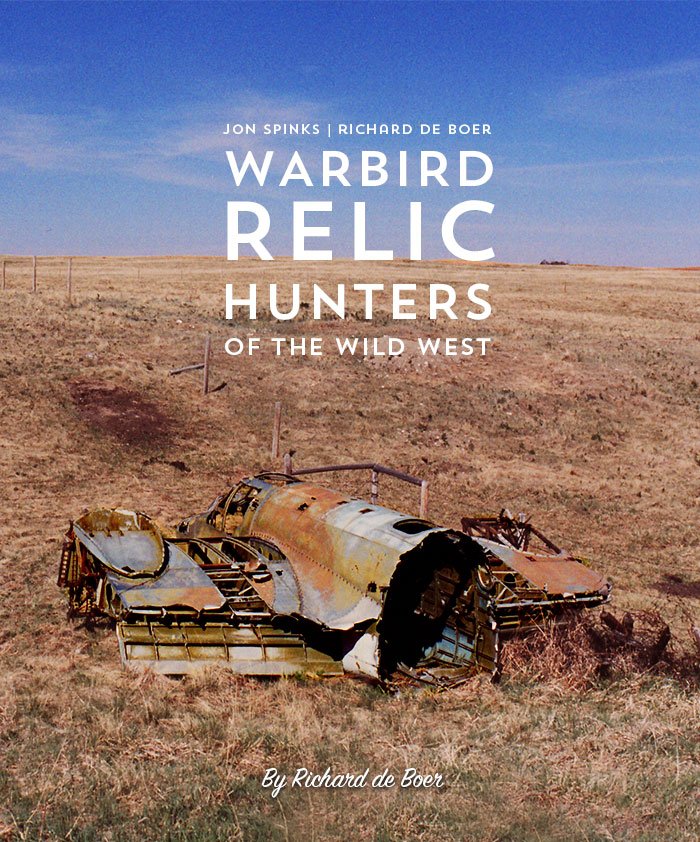

Warbird Relic Hunters of the Wild West

As the Second World War came to a close, thousands of war-surplus combat and training aircraft were stored at storage, repair or disposal facilities across Canada. British Commonwealth Air Training Plan Airfields began to fill up with the discarded implements of war—Avro Ansons and Lancasters, Bristol Bolingbrokes, Airspeed Oxfords, de Havilland Tiger Moths, Fairchild Cornells, and more. Most were sold for scrap, some were burned, some bulldozed, but many were sold to local farmers who recognized the old flying warhorses for what they had become—machine parts on the hoof. Not long after the war, they arrived with their tractors and flatbeds at auctions and, for a couple of hundred bucks, carted off or even dragged away across the fields the once-mighty implements of air power. Over the blazing summers and hard winters that followed, they were cut up, pulled apart, drained of their life blood, and cannibalized for components that were now more valuable to farm work than to war craft. Over the years they began to disappear, to rot and to be subsumed into the ground they fought to keep free. Lying out in the prairie sun, the remnant warbirds awaited their final demise. Then, a few decades after the war, there appeared on the horizon a few young men who were brought up on stories of courage, duty and aviation by parents who had lived it just a few decades before. Like high plains drifters, they rode across the prairie in pickups, tracking down the bones and desiccated carcasses of these once-great birds. This is the story of two of those riders of the planes—Jon Spinks and Richard de Boer. Along with others who saw the historic value of what others saw as junk, they played a major part in bringing historic aircraft back to life.—Ed.

Warbird Relic Hunters of the Wild West

When Mosquito KA114 flew for the first time after its restoration in 2012, warbird enthusiasts worldwide celebrated, for it had been 16 long years since the sight and sound of a flying de Havilland Mosquito had graced the sky anywhere on the planet. I smiled as well, but perhaps for reasons more than most, as I had a strong personal connection to this particular Mosquito. Recently, I was reminded of that connection when a member of the Mosquito restoration crew at the Canadian Historical Aircraft Association in Windsor, Ontario asked me whether the main wheels and brakes which they had acquired from Calgary many years ago had been overhauled and were serviceable. I was slightly taken aback to discover that no one there seemed quite sure how they had acquired their main wheels, or from whom. I promised them to fill in the blanks and to provide them with the provenance on their parts.

In 2012, warbird lovers around the globe delighted in the first and subsequent post-restoration flights of de Havilland Mosquito KA114, one of 338 Mk XVI Mossies built in Canada. Prior to these flights, the last flight of a Mosquito anywhere ended in tragedy when it crashed during a demonstration in England in 1996. Photo: Gavin Conroy

Between 1985 and 1995, I spent a lot of time with a good friend scouring the farmyards of Western Canada looking for the military airplanes that were made surplus after the Second World War. It started when my friend Jon Spinks was a child back in England, reading airplane books and magazines as many of us did. He read about all the airplanes sold as surplus in Canada after the war, never thinking that they would become a big part of his life until one day, when he was fourteen years old, his parents decided to move to Southern Alberta.

Once he and the family settled into the prairie city of Lethbridge, Jon’s father took him on a fishing trip. Heading out for a day trip, they passed a sign pointing to the hamlet of Pearce, Alberta, which, to Jon, had a very familiar ring to it. He remembered reading that, after the war, many Lancasters had been stored there. He begged his understanding father to make a detour so he could walk the hallowed ground and perhaps see if there were any Lancs still left on the property. This was the early 1980s and of course by then the airplanes were long gone. Though the airplanes were gone, the old airfield proved a fertile hunting ground for a young teen with old airplane stars in his eyes, as lots of Lancaster parts still littered the fields. From that day, Jon was hooked.

Jon progressed to checking the local scrap yards and tracking the sales of surplussed wartime airplanes. His big dream was to find one of the Lancasters spared from the scrappers torch and restore it to flying condition. Long before there was a Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, Alberta, Jon discovered the rapidly deteriorating roadside attraction Lancaster sitting at the north end of that farming town, and generously offered to take it off their hands and fix it up for them [he was declined of course]. Jon also talked to 408 Squadron RCAF at Canadian Forces Base Namao about their significant collection of Lanc parts. He was serious and he was determined.

I first met Jon in the early 1980s when he convinced his father to drive him to Calgary to see the Lancaster there. At the time, I was working for the new Aerospace Museum and the Lancaster was still outdoors sitting on its concrete pylon. Jon asked if he could see it up close, so we went over with a ladder and a key so that he could get the inside tour. It was inside the Lancaster that I got my first taste of Jon’s rapid-fire interrogation technique designed to squeeze from the subject every crumb of knowledge about which he so passionately wanted to know.

“What is the plan for the airplane?”

“When are you going to take it down?”

“Is the spar damaged?”

“How much time is on the engines?”

“Could it be flown?”

“What would it cost?”

“How would you paint it?”

Bam, bam, bam! It felt like a long series of rapid-fire punches to the brain. In successive years, I sympathized with many a farmer who found himself on the receiving end of such a grilling.

Jon (right) interrogates a Saskatchewan farmer about the war surplus airplane he bought and what he did with all the parts he had removed from it. Farmers purchased the aircraft for the various components that could be repurposed for farm work—fuel tanks, Perspex panels, aluminum skin panels, residual oil, glycol and even fuel. Here they inspect a hydraulic ram (grey cylinder) from a Bolingbroke’s landing gear which has been reused in a home-made hay loader. Family farmers operators across Canada nearly all had basic welding and metal-fabrication skills along with an arc welder in their implement sheds. They knew a good and cost-effective source of usable parts when they saw one and a complex all-metal aircraft like a Bolingbroke was seen as a treasure trove. Photo: Richard de Boer

Related Stories

Click on image

Over the next couple of years, Jon came to learn and finally accept that there were no wild Lancasters left roaming the Canadian Prairies. Not to be deterred, he set his sights on the next best thing: a Bristol Fairchild Bolingbroke—a twin-engine patrol and bombing and gunnery training aircraft (a Canadian-built variant of the Bristol Blenheim Mk IV) used by the RCAF in the Second World War. With more than 600 built for Canadian service, it turned out there were still some of them on farms across Canada, and a growing interest in the type in the United Kingdom with one British organization serious about restoring one to flying condition. Jon managed to find, disassemble and salvage his first “Boly”. He located a second example and asked me if I would like to help him recover it. It was the start of a ten-year long adventure for both of us.

The Canadian-built Bristol Bolingbroke was a variant of the ubiquitous Bristol Blenheim and was manufactured by Fairchild Aircraft in Longueuil near Montréal, Québec—626 were constructed for use as a maritime patrol aircraft and a bombing and gunnery training platform. This particular all-yellow Boly served at No. 8 Bombing and Gunnery School in Lethbridge, Alberta during the war and then was stored pending disposal at No. 1 Reserve Equipment Maintenance Unit (also at Lethbridge). It survived the war and was bought by a farmer by the name of R. Yancie in Legend, Alberta (east of Lethbridge). Today, the remains of 9896 can be found at the Canadian Museum of Flight in Surrey, British Columbia. Photo: RCAF

Abandoned and rotting on the Alberta Prairie in 1988 is Bristol Fairchild Bolingbroke IV, (RCAF serial 9041), the world’s oldest surviving example of the type. Most of the “Bolies” found on the prairie came from surplus centres near the training bases they once operated from. As a result, most were painted in the standard overall yellow paint of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. This was the author’s first experience rescuing a large component aircraft in the “wild”. The state of this aircraft belies its great history. After being taken on strength by the RCAF on 1 October 1941, it was delivered to No. 8 Bombing Reconnaissance Squadron at RCAF Station Sydney, Nova Scotia. By January of 1942, it was flown across Canada to patrol the West Coast, based from RCAF Station Sea Island (now the site of Vancouver International). On the day it arrived there (12 January), it collided with a Kittyhawk while taxiing on the ground. With only 105 hours on the airframe, it went to Boeing Aircraft of Canada (occupying a facility at the same Sea Island airfield) for repairs, finally leaving there at the end of July 1943. It remained at Sea Island as a patrol aircraft and added another 200 hours on the airframe until the end of November 1943. It never really saw service again after that, being stored pending call up by No. 4 Training Command (based in Regina) and then No. 2 Training Command (based in Winnipeg). It was put up for disposal and stored at No. 10 Repair Depot in Calgary. It was sold to a farmer named John Hutchison near Cochrane, a few miles northeast of Calgary, who in turn sold it to Jon Spinks and Richard de Boer in 1988. The hulk and assorted parts made it to the Nanton Lancaster Society (operators of the Bomber Command Museum of Canada). The forward fuselage, which had been partially restored and put on display at Nanton’s museum, was offered to the tiny Manx Military Aviation Museum on the Isle of Mann. Her wings and other components are still stored at the BCMC’s storage facility. Photo: Richard de Boer

Every summer for a decade, we would acquire a truck, and if necessary a trailer, and head out to track down the elusive war surplus Bolingbrokes that Jon had researched over the winter. We had some great adventures, met some very cool people and did some interesting deals with museums, dealers, restorers and collectors in Canada, the UK and the USA. We split the expenses on our salvage trips and co-owned anything we found. We financed some of the trips by selling any non-Bolingbroke things we came across: bomb racks, war time RCAF neck ties, flying boots, a P-51 header tank, Lysander canopy and wheel pants, a P-40 radio, etc.

Jon Spinks poses with a 42-foot-long Bolingbroke fuselage on a 24’ trailer at a rest stop in eastern Saskatchewan in the summer of 1994. This one was sold out of Macdonald, Manitoba on the shores of Lake Manitoba having been recovered from north of Dauphin, Manitoba. During the Second World War, Macdonald was home to No. 3 Bombing and Gunnery School while No. 10 Service Flying Training School operated at Dauphin. On this particular recovery, de Boer and Spinks were accompanied by legendary aircraft restorer John Romain of the Aircraft Restoration Company at Duxford. The old air base at Macdonald was, by that time, a Hutterite Colony, a communal branch of the Anabaptists, similar to Amish or Mennonites. Arriving with a bomber on a trailer drew plenty of attention from the pragmatic and social Hutterites. Photo: Richard de Boer

Recovering one of several Bolingbrokes with Jon Spinks, the author is poised triumphantly on the front-end loader. This particular aircraft was made surplus at a sale in Swift Current, Saskatchewan and was found on a farm 30 km southeast of that city. Photo via the author

Inside any pilot or warbird collector hides the young boy or girl who first fell in love with flight and history. Here we see author Richard de Boer (probably making airplane noises at that moment) in his Aladdin’s Cave of Warbird Wonders (also called the family garage) and seated behind a P-51 Mustang windscreen with control stick (New Old Stock – NOS) in his hands. We can also see Mosquito fuel tanks to the left and engine cowling on the wall behind (with opening for Merlin exhausts). At the back is also a Lancaster rear gun turret along with his daughter’s stroller. Photo: Richard de Boer

Another view of de Boer’s garage. In the foreground stands a very rare Armstrong Whitworth gun turret from an Avro Anson Mk. I. To the right is a collection of NOS P-51 parts: magnetos, starters, torque tube, ammo boxes, hydraulic rams, etc. “Selling any Mustang part was always a one call deal and you had your choice of buyers”, says de Boer. Photo: Richard de Boer

Like a trophy bass, warbird relic hunter Jon Spinks proudly hoists a P-51 Mustang header tank he has just pulled from the bottom of a non-aircraft metal scrap heap near Westbourne, Manitoba. Jon had a diviner’s gift when it came to locating old airplane parts. Selling non-Boly parts like this tank helped to finance the two men’s trips. The buyer of this treasure would later send them a single $1,000 bill in the mail. Photo: Richard de Boer

After we had salvaged several Bolingbrokes, Jon identified the one that he wanted to restore. In order to attain full ownership of it, Jon offered to trade me some other parts to buy out my half. I agreed in principle and soon thereafter he showed up with a small pickup truck loaded with de Havilland Mosquito parts. Done deal! Where the Lancaster was his dream airplane, the Mosquito was mine.

Jon explained that a Mosquito had been sold surplus out of Vulcan, Alberta at the end of the war. It was bought by Farmer Smith for $150, who in turn sold it to a local teenager who had spotted it rotting away in his yard twenty-five years later. The then 18-year-old Clint Armstrong paid the same $150 for the sagging airframe in 1973, and with the help of his father and friend Randy Umsheid, had dragged it home to Champion, Alberta where it sat for another five years. (See the home movie shot by Clint’s father Floyd on moving day: https://youtu.be/t10w39bMY7o)

In 1978, Ed Zalesky, who was at the time the director of the Canadian Museum of Flight and Transportation in White Rock, British Columbia, heard about the airplane and bought the sad and sagging remains of the Mosquito for exactly what Clint and Farmer Smith had paid for it years earlier: $150. Modern mythology and books on Mosquito survivors record that the Zalesky crew took a break from loading the airframe only to come back to the fuselage broken in two by an overeager farmer. Don’t believe that part of the story. Eventually Zalesky, not one to maintain the $150 tradition, sold the Mosquito to Jerry Yagen for $25,000 US. Many years and a couple of million dollars later, KA114 was resurrected and flown again in 2012.

But back in 1992, my friend Jon did what, to date, no one else had done: he traced back the airplane to its first postwar owner, Farmer Smith, and subjected the poor man to an infamous Spinks grilling.

‘What did you take off the airplane?

Where did you use it?

Do you still have it?

Did you trade any of it away?’

Farmer Smith had indeed stripped a lot of parts from the Mosquito for use around the farm. That is why farmers bought airplanes after the war; to use parts and materials that couldn’t easily be acquired during and after the war. That included sturdy wheels for carts and wagons, rubber tires, sheet metal (though in short supply on a Mosquito), hydraulic rams, glycol, steel cable, lead weight, fuel tanks, nuts, bolts and of course an altimeter which graced the dashboards of hundreds of tractors and farm trucks for decades across Western Canada.

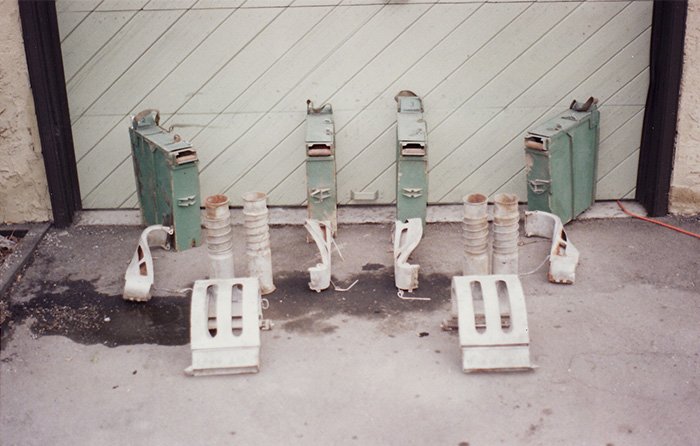

Farmer Smith still had all of the parts he had removed and for the most part had kept them indoors. All he wanted for this treasure trove was for Jon to replace the Mosquito hydraulic cylinders that he was still using around the farm. For the price of a couple of Princess Auto specials [Princess Auto is a well-known Canadian retailer specializing in farm, industrial, automotive, and hydraulic parts and equipment], Jon acquired a truckload of Mosquito parts, that for a half share in a Bolingbroke became mine. I was thrilled. It was 1992 and I had the beginnings of a Mosquito project.

A pair of Canadian-built de Havilland Mosquito main wheels (top) and rudder pedals. All had been kept indoors since being removed from KA114 and showed no overt signs of corrosion. Photo: Richard de Boer

The single car garage in our townhouse condo served as the storage location for these and many other treasures. I managed to talk my wife out of her indoor parking space by convincing her that this ‘dirty junk’ was in fact a collection of rare, valuable and rapidly appreciating artifacts. When it came time for the divorce a few years later, that rationale proved to be an expensive tactical error.

To most, this is unusable scrap, but to a millionaire rebuilding a Mosquito for his private museum, these parts are Holy Grails—almost impossible to find. In the top photo, we see a complete set of Mosquito hydraulic rams for the undercarriage (left), bomb doors (on wall) and flaps (on ground), along with a tail wheel shock strut with retract jack (at right). In the bottom photo, we see .303 ammo boxes with feed chutes in the back, with 20 mm cannon blast tubes (cylinder shapes) and feed chutes in the fore. In the collection were also fuel tanks, cowlings, radiator trays, universal bomb carrier and a triple pneumatic gauge. Photo: Richard de Boer

In the messy and expensive trauma that can be divorce, dreams can take a serious beating. One of those dreams was my ‘Mosquito project’. To add insult to injury, the “rare, valuable and rapidly appreciating artifacts” ended up being sold for about 10 cents on the dollar, even at 1996 values. Some gentlemen from the Canadian Historical Aircraft Association in Windsor, ON came and hauled them away for their Mosquito project. I consoled myself with the thought that at least they had gone to a good home.

A few years later, I got a phone call on a Sunday afternoon from a gentleman with a high-pitched voice and a distinct southern American accent. “I been calling around and people tell me you used to scrounge up old airplanes. Ever come across any Mosquito parts?” the caller asked.

“Yes, I have” I told him and then I asked who was calling.

“This is Jerry Yagen of the Military Aviation Museum in Virginia Beach” he answered.

“Oh dear, Mr. Yagen. This is sadder than you can imagine. Not only do I know what you are looking for, I used to own most of it, and it wasn’t just from any old Mosquito; it was all from your very airplane.” I told him.

I went on to explain how I came to acquire the parts and how I came to lose them. At the end of my sad little story Jerry said “Well that’s a damned shame because I’d-a bought those parts from you, as well as the truck you hauled them in, the garage you stored them in and the house you were living in!”

I didn’t know whether laugh or cry. Before I had a chance to do either, I remembered one of my acts of petty defiance during the divorce process. I had kept the triple pneumatic gauge from the collection of Mosquito parts. It was as good as new and had been displayed in a prominent place as a prized possession in each of the dozen places that I bounced to and from in the years after the divorce. I asked Jerry for the address of the shop that was restoring the Mosquito and I promised him I would send it there. He suggested that it would probably be the only original piece in the instrument panel. It cost me $75 in postage to mail it to Avspecs in New Zealand, but it felt good to know that it would be reunited with the airplane.

Despite the loss of my very last genuine Mosquito part, I maintained my passion for the type. In 2007, I heard rumors of a $1.5M deal to sell the Mosquito that was stored in Calgary to an overseas buyer. I started a campaign to prevent the sale and to see the airplane finally restored. That campaign lasted as long as the Second World War (longer than the war if you are American) and often felt like the Second World War. It got very nasty with lots of people jumping into the fray on both sides of the debate.

The ‘Calgary Mosquito’ was an ex-Spartan Air Services aerial mapping airplane that had been acquired in 1963 by Lynn Garrison for his dream of an ‘Air Museum of Canada’. When the organization failed, the City of Calgary took possession and ownership of this and several other abandoned airplanes. In 1975 the newly formed Aerospace Museum of Calgary was created in order to restore and display the City owned collection.

The Calgary Mosquito was purchased by Spartan Air Services of Ottawa, Ontario. In the 1950s she was registered as CF-HMS and modified for high-speed, high-altitude aerial photographic survey work in the Canadian North. Here, we see her at Edmonton, Alberta around 1959, fuelled up and ready to head north to more remote forward bases. Spartan operated a very diverse fleet of war surplus aircraft including Mosquitos, P-38 Lightnings, an Avro Lancaster, Avro Ansons, Lockheed Venturas, Canso flying boats, DC-3s, Bell-47 and Boeing Vertol helicopters among others. Interestingly, Spartan was the world’s only civilian operator of the de Havilland Sea Hornet, acquiring it directly from the RAF at Edmonton following cold weather testing there. The RAF did not want to pay to have it transported back to England. It was flown until 1952 when it was damaged after a forced landing at Terrace, BC. Photo via the Author

Canadian-built de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito operating from a remote and rough airstrip which Spartan had built at Pelly Lake, Northwest Territories (Now Nunavut) in 1958. Spartan’s work with Mosquitos in the far North faced extreme logistical challenges for fuel, maintenance and weather information. Photo via the Author

In true Canadian ‘Snowbird’ tradition, the Spartan photo-mapping aircraft headed south for the winter, when operating in the North was impossible. Here CF-HMS is seen in Cucuta, Colombia with another fine Canadian de Havilland product, a DHC-2 Beaver. Spartan used their fleet to fulfill aerial survey contracts around the world—place like Argentina, Bahamas, Bélize, British Guyana, Canada, Columbia, Dominican Republic, India, Iran, Kenya, Laos, Liberia, Malaya, Mexico, Mozambique, Nigeria, Peru, Philippines, Seychelles, Somalia, Tanzania, Togo, Trinidad and the United States. Photo by Spartan navigator Bob Bolivar

At one point during the debate over whether to sell and export the Mosquito, a city alderman who supported the sale tried frightening people with big numbers during a radio interview, by saying that he knew of a Mosquito being restored in New Zealand that was going to cost $15,000,000. At that time, there was only one Mosquito being restored in New Zealand. Its owner, Jerry Yagen, heard about this wildly over the top claim.

A few days later I had a voice mail message from Jerry Yagen telling me in heated tones to give him a call and that he would gladly share with me how much he paid for every ‘damned’ part of that airplane. When I called him the next day, he had the file open on his desk and item by item, outlined what he paid for the mortal remains of KA114, for the engines and props, assorted bits and pieces from around the world and a new Glyn Powell Mosquito airframe. Armed with the facts, I was able to refute the alderman’s wildly exaggerated claims about the cost of restoring Calgary’s Mosquito.

In the end, the newly-formed Calgary Mosquito Aircraft Society (CMAS) won the fight to keep and restore not just the Mosquito, but the City of Calgary’s Hawker Hurricane as well. In the process, the City acknowledged the rarity and significance of the airplanes and agreed to fund half of the cost of restoring both airplanes to run and taxi status. We were on the hook for the other half.

Moving Day: 11 August 2012. Crating up the collection of parts that used to be a Spartan Mosquito in order to truck them from a warehouse in Calgary to the Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, Alberta. After campaigning for more than five years, the Calgary Mosquito Society reached an agreement with the City of Calgary to retain and restore its Mosquito to non-flying condition. Photo via the Author

Parts come from a wide variety of surprising places. Calgary Mosquito Society volunteer and board member Andy Woerle trial fits a nose blister on the Mosquito at Nanton, Alberta. The rare component was recently acquired from a couple from Nova Scotia who was out Saturday morning scouting garage sales and spotted it on someone’s lawn. Photo via the Author

Calgary Mosquito Society (CMS) volunteers Gary Toffelmire, Dave Duh and Dick Snider, work at the forward end of the fuselage at Nanton. Over the past five years, an army of around 15 CMS volunteers has turned out each Saturday to swarm over the fuselage and work tables, contributing more than 22,000 hours to date. Photo via the Author

From first rumour of a sale in 2007 to signing a contract with the City of Calgary to restore the Mosquito in 2012, my board members and I made a lot of connections and attended a lot of provincial, national and international conferences to learn, connect with others and support our goals. In 2013, Jack McWilliam, now Vice-President of CMAS and the leader of the actual restoration on the Mosquito, and I attended the Smithsonian-organized and sponsored Mutual Concerns of Air and Space Conference being hosted that year by Seattle’s Museum of Flight. On the first day of the conference we were encouraged to stand up and introduce ourselves and give the 30 second ‘commercial’ on the organization we were representing. The next day as we were catching the bus from the hotel to the museum, a large affable Englishman sat next to me and introduced himself. “I’m David Hunt and I am with the Military Aviation Museum in Virginia and we have a flying Mosquito” he told me.

“I’ve heard about it. Congratulations” I replied, not feeling the need to elaborate.

“As you are from Canada and have a Mosquito, I have to tell you this story that Jerry related to me about this fellow in Canada who had a collection of parts from our airplane. Incredible really…”

Now I could laugh about it.

Richard de Boer

Tragically, Jon Spinks died of leukemia in 1995 at the age of 28. The Bomber Command Museum of Canada said this about John: Jonathan Spinks studied history at the University of Lethbridge. But the history he enjoyed most was not to be found in the books of the University of Lethbridge library. Jon loved to go “airplane hunting” and at this he was both an expert and ahead of his time.

At the age of fifteen, he realized that there was a wealth of historical artifacts and in some cases entire airplanes, unappreciated and for the most part forgotten, in farmer’s yards, sheds, and junk piles all across western Canada. Focusing on the Lancasters, he methodically mapped the locations where they had been broken up for scrap in the early 1950s and searched for the leftovers—gun turrets, instrument panels, pilot’s seats, bomb bay doors, escape hatches, and anything else he could find. He also searched for aircraft and artifacts of the BCATP.

Clearly a visionary in the appreciation of the value of these treasures, Jon trained and inspired members of the Nanton Lancaster Society in his chosen field of “airplane hunting.” His efforts and enthusiasm were responsible for the Society acquiring numerous aircraft and artifacts from the farms of southern Alberta.