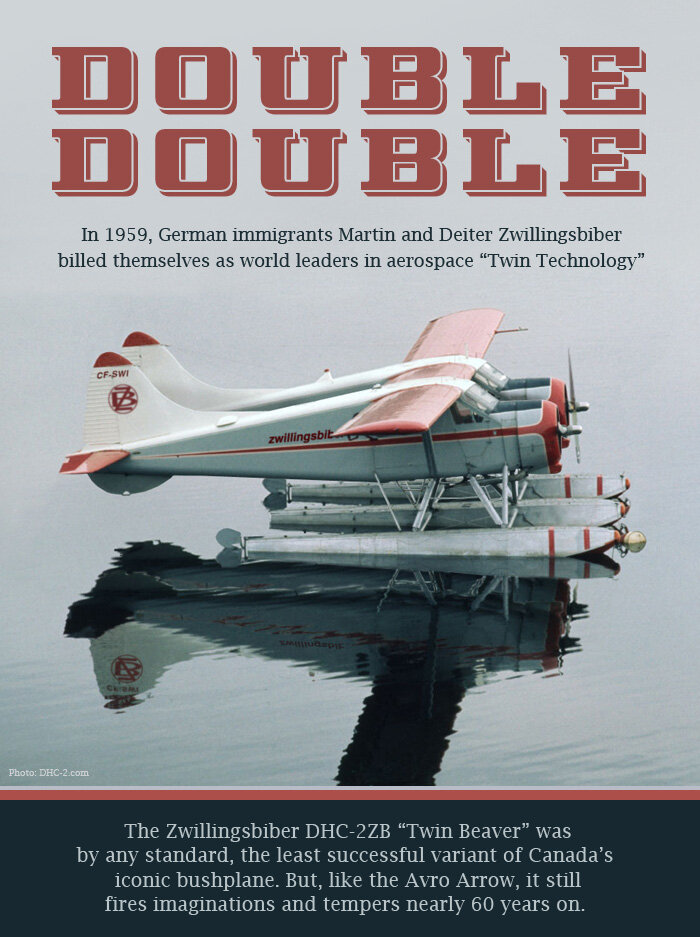

DOUBLE DOUBLE

First published April Fool’s Day, 2010

On Wednesday, August 11th, 1954, a tired looking and disheveled Dieter Zwillingsbiber, wearing the same overcoat as he did when he was captured in 1945, was shoved out of a drab green army van in the town of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern in East Germany. Waiting at the gate of the former Heinkel Flugzeugwerke factory were four former German POW Camp guards under guard by American MPs, all looking terrified and ashen in the early morning mist. This was the very spot, where nearly a decade before, Zwillingsbiber had surrendered to advance units of the Soviet Red Army, sent to capture technologies, intellectual properties and aerospace talent. Instead, they captured Zwillingsbiber.

The unfortunate Nazi camp guards were loaded into the van, which immediately roared off down the street in a cloud of diesel smoke barely discernible from the fog. They were never seen again. Zwillingsbiber shook hands with a German-speaking American colonel and then the MPs escorted him to a waiting Ford motor car. The whole event took only 4 minutes, but it was the end of a decade long ordeal for Zwillingsbiber and, as it turned out, for the Soviets.

Dieter Hermann Zwillingsbiber was born in Lauingen an der Donau, Bavaria, Germany in 1911, one of a pair of identical twin boys - Dieter and Martin. Their father was an agricultural tractor designer and entrepreneur with Klöckner-Humboldt-Deutz AG and was famous locally for his twin-tractor Deutz-Deutz combinations which helped increase Weimar Republic wheat production during the terrible years brought about by the Treaty of Versailles. The Zwillingsbiber brothers grew up around factories, machine shops and heavy equipment and were infused with an electrified German industrial energy far beyond their own abilities to utilize it. Though their whole lives were spent in and around machines with decidedly earthbound weight and function, they fancied themselves at the leading edge of technology and aspired to be aircraft designers like their heroes Kurt Tank, Willie Messerschmitt and the legendary Richard Vogt of Blohm and Voss.

At the age of 25 years, the two young men enrolled together (as they did their entire lives) in the newly created Grundschule für Flugzeugentwurf at the prestigious University of Erlangen-Nurnberg. Three and a half years later the two brothers emerged, battered and confused, but with diplomas in aerospace engineering. The war was just beginning, and trained aerospace engineers were in demand... no matter that the boys graduated last and second last in their class of 231 of Germany's finest technical minds. Though, it must be said, they were not exactly fought over by the great German aviation companies of the day, they did in fact begin their careers immediately with the Heinkel Flugzeugwerke in the north east corner of the country. Sadly, for the twins, their employment was not in the cigarette smoke-filled drafting rooms and noisy machine shops of the aerospace wing, but at the smaller Hilfskraftforschungsfabrik division across town which specialized in auxiliary power unit design, aircraft tractors and towing vehicles. Heinkel knew talent when they saw it.

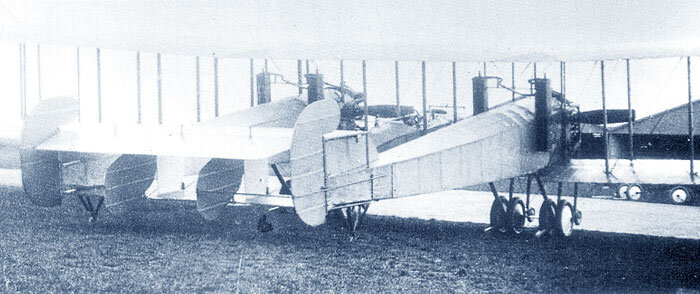

As the war progressed however, many of the best aircraft engineers and designers had either enlisted in the Luftwaffe or, as in the case of the entire design office at the Arado plant in Warnemünde, been killed in Allied bombing attacks. The Zwillingsbiber twins began a steady climb from the tug shop to the aircraft design and drafting hall simply by default. By 1941, the Zwillingsbiber twins were tasked with designing an aircraft capable of long range bombing and of towing the huge and ungainly Me 321 Gigant troop and vehicle carrying glider. Their answer to the problem handed to them was not to design a new aircraft, but to cobble together two existing Heinkel 111 medium bombers into one bizarre, ungainly and decidedly poor performing “twin” known as the Heinkel 111 Z-1 “Zwilling”.

Despite having five engines and a massive amount of wing area, the Zwilling, or as its pilots called it, the "Schiessevogel” (literally Shitbird), could not even complete its task of towing a loaded Gigant glider into the air. The Zwillingbibers admitted later that when calculating the power needed, they had neglected to compensate for the load that the glider would have to carry. In the end, the aircraft had to make use of RATO (Rocket Assisted Take-Off) in order to accomplish its primary task and even then the massive ship and its even larger tow, filled with 130 troops inside floundered through the air like whales on valium. The Zwilling was made in limited numbers, which in itself was evidence of growing panic and desperation in the Luftwaffe and in German aircraft production. The truth be told, the Zwilling made a much better long-range bomber and reconnaissance aircraft, but suffered from one very important drawback... it was easy to shoot down. Production was ponderous, only a few were built and none performed anywhere near the level of the single Heinkel 111.

The Heinkel 111 Z-1 Zwilling was one of the strangest aircraft to come out of the Second World War. Conceived by Dieter and Martin Zwillingsbiber, the five engined behemoth saw limited service as a glider tug. Photo: Luftwaffe, Bieber Family Archive

This rare topside photo of the Shitbird. The aircraft was designed to fly even if the three central engines quit. Like Zwillingers later Beaver design, capabilities were simply on paper and had no relation to the aircraft.

A very rare shot taken by a French civilian as a Zwilling flies over French countryside during the Second World War.

Related Stories

Click on image

A photograph showing Martin Zwillingsbiber standing behind the pilot of a Heinkel 111 Z-1 during test flights in 1941. As the photo seems to show, the introspective and kind Martin would always remain in the shadows behind the bluster of his brother Dieter, seemingly under some Svengali-like control. Photo Bundesarchiv

Another photo taken on a 1941 test flight - this one showing a serious Dieter in the left fuselage monitoring performance of the three central Jumo engines of the massive Heinkel 111 Z-1. Photo Bundesarchiv

Despite what should have been a dead-end street, the twin-obsessed Zwillingsbiber brothers worked until the very end of the war on improving the design. Unfortunately, the managers at Heinkel were no longer interested in the giant white elephant. With disaster around the corner, they sent Martin to work underground at the secret Heinkel He 162 Volksjager plant at Hinterbrühl. there he was kept out of trouble as a Quality Control manager 50 feet below ground. Dieter remained at Mecklenburg-Vorpommern as an office clerk until his capture by the Red Army in 1945.

When he was captured, Deiter Zwillingsbiber claimed to be Heinkel's senior designer, which, given that all the others had long ago headed for the American front line, he was. The Russians were under the mistaken impression that they had captured a weapons designer of the caliber of Verner von Braun, Kurt Tank or even Werner Heisenberg. They hustled him off to Moscow, and treated him with great respect, and though guarded always, provided him with a small apartment and even a car. Zwillingsbiber loved the special treatment. He was soon assigned to the Antonov Design Bureau in the Ukraine, where he was surrounded by the brightest and most highly regarded aircraft designers from the galaxy of Soviet satellite republics. Here, in front of them, stood a designer of the stature if Messerschmitt or Tank, whose genius had nearly broken apart the Communist Soviet and strewn it across the Steppe. The German aircraft designers were mythical, even to a young Soviet aircraft designer. Any one of these talented men would crawl over 100 kilometers of broken dreams to kiss the hand that had created the dihedrals and cambers at the leading edge of Nazi X-plane programs... perhaps even the designer of the Triebflugel, Bachem-Natter or Huckebein. Instead, Zwillingsbiber had designed the aircraft that had been then laughing stock of the Soviet Air Defence Forces - the mirth-inducing Shitbird, or as the Reds called it, the “Zavetnaya tsel'” (заветная цель) - the Dream Target.

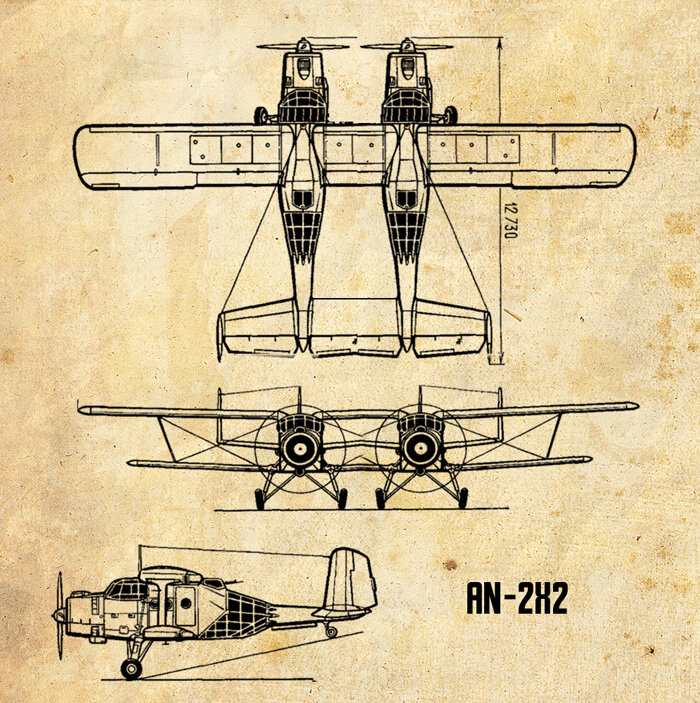

Due to his fixation on the bizarre side of aerospace design, it wasn't long before Dieter was taking the tram to work and sharing a filthy flat with four families. Left to his own devices at Antonov OKB, he proposed a number of strange aircraft concepts - a jet powered bi-plane, a supersonic bomber with fixed landing gear and a twin Antonov An2 for battlefield reconnaissance. After just one year, he was deemed harmless and left unguarded and unmonitored. After two years, he was back in the aircraft tug business, but when he designed a new three-ton tug that was to be integral to the actual aircraft fuselage itself and was to travel with the aircraft, Antonov had had enough. In August of 1949, Zwillingsbiber was transferred to a division of the bureau that had been retooled to meet a new quota for refrigerators, hotplates and laundry presses.

The immediately obsolete, oddly configured Antonov An2+2, never got farther than the drawing board. In a world of jet aircraft, it was a military aircraft of questionable value. Zwillingsbiber simply could not let go of the Twin Technology concept. Drawing: Antonov OKB Archive

By 1954, the Soviet authorities understood that Dieter Zwillingsbiber was neither a threat nor a benefit to Russian technology or society at large. He was asked if he wanted to return to West Germany and arrangements were made to exchange him for four notorious SS POW camp guards. Released in the early 1990s, the famous Mitrokhin Papers show that if Zwillingsbiber had refused to be exchanged, he would have been executed. On August 11th, he was a free man again. On August 12th, he began the search for his brother from whom he had not heard in more than nine years

Meanwhile, the fate of Martin Kaspar Zwillingsbiber followed a different route. He was captured by lead units of the Royal Canadian Regiment at Reichwald, Germany in early April of 1945. Unlike his brother Dieter, he kept his mouth shut about his Nazi Party affiliations and his self-proclaimed technological brilliance. His positive experiences with the Canadians piqued his interest in that country, and by November of 1949, he had emigrated to Canada. His first job was as a assembly line worker at the Massey Harris Ferguson tractor factory in Brantford, Ontario. Two years later, Martin was working as a mechanic and dispatcher for legendary Courtland “Stinky” Fowler's Fowl-Aire Airways in remote Sioux Lookout, Ontario. He had had no word from his brother in over 10 years and had assumed that he had died in the final battles on the Eastern Front or in a gulag in Siberia. In 1955, Martin received a telephone call from Dieter who had followed his trail to Brantford and within a month the two were reunited. Martin was not overjoyed.

Not nearly as ambitious nor as delusional as his brother Dieter, Martin enjoyed nearly a decade of peace after the war as a mechanic for “Stinky” Fowler's famous Fowl-Aire Airways in Ontario's north. Here he is seen doing an engine change in the bush in the winter of 1951. Martin would have preferred to remain anonymous for the rest of his life, but Dieter would make sure that the Zwillingsbiber name would become synonymous with failure for Canadian aviators. Photo: Sioux Lookout Heritage Museum

Unfortunately jobs in the world of advanced aerospace technology were scarce in Sioux Lookout. Martin kept his job with Fowl-Aire, while Dieter searched for work. He was in no hurry, as he had brought to Canada with him a considerable inheritance which had been left to him and his brother and which had collected interest for the past ten years. By June of 1956, Dieter had learned to fly at the Sioux Lookout Fishing and Flying Club and had bought a clapped out Luscombe Model 4. With little more than a commercial license and a couple of hundred hours flight time, he went into the aviation business under the name of DuM Airways (Dieter und Martin). Despite the aircraft's limited capacities and abilities, business was brisk and the twins settled in to make a living and a life for themselves in the Canadian hinterland.

Dieter (left) and Martin pose with the DuM Airways Luscombe in the winter of 1957. Despite the limited capacity of the little airplane, the brothers eeked out a decent living. Photo: Sioux Lookout Heritage Museum

In May of 1958, however, an ill wind blew into Sioux Lookout - a massive storm spanning three provinces and spawning extreme winds. Powerlines went down, buildings were flattened, trees were uprooted and, at the airport, nine bush planes were destroyed when they were blown from their tie downs. Two of those destroyed were de Havilland DHC-2 Beavers, the most capable and desirable of all. Unfortunately they were write-offs. But it seemed the wind, in addition to destruction, had also carried with it an opportunity, an idea and an old obsession. Dieter, always the dreamer, made a deal with their American owner, who wanted to collect the insurance anyway. Both Martin and Dieter were not necessarily on the same wavelength. The Zwillingsbiber inheritance was declining rapidly and Martin, was quite happy to work as a mechanic/dispatcher at Fowl-Aire and wanted to use his half of the family fortune to build a house for his new wife, Justina. He was not the dreamer Dieter was and he felt his future possibly slipping away.

But blood runs thicker than liquid assets, and Martin, always somewhat bullied by his brother, allowed him to use part of the family money to secure the wrecks. It was not Dieter's plan to restore the two airframes to two usable and salable de Havilland Beavers as Martin had hoped, nor was it his plan to use the aircraft in some sort of airline business as they were with the Luscombe. Instead, like an SS marching song record stuck in a groove, Dieter would build only one de Havilland Beaver – one that would show the world that he was an aircraft designer worthy of the Tank-Messerschmitt-Vogt heritage. Dieter would reprise his greatest (in his mind) moment, the Heinkel 111 Z-1 Zwilling using the de Havilland Beaver as the airframe. He barely thought about the aerodynamic and structural problems at all before offering the American owner a price that made them his (and Martin's).

CF-FKD, one of the first two Zwillingsbiber airframes after the big storm of 1958. Photo: Sioux Lookout Heritage Museum

Later, after he became the owner of two broken and un-flyable Beavers, he would back fill his design criteria to explain why he chose to build such a bizarre aircraft. In a business plan submitted to de Havilland to get their tacit approval for development, he cited some promising capabilities and performance numbers. He first suggested that the Beaver, widely considered the most capable of all bush planes of the day, could only be surpassed by one thing – two Beavers! If a fishing party, with people and equipment exceeded the limits of the aircraft, a Twin Beaver could do the job with just one flight and just one pilot. If a survey team was heavily loaded and needed to fly to an extremely remote location over 300 miles away, the single Beaver still needed to make two trips. A Twin Beaver could load one fuselage with fuel and the other with equipment and make the supply of the camp in half the time. With a possible configuration allowing for 16 passengers, the Twin Beaver could, according to Dieter Zwillingsbiber, operate on scheduled air routes in the North.

When approaching de Havilland Canada, Dieter had, of course, left out the fact that he had already committed two Beaver wrecks to the project. Instead, he mentioned in his plan, that he was considering the same Twin Technology using the Noorduyn Norseman or that Fairchild was considering opening their now-shut down F-11 Husky assembly line in Montreal to build a Zwillingsbiber Twin Technology Husky known as the Sled-Dog. Of course, this was all bluster. De Havilland could not know that Noorduyn would be bankrupt within the year or that Fairchild had never heard of Zwillingsbiber Aero, who billed themselves as “World Leaders in Twin Technology”. Though de Havilland already had an aircraft, the Otter, which did what Zwillingsbiber claimed the Twin Beaver could do, it was reluctant to relinquish market share to any company in the same sector. They signed a contract which allowed the Zwillingsbibers to build, test and possibly sell Twin Beavers, but only from used airframes. Luckily, for the German entrepreneurs, they had two handy.

Before the end of 1958, the Zwillingsbibers had leased an old hangar at the Sioux Lookout Airport, dragged the wrecked Beavers inside and began their Frankensteinian cutting, chopping and grafting. By the end of May, 1959, the prototype Zwillingsbiber DHC-2+2 Twin Beaver (CF-ZWI) was rolled out on floats and towed to the small lake called Black's Lagoon which stood next to the main runway. There was much legal to-ing and fro-ing with the Department of Transport about what identity the new Beaver should have – was it the serial number of the right or the left fuselage that would establish its identity? Was it the right – c/n 142, or the left one – c/n 177? DOT opted for a serial number made from the combined numerical order of the two aircraft – the new combined serial being 142177. The Twin Beaver floated on Black's Lagoon for a couple of weeks while DOT, de Havilland Canada and Zwillingsbiber Aero ironed out the details.

A 1973 photo of the old Zwillingsbiber hangar at Sioux Lookout, Ontario showing it age. It was here that Martin “The Beaver Cleaver” Zwillingsbiber transformed 12 de Havilland Beavers into the six Twin Beavers. The hangar was demolished in 1977. Photo: Sioux Lookout Heritage Museum

Each cockpit was equipped with full controls including two throttles for control of both engines. Control cables came out of both fuselages and crisscrossed in a web of wires in the space between and toward the back of the parallel Beavers. The weird pairing sat on three pontoons, one of which could double as a massive gas tank. By mid June, it was time for her first flight. The lake was 3,500 feet long, but the Twin Beaver, with Dieter at the controls, failed to get airborne after eight attempts. It was hauled out of the lake and towed to Minnitaki Lake, immediately North West of the airport. After just three tries, Zwillingsbiber, who had only two digit float time, yanked the beast clear of the water and after about ten minutes, had the Twin Beaver purring along at 500 feet.

The prototype DHC-2ZB Twin Beaver (CF-ZWI), fresh out of the shop, sits on the grass outside the Zwillingsbiber Aero factory in May, 1959, looking not bad in fresh paint and company livery. Photo: Sioux Lookout Heritage Museum

There is no doubt that Dieter, despite his lack of test pilot experience, could immediately tell there were “issues” with the design. Take-off and climb performance aside, sitting in the left hand seat of the Beaver, he just had to look out the right side of his aircraft to note the biggest problem. Immediately to his right, where there should have been a clear view of the airfield, traffic or the ground below, there was another airplane… only four feet away! There was no way to see round it, unless he had a copilot to look out for him. In a left hand circuit at an airport, he was fairly safe, and luckily lakes don't demand circuits in a particular direction. Even looking out the right side rear windows, all he could see was the tail of the Beaver next to him.

It took Dieter Zwillingsbiber four tries to get his new Twin Beaver back on the water. Not being able to see out one side of the aircraft had shaken his confidence in his flying, but certainly not in his aircraft design skills or his salesmanship. From now on, he would use the help of a test pilot. Using his German connections, Dieter was on the phone that afternoon to the world famous Kissmann Institute of Aeronautical Science in Rostock-Marienehe, West Germany. The senior test pilot at the Kissmann Institute, Paulus Rozen, who was understudy to Heinkel's senior test pilot of the Second World War, Gerhard Nitschke, agreed to fly to Canada to conduct further testing.

Rozen arrived on July 7th of 1959. Having lived his life in the industrial river valleys of Germany, he was overwhelmed by the remoteness of Sioux Lookout. Addicted to St. Pauli Girl, Trommler cigarettes and schnitzel, Rozen was shocked when he could not find a decent bierpalast or a schuhplattler show for 650 miles. Having been one of the test pilots on the Heinkel 111 project, he was familiar with the Zwillingsbibers and the Twin Technology concept, so he showed no emotion when he first laid eyes on the Twin Beaver. Though he said little when Zwillingsbiber fished for compliments, he surely must have been concerned. He thought the Beaver design was an exceptional aircraft, after all, the Yanks had scores of them in Germany and Europe, but what he thought of the Twin Beaver would not reveal itself for several months.

Not having float endorsement, he agreed to fly the Twin only if Martin put it back on wheels. He soon learned that floats would offer the best margin of safety. On wheels, the Twin Beaver, which the locals were now calling the Creature from Black's Lagoon, was even more bizarre. The design kept the inboard wheels and struts on both fuselages to help support the tendency of each fuselage to roll inwards. The two struts came together at the same point and shared the centre wheel. The aircraft rolled with incredible stability on three main wheels and two free castoring tail wheels. Rozen, fearing that higher pressure centre tire would cause "high-siding” leaving an outside tire with no contact, suggested that the tire on the centre strut pairing should be deflated somewhat to allow all the weight to sit on the outer wheels. This gave an effective wheel to wheel track of more than 20 feet with a wheel base of 23 feet. The almost square spread of rubber on the ground made for one of the most stable aircraft he had ever taxied or landed. Dieter was hopeful when this was revealed in the debrief.

On the runway, Rozen was able to take off without much problem, because the aircraft tracked as if on rails. The Twin Beaver was extremely sluggish in the climb. Essentially, the Beaver was twice the weight, with only about 55% of the wing area of two single Beavers. When Rozen opened the throttles at altitude to get the aircraft to climb, the airframes seemed to go into a sort of Galloping Gertie harmonic resonance like the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. The frightened German, throttled back immediately.

The Twin Beaver displayed great on-ground performance and not much in the air. Rozen found it fear-inducing to fly about the sky and land the airplane with no clue what was happening on the right side of the aircraft. After a few flights, and though he had mastered landing the strange aircraft, he conceded that the Twin had to have two pilots. In fact in the few examples that were built over the next couple years, a second pilot was mandatory if just to monitor passengers and keep them from touching the controls. The left fuselage pilot or captain could not simply speak directly to the second pilot, but had to speak to him only by intercom. Since both fuselages had both seats still installed with dual controls, the Twin Beaver had in fact accommodation for four pilots. Dieter saw the four-pilot configuration as a selling feature and later, to American military clients, touted the Twin Beaver's training capacity of one instructor and three students.

During the last few weeks of test flying, Rozen was joined by the low-time Dieter Zwillingsbiber in the right seat of the starboard fuselage, to watch for air traffic and mountains. Martin's first rate mechanical skills were constantly pressed to keep it flying and to tweak systems. On the second-to-last test flight conducted by Rozen, Dieter attempted to join the master in the port fuselage by opening the port door of the starboard fuselage and doing a little “strut-walking”. This is when he discovered the Bernoulli effect generated by the proximity of the two fuselages. The airflow and the prop wash combined and compressed into the space between the fuselages sped up considerably. The reduced pressure resulting from the faster air ripped the door from his hand. It snapped open, and Zwillingsbiber fell outward slightly, but because it was hinged at the front, the door was immediately slammed back by the slipstream and hit him in the face. In the instant that the door was open, all his notes were sucked outside and scattered over Northern Ontario.

During the last few days of the “test program”, Dieter had made contact with the United States Army and Air Force. Of the nearly 1,700 Beavers built by de Havilland Canada, an incredible 980 were sold to the United States military. Here, Dieter was sure, was the big market for the Zwillingsbiber operation. He envisioned endless pairs of USAF and Army Beavers being flown from America, north to tiny Sioux Lookout where they would be mashed into a much more capable Twin Beaver. It is important to note here that, despite the poor performance to date, Dieter was certain the bugs could be worked out and that he could deliver as promised.

Unbelievable (unless you were Dieter Zwillingsbiber) he managed to convince both the US Army and the USAF to send a pair each of early delivery Beavers to Sioux Lookout for conversion. The USAF, which was experiencing a shortage of pilots for small aircraft, was considering the possibility of a larger air ambulance that could take up to eight litters from a forward area airfield – doubling the capacity with the same crew. The Army wanted to keep up with the Air Force, so bought into the program.

By March of 1960, the old Sioux Lookout hangar had become a bustling conversion assembly line, with the four American Beavers more the halfway through the conversion process. A somewhat reluctant Paulus Rozen returned in late May to ferry, with Dieter, the first Twin Beaver production prototype all the way from Sioux Lookout to the US Army Aviation Center at Fort Rucker, Alabama for evaluation. It was a grueling three day flight and if Rozen thought he could get a cold St. Pauli Girl Lager in dry Dale County, Alabama, he was sadly mistaken. The two Germans spent three full weeks training Army test pilots on the performance of the strange concoction. All the while Dieter promised them that the fixes for performance problems would be published shortly.

The US Army test flew the Zwillingsbiber U-6AX2 Twin Beaver in 1960. Despite promises, it never lived up to expectations. Photo: US Army Aviation Centre Museum

On returning to Sioux Lookout, they immediately picked up the just-finished USAF conversion, and brought it to Edwards Air Force Base test establishment in California. Taxiing the weird Twin Beaver along a line of modern jet fighters, including an F-104 Starfighter, a B-58 Hustler and finally an X-15, poor old Paulus Rozen was mortified and shrunk down in his seat. Dieter was oblivious. There can be no doubt that the de Havilland DHC-2 was and is one of the most important developments in the light cargo, bush aviation field – a simple and grand aeronautical engineering triumph. But the Twin Beaver was, for Paulus Rozen, a former test pilot who once flew the Heinkel 280 jet fighter in 1943, an embarrassment of Frankensteinian proportions. During the ensuing training period, the Base Commander who flew along with Rozen in the starboard fuselage while two other USAF pilots rode the in port side, told him “This rig reminds me of that big Kraut abortion where they welded two Heinkel's together back in the war. Remember that? I shot one down in my P-47. I put a two second burst into the middle of that piece of crap and it folded up like a garage door. Poor saps inside!” With that, Rozen had had enough. He flew home to Germany the next day.

The United States Air Force studied the limited capabilities of the U-6AX2 at Edwards Air Force Base in latter part of 1960. Photo: United States Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio

While the US Army and the USAF worked their way towards the inevitable conclusion that the Twin Beaver was not what they had been promised, Dieter had used the advances from the Americans to purchase six more used Beaver airframes and was now touring the northern parts of Ontario and Quebec expounding the unique attributes and unfulfillable promises of the Twin Beaver. With CF-SWI now back on floats and his experience growing with every flight, he dropped into mining communities, fishing lodges, mineral exploration camps and visited bush-operators where ever he could find them. It was a hard slog. Wary backwoods operators were not convinced and many had already placed orders for the new and highly touted de Havilland Otter. When no sales were made, the still-enthusiastic Dieter Zwillingsbiber turned to his best bet – the military. With big budgets to spend, none of which was their own money, equipment procurers for the Royal Air Force in Ottawa, fell for the sales pitch, the steak dinners, martinis and strippers of Hull, Quebec. They would purchase one of the three remaining double airframes in Sioux Lookout. But first, they devised a test for the Zwillingsbibers.

If Dieter's design skills might be considered suspect, his marketing skills were sharp. I found this match book and a set of naughty playing cards in an antique store in Kirkland Lake. Dieter understood the power of sex when it came to selling to miners, lumbermen, soldiers and men in remote places. If the owners did not line up to buy his airplane, their employees most definitely gathered round to get some of his swag, like this “Flying Saucy” match book. Photo: Evad Yellamo

One can only smile when we look at what, in 1959 and 60, would have been considered porn. Dieter Zwillingsbiber would hand out his set of sexy “Let's Play!” playing cards to mechanics, pilots, lumbermen and miners alike and one can only imagine the games played round the campfire, tent or cabin. Great swag however does not make great products or sales and Dieter went away empty handed, while the guys most certainly did not. Photo: Evad Yellamo

On a sales and promotion tour of the north, Dieter Zwillingsbiber arrives at a remote Canadian mining camp on Stripmine Lake near Chibougamau, Quebec in 1961.

The Zwillingsbiber “production line” showing the tails of at least two of the final three Twin Beavers being joined together. Photo: DHC-2.com

The Royal Air Force was, at that time, conducting weather research out on the ice pack of the Foxe Basin. With a floating ice camp resupplied by ship, it was problematic getting materiel and personnel to the site, which was constantly moving south. From time to time, the camp would have to relocate farther north and the efforts of moving it over the surface of the ice, or breaking through with a ship caused many headaches. The RAF hoped that the long range, cargo capacity of the Twin Beaver, combined with the legendary ruggedness of the single Beaver, might just be the answer to their prayers. The test involved Zwillingsbiber, accompanied by an RAF pilot with Second Word War Coastal Command experience, to navigate the Beaver 750 miles from James Bay to open water at the edge of the ice shelf, just south of Prince Charles Island. The two would rendezvous with the Canadian Coast Guard ice breaker CCGS Tabernack. If he could do it in just one hop and land safely on the open water beside the supply ship, the RAF would seriously consider a purchase of six Twin Beavers.

In late August of 1962, Dieter and Squadron Leader B. F. Twatt, DFC and Bar, took off from the open water in the western channel of the Moose River, next to the Moosonee airport. Dieter flew from the left seat of the left fuselage while Twatt sat in the right seat of the right. The aircraft had just been painted in a bright red RAF color overall and had roundels on its fuselages and wings. Dieter claimed this would allow for easy spotting on the ice, but of course it was for marketing purposes first. Dieter told Martin before he left that the British would never change their minds about purchasing at least this one if it already wore their colors.

The flight was uneventful and seven hours after take-off, Dieter was making left hand turns around the ice breaker Tabernack, which was tied firmly to the edge of the ice shelf south of the island. The Canadians on board lined the railings to watch Dieter circling to find an open area free of floating growlers and bergy bits. On landing, the delighted Zwillingsbiber-Twat team brought the Twin Beaver right up to the stern of the former ice-breaking St Lawrence River steamer. As the three pontoons nudged the edge of the ice, Twatt, standing on the right pontoon, tossed a rope to the sailors waiting. Mission accomplished – sort of.

A somewhat forlorn Dieter Zwillingsbiber stands on the ice next to his all red RAF Twin Beaver and CCGS Tabernack having navigated with Twatt over 750 miles from southern James Bay to Prince Charles Island. Though proud of his accomplishment, he did not get the response from the RAF he had hoped for. Photo S/L B. F. Twatt, RAF

Over the last three hours of the flight, Dieter had found that the Twin Beaver was vibrating more and more. He noted a “wobbling” effect when he looked over at Twatt sitting in the adjacent fuselage. Twatt reported the same thing – a sort of “jello-ing” visual effect like one would have when one holds a pencil lightly between thumb and index finger and waves it up and down. Twatt was increasingly more distressed as the flight extended farther and farther from land, but he concentrated on getting the aircraft to its rendezvous point and to safety. Once he had the Twin Beaver tied up, Twatt grabbed his flight bag and his luggage and stepping off the pontoon, turned to Zwillingsbiber and said, “They can court marshal me “Beebs” (his nickname for Dieter), but I won't spend ten seconds more in that bloody Rube Goldberg machine of yours… I am sure I saw the bloody wings bloody flapping!! Bloody hell.”

Dieter's moment of triumph came and went in seconds, shot down like a Shitbird. After an embarrassing dinner aboard the Tabernack, Dieter slept poorly. Twat refused to go with him on the return trip the next morning and he was without a navigator. But, Dieter was certainly not going to simply leave the Twin Beaver sitting moored to the ice while he left on the ship for Frobisher Bay.

Despite being tired and stressed, Zwiilngsbiber awoke the next morning ready to go it alone. He had the Twin Beaver refueled from a tank on the ship while he studied maps with the ship's navigator. His plan was not to head back to Moosonee, but rather to follow the west coast of Baffin Island all the way southeast over Foxe Peninsula and to land at Frobisher Bay (today's Iqaluit, Nunavut).

With wind blowing the Twin Beaver hard against the ice, he requested a ship's boat to tow him out to take off. Shortly after 9 AM, the morning of August 27th, Dieter pulled the throttles out of their detentes and shoved them upward. The Beaver lumbered along picking up speed, but in his haste, Dieter had chosen to take off in the direction of the ship and the ice flow to remain close to rescue in the event of an accident. Unfortunately, this meant he was taking off in the same direction as the wind. His airspeed crept up, but not high enough to get airborne. The Twin Beaver started vibrating ominously. He could barely read the instruments. Between the fuselages, he heard a loud crack and looking to his right, saw the cross struts flapping and banging against the fuselage, now no longer connected at the top. He became frozen in his seat, pulling hard on the yoke, but not even trying to chop the throttles. Though there were no obstacles in his way, he never did get the floats unstuck from the water and they sheared off as he struck the ice. Without the structural strength afforded by the float undercarriage, the red Twin Beaver, collapsed like a deck chair, folded in two and slid for more than two hundred yards on the ice, the two fuselages coming to rest side by side but definitely not connected.

Dieter was unhurt, but his pride, the family wealth, the future of Zwillingsbiber Aero and his dream lay scattered over the Arctic ice like broken toys. Rescuers arrived within minutes, but nothing could be done to console the pilot/designer. When they arrived, they found Dieter standing between the fuselages staring at the snapped centre section wing and muttering something about poor Canadian design. Dieter would never fly again.

The RAF Twin Beaver sits in shambles on the ice south of Prince Charles Island in a poor image from that day. The RAF had brought a small dozer from their weather station and offered to tow the wreck to shore where Zwillingsbiber could salvage it. Instead, a despondent Dieter ask them to push it to the the edge of the ice and dump it into Foxe Basin. RAF Photo

Back home in Moosonee, Martin, who now was called The Beaver Cleaver by townsfolk, was just finishing up the remaining two Twin Beavers when he got a short wave radio call from Dieter in Halifax where he was dropped off. The RAF had cancelled the program. Two weeks later the USAF and the US Army put their Twin Beavers up for sale. Dieter never came back to Sioux Lookout, leaving Martin to wind down the company. By February of 1967 the last two aircraft were sold off and the doors of Zwillingsbiber Aero were shut permanently. To get away from creditors who were hounding him and his wife Justina, Martin changed the family name to Biber and then to Bieber and moved to London, Ontario. His grandson Justin, named after his wife would become a world-famous singing sensation. Martin lived in Guelph, Ontario until until his death at 98 in 2009.

Dieter's dream of joining the pantheon of the great aircraft designers had never been achievable and the crash of the RAF Twin Beaver finally convinced him so. He moved back to Germany in 1964 and was murdered by strangulation in 1968 by Paulus Rosen. In 1967, De Havilland Canada ceased building the DHC-2 Beaver, citing, among other things, decreased demand for their aircraft following the bad press surrounding the Foxe Basin Incident and the demise of Zwillingsbiber Aero. The Beaver remains today the finest aircraft ever designed and built in Canada.

The Last of the Twins – Where are they today?

Though the Zwillingsbiber Aero enterprise was, by all measures, a failure and though the original Twin beavers lacked performance equal to even the single Beaver, it is a tribute the solid German work that went into them that five of the six Twin Beavers built still fly today, a half century after they were conceived. In fact, the Zwillingsbiber Twin is somewhat of a cult aircraft and the price for one makes them the playthings of only the wealthy. There had been a rumour a few years back that demand was so great, that Sydney BC's Viking Air Limited was considering building a short run of them. Given that presently, Viking has restarted a de Havilland DHC-6 Twin Otter assembly line with dozens of orders, it's not much of a stretch to imagine Zwillingsbiber Twin Beavers coming off their line.

Thanks to Neil Aird, the world's leading authority on the DHC-2 Beaver and its history, I was able to track down images of all five of the remaining Twin Beavers and even some contemporary photographs.

By 1967, Martin had managed to sell off all three of the remaining Twin Beavers. Of the six, the US military was still disposing of theirs and the RAF airframes were at the bottom of Foxe Basin. The last to go was the original prototype which Dieter had flown for a total of 622 hours. Before the last three could be sold, the “interwing” (the small section of wing between the fuselages) was strengthened to eliminate the vibration. Oddly enough, this improved its flying characteristics and made it a much more pleasant aircraft to fly. It still required two pilots or at least an occupant with good vision in the right fuselage. After the upgrade mods, CF-ZWI received a newer gray paint. It was the last to go. Here it is seen moored at Lac Beegfishinapan, Quebec in 1969, still with its Zwillingsbiber markings. Photo: DHC-2.com

CF-ZWI still flies today registered as N930AJ, with a colourful paint scheme and, strangely enough, for a Swiss company called Beav-Air, promoting, of all things, de Havilland watches. Here we see her taking off from Lake Geneva. Photo: Neil Aird, DHC-2.com

A photo of the former prototype Twin Beaver CF-ZWI, now N930AJ . There is no doubt that the Twin Beaver from certain angles is an impressive sight. From below, the triple floats, double fuselages and broad wing span look powerful from and, dare I say, elegant. Photo Neil Aird DHC-2.com.

The cockpit of a Zwillingsbiber Twin Beaver is much the same as any single Beaver, save for the dual throttle, propeller pitch and mixture controls in the centre of the control panel. This is the cockpit of N930AJ, the former CF-ZWI prototype hand built by Martin Zwillingsbiber. Photo by Neil Aird, DHC-2.com

After its time at Edwards AFB, the former USAF Twin Beaver was stored at Davis Monthan Air Force Base for a number of years and was eventually sold to a private owner in 1970 and registered as N23SWB. Today, N23SWB operates out of Van Nuys, California, and is owned by Hugh Hefner, who has a thing for twins. Photo: DHC-2.com

The final two Twin Beavers to come out the door at Sioux Lookout were painted in the new “Factory Scheme” designed by Martin. He was keeping it as a surprise for Dieter upon his return from the Foxe Basin demonstration. Dieter would never see them. Martin had registered them as CF-MKZ (for Martin Kaspar Zwillingbiber) and CF-DHZ for his brother. Martin was always trying to please his twin, but in the end was relieved by the final outcome and not sorry that Dieter never came home. Here we see CF-DHZ flying on a delivery flight to its new home in Saskatoon in the late 1960s. CF-DHZ was abandoned in the Northwest territories in the 1980s. It was rescued and rebuilt in 1997. CF-MKZ went through a number of owners, finally finding a home in New Zealand where she flies toady as ZK-BVR. Photo Bieber Family

One of the two last Twin Beavers built, CF-DHZ languished for nearly a decade at S'tukinnamuk, Northwest Territories. Today she has a new lease on life as C-FOCV and operates out of Lac Ladouche for Armstrong Outposts and Air. Photo via Armstrong Outposts.

Privately owned Zwillingsbiber Twin Beaver CF-MKZ lands at Vancouver in 1989. When, millionaire owner Buck Castor wanted first hand information on the care and feeding of the Twin Beaver, he tracked down Martin in Guelph (as Martin Bieber) and invited him to the West Coast. Martin was honoured by the consideration and he and Justina spent six days with Castor sharing inside information and insights. It was the only time Martin would ever work on the Twin Beaver after the demise of the company. Photo: DHC-2.com

The memory of Martin Kaspar Zwillingsbiber and his obsessed brother lives on in New Zealand with the former CF-MKZ now for sale in New Zealand. Registered as ZK-BVR in New Zealand, the Twin Beaver (c/n 567793) looks to be in beautiful shape. Photo: DHC-2.com

One very successful commercial operator of the de Havilland Beaver is Kenmore Air of Washington State. In business since 1946 and highly regarded for their expertise worldwide, Kenmore was the only company to operate the Twin Beaver with success and safety. The company, which has extensive overhaul and restoration facilities, made many modifications to the aircraft to make it safe and in fact make it profitable. They operate the aircraft on regular scheduled service up and down the North West Coast and are the world's only qualified instructors on the rare aircraft. They are the only company certified by the FAA to fly the Twin Beaver with only one pilot. Well known West Coast aviation photographer Franz Loew captured Twin Beaver N6781L, the former US Army single test airframe, in this stunning air to air shot of four (some say five) Kenmore Beavers in the air over Puget Sound. In all my searching on the web, this Airliners.net image is the only shot I could find of a Twin Beaver in the company of other Beavers. Taken from a helicopter, this is one of the finest shots of Beavers you might ever see. Photo By Franz Loew at airliners.net

There has long been a fascination with the Twin Beaver, though little is known about its roots and technological history. There is no known model kit of it, but Hans Jürg built a flying model of the famous aircraft mashing together two Beaver kits into one – much the same way that Martin and Dieter did so long ago. Check out the shots of the Twin Beaver in flight, soon to be featured in the Swiss RC Modeler magazine Modell Flugsport !

Photos via Hans Jürg

Twin Technology - Dieter was not alone.

Though Dieter Zwillingsbiber had a fixation with Twin Technology projects, there was nothing much in the world of aviation history which would seem to support the idea that slamming two already designed and proven success-story fuselages together would, in fact, create a better aircraft. Perhaps it was just laziness. Why design an entire aircraft from scratch only to find out it was a turd in the air? Why not just figure out how to connect two already legendary aircraft?

History is, as it turns out, full of examples of aircraft made from other aircraft as well as purpose-built concoctions conceived right from the start as twin fuselage aircraft. Many, like Dieter's Twin Antonov An-2X2, were simply concepts that reached only the drawing board or model shop. Germany, in the closing years or the Third Reich, had many examples of conceptual twin fuselage aircraft, such was their desperation. After looking at many twin-fuselage designs, only a few can really be said to be successful. The F-82 Twin Mustang is perhaps the best example with the highest production. But, as we stand today at the very edge of private space travel, Dieter's concepts for the Heinkel and the Twin Beaver, may not have been that quirky or dumb after all.

Part of the reason that the United States Air Force even considered the Twin Beaver, let alone tested it, is the remarkable success they had with the North American F-82 Twin Mustang, arguably the only truly successful attempt to bolt together two identical air frames. The F-82 was the last American piston-engine fighter ordered into production by the United States Air Force. Based on the P-51 Mustang, the F-82 was originally designed as a long-range escort fighter in the Second World War; however, the war ended well before the first production units were operational, so its postwar role changed to that of night-fighting. The Twin Mustang, however, was dropped from service in 1953, more than seven years before the USAF took a look at the Twin Beaver. USAF Photo USGOV-PD

One imagines that Dieter Zwillingsbiber envisioned a production output like that of the Twin Mustang with a breataking 270 being built at the North Amwrican plant at Inglewood, California. USGOV-PD

The Thomas-Morse MB-4 was a prototype American mailplane of the 1920s. It was of unusual design, being a biplane with twin fuselages housing the crew of two and a central nacelle which carried the aircraft's twin engines in a push-pull configuration. he MB-4 was a failure, having extremely poor flying characteristics and being described as the "worst thing on wings", and saw no service other than the trials by the manufacturer, US Army and the US Post Office. Only 2 were built.

The Wight Twins. The Wight twin-fuselage landplane was ordered by the French government in August 1914 but crashed on test at Eastchurch. It was a twin-engine, two-seat, five-bay (structure) biplane, twin-float torpedo-carrying seaplane with twin fuselages.

Aeroflot Savoia-Marchetti S.55P The S.55 featured many innovative design features. All the passengers or cargo were placed in the twin hulls, but the pilot and crew captained the plane from a cockpit in the thicker section of the wing between the two hulls. The S.55 had two inline counter-rotating propellers, achieved by mounting the twin engines back to back. The engines were canted sharply at an upward angle. Two wire-braced booms connected the triple-finned tail structure to the twin hulls and wing.

Known as the T.B. or Twin Blackburn, this machine was a large biplane of unusual design having two wire-braced, fabric-covered, box girder fuselages, each with its own rotary engine, joined by a 10 ft centre section forward and a common tailplane at the rear. The fuselages were supported on the water by separate and unconnected bungee-sprung, stepped pontoons, and small tail floats were attached at the rear by short steel struts. Nine were built.

The Fouga CM.88 Gemeaux was a 1950s French engine test-bed aircraft produced by Fouga. An unusual aircraft as it was two aircraft joined by a common wing. To meet a requirement to use as an engined testbed for Turbomeca turbojets, Fouga combined two CM.8 fuselages. It used the port and starboard outerwings with a new wing centre section to join the two fuselages. The V-tails fitted to each fuselage were joined at the top in a W configuration. The type was designated the Fouga CM.88-R Gemeuax I and first flew 6 March 1951, it was fitted with two Turbomeca Piméné turbojet, one on top of each fuselage. Further variants were produced as the engine fit was changed.

The Twin Cub was the brainchild of Mr. Harold Wagner of the Wagner Aircraft Co. at Troh's Skyport, Portland, Oregon. He wanted to create a simple and cheap twin engine SUV type aircraft and started experimenting with a PA18 Super Cub which he equipped with a second engine on top of the fuselage. The sports utility aircraft made its first flight on May 29, 1952 but tail flutter caused by the down thrust of the extra power plant meant that the Twin Super Cub project had to be ended prematurely after only 8 hrs of flight time, after which the Super Cub was returned to stock configuration.

Mr. Wagner's second attempt produced an even uglier machine, called the Twin Cub. It consisted of a J-3 Cub and a PA-11 Cub Coupe fuselage mounted side-by-side using a small wing center section and central tail plane. The outer wing panels and tail plane were standard components. The resulting aircraft looked so odd that even Mr.Wagner called it "The Thing". Because of the close proximity of the fuselages, only the right hand one could be occupied by a pilot and passenger, the left hand fuselage serving only the purpose of engine mounting.

Even though the purchase price was said to be about half of a regular twin engine aircraft, the Twin Cub remained a one-off and Mr. Wagner turned his attention to the Twin Tri-Pacer, where he bolted two engines to the nose of an otherwise standard Piper PA-22 Tri-Pacer. None of the Wagner conversions achieved commercial success.

Postscript

Dear old Dieter and his reluctant brother Martin may have been on to something all along. It seems the world's most innovative, celebrated and respected aircraft designer today, Burt Rutan, took a page from Dieter's book for the design of his spaceship launch vehicle White Knight Two. Perhaps after all, the Zwillinsbibers deserve to be in that pantheon - Messerschmitt–Tank–Rutan–Zwillingsbiber–Vogt. Why not?