THE LAST CARTHAGINIAN

It is our tradition at Vintage Wings of Canada to offer up a story of an American aviator on the occasion of Thanksgiving, that most important of American holidays. Of course, we have Thanksgiving in Canada as well, but it is a full month and a half before the American one, and truthfully, though it is important here, it does not hold the same emotional and patriotic power that it does for our friends to the south. For them it is an affirmation of the values they hold dearly to—family, freedom and hard work. Thanksgiving, the act, not the holiday, is at the very core of what we do at Vintage Wings and in the cyber-pages of Vintage News. Each time we take a young cadet flying, we are thanking our veterans. Each time the wings of our airplanes bite into the Canadian air, we are thanking our heroes. Each time we share their stories of duty, honour and sacrifice, we are thanking those young men and women who gave us our freedom. The greatest thanks we can offer up is to share their memory with future generations, that it may give them strength in all that they do, that it might inspire them to contribute to their communities and that it might give them understanding of the value of the freedoms they take for granted.

Here then is a story of an American who joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in the Second World War and who contributed greatly to its outcome; an American who first soloed an aircraft in the frigid Canadian winter not 50 miles from Ottawa and who finished his flying career with more than 20,000 hours without working for an airline. It is also the story of great courage and tragedy of an American who joined the RCAF, flew for the Royal Air Force and was accorded the lasting respect of the people of Denmark.

Bob Kirkpatrick was a friend of mine. We met at the end of his life. He lived 2,000 kilometres away from me and he was dying. We communicated over a period of not much more than 18 months. We spent barely 20 hours in each other’s company. When we parted, I cried. And so did he. I learned more about living a good life and dying a good death from this man, than any other man or woman in my time. To celebrate American Thanksgiving and my gratitude for having known this remarkable man, I would like to tell Bob’s story in three parts—three flights that he took in his 20,000 hour flying career. One is his first; one is his last and one is perhaps the most difficult and the most talked about—a low-level attack by Mosquito fighter bombers on the Gestapo’s Danish Headquarters in Copenhagen known as Operation CARTHAGE—five hours seared into Bob’s powerful memory.

The First Solo—St. Eugène, Ontario

The wind is driving down the valley this morning, with nothing to stop it all the way from Mattawa. The sun is shining in that cruel Canadian way, but it is bitterly cold. Colder than Bob Kirkpatrick has ever experienced. The air is hard. The snow is hard. The light is hard. The snow on the flight line of No. 13 Elementary Flying Training School is rolled, not plowed. The snow is so deep, the telephone poles look short.

Bob is in the front seat of a yellow Fleet Finch biplane. His instructor, Flight Sergeant Scott Smilie is in the back, speaking to him though the Gosport Tube. “It’s time.” he says, “You’re ready. Just remember… I am not in the back when you take off and she’ll fairly jump into the air. I’ll be waiting when you land. Three circuits, three landings.” Smilie slides back the rickety canopy, and crystals of ice, driven on the wind lash at Bob’s cheeks. He can’t see Smilie as he climbs out, but he can feel his firm hand on his shoulder, “Good luck”.

Leading Aircraftman Bob Kirkpatrick (left) and his much loved flying instructor Flight Sergeant Scot Smilie at No. 13 Elementary Flying School at St. Eugène, Ontario. Photo: Bob Kirkpatrick Collection

After the Second World War, St Eugène’s runways were used for motorsport racing up until the 1970s. Returned in the last decade to its original agricultural use, St. Eugène’s once busy runways are now faded from memory and from the landscape, visible only by satellite. Photo via Google Maps

His family and friends are far away, not even in the same country. The nice folks in the town of St Eugène, a kilometre to the north, speak French. He feels ready, excited, alone. The engine is warm after an hour of circuits, but his body is beginning to stiffen with the cold. With a heavily gloved hand, he pushes the throttle forward and taxies along the snow, the Finch’s metal covered wooden skis squeak and scrape on the surface, snow whipping in icy veils behind him. The little yellow airplane slides along behind three other Finches, yellow, stained with oil and patched. Sunbeams slant though their snowy wakes.

Soon Bob is alone at the threshold of the east to west runway as he slides around the corner, skis rattling on the ice. The wind is stiff and he can feel the Finch wobble and flutter, but the wind is straight down the runway today. He’s happy not to have a crosswind because the little biplane can’t handle much, but on skis, she’s harder still to control in an angled wind. He takes a deep breath, advances the throttle and the Finch gathers way. In seconds, he nudges the tail up and the Finch is dancing on the snowy ruts and surging into the wind. In seconds more, she lifts from the runway, and just like Smilie said, the little clattering airplane seems to leap into the air. Whether that is hyperbole or not, there is no exaggeration in saying that with it so leaps the heart of a young man. After only a couple of weeks, Bob has developed relaxed hands, easy feet and a sharp eye—the result of Flight Sergeant Smilie’s fine instruction and confidence building.

As he climbs, the smell of oil and exhaust permeates the cockpit, but instead of nauseating him as it does some of his fellow students, it invigorates him. Below him, the wide flat plain of the Ottawa Valley stretches to the horizon to the west and the south—snow, black leafless trees, and long blue shadows. The sun is so bright he can barely see it. His wings flick, his airplane bucks and dances, but already he knows there is nothing to worry about—his hand is silent on the stick, his grip relaxed, barely a grip at all. He lets the Finch frisk about his centred controls, a winged canoe on fast moving and invisible water. At 500 feet he levels her off, rolls his shoulders, stiff from a slight hunch in the cockpit. Bob is a tall man and the Finch is a small airplane—he wears it like a glove.

He knows he has to do three circuits, but for a few moments more he lets the Finch head to the west, just him and the lovely little airplane, alone. He lets out a whoop of ecstasy that only he and she will hear, lifts her right wing, holding the horizon still, and turns towards his future.

Related Stories

Click on image

The Last Carthaginian and the Shell House Raid

As 1944 drew to a close, the Danish Resistance movement, the Modstandsbevægelsen, was close to total collapse. The Gestapo (Geheime Staatspolizei) had arrested many of the key leaders of the movement along with a considerable collection of files and documents, which were in danger of compromising hundreds of operatives and the whole network of resistance, at a time when they could see the end coming for occupation. Both the prisoners and the documents were being held inside a building the size of a city block in downtown Copenhagen known as Shell House—the former corporate headquarters of Shell Oil in Denmark.

The leaders of the Danish resistance movement, deeply concerned about the information the Gestapo would get from the likely torture of their captured members or glean from the documents, repeatedly requested of the Royal Air Force a surgical bombing attack of the headquarters in an attempt to destroy the records and either release prisoners, or in a realistic understanding of the situation—to end their torture and inevitable execution. The RAF repeatedly turned down the Danish request, citing high risk of civilian casualties. Pressure and communication from Danish Resistance, however, won the day and on 21 March 1945, Operation Carthage was launched, a daring, high risk operation requiring 20 Mosquito fighter-bombers and 30 escorting P-51 Mustang fighters to fly low-level across the North Sea and Denmark, pick out one building amidst thousands and destroy it and the documents it contained... with the slim hope of freeing its inmates. The Mosquitos would make the surgical strike while the Mustangs would escort them in and suppress flak from the known anti-aircraft gun installations.

The Shellhuset (Danish for Shell House) in better times, before it was taken over by the Gestapo as their Danish headquarters and prison for captured Danes of the resistance. Photo via Danish Wikipedia

Shell House in the days before the attack, painted in dark green and black camouflage in a poor attempt to disguise the large structure. Photo via The People’s Mosquito

The Mosquitos, including those of Bob Kirkpatrick’s 21 Squadron, made their attack in three separate waves. The first wave of seven Mosquitos attacked from the west, led by lead navigator Squadron Leader Ted Sismore. One of the attacking Mossies in the first wave, flown by veteran pilot, Wing Commander Peter Kleboe, was so low that it struck a flood light tower in the rail marshalling yards. His Mosquito was thrown off course drastically, glanced off a rooftop and eventually crashed into a tree-lined boulevard next to a large school run by nuns, known as Institut Jeanne d’Arc, a Roman Catholic school on Frederiksberg Allé (Danish for Avenue). His immediate crash killed 12 civilians, fulfilling the great initial fear of the Royal Air Force’s planners. But it would get worse.

The first wave, other than the Mosquito of Kleboe, successfully found Shell House and hit the Gestapo Headquarters. The second wave, looking for Shell House, took the smoke from Kleboe’s crash to be evidence of a successful hit by the first wave on the target. Two of these six Mosquitos dropped their payloads on the French School, before realizing their error. Only one Mosquito from this wave managed to drop its bombs on Shell House.

So much of the success of the raid would be the result of training and superior navigation. The master navigator for the raid was Pilot Officer Ted Sismore (left), Lead Navigator for Kirkpatrick’s 21 Squadron and someone that Bob spoke of in reverent tones. Sismore was also lead navigator in other low-level raids such as Operation JERICHO and the Aarhus Gestapo Headquarters Raid. Like Bob Kirkpatrick and Wally Undrill, Sismore was part of a two man team. His pilot on most of his operations was Squadron Leader Reginald W. Reynolds (right). Wikipedia states: “Over the following 20 months [after they teamed up], the pair would see little rest and make some of the most daring targeted raids of the war, which came in retrospect to recognize Sismore as the RAF’s finest low-level navigator of World War II.” Photo: Imperial War Museum

A photograph taken from a camera in one of the Mosquitos shows the wide curving sweep of Hammerich Street at centre left and the rail lines leading into the city. Judging by the light smoke, this is from the PRU Mosquito that accompanied the first wave of six 21 Squadron Mossies. The smoke seen at the lower right comes from Shell House. The smoke in the mid-left is possibly from the flak guns located on the top of a building called the Dagmarhus. This flak position was known by planners prior to the raid. A wonderful interactive map of Copenhagen with details of the raid is available on line here. Photo: Nationalmuseet (National Museum of Denmark) Flickr page

A close-up of the previous photograph reveals a dramatic, if slightly retouched, image of an RAF Mosquito thundering over Copenhagen coming from the west, having just attacked Shell House. The buildings in the scene still exist today. Photo: Nationalmuseet (National Museum of Denmark) Flickr page

A screen capture from a pretty grainy RAF film shows Mosquitos making a turn across the rooftops of Copenhagen. All of the film shot for the RAF was shot from two camera ships including Bob Kirkpatrick’s Mosquito. His normal “looker” (RAF slang for navigator/observer), Wally Undrill, was replaced for this raid by an RAF cameraman named Sergeant Raymond Hearne. What we see here is what Bob saw. RAF film footage

The final wave, including the Mosquito flown by Flight Lieutenant Bob Kirkpatrick, was led by Wing Commander F.M. Denton. He too was confused by the smoke from Kleboe’s crash and the second wave’s mistake. All but one of the seven Mosquitos dropped their bombs on the school. Bob was the only one who did not, but this was because he carried incendiaries and it was planned that he be the last one in and drop his payload a few blocks beyond the target to create a diversion. His bombs fell relatively harmlessly about a kilometre from the intended Shell House target.

Bob’s prodigious memory recalled that day with utmost clarity in a post [edited] on a web forum:

“We flew MkVI Mossies, mostly at night and singly. On 15 March 1945, I was sent to Cambrai, France to pick up a Mk IV Mosquito (RAF serial DZ383), previously used by 2 Group for PRU (Photo/Recon) work. The aircraft was at 138 Wing [Special Operations Wing, RAF Tempsford—Ed] and on 16, 17 and 18 March, we flew some picture taking of low-level formation practice of 21 Squadron [Bob’s own squadron]. My “looker” (navigator) Fl/Lt R.S. Undrill took the pictures. On 20 March, an RAF photographer named Sgt Hearne went with me as we followed 21, 464, and 487 Squadrons to RAF Fersfield airfield [near Norwich].

It was early morning on the 21st that we were briefed at RAF Fersfield and told about Shellhaus.

There were 20 Mossies—my 21 Squadron had 6 in the first wave, plus Mosquito DZ 464 [another Mk IV flown by Fl/Lt Ken Greenwood]. 464 Squadron of the Royal Australian Air Force had six in the second wave and 487 Royal New Zealand Air Force had six plus me in DZ383 in the third wave. Low level all the way, Embry (our Commanding Officer) said “Anyone flying higher than me... I’ll personally shoot him down!” Don’t know how he would have known, he was third in first wave. At Lake Tissø, about 20 miles west of Copenhagen, the first wave went on, the rest were to circle Tissø once for 464 Squadron, twice for 487 Squadron and three times for me in DZ383 and then proceed to target.

As I was about two minutes from target, I saw four Mossies coming from my left and turning east towards a big pile of smoke and I thought to myself “Am I lost?” They have navigators and they were so close, I either had to turn right 360 or get close to them because of the delayed action bombs—30 seconds for first three aircraft of the wave, 11 seconds for the second three. I slipped right next to Number 4 and we went through the smoke and they unloaded their bombs. Unfortunately, as we later learned, on the Jeanne d’Arc French School. I was carrying incendiaries and told to drop them a few blocks from the target to create a diversion in case some of the prisoners were able to escape. Turns out, I burned up a few houses east of the school and west of Shellhaus. Our windscreens were fouled with salt spray and difficult to see through. This precluded my right 360 (when I found the four aircraft) and prompted me to join Number 4 from 487. As it turned out, 464 Squadron, the second wave, had also been diverted by the school crash and missed their run-in too. They orbited and the leader managed to bomb Shellhaus. Two were shot down and one took his bombs home. Good news, bad news; had 464 been successful in their orbit and 487 on target. Had everybody been on target, no prisoners would probably have survived.

A photograph taken by a Copenhagener (likely at great personal risk) shows just how low the attacking Mosquito bombers were as they sweep across the rooftops of city. The spire at left looks very much like that of the International Church of Copenhagen, which puts this photo a few blocks to the east of the Shell House and likely on the run out from the target. It would be shortly after this that the aircraft would have been in the sights of AAA guns aboard the German cruiser KMS Nürnberg tied up in the harbour. Mosquito (SZ977), flown by the 21 Squadron’s leader, Wing Commander Kleboe, struck a light tower at a bend in the rail yard. The damaged Mosquito was thrown dramatically off course to the left, where it grazed a building, shedding one of its bombs. It staggered through the air for another kilometre or so before crashing into The French School on Frederiksberg Allé. Unfortunately, the smoke coming from the crash at the school was interpreted by several following aircraft as the Shell House target. The results were tragic. Photo: Danish Public Domain

Another photograph taken by a Dane on the ground shows Mosquitos during the raid, inbound over the suburbs of Copenhagen. Bob said of this photo: “I think the four Mossies are the remnants of 487 Squadron making an orbit, the Mossie far right is probably FPU flown by myself. We were two minutes behind as planned but the orbit made me catch up to them. Things went to hell after that. I’m guessing at all this but the railroad towers, the spacing and the 4 Mossies are where I remember running into them. I went on East about a mile and they all took off to the North.” Photo: Danish Public Domain

We picked up some flak that damaged the starboard engine and the nose. Engine kept running OK but, as I wasn’t completely comfortable in the Mk IV Mosquito and it was a long trip, I was sweating fuel, eight fuel tanks to monitor, nobody to follow, I just flew reciprocals to my inbound course and when I saw England, picked the first field I saw to land. Turned out to be Rackheath.

There was no traffic at the time, about 14:00. Got the gear down but no brakes, so just coasted to a stop at the end of Runway 26. We were met by a jeep full of MPs and taken to the tower. Sergeant Hearne brought his film and when I called base and was told they would pick us up in the morning, he said “I’ll be in London before then.” I think he had asked an MP to take our picture which showed us examining holes in the cowling and nose. That was the last I saw of Mosquito DZ383 or Sergeant Hearne. I don’t remember much of my sojourn at Rackheath, probably slept most of the time.”

Bob Kirkpatrick and Ray Hearne at RAF Rackheath after the Shell House Raid: “This photo was taken after a precautionary landing at RAF Rackheath, a USAAC base, after returning from Copenhagen, March 19, 1945. Sgt. Hearne (right) FPU photographer was my passenger and the photographer on Operation Carthage. We were the 20th Mosquito in the op and 6 minutes behind the first flight. Flak was getting heavy and we were damaged in the nose and starboard engine. No navigator, so I flew home on reciprocals from the trip out doubling the drift. Without a navigator and no radio I landed at the first place I saw.” Photo via Bob Kirkpatrick

By the time the last Mosquito (likely Kirkpatrick’s) landed back on English soil, the Gestapo’s stranglehold on the Danish resistance movement has been released. The RAF historical website states “A reconnaissance aircraft of No. 34 Wing took off the following day and photographed the area. Interception reports of these photographs showed that the target had received severe damage. The top storey and roof of the south front were destroyed and the remainder was partially gutted and destroyed. The west wing was destroyed nearly to ground level and the east wing, the top storey and roof were destroyed and the floor below damaged. Rescue work was in progress when the photographs were taken. A photograph received later from Underground sources shows the building ablaze from end to end—concrete evidence the mission was most successful.”

The raid had succeeded in destroying Gestapo headquarters and records, severely disrupting Gestapo operations in Denmark, as well as allowing the escape of 18 prisoners of the Gestapo. Fifty-five German soldiers, 47 Danish employees of the Gestapo, and eight prisoners died in the headquarters building. Four Mosquito bombers and two Mustang fighters were lost, and nine airmen died on the Allied side.

Despite the better-than-expected success of the raid, the raiders were shocked and forever saddened by the damaged caused by the mistaken attack on the site of Kleboe’s crash. 86 school children died in the school along with 18 adults, most of whom were nuns. Though all these brave men would forever feel the guilt that went with that day, they all understood that war included these sorts of things, despite the planning and excellent execution. The reason that the Royal Air Force was so reluctant to carry out the raid in the first place was exactly because they feared the high possibility of civilian casualties. In the end, it was the pressure from the Danes that brought about the attack, and the Danish people would honour the surviving participants after the war.

Of the 50 pilots, 18 navigators and 2 photographer/cinematographers involved in Operation CARTHAGE, Flight Lieutenant Bob Kirkpatrick would live the longest. He returned to Copenhagen in 1993 and 1995 for the unveiling of memorials to the raid and the tragedy at l’Institut Jeanne d’Arc. He died this year on 2 February 2014. He was indeed the Last Carthaginian.

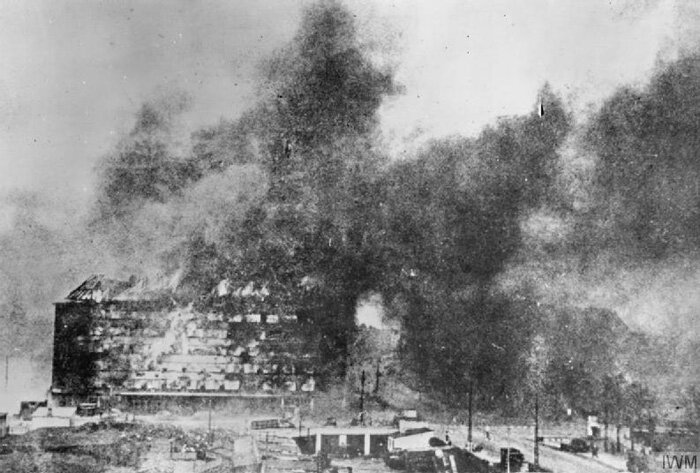

The destruction of Shell House as photographed by Danes on the ground

The northwest corner (back side) of Shell House collapses into the Nyropsgade (Nyrop Street) as flames begin to engulf the entire structure. Photo: Danish Public Domain

A close-up of the north face of Shell House at corner of Kampmann Street and Nyrop Street supposedly shows two men attempting to escape, one climbing down from a third floor window on Kampmann Street and the other contemplating a jump from the fifth floor. Some Danes managed an escape while others were seriously injured and even killed jumping. The Danish website Denstoredanske.dk describes the escape attempts: “Several Danish prisoners escaped from the bombed building with their lives, including two members of the Frihedsradet (Freedom Council), Mogens Fog and Aage Schoch. Four prisoners were trapped on the fifth floor, including Conservative politician Poul Sørensen and resistance man Carl Wedell-Wedellsborg. They found German military belts and, as Poul Sørensen recounted later, Wedell-Wedellsborg attached two belts to the steel windows and swung himself to the outside of the building and came back in on the fourth floor. Here he stood and pulled us in as we came down using the belts. From the fourth floor, four prisoners were forced to jump, with two dying from the fall including Wedell-Wedellsborg. Poul Sørensen survived with serious injuries.” Others have said that this photo was faked. It’s hard to tell. Photo via Denstoredanske.dk

Looking from the west later on in the day, we see the Kampmann Street facade of Shell House fully engulfed in flames. It appears that no great attempts were made to fight the fire as there is little in the way of firefighting equipment and hoses. It’s likely that the Gestapo would not let anyone near the building. Photo: Danish Public Domain

A short time later, the fire on the Kampmann Street side of Shell House reaches its peak. Despite the conflagration the facade did not collapse. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The south facade or front of Shell House on Vester Farimags Street at the peak of the fire. It was on these top floors that the Danish resistance prisoners were held by the Gestapo as a deterrent to attack from the air. The Danish resistance knew all too well that these men were being tortured and that none would be allowed to live anyway. The attack was called down by the Danish resistance movement to do two things: Prevent further information from being beaten from the prisoners and to help some escape or to end their suffering. Photo: Danish Public Domain

A Copenhagener watches from the southwest across Hammerich Street as the Shell House burns furiously after the raid. The facade in flames is that on Kampmann Street. Palls from two major fires darkened the sky above the beautiful city this day—at Shell House and at the French School on Frederiksberg Allé. Photo: Nationalmuseet (National Museum of Denmark) Flickr page

Looking at the main entrance to Shell House after the raid, we see there is nothing left to save. From this perspective, the raid was a total success. The sad and tragic result of the crash of Wing Commander Kleboe’s Mosquito would forever hang a pall over the daring raid, but this is part of history and must be told with the whole story. Photo: Danish Public Domain

The north facade of Shell House suffered the greatest damage with near total collapse. This image appears to have been taken within days of the raid as the ruins appear to still be smoldering. Photo: Danish Public Domain

The north facade of Shell House after the fire as cleanup begins. Much of the facade to the right was brought down shortly afterwards. Photo: Danish Public Domain

A similar photograph to the previous shot shows the same angle weeks later after the debris has been removed from the streets and the eastern part of the facade was brought down. We can see through the block to the inside of the front facade of Shell House. Photo: Danish Public Domain via denfrie.blogpsot.ca

A rare colour photograph of Shell House taken long after the attack showing the devastating effects of the raid. A Danish flag waves defiantly at right. Wikipedia sums up the results of the Shell House attack: “The raid had succeeded in destroying Gestapo headquarters and records, severely disrupting Gestapo operations in Denmark, as well as allowing the escape of 18 prisoners of the Gestapo. Fifty-five German soldiers, 47 Danish employees of the Gestapo, and eight prisoners died in the headquarters building. Four Mosquito bombers and two Mustang fighters were lost, and nine airmen died on the Allied side.” Sadly, the scoreboard must include the devastating crash and subsequent mistaken bombing at the French School on tree-lined Frederiksberg Allé. Photo: Danish Public Domain

Institut Jeanne d’Arc—the Terrible Price

Institut Jeanne d’Arc, a Roman Catholic school on Frederiksberg Allé, Copenhagen, established in 1924. It was struck by a crashing de Havilland Mosquito 1.5 kilometres to the northwest of the actual target. Though this caused destruction, the smoke and flame from the crash attracted incoming Mosquito fighter bombers of the second and third waves. As many as 7–8 of these crews mistook the site as Shell House and released their bombs on the school. Photo by Stender, via Royal Library, Copenhagen

In this poor resolution photograph of firefighters attempting to put out fires in buildings adjacent to l’Institut Jeanne d’Arc on Maglekildevej, we can see the form of the vertical stabilizer (with fabric covering of the rudder burned away) from Wing Commander Kleboe’s Mosquito rising from the smoking ruin. Kleboe and his navigator F/O Reginald J.W. Hall were killed instantly. The firefighters who attended the disaster reported that the damage was extensive not just to the buildings but to the water system causing reduced pressure in the lines, as witnessed by the ineffective water flow in this image. Photo via Flensted.eu.com

Fires rage at the site of the crash of Kleboe’s Mosquito and the subsequent mistaken bombing. Photo: Nationalmuseet (National Museum of Denmark) Flickr page

Another dramatic image of the chaotic scene at the French School. Photo: Nationalmuseet (National Museum of Denmark) Flickr page

In the neighbourhood of Frederiksberg, firefighters struggle to keep control of the fire at the French School. Photo: Danish Public Domain

Today, a memorial of heartbreak stands at the site of the destruction of the Institut Jeanne d’Arc French School. Two children look with fear to the skies, while a teacher/nun comforts them. Pilots and planners of the raid, while successful in their goal, would have to live with the knowledge of the accident that took so many children’s lives. The catastrophe would claim the lives of 18 adults and 86 schoolchildren, one of the most tragic events in Copenhagen during the Second World War. Bob Kirkpatrick would follow a flight of Mosquitos mistakenly attacking the site of the crash. He carried only incendiary bombs and was instructed to drop them a few blocks past the aiming point to create a diversion in the event that prisoners were attempting to escape. He would fly right through the smoke at Frederiksberg and release his incendiaries a kilometre from the intended target to the east. Photo: Danish Public Domain

A memorial at the entrance to the modern building that was built on the site of Shell House after the war lists the eight Danish resistance men who were killed in the attack. Photo via Wikipedia

The Last Flight of the Last Carthaginian

When Bob died this past February, he was just 12 days short of his 92nd birthday. Truthfully, you could not ask much more of a man from a generation whose life expectancy was much shorter than men and women can expect to live today. On top of that, he lived a very good life. A full life. He married beautiful Ginny, his high school sweetheart, and continued on flying right into his 80s. He was not afraid of work or risk. He made a point of enjoying the moment and of setting aside time every year to leave behind work and truly savour the things he loved the most—his bride, his family, fishing, dogs and yes, flying. Two Thanksgivings ago, I was in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, sharing Thanksgiving with another good friend and his family. I was still emailing Bob every day to see how he was and trying to regale him with stories of my Thanksgiving, when Bob replied by email... “Put down that computer, and go enjoy yourself and your friends.” I took his advice.

The year after I first met Bob, we met at the Mosquito Memories event at the Hamilton International Air Show. For the amazing story of how Bob managed, in his 91st year, to get there, click here. Photo: Peter Handley

On the evening of 2 February 2014, I received this email from Bob’s gracious and loving neighbours, Deb and Dave Dodgen, who had the previous year driven Bob and Ginny to the Hamilton International Air Show: “It is with a heavy heart we inform you that our good and dear friend Bob Kirkpatrick died this afternoon. He was failing rather quickly the last couple days and went to the hospital yesterday. His prayers were answered and it is now blue skies for Bob. Over the last few months, we talked often about all his friends. He always said how grateful he was for his long life and the many friends he and Ginny made along the way. We are so fortunate to have been included in that circle of friends.”

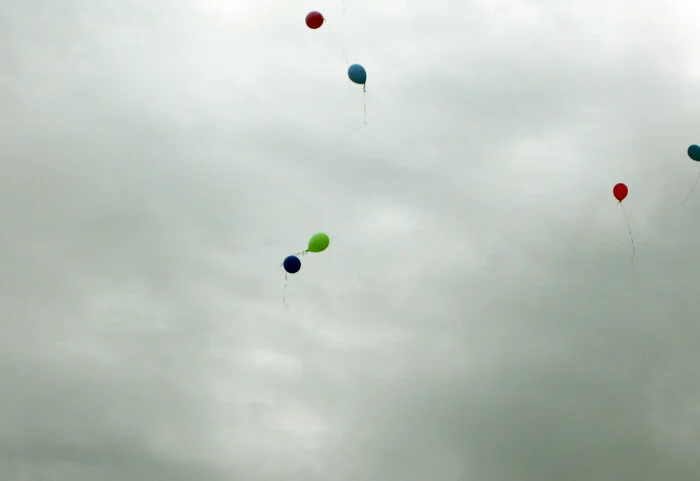

Despite the long and beautiful life he had led, I sighed deeply and quietly wept for Bob, for I too was fortunate to have been included in that circle of friends. The memorial service was small and for immediate family only. But later, in the summer, the family had plans to take some of Kirk’s ashes aloft and let them fall where they may.

And so it came to pass that on Sunday, 22 June 2014, family members and beloved neighbours Dave and Deborah Dodgen gathered at the Humboldt Municipal Airport after a brunch to celebrate Bob’s life. All day the ceiling had been low, with gloomy skies and in the end they cleared enough to allow Dave Dodgen to take his Beech Bonanza to 5,000 feet. Bob’s request had been to drop his ashes from 10,000, but like any experienced aviator, he would have understood that weather does not always cooperate with the plan.

Moments before Dave takes Bob on his last ride, the family offers up a toast (with Dave quaffing his Merlot only when he returned from the flight). Left to right: Deb Dodgen, Dave Dodgen, John Kirkpatrick (Bob’s son), Klayton Kirkpatrick (grandson), Ginny, Andrew Schatz (grandson-in-law), Krystal Schatz (granddaughter), and Barb Kirkpatrick (daughter). Absent that day but there in spirit were Mary and Gail Wetzel (daughter and husband).

Prior to taking him on his last flight, the family made several toasts to Bob, and I was honoured that one I had emailed to the family was offered up before the flight: “Here’s to Kirk, a man who lived life as if every day was his first—with open eyes and open heart. Here’s to his love of flight, his love of fishing, his love of friends, his love of Iowa and above all his love of Ginny. Bob reached out to me in his 90th year and changed me for the rest of my years. He showed me courage in the face of adversity. He demonstrated through his actions that adventure was not just the purview of younger men. I see him now standing to take the applause of the hundreds in attendance at the Mosquito Memories event. Tears of pride come to me as I write this, but they are also tears of joy for a man who lived his life well and gave so much. I thank him from all of his friends here in the Royal Canadian Air Force for his service and his valour.

I see him again now—in the pilot’s seat of a beautiful Mosquito Fighter-bomber, flashing at high speed at low-level across the North Sea towards England, towards home. His hands are calm upon the yoke. His face reveals no stress at all in the setting sunlight. There is even a hint of a smile. There he will remain in my heart, happy, courageous, competent, self-aware... eternally heading home to Ginny.

Here’s to Kirk.”

On his way to spread Bob Kirkpatrick’s ashes, Dave Dodgen taxies his Beech Bonanza out to Runway 12/30 at Humboldt Municipal Airport, a runway used many times by Bob Kirkpatrick. Photo via Dave and Deb Dodgen

While Bob’s son John takes the controls, Dave sends Bob’s last mortal remains down the funnel, though the hose and out into the slipstream, that place where Bob spent so much of his beautiful life. Photo via Deb and Dave Dodgen

Half an hour later, while the women watched from a park along the shore of the West Fork of the Des Moines River, Dave and Bob’s son John, his grandson Klayton and his grandson-in-law Andrew circled above with Bob. At 5,000 feet, Dave handed over control of the Bonanza to John Kirkpatrick, slid back the vent on the left side window, and extended a small hose out into the slipstream and in a just a few moments, Bob Kirkpatrick’s ashes were drawn into the slipstream of history. The cloud of his ashes likely could not be seen on the ground, but they spread out across the humid sky, lingering there, as if wishing to live as Bob had done—aloft and free. Some would come down in the cornfields of Iowa, drawn into the very soil of the country Bob Kirkpatrick loved so well. To join the spirit of America. To be part of its future.

Some of this tiny cloud would come down in the slow moving muddy water of the Des Moines River, drifting on its current, his spirit winding its way through oxbows, past cattle farms, endless corn and soy fields and industrial centres, tumbling in the rotors and eddies. Inexorably, but with certainty, these molecules of that great man joined the South Fork of the Des Moines and then eventually the Mississippi River itself, the storied femoral artery of America. Bob’s life, his love, and his memory has now joined the very lifeblood of the United States of America, coursing its way towards the Gulf of Mexico.

Here’s to you Bob.

Dave

The cloud of ashes would disappear on the wind and settle much later across the Midwestern plain, working their way into the soil that Bob loved so much. Some would land in the slow moving water of the West Fork of the Des Moines River, where it would travel to the fork, join with the main Des Moines River 5 miles south, then south to the mighty Mississippi. There is no doubt that some of Bob lies in the Gulf of Mexico, a place where he loved so much to visit and fish. We can just make out the threshold of the Humboldt runway at centre left. Photo via Deb and Dave Dodgen

At 5,000 feet Dave Dodgen circles the beautiful Midwestern farming community of Humboldt, Iowa on the great, green plain of America—and the final home (of more than 26 separate homes) in their married lives for Ginny and Bob. Humboldt, as any American town, is hometown to many notable citizens, perhaps the most famous of which is 60 Minutes’ Harry Reasoner. The airport can be seen at centre left along the banks of the West Fork of the Des Moines River. The little town of Humboldt was named after Alexander von Humboldt, Prussian naturalist, geographer and explorer, the namesake of the Humboldt Current, Humboldt Penguin and the Humboldt Squid and for whom eight towns are named in the USA alone—in Iowa, Illinois, South Dakota, Nebraska, Tennessee, Kansas, Minnesota and Arizona—and one in Saskatchewan, Canada. Photo via Dave and Deb Dodgen

Members of the family release balloons for Bob. Signifying his love of flight, they float skyward as his ashes settle to the earth he loved equally well. Photo via Dave and Deb Dodgen

Down by the North Fork of the Des Moines River, Bob’s wife Ginny and Deb Dodgen raise a glass on the occasion of Bob’s last flight—more than 20,000 hours since he first soloed at St. Eugène airfield in the dead of a Canadian winter in 1942. Photo via Dave and Deb Dodgen

For pilot Dave Dodgen, Bob and Ginny’s neighbour, it was an honour to fly Flight Lieutenant Robert “Kirk” Kirkpatrick, RCAF on his final flight, but it was emotionally draining. Here he rests in his hangar with his dog after the flight, with the late evening light streaming in. In honour of the last flight of a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force, Dave wears his RCAF t-shirt and a Vintage Wings of Canada ball cap. Though he was an American, he was very proud of the fact that he was born in Manitoba whilst his family was visiting there, and prouder still, much prouder, of his service with the Royal Canadian Air Force. Photo via Deb and Dave Dodgen

This is how I want to remember Bob—looking skyward, pain gone from his face, remembering his comrades, proud, living life to the last drop, free. Photo: Richard Mallory Allnutt

![So much of the success of the raid would be the result of training and superior navigation. The master navigator for the raid was Pilot Officer Ted Sismore (left), Lead Navigator for Kirkpatrick’s 21 Squadron and someone that Bob spoke of in reverent tones. Sismore was also lead navigator in other low-level raids such as Operation JERICHO and the Aarhus Gestapo Headquarters Raid. Like Bob Kirkpatrick and Wally Undrill, Sismore was part of a two man team. His pilot on most of his operations was Squadron Leader Reginald W. Reynolds (right). Wikipedia states: “Over the following 20 months [after they teamed up], the pair would see little rest and make some of the most daring targeted raids of the war, which came in retrospect to recognize Sismore as the RAF’s finest low-level navigator of World War II.” Photo: Imperial War Museum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1628195029051-0LADC4MUFT9PUWLNY8B4/ShellHouse39.jpeg)