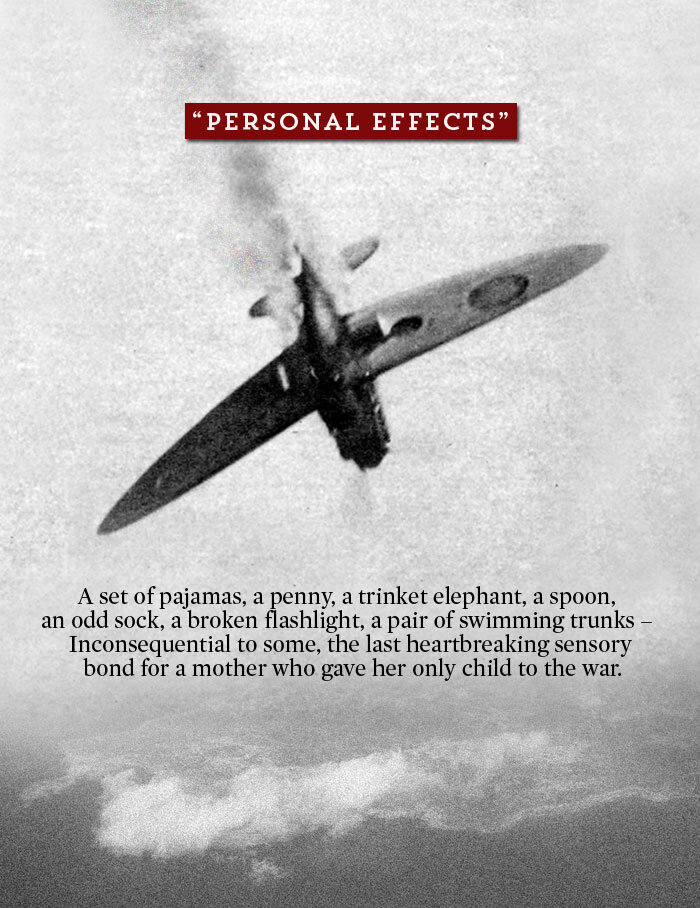

PERSONAL EFFECTS

3 June 1942 — Over the Mediterranean, west of Malta

At around 11 o’clock on the sunny morning of 3 June 1942, a dogfight erupted a few thousand feet over the Mediterranean Sea just to the west of Malta, near the island of Gozo. Nine pilots of unarmed Supermarine Spitfire Vs were attempting to run the gauntlet and deliver themselves and their vital aircraft to airfields on that besieged island. Earlier that morning, they had all taken off from the aging Royal Navy aircraft carrier HMS Eagle. Now, after the long ferry flight, and with the island in sight, it looked as if they were going to make it. That’s when they were attacked by twelve Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter aircraft from 11 Gruppen of Jagdeschwader 53.

The exact events of the fight are not known, but the Spitfire pilots could do nothing other than manoeuvre defensively and find a way to press towards Malta and safety. The fight was horribly one-sided and when the skies were silent once again, three young Allied airmen had crashed into the sea and died and another was floating in his dinghy waiting for rescue. He too would never be seen again. The young men were Flight Sergeant Thomas Francis Beaumont of Great Britain, Flying Officer James Menary of Ireland, Flight Sergeant Hugh MacPherson of Vancouver, Canada and Pilot Officer David Francis Gaston Rouleau of Ottawa, Canada. The Mediterranean Sea, instantly and without malice, folded them into her cold embrace and sealed shut the stories of their lives. In the multi-continental cataclysm that was the Second World War, these four men were just another barely audible click of the odometer of suffering. That journey towards peace would last three more years and the memories of these four men were lost like a child’s cry in a hurricane.

Two years previous

David Rouleau, one of those four lost airmen, was a gentle, wide-eyed, and soft-looking young man from Ottawa, with a taste for English literature and drama. He was the kind of youth that would likely have become a kind and inspiring teacher rather than a fighter pilot, but the war, with its dramatic and heroic subtext, made wrathful, winged avengers of even the meekest of men.

In the summer of 1940, his mother Gertrude was living with her father, Dr. Francis Hernaman Gisborne at 114 The Driveway, along the edge of the Rideau Canal. Her 84-year-old father was formerly Assistant Deputy Minister of the Department of Justice, Parliamentary Counsel to the House of Commons and a leading figure in the Anglican Diocese of Ottawa. She had moved back there with David, her only child, after the death of her husband, the accountant Honoré Gaston Rouleau in the spring of 1929. David had been just eleven at the time and she had remained protective of her boy ever since. When he had told her just two years before that he was joining the Royal Canadian Air Force, she felt her world slipping out of her control. She remembered it well. David had just returned from University of Toronto after graduating with a Bachelor of Arts. It was the height of the Battle of Britain. Young men like David had seen only the romantic notion of heroic fighter pilots saving the world from tyranny, but Gertrude had seen only sons like hers going down in flames to their deaths.

By the end of November of that year, David was flying Fleet Finches at No. 13 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) near the small hamlet of St. Eugène, Ontario close to the Québec border and things were going well. He was only an hour and a half away by train, and the train station was only a 15 minute walk from the family home. Gertrude and her father felt lucky to have him home for Christmas. Most of the young men at 13 EFTS ate their turkey dinner in the mess hall that year.

A smiling David Rouleau during happier times, learning to fly at No. 13 Elementary Flying Training School at St. Eugène, Ontario—judging by the excited look on his face, likely his first ever flight. When contemplating this image and the following two photographs, one cannot help but see the innocent boy in Rouleau, the sweet and only child of a mother about to sacrifice her heart to the war effort. Immediately upon graduating from the University of Toronto, he volunteered with the RCAF, arriving at No. 13 EFTS on 29 November 1940. Three months later on 28 February 1941, he graduated to Service Flying Training and was transferred back to Ottawa and No. 2 SFTS at Uplands. Looking closely at the Finch in the background, it appears as new to flying as Rouleau was—not a mark or stain on it anywhere. Photo via Peg Christie

Gertrude likely worried constantly, but his proximity would have made it easier to take than she had thought. Her boy left St. Eugène in February of 1941 and took the train home for a short visit before beginning his Service Flying Training in Ottawa at No. 2 SFTS Uplands. He was now only a half hour bus ride away. She could see him on his infrequent days off. Whenever a Harvard training aircraft roared up the Rideau Canal, she would wonder if it was him. Unlike most mothers of student pilots of the Royal Canadian Air Force, she could still expect him home for Easter dinner in 1941. Shortly after that, it was likely that Gertrude, Dr. Gisborne and family friends attended David’s Wings Parade, held indoors in a hangar at Uplands because of cold weather. It would have been a proud but unsettling event for Gertrude. Her son was among the elite—a dashing young aviator destined for England and flying the famed Supermarine Spitfire. As proud as that made her, the fact remained that this was a deadly pursuit. The future held no promise that he would return to her. The local papers brought daily news of other mothers’ losses and her heart was heavy.

In a few days, her father would drive her and David to Union Station and inside the vast echoing volume of the great waiting hall, they would say their goodbyes sitting on the dark oak benches. I can imagine how it went. As the announcer calls for passengers to board the Canadian National train to Montréal, Québec City and points east, David shoulders his kit bag and walks along the platform with his mother and grandfather. He was heading to Debert, Nova Scotia before boarding a troop ship for England. Steam rises from under the cars, porters call for a final boarding, light streams in from the soiled glass roof of the train sheds. At the far end of the platform, beyond where the shed ends, the locomotive huffs and steams in the sunlight, seemingly anxious to pull. It is time for a last kiss and a few tears. David is likely stoic, but Gertrude is ashen, worried for her son, Dr. Gisborne stands away to grant them their space. Their hearts are heavy. The world is in motion, and it cannot be stopped. David holds his mother at arm’s length, assuring her he will be fine. He looks so handsome and so young. He turns and steps from the platform to the train’s stair and climbs aboard. He enters the car and Gertrude sees him wave to her from inside. She lifts a gloved hand, waves back. She is crying. Her father takes her elbow and turns her toward the hall. They never see David again.

A rather boyish David Rouleau accepts an awkward handshake from Group Captain Frank Scholes McGill, the Station Commander of RCAF Uplands at his Wings Parade on 4 April 1941. Photo via Peg Christie

Related Stories

Click on image

Rouleau, shortly after the April 1941 ceremony in which he was awarded his pilot’s wings. He still wears the white cap flash of a student pilot, though by this time, he is entitled to remove it. Gertrude Rouleau was more fortunate than most mothers of airmen of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan in that David did both his Elementary and Service Flying Training within 60 miles of home. Uplands is just a short 30 minute bus ride from the family home along the Rideau Canal and No. 13 EFTS St. Eugène, where he learned the rudiments of flying, was just 60 miles to the east and on a rail line to Ottawa. That meant she likely had the benefit of having him home on many weekends and at Christmas. She was also able to attend his Wings Parade. Photo via Peg Christie

He had left for England and operational training in May of 1941, joining 53 Operational Training Unit (OTU), a Spitfire OTU at RAF Heston. Later that month he transferred to 61 OTU, which was just being stood up at Heston. Once qualified on the Supermarine Spitfire, David was assigned to 131 County of Kent Squadron, a recently re-formed squadron from the First World War and a Spitfire unit at RAF Ouston. For much of the next year, young David flew the Spitfire I, II and Vb, growing in confidence and experience, flying air defense for convoys and “rodeos” over France. Sometime in the spring of 1942, David either volunteered for or was selected for service with a squadron on the island of Malta. For a young man inspired by the stories of the Battle of Britain, the aerial battle taking place over Malta had the same hallmarks of a titanic struggle against overwhelming odds. If a pilot had missed the Battle of Britain, Malta offered young men the chance to bring the fight to the enemy every day, to become an ace and a legend and to test their mettle in one of the biggest and longest aerial battles of the war.

Spitfire Vs of 131 County of Kent Squadron prepare for battle. Photo: RAF

Operational record books for 131 Squadron show that Rouleau flew his last operation with the unit (a scramble against enemy aircraft) on 4 May 1942. He likely left the unit shortly after that date and went on leave before getting ready to sail for Gibraltar. It is also likely that he trained briefly to take off from an aircraft carrier, for after sailing for Gibraltar aboard Empire Conrad, he boarded the carrier HMS Eagle. Two days later, he and 31 other pilots launched their new Spitfires, in four waves, from the deck of Eagle. He was among the last flight of nine pilots to depart. Two hours later, Rouleau, Menary, Beaumont and MacPherson were dead.

Three Days Later — 6 June 1942 Ottawa, Canada

On the evening of Saturday, 6 June 1942, the weather was much like any summer evening in the Ottawa Valley. The winds had been freshening all day, with thunderstorms in the afternoon and into the late evening. Ominous clouds built up over the city, drifting down from the northwest along the edge of the Eardley Escarpment. It was not untypical of the summer weather in the lower Ottawa Valley, but these days, Henrietta Gertrude Rouleau read an ill wind in every day like this. Gertrude, like many mothers whose sons had left to fight in the war, dreaded the sound of an unexpected knock on her door.

Shortly after 7:30 p.m. that turbulent and unsettled evening, there was a tentative rap at the door of 114 The Driveway. We cannot be sure if Gertrude or her father answered the door, but when it was opened, a telegram messenger stood there in his uniform, and bid good evening. He sheepishly handed the telegram to whoever answered the door, anxious to leave before it was read. He had been delivering many of these over the past two years, and he knew it likely held bad news. He could never get used to it—the desperate looks, the shaking hands, the whitening of the faces. After signing for it, either David’s mother or grandfather closed the door quietly behind him and from that moment on, the suffering they had long dreaded had entered their home and would never again leave.

We cannot know how they reacted, but it was likely a night of shock and utter desperation in the Gisborne household. The telegram said only that he was missing—not where, or why or how. Just missing. It was the truth, and Gertrude and her father needed to know it, but it had to cause great confusion, sorrow, tears and deep emotions.

The very telegram that Gertrude Rouleau held in her shaking hands on the evening of 6 June 1942, given to the author by his cousin and dear friend Peg Christie—a treasured artifact that holds the tears of a gentle woman whose sacrifice was almost unimaginable. The Rouleau/Gisborne family learned that their son David was missing in action just 72 hours after he was shot down off Malta. It is a testament to how well the system worked and how much the RCAF cared about the families of their airmen, that all efforts were made to get them the news as fast as possible, regardless of the outcome. There is little in this telegram that would help Gertrude understand what had happened to her son, only the knowledge that he was missing. Scan from actual telegram

We tend to think that mothers of that period were far more stoic, less likely to be destroyed by such news than mothers today. They could not possibly have loved their children as much as we do in these enlightened times. It was a different time, we think—there was not the same connection between parents and their sons and daughters. Well, we’d be wrong about that. News that her only child was missing in action would have devastated her and broken her already wounded heart with the same ferocity and horror that we would feel at the possibility of the loss of our own children. It doesn’t take much of an imagination to understand her thoughts that terrible night.

There was hope however. He was just “missing” after all. Only one man was seen to be floating in a dinghy after the fight, but when pilots refuelled on Malta and returned to find him, there was no one to be found. Although the five remaining pilots in his ferry flight knew that David Rouleau was somewhere beneath the Mediterranean, tangled in the broken wreckage of his Spitfire, there was a process that had to be followed.

Since his death could not be confirmed, a long and prescribed step-by-step process towards presumption of death and final certification of death would keep Gertrude rattled and desperate that hope would turn to good news. It never did. Over the next year, she received a series of letters from the Casualties Office of the Royal Canadian Air Force, some by registered post. Each of these would have awakened a deep hope that good news was contained in the thin envelopes, perhaps news of David’s internment in a Sardinian prisoner of war camp. Each letter had to be yet another hot blade to the heart, but the RCAF knew it was important to go through this relentless and sorrowful process. One of these letters even asked if she had heard anything through unofficial channels, as the RCAF had no news to share. On 5 February 1943, more than eight months after David’s death, the RCAF wrote to Gertrude that he was now considered dead. In May of 1943, the RCAF prepared an internal note called “Notification of Death” in which it declared, “for official purposes”, that Rouleau was dead.

As much as the preceding year had readied her for these letters, the moment must have opened the wound once again. Since the telegram arrived those many months before, the only facts about her son’s death were related to her in a letter from the RCAF two weeks after David’s disappearance. The letter said “On that day your son set out from Gibraltar in a Spitfire aircraft and failed to arrive at his destination in Malta. It is believed that he was engaged by the enemy.” Only part of this is true, and it is likely that censors required that the details of his flight not be made public as the flights from aircraft carriers was somewhat of a secret. This however, is the only report of what happened to him that she would ever receive.

There is a word used these days in cases such as this—closure—the feeling of finality or resolution that should eventually and naturally come from a traumatic event or tragedy. This comes in the form of knowledge about the event—learning and understanding exactly what happened, how it happened, why it happened and if there was someone at fault. In the case of a death, closure also comes in the form of a body to wash, to touch, to bury. Gertrude would get none of these. Her beloved red-cheeked little boy simply ceased to exist one day—on the far side of the world and more than a year after she had said goodbye to him at Union Station. She now had nothing except his room, his old civilian clothes and some letters.

There was however the matter of his personal effects—the last remaining objects and possessions that defined him and accompanied him. Gertrude now began to enquire about the whereabouts of his suitcase, uniform clothing and the inconsequential objects that travelled with him. Rouleau’s service file contains several handwritten letters from Gertrude to the RCAF and correspondence from them concerning locating and returning the personal contents of his life. This was not to be as easy as it normally would be.

David had been in transit at the time of his death—belonging to no one, residing at no place. Upon leaving Great Britain on the freighter Empire Conrad, he brought with him all that he owned in a couple of cases and cardboard boxes. He and his fellow pilots were travelling with crated factory-fresh Spitfires, which would be offloaded on Gibraltar and assembled aboard HMS Eagle. After arriving at Gibraltar on 27 May, he would have left all of his belongings at RAF Gibraltar for transportation by a 24 Squadron Lockheed Hudson on the supply shuttle. On 2 June 1942, the day Rouleau left Gibraltar, the personal effects of all of the 32 pilots bound for Malta were flown there aboard Hudson (RAF Serial No. AE581). The following day, far to the west of Malta, 32 Spitfires succeeded in lifting off Eagle, though only 28 made it safely to Malta.

The RCAF never stopped trying to find the whereabouts of David’s belongings, but no administrative record or paperwork trail would lead to their discovery. Reading the handwritten notes from Gertrude that I found in her son’s service file, one feels her desperation to touch and cherish these last links to her long lost son. Then, on 6 June 1945, a month after the end of the Second World War in Europe, the Royal Canadian Air Force Director of Estates received a letter from RCAF Overseas Headquarters in London that “one case, one bale, one Gladstone and two kit bags, containing personal effects” had been discovered. The letter went on to explain that the items had been put into storage in the Middle East (possibly Egypt) in 1942 and “have just recently come to light. They will, no doubt, constitute those for which the next-of-kin were enquiring.”

While the RCAF was informed of the find on 6 June, Gertrude would not receive a letter until 19 September, by which time the contents had been reduced to a carton and a suitcase—likely RAF issue equipment was removed and reused, but other things contained in the original find in the Middle East would also continue to arrive later that year.

A list of David Rouleau’s personal effects found in the cartons in the Middle East. Two letters of introduction had been removed along with a pistol, a diary, a pay book and two log books. Copy of list sent to Gertrude Rouleau via Library and Archives Canada

On 24 September sometime after 11 a.m., an RCAF transport driver knocked on the door of 559 King Edward Avenue, where Gertrude now lived with her new husband, a government architect by the name of Kenneth D. Harris. She signed the delivery slip as Gertrude Rouleau, though, by now, that was likely not her name. Perhaps she did this to avoid confusion, or perhaps she did it to honour her son and David’s father, her first husband.

Having signed for the delivery, she would have closed the door and perhaps stood there for a while, contemplating what she would find. The delivery included a document listing the contents of the carton and the suitcase, which had been deposited at her feet. This would be the closest she would ever come to her son again. It must have been a profound and very difficult moment. I found a document in David Rouleau’s service file that lists the contents, likely in the order they were taken from his original cardboard boxes stored in the Middle East for three years. It’s hard to know what Gertrude had expected to find there, in those boxes, but it had come a long, long way to get to her and likely she looked at each item one by one and pulled up a memory to go with them. What stands out for me is the extraordinary ordinariness of the contents: A single penny, an elephant trinket (possibly a good luck charm), a roll of tape, an odd sock, suspenders, spoon and fork and so on—so many of the ordinary things we never think about but which we feel obligated to carry from place to place. The more ordinary the object, the more poignant the memory.

Three years and three months after her son died, Gertrude finally received a box and suitcase filled with his belongings. The emotions that must have been running through her heart and mind as she took the clipboard from the DND Estates Branch delivery man and signed her name, we can only imagine. It is interesting to note that she signed her name as Gertrude Rouleau, though the contents of the delivery were apparently delivered to the home of Kenneth Harris. Signed delivery slip via Library and Archives Canada

I can imagine (and please remember that this is just imagination—a word painting if you will) that she, and possibly her new husband, carried the carton and suitcase to the kitchen table. She would have opened the suitcase first I think, possibly seeing a gold D.F.G.R. monogram stamped into the leather. The last time she had seen it, the CNR porter had taken it from her son and carried it into the car ahead of him. For her now, the suitcase was David returned.

It is said that smells are the greatest triggers of memory, and we can all attest to that fact. A fragrant perfume recalls a passionate love; coffee, toast and cleaning products bring to mind the old office cafeteria and its friendships, and woodsmoke brings a long forgotten dream rushing back to your heart. I can see her shaking hands on the brass latches; hear the thunk, thunk as they release; and sense long forgotten memories rising like invisible incense, swirling, eddying, entering her nostrils. After a transatlantic crossing, a year in Great Britain and three years in the Middle East, it likely smelled musty, with hints of sorrow and loss. But, like a gifted sommelier, Gertrude would have been able to sort out and distinguish the smells of paper, wool, brass polish, leather and separate them from David. I can see her now—lifting in both hands his tunic with its pilot’s brevet and burying her face in it, drawing in a deep breath through her nose. It was likely the tunic he was wearing when she last saw him. Sewn to it were his pilot’s wings, something he had been so proud of when she last saw him in April of 1941. She had been so very happy for his accomplishment, yet so worried. She could see where his Flight Sergeant’s wings had been sewn, but they had been removed, replaced instead by the single narrow band of a Pilot Officer on his sleeve cuff. The letter from David telling her that he had been commissioned had reached her only a short time before the arrival of the telegram that had broken her. A couple of weeks before leaving 131 Squadron, he had been promoted. Four weeks later, he was killed.

There are many items in the list above, too many to list and speak to, but some must have been particularly heartbreaking to see, to hold, to smell. If one item held his memory more than others, I suspect it would have been his pajamas—folded, soft, comfortable, personal—likely the same pajamas he wore that last night at his grandfather’s house. As a parent, these would have been special to Gertrude for she would have understood that they had lain against his skin as he slept. One can only imagine the ghost that passed through her soul the moment she held them to her face. There were literally hundreds of items—uniform clothing for winter and summer, personal grooming items, swimming trunks, spectacles, and writing materials. There were some items that would have told a story of his past year—letters, snapshots, address book and receipts from Simpsons of Piccadilly—During the Second World War, Simpsons of Piccadilly was one of the largest stores to stock wartime uniform for soldiers, providing for both men and women officers and civilians. It is likely that David had stopped there on leave to purchase suitable clothes for life on Malta and perhaps to have his new Pilot Officer stripes sewn on. His belongings included shorts and khaki shirts, possibly purchased at Simpsons. There is no way to know for sure how Gertrude felt as she methodically lifted out all the contents of the carton and the suitcase, but I suspect it was a very sad event for her—bringing up old memories, opening old wounds.

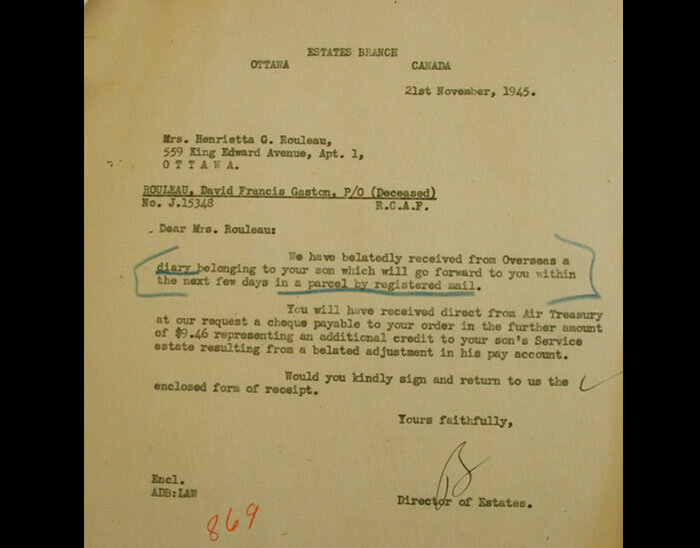

There was a diary found in the original cartons, but it was not delivered with the rest on 24 September. It would come by special delivery some two months later. Why this came later is not known, perhaps it was being studied. It must have been sad, but meaningful, for Gertrude to read her son’s words, his fears, his passions, his thoughts. Three years later, David’s log book, which had been removed from the original effects by the RAF, was returned. Both the diary and the log book have disappeared into the years since, as did Gertrude. Her father died in 1946, her husband in 1966. It is not known if the log books and diary still exist, but continued digging over many years has revealed much about David and his Mother. We will keep digging.

The story of David Rouleau underscores the terrible worry, suffering and, in many cases, ultimate sacrifice which fell upon the families of the men and women who participated directly in the war. In many respects, the families were participants in the war—not combatants, but physically invested in the service of the country, risking their most precious children, suffering long beyond the deaths of their young boys. When I first read through David Rouleau’s numerous service file documents, I saw a lingering battle between a suffering mother in search of closure and what I thought was a bureaucracy acting too slowly to help her. I read her handwritten notes and felt her desperation. I read the letters from the RCAF and I only saw platitudes written on behalf of a commanding officer that seemed to say kind things that resulted in no action. But I was wrong.

Encouraged by the much respected Canadian aviation historian Hugh Halliday to look closer at these files, to read between the lines and to understand the complexities and difficulties faced by members of the Casualties Office, the Estates Branch and the Air Staff, I began to see what he knew I would find—empathy, kindness, understanding, respect and a shared grief—in the words of the RCAF officers charged with these very difficult tasks. After rereading these letters, I began to understand that there was a process, a defined set of steps which were to be taken when a young man was lost on operations, but for whom there was no clear witness to his demise. A mother, father or wife must be told the truth, and as quickly as possible. They must not lose hope but on the other hand they also should not be given undue hope. It was a thankless task, and one of the most difficult in the service of the Royal Canadian Air Force during this time.

In the case of David Rouleau, his personal effects arrived on Malta but he never did. They were likely held on Malta briefly and then shipped back to Gibraltar and onwards to a storage depot. If he was on a squadron at the time, his mates would have packed his stuff up—leaving out the bits his family might not want to see and sharing his liquor if he had any. His belongings would be packed and sent on to his family straightaway, with a letter from his commanding officer explaining what had happened. But for this one short period of time in transit, David belonged to no one. There was a war on, and on the island of Malta, bombing often caused the loss of records, but David’s belongings did get carefully stored somewhere. They were not discarded or pilfered. They survived because the RAF and the RCAF did care. When the war was over and men somewhere in the Middle East had time to unpack the place where they were stored, David Francis Gaston Rouleau’s earthly belongings were recognized for what they were and in due course, they made their way home to Gertrude.

Dave O’Malley

Sometime in the winter of 1940–41, Gertrude’s son David poses with his flying instructor and a Fleet Finch at No. 13 EFTS, St. Eugène. Photo via Peg Christie

A photo of Leading Aircraftman David Rouleau at No. 2 Service Flying Training School at RCAF Station Uplands, Ottawa. He wears a pair of leather gloves and carries a Kodak Bantam camera. These both were mentioned in his list of personal effects. This camera was with him through his training and through a year of operations with 131 Squadron, Royal Air Force. One can only imagine what photos he took with it during his time in the RCAF. Though they were returned to his mother, they would disappear into the mists of time when she remarried and moved out of her father’s house. Photo via Peg Christie

After the initial telegram, Gertrude Rouleau received this letter from the RCAF two weeks after the death of David. It states the only information she would ever be given about the circumstances regarding the death of her only son. While it explains little, it does not yet confirm that he is dead, leaving the door open for news that he may have been captured or rescued. The RCAF would often wait months for some sort of confirmation from the Red Cross and other agencies that downed aircrew were in prisoner of war camps. Copy of letter sent to Gertrude (Gisborne) Rouleau via Library and Archives Canada

A note from Flight Lieutenant I.D. Corcoran, an RCAF Casualties Officer in Ottawa sent to Gertrude three months following David Rouleau’s Missing In Action report. Though nothing new had been learned, Corcoran was at least letting her know that “no news is good news”. The sad thing is that, upon seeing the letter in her mailbox, she likely held out hope of good news only to have her heart broken again. Copy of letter sent to Gertrude Rouleau via Library and Archives Canada

During the Second World War, the pain of learning that a loved one was possibly killed was often compounded month after month, with hope held out for survival. In this letter to Gertrude, dated 9 November 1942, the RCAF tells her that they believe that there is little hope, but they tell her also that it will still be another month before they officially say so. While this must have wounded her deeply, it likely still gave her a modicum of hope—futile as it was. Copy of letter sent to Gertrude (Gisborne) Rouleau via Library and Archives Canada

In early February 1943, Gertrude received a letter written from Air Vice-Marshal N.R. Anderson, Deputy Chief of the Air Staff, with the RCAF’s final statement about the fate of her son. She surely had been holding out hope until now that David was alive and in a POW camp. This must have been a crushing blow to Gertrude. The letter was sent “care of” Captain W.D. Burden, a family friend and a man who had written a fine letter of recommendation on behalf of David Rouleau when he enlisted in the RCAF. Records show that Burden, an Army Captain in the First World War and a Branch Manager with the Canada Life Assurance Company, had asked that letters of this type be sent to him at his home on Monkland Avenue (a few blocks from the Gisborne home) that he may deliver them in person to Gertrude—a very thoughtful gesture that guaranteed that there was someone on hand to comfort her in the event of bad news. She had been living with her father at an address only a few blocks from this address. Copy of letter sent to Gertrude (Gisborne) Rouleau c/o Captain Burden via Library and Archives Canada

By the following year, no news had been heard from or about David Rouleau. Though they did not have a body with which to confirm his death, for the purposes of closing the file, a Certificate of Presumption of Death was issued on 9 February 1943, eight months of silence having elapsed. Copy of Certificate from Rouleau’s service file via Library and Archives Canada

By May of the following year, Flight Lieutenant Milton A. Foss, the Casualties Officer for the RCAF, signed a note confirming what she had not dared to think all these months—David was now presumed and certified as dead. Foss did a tough job in tough times and his name is signed or stamped in many a letter to a mother or father. Copy of letter sent to Gertrude (Gisborne) Rouleau via Library and Archives Canada

On the 6th of June 1945, the RCAF is informed of the finding of the Personal Effects of David Rouleau, which have been in storage for more than three years. A Gladstone is a leather satchel, similar to a doctor’s bag. Copy of letter via Library and Archives Canada

By September of 1945, the widow Rouleau had met and married a government architect by the name of Kenneth D. Harris. They lived on King Edward Avenue on what was once a tree-lined boulevard. The Estates Branch still had her old name and address, but it was likely redirected there by her father who still lived at 114 The Driveway or perhaps family friend Captain Burden. The address indicated here is the home of Harris. It is doubtful that Gertrude would be living with Harris without being married, given the time and Harris’ station in life. Letters over the next year would still be addressed to and even signed with the name Gertrude Rouleau, though she and Harris were married on 30 June 1945. Copy of letter sent to Gertrude (Rouleau) Harris via Library and Archives Canada

Two months after Gertrude took delivery of David’s personal effects, she received another letter from the DND’s Estate Branch informing her that shortly they would be sending her David’s diary, which was not included in his personal effects in the first delivery. One can imagine the opening of the wound in her heart one more time, combined with the trepidation and excitement of knowing that shortly she would be reading her son’s very thoughts and actions covering the time from when he boarded the train for Halifax and the day he sailed for Malta. Copy of letter via Library and Archives Canada

The original contents of David’s personal effects included a Smith and Wesson revolver, which likely he acquired personally while with 131 Squadron. This was not standard issue for RAF fighter pilots, so it was kept back from the original delivery. Gertrude was then sent a letter asking if she cared to have this pistol, to which she replied that it was not wanted. One can imagine the horror of a Canadian woman at the sight of such a thing—so uncommon even today in Canadian households. Copy of letter via Library and Archives Canada

By May of 1946, Gertrude was now properly being addressed as Mrs. H.G. Harris. The words of Group Captain Walter Allen Dicks, a career air force administrator, showed both compassion and patriotism. The author is now proudly in possession of the Operational Wings mentioned in this letter, a gift from Peg Christie, David’s cousin and close childhood confidante. Copy of letter via Library and Archives Canada

The pain of David’s death would never go away, but it could be numbed in time. Letters such as this one three years after the war, would have brought back the pain and sorrowful memories of a beautiful son lost forever, but his log book would have been a cherished memento. I only wish that I could see the contents of this log book and follow the year of David’s life in Great Britain that heretofore has been a mystery. Copy of letter via Library and Archives Canada

One of the last letters received by Gertrude must have reopened a wound that had begun to heal, ten years after the death of her son David. The RCAF Casualties Officer, Wing Commander W.R. Gunn was particularly kind and heartfelt. It was important that David’s final resting place be certified as “no known grave” so that his name may be chiselled into the Malta Memorial. This memorial was built on a site generously provided by the Government of Malta, and commemorates those who lost their lives while serving with the Commonwealth Air Forces flying from bases in Austria, Italy, Sicily, the islands of the Adriatic and Mediterranean, Malta, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, West Africa, Yugoslavia and Gibraltar, and who have no known grave. The memorial was unveiled two years after this letter to Gertrude. There are nearly 2,300 names of airmen who lost their lives in the campaigns of the Western Mediterranean and who have no known grave—David Francis Gaston Rouleau who lived at 114 The Driveway, just a few blocks from my house, is one of them. God rest his young soul. Copy of letter via Library and Archives Canada

David Rouleau (second from left at back) was somewhat of a writer at Lisgar Collegiate High School. Here he is with the school’s yearbook staff in the late 1930s. One of the items found in his personal effects and returned to his mother after the war was a copy of The History of English Literature as well as several other books. With his year book activities, his study of the arts at University of Toronto, and these books, it seems he had a creative bent. Later, Gertrude would take receipt of a diary which was sent after she received his personal effects. I think often of what it may have contained—what the creative, lonely young man with the prematurely receding hairline may have put down on those pages. I will never know.