In Search of Lost Values

It’s New Year’s Eve 2015. It is a time for reflection and gratitude. For men and women of my parents’ generation, New Year’s Eve holds a special meaning. As they worked their way through the deprivations of the Great Depression and the horrors and losses of the Second World War, the end of a year was a symbol of hope for better things to come. It was a chance to put the pressures and unhappiness of the previous year behind and, for a few days at least, live in the hope that a job would be found, that life would improve and that children would be coming home alive from the war.

I got to thinking about that generation, about what they went through, about what our children might have to go through and how they will build a life for themselves. I’m not saying that they will have to face the same tribulations as the “Greatest Generation”, but they will need the same virtues to guide them along their way—qualities that might seem outdated to some.

During the lead up to this Christmas time, there was an ad campaign for a chain of electronics stores here in Canada called The Source. This particular campaign outwardly mocked simple, uncomplicated and handmade gifts and ended with the company’s new tagline… “I want that!”

Every time I watched that commercial, I grew more and more pissed, more and more disturbed by its message. I suppose it’s just the world we live in, but it felt like a cynical play to the sense of entitlement that many young and old people have these days. It was so nakedly and unabashedly a pitch to greed, to consumerism, to materialism and to fulfillment of desire over need. This “I want that!” tagline had all the emotional and social maturity of a small spoiled child before he or she has been taught the values that we all should hope they will one day embrace. To consume is natural, and it underpins our economic structure. By consuming food and products, we build and strengthen industries, create jobs, support our society. But there is a line between a consumption that fulfills need and a gluttony of material possessions that results from an addiction to “want”. Everything these days is a consumable and I am as guilty as the next person of having more than I need… MUCH more than I need.

There was a time in recent memory when consumption and celebrity were at the bottom of most people’s lists of the important things, while belonging to a community, love of family and creating something lasting were at the top. This belonging to a wider community—family, neighbourhood, church or country—bred men and women who, though succeeding in life, did not put themselves at the centre of it. They were resilient, ready to help, environmentally lean, careful with their money, attentive but not indulgent to their children, and willing to sacrifice—for their families, their communities and their countries. Sadly, today, the reverse is true. It is the age of the selfie, of fame for being famous, of sexting and texting, of avatars and false identities and a myriad of norms and phantom goals that serve to detach us from the place where we belong.

There exists a great divide between the generation before me and the one after me. Both have to face or had to face a world that was becoming a more dangerous place by the minute. Both have come out of a period of economic hardship. Both were or are heading into an uncertain time, a vicious and wobbling world where one might think twice about raising a family. I can’t help but think that the link between my father’s generation and my children’s is me… is us. History tells us that our parents had what it took to make it out of the world of darkness and create a new world—a world that quite possibly we, their children, screwed up. Thanks to our parents, our world was a soft one. It was a world of relative peace, of unchanging social complexion, of warm houses and three squares. We were taught virtues by our parents—the ones that got them through a world on fire—but we never really had to employ them to save ourselves. Now I wonder, as I know you must also, whether our children have had, in us, their parents, a fine example of how to live. Have we given them the tools to build a good family, a just society, a strong economy and a better world? I am not sure.

Over the years that I have been involved with Vintage Wings of Canada, I have had the remarkable good fortune to meet, befriend and research the lives of a number of very fine men from around the world. All of these men were veterans of the Second World War. Some I consider my friends. All of them have affected me very deeply. Some I can honestly say that I love—as simple and complete as that.

There was Arch Simpson, a Kittyhawk pilot from Australia—kind, thoughtful, at peace with himself at the end. A storyteller of great humility. There is Hugh Bone, a Hampshire-born Mosquito pilot living in Göteborg, Sweden—kind, direct, warmly nostalgic, loyal, and lively, he is a pleasure to write to and call a friend. My heart aches a bit when I think of my friend and Spitfire pilot Dr. John Bennett—humble, pacifist, mannerly—who balanced the killing he was required to do in the war with the delivery of a new generation of babies after it. I smile when I think of Spitfire pilot Fred Jones of Kincardine, Ontario—precise, patient, soft spoken, fatherly. There was Sabre and Voodoo pilot Ron Poole from Chemainus, BC—in love with his wife, facing cancer with dignity and humour, full of stories and “skits”. So many, so great—so few now.

Some evenings after three fingers of scotch, I look back over the stories I have written of these men and the powerful influences they have had, and I now begin to think that they have much still to teach us. Six of these men I have chosen for the powerful lessons they have taught me. These lessons are the lost values or virtues of my youth, the ones I know my father and mother taught me; the ones I hope I have passed on to my children; values that in today’s lexicon seem oddly outdated—Humility, Duty, Courage, Leadership, Sacrifice and Dignity. These are values I wish to exhibit myself, but I know in my heart I have never been challenged enough to truly display them in a meaningful way.

So, if you will bear with me, I have chosen these men, these friends, to exemplify one of these seemingly lost qualities a young man or woman should have. Four of these men I have known personally, four of them earned their wings right here in Ottawa, two of them died in the war. Two of them are still alive and healthy. All of them I have thought of as friends. All of them are fine examples of any of these six virtues. They have answered the call of a duty, made sacrifices, shown exceptional leadership, exhibited great courage and, despite these accomplishments, have remained so very humble and so wonderfully dignified.

HUMILITY — Flight Lieutenant William Robertson “Bill” McRae, 401 Squadron, RCAF

The last time I saw Bill McRae, he was smiling ear to ear—like the twenty-year-old Spitfire pilot inside his 92-year-old body. It was the night we honoured him with a banner, bearing his name and youthful visage and accompanied on its way to the ceiling of our hangar by a piper playing the Air Force March Past. It was our way of telling him how much we loved him and how much he was revered for his accomplishments during and after the war. Though Bill would never have blown his own horn, the look on his face told us how much he appreciated the gesture and how much he enjoyed the warmth he felt in his heart and the meaning it gave him at the end of his life. Bill died two months later of cancer. He knew he was dying on the night of his surprise tribute, but he never told any of us. He was humble to the very end.

This is something that Bill McRae and most of his mates share. Whether they hail from Canada or Australia, the United Kingdom or the United States, the veterans of the war have, by some unspoken and mutual agreement, decided that the terrible things that happened to them during the war, that the deaths and injury to their friends and their shared sacrifice would be dishonoured if one man were to brag or gain heroic status by self aggrandizement or self-promotion. Almost to a man, they share their stories only with each other and with those who take the time to understand the context of their suffering and open doors to their memories ever so slowly.

Related Stories

Click on image

Bill was a Spitfire pilot with 401 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force. He flew Spits in Scotland, in the south of England and throughout France and Belgium following D-Day. At one point, Bill flew at least one combat sortie on 60 consecutive days leading up to, during and after D-Day.

Bill did what all the reluctant warriors did at the end of the Second World War—he went home and got back to what he was meant to do before the Nazis upended his life. He married Mary Denholm in 1946 and had three children—Wendy, Ian and Marilynn. The war was a dangerous endeavour, one he was lucky to survive. Upon return home, he took up a safer pursuit—explosives. Bill spent his entire working life working in the Explosives Division of Canadian Industries Limited (C-I-L)

Most veterans of that war would take their stories to the grave, but there are just a few with the gumption, the time and the reasons to tackle these memories, to sift through them, to bring out the best of the men, the friendships, the shared terrors and miseries and put them down in words. Bill found a voice after retirement—a humble voice that spoke with the collective voices of all of his mates—and began writing elegant historical vignettes for the Canadian Aviation Historical Society, its Newsletter and Journal. His considerable body of work—at times wistful, gently humorous, poignant and always humble, has provided lessons in writing to many of us—observant and detailed, without putting himself at the centre. While the stories were about his experiences, they were never about him. Courageous and dignified, Bill exemplifies all lost values, but humble was how we knew him.

DUTY — Pilot Officer David Francis Gaston Rouleau, 131 Squadron, RAF

I strongly doubt that, as a child, David Rouleau would ever have thought he would become a fighter pilot. Photographs of him with members of his Lisgar Collegiate drama club show a young man with soft features, receding hairline, wispy hair and an expression that showed a young man unsure of himself, yet possessing a quiet sense of humour. Despite his softness, there was a hint of pain and a sense of hard-bitten experience upon his countenance. If you were to pick a man to be a fighter pilot based on looks alone, he would not be the man you chose.

David was an only child, living in Ottawa with his widowed mother in the house of her father, along the historic cut that is the Rideau Canal. His family was from the upper-middle class, his grandfather having been Deputy Minister of Justice for Canada as well as a much respected Parliamentary Counsel. David summered along the shores of the Gatineau River near Wakefield, Québec, played golf at Larrimac Golf and Country Club and shared the long, hot summers with his cousins. His closest companion in these heady days was his cousin Peg. Upon graduation from high school, he attended the University of Toronto working towards an Arts degree.

Considering his love of the theatre and literature, I suspect that David would have chosen a career as a teacher or perhaps a journalist. As a teacher, I believe he would have been dedicated, kind and inspiring. We will never know how his life should have turned out, for on the bright Mediterranean morning of 3 June 1942, David Rouleau, the quiet, demure boy in the drama class, flew a 2,000 horsepower Supermarine Spitfire from the heaving deck of the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle, bound for the embattled island of Malta.

He went in the company of 8 other pilots in unarmed Spitfires equipped with long-range “slipper” tanks. His only goal was to reach Malta and deliver himself and his vital aircraft safely to the island, a few hundred miles to the east of Eagle’s position. He never made it.

David Rouleau and three other Spitfire pilots were shot from the sky. They had the misfortune of running into the Messerschmitt Bf.109s of one of the most experienced and deadly Luftwaffe fighter squadrons in the Mediterranean Theatre. It is difficult to piece together the last glorious hours and the final violent moments of David’s life, but when his burning Spitfire struck the surface of that great blue sea, he and his future were shattered and ruptured and his story, his life, simply vanished. Gone.

There were short column inches in the Ottawa newspapers no doubt, perhaps a mass at his church. There were tears and most certainly the girls he once admired now saw him in a different light. His mother remarried at the end of the war, time passed and David’s memory soon receded as life moved on. The pain remained in the heart of his mother, his grandfather and his beloved cousins, but in the decades that followed, he would cease to exist. A name on a plaque. A memory whispering on a summer wind through the trees along the Gatineau River.

David, who had so much to give, had done his duty. He lay on the line a future he had not yet chosen, and lost it. The road that was his life took a hard turn to his destiny, but, with his grandfather’s connections, he could easily have chosen an easier route, one that contributed to the war effort, but which kept him safe.

If you walk up the old and worn stairs of Lisgar Collegiate into the historic lobby of Ottawa’s first high school (1843), you will see two large bronze plaques mounted to the walls. Embossed on these plaques (one from the First and one from the Second World War) are the names of nearly 300 young men who lost their lives in battle. Three hundred from one high school! There were more than 2,000 Lisgar students who enlisted during these two wars—15% were killed.

These plaques bear grim witness to the obscenity and destruction of war, and to the honour of many, like David, who did their duty—a sense of duty to a wider community that took them to their deaths. Comparing the soft questioning face from his Lisgar yearbook to the oil slick and debris that spread out across the sea where his life ended, my heart breaks at the loss.

When thinking of David Rouleau and all the young men and women like him from this generation I am reminded of the words of Frederick Forsythe in The Shepherd, his hauntingly simple ghost story of an airman facing death—“It’s a bad thing to die at twenty years of age with your life unlived and the worst thing is not the fact of dying, but the fact of all the things never done.”

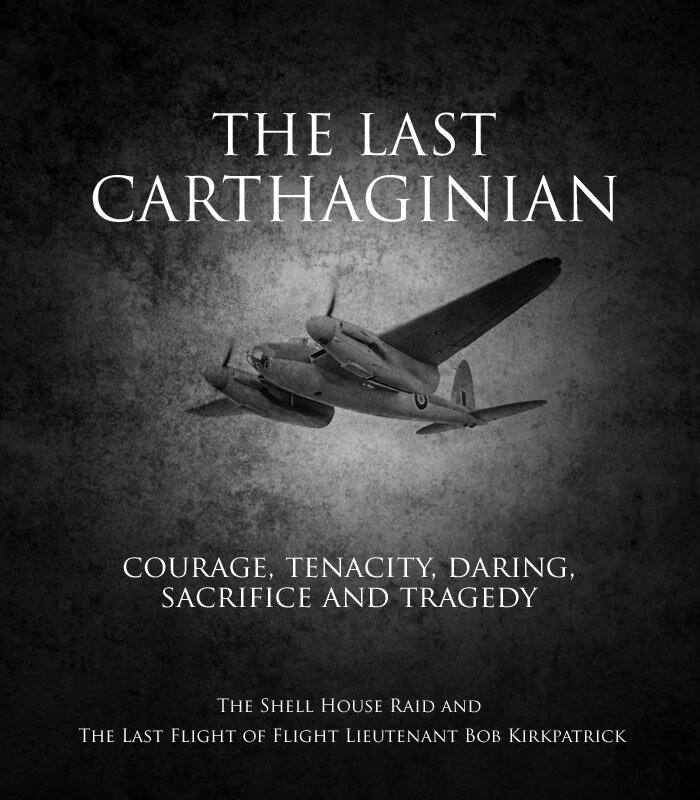

COURAGE — Flight Lieutenant Robert “Kirk” Kirkpatrick, 21 Squadron, RAF

The American-French author Anaïs Nin once wrote that “Life shrinks or expands in proportion to one’s courage.” I believe this deeply. The most powerful feelings about family, love and the simple beauty of just breathing are paired with the greatest fears and danger. It is the soldier pressing his body hard to the ground in a slit trench during a mortar attack who understands the love of his mother more than any man. It is the wounded pilot fighting hard to keep his battered and smoking Halifax bomber steady for home on three engines who fully grasps the true nature of the love of his fellow crewmen. It is the young American boy who, slipping out of the cockpit of his Mosquito and taking in a deep, fragrant breath of Norfolk County evening air, feels the life drawn back into his body and, in so doing, understands the great incongruity of those contradictory bed mates—fear and life.

All of the men in this story have displayed incredible courage in war and for those who survived, also in the manner in which they conducted their subsequent lives.

Flying Officer Bob Kirkpatrick, an American, was an officer and a gifted pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force. American to the bone, he was nonetheless very proud of his Canadian service and his Canadian wings. He served with the Royal Air Force’s storied 21 Squadron on Mosquito intruder missions of extreme danger, including Operation Carthage, the now legendary low level, precision bombing attack on Gestapo headquarters in central Copenhagen. The photographic imagery and film from that dramatic raid, some of which is on YouTube, was all shot from the cockpit of Bob’s “Mossie”, an aircraft he lovingly referred to as the “Queen of the Skies”.

The Latin motto of the Royal Canadian Air Force, and in fact all Commonwealth Air Forces, is Per Ardua ad Astra, which, in English, means Through adversity, to the Stars. So completely different than the more aggressive, jingoistic and somewhat less poetic motto for the USAF, Aim High … Fly-Fight-Win, this Haiku-like sentiment of the RCAF remains a perfect and poetic phrasing of the work, risks, losses and ultimate victories of this remarkable and storied service. It is deeply beautiful in that it lays out, in two simple and contrasting halves, the powerfully contradictory Latin root words of “Ardua” and “Astra”. This balance, this admission of the existence of both the horrors and the glories, is sublime.

It is a motto that could have been the personal motto of Flying Officer Robert Kirkpatrick, as he processed through his beautiful life until his death two years ago. Bob learned early on that Ardua came with Astra, hell with heaven, work with play, loss with joy, pain with love and fear with courage. Bob embraced the difficulties of life for the sweetness of their overcoming. This is the true nature of all experience, not just in times of war. It took a man who I had never met; a man from the heartland of America, not Canada, a man of 91 years and short future, to show me that courage can be called for and answered throughout life and not just, as we often think, in times of war.

Though Bob was in hospice care in Humboldt, Iowa, I had suggested he might think about coming to Hamilton where the newly-completed de Havilland Mosquito of Jerry Yagen’s Military Aviation Museum was making its Canadian air show debut. I did not expect that he would accept, but he did not dismiss the suggestion either. Instead he kept the possibility of such an adventure as a wonderful dream to help him through his painful days. We kept in touch via email and, thanks to his wonderful neighbours, Dave and Deb Dodgen, he made it all the way to Hamilton—a six-day trip in the Dodgen’s RV which they bought to bring Bob to see the “Queen”.

No one could fault a 91-year-old man fettered with a continuous pain management regimen, if he declined an invitation to attend an outdoor air show in the heat of summer, nearly 1,000 miles away. But Bob Kirkpatrick was a 91-year-old man on the outside, and a virile 24-year-old on the inside. He still thought like a young man. He still looked out upon life as a young man. He saw that the pain, the work, and indeed the risks, if faced, could pay out in silver dollars—in one more life-confirming experience, one more time to see an old gal named Mossie, The Queen of the Skies, who once took him to Hell through the Ardua and brought him back to enjoy seventy years of stars at night and more than 25,000 sunrises.

Bob’s courage to the very end of his life has been one of the greatest lessons of my life. His joy and pride transcended his pain and his fears of end of life. Supported by people who loved him, Bob passed away the following February, just days before his 92nd birthday.

LEADERSHIP — Lieutenant General William Keir Carr, 683 Squadron, RAF

There is an old saying that “At the Moment of Greatest Slaughter, the Great Avenger is being Born.” It is a beautiful, if somewhat dramatic expression, which simply means that out of times of stress and intensity, the greatest leaders are born. It was in this cauldron of anguish and menace, that the future leader known as the Father of the Modern Canadian Air Force was created from a young and fresh-faced Pilot Officer Bill Carr.

Carr completed his Elementary Flying Training on Fleet Finches at No. 22 EFTS at L’Ancienne-Lorette outside of Québec City. He did his Service Flying training on Harvards right here in Ottawa at No. 2 SFTS Uplands. His wings were pinned on him by no less a man than Air Marshall Billy Bishop. He flew Photo Recon Spitfires deep into enemy territory from bases in England, Malta, and Italy. Twenty-year-old Carr would strap himself into a Spitfire and deliberately take it deep into a Europe run by Nazis, the greatest evil known to modern man. In broad daylight, he would fly over their encampments, their anti-aircraft installations, their factories, their cities, their airfields, travelling at 300 mph, never positive that his oxygen system would continue to feed him life, or that his engine would continue to run in the thin air, always on the lookout for an attack. He did this 142 times. Each of these times, he would wake from sleep, eat breakfast, flight plan and ready his mind and body for a mission alone—a mission that could very likely end in his own death, far from friendly skies. To understand just how many times this was, I challenge you to start counting slowly from one to one hundred and forty two. I promise you that by thirty, you will begin to understand just how many dangerous recce sorties 142 really is.

Leadership is a pay it forward business. Great leaders beget great leaders. This great future air force leader had one of the finest role models imaginable in his Commanding Officer at 683 Squadron—Wing Commander Adrian Warburton, one of the most decorated RAF pilots of the war with no less than two Distinguished Service Orders and three Distinguished Flying Crosses!

Upon returning home, he spent a few summers with Bill McRae flying Norseman bush planes surveying the North of Canada. However challenging the work was there, it was perhaps the perfect way to decompress from years of hard flying and the deaths of so many friends. There was fishing, flying, camping and lots and lots of open skies for flying… with no enemy aircraft to ruin your day.

Following this period of decompression, Carr began a steady climb through the ranks until he came out on the very top as Deputy Chief of Defence Staff and ultimately as the first Commander of Air Command. Bob Fassold, himself a retired Major General and former Comet pilot on 412 Squadron at the time of Carr’s command had this to say about Carr’s leadership style: “He had very high and inspiring expectations and performance standards for all aircrew and squadron members. Consequently, we achieved such high levels on our own, that we not only took great pride in ourselves, but also in our 412 squadron mates, and especially our CO. Carr seemed then and still today to somehow quietly radiate competency and authority … and a high regard for the importance of everyone to the unit objectives. He never went around ‘commanding’… he just ‘did’… and clearly expected the same of you. Throughout his career, day in and day out, and to this day, he has set a glowing personal example of leadership in how to get things done right… sometimes even having to resort to unorthodox methods. In so doing he has contributed to the successes and enjoyment of life for so many.”

Bill Carr’s name, when accompanied by his accomplishments, says all you have to know about the man: Lieutenant-General William Kier Carr, Distinguished Flying Cross, Venerable Order of Saint John, Commander of the Order of Military Merit, Legion of Merit, Member of Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame, First Commander of Air Command, Vice-President of Canadair and Bombardier and widely known as the “Father of the Modern Canadian Air Force”.

SACRIFICE — Flight Lieutenant Arnold Walter “Rosey” Roseland, 442 Squadron, RCAF

Of all the virtues in this list, sacrifice is likely the most distasteful to members of our modern Western society. It requires quite simply that we go without something or give up something. We are a society of not-in-my-backyard and me-first. We are a society that fights rather than shares. A society that bristles at the possibility that others want to share in our good fortune. Once we have everything we need, then we suggest that others might think about sacrificing—it should be OTHERS who take a pay cut, make concessions to keep a company in business, allow development in their community, cut emissions to save a planet, and who should stay in their war-damaged country. Sacrifice is a great concept, but it should be made by others, not us.

In the period of the Second World War, nearly everyone on the planet suffered in some way. Nearly everyone sacrificed something—gasoline for the car, food for the belly, and children for the war. The price was hunger, hard work, loneliness, sorrow, disability, disfigurement and even death. Everyone gave up something. Some gave up everything.

Those men and women who went to war suffered the most—years away from home, poor food, dangerous pursuits, mental health problems, injuries and death. Each of them was willing to sacrifice their futures for their community, their country and above all, their comrades. They knew the risks, of this there is no doubt. After a night raid, they could see the empty revetments at dispersal, see the mechanics hosing out a tail gunner’s turret, see the new crews standing bewildered, see the upside down beer mugs on the mantles, see their friends hospitalized with mental illness. They knew the risks, yet they still were willing to sacrifice all the remaining 25,000 or more beautiful mornings a young man might consider his due.

Arnold Roseland was a Canadian, born in a sod hut, the son of Norwegian immigrants in the middle of the last Great War in the middle of the sweeping cattle country of the Canadian prairies. Today, his birthplace Youngstown, Alberta, boasts a population of 170 souls. It was from small rural towns such as Youngstown that men like Arnold Roseland came to place their lives on the roulette table of war for, as the motto of his 442 Squadron said: One God, One King, One Heart.

“Rosey” was a young Kittyhawk fighter pilot with No. 14 Squadron, RCAF and then, when the unit became 442 Squadron, he flew Spitfires. His war was four years long and it took him across the country—Elementary Flying in Québec, Service Flying Training in Ottawa, staff flying in Trenton and McDonald, Manitoba, Kittyhawk flying in Ottawa, and then British Columbia—and the distant Aleutians fighting the Japanese and across the Atlantic to England and France on Spitfires, fighting the Nazis.

Sacrifice may not in fact be a virtue, it may be something unavoidable, something you have to do. But putting yourself in a place where the sacrifice required was death is a virtue akin to courage. All of Rosey’s squadron mates were making sacrifices, but Rosey had much more to lose than most of them, probably all of them. Most of the young men on squadrons during the Second World War were young unattached bachelors. Many may have had a sweetheart at home waiting for their return, but Rosey was married and had two young sons, one of whom he had barely even met. There is no doubt that after four years of flying and two of fighting, Arnold Roseland was weary, tired of the deprivation and longing to go home to his beautiful wife Audrey and to hold in his arms his new son, Ronald.

Of course, as you might imagine, Arnold did not get that chance. He died in a running gun battle high in the skies over a small French farming village called Saint Martin de Mailloc. His Spitfire was shot down and Roseland fought desperately to get out of it. According to those that watched on the ground, Rosey slid the canopy back and seemed to be steering the dying Spitfire away from a farmhouse. At the last second, he emerged from the cockpit and pulled the ripcord of his parachute while villagers watched in horror. The trailing chute caught in the Spitfire’s tail and Rosey followed his burning aircraft over the heads of the young French onlookers and straight into ground not ten metres from the farmhouse. The forward motion from the descent and crash catapulted the dying pilot over the wreckage in the manner of a trebuchet—a full 100 metres further, where his broken body collided with a thick fencepost snapping it in half. A small photo of Audrey was found in an adjacent field, as well as a brass Zippo lighter with the name “Roseland” engraved on it.

Arnold never got to hold his new son again, nor hug his firstborn or make love to his beautiful wife again. He never saw his hometown again, nor the heartbreakingly beautiful foothills of Alberta and those big skies that work their way into your soul. This was Arnold’s sacrifice, but the sacrificing did not end there. Audrey never saw him again, never saw her two boys playing with their war hero father in the backyard. Audrey would remarry and the boys had a strong father to help them grow up, but it wasn’t Rosey. He was lying in the now-liberated ground of the country he sacrificed his life to free.

So when you think you are sacrificing by eating out at restaurants two nights a week rather than three, or you are putting off getting a next generation iPhone until the one you have is a year old… you are not. You are just consuming at a reduced rate.

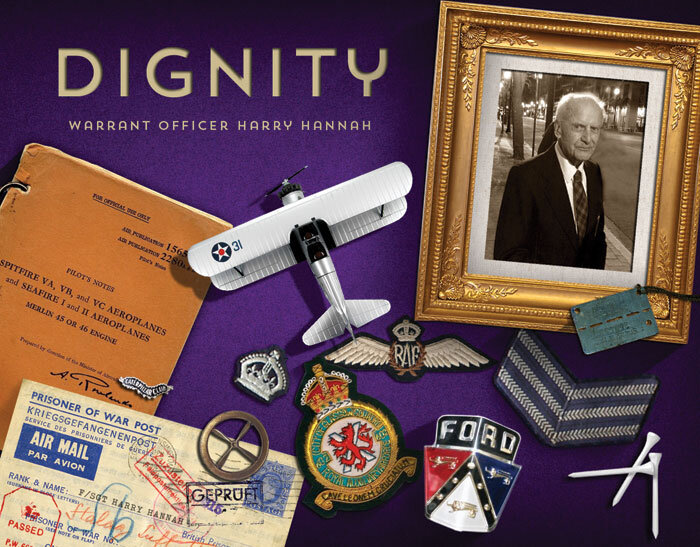

DIGNITY — Warrant Officer Harry Hannah, 602 Squadron, RAF—Glasgow’s Own

In the late winter of 1944–45, then Flight Sergeant Harry Hannah had been sitting, alone, with nothing to warm him but his thoughts, in a small, cold and damp solitary confinement prison cell in Poland for the worst part of a year. Before that, he had spent another year as a prisoner of war at Stalag Luft 4. It doesn’t take much of an imagination to figure out what he thought about to sustain himself through the long periods of abject loneliness—food, drink, friends, home, family, peace, flying, warmth, women, and a future that was quite possibly about to be taken away from him.

Harry could easily have been much changed by the near death experience when he was shot down, or the months in hospital and the long years of deprivation and imprisonment. He could have been a hard man, a bitter and unhappy human being. But he is most definitely not. Though enduring the loneliness and the deprivation was a terrible hardship, Harry would consider himself lucky that he was alive, for his fate, as he has described, could have been much worse at a number of turns in his flying life. One of the cannon shells that ripped apart his Spitfire’s engine on the coast of France in 1943 could just as easily have ripped apart his body. But it did not. When he tried to get out of his crippled Spitfire, the canopy jettison cable came free in his hand. He could just as easily have been trapped inside the dying Spit, but he managed to push the canopy back. He could just as easily have landed in the English Channel and drowned, but he did not. Instead he landed in the tidal mud flats of the Abbeville Canal and was captured. During the following year that he spent in solitary confinement, his subsequent liberation by Red Army soldiers and his dangerous overland and sea voyages of repatriation, Harry could have met a different and unhappy end. But he did not. He looked at everything with a positive mind and came through with inspiring dignity.

He was a Spitfire pilot flying for 602 City of Glasgow Squadron, one of the most vaunted and storied fighter squadrons of the Second World War. Some of the greatest and most highly decorated aces of the aerial war were also in the same ranks as Harry at 602 including Squadron Leader James Harry “Ginger” Lacey DFM & Bar, Free Frenchman Pierre Clostermann, Grand-Croix, Croix de Guerre, DFC and bar, DSC, Silver Star, and Air Medal, Wing Commander Brendan Eamonn Fergus “Paddy” Finucane, DSO, DFC & Two Bars, South African Johannes “Chris” le Roux, DFC and two bars, Air Vice Marshal Alexander Vallance Riddell “Sandy” Johnstone CB, DFC, AE, DL, and New Zealander Air Commodore Alan Christopher “Al” Deere, DSO, OBE, DFC & Bar.

Harry’s story equals any one of these great men, though he was not offered the accolades, gongs and gazetting heaped upon these heroic men. Harry’s story is one of survival, determination and heroism in the face of deprivation and malevolence. Harry’s story is one of dreams realized, of achievement unheralded, of greatness untold, of a life rejoined.

He carries himself with dignity and delight, humour and sartorial elegance. He is a man of few words, but great kindness. He is a man for men–imbued with humility, great sporting skill and a discerning eye for the ladies. He speaks highly of you if you deserve it and not at all about you if you don’t. He carries himself to this day with a back as straight as his 95 years will allow. He dresses like an aristocrat, speaks softly like a gentleman and smiles like a fighter pilot. No better man ever shook my hand.

Epilogue

FAITH — Hugh Thomas O’Malley, Farquhar Ship Chandlers

Although these stories on the Vintage News service are meant to be about aviation, aviators and the culture surrounding Canada’s considerable contributions to the history of aviation, I would be amiss if I left out another virtue which, in most cases it seems, sustained these men throughout the war, its deprivations and dangers—Faith. But the man who for me best embodied this key ingredient of a life of duty, sacrifice, courage, dignity, and humility was my father. He was not a fighter pilot nor was he even a veteran of the war. Before war broke out, my father finished high school in Halifax and went to Gaspé, along the southern banks of the St. Lawrence River, to work building gun emplacements and other facilities as war loomed. Following the outbreak of the war he enlisted in the Royal Canadian Navy, but failed the physical. Doctors detected a heart murmur. This, along with a slight congenital deformity known as pigeon chest, kept him out of the war. His heart condition did indeed kill him, but 73 years later after a very full life.

When, in later years, he spoke to me about his rejection from the Navy, I could feel his disappointment. Instead of navy service, he went to work for a ship chandler in Halifax, supplying the massive convoys of ships that were assembling in Bedford Basin—not with their cargoes, but with the supplies they needed to operate—fuel, oil, food, and maritime equipment.

Throughout the war and all through his life, Hugh found, in his God, the strength to make the sacrifices needed for his family, to remain dignified, to lead his family and to be a dutiful husband.

Portrait of his mentor. Wing Commander Adrian Warburton, DSO and bar, DFC and Two Bars, Bill Carr’s commanding officer at 683 Squadron. The son of a naval officer, Warburton was born in England, and christened on board a submarine in Grand Harbour, Valletta, Malta. Below his decorations (DSO, DFC and 2 bars), on his left breast pocket, Warburton wears “The Order of the Winged Boot”, an unofficial award given to airmen who had been shot down and forced to return to their base on foot or by other means. Warburton became one of the most successful and best-known aerial-reconnaissance pilots of the Second World War while flying sorties from Malta and North Africa in 1941–1943. Photo via the Imperial War Museum

He was both a simple man and a complex man. He asked for nothing, except good fortune for his family. He required little in the way of material things—nothing fancy to eat, to wear or drive. He did not hang out with the boys, play sports, drink or indulge in typically male pursuits. The metric of his success was calibrated not in possessions, but in the quality of his children and their children and their children. When he said Grace before a meal, it was both poetic and compassionate. When he joked it was definitely corny. When he was disappointed in you, you knew it.

As children, we saw him as a father figure in the uncomplicated mid-century sense—strong, compassionate, firm. He remained loving but always a father—a man of strength who took his role seriously. He had a career, but it was secondary to family life.

Despite his simple, outward persona, our father was perceptive, thoughtful, inquisitive, enamoured of God’s universe and capable of understanding complex and confounding theories. In the times he grew up, a young man who finished high school ceased to be a burden on his family and went out in the world to find a job and a bride and raise family. If he had been raised in the more privileged world he worked so hard to give his children, he would have been a scientist, a theologian, a philosopher, a quantum mechanic.

As it was, he was an armchair physicist. He loved creation for all it complexity and layered mystery—from the outer cosmic ripples of the expanding universe, to the reverse infinity of atoms, protons and quarks. He loved the complexities of the mind and convolutions of the brain. He was fascinated, some might say obsessed, by the existence of free will, and believed that its principles existed even in sub-atomic particles. He eschewed technology, but remained fascinated by its underlying science.

He was a deeply religious Catholic, a man of traditional but changing values, but his beautiful mind saw no conflicts with science, no threats to his faith. In fact, the more complexities of the universe that were revealed to him, the more his faith grew. In the cosmic dust of the universe he found affirmation of his profound Christian faith.

As any veteran of the Second World War will tell you, there are no atheists in a foxhole or the turret of a Lancaster. No one has ever thought of me as a religious man, but I understand and have witnessed that Faith is a virtue that sustains a person through tribulation. I have seen it in all the veterans I have known. For its unquestionable powers to keep people strong during adversity, to provide meaning in the face of tragedy and to sustain a soul in jeopardy of destruction, Faith is a virtue that we all must find. For me, and for now, I will put my faith in the strength of our heroes, armed forces, first responders, hard workers, volunteers, givers, team players and history makers—so many of whom hold faith in a God I have yet to find.

Happy New Year, and may good fortune find you this coming year. Dave O’Malley