GLASGOW’S OWN — Honouring Harry Hannah

Harry Hannah, is a friend of mine. He was a Spitfire pilot flying for 602 City of Glasgow Squadron, one of the most vaunted and storied fighter squadrons of the Second World War. Some of the greatest and most highly decorated aces of the aerial war were also in the same ranks as Harry at 602 including Squadron Leader James Harry "Ginger" Lacey DFM & Bar, Free Frenchman Pierre Clostermann, Grand-Croix, Croix de Guerre, DFC and bar, DSC, Silver Star, and Air Medal, Wing Commander Brendan Eamonn Fergus “Paddy” Finucane, DSO, DFC & Two Bars, South African Johannes “Chris” le Roux, DFC and two bars, Air Vice Marshal Alexander Vallance Riddell “Sandy” Johnstone CB, DFC, AE, DL,and New Zealander Air Commodore Alan Christopher "Al" Deere, DSO, OBE, DFC & Bar.

Harry's story equals any one of these great men, though he was not offered the accolades, gongs and gazetting heaped upon these heroic men. Harry's story is one of survival, determination and heroism in the face of deprivation and malevolence. Harry's story is one of dreams realized, of achievement unheralded, of greatness untold, of sadness unhealed.

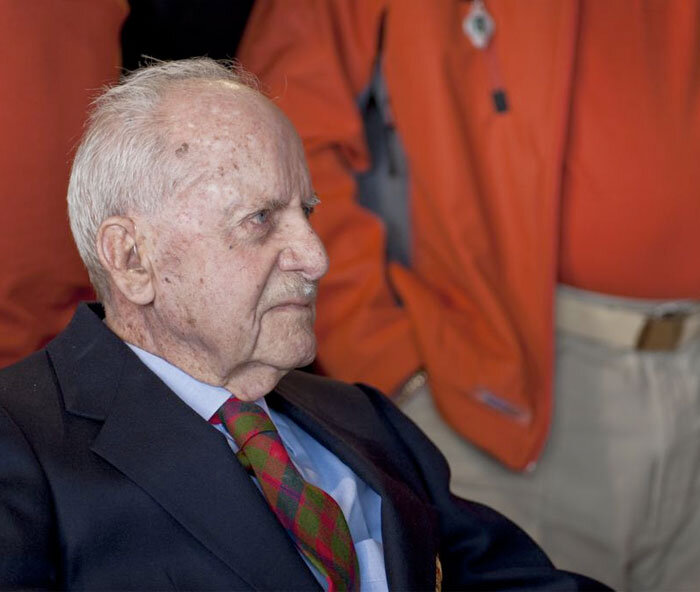

If you met Harry, you would not know he was 92 years old. He carries himself with dignity and delight, humour and sartorial elegance. He is a man of few words, but great kindness. He is a man for men–imbued with humility, great sporting skill and a discerning eye for the ladies. He speaks highly of you if you deserve it and not at all about you if you don't.

On May 12th, 2012 we had the phenomenal opportunity to dedicate our Boeing Stearman in the presence of Harry Hannah and his wife Yvonne. I had the opportunity to address the volunteers during the dedication and the following is his story. Being our annual Volunteer Training day last weekend, I took a few moments to talk to about volunteering at Vintage Wings and to honour Harry, a volunteer from a different time.

When we first opened this hangar more than 5 years ago, we were a small group of people, a small collection of beautiful aircraft and a large, modern and somewhat empty hangar. We had no plan, no goal, no predetermined mission, no idea that someday in the very near future we would be all of this. From that point forward we were completely and utterly in climb mode… never leveling off, never slowing, just moving forward and upward and upward and we haven’t stopped yet

From day one, our open doors attracted visitors, and amongst the curious onlookers we found knowledgeable acolytes who wanted to volunteer and slowly men and women came forward to volunteer their time, their skills and their passions. The next year we were forty, the year after 80, the year after that 120 and so on until today.

If you ask any of our pilots who were military flyers, no matter if they were Snowbird leads, test pilots or line pilots, Vintage Wings of Canada is a pretty fair substitute for the addictive camaraderie and need for speed fix found in combat ready squadrons anywhere.

The squadron is a group of men and women who share the stress, the labour, the shocks and the friendship of military life while carrying out a very complex and difficult mission. They give 150% at all times. They see excellence and the give excellence. They never let their squadron mates down. They have each other’s back. They share a common goal. They will ask for nothing back in return save the respect, trust and admiration of their peers

In this way, Vintage Wings of Canada is indeed a squadron in every sense of the word and as volunteers you all will play a vital role in the successful execution of its multi-faceted mission.

Like line pilots in combat ready squadrons, you have every right to claim that you are special, that you are an elite, that no one else is a good as you and your mates, that you have a common bond that will endure for the rest of your days.

For you to make these claims, we ask you to pay a price as a volunteer - in time, in effort and for some – even money. But the price you will pay to be part our squadron elite pales in comparison to the price paid by the volunteers of Allied Air forces during the Second World War. They volunteered to undergo daily threats to their lives, to endure deprivation, to ache from loneliness, to submit to disease, to respond to unending pressures to perform and for many to forfeit their very limbs and lives.

I would like to introduce you to one such volunteer who, in 1939, stood up with his generation, raised his hand and volunteered to join the Royal Air Force. Leading Aircraftman Harry Hannah, of Glasgow, Scotland, who had previous experience in the “Motor Trade”, signed on to 602 City of Glasgow, his local Auxiliary squadron. For the first couple of years, Harry was an engine fitter, servicing and repairing the Gloster Gauntlets and Spitfires of his squadron.

But Harry longed to fly and he applied for pilot training and was accepted. While the large bulk of RAF student pilots received their flying training at bases in England and here in Canada, another group were trained in America. Harry was to become one of these. In 1941, Harry made the extremely dangerous crossing of the Atlantic aboard the captured French liner Louis Pasteur during the peak of the submarine war known as the Happy Time to the U-boat crews. The journey took 9 days of endless zigging and zagging at top speed. Harry landed at Halifax and journeyed to Toronto.

Harry crossed the Atlantic in October of 1941, a dangerous time for U-boat activity. Here we see Louis Pasteur alongside the quay at Halifax in 1942. Due to her speed, as a troop transporter, the Pasteur normally made her crossings alone, not as a member of a convoy (without a warship escort). She made a voyage from Glasgow to Halifax (This is very likely Harry's voyage.) with a various complement, including officers arranging the 20,000 British troops’ transport across Canada and the Pacific to Singapore in October, 1941.

Harry landed in Canada, travelled to Buffalo and crossed the border as a civilian student wearing a recently issued grey flannel suit and carrying a cardboard suitcase - his “student” disguise. In the summer of 1941, America had yet to join the fighting war, but had constructed six large training bases for the RAF across the deep south from Clewiston Florida to Lancaster California. At these bases, RAF trainees were taught by civilian instructors in an all-through system. This meant trainees would remain at the same base for their elementary as well as service flying training, earning their coveted wings at the same airfield upon which they first soloed. There were in fact five different training schemes for RAF fliers commenced in the US prior to Pearl Harbor.

1) RAF (or UK) Refresher Schools. 3 or 4 sites accepting and qualifying US civilian pilots and washed-out USAAC cadets for RAF and RCAF service – initially funded by the UK and then through Lend-Lease (1940/42).

2) The Arnold Scheme for RAF students – funded by the USAAF (June 1941 to late 1943). Named after General Arnold who first offered the program during a visit to the UK.

3) The Towers Scheme for Fleet Air Arm (including some from New Zealand) and RAF students - funded by the US Navy (1941 to 1944). Named after Admiral Towers.

4) The British Flying Training Schools for RAF students – This is how and where harry was trained – funded through Lend-Lease (June 1941 to August 1945 – though some of the seven schools had a shorter life span)

5) PAA at Coral Gables, Florida for RAF navigators, funded initially by the UK and later by Lend-Lease (March 1941to October 1942).

6) Training the initial Boeing Fortress crews for No.90 Sqdn & TWA training crews for the ferrying of B-24 Liberators to Canada and the UK – possibly funded by the USAAF.

Three days after crossing the border at Buffalo, Harry found himself at a commercial airport called Falcon Field in Mesa, Arizona. Falcon Field got its start prior to World War II, when Hollywood producer Leland Hayward and pilot John H. "Jack" Connelly founded Southwest Airways with funding from friends like Henry Fonda, Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, James Stewart, Hoagy Carmichael and others. Southwest Airways operated two other airfields in Arizona -- Thunderbird Field No. 1 and Thunderbird Field No. 2 (now the site of Scottsdale Airport) -- to train pilots from China, Russia and 24 other Allied nations. Falcon was to be Thunderbird Field III and would train British pilots.

But the British said they'd like the field to be named after one of their birds, and thus Falcon Field was opened as the No. 4 British Flying Training School (BFTS). There were six BFTS airfields in the U.S., in Florida, Oklahoma, Texas, California and Arizona.

In September 1941, the first cadets of the British Royal Air Force arrived. They trained in Stearman PT-17 biplanes and North American Aviation AT-6 Harvard monoplane trainers. The good weather, wide-open desert terrain, and lack of enemy provided significantly safer and more efficient training than was possible in England. Even so, twenty-three British cadets, one American cadet and four instructors were killed in training and are now buried in the Mesa City Cemetery, along with several of their colleagues who have since died of natural causes. Several thousand pilots were trained there until the RAF installation was closed at the end of World War II.

The weather conditions at Falcon Field were conducive to round the clock flying training. Here an RAF flying student (the white flash on his hat is the clue) looks as a rare bit of dodgy weather looms overhead.

Related Stories

Click on image

Falcon field-based AT-6A Texans form up for a nice shot during training in Mesa Arizona. Only one aircraft wears USAAC markings at this ostensibly civilian facility.

Falcon field could be a hot as a skillet in the summer, something most British-born airmen had trouble coping with. To help them deal with it, they made extensive use of the base swimming pool.

It was here that Harry soloed on the Boeing Stearman in just 5 hours, and went on to earn his RAF wings in America on the AT-6 Texan. In all, Harry spent an entire year at Falcon Field, flying, studying and going to dances. A quick search of historical documents about Falcon Field shows that Harry was remembered by some of the local women folk as a gentlemen and a great dancer.

Harry then risked his life again to cross on another troopship, RMS Warwick Castle of the famed Union Castle Line, through U-boat infested waters to join his fellow pilots on the 602 Squadron flight line. Shortly after Harry's crossing, Warwick Castle was sunk by U-boat in the Mediterranean Sea.

Harry had hoped to join up with 602 after the crossing and a stint at a spitfire OTU, but first he had to languish about at a gunnery school as a staff pilot flying a Fairey Battle and towing target drogues for fighter pilots. Harry describes the Battle as “Twice the size of a Spitfire with the same engine... you can imagine the lack of power.”

After three months in the purgatory that was gunnery school, Harry finally was sent to his beloved 602.

Harry spent the six months flying on fighter operations with 602 Squadron “Glasgow’s Own” until July 15th, 1943 when, returning to RAF Kingsnorth from a mission escorting 12 Douglas Bostons to Poix, France, he heard the frantic radio calls from a Boston under attack behind him. Almost home, Harry and his leader turned hard, back over France. In the precise moment of the turn, Harry’s engine took heavy hits from cannon fire from an unseen German fighter. Immediately, Harry's canopy was smeared with hot brown engine oil. With no engine, and no way to see where he was going, Harry had no option but to hit the silk. He yanked hard on the ball hanging at the front of his canopy. This would supposedly free the canopy and it would sail off allowing him to climb out. Unfortunately, the ball came away in his hand when the rusted cable snapped from his yank. Now he was desperate as the clipped-wing Spitfire Vb entered a tight spin downward.

After a few terrifying moments, he managed to slide the canopy back against the g-forces of his spin, remove his helmet and disconnect his radio. Undoing his harness, he dove outward just missing the tail of his Spitfire. His canopy blossomed when he pulled the D-ring and he had what he describes as the most peaceful and quite moment of his entire war– dangling beneath a swinging canopy of nylon looking out over the English Channel towards home and down to the beach and tidal flats that comprised the mouth of the Abbeville Canal at the Somme River delta.

A quick look at Google Maps brings us a fine view of the mouth of the Abbeville Canal - the straight line running from Abbeville in the lower right to the delta that is the outflow of the Somme River. It was here that Harry was shot down on the beaches along the Channel.

Harry shattered his ankle in the jump. His Spitfire was burning not far away. So was his flight leader's Flying Officer Strudwick's. “Struddy”, as Harry calls him, was also hit by the same raking of cannon fire. He also was gathering up his parachute in the sand flats of the Somme delta. The Frenchman who first got to him, smiled and told him in English and French“For you, La guerre est fini”

When Harry was shot down in 1943, he lost all of his personal records, log book, and many photographs. After two years in prison, those important documents of his RAF service would never be found. The few images that he did have that survived the war, were loaned to a squadron mate to be copied. That was the last he saw of the remaining photos. Harry has no images of himself in service what-so-ever. However, a bit of luck and a a few hours of digging on the web, and I came up with a few images of Harry amidst his squadron mates.Here we see the pilots of 602 City of Glasgow Squadron in England in the summer of 1943, just weeks before Harry was shot down. Harry and his Flight Leader Flying Officer Strudwick (right) are clearly identified. Both men were shot down simultaneously when turning back to France. They parachuted to the beach next to the mouth of the Abbeville Canal and landed only a couple of hundred yards apart. Also in the picture is Harry's best friend, Sergeant Jimmy Kelly, sitting right next to him, leaning on him almost. The one thing Harry still fusses about from the war, the one thing that still makes him sad and angry today is how Jimmy died. A year after Harry was shot down, Jimmy crash landed his Spitfire in France after D-day. He was dragged out of his cockpit and at the orders of the local commander, was summarily executed. Jimmy went through everything that Harry did... from ground crew to Falcon Field to troopships to 602. You can still detect powerful emotion in Harry's voice 70n years after the atrocity. When I look now on Harry and Jimmy in the photo, I see love and friendship and I want to weep for them.

When this photo was taken, Harry was already in prison. Taken at RAF Detling in Kent, the caption indicates this is 1944. This would have been one of the three stays at Detling the squadron had between January and April of that year. Jimmy Kelly is second from left at the top row in the wedge cap. 602 Squadron photo

Looking further on the web, I came across this image from the Imperial War Museum which shows Flying Officer James W. “Jimmy” Kelly's temporary grave next to the Spitfire he he crashed landed in. Other reports found on the web indicate that Jimmy was flying No.2 to famed Free French ace Pierre Clostermann when he was shot down and murdered. Kelly was one of two Spitfire pilots of No 602 Squadron shot down by FW190s over Normandy on 4 July 1944 ( the other was Flight Sergeant L H Chaldice). The squadron lost four more aircraft that month, all to light flak while strafing ground targets. None of the pilots survived.

Well, Harry’s war finished–far from it. After recovering in a German-run hospital in France, he was shipped east to a series of POW camps. At the notorious camp known as Stalag Luft 4, in what is now north western Poland he and a fellow prisoner broke into a camp administration building at night to steal a camera to use for escape document photos. Sneaking back to their barracks they were seen and his buddy was captured. Harry escaped immediate capture by hiding under a truck. He remembers well the boots of one of the camp guards standing next to the truck and the heaving breathing of the soldier trying to find him. He got back to his barracks that night, but his friend was delivered a day later beaten and toothless. The guards simply demanded the camera back from Harry. Both were shipped by train far to the south to the city of Dresden, near the border with Czechoslovakia.

It was in Dresden that he faced a court martial for what was deemed a criminal act - the theft of the camera. Both he and his friend faced four years of hard labour, but his Wermacht-appointed lawyer, a young officer who spoke perfect English, defended the eloquently, saying that this is what they (the Wermacht) would hope their own soldiers would do if captured. His punishment was commuted from hard labour, a sure death sentence, to a long, cold, lonely, year in solitary confinement in a concrete cell. In 1945, after two years in prison, Harry was freed by liberating Russian troops. Harry made the long overland journey by boxcar with other freed Allied servicemen to the port of Odessa on the Black Sea where he boarded a British troopship for the return to England. Learning that he was now a Warrant Officer, he traveled in style back home.

Of course, Harry's war was far more complex, far more eventful and far more detailed and colourful than these few notes can ever portray, but that full story will come. Last year Harry was convinced to write down his memories of a life with 602. They fill the pages of a scribbler notebook - painstakingly written in block letters in pencil. I hope to transcribe them over the next months.

Harry emigrated to Canada after the war and spent a life with the Ford Motor company – seven years in Africa and seven more in South East Asia.

Harry, my friend… for volunteering to fight, to face the U-boat wolf packs not once by twice, for flying on operations for a year, for attempting to save that Mitchell crew, for your shattered leg, for your two years in prison, your bearing witness to the horror of Dresden, for your lost year in solitary confinement and the loneliness you endured, for your humility and grace under duress, we dedicate our mighty, our steadfast Stearman in your name. With it we hope that your memory and that of your friend Jimmy Kelly* will be carried aloft for all the unsung heroes.

Long may she fly

The famous Free French fighter ace, Pierre Clostermann wrote a very successful book, The Big Show (Le Grand Cirque), on his experiences in the war. One of the very first post-war fighter pilot memoirs, its various editions have sold over two and a half million copies. In it he describes in detail the action which resulted in the death of Harry Hannah's best friend Jimmy Kelly. Here, translated from the original French by Vintage Wings of Canada's volunteer and translator Pierre Lapprand (also from France), is a transcript of that passage.

5:30 p.m.

A patrol of six Spitfires is flying at treetop level, the group is divided into two sections.One of the two aircraft is responsible for destroying ground targets. Another four must provide air cover. This section of four Spitfires is led by Pierre Clostermann, his winger No. 2 is Jimmy Kelly, his No. 3 Bruce Drumbrell and No. 4 Mouse Manson.

As the group approaches its goal, there is a convoy of vehicles near Beny-Bocage. Jimmy tells his leader two enemy aircraft at their eleven o’clock. The four Spits are already in combat formation. Arrived at 3000 meters distance, Clostermann identifies the two bogies being Fw-190s. He orders everyone to dump the extra fuel tanks and the four Spitfires push the throttle. He warns his Squadron Leader who leads the ground attack section he will engage both German aircraft but does not get an answer back from him.

1000 meters.

The four Spitfires climb vertically in formation to intercept the Fw-190s flying just above the trees. But the Germans immediately spot the Clostermann group. They also climb vertically getting closer to the Spitfires. Both Fw-190s want to engage with the four Spitfires. But while the advantage is definitely to the Spitfires continuing to fly above the German aircrafts, an unexpected event occurs.

The Squadron Leader’s ground attack section cut the path to the four Clostermann Spits, therefore to avoid the collision, Clostermann and his wingmen break their formation while the two Spitfire assault section fly straight as if they didn’t have seen anything.

The two Fw-190s did not ask for better. They push the throttle, climb vertically and engage the combat with the six Spitfires. That manoeuvre is so outstanding that Clostermann is left speechless, but he also understands that the two German pilots are anything but rookies.

While Clostermann lost any offensive advantage, he tries to reposition himself in a better position. In response, he sees one of the two Fw-190s coming straight to him, face to face, he only has a second to push the stick and fly under the belly of the German fighter.

Clostermann pulls up just above the treetop, stick against his belly and full rudder, he turns on the wing to try to catch up with the Focke-Wulf. While still turning, Pierre Clostermann watches an explosion near a farm.

The debris of two Spitfires are flying everywhere... The Fw-190s came down to the ground attack section, Squadron Leader of 602 Sqn and his wingman did not have a chance.

For the four Clostermann Spitfires section, it’s the stampede. The Spits are totally outclassed by the two Focke-Wulfs, the Germans are like two cats playing sadistically with four mice. One of the Spitfires, already hit, managed to gain cloud cover, and it outwits the Fw-190 that hung on his six o’clock.

Clostermann committed to engage, both go into a tight turn but the Fw-190 turns shorter, his BMW-801 outperforms the Rolls-Royce Merlin.

Impossible to keep the German in the collimator.

But Clostermann is trying to take over when he hears in his headphones:

"Hullo Section Max Red, Red Two here, please help me, I've had it!" This is Jimmy's faithful winger who called for help. But the two Germans are “swords”, the second Fw-190 remains in contact with Clostermann to prevent him to go help his friend, leaving the first Focke-Wulf deliver the coup de grace.

Clostermann finally manages to escape from the Fw-190, he makes a break so tight that the Spit stalls, he catches him flush at treetop level by doing a half roll recovery. The Fw-190 passes through the collimator. A burst. The Fw-190 skidded on the wing and out of the range of Clostermann’s machine guns. Missed!

In an attempt to regain the upper hand, Clostermann performs an Immelmann, but this time it is German flak unleashing against him. Full throttle toward the clouds, ceiling is low, the Spit disappears in the layer.

Clostermann looks at his watch, this is just one minute since they engaged in combat and both Fw-190s have disappeared. As he looks around, Clostermann sees passing before him a Spitfire in a shallow dive, the propeller at idle.

It is his number 2. He calls on the radio - no answer. It gets closer and he sees his friend, head forward. The fuselage was riddled with holes. The Spitfire increasingly accentuates its dive, and then strikes the ground.

Clostermann returns alone, his throat is dry. When he arrives at Long Field, near Arromanches, he sees along the runway a Spitfire that crashed. A quick glance, the number 3 Bruce Drumbrell is safe. But they are just two.

Today the enemy and two Fw-190s were the strongest. The two German fighters shot down four Spitfires returning without any damage.

The Harry Hannah Boeing Stearman sits polished and waiting for it official debut and her first meeting with her namesake, Oakville, Ontario's Harry Hannah, formerly of 602 Squadron. Photo: Peter Handley

Before the dedication, Harry gets a quick tour of the Stearman, commenting “They weren't this clean when I flew them. Photo: Peter Handley

With Harry and his wife Yvonne sitting in a place of honour and comfort, the volunteers of Vintage Wings of Canada gather around to hear Harry's story. Photo: Peter Handley

Harry's story is of course just one of many, many thousands of stories of airmen during the Second World War. His story is however a powerful tale of many unique aspects of the pilots experience during the worst conflict in recorded history - U-boat threats, training under the Arnold Plan, Target Towing, fighter ops, bailing out, POW camps, solitary confinement, the bombing of Dresden, and finally salvation. The story as told, clearly has the volunteers riveted. Photo: Peter Handley

Harry rises to speak while Carolyn Leslie, always remembering the details, presents Yvonne with yellow roses representing the Vintage Wings program known as Yellow Wings. Photo: Peter Handley

Harry is a man of few words, but they were words of honour, humility and gratitude towards Vintage Wings of Canada and our work to preserve the memory of Harry and his mates. Harry's wears his pride in his squadron with a City of Glasgow tie and a 602 City of Glasgow Squadron badge on his blazer. The Squadron badge sports a red lion surmounting a white St. Andrew's cross... spawning the Squadron motto: Cave leonem cruciatum – "Beware the crossed lion". Photo: Peter Handley

The Warbird Pilots. While most of the Vintage Wings pilots were tied up in Formation Camp briefings, four flyers were in attendance including (L-R after Harry) Rob Fleck, President (Sabre, Mustang, Harvard), Todd Lemieux, (Stearman, Cornell, T-28), Rick Volker (Sukhoi) and Dan Dempsey (Sabre). Photo: Peter Handley

Harry (centre) is surrounded by the Vintage Wings Team, who were honoured to share the same hangar floor with the humble former Spitfire pilot. Photo: Peter Handley

70 years after his last flight in a Stearman, Harry still shows the youthful excitement and steely-eyed fighter pilot determination men of his generation became famous for. Photo: Peter Handley

After the dedication ceremony, Calgary's Todd Lemieux, tasked with getting Harry back into the Stearman Spirit, briefs him and Yvonne on the route they will take back in time. Photo: Peter Handley

Two of Vintage Wings' most-loved pilots, Todd Lemieux and Francis Bélanger share a laugh with Harry before he suits up. Bélanger is a highly experienced, carrier-qualified F-18 fighter pilot who, in addition to flying our Cornell and Corsair, is the check pilot for the Stearman. Photo: Peter Handley

Harry's ride for the morning is rolled out onto the ramp. Photo: Peter Handley

Suited and helmeted, Harry has a moment with his memories. Photo: Peter Handley

Harry and Todd go over the controls and dials, with Harry beginning to remember his training days. Though 70 years old, the memories begin to become clearer and the fog of a long life starts to dissipate. Photo: Peter Handley

Todd finishes up his briefing, and Harry is ready to go. Photo: Pierre Lapprand

Lemieux starts the Harry Hannah Stearman and the Continental barks to life. Photo: Peter Handley

Lemieux begins taxiing and Harry's heart is most surely soaring. Photo: Peter Handley

Out to the hold position at the intersection. Photo: Peter Handley

Lemieux and Harry run up while a group of Formation Camp fighters rolls up to join them. Photo: Peter Handley

As Harry takes off, Paul Kissmann in the Corsair and Bruce Evans in the Trojan look on. Photo: Peter Handley

Back in the big ole Stearman sky after 70 years, Harry carries our hearts with him. Photo: Peter Handley

At 500 feet, Lemieux hands over control of the Stearman to Warrant Officer Harry Hannah, and for the next 30 minutes he banked and climbed and soared like he was 19 again. Todd would later add on his Facebook page “He took the controls and flew like it was yesterday. It was a great honor to fly with him.” Photo: Todd Lemieux

The two aviators reluctantly have to return to earth. Photo: Peter Handley

The look on Harry's face says it all... a look in which we alternately see strength, joy, pride, and gratitude. Photo: Peter Handley

xThe two aviators from eras seven decades apart offer a thumbs up for Handley's camera. Photo: Peter Handley

Harry heads for the arms of his Number Two. Photo: Peter Handley

Afterward, Harry and Yvonne toast the successful mission with a cold beer. Photo: Peter Handley

Westward Ho!

The day after Harry's flight, at first light, Todd Lemieux and Dave Maric strapped into the Harry Hannah Stearman and headed west to tell the story of Flight Sergeant Harry Hannah and 602 Squadron. The Stearman will now live in Calgary where it will be the nucleus of Vintage Wings West, the western franchise of Vintage Wings of Canada.

Maric and Lemieux fly up the Ottawa River Valley past Chalk River on their way to Sudbury. Photo: Todd Lemieux

In the dying light of Day One in their journey westward, Dave Maric captures a magnificent moment - one of many that pilots and passengers will experience aboard the Harry Hannah in the years to come. Of this day, Lemieux said, “The wilds of Northern Canada roll by our Stearman, framed by the yellow wings in an ever changing montage of lakes, trees and rivers. The open cockpit provides a unique and dynamic view. With the wind in your face, the smell of the trees, the water, forest fire smoke and the airplanes spent oil and exhaust, it is a tactile, olfactory and spiritual event. To experience it is like nothing else you've ever done. Words like awesome, beautiful or even wonderful do not do it justice. It is quite simply, life changing. — with Dave Maric”. Photo: Todd Lemieux

On a fuel stop, Dave Maric regales a rampie with the story of Harry Hannah. Photo: Todd Lemieux

Somewhere over the North Shore of Lake Superior, Maric tilts a wing so that Lemieux can photograph a remote archipelago. Both men are grateful for the opportunity to combine adventure flying with relating our aviation history to fellow Canadians. There are no better spokesmen for Harry than Maric and Lemieux. Photo: Todd Lemieux