HERO — A Flying Tribute to a Missing Aviator

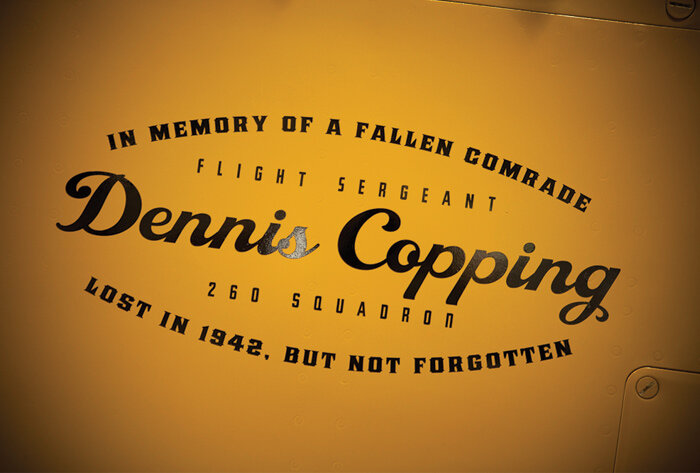

Vintage Wings of Canada's core program called In His Name dedicates each of the eighteen aircraft of the collection to a Canadian veteran, famous or otherwise, native or foreign born, who had an association with the aircraft type during their flying career. All aircraft carry a dedication panel on each side of her fuselage. Only one aircraft, the Stocky Edwards P-40 Kittyhawk, will now carry two dedication panels. The first is to Wing Commander James Francis “Stocky” Edwards, of Nakomis, Saskatchewan, the great Kittyhawk legend and Canada's highest scoring living ace. The other is for one of only two non-Canadian honourees of the In His Name program – Flight Sergeant Dennis Copping of Southend, England (the other is China-born American John Gillespie Magee who in fact flew for the RCAF). Copping, the son of an English dentist, and Edwards, the Saskatchewan farm boy, knew each other, as they both flew with 260 Squadron in the desert campaign of North Africa. They both flew Kittyhawk HS-B (Serial Number ET574). Edwards survived the war and lives today in Comox, BC. Dennis Copping did not survive. He would be lost in Kittyhawk HS-B, while Stocky went on to fame in its replacement - a new Kittyhawk HS–B, serial Number FR350.

Seventy years later, the world would finally learn that the first Kittyhawk did in fact survive the war, not entirely intact, but just the way Dennis Copping last saw it. We are proud and honored to co-dedicate the Vintage Wings P-40, which is painted as 260 Squadron's HS-B (FR350), to Stocky's lost squadron mate, Flight Sergeant Dennis Copping.

Al Wadi al Jadidi is a vast, trackless, forbidding and inhospitable skillet of heat shattered rock, washed and scoured by an ocean of acid yellow sand and gaseous shimmering horizons. Spend a few minutes on Google Earth to scroll across its interminable and tempered face and you will understand that this Montana-sized torment holds the very minimum of life as we know it. It has more geologically in common with Mars than Earth. From above, there exists only an endless sea of shifting grit and sand with rocky and toxic-looking ulcerations erupting from its salty skin. There are no roads, no trails, no communities, no possibilities for sustaining human life without water and food. It is utterly heartless. Just sand and rock scrabble and heat and time. Today there is nothing “out there” to keep a man alive–seventy years ago there was even less. It was the last place on earth that Flight Sergeant Dennis Copping wanted to get lost in while his P-40's Allison engine drank the life-giving fuel from his tanks.

In June of 1942, seventy years ago almost to the day, Copping, a Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawk pilot with 260 Squadron RAF, found himself with no other option than to make a forced landing under power, far out into this sea of suffering. Having lost his way during a ferry flight from his unit's forward operating base close to the fighting around Cairo in northern Egypt to a repair depot, it seems he decided to fly the aircraft to a landing while he still had enough gas to change his mind about his landing spot.

Just the evening before, he was returning late from a mission and landed into the glare of a setting sun near Cairo. Unable to gauge his height due to dust and the low sun in his eyes, his landing was particularly hard and the P-40's landing gear suffered damage. The next day he was ordered to fly the P-40, marked HS-B, to the repair depot… with the gear locked down. He was loaded with ammo for his guns, though with gear locked down, he would have been at an extreme performance disadvantage if he had run into an enemy. At the best of times, the Kittyhawk, a formidable ground attack platform, was outclassed by the more powerful German Bf.109

No pilot would have chosen to land with his wheels down in such a place–with nothing to set his tires on other than soft sand and ancient broken rock, yet it is clear he did. He had no choice. When his landing gear hit the desert floor, they sheared off, with the port one possibly punching a sizable hole up through the port tail plane. The Kittyhawk clapped onto its belly, sliding many meters on the sand and rock, shedding the aircraft's chin intake, cowling and the radiator set it contained. The propeller beat against the ground, with the metal blades twisting and curling like fiddleheads. As Copping ground and shrieked to a stop, the propeller and reduction gear broke away, spinning off to starboard.

Copping's wrecked P-40 still sits in the Egyptian desert. Other than the 70 years of scouring by the sand and the recent ravages of vandals, it is exactly as Copping would have seen it when he turned one last time to look back at the aircraft he was supposed to deliver to the repair depot. Copping walked into oblivion, where he remains today, though, with the appearance of his Kittyhawk, we now know what happened to him. Photo Jakub Perka

The dry desert air has preserved all the metal parts of Copping's Kittyhawk, but all the fabric which covered the tail feathers has now disappeared–dried, cracked and blown away by seventy years of hot desert winds and freezing nights. The water soluble paint which was used to write the HS-B designators on the sides was also mostly carried away on the scouring winds. Photo Jakub Perka

Related Stories

Click on image

Every time I look upon the now famous images of amateur photographer Jakub Perka, I do not see a remarkably intact P-40 like everyone else. I don't see a potentially valuable warbird for restoration or display in a museum. I hardly see the airplane at all. What is see is the ghost of Dennis Copping, its unfortunate and brave young pilot.

I can just imagine his mounting stress and fear as his fuel gauges dropped inexorably towards empty, while he circled trying to find a fix on something, or while he droned steadily along a course he could not know was taking him farther into trouble. I feel his momentary elation as he gets the Kittyhawk back on the ground without killing himself. I see the smoking ruin of his beautiful fighter. I hear the ticking of its cooling engine, the dripping of glycol, feel the invasion of blast furnace heat as he slides back the canopy and steps out onto the wing. I smell the hot oil now bleeding from its once mighty Allison heart, staining the desert floor. I see him standing there, beside his aircraft, perhaps dazed, when his forehead hit his instrument panel, and not yet fully understanding the trouble he now faced. I see him unhook his parachute and toss it onto the sand behind the port wing. Was he happy to be down or was he panicked after destroying his Kittyhawk charge?

A gunslinger shot of Copping in a desert P-40.

I see him in my imagination walking around the wrecked fighter, assessing the damage, perhaps touching the twisted mess that was his propeller, wondering what to do, talking to himself. The elation of living through the crash must have quickly given way to increasing terror. He was alone, and it had been an hour of flying since he last saw signs of human activity slide past his wing. It was hot, terribly hot – June in the Sahara desert on the Tropic of Cancer hot. My guess is he walked to the higher ground nearby to scan the emptiness. The realization and the terror of his situation must have started settling in. A man could not be more alone than this and still be on the planet Earth.

In one of Perka's photos, I see the D-ring of his parachute release on the port side, half buried in sand, and I know that his worried hand was the last to touch it as he deployed his chute to make a shelter from the searing, brutal sun. I see that the battery and a broken radio were removed from the fuselage compartment behind the cockpit, and I know he was fiddling with them to get the radio to work. There is evidence of possible ground fire damage on the top side of the rear fuselage. If this is ground fire, there is a good chance that this hit also damaged the radio which is secured in the compartment directly beneath the exit holes. Pilots who took off with Copping indicate they were shot at and that they were unable to raise Copping, who was clearly heading in the wrong direction.

I see the remnants of his white parachute in the lee and shade of the broken Allison, and I know that he sat beneath it, perhaps for a long time trying to decide what to do. It is clear that at one point, suffering from terrible thirst and despairing of his squadron ever finding him, he made the decision to walk out, hoping that, of the 360 course choices he could make, he had somehow chosen the right one that would bring him to water or even salvation. What he also probably knew, even then, was that no matter what he did, he had no chance of survival.

If I could speak to Dennis Copping, I would tell him:

“Rest now Sergeant, we have found you. It took seventy years, but now the world knows. Now your family knows. Vintage Wings of Canada will carry your name on our Kittyhawk HS-B and we will tell Canadians and the world of the great courage it took to be a fighter pilot in the desert and take a fighter across hundreds of miles of forbidding danger to a repair depot. We will tell them of your ordeal and suffering. We will tell your story Sergeant. Rest now”

Dave O'Malley

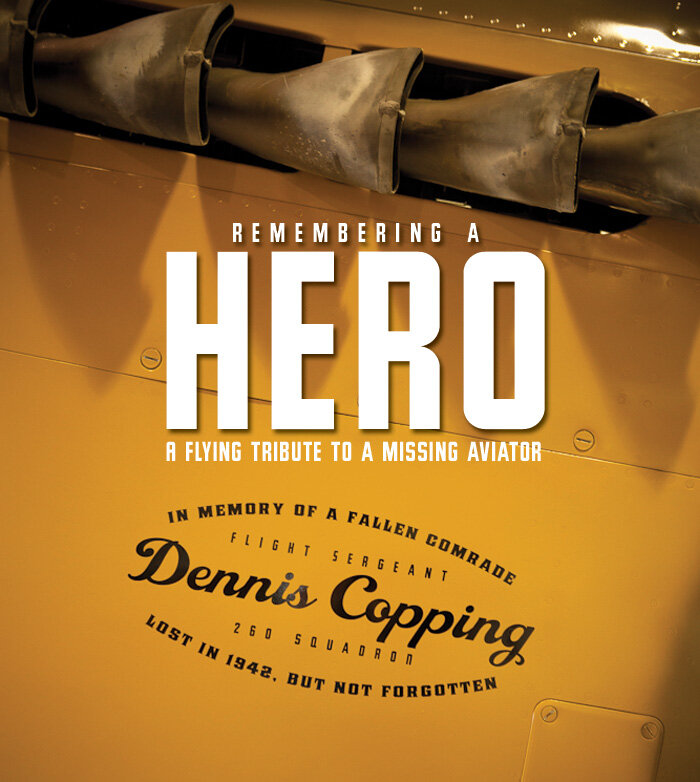

The cowling of Vintage Wings of Canada's Stocky Edwards Kittyhawk will wear a dedication to Dennis Copping for the 2012 flying season when we celebrate the Warbirds of the Med, the fighters of Malta and North Africa. Here we see the Warbird of the Med badge and the Copping memorial. Photo: John Kealey

A close up of the Copping dedication panel which is carried on both sides of the cowling. Photo: John Kealey

The 269 Squadron Kittyhawk HS-B carries Dennis Copping's name on both sides of her fuselage. Photo: Peter Handley

Kittyhawk pilot and aircraft manager, Dave Hadfield took two photos of Dennis Copping along with him on his recent journey to south eastern Onatrio's Camp Borden air show. Not only did he tell the story of Copping's service and mystery solved, he took photos of these people with Copping, keeping his memory alive. Photo: Dave Hadfield

Here, stopping in at Lake Simcoe Regional Airport for fuel, Operations Manager Chris Drumm and friend Christina and her daughters share the story and the images of the lost aviator. Photo: Dave Hadfield

At the Borden Show, Captain Indira Thackorie of the Canadian Forces Skyhawks parachute demo team learns about Copping and his story... yes Dennis, the world has changed quite a bit! Women in the army parachute teams! Photo: Dave Hadfield

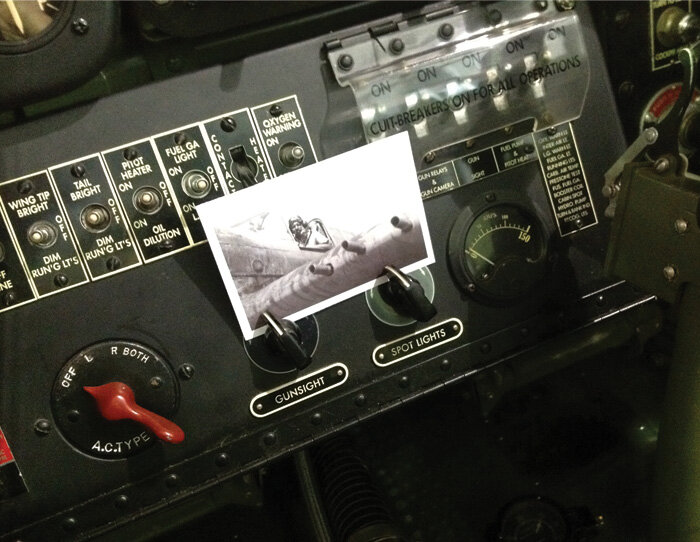

Copping’s photos in the Vintage Wings Kittyhawk

A shot of the cockpit of Dennis Copping's 260 Squadron Kittyhawk HS-B, now, 70 years after the day it came down, covered in dust, sand and grit. Compare the bakelite grip on the control column with ours and you will see that they are identical! Photo: Jakub Perka

The gunsight switch seemed like a good place to put the “guns-at-the-ready” photo of Copping taken in North Africa. Photo: Dave O'Malley