CLUB RUN TO MALTA

The "Club Run" was an informal name for aircraft supply operations to the besieged island of Malta during the Second World War. During the interminable ordeal that was the siege, the Royal Navy and the merchant navy put together almost non-stop convoys to resupply the island with food, materiel and weapons. This included most importantly the supply by aircraft carrier of combat aircraft such as Albacores, Fulmars, Swordfishes, Hurricanes and Spitfires. These aircraft were flown off when they were in range, escorted by experienced Malta hands. Starting with Operation Hurry in August of 1940, the Royal Navy (including USS Wasp) made 28 “Club Runs”, ending with Operation Train in October of 1942, attempting to deliver more than 750 aircraft, Not all aircraft were launched or made it to Malta if they were, but enough were delivered to make the difference in the Malta air war. Here is the story of on such “Club Run”, Operation Salient, told through the eyes of Flight Sergeant Calvin Taylor, a Canadian who was one of the 32 Spitfire pilots on HMS Eagle who made it to Malta on June 9th, 1942.

Leaning against the merchantman’s railing near the aft 4-inch gun emplacement, 23 year-old Sergeant Pilot Calvin Taylor and his travel mate were taking in the late spring ocean air and enjoying the sea voyage to Gibraltar. Having embarked at the rainy Milford Haven docks in Wales aboard the MV Hopetarn, they departed on May 26, 1942, without being told their final destination. Cal undoubtedly wondered if his request for an “Eastern” posting, which could be anywhere from the Mediterranean to Ceylon in the Indian Ocean, was the smartest thing to have done. Remaining preoccupied, he watched as the British Isles slowly disappeared over the horizon beyond the trailing seagulls.

Equally on his mind were his folks and friends that he last saw back home in northern Ontario. A fleeting thought of his first flight in a Norseman seaplane at Sioux Lookout during spring 1937 drifted through his mind. He was just out of high school then, heading by bush plane to work at a remote gold mine when he got that first taste of flying. Now, less than five years later, he was piloting the finest combat aircraft in the world and heading to exotic lands. Some of his friends had also signed up, and he had heard that Johnnie Wilcox, also of Cobalt, had been posted to Egypt with the RAF. Lighting up a Player’s Navy Cut cigarette, he reflected that it would sure be nice to join him there. Still, anything was better than the lack of activity in Northern Ireland.

After basic flight training was completed in Canada at Cap-de-la-Madeleine and Borden with the RCAF, Taylor flew another 53 hours at 53 OTU at Gloucestershire, England and 47 hours at 152 Hyderabad Squadron at Eglington, Northern Ireland. By now Cal had 77 hours on Spitfires and had become rather proficient on the type, but had accumulated less than two hours on actual combat operations. That one combat mission came from a scramble to intercept what turned out to be a friendly aircraft.

LAC Cal Taylor (Left) sits at the controls of a Fleet Finch during his training at No. 11 Elementary Flying Training School. Right: Flight Sergeant Cal Taylor, a Malta veteran, in full desert rig in Egypt in 1943. Photos via Cal Taylor

Young Flight sergeant Cal Taylor (right) leans casually against a Spitfire of 152 (Hyderabad) Squadron, Royal Air Force in Londonderry, Northern Ireland prior to his deployment aboard MV Hopetarn and HMS Eagle.

He wanted to improve on that, while seeing more of the world in the process. His unit, 152 Hyderabad Squadron (RAF) was slowly being re-equipped with the faster Mk Vs but was not being moved from the relative safety of Ireland anytime soon. His new posting was immediate and as a result, he was sent to RAF West Kirby near Liverpool to be issued with warm weather clothing including khaki shirts, shorts and pith helmet or “topee”. With that came a new parachute with an attached emergency dinghy and Mae West life vest and lined flying boots.

Aboard the recently built, 5200 ton British steamer Hopetarn, everything seemed in control. With a new companion who he had just met in West Kirby, and both being sergeants, they were allotted their sleeping quarters with the other NCOs and airmen on this passage. During the day, the hammocks were taken down as the quarters doubled as their eating mess.

As they chatted, Taylor soon learned that his new companion was from Cartierville, Québec and his name was George Beurling. Even with both being Canadian, they were posted to the RAF, although different paths had brought them together. Beurling already had his commercial pilot’s licence, with experience on bush planes in Québec before signing up with the RAF in the UK. He was earlier turned down by the RCAF for not meeting their educational requirements.

The 13 commissioned officers aboard were billeted in staterooms and the sailing was most pleasant during the first portion, until the convoy hit rough seas in the Bay of Biscay where most passengers became seasick. Cal still remembers the horrid smell emanating from the NCOs’ mess as most simply got sick over the side of their hammocks with the remains of the previous dinners and drink rolling back and forth on the mess floor.

Not surprisingly, Beurling and Taylor spent most of their time up on deck.

The weather finally cleared as the ships continued southwards towards warmer climates. Undoubtedly, they were again enjoying the ocean scenery and feeling somewhat safe with two escort ships, the frigate HMS Rother and the corvette HMS Armeria, cruising nearby, searching for the ever-present threat of German U-Boats.

Though there are no known photos on the internet of the cargo vessel MV Hopetarn, we can show you two of her escort vessels on her important trip to Gibraltar. HMS Armeria (K187) was a Flower Class corvette of the Royal Navy, originally built for the French Navy. Armeria would eventually be stripped of her military equipment and be rebuilt as a merchantman, first called Deppie, then Canestel, then Rio Blanco, and finally Lillian. RN Photo.

HMS Rother was a River Class frigate of the Second World War, launched only months before this particular escort duty. . All River Class ships of this design wer named after rivers in the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth. River Rother is a river in the northern midlands of England, after which the town of Rotherham and the Rother Valley parliamentary constituency are named. These frigates were specifically designed as anti-submarine escorts for trans-Atlantic convoys. River class frigates offered the size, speed, and endurance of escort sloops using the inexpensive reciprocating machinery of corvettes. River class were designed for North Atlantic weather conditions and included the most effective anti-submarine sensors and weapons. RN Photo

Related Stories

Click on image

The steamer, with the RAF personnel and their special cargo aboard, arrived safely at the British colony of Gibraltar off of Spain’s southern tip on June 2, 1942. The imposing “Rock of Gibraltar”, is also the gateway of the Mediterranean Sea; and was possibly Cal Taylor’s new area of operations.

The hot weather was most welcomed and the airmen were given billets ashore in metal Nissen huts fitted with bed cots. Leaving their kit behind, Cal and George together headed anxiously to the assembly hall to hear from their new Wing Commander.

The talk was short where their commander announced what some already suspected, that they were now headed to Malta, 1100 miles away. To get there, the Hopetarn was also carrying 32 new, tropicalized Spitfire VCs, which were now being brought ashore to North Front airfield to be reassembled. Before heading further east, 90-gallon overload fuel tanks would be fitted giving them a total of 157 gallons in each Spitfire. This would allow for four hours from launch point aboard the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle, to fly 700 miles to the besieged island of Malta.

They were invited to visit the town, but to be back by 1700 hours. The Wingco added, “Keep closed mouths, as the place is full of spies who already know a lot and we don’t want to help them.” With that he added, “The Germans and Italians will already know you are coming as soon as their spies see the Eagle and its escort leaving port.”

The wing commander went on to say, “Of the last lot that flew there, four aircraft were shot down on approach to Malta.” [This was Operation Style, about which an article has already appeared in Vintage News. One of the four unfortunate Spitfires that the Wing Commander was mentioning was flown by Ottawa native David Rouleau.- Ed. Click here to read the story]

The men already knew that this beleaguered island, located between Axis-held territory in North Africa and Sicily, was known by this time as the “Most bombed place on earth” as the fascists tried with everything they had to eliminate the island defenses. It was imperative for the enemy to protect their convoy routes supplying General Rommel’s Afrika Korps.

The assembly was concluded with the stern advice that those pilots who have a change of heart or otherwise were not up to such a dangerous and daring naval operation, could privately meet with the Wingco and withdraw from the mission without penalty. In the same breath, he announced that there were four pilots in the group that did not have enough operational flying hours for such a mission and would be returned to England on the next available ship. He named the four and Sgt. Cal Taylor was one of them. So that was that, Cal thought.

On the next day, both George and Cal walked from the navy base to visit a friend by the name of Roy Allen of Cobalt, now posted to Gibraltar with the Canadian Tunnelling Corps. He was a hard rock miner from the gold and silver mines of northern Ontario, engaged at drilling and blasting out caverns in the Rock for a hospital.

They got a tour of the operation including walking to an opening high up on the mountain where they could see Morocco across the straits.

Cobalt Ontario is a hard rock mining town in Northern Ontario. The town produced many highly experienced miners , some of whom were assigned to No. 2 Tunnelling Company Royal Canadian Engineers, which embarked in March of 1942 for Gibraltar, where it was to reinforce other Canadian tunnellers who had been working on and in the Rock since the previous autumn. These Cobalt boys were those who hosted Taylor and Beurling for a tour of the tunnel work.

Resolved to the fact that he was returning to England, Taylor joined Allen and other miners he knew there for supper while George returned to camp. After dinner, Cal and his friends visited a cantina, where they had the local wine.

The wine almost immediately did not agree and soon Taylor found himself violently ill. During their earlier wing assembly, the airmen were warned not to try the “Stuka Juice”, but he did not know the wine was the same until it was too late. George was very supportive of his companion on his return by vehicle to the base. He ended up ill in bed and Beurling thoughtfully brought what he hoped Cal could eat, and keep down.

Keeping his condition secret for fear of being grounded, the next day Cal attended the scheduled meeting and was told that he would be going on the Eagle, but only as a spare pilot. Moreover, just prior to the sailing of the convoy, Taylor was delighted to be told that he was going to be flying the mission after all.

HMS Eagle, by the time of the Malta Club Runs was an obsolete carrier. Eagle spent the first nine months of the Second World War in the Indian Ocean searching for German commerce raiders. During the early part of the war, the Fleet Air Arm was desperately short of fighters and Eagle was equipped solely with Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers until late 1940. She was transferred to the Mediterranean in May 1940, where she escorted multiple convoys to Malta and Greece and attacked Italian shipping, naval units and bases in the Eastern Mediterranean. The ship also participated in the Battle of Calabria in July, but her aircraft failed to score any hits when they attempted to torpedo Italian cruisers during the battle. Whenever Eagle was not at sea, her aircraft were disembarked and used ashore.

The ship was relieved by a more modern carrier in March 1941 and ordered to hunt for Axis shipping in the Indian Ocean and the South Atlantic. Her aircraft sank one German blockade runner and disabled a German oil tanker in mid-1941, but did not find any other Axis ships before the ship was ordered home for a refit in October. After completing a major refit in early 1942, the ship made multiple Club Runs, delivering fighter aircraft to Malta to boost its air defences in the first half of 1942. Eagle was torpedoed and sunk by the German submarine U-73 on 11 August 1942 while escorting a convoy to Malta during Operation Pedestal.

A nice shot of HMS Eagle slowly making its way out of Grand Harour, Valetta, Malta during a more peaceful period.

With Operation Salient underway, such aircraft ferry operations to the besieged island of Malta were covered by Force H based at Gibraltar and made up of the Royal Navy’s most efficient warships. Such a requirement was necessary given the well-trained Axis forces operating in the Mediterranean.

So, late on June 7, 1942, they boarded HMS Eagle, along with the 32 assembled Spitfires, which had been ground tested and engines checked again on the ship’s flight deck.

Still feeling the effects of the spiked wine, Calvin, with George, found a spot to sleep under the wing of one of the Spitfires. They thought it best to sleep on deck for their short time on the carrier, which was most likely being stalked by enemy forces, a wise thought too, as the Eagle was subsequently torpedoed and sunk by the Germans just four weeks later.

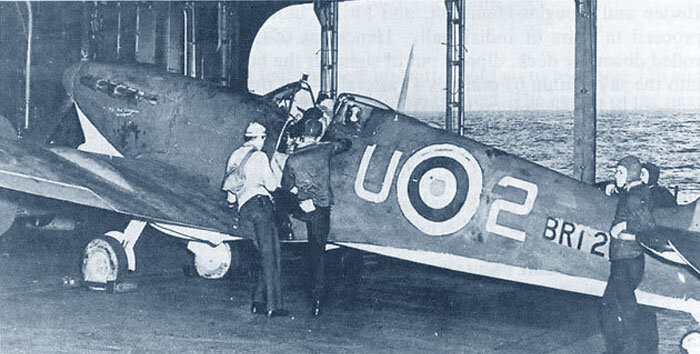

Before sun up, they were under way with a sizeable escort of two Royal Navy cruisers, the HMS Cairo and Charybdis, as well as six destroyers. At first light, the pilots searched for their assigned aircraft. Taylor’s Mark VC machine had tail number BR 463. Following more briefings and preparations, Cal had managed some sleep before the crews were mustered hours before sunrise on June 9.

After something to eat in the ship’s mess followed by a traditional tot of navy rum, they were prepared and ready for launching. The Eagle was a relatively smaller fleet carrier, built originally from a cruiser hull; its flight deck was only 660 feet long.

HMS Cairo, a C-class light cruiser, was one of the key escort ships during Cal Taylor's Operation Salient. Two months later, Cairo took part in the now-famous Operation Pedestal, the escorting of a convoy to Malta. During the operation she was sunk by the Italian submarine Axum north of Bizerta, Tunisia on 12 August 1942.

Royal Navy Dido Class cruiser HMS Charybdis was part of the Gibraltar-based flotilla that escorted Club Run carriers in their missions to bring aircraft to Malta. Charybdis had a critical part in 22 Malta resupply missions. Following her Malta work, Charybdis was sunk with the loss of 30 officers and 432 ratings in the Bay of Biscay, the victim of German torpedo boats. RN Photo

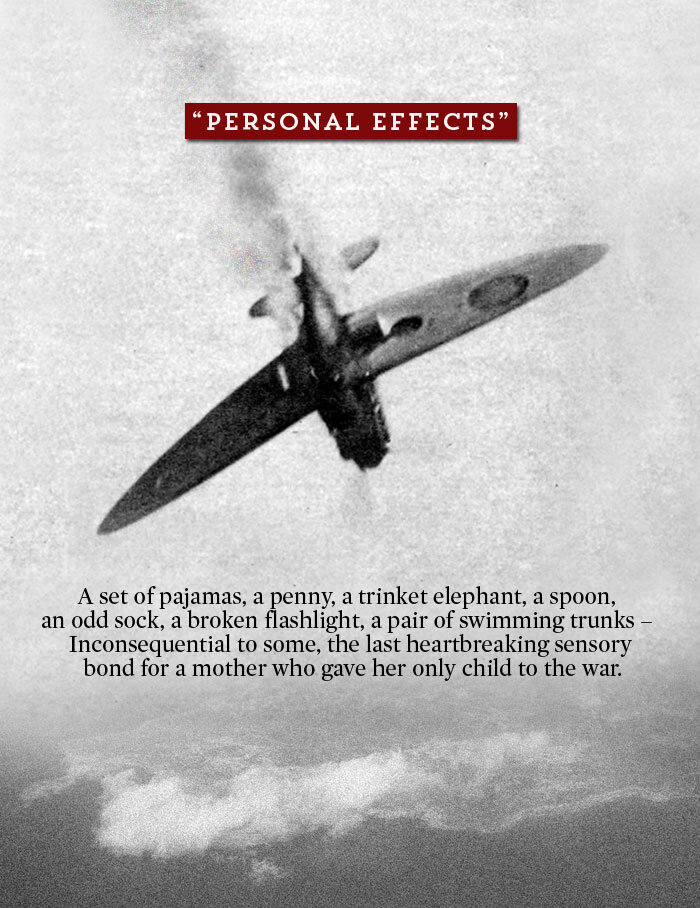

A couple of months later during Operation Pedestal, Eagle was torpedoed and sank... proving the danger for sailors as well as airmen.

Because the Spitfire only had full landing position flaps, or none at all, a temporary solution to add 20 degrees of flap angle was employed for the carrier takeoff, made usually with gusty 35 mph headwinds. This adjustment was carried out by lowering the flaps, inserting wooden wedges, then partially closing the flaps against the pieces of wood, lodging them against the wing.

Taylor was to be second off the carrier, behind veteran Malta pilot, F/Lt Tilley, who was to lead them to the island’s airfields. They were 400 miles into their sea voyage and now sailing off the Algerian coastline while the pilots got the order to start engines after making last minute cockpit checks. With the carrier turning into the wind with a marked increase in speed and funnel smoke, they were reminded again over the roar of dozens of Merlin engines to make certain that the props were set for fine pitch, as their lives depended on it.

On a previous mission to Malta, flying from the larger USS Wasp, an old buddy of Cal’s from training in Canada—Don Sherrington—lost his life when he took off with his variable propeller set on course pitch and immediately crashed underneath the carrier’s bow from lack of sufficient thrust.

USS Wasp (CV-7) launches a Royal Air Force Spitfire VC during Operation Bowery, May 1942. In this trip, one Spitfire landed back on Wasp despite not having arresting gear. We can just make out the 60 gallon “slipper” tank slung beneath the fuselage.

Operation Bowery included tropicalized Spitfires from HMS Eagle (background) and USS Wasp (Foreground). On May 9th, 1942 Wasp flew off 47 Spitfires and Eagle 17, three crashed during the passage (one in the sea on take off, one crash landed back onto Wasp and one off Malta, a fourth lost its way and arrived in North Africa) but 60 Spitfires were in action within thirty five minutes of landing.

A fabulous photograph pf a Spitfire “Trop” riding the elevator to the flight deck of USS Wasp during a Club Run. When Wasp delivered 47 Spitfires to Malta in Operation Bowery, they were assembled out of the box on the hangar decks of the carrier. Here we can easily tell that this Tropical-ized Spit is perfectly brand new, not a mark or stain on her. We clearly see the air intake for the large “Vokes” sand filter, as well as the large “slipper” gas tank mounted beneath the wing centre section. Small hooks were fitted, just forward of the inboard flaps: when the tank was released in flight these hooks caught the trailing edge of the tank, swinging it clear of the fuselage. On deck we can see another Spit as well as an American aircraft - possibly an Avenger

Down on Wasp's hangar deck, a Spitfire “Trop” is checked out before going topside.

With the brakes on, the pilots were carefully checking their pitch, mixture, engine gauges, and flying controls against a strong headwind that was enhanced by the ship’s speed which was now beyond 20 knots. Watching the paddle man’s signals as the chocks were pulled away from the lead aircraft, Tilley’s craft began accelerating into the wind immediately, and then appeared to slowly lift off into the sky only to momentarily disappear below the bow, before starting his climb. Many of the ship’s crew were intently watching the action from the railings of the island superstructure.

Enhanced by the flying sea spray, the 22,000-ton aircraft carrier reached another trough, the point where Cal got his take-off signal. Instinctively, he added full throttle as the crew pulled the chocks out and he released the brakes. Watching for the deck hands, he kept one eye on the starboard wing as it cleared the ship’s island by a couple of feet. As instructed, he then lined up the port cannon to the deck’s centre line as his machine rapidly accelerated. With the carrier now cresting the wave, Cal recalls that he staggered the heavily laden aircraft into the air. Drifting closer to the port side of the ship, he worked to compensate for the sluggish controls, strong gusts, and the torque of the Merlin engine’s 1440 horsepower. Clearing the flight deck, his brand new Spitfire progressively gained speed and stability. He lowered the flaps to drop the wedges, then slowly closed them and raised the gear at the same time mentally calculating for his rendezvous with Tilley’s climbing Spitfire. Three different flights totalling 32 aircraft, formed up separately. The first group that Taylor was part of headed to the Maltese airfield known as Luca with the other two flying to Takali and Halfar.

Young RAF Spitfire pilots walk the deck of HMS Eagle after receiving their final instructions before flying a successful reinforcement of nine Supermarine Spitfires to Ta Kali, Malta. This photo was taken en route to Malta during Operation Picket I, another Club Run which was carried out in March of 1942, three months before Taylor's voyage. Note the Spitfires in the background.

A tropical-ized Spitfire Mk VC thunders down the flight deck of HMS Eagle during Operation Picket I, an earlier Club Run. Note the many sailors watching from the edge of the deck.

A shot from an early Club Run known as Operation Picket I which was carried out three months prior to Operation Salient. Supermarine Spitfire Mark VB(T), BP844, the first of a further nine Spitfires to reinforce the RAF on Malta, taking off from the flight deck of HMS Eagle with Squadron Leader E J "Jumbo" Gracie at the controls. Behind him, the other aircraft await their turn. These Spitfires, equipped with 90-gallon ferry drop tanks, flew to Ta Kali to re-equip No. 126 Squadron RAF, which Gracie was to command. BP844 was shot down over Malta, with the loss of its pilot, on 2 April 1942.

Levelling off at about 12,000 feet, perhaps a collective sigh of relief from the pilots was had, given that they successfully completed their first and probably only carrier takeoff.

Heading towards the rising sun and Tunisia, they cut across Cape Bon and the city of Tunis. About two hours into their mission, when their engines began to cut out from fuel starvation, they switched to the main tank and jettisoned the empty “slipper” reservoir with 87 gallons remaining now in the three internal tanks.

All eyes kept a close watch for the enemy in the worsening visibility as they were now near the Italian island of Pantelleria. It had become very hazy and they were out of sight of land once again. Soon, it was noted that they were slightly off course as the enemy island of Lampesdusa appeared off to starboard. Making matters worse, the pilots were warned by radio from the Malta controller that the enemy was in the air above Malta, probably looking for them, as Cal had figured, and to keep a sharp lookout–something Taylor thought without a doubt was already being done.

By now their fuel was so low that Cal’s gauge was barely showing any content, and they were still over water. Feeling the pressure of possibly having to ditch at sea, Taylor was relieved to suddenly see land once again. Continuously expecting enemy aircraft, they were afforded some protection from the continuing haze.

Flying tight circuits in preparation to land at Luca, they lowered the flaps and gear while scanning the skies above them. One of the Spitfires had its engine quit after touchdown–out of fuel. All of the aircraft had arrived safely, dispersed at three different airfields, with Beurling’s flight landing at Takali. They were fortunate for the poor visibility, or it could have been far worse.

In the midst of blinding dust, the Spitfires were promptly guided into sandbagged bays and the pilots were signaled to shut down. They were then quickly pulled from the cockpits by the ground crews, while the aircraft were refueled and rearmed within minutes. Before Cal could collect all his personal gear that was thrown in the dirt by an armourer from being stowed in the gun bays, another pilot had started it up and took off to engage the enemy.

Sergeant Taylor and another pilot, who flew the mission as spares, were invited by their CO to stay and fight on, given they had just gained enough “operational experience” flying to Malta.

After a few days of action, Taylor’s Spitfire was subsequently brought down after a Macchi 202 of the Aeronautica Militare Italiana inflicted considerable damage on his aircraft. Managing to save what remained of his machine, Sgt. Taylor discovered after his forced landing at the airfield, that he had been injured in the leg by splinters from a cannon projectile that had exploded behind his armoured seat. After medical treatment, he was removed from flying for a few days.

Always well outnumbered, the new pilots soon discovered that the situation on the island was so desperate that on average, of every flight that took off after the enemy, perhaps half returned—and usually to a bombed-out field. During the early spring 1942, only eight serviceable Hurricanes remained. But by the end of July, thanks to Taylor’s mission and other ferry runs, the RAF now had 80 serviceable fighters in Malta, mostly the latest Spitfire VCs, with an average of perhaps 15 a week being shot down or too badly damaged to fly again. Aircraft maintenance was no doubt a nightmare on the island where nothing went to waste. Any foodstuff was at a premium and everyone on the island, including the pilots, suffered from malnutrition, with some even contracting dysentery.

Squadron Spitfire Mk Vc “Trops” overflies Malta. Though dark in this photo, these Trops would have been painted in typical desert camouflage. These Spits are with 249 Squadron - Beurling's unit.

While in Malta, George Beurling also survived combat damage to his aircraft, including being shot down and injured in the foot. He did, however, shoot down an incredible 27 confirmed enemy aircraft in just a couple weeks over Malta with most being the latest German and Italian fighter types. Earning the monikers of The Falcon of Malta and Screwball, he eventually became the top scoring Canadian ace of the war with 33 1/3 confirmed “kills.”

Before the siege of Malta was over, Rommel’s troops had encircled the Libyan city of Tobruk, forcing the British and Australian armies to withdraw towards Cairo. Within two weeks of arriving on Malta, Taylor and his 601 Squadron mates were removed from the operational roster on June 26 in preparation for their transfer to North Africa in support of the British Eighth Army. As he had hoped earlier, Taylor was finally going to make it to Egypt, where his adventure would continue.

After his stint on Malta, Taylor (left) flew Spitfires with 601 City of London Squadron (Auxiliary Air Force) in North Africa.

After the war, Cal Taylor (second from right) flew Mustangs with the RCAF as part of 403 “City of Calgary” Squadron - an auxiliary/reserve squadron. This photo was taken at RCAF Station Rockcliffe on their arrival from Calgary. Cal also flew Vintage Wings' own Mustang more than a dozen times while with 403.