TWICE LUCKY – the Trevor Southgate Story

When Great Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, they were not prepared, despite the astonishingly ominous war cloud that had been hanging over Europe and moving in from the east for years. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s delusional belief that he could appease Hitler by throwing Czechoslovakia and Austria under the bus not only sacrificed these nations, but was eroding the honour and moral position of England. When Poland was attacked, Chamberlain was still hoping for a negotiated treaty. As Germany tightened its grip on Poland and then went for Norway, the British leadership was still reluctant to attack German private property such as factories and fuel storage depots.

Despite a complete lack of war leadership at the top, for most of the last half of the 1930s, there were men and women who had no trouble reading the writing on the wall. Some were Members of Parliament like Harold Macmillan, Bobby Boothby and Ronald Cartland, while others were young men in their teens, who saw that they would need to stand for something. To stand and, as MP Leo Amery so famously said in Parliament, “Speak for England”.

One such young man was George Trevor Southgate, a tall and slender 18 year old from Ealing, a suburb of West London. Enamoured of aviation, Trevor Southgate enlisted in the Royal Air Force, receiving a Short Service Commission as an acting Pilot Officer on 16 May 1938, just as Germans in Sudetenland were beginning their internal campaign that paved the way to annexation by the Nazis. Whether he had politics in mind or was just dreaming to fly, it does not matter. What matters was that Southgate was one of a new breed of young, patriotic and courageous airmen that made up the ranks of the Royal Air Force at the very moment they would be needed most.

There were many at the time who felt that the British Army and the Royal Air Force were woefully unprepared, under-equipped and undermanned. The governments of Great Britain and the Commonwealth were, at the time of Southgate’s enlistment, just beginning to consider the implications of this unreadiness and to begin planning for a possible mass induction and training of airmen qualified for combat. Even with the declaration of war and the spooling up of the colossal war training machine that was the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), no one, from Churchill on down to newly-winged Trevor Southgate, could ever have predicted the final requirement for men and machines that would be necessary to see the war to its conclusion five years later.

The BCATP, or Empire Training Plan as it was known in the Antipodes, and Joint Air Training Scheme in South Africa fed an unprecedented number of qualified aircrew (pilots, navigators, radio operators, gunners, engineers, and bomb aimers) into a war machine whose appetite for youth was insatiable. The numbers in Canada alone boggle the mind—167,000 aircrew trained, of which 50,000 were qualified pilots. Though the sheer scope of the war made the requirement for trained aircrew massive, it was the startling death toll and attrition that made the final numbers what they were. In Bomber Command alone, some 55,500 airmen were lost on operations, more than 10,000 Canadians.

For young men like Trevor Southgate, the future was most definitely uncertain, even at the time of his enlistment. He could never have known, however, the depressing odds of him surviving as a pilot until war’s end. If one factors in the theatres, campaigns and battles in which Southgate flew operationally, his odds of survival dropped considerably. Trevor Southgate would be severely injured flying during the Battle of France; survive 1942 flying in and out of Malta, the most bombed and attacked place on the planet that summer; survive the aerial terror of D-Day; survive the fiery crash of his Dakota at the catastrophe of Operation MARKET GARDEN and evade capture in Holland.

Southgate’s story is not only one of survival, but also of professionalism, duty, courage and love of flying. His role in the Second World War is, as he will likely tell you, just one of many hundreds of thousands of stories of sacrifice, skill and comradeship from that tectonic struggle. Over the years of writing down these stories, I have found all of them compelling and remarkable, but Southgate’s is rare in that his operational flying spans the whole length of the war, from before hell broke loose until after it had been put down. In that time, he found himself in the thick of it, flying aircraft with no defensive or offensive capabilities whatsoever.

Most pilots who earned their wings went on to operational flying in only one aircraft type, at the most three. A pilot might learn to fly only the Halifax and perhaps transition to the Lancaster, or he might start on the Hurricane and then move to the Spitfire and then by war’s end, the jet-powered Gloster Meteor. Trevor Southgate became a generalist—able to fly a wide assortment of aircraft, many of which were uncommon in the RAF. In addition to time on single-engined trainers and fighters, Southgate would build substantial time on 12 different types of single and multi-engined aircraft—from the four-engined de Havilland Express biplane to the diminutive Percival Vega Gull to the heavy Douglas DC-3 Dakota and Lockheed Hudson. Above all, it is his two brushes with death that define and bookend his astonishing career—one in the opening salvos of the war and the other four years later as the enemy was reeling backwards into the fatherland.

Trevor Southgate began his flying training at RAF Yatesbury in Wiltshire, flying the de Havilland Tiger Moth at No. 10 Elementary (and Refresher) Flying Training School (ERFTS). After soloing and gaining a very typical 97 hours on Geoffrey de Havilland’s little trainer, he was given an Acting Pilot Officer’s commission with a one year probationary period. From Yatesbury, he was sent to RAF Montrose in Scotland for his Service Flying Training, where he learned to fly much more powerful Hawker Hart, a former light bomber of the RAF in the inter-war period, now used primarily for training purposes. Its complex Rolls Royce Kestral engine and high performance envelope made it an excellent advanced trainer. At Montrose, Southgate flew more than 200 hours in the Hart and earned his coveted Royal Air Force pilot’s wings.

An innocent-faced George Trevor Southgate (left) and former public school chum Stuart Trotter learn to fly on de Havilland Tiger Moths with the Royal Air Force at RAF Yatesbury in Wiltshire—an experience not unlike learning to fly in Canada—cold and wet. Photo: Trevor Southgate Collection

A photo of Tiger Moths in 1938 at RAF Yatesbury, home of No. 10 Elementary (and Refresher) Flying Training School (EFRTS) – the time, place and machine of Southgate’s initial flight training. Photo: Terry Fox - Air Britain

Trevor Southgate poses for a photo prior to a mess dinner at RAF Uxbridge, shortly after completing his elementary flying training on Tiger Moths at Yatesbury. Unlike the wartime RCAF where a cadet pilot would carry the rank of Leading Aircraft Man until he received his wings after Service Flying Training, the stripe on his cuff indicates that Southgate was promoted to Acting Pilot Officer on 16 May 1938. This came with a 1 year probationary period. The following 16 May 1939, Southgate was appointed to a full non-probationary rank of Pilot Officer. Photo: Trevor Southgate Collection

Related Stories

Click on image

At Number 8 Flying Training School (later No. 8 Service Flying Training School) at RAF Montrose, the Hawker Audax (similar to the Hawker Hart which he also flew at Montrose) was used for advanced wings-grade flying training. Here we see a young Pilot Officer (Acting) Trevor Southgate standing proudly in 1938 before an Audax, the aircraft he would soon win his wings on. More than 800 pilots, including a number of the RAF’s leading aces of the war, received their wings at Montrose from 1936 until 1942, when the school closed down. These names include Canadian uber-ace George “Buzz” Beurling as well as Irishman Brendan “Paddy” Finucane and New Zealander “Cobber” Kain. More importantly, this was the home of 612 City of Glasgow Squadron and our own Warrant Officer Harry Hannah, to whom our Boeing Stearman was dedicated. Photo: Trevor Southgate Collection

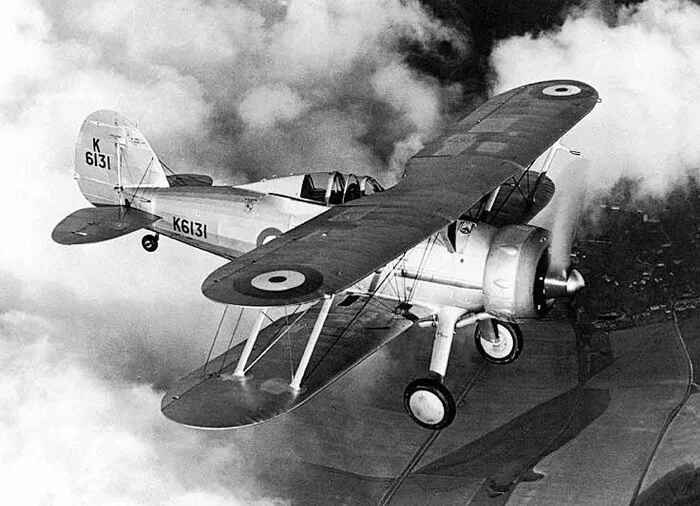

Trevor Southgate earned his coveted RAF pilot’s brevet on the Hawker Hart/Audax, two variants of the same aircraft of the last group of high performance biplanes in the service of the Royal Air Force. The Hawker Hart was a British two-seater light bomber aircraft of the RAF. It was designed during the 1920s by Sydney Camm, the future designer of the Hurricane. The Hart was a prominent British aircraft in the interwar period, but was obsolete and already sidelined for newer monoplane aircraft designs by the start of the war. RAF Photo via HawkerHind.com

At RAF Montrose, Southgate (right) and an instructor by the name of Buttery prepare for a cold weather (typically Scottish) flight in a Hawker Hart or Audax. Photo: Trevor Southgate Collection

By now a seasoned pilot with 24 Squadron, Trevor Southgate, having flown in a Gloster Gladiator, was the centre of attention and the focus of good natured ribbing with these cadets at RAF Hendon. The photo appeared in an English newspaper in February 1941. The caption beneath the photo reads: “Their hero: An R.A.F. fighter pilot is every cadet’s ideal—and they’ve plenty of questions to ask him. The reason that the pilot looks bewildered is that he doesn’t know the answer to this one. So the boys have a laugh on their hero. The country’s future depends upon the immediate raising and training of like-minded lads like these, and they have answered the call in such vast numbers that there is ample reason to face the future with complete confidence.” The adulation on the faces of these boys is a powerful message about the inspirational draw of aviation in those days. Sadly, there was no thought given to the fact that some of these young boys would be dead by the end of the next four years. Photo: Trevor Southgate Collection

Trevor Southgate looked every inch a hero to the young Hendon cadets in the previous photo as he stood in front of his Gloster Gladiator. Southgate qualified on several single-engine fighters from the Gladiator to the Spitfire. By the time he was regaling the cadets at Hendon, the Gladiator (above) was used largely for advanced single-engine training, having by then become obsolete at the front. Photo: Wikipedia

Most young pilots, recently graduated from flying training, longed to fly fighters like the Supermarine Spitfire or Hawker Hurricane, the latest front line fighters of the day in 1939. Or, if they were not chosen to fly a single seat fighter, then perhaps a light bomber/night fighter like the Bristol Blenheim or Vickers Wellington. For Trevor Southgate, that was not to be. Instead, he found himself with one of the oldest units in the RAF—No. 24 Squadron, in the First World War a fighter unit, but now a VIP, ambulance, liaison and utility squadron. Likely, Southgate was initially disappointed with his appointment, but it would soon be clear that 24 Squadron could find itself in the thick of things indeed. Flying for 24 Squadron and its offspring, No. 512 Squadron, put Southgate at the very centre of both politics and war, as we shall find out.

Though 24 Squadron had disbanded after the end of the First World War, it was reformed in 1920 with a theretofore unique task—the transport by air of military and government VIPs. Until the creation of the King’s Flight in 1936, it was the duty of 24 Squadron to move the Royals about the country by air. At the outset, the squadron utilized military type aircraft, but soon began to acquire civilian designs that were more suited to comfortable travel or spacious interiors. When war broke out, the squadron also pressed into service civil-registered aircraft to supplement their fast growing trade.

During his service with 24 Squadron, Trevor Southgate flew many aircraft types from the 17,000 lb DC-3 to the diminutive 1,700 lb Percival Vega Gull (above) and its more common cousin, the Percival Proctor. Only 90 Vega Gulls were built as opposed to the 16,079 DC-3s and variants. Early constructed Vega Gulls were used in many air races and record attempts in the “Golden Age of Aviation”. 15 Gulls were ordered for the RAF, with 11 serving with Southgate’s 24 Squadron. The Gull was used for liaison flights and pilot repositioning—similar to the flight in which Southgate was shot through the back. Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum

Trevor Southgate’s squadron supplied a detachment to France in the spring and early summer of 1940 to operate a courier service from bases and front line airfields. Young Pilot Officer George Trevor Southgate was one of the pilots who flew despatches and VIPs around the theatre. But as France collapsed in upon itself under pressure from the German Blitzkrieg, the courier role quickly devolved to a rescue and evacuation task. British troops were withdrawing to the northwest, columns of men and equipment heading toward Dunkirk. RAF forward airfields were quickly abandoned and the support units flown home or forced to join the exodus to the Belgian coast.

It was at this time, just one week before the evacuation at Dunkirk got underway, that George Trevor Southgate first escaped death at the hands of the enemy. Southgate was piloting a Percival Vega Gull, transporting three other RAF pilots from Échemines to Reims, France about 270 kilometres to the southeast of Dunkirk [The airfield of Échemines, to the east of Paris, was where, two weeks later, the great New Zealand ace, Flying Officer Edgar “Cobber” Kain (16 victories), was killed, stunting his Hurricane before heading home to England]. The former French fighter base at Reims-Champagne had been used by units of the RAF’s Advanced Striking Force—with Hurricanes and Fairey Battles. It was also used by a detachment of 24 Squadron. An RAF Hurricane squadron, in the path of the oncoming Germans who were pushing the Allies towards the Belgian coast, was forced to abandon three Hurricanes at Reims and Southgate was bringing the pilots there to ferry the aircraft to safety.

A Percival Aircraft Co. Vega Gull liaison aircraft in Royal Air Force all-silver livery. Southgate’s 24 Squadron, originally formed during the First World War as a fighter squadron, was reformed in 1920 as a VIP transport unit. During the Second World War, 24 Squadron operated the Vega Gull as well as the Lockheed Hudson, Avro York, de Havilland Flamingo and Dragon Rapide, Douglas C-47 Dakota, Airspeed Oxford and a myriad of very strange and exotic types. Photo: RAF via the Don Shumaker Collection, posted on 1000AircraftPhotos.com

24 Squadron operated two types of Percival light aircraft—the Vega Gull and the Proctor. While the Vega Gull had a meagre production run of 90 aircraft, more than 1,100 copies of its follow-on cousin, the Proctor, were built. Trevor Southgate flew them both. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Overflying the city and approaching the airfield at Reims-Champagne, the tiny four-seat Percival Vega Gull was hit by ground fire and Southgate in the left pilot’s seat was struck by a bullet that travelled through his back, knocking him unconscious and he slumped over the controls. As difficult as the situation was, he was lucky to have three RAF pilots on board—Pilot Officer Kenneth Smales, Aide-de-camp to Air Officer Commanding the Advanced Striking Force, as well as two Squadron Leaders—Dick Collard and a fellow named Budd. Collard in the seat behind Southgate managed to pull him off the controls and Smales was then able to use the dual controls to land the aircraft safely at a place named Villeneuve. Still unconscious, Southgate was whisked away in a 24 Squadron aerial ambulance to hospital, where he would recover from his wounds.

It wasn’t until many years later that Smales and Southgate would make contact again, long after retirement. The following two letters from Group Captain (Ret’d) Ken Smales, helped put all the pieces together for Trevor Southgate. The first was a letter from Smales looking to find out what had happened to that young pilot who he last saw in the late spring of 1940. The second, a follow-on letter detailing what had happened to him. At the time, both men were living in England.

1st May, 1997

Dear Mr. Southgate

This is a voice from the past, long past!

I happened to be talking to Air Commodore John Mitchell the other day. He had served in 24 Squadron and in conversation, the incident which occurred at Reims Champagne airfield, 18 May, 1940 came up.

John Mitchell cave me the address of David Burgin of the 24 Squadron association of which you and he are members and that is how I found your address.

I hope you are the right person. If so, you flew me (Pilot Officer ADC to AOC AASF) and two squadron leaders, Dick Collard and Budd, from Échemines to Reims in a Vega Gull for us to collect three Hurricanes which had been left behind by the outgoing fighter squadron in the path of the German army’s advance.

You, if it is indeed you, were shot in the side of the chest and knocked unconscious. Collard pulled you back so that I, who was in the right hand seat, was able to take off downwind, using the left hand seat stick and throttle and the dual rudder bar.

We landed at Villeneuve and you were put into a 24 Squadron DH.89 to be flown, still unconscious to hospital in Paris.

That is the last I heard of you and ever since I have been on the lookout to see whether you survived and, if so, what happened to you.

Dick Collard became an MP [Member of Parliament-Ed] but died some time ago. I have not heard of Budd.

I would be delighted if you would get in touch with me and tell me what you remember of the incident and how you fared afterwards.

Yours sincerely

Ken Smales

P.S. I do hope you will not mind my contacting you like this.

Group Captain Smales had a response in just a few days.

6 May, 1997

Dear Mr. Southgate

Thank you for your letter of 3rd May.

It was good to learn that you had survived your wound so well and, I hope, have had no ill effects since. As you say, we were all very lucky.

To answer your questions. We were shot at from the ground from your left by a machine gun of some sort just as you were touching down. Just previously I had heard what I thought was the curtain expander wire vibrating. It was in fact the sound of the distant machine gun and then out came the glass windows and you were hit.

No one else was injured but the port fuel tank was punctured and one of the tyres was flat, among other damage. This latter damage was caused after we were airborne.

After you had been loaded on top “Pop” Reid’s DH89 we sat down to lunch with the Hurricane squadron (I forget the number) in the open air of that fine summer. Shortly, Hank More, the Squadron Commander came up behind me and said “Smales, you are improperly dressed”. Being a very G.S. [not sure of the meaning-Ed] young officer I stood up and asked why. He replied “Take off your tunic”.

Then I saw that the stuffing of both shoulders was hanging out with a burnt line across the back. Later I found that my shirt was also damaged and there was a red line across the skin of my back.

Whether this was done by the bullet which went through you first or another it is hard to say.

I have never found out whether the firing was done by the advance guard of the Wehrmacht or by jittery Frenchmen, but I do not think the Headquarters was keen to go into the matter of putting at risk a Vega Gull and pilot with three staff officers. Confusing period!

It would be interesting what, if anything, the 24 Squadron Operations Record Book [ORB - Ed] has to say for that day.

If you are ever in this area please do ring up and my wife and I would be glad if you would have lunch with us.

Yours Sincerely

Ken Smales

Ken Smales would go on to survive two full tours with Bomber Command, being awarded the Distinguished Service Order and the Distinguished Flying Cross. Smales died at age 88 in October of 2005. His lengthy obituary in The London Telegraph made mention of the incident with Southgate—“After the German blitzkrieg of May 10 1940, the AASF headquarters was constantly on the move. Smales was sent to an abandoned airfield near Rheims to recover some Hurricanes which had been left behind, but the light communications aircraft transporting him had to land after it was hit by machine-gun fire, injuring the pilot.

Smales, however, immediately grabbed the controls by leaning over the unconscious pilot and took off again. Despite two flat tyres and a major petrol leak, he managed to land at an Allied airfield. Smales and a comrade then commandeered another aircraft, which they flew to an airfield near Brest. There they took two motorcycles, on which they finally made it to the port, escaping in one of the last ships to leave.”

Smales’ suggestion that the 24 Squadron ORB for May of 1940 might have an entry regarding the incident led me to the British National Archives, which, for a small fee, allows you to download the Operation Record Book for a particular time period and a particular squadron. Sadly, there was no mention in this document of the incident, the Percival Gull’s flight, its passengers or the air ambulance evacuation. Looking at the ORBs (there were two separate documents for May 1940), I can see all the activity centred on their home airfield of Hendon. It is likely that the 24 Squadron courier detachment at Reims-Champagne kept a separate ORB of their activity while in France and that this was either lost or not part of the searchable 24 Squadron archive. As Smales said... It was a “confusing period”.

After Southgate’s convalescence, he rejoined his 24 Squadron at their home airfield at Hendon. Hendon, an airfield in the outskirts of London itself, was a well situated hub for 24 Squadron’s VIP and Liaison duties for much of the next two years. Here, Southgate would qualify on many types of aircraft and fly many of the leading Allied statesmen and military commanders. Handwritten notes in his logbook show that even before his near-death flight in France, he had flown Air Chief Marshal Robert Brooke Popham, at the time (late 1939) the Royal Air Force’s head of the training mission to Canada and the man who oversaw the building, manning and organization of such RAF flying schools in Canada as No. 34 EFTS Assiniboia, Saskatchewan and No. 32 EFTS Bowden, Alberta.

After rejoining his squadron at Hendon, he flew numerous dignitaries in and out of London, including Air Marshal William Mitchell, Inspector General of the RAF; General Frederick Pile, Commander Anti-aircraft Command; Air Vice-Marshal E. Leslie Gossage, Deputy Director of Intelligence and chronicler of the history of the RAF before the war; Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff; Anthony Eden, Secretary of State for War and future Prime Minister; Vice Admiral Lumley Lyster, Fifth Sea Lord and architect of the Battle of Taranto; Air Commodore Victor Goddard, Chief of the New Zealand Air Staff; Soviet General Fillipp Golikov, Head of the Soviet Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU), Marshal of the Royal Air Force Hugh “Boom” Trenchard, father of the Royal Air Force and Robert “Bobbety” Salisbury, Viscount Cranborn, a key political player and Tory rebel who helped bring down Neville Chamberlain and put Churchill in his place.

To squire these dignitaries and commanders around Great Britain, Trevor Southgate flew in a wide assortment of Royal Air Force aircraft including the Percival Vega Gull, de Havilland DH.89 Dragon Rapide, Lockheed 10 Electra, de Havilland DH.95 Flamingo, de Havilland DH.86 Express and Lockheed Hudson, Douglas DC-3 Dakota and Avro Anson. The flying was not only varied, but it was prodigious—614 hours on the Hudson alone and 517 on the Dakota.

The pretty de Havilland DH.95 Flamingo, a high-wing, twin-engined monoplane passenger airliner of the Second World War period (also used by the Royal Air Force (RAF) as a troop carrier and for general communications duties) was one of the rare types on Trevor Southgate’s list of aircraft flown. Flamingo R2765 was, like many of the aircraft of 24 Squadron’s VIP service, given a name—in this case, Lady of Hendon. Photo: RAF

De Havilland Flamingos of No. 24 Squadron RAF at Hendon, Middlesex. In the foreground, an advance party of Russian officials disembarks from R2765 Lady of Hendon to be greeted by senior RAF officers and representatives of the Foreign Office, having been flown from Prestwick in order to prepare for the forthcoming visit to London by the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, V.M. Molotov. Parked in the background is R2764 Lady of Castledown, which perished the following day while undertaking a similar mission from Prestwick to Hendon. The aircraft caught fire and crashed near Great Ouseburn, Yorkshire, killing the crew and all six members of the Russian party on board. Although suspicions of sabotage were voiced at the time, it appears that a cylinder head in one of the engines broke away accidentally in mid-air, causing an engine fire and the loss of one of the wings. Photo and text via Imperial War Museum

24 Squadron Flamingo (R2766), Lady of Glamis, flies majestically over England. Only 14 of the lovely all-metal aircraft were built, nearly all in the service of the RAF. Lady of Glamis was originally part of the King’s Flight. Photo: Imperial War Museum

For much of his RAF service, Trevor Southgate was with the legendary 24 Squadron which, as it grew in size and importance, spun off both 510 and 512 Squadrons of the RAF. The home airfield of 24 Squadron’s central elements was RAF Hendon (above), one of the most important aerodromes in Great Britain. Located in North London, Hendon today is the home of the Royal Air Force Museum, one of the finest museums on the planet. Photo: RAF via Imperial War Museum

Trevor Southgate’s list of some of the VIPs he flew included two flights in the DH.95 Flamingo with Field Marshal Alan Francis Brooke, first Viscount Alanbrooke, KG, GCB, OM, GCVO, DSO and Bar, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and Churchill’s most trusted advisor. Photo via German Wikipedia

The de Havilland DH.95 Flamingo was a pretty bird. Here, RAF AE444, (eventually Lady of Aye), wearing De Havilland test number E16, demonstrates single engine performance with its port Bristol Perseus feathered. This aircraft (E16) was the type test bed. Photo: RAF from the Ron Dupas Collection posted on 1000AircraftPhotos.com

Whilst with 24 Squadron, Flight Lieutenant Trevor Southgate flew a wide assortment of transport aircraft, including the Art Deco-styled biplane transports of de Havilland—with nearly 300 hours total piloting time in the types (DH.84 Express, DH.86 Dragon, and DH.89 Dominie (Dragon Rapide)). The DH.89 Rapide and Dominie were used for both ambulance duties and VIP transport. Here we see DH.89 RAF Z7258 Women of the Empire and RAF Z7261 Women of Britain flying low over Hendon, Middlesex, the day before they were presented to No. 24 Squadron RAF by the “Silver Thimble Fund”. Originally civilian aircraft, Z7258 (formerly G-AFMH) and Z7261 (G-AFMJ) were impressed for the RAF in July 1940. Photo: Imperial War Museum

On the ground at RAF Hendon, DH.89s Women of the Empire and Women of Britain present themselves for photographers. The DH.89 was known as the Rapide in civilian service and Dominie in the Royal Air Force. The RAF’s Hawker Siddeley HS125 jet transport of today is also called the Dominie. The word Dominie is a Scottish term for a schoolmaster. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The Lockheed 10 Electra (RAF serial W9104) served with 24 Squadron on VIP duties. The aircraft was delivered new with British civil registration G-AFEB in 1938, but at war’s outbreak was impressed into service with the Royal Air Force on 12 April 1940, as were three others (G-AEPN (W9105), G-AEPO (W9106) and G-AEPR. W9104 was damaged beyond repair on 12 October 1941, just three months after Trevor Southgate flew Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden and his wife Clarissa aboard a Lockheed 10 from Hendon to the city of York. W9105 was also lost the year before—in an air raid on Hendon in November 1940. Southgate flew 117.25 hours in command of the Electra. Photo via Wikipedia

Piloting a Lockheed 10 Electra, Trevor Southgate flew the British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden and his wife Anne Clarissa from Hendon to York on 7 July 1941. The sartorial Eden, with his signature Homburg hat, and his wife were the 1930s equivalent to Jack and Jackie Kennedy. Idolized by all of Britain, he was a softly outspoken opponent of appeasement of Hitler. He was the first choice of Tory rebel MPs who risked their political futures to remove the Nazi-appeasing and tyrannical Neville Chamberlain. Still, when he had the chance to speak up for the ouster, he wavered and declined the limelight. In the end, Winston Churchill, also a reluctant rebel and member of the Chamberlain cabinet, was pushed forward to replace the disgraced and marginalized Prime Minister. Lucky for England. Eden would remain as Foreign Secretary throughout the war and eventually become Prime Minister. His premiership lasted only 2 years, with the man impaling himself on the Suez Crisis. Photo via LynneOlson.com

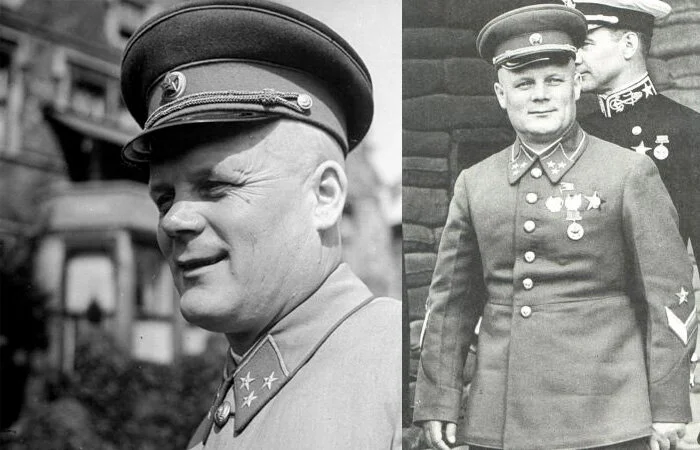

On 7 September 1941, Trevor Southgate took Russian General Fillipp Golikov on a flight from Prestwick, Scotland to London in a 24 Squadron Lockheed 10 Electra. Golikov, one of the most decorated and tough Soviet leaders of the Second World War, was in London for talks with the Allies concerning operations against the Germans. Just two weeks before, the Soviets had been an ally of the Nazis, having shared in the spoils of the invasion of Poland, but on 22 June, the Germans opened Operation BARBAROSA, an all-out assault on the Soviet Union along a wide front. The Soviets went from possible future enemy to important ally literally overnight. Photos: herdeirodeaecio.blogspot

The ill-fated Lockheed 10 Electra, W9104, of No. 24 Squadron RAF, taxiing on an airfield in the United Kingdom. Formerly G-AFEB of British Airways Ltd, this aircraft was impressed into the RAF and delivered to No. 24 Squadron on 18 December 1939. It was struck off charge after a landing accident at Clifton, Yorkshire, on 12 October 1941. Photo via Wikipedia

Douglas DC-3 Dakota Mk I, (RAF serial FD772) ZK-Y of 24 Squadron parked in dispersal at RAF Hendon, Middlesex, the home field of Southgate’s squadron for much of the war. This was the fifth Dakota delivered to the RAF, and like nearly all 24 Squadron aircraft, wears a dedication on its nose—Windsor Castle. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The Airspeed Envoy and its follow-on development, the Oxford, were twin engine light transport aircraft—both were used by 24 Squadron for liaison and ambulance duties. Trevor Southgate flew both types with 24 Squadron—22.5 hours in the Oxford and .5 hour in the Envoy. Here we see an Oxford Mark II, (RAF serial P8833), known as Nurse Cavell of the Air Ambulance Unit (operating within No. 24 Squadron RAF), on the ground at RAF Hendon. I include this photo for the interesting background behind her name—Nurse Cavell. Edith Louisa Cavell (4 December 1865 – 12 October 1915) was a British nurse. She is celebrated for saving the lives of soldiers from both sides without discrimination and in helping some 200 Allied soldiers escape from German-occupied Belgium during the First World War, for which she was arrested. She was subsequently court-martialled, found guilty of treason and sentenced to death. Despite international pressure for mercy, she was shot by a German firing squad. Her execution received worldwide condemnation and extensive press coverage. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Whilst serving with 24 Squadron, Southgate flew single, twin and four-engined aircraft, including the DH.86 Express. Essentially a four-engined sister of the de Havilland Dragon, the early production models of the Express had stability issues which resulted in several fatal crashes. In this Royal Air Force photo, we see the snug cockpit arrangement of the Express. The type saw military service with the RAF, Royal Navy, RAAF and RNZAF. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Southgate flew a number of de Havilland types, including the elegant looking, but somewhat maligned, four-engined DH.86 Express. Flying the Express, his VIP passenger manifest included such luminaries as Lord “Boom” Trenchard and Field Marshal Allan Brooke. Here, we see a 24 Squadron DH.86 Express awaiting the imminent arrival of British Army brass including the Commander-in-Chief, Scottish Command at RAF Lerwick. Photo: Imperial War Museum.

Hugh “Boom” Trenchard (left, seen here with Field Marshal Montgomery) is often described as the Father of the Royal Air Force. Learning to fly before the beginning of the First World War (his aviator’s certificate numbered 250), Trenchard rose to become Chief of the Air Staff by war’s end. He presided over the formation of the Royal Air Force in 1918, and commanded it for the next 12 years. He earned the sobriquet “Boom” for his loud, booming voice. By the Second World War, he was largely marginalized, being offered, but not accepting positions such as oversight of the BCATP in Canada or the task of camouflaging Great Britain. He was also offered responsibility for Air, Land and Sea forces for Great Britain should the Germans invade. Trenchard replied that this would mean he should have the powers of the Deputy Minister of Defence, which infuriated Churchill. Churchill then offered him the responsibility for reorganizing Military Intelligence, which he also declined. In the end, the stubborn Trenchard had manoeuvred himself from any real power in the war machine and spent the rest of his war years as de facto RAF ambassador and Inspector General. Regardless, he was considered RAF Royalty by his men and was accorded great respect. To fly him, as Trevor Southgate did, was an honour. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The last of this incomplete list, “Bobbety” Salisbury, was flown by Southgate from Gibraltar to Hendon in a 24 Squadron Lockheed Hudson in August of 1942. During that summer, 24 Squadron was very active, flying passengers and cargo into Gibraltar and on into Malta at a time when to fly to that beleaguered island was to fly a gauntlet of German and Italian interceptors or to be bombed while on the ground there. It was a particularly deadly place in the summer of 1942 and for the RAF, it was without a doubt the focus of its energy as it pushed the limits of technology and supply to keep the strategic island from falling into enemy hands.

I mention this because it is here, at this point in time, that Trevor Southgate’s story hauntingly intersects with another story which I had written some years ago – All the Things Never Done – the Last day of David Rouleau’s Life. Pilot Officer David Francis Gaston Rouleau, a young Ottawa man who grew up just blocks away from my home, was a Spitfire pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force. On 3 June in the summer of 1942, Rouleau and eight others took off from the Royal Navy Carrier HMS Eagle, attempting to make their way to Malta to reinforce with their lives and resupply, with their Spitfires, that besieged island nation. Rouleau never made it. On that morning, with Malta in sight, they were set upon by a Luftwaffe fighter squadron led by German uber-ace Gerhard Milchalski. Four of the nine Spitfires, including that of Rouleau, were shot down. None of the four pilots survived. They were the only pilots to die trying to get to Malta by flying off an aircraft carrier that summer.

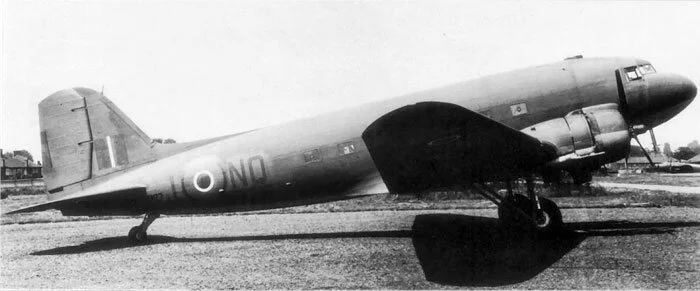

On the day before (2 June) Pilot Officer Rouleau attempted to reach Malta in his Spitfire, his belongings, which had made the journey to Gibraltar with him aboard the freighter Empire Conrad, were brought to the airfield at Gibraltar and loaded with others aboard a 24 Squadron Lockheed Hudson, RAF Serial No. AE581. The aircraft bore the squadron code ZK-L, and in the tradition of most of 24 Squadron’s aircraft, bore a dedication on its nose—Spirit of Tobruk II. As the luggage, other cargo and a few passengers were loaded aboard that fine summer morning on The Rock, the now Flight Lieutenant Trevor Southgate and his crew (Flight Sergeant Newton (second pilot), Sergeant Ayers and LAC Gregory (mechanic)) walked out and boarded the camouflaged Hudson.

Searching the internet for hours, I could not find an image of a 24 Squadron Hudson and in particular AE581 – except this screen capture of the Spirit of Tobruk II from a Pathé News reel. Apologies for the quality. Photo: Via Pathé News

According one of three 24 Squadron ORBs covering the month of June 1942, Southgate and his crew had left RAF Hendon aboard Hudson AE581 the previous day, 31 May, at 1300 hours, landing at RAF Portreath at the very southern tip of England, near Land’s End. They carried 918 lbs of freight and five passengers. They overnighted at Portreath and had the aircraft in the air by 0300 hrs the following morning, flying toward the sunrise, landing at RAF Gibraltar (North Front) shortly after 1000 hrs on the morning of 1 June. At 1510 that same day, they began a series of shuttles to Malta and back to Gibraltar, carrying passengers and baggage in both directions. By 7 June, they were back at Hendon, lucky to have not been caught by Milchalski’s “Piq-A’s” as they shuttled in and out of Malta.

Sadly, by the time Rouleau’s belongings were off-loaded in Malta, he was somewhere at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea. The Royal Air Force took great pains to record and store many seemingly inconsequential bureaucratic minutia for all theatres. Many years ago, while researching the service file of David Rouleau, I followed a sad tale of correspondence between Rouleau’s widowed mother as she sought to retrieve the personal effects of her only child. The fact that his possessions had travelled with Southgate and been delivered to Malta though Rouleau did not make it, caused some confusion. Gertrude Rouleau’s pleas to find his effects bounced around RCAF and DND headquarters as they attempted to track down where the bags had gone.

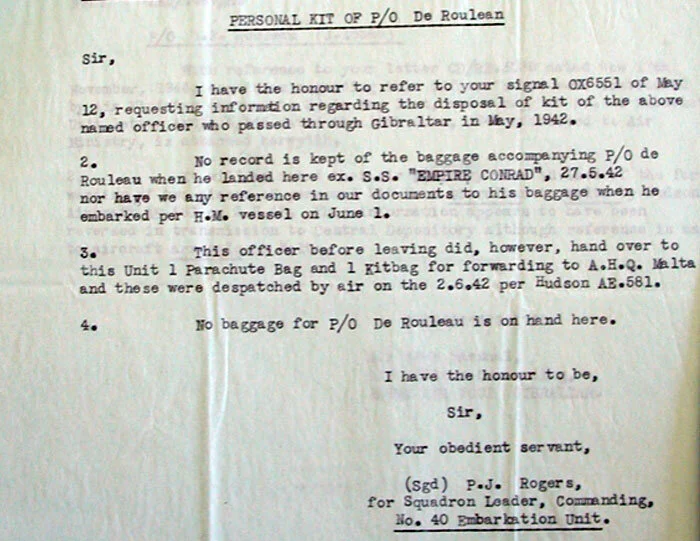

A portion of the letter to the Under Secretary of State, Air Ministry relates the slender yet haunting connection between David Rouleau and Trevor Southgate. Though the writer, Sergeant P. J. Rogers spelled David Rouleau’s name as either De Roulean or De Rouleau, this is in fact David Francis Gaston Rouleau of Ottawa. Source: Library and Archives Canada

One letter written to the Under Secretary of State, Air Ministry, London from No. 40 Embarkation Unit at Gibraltar, dated 15 June 1944, gave a clue as to the whereabouts of her son’s kit. The words “This officer before leaving did, however, hand over to this Unit 1 parachute bag and 1 Kitbag for forwarding to A.H.Q. Malta and these were despatched by air on the 2.6.42 per Hudson AE.581” forever link David Rouleau, who would never see Ottawa again to Trevor Southgate, who nearly 70 years later would come to live and retire in Rouleau’s hometown.

In 1946, Gertrude would finally have her son’s kit and other personal effects delivered by courier to her door. The list of its contents is heartbreaking. I can only imagine the poor woman holding his shirts and smelling the last tendril of connection to the lost love of her life. This list of personal effects will be the subject of a story later this winter.

Trevor Southgate would continue to fly in and out of Gibraltar and Malta as well as a myriad of other airfields in Great Britain and in various types of aircract for the rest of 1942 and on into 1943. His last flight into Malta was 14 July 1943. By this time, Southgate was flying the DC-3 Dakota which began its service with 24 Squadron in 1943. By the end of 1942, the squadron was getting very large and spread out, with routes extending as far as India. It was decided in October of 1942 that the internal communication flight would split off to form 510 Squadron, and then, on 18 June 1943, a second spinoff squadron was formed—No. 512 Squadron. Many of the Dakota crews from 24 Squadron formed the nucleus of the newly minted unit, which would soon prove its mettle in combat. Trevor Southgate joined 512 Squadron from 24 Squadron about two months later. Following his move to 512, Southgate would now fly only the DC-3 Dakota and would amass almost 600 “Dak” hours before demobilization.

A photo of a 512 Squadron Dakota shows it still with its 24 Squadron code NQ-1. 24 Squadron Daks would form the nucleus of 512 Squadron in June 1943. This particular Dak was lost at sea en route from Lyneham, England to Gibraltar on Christmas Day, 1943. Photo via incidentessgm.blogspot.ca

But Southgate’s war was far from over, in fact the most difficult and dangerous operations still lay ahead. For the next months, 512 and Southgate flew supply operations from Hendon, where the spinoff squadron remained for the time being. From London, they flew in and out of Gibraltar and Algeria in support of the ongoing campaign in North Africa. The Daks also flew long distance routes to the Azores and to India. By this time, Southgate was now an Acting Squadron Leader and this was made permanent on the first day of 1944—exactly 70 years ago today. On that same day, he was cited in the London Gazette, having been awarded the Air Force Cross. The citation accompanying the award read: “This officer has completed 19 flights to Malta on the United Kingdom–Gibraltar–Malta service. Squadron Leader Southgate is an efficient and capable pilot and has for some time been flight commander of ‘C’ Flight which operates the overseas service. Its flights have always been performed with great consistency. Throughout the period of the Battle of Malta this officer rendered outstanding service and displayed marked devotion to duty.” A month later 512 Squadron moved from RAF Hendon, where Southgate had spent the last 5 years. The squadron was transferred to No. 46 Group at RAF Broadwell, to become a tactical Dakota squadron and start training for glider towing and parachute dropping.

Southgate and his 512 Squadron mates and aircrews began training in earnest for the inevitable—the amphibious and airborne assault of German occupied France. For many months, equipment and tactics had been developed for the airborne assault. New types of large troop and equipment carrying combat gliders like the Airspeed AS.51 Horsa and Waco CG-4A Hadrian were being built and delivered to training airfields across the south of Great Britain. DC-3 and C-47 equipped squadrons of the RAF and USAAC were beginning the training process that would lead to the world’s largest amphibious and airborne invasion in history—Operation OVERLORD or, as most know it, D-Day.

A Douglas DC-3 Dakota of No. 512 Squadron, RAF Transport Command, being refuelled from an AEC Type ‘A’ petrol tanker while in transit at Lagens Airfield in the Azores. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Flying a heavily armed and armoured Hawker Typhoon or a machine-gun bristling B-17 Flying Fortress on D-Day takes courage enough, but imagine the massive steel-reinforced balls it took to fly at just above 130 knots, completely unarmed and unable to avoid flak, on a straight line whilst towing a heavy, equipment-laden glider amidst many others doing the same—in broad daylight! On the night of 5/6 June 1944, Squadron Leader Trevor Southgate and his 512 Squadron crew (Aircraft KG390—Flight Lieutenant Albert Saunders, Flight Lieutenant Bryant, and Flying Officer Joseph Perry) took off at 2320 hrs and dropped a stick of 20 airborne soldiers behind enemy lines as part of Operation TONGA. He then turned around and flew back through waiting flak to land at 0250 hrs at Broadwell where, later that day, he hooked up a Horsa Glider. He then, as part of Operation MALLARD, towed that glider back to Normandy that evening, where by now, the enemy was surely waiting.

To fly at such slow airspeed and at such low altitude through flak and ground fire is akin not to running a gauntlet, but to walking it... very slowly. Southgate and his crew earned their bacon and eggs after returning safely to Broadwell at the end of the 6th after two operations in support of D-Day.

The morning after Operation MALLARD in which Trevor Southgate participated along with his Dakota crew and others of 512 Squadron, is depicted in this oblique photographic-reconnaissance vertical, taken from 800 feet, showing part of Landing Zone ‘N’, north of Ranville, Normandy, on the day following the airborne landing of the 6th Airlanding Brigade and the Airborne Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment in the evening of 6 June 1944. Likely, one of these Horsa gliders is the result of Southgate’s handiwork. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Shortly after the D-Day landings, Southgate’s 512 Squadron was in the thick of things as part of 46 Group, operating from an airfield known as B2-Bazenville. Here, Douglas Dakota Mark IIIs of No. 46 Group at B2-Bazenville, on the Normandy coast, are loading casualties for evacuation to the United Kingdom. Dakota KG432 ‘H’ of No. 512 Squadron RAF is at centre. When B2 first opened, the front line was only 9 kilometres away. The first aircraft to land at Bazenville were the Spitfires of 127 Group of the Royal Canadian Air Force on 11 June. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The greatest test of Southgate’s airmanship and indeed his luck was still to come. By now, he had survived almost five years of wartime flying operations and one near-death experience. Skill and professionalism had much to do with his survival to this point, but even Southgate will tell you... luck is a big part of it.

A little over three months later, Southgate’s 512 Squadron and its Dakotas participated in yet another airborne assault—this one the biggest of all. Operation MARKET GARDEN was the most ambitious aerial assault in history and one which failed to reach its goals. Its main objective was to punch into Germany over the Lower Rhine River in the Netherlands. The complexities of the operation and the tactics are far too complex to get into in this story, but it involved 41,628 airborne troops, one armoured division, two infantry divisions and one armoured brigade. In all, there were as many as 17,200 casualties with the loss of 144 transport aircraft. One of these aircraft was that of Squadron Leader Trevor Southgate

The view from a glider pilot’s perspective of a Dakota towing his glider towards the North Sea en route to Holland and Operation MARKET GARDEN. The coiled wire is a telephone line direct to the tow plane. Photo: GlideToGlory.com

A dramatic photo taken by a Dutch AP photographer shows streams of American Dakotas towing gliders overhead Valkenswaard near Eindhoven during Operation MARKET GARDEN. Photo: AP

DC-3 aircraft release their Horsa gliders over the Dutch countryside. Considering the altitude we see here, the gliders likely made just one turn into the wind before turning final and landing—a wise tactic to get the helpless gliders on the ground as fast as possible. The gliders at the bottom left are all grouped together at the end of a field, indicating they landed from right to left on that stretch of open farmland. Photo: RAF

As many as 100 Horsa, Hamilcar and WACO gliders crowd farm fields near Arnhem, Holland on the opening assault. It is astonishing that they all look relatively intact and that none appear to have collided with another. A few are burning—one furiously at upper left. Photo via ArmyPhotos.net

On 18 September 1944, the second day of the operation, Southgate departed RAF Broadwell and flew towards the Dutch town of Arnhem towing a Horsa glider. He was with his regular crew (Saunders, Co-pilot; Bryant, Navigator; and Parry, Wireless Operator) in Dakota KG570. The Horsa, hanging off the towline behind him, carried, in addition to its two pilots, a Jeep, a 6-Pounder artillery piece and the two British Army gunners who would man it. What happened next is explained by Flying Officer’s Parry’s note in the 512 Squadron ORB as well as personal accounts by Bryant and Southgate himself:

Accident report Dakota KG570 18/9/1944

On the 18th September 1944 whilst engaged upon a glider towing operation to an LZ near Arnhem we were attacked by an anti-aircraft battery at 14:21 hrs, 6 minutes before our ETA at the LZ. Upon hearing fire reports underneath the aircraft I reported to the Captain [Southgate - Ed] that the aircraft was on fire beneath the floor of the fuselage.

Acting upon his instructions I released the glider and attempted, assisted by F/Lt Saunders, to open the emergency escape hatch above the pilot’s head, but in vain.

The Captain then gave the instruction to bail out and I proceeded, accompanied by the navigator, to the rear of the fuselage and fixed my parachute.

The Captain of the aircraft then came to the rear and jettisoned the parachute door. It was then obvious to us that we were too low to abandon the machine. The aircraft was then burning fiercely but it was apparent that F/Lt Saunders still had control.

We braced ourselves at the rear and the aircraft was landed wheels up by F/Lt Saunders. Upon impact the machine swung violently to starboard and came to rest facing the way it had landed close to a wood. I then attempted to get to the front to assist F/Lt Saunders, but this was impossible due to the fire. I left the aircraft through the main door and proceeded to the starboard side at the front of the machine where I met the navigator and we attempted to assist F/Lt Saunders who was still in the cockpit.

We found this impossible and after about a minute as I was walking from the aircraft I turned and saw F/Lt Saunders accompanied by the navigator [Bryant - Ed]. He was badly burned around the head and arms and cut above the right eye, which was bleeding profusely. The Navigator, who spoke Dutch slightly, then contacted some farm labourers who advised us to hide in the wood. Having been in the wood about 10 minutes we heard footsteps, which turned out to be those of Dutch peasants.

By this point we were taken care of by the Dutch Underground movement and were eventually restored to the British Army safe and well. I feel that the safety of our crew was directly due to the outstanding performance of F/Lt Saunders in as much as his landing of the damaged machine was an epic of heroism which could hardly be surpassed. We were informed by the Dutch underground that our glider pilots and crew had made their way safely through the enemy lines taking with them 12 prisoners.

Signed J.H. Parry F/O, Wireless Operator in Dakota KG570

On the ground, crews struggle to wrestle a 6-pounder artillery piece (above) and a Jeep (below) onto an Airspeed Horsa glider. These are the two major pieces of cargo that Southgate’s tow (HG759) was carrying when he was forced to drop the line. Once landed on the ground, the rear section of the glider could be removed for quicker extraction of the equipment. Photos: Warr44.com (top) and ww2research.com (bottom)

Squadron Leader Southgate spoke of the incident on the website Pegasus Archive, a site dedicated to the Battle of Arnhem and Operation MARKET GARDEN: “When a few minutes from the LZ we were hit by flak which set fire to the aircraft below the flight deck floor. This spread rapidly and was soon near the overload tanks within the main cabin. The flight deck escape hatch was jammed, which meant leaving by the rear door after crash landing. Some of these tanks exploded on impact. We all had burns, F/Lt Saunders being the worst, F/O Parry had a broken ankle, and myself a fractured elbow.

We crawled into a small wood and eventually found by Dutch folks who had been in a church tower, and saw us crash. They took charge and moved us away to a house in a small village in the area. We stayed here for about a week looked after by Mr and Mrs Tuit; who took a great risk and were very brave. Everyone involved were in danger of capture and I cannot speak too highly of their efforts on our behalf.

We were finally rescued by an Army unit in a half-track vehicle at night, who moved us towards Nijmegen at high speed. Here we separated, F/Lt Saunders and I to the hospital, none of us ever met again. The war continued and we all went our separate ways.”

Southgate and Parry had gone to the back of the aircraft to release the parachute door when the realized that Saunders had stayed behind to attempt a wheels-up landing as the aircraft was far too low to jump. With flames threatening to explode the main fuselage tanks as well as blocking the route to Saunders in the cockpit, they braced themselves for the impact. The aircraft impacted the ground near the Dutch town of Dodewaard (possibly as far west as Tiel), on the banks of the Waal, a branch distributary of the Rhine. As reported by Parry, everyone was injured, especially Saunders. Both Saunders and Parry remained for burn treatment in the hospital in Holland. Southgate and Bryant were transported to Brussels and on to England. Trevor Southgate had a dislocated shoulder and a broken elbow. The Dutch people, who hid the crew for a week, told them that the Horsa glider (HG759) that had to be released prematurely had made a good landing, and in making their way to Allied lines, the crew and gunners had brought with them 12 German prisoners!

Dutch citizens examine the Horsa glider 759 where it came to rest at Indoornik. Moments later the tail was removed and the Jeep and 6-pounder artillery piece were rolled out. Both glider pilots and the two South Staffordshire Regiment gunners crossed the Rhine successfully by using the ferry/bridge at Driel, Holland and joined their own troops. Photo via Arie-Jan van Hees from Tugs and Glider to Arnhem – A Detailed Survey of The British Glider Towing Operations During Operation Market Garden, 17, 18, and 19 September, 1944

Here is Perry’s gripping account from Tugs and Glider to Arnhem – A Detailed Survey of The British Glider Towing Operations During Operation Market Garden, 17, 18, and 19 September, 1944, by Arie-Jan van Hees:

“We were detailed for a glider towing operation on the 19th of September 1944 to an LZ near Arnhem. We ran into light flak after crossing the Island of West Schouwen and saw the flak barge sunk by Typhoons. At 14:21 hours some five or six minutes from the landing zone at 2000 feet there were four or five loud bangs and immediately the wireless operator reported the aircraft on fire. The aileron controls were unserviceable and the glider release was pulled. Flight Lieutenant Saunders and Flying Officer Perry tried without success to jettison the pilot’s escape hatch, they then tried the axe but still without success.

I partly removed the fire extinguisher from behind the first pilot’s seat but the captain told me to leave it alone. We were now at 1000 feet and the captain ordered “Abandon Aircraft”. The wireless operator, myself and the captain went to the rear of the aircraft which was now well alight under the floor below the crew compartment door.

The captain was removing the parachute escape panel in the main door when I realized that Flight Lieutenant Saunders had not come back with us. By this time the aircraft was well alight at the main bulkhead and flames were licking around the fuselage tanks. It was now obvious that Flight Lieutenant Saunders was attempting to land the machine and it was far too low to bail out.

We braced ourselves for the impact and the aircraft belly landed and then swung violently to starboard and came to rest. Immediately on impact the fuselage tanks burst. Squadron Leader Southgate was flung across the fuselage. The captain, the wireless operator and myself left the aircraft through the main door.

The machine was now a blazing mess, upon going round to the front of the machine, Flight Lieutenant Saunders came round the starboard wing towards me, I then ran towards two farm labourers who approached the burning machine, and being able to speak Dutch asked them where the nearest Germans were. Upon being told we made for a nearby wood taking Flight Lieutenant Saunders, who was in very bad shape, with us. We hid until we were put in contact with ‘Dutch Underworld Movement’ and were looked after by them until Sunday morning 24th September 1944, when we contacted a British armoured car. Flight Lieutenant Saunders had been unable to leave the aircraft via the pilots escape hatch and it had been impossible to go back through the flames around the main bulkhead. He had broken the windshield and while he was struggling through, the front of the machine disintegrated and he fell to the ground. He sustained severe burns to his face and hands and a deep cut over his right eye and behind his right ear. Despite his injuries and loss of blood, when our first hiding place became dangerous he was willing to attempt a four mile journey on foot to a new one and had to be half carried over ploughed land at night.

Squadron Leader Southgate had his right elbow dislocated but an X-ray at the Casualty Clearing Station Nijmegen revealed that a small bone in his elbow was broken. Both he and Flight Lieutenant Saunders were detained in the hospital at Nijmegen.

We heard from the Dutch that our glider, No. 759, carrying two pilots, a jeep, a gun and two men made a perfect landing approximately one mile to the north of us. The jeep and gun got going heading north, a Dutch civilian brought them over the bridge to the LZ. Another report added that they arrived with twelve prisoners.

I would like to say that the crew owe their lives to the second pilot, Flight Lieutenant Saunders, for his outstanding effort in landing the flaming and crippled aircraft.”

Saunders, for his bravery and devotion to duty, was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. His citation appeared in an edition of the London Gazette, 2 February 1945. It read: “This officer has participated in numerous sorties and has set a fine example of skill and resolution. In September 1944, he was a pilot in an aircraft which towed a glider during the airborne operations against Arnhem. When nearing the landing zone, the aircraft was badly hit and caught fire. The situation was extremely serious but, with the utmost coolness and—with complete disregard for his welfare, Flight Lieutenant Saunders executed a successful crash landing. He was trapped in the cockpit but was thrown clear when the aircraft exploded. He sustained serious injuries and was badly burned. In the face of extreme danger this officer displayed courage and devotion to duty of a high order”.

Southgate survived this second brush with death, one that put him in the hospital in England before he returned to his 512 Squadron. He continued to serve with 512 for another year, when he was demobilized on 1 June 1946. His career had been both humble and heroic, both steady and stellar—a portrait of devotion to duty and teamwork. He had flown continuously for 8 years—since his first solo in 1938, save for his two periods of recuperation from wounds. He had flown in some of the most dangerous skies in Europe—from Reims to Malta to Normandy and on to Arnhem Land. He met and flew the Allied leaders tasked with the execution of a war he knew was coming when he was a boy. He amassed over 2,200 hours of difficult flying and mastered the controls of everything from a Hawker Hart to a Spitfire to a Fokker XXII to a DC-3. It was time to go home.

512 Squadron Dakota Mk III, HC-AT (RAF Serial No. KG330), lands at the Brussels Airport to repatriate Belgian nationals from Germany—both slave labourers and former concentration camp inmates. This 512 Squadron aircraft brought in the infantry and airborne commandos that fought to free them and then brought them back home—an honourable history if there ever was one. And in an unlikely coincidence, KG330 is still flying today from Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canadian registered as C-GWXZS and a television star flying for the cameras for the hit reality series Ice Pilots NWT. KG330 also flew paratroopers on D-Day, but Southgate’s logbook indicated that he did not fly KG330, but he flew the next in line, KG331. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Far, far away and seventy years after rescuing Belgians from Nazi concentration and forced labour camps, RAF Dakota KG330 thunders down an ice runway in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories on Great Slave Lake. Photo: Jason Pine Photography

After a well-earned rest, Squadron Leader (Ret’d) George Trevor Southgate went to work for a company called Metal Box and Printing Industries, a company that made most of the metal boxes, cans and containers in England. Like so many of the heroes of the Second World War, Southgate melted back into the fabric of society, building the better future they had all fought so hard for. Southgate and his wife Mary (Turner) retired to Worcester, England but, in 2008, decided to emigrate to Canada to be near their daughter and grandchildren. They were both 88 years old at the time. Mary passed away in 2012. He lives today in a retirement residence in Ottawa. He will be 95 in just three months.

Dave O’Malley

The author would like to thank Neil Richardson (Southgate’s grandson) for his assistance in this project, as well as Richard Lacroix, Rob Kostecka and the Imperial War Museum