. There was a saying of the day - "When the flying boats are up, dem U-boats are way down". And a popular song of the day in Newfoundland, sung to the tune of "I's da B'y" went something like this:

I's da b'y dat looks fer boats

An' I's da b'y dat finds 'em

An' I's da b'y dat scares 'em good

An' paddles dere behinds den

At the very end of the war in February, 1945, a U-Boat reportedly carrying Nazi henchman Martin Bormann was detected in shallow water in Placentia Bay off the coast of Argentia. The submarine was hounded for six hours and driven off. Later, the captain of the U-Boat admitted that they had misread the Enigma coded message ordering them to Argentina. By the end of the war, aircraft of 103 Squadron had sunk 7 confirmed and 4 probable U-Boats and rescued thousands of shipwrecked airmen. 103 became such a golden thread of the fabric of this small nation, that a clause was added uncontested to The Newfoundland Act, 1949 and Terms of Union of Newfoundland with Canada that stipulated that 103 Sqaudron would continue to exist after the RCAF took command of personnel and assets of the RNAF. To this very day, 103 Rescue Unit still flies Search and Rescue missions from Gander, Newfoundland, continuing the legacy started by the RNAF.

From the end of the war until 1949, the Royal Newfoundland Air Force enjoyed superstar status across the country from the Quebec border to the Avalon Peninsula, but trouble was brewing under the bravado. A firebrand and insidious journalist by the name of Joey Smallwood was whipping the population up into a lather of Confederation with Canada - playing on the post-war economic downturn and convincing more and more people that the little island country couldn't make it with out help. This was anathema to the RNAF which was founded on the very concept of going it alone.

Led by A/C Walter Snook (eventually A/M), the air force did something no air force in the world would think of doing - they became a virtual political party, organizing rallies under the pretext of air shows, putting forth electoral candidates from the ranks, flying pro-republican speakers where ever they needed to go, towing banners over St John's with the slogans like - "Confederation is Capitulation", "If you can't beat em, try again", "Confederation- the Arse is out of 'er Now" and "It will be a Large Day in Hell". They soon felt the wrath of Smallwood who wrote vitriolic and slanderous columns from the safety of his newsroom typewriter. For a valorous and faithful fighting force like the RNAF who had just recently returned from a war that saw excessive casualty rates, being called treasonous was almost too much to take. Snook was rumoured to have said at a mess dinner that he rued "the day we decided not to get into the bomber business" referring to a pre-war decision to operate only defensive and transport aircraft. The words were taken (rightly so) by Smallwood and his retinue as a veiled threat.

But Smallwood needn't worry about Snook and his Royal Newfoundlanders. They were strong willed, but they had the interests of Newfoundland at heart. All-out civil war or a military coup was never a consideration. But, a little protest was not out of the question. When Black Friday came, and the RNAF ceased to exist, Snook was ordered to change the roundels on all aircraft of the RNAF. The order came with the assumption that Snook would know what roundels to replace the Pinks with - the RCAF's. But since they were not specifically mentioned, Snook designed and had painted a black circle with a white "X" in its centre on the six DC-3 Dakotas of 702 Squadron - the aircraft that would be tasked with flying delegates and politicians to Ottawa. Nicknamed the Roundels of Rebellion or Snooks Signatures, the roundels covered the center of the old RNAF Pinks. This act coupled with the suspicious fire on Black Friday that consumed all the records, photographs and precious artifacts of the RNAF, resulted in Snook's court martial and sacking. No proof could be found that he was connected with the fire, and technically, the Lieutenant Governor of Newfoundland, Sir Albert Walsh had not specifically stated which roundels to paint over the Pinks. So, Snook was relieved of command but not convicted.

The mysterious fire that consumed the memory of the Royal Newfoundland Air Force is why today there remains very little photographic and written record of the people, actions and history of this fighting force. Today what little is left comes from the personal archives, the limited photographs and the memories of its last officers and men - now in their 80s and 90s. Walter Snook died in 1982 at his Dildo home after a successful career as a commercial pilot. In 1950, after purchasing a surplus Vought Kingfisher from the Province of Newfoundland, he started Snook's Flying Services - Newfoundland's Finest. He spent the rest of his life flying in and out of the small ports and villages of coastal Newfoundland and Labrador making a living flying seal pelts to market, new nets out to fishing trawlers, towing banners (Lobster Supper - Church Hall - $3.25 - AYCE) and even doing the odd rescue at sea. In 1961, Snook started a scheduled service from Gander to the Faeroes and was partners in a Faeroes Pony breeding business. The airline soon ran into hard times and the breeding business faltered when pit ponies were outlawed in Nova Scotia coal mines.