WILDMAN

When reading or researching history, it is easy to be drawn to the brightest lights, to be mesmerized by and enamoured of uncomplicated storylines, to wish for heroes and villains, to see only the deepest of blacks or the most blinding whites. We like our heroes and their enemies to be one-dimensional—dashing and nonchalant Etonian fighter pilots in the Battle of Britain, apple-cheeked American B-17 belly-gunners, duelling-scarred and shark-faced Messerschmitt pilots with cruel, blue eyes or fresh-faced Saskatchewan farm boys in the dead of night over Berlin. Sometimes the darks and the lights of simplicity and order wash out the margins of a story wherein the truth lies. Here are stories of two men who followed two very different paths that led to two very different outcomes. They were cousins, related through birth and DNA, though it is quite possible that they never met. One is the epitomic story of the brightest of the bright, the other, a story of darkness and fall from grace. Or so I thought.

It is safe to say that the great majority of pilots and aircrew in the English-speaking world have read or heard the uplifting and joyous words of the poem known as High Flight, written by John Gillespie Magee Jr., a teenaged Anglo-American Spitfire pilot of His Majesty’s Royal Canadian Air Force. It has been pinned on the bulletin boards of a thousand flying clubs, read at the funerals of astronauts and pilots across the globe and inspired nearly every living pilot to take a moment to realize the spirituality of the very act of flying. I personally have read it at two funerals and I do not know a single aviator who is not familiar in some way with its spiritual rhythm.

John Magee did not live long as a combat pilot but he did, however, live just long enough to pluck 114 words from his heart and string them together to form a hauntingly perfect descriptive strand of aviator DNA. In these words and lines can be found the emotional and inspirational genetic code that reveals the aviator, that explains the passion we have for flight, that inspires us to climb sunward.

His were not the words of modern aviation, of GPS, glass cockpits, air traffic control, and launch and leave. His are the words that describe human flight before utility. Of wings and clouds and three dimensions. Of flight before external controlling forces, technology and regulation chipped away at the joy. His words describe the aviator of the First World War, of barnstorming, of his own war and of today’s working aviators who still sense that fundamental rolling and scissoring strand of DNA deep in their bodies—a strand that traces a hidden line from their exultant hearts to their poetic minds. A strand that reveals itself as a tingle rising up the connecting spine.

Though John Magee was flying Spitfires at the age of just eighteen, he was a particularly thoughtful young man, who, despite being deeply thrilled and moved by flight, saw his role in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) as protector and avenging angel for his beloved England—an England in great national stress at the time of his arrival there as a fighter pilot. His contemplative soul and his strong sense of right and wrong were formed by his Christian upbringing, his loving and dedicated parents, his rich education and his international early life.

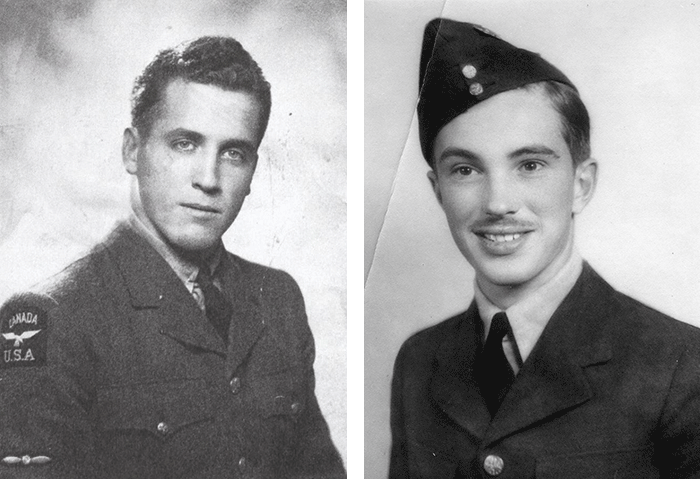

John (left) and Chris Magee, fighter pilot cousins—both American, both trained by the Royal Canadian Air Force, both poets and writers fighting at opposite ends of the earth. One died, one lived, but both would become legends.

As a student of the “emotional history” of the men and women aviators of the Second World War, I have come closer to knowing young John Gillespie Magee Jr. than most, but not nearly as much as others and not nearly enough to truly know him. He flew from the runways of No. 2 Service Flying Training School, about a 15-minute drive from where I am writing this. He once slept in a home just around the corner from my house. 412 Squadron, the Spitfire unit he flew with in the Second World War, has been stationed in Ottawa since 1947 (8 years at Rockcliffe and 62 years at Uplands). Many of its former and present pilots and a few of its commanders are my friends. His spirit has lived in the hangar at Vintage Wings of Canada for more than a decade and his name has graced the side of our Harvard trainer which is painted in the markings of one he flew here in Ottawa in 1941. In all that time, I have come to know him very little. To me he was and still is perceived as the poster pilot for innocence and purity of intent—the shining Galahad of the Royal Canadian Air Force, a character of Arthurian qualities who is cut down before the fight—like the boy soldier at the front in the First World War who is first over the top, only to be shot dead as he takes a first step toward the enemy. To most of us, he is more of an ideal than a flesh and blood man. The more he is studied, the less the importance of the poem he is known for and the more he comes to represent the Arthurian standard—youth, courage, determination, purity of purpose and boldness of heart.

John Magee was, to be certain, a human being first; one with the fears, doubts and bad habits we all have and try to conceal. But I never saw him in anything but the bright white light of his legend. Never imagined him in those shades of grey that colour our own lives—trepidation, fragile self esteem, longing, homesickness, humour, anger and anxiety. I see him through his photographs, not his letters. Lately, however, I have come to wonder about him as a young man and not an icon. The cause of all of this was learning the story of his cousin, another Second World War fighter pilot by the name of Christopher Lyman Magee.

Both John Magee and Chris Magee were scions of a notable and wealthy Scottish-Irish family from Pennsylvania whose most notable member was the patriarchical Christopher Lyman Magee, a Pennsylvania State Senator, Republican politician and industrialist from Pittsburgh. The two flying Magees came from different offshoots of the family tree—their grandfathers were brother and half–brother of the great patriarch himself. John Magee’s father, John Gillespie Magee Sr., was a Christian missionary in China where the young Magee was born. Chris Magee was born in Omaha, Nebraska but was raised in the South Side of Chicago where his father Frederick McNichol Magee worked for the grain market exchange. Given that Magee was born in Shanghai and educated in England and Chris Magee grew up, went to high school and attended the University of Illinois, it is most likely that they barely knew of each other, let alone ever met.

The two cousins could trace their lineage to Christopher Lyman Magee, a prominent Pittsburgh businessman and an influential member of the Pennsylvania State Senate for Allegheny County, his brother Frederick McNichol Magee, a Pittsburgh lawyer and his half-brother Edward Simpson Magee. Frederick McNichol Magee was the father of John Gillespie Magee Sr., the highly-educated Christian missionary whose son was John Gillespie Magee Jr. of High Flight fame. Among Frederick McNichol Magee’s seven children was another Christopher Lyman Magee (a boy who died at the age of 7 years in 1878) and James McDevitt Magee, an early American aviator and perhaps the avuncular inspiration that led to the cousins Chris and John Magee becoming flyers. To make things even more confusing, Frederick McNichol Magee’s half-brother Edward Simpson Magee was the father of another Frederick McNichol Magee—the father of the future Marine ace Christopher Lyman Magee. Clearly the family selected names from a very short list and had a tradition of second names being derived from surnames of friends and business associates (McNichol, Simpson, McDevitt etc.). Confused? So was I. Photo: legis.state.pa.us

This story began as two parallel but separate stories meant to contrast with each other—the short and holy fable of John and the long, anti-conformist adventure that was Chris Magee’s tale. As you will see, Chris’ extraordinary and sometimes dark epic hijacked my intentions, and this story dragged me down the trail of discovery of an extraordinary man. A man loved by his fighter pilot comrades for his free spirit and eccentricities, but one destined to travel his long hard road alone. For those who wish to learn more about John Magee, please see two stories on this site: Magee—The Boy Hero and Poet Legend and Finding Magee.

I first came across Chris Magee’s story when I was researching material about his RCAF cousin. On the Wikipedia page dedicated to him, I read the words “Wildman… Navy Cross… ace… Black Sheep squadron… black marketer… bootlegger… covert group… drifted between jobs… Haganah… divorce… bank robbery and Leavenworth” and thought I had a great story for some future date. To be honest, I saw a story that contrasted Chris, a screw-up who had squandered his heroic legacy, with John, the standard for purity of purpose and unspoiled innocence. I saw this story in black and white with Chris Magee a foil to John— a story that would leave your head shaking at the distance between their points of view and paths taken. However, I could not have been more wrong about Captain Christopher Lyman Magee of Chicago, Illinois.

After a couple of years, I started researching his story and realized I would have to order copies of two books in which Chris Magee plays a major part—Once They Were Eagles: the Men of the Black Sheep Squadron by Frank E. Walton and Lost Black Sheep: The Search for WWII Ace Chris Magee by Robert T. Reed.

Frank Walton, a former Los Angeles Police Department cop, was the squadron Intelligence Officer for VMF-214, the highly successful and much publicized Marine Corsair squadron that operated ever so briefly (just 84 days) in the Solomon Islands of the South Pacific in the Second World War. Though not a pilot, Walton was much loved by his pilots for the professionalism he brought to his job, for their shared hardships and for his key part in publicizing their exploits and establishing their public reputation as an aggressive and colourful combat fighter unit. When the television series Baa Baa Black Sheep first debuted in 1976, Walton was appalled the “hoked-up phony, typical Hollywood-type of production” that characterized his unit and his friends “as a bunch of brawling bums who were fugitives from courts-martial.” He decided then to try to track down all 34 surviving members of the original 51 pilots and officers of the Black Sheep and organize a reunion. In the end 17 men (most with their wives) met in Hawaii and relived that intense period of their lives. After a second reunion in 1980, Walton got the idea for his book and set out to meet and interview each surviving member, criss-crossing the country spending anywhere from a few hours to a few days with each man.

There was only one man for whom the trail had gone cold—Chris Magee. Few of the other pilots had had contact with him since the end of the war (no one had any contact for decades) and no phone books or research could dig up his address or phone number. Being a former policeman and Foreign Service worker, he enlisted friends in the FBI to help track down an address. Though Walton was not able to speak directly to Magee for his book, he did have one of his letters answered. Any follow up correspondence to arrange a place to meet also went unanswered, so Walton simply transcribed that letter for his book about the Black Sheep days.

I received Reed’s book first, and the opening pages, with an excerpt from Walton’s highly-regarded book, changed my mind and heart about Chris Magee immediately. These were words written by the Lost Black Sheep himself and showed an intelligent, contemplative, honest and somewhat melancholy man.

“Chris “Wildman” Magee was perhaps the ultimate combat fighter pilot. Utterly fearless and totally aggressive, he had the knack of knowing where the action was, plus complete mastery of the airplane; he could make it do things no other pilot could. His record of nine Zeroes was exceeded in our squadron only by Boyington’s total.”

“Maggie [his fellow pilots called him by this name-Ed] turned out to be one of the most difficult Black Sheep to locate. When I finally found him, I understood why. He had a most colorful career.”

“After the war, he’d joined the Israeli Air Force during their war of independence. Following that service and his return to the States, he had run into some difficulty with the law; as a result, it took the assistance of my friend, the Chief of Police of Los Angeles, and the FBI to locate him. Finally, I received a letter from Maggie.”

Greetings, Frank

Strange how a few words can do more to reveal something of the nature of time that all the equations a team of Einsteins could formulate in a lifetime of blackboard gymnastics. It isn’t so much that words throw a bridge across a considerable gulf between “now” and “then” events as it is that they collapse all intervening activities below consciousness, and unite the “now” with the “then” as if by some alchemical implosion, some magic infusion.

Such, somehow dramatized, was the effect of your letters, which I picked up recently when I dropped by my former pad in Chicago Southside to check the possibility that mail may have strayed that way.

I’ve been to Florida a couple of times this year, roving the Gulf Coast, into the Everglades, and down to the Keys. And Westward Ho! Too. Colorado etc.

A change of pace after six years as editor/writer/reporter for a Chicago community newspaper of approximately 30,000 circulation.

Aside from two days and nights of intense involvement every week, I was free to set my own pace, so there was some compensation in terms of freedom, which I needed.

There was further compensation in the form of a discipline imposed by the ever-present demand of the next deadline. But once a week for six years is a bit too much of that kind of compensation for me.

The paper was sold and the new owner brought in his own editor, so I am free of the printer’s ink mold, and have spent a number of months recuperating from a bad case of brainlock, induced by an overexposure to journalese.

Before that job, I edited another community newspaper for a couple of years.

Previous to those forays into the legitimate, I was a house guest of J. Edgar Hoover at his resorts in Atlanta and Leavenworth, where due to SNAFU bureaucratic behavior in the manner of record keeping, teamed with a paranoiac penchant for secrecy, my durance vile went considerably beyond what evidently had been intended.

During my sojourn, I taught a wide variety of high school classes, picked up some 80 college credits via extension courses, and became editor of Leavenworth’s quarterly magazine, “New Era”, a slick 50-plus-page organ with pretensions to literary excellence. In fact, it was included in a survey and index of literary “Little Magazines.” We also had close and friendly ties with Engel’s famed Writers’ Workshop at the State University of Iowa.

Some of my work was reprinted in other publications around the world that were oriented to more esoteric fare. For instance, the Sri Aurobino Ashram in Pondicherry, India. I was deep into the psycho-spiritual thing long before the recent boom began. And I don’t mean the Tim Leary, Baba Ram Das, Allen Ginsberg, Holy Man circuit bit, or any of this swooning over Eastern mysticism. The West has its own tradition, only touched upon by C.G. Jung.

Anyway, retreating farther yet, timewise, I was active in the Caribbean area in the mid-1950s, and before that was working with construction crews in Greenland, above the Arctic Circle, setting up the air warning network. Earlier, in 1949, I was in Aspen, Colorado, tape recording highlights of the Goethe Bicentennial Celebration, the event that kicked off Aspen’s ascent to an off-the-beaten-path cultural center. Albert Schweitzer (Reverence for Life) was guest of honor; his first absence from Africa in 25 years.

In 1948 I was flying Me 109Gs for the Haganah in Israel (while Herr Hitler did snap rolls in his Nazi hell. Must have been a blowtorch on the bollocks to hear about Jews in Messerschmitts!). But that wasn’t until I went through a cloak and dagger underground smuggling operation in New York and Europe.

So, that’s a fair abbreviation of my post-Black Sheep days. Although there are those who would say, cynically of course, that for me they never ended, that they in fact became more than an upside-down euphemism, more than a play name adopted by a bunch of great guys who, it would be almost miraculous to reminisce with over a vat of milk punch.

Well Frank, it was a high, hearing from you. I’d enjoy being on the receiving end of any other information you seine from the stream of years.

“Chris enclosed one of his own published poems, entitled Postscript from “One Who, Like His Age, Died Young” and prefaced by the following note: “Several years after World War II, the wreck of a U.S. Marine Corps fighter plane was discovered in the interior jungle of New Ireland, in the Solomons, by a former Royal Australian Coast Watcher. A jungle kit was recovered from the cockpit of the Corsair; among its items of survival gear was a wax-sealed, fungus resistant plastic folder containing a box of ammunition for a .45 automatic and a sheet of paper with these lines.” ”

I have skimmed the ragged edge of lightning death

And torn from bloody flesh of sky a thunder song.

Across the nakedness of virgin space

I’ve blistered my frozen hand in feathered ice

And dared angelic wrath to smash

The snarling will of my demon steed.

Far above the sun-glint on winded spume,

High executor of laws no man has made,

I’ve welded Samurai knights into fiery tombs

And hurled them down like the plumed Minoan

Far down the searing heights to punch

Their livid crates in the sea.

‘Enemies,’ you say. They were not mine.

More than blood brothers, I swear,

With tawny skin and warrior eye.

Bushido-bred for hell-strife joy.

Much closer my kin, may race than those

Who cud-chew their lives can ever be.

‘War-lover,’ you say, ‘sadist, psychotic’—

That sick cycle of canned clichés masking

Your lust for eternity fettered to time.

Go, epigonic pygmies, make peace with hell,

Drag the myths of our ancient might

Through the miserable muck of a cringer’s dream.

What could you know

Who have never heard

The soaring song of the Valkyries,

Felt thunder-gods jousting with livid peaks:

You who have never dared to walk the razor

Across the zenith of your peevish soul?

“Subsequent letters to Chris’ address have come back marked “Return to Sender—Unable to Forward.” Possibilities as to where he is and what he is doing are endless. He may be in Central America; he may be involved in another secret mission somewhere in the world; in view of the Middle East situation, he could very well be back with the Israeli Air Force; he may be in Africa. Like Kipling’s Cat Who walked By Himself, “He went through the wet, wild woods, waving his old tail, and walking his wild lone. But he never told anybody.” ”

“He may have passed on to Fighter Pilot’s Heaven. I certainly hope not. The world has desperate need for free spirits, even those who suffer occasional aberrations.”

This transcribed letter and the poem it contained altered the planned course of my story. Originally, my story was to be about the things they didn’t have in common—how one young man was illuminated in bright white and elevated to mythic status while the other, like Lucifer, had fallen from grace. But having read the opening to Reed’s heartfelt book and the excerpt from Walton’s, I knew that Christopher Lyman Magee was as extraordinary, as intellectual, as poetic and as worthy of my admiration as his distant cousin. By the time I finished both Reed’s and Walton’s books, Chris Magee’s elusive persona took its complex shape in my imagination and in my heart. He was to become for me a man of unique behaviours and attitude, a man who sought to understand the framework of his own proclivities and experiences. A man who saw his enemies as brothers he would both love and destroy. A cross between Hunter S. Thompson, Saburo Sakai, John Dillinger and Clint Eastwood’s Walt Kowalski from Gran Torino. A Marine Corps beatnik. A zigger among zaggers. The ultimate individualist.

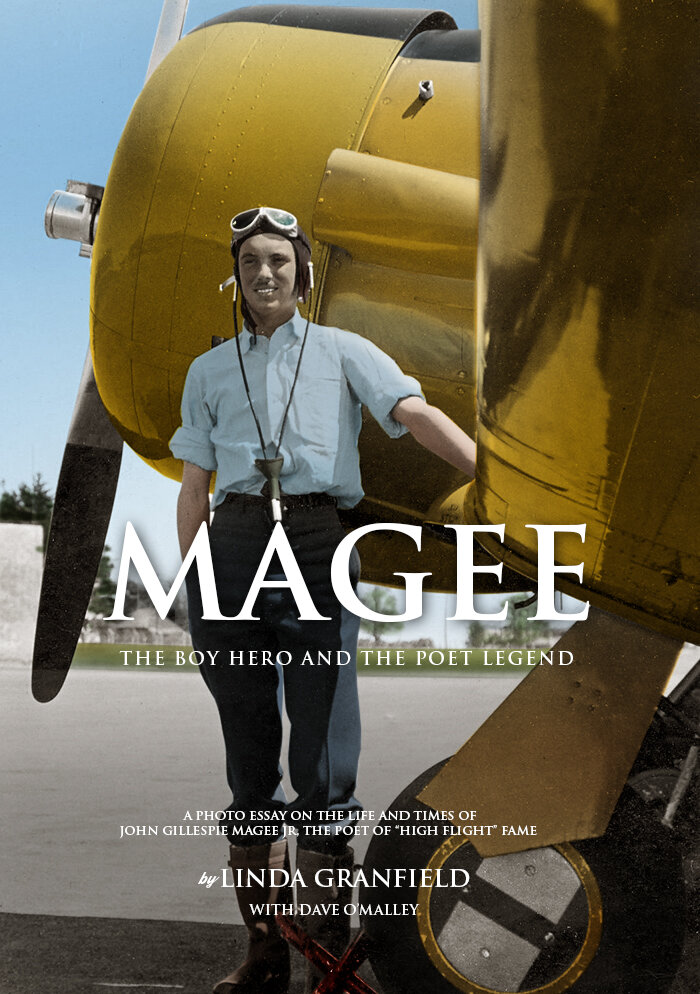

It had always been my intention to write about both cousins in balance, but I have found myself profoundly drawn to and moved by the story of the older cousin, Chris. Now, this is partially because over the past ten years, we have covered the complex, international, highly romantic and tragic story of his distant cousin many times in Vintage News. John Gillespie Magee Jr.’s story is well known thanks to creative and impassioned writers like John Magee’s biographer, Linda Granfield and dedicated researchers like Rob Kostecka and Ray Haas. I think it’s time that we all learned a little bit about Chris Magee and the extraordinary maverick life he led.

Like his cousin John, Chris Magee, the first-born son of Fred and Marie (nee Mary Ellen Considine) Magee, was born far from the Magee family’s Pennsylvanian root structure, in 1917 in Omaha, Nebraska. A year later, he moved with his parents to Chicago’s South Side. Growing up, the young Magee was known by family and friends as “C.L.” and soon developed a reputation among his friends for adventurous and sometimes dangerous behaviours and pursuits. Each summer Fred and Marie would pack Chris, his sister Zona and younger brother Fred Jr. off on the train to spend time with their Pittsburgh cousins and extended families.

Throughout high school, Chris Magee balanced his native love of sport and physical fitness with his passion for reading and learning—a combination of mind and body he would maintain all his life. Following graduation from Mount Carmel High School, Magee kicked around the South Side, working a bit, pushing the edge of trouble with bookies, all the while working out. Today, young men working out on weights at gyms are commonplace, even the norm, but back in the midst of the Great Depression, weight training was an uncommon pursuit. It was during the three years between high school and his enrollment at the University of Chicago in 1938 that Magee took up his lifelong commitment to weight training, growing from rail-thin to heavily muscled. In his freshman year, he played end with the UC Maroons freshman varsity team and excelled in track and boxing.

As war loomed and then broke out in Europe, Magee lost focus at university and began itching to get into the fray. About the same time, his younger 17-year-old cousin John was in Pittsburgh visiting his aunt. He too began itching to get into the fight, but for a different and perhaps more altruistic reason—he wanted to return to England in her time of need, to join his friends, to fight the evil of Nazism and help save the homeland of his mother. His first thought however, being brought up by Christian missionary parents, was to help his fellow man by joining the British Ambulance Corps.

By January of 1940, Chris Magee’s sense of adventure and outrage, combined with his new existential thoughts about warrior culture developed from his readings, and his desire to test his body, mind and metal in combat led him to hitchhike with two friends to New Orleans to find passage to Europe as deckhands on a freighter. After weeks of attempts, it was clear that their American citizenship, neutrality laws that prevented him from getting a visa and time were conspiring against them. Magee and one of his friends stuck out their thumbs once again and worked their way home to Chicago. But he was not defeated.

Upon hearing that Canada was accepting American men in the Royal Canadian Air Force, he travelled to Windsor, Ontario across the river from Detroit to join up. Unfortunately, he learned at the recruitment office that the RCAF required a college degree for enlistment for pilot training—more college credits than he had amassed in his lackluster year at university. He returned home to Chicago and turned his efforts to getting enough credits (two years of college or equivalency) to enter the US Army’s flight cadet program, now, in his mind, the only route to a war that he was sure would inevitably involve Americans directly.

Around the time that Chris Magee was hitting the books—seriously for the first time in his educational life—John Magee also went to Canada to enlist in the RCAF. His attempts to get back to England and the Ambulance Corps had been thwarted by his young age and the same regulations that had stymied Chris Magee’s plans. At the time he had enlisted, The RCAF had reduced its requirement to two years college, but the younger Magee had no college credits. Perhaps it was his excellent English preparatory and private school education, the award of a scholarship to Yale or his mother’s British citizenship, but he managed to enlist in the RCAF with the goal to become a pilot. Despite being more than five years younger than Chris, John Magee now had a head start on his cousin.

Chris Magee studied hard for his 2-year college American equivalency test, passed and was accepted in a US Army flying program that would not begin until March of 1941. Still anxious to get to the war as soon as humanly possible, he went back to Canada where he learned that his equivalency test was not accepted and that two full years of college were required. However, he also learned that there was an exception for men who had a minimum of 35 hours of flying time in their logbooks. He devised a rather devious plan to acquire those hours. He would indeed attend the March flying training program, but when he accumulated 35 hours of flying time, he would wash out, take the train north and finally enlist in the RCAF.

Chris Magee enlisted in the US Army’s cadet training program at the Spartan School of Aeronautics in Tulsa, Oklahoma and amassed 25.5 hours of dual flying time and 10 hours of solo flying in the Fairchild PT-19. As his total approached 35 hours, he feigned incompetence and was washed out. He declined retraining for another flying trade such as navigation, resigned from the course on 20 May and headed north with his logbook. At about the same time, cousin John was living in Ottawa and just finishing up his advanced flying training on Course 25 at No. 2 Service Flying Training School, Uplands. On the day that Chris resigned from the US Army, John went flying solo four times in the skies near Ottawa, practicing formation flying and aerobatics. The younger John Magee would win his coveted RCAF pilot’s brevet on 16 June, heading shortly to Halifax, Nova Scotia and then to the war. Chris Magee had yet to truly start.

Related Stories

Click on image

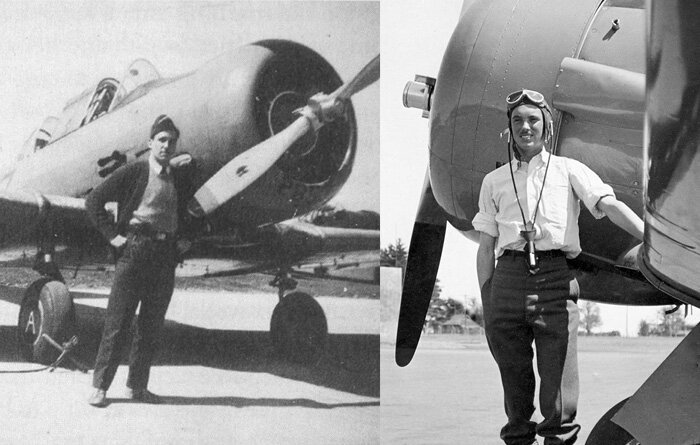

Two photos of Chris Magee taken during his training—one in Canada, one in the United States. On the right, Magee is photographed in front of a Fairchild PT-19 in full leathers at the Spartan School of Aeronautics in Tulsa Oklahoma. Magee started his flight training as a member of the United States Army in April 1941 but felt that since the US was not in the war he would build the minimum of 35 hours flying time required to join the RCAF through the Clayton Knight Committee route. Once he made his 35 hours, he feigned incompetence and washed out, making his way to Canada. At left, in January of 1942, a young Magee strikes a confident pose while flight training on Fleet Finch open cockpit biplanes at No. 21 Elementary Flying Training School at Chatham, New Brunswick. Photos: Lost Black Sheep—The Search of WWII Ace Chris Magee by Robert T. Reed via Google book

In early July, the redoubtable Chris Magee, after a dirty coal car train ride to Toronto from Windsor, finally managed to enlist in His Majesty’s Royal Canadian Air Force. Shortly thereafter, he received orders to travel by train (a passenger car this time) to Lachine, Québec to begin air force training as an Aircraftsman Second Class (AC2) at No. 5 Manning Depot. It was at a Manning Depot that new recruits would learn the rules of the RCAF—how and who to salute, marching drill, spit and polish, and the fundamentals of life in the air force in Canada. In Reed’s book, he states that Chris did his basic training at St. Hubert, but that is not possible as the only other Manning Depot in Québec where this kind of training took place was 160 miles to the northeast in Québec City. There is no doubt that he would have done his basic airman’s training at nearby Lachine (across the St. Lawrence from St. Hubert), then possibly doing guard duty at St. Hubert. This kind of guard duty was standard operating procedure as there was always a bottleneck between Manning Depot and Initial Training School (ITS) and then again before entering Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS).

It seems that during his stay at No. 5, he felt that English-speaking Canadians and their American friends were not entirely welcomed by French-speaking Montrealers. Perhaps it was his pugilistic character and his penchant for bar fighting that failed to endear him with the locals. While Chris was champing at the bit to get moving at Manning Depot and taking his frustrations out on the local “taverniers”, on 18 August 1941, John Magee signed out a war weary Spitfire Mk I from the flight line at No. 53 Spitfire Operational Training Unit based in Llandow, Wales and took it aloft for two full hours of inspired solo flight, beginning at 32,000 feet. The result was the loss of several hundred gallons of His Majesty’s 100 octane fuel and the visceral inspiration for the literary world’s finest expression of the exhilaration and spirituality of flight—the poem we all know as High Flight. The young John Magee, writing home to his parents, called it simply “a ditty”.

Two photographs of the Magee cousins taken as they began their pilot training as Leading Aircraftmen (LACs) of the Royal Canadian Air Force. The confident and challenging face of Chris Magee (left) contrasts with the boyish innocence and open face of his cousin John. Chris would do his Elementary Flying Training at No. 21 EFTS in Chatham, New Brunswick, while John completed his at No. 9 EFTS in St. Catharines, Ontario. Photos: Left: Google books; Right: From the Magee Family Archive/Yale divinity School Library

In these photos of the young Magees during the Service Flying phase of their pilot training, Chris (left) at No. 9 SFTS Summerside, Prince Edward Island, and John (right) at No. 2 SFTS, Uplands in Ottawa pose with the Harvard II training aircraft in which they would earn their wings. Chris is already demonstrating his sartorial independence wearing two non-regulation sweaters and light coloured footwear. In his wedge cap, Chris Magee wears the white ribbon flash an aircrew student in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. This was worn by student pilots, navigators, flight engineers, gunners, radio operators and bomb aimers. Photos: Left: Google books; Right: DND

As was nearly every airman who entered the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan at any time during the war, Chris was disappointed with the progress of his personal plan towards flying training. Immediately after Manning Depot, he spent six long and boring weeks on guard duty at an RCAF storage depot‚ possibly RCAF Station St. Hubert on the south side of the St. Lawrence River across from the City of Montréal. This was known in the lingo of the day as “Tarmac Duty”. Some were sent to factories to count nuts and bolts, some were sent to flying schools and other RCAF facilities to guard things, clean things, paint things, and polish things. Tarmac duty could last several months or more.

Following this, he was assigned to No. 3 Initial Training School at Victoriaville, Québec in a region south of the St. Lawrence River known as the Eastern Townships. Victoriaville is known to many hockey-playing Canucks for the quality of hockey sticks once made there. The school was housed in Sacred Heart College, a former Catholic school/seminary.

One of seven such training facilities across Canada, No. 3 Initial Training Facility was housed in Collège du Sacré-Coeur, a former seminary in Victoriaville, Québec.

Pilot and air observer candidates did four weeks at an Initial Training School (ITS). Here Chris Magee studied theoretical subjects and was subjected to a variety of tests. Courses included navigation, theory of flight, meteorology, duties of an officer, air force administration, algebra, and trigonometry. Tests included an interview with a psychiatrist, the four-hour long M2 physical examination, a session in a decompression chamber, and a few hours in a Link Trainer as well as academics. At the end of the course the postings were announced. Occasionally candidates were re-routed to the Wireless Air Gunner stream at the end of ITS. As he was nearing the end of his ITS course, the news came that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor and that America had declared war. A few days later, on 11 December, news came over the radio in Victoriaville that America had also declared war on Germany. Magee had already decided to stay on the RCAF track as the fastest route to the fight.

One piece of news that did not reach him was that his just-turned 19-year-old cousin John had died that very day when the Spitfire he was flying collided with an Avro Anson over the English hamlet of Roxholme. While his poem would become immortal and his story burnished by history, the young and idealistic John Magee’s personal story and contribution to the war ended at the graveside ceremony at Scopwick, Lincolnshire with his 412 Squadron comrades surrounding his casket and the sharp report of Lee-Enfields barking a last salute, Now, it was up to his distant cousin Christopher Lyman Magee to write the end to the family’s fighter pilot legacy. And what a story he would write.

Because of his aptitude and his 35 hours of flying, Chris was selected to move on to No. 21 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) at RCAF Station Chatham near the town of New Castle (now known as Miramichi), New Brunswick. No. 21 EFTS provided Magee with approximately 50 hours of basic flying instruction on the Fleet Finch biplane trainer over 8 weeks. Many of the Finches of No. 21 were on skis in the winter and the weather could be very challenging. Elementary schools of the BCATP were operated by civilian flying clubs under contract to the RCAF and most of the instructors were civilians. The school at Chatham was managed by staff and instructors of the Moncton Flying Club. As Chris had already flown 35 hours, it is likely he was flying solo within a very few hours of dual time. The school closed operations at Chatham a couple of months after Chris’ group went through. The entire school and its Moncton Flying Club instructors and managers then moved to Neepawa, Manitoba and continued training Royal Air Force pilots as No. 35 EFTS.

Along with many of his EFTS course mates, Chris Magee would take the train south and a ferry across Northumberland Strait to Port Borden, Prince Edward Island, and then on to his Service Flying Training stage at No. 9 SFTS Summerside. His cadre, Course No. 53, began training on 27 March 1942. He would have had received his wings approximately three months later at a ceremony and parade on 3 July with the rest of his friends had he stuck with it, but American armed forces recruiters showed up at Summerside in the first week of May looking to attract American members of the RCAF. Chris Magee’s main focus was to get to the war as quickly as possible as a fighter pilot. While the Americans could make his wish come true, the RCAF played no favourites and indicated that Magee would go where they told him to go… and that could be even to a training base as an instructor. After more than 300 days as a member of the RCAF, Magee resigned and headed to Naval Air Station Atlanta in DeKalb County, Georgia, armed with the promise that he would become a Marine Corps fighter pilot. He was soon back in the cockpit of a Harvard… or rather, an SNJ, the Navy’s designation for the same aircraft.

Robert Reed, in Lost Black Sheep, relates an interesting point made by Chris Magee: “A surprising number of cadets were killed in crashes during these early weeks of training. Chris blamed this on a lack of night flying and instrument flying, things the RCAF taught pilots in the elementary phase of its program.” After four months of intense flying training as a naval flight cadet, Magee transitioned to the Marine Corps and then was awarded his wings in late November 1942 as a 2nd Lieutenant. By the end of February 1943, Magee was at the fighter operational training unit at Cecil Field in Florida. Here he moved up a notch in his training, flying the Grumman F4F Wildcat. The Wildcat, though a big step up from the SNJ, was, even though deployed throughout the Pacific Theatre, somewhat obsolete as a carrier-based fighter aircraft in the South Pacific, soon to be eclipsed by its next of kin, the Grumman Hellcat and the even more capable Chance Vought Corsair. As a transitional naval fighter trainer, however, it was outstanding.

The stubby, barrel-chested Grumman wildcat was the mainstay fighter for the United States Navy and Marine Corps in the South Pacific in the opening months of the Second World War. Outclassed in terms of performance and manœuvrability by its arch enemy the Mitsubishi Zero, the aircraft nonetheless was able to serve with distinction due to its ruggedness and the creation of defensive tactics like the Thach Weave. Photo: US Navy

Magee worked up on the Wildcat for the next month, then moved north to Chicago where he underwent carrier landing qualifications aboard the paddle wheel training carrier USS Wolverine. Wolverine, along with her sister carrier Sable, were two land-locked, freshwater, coal-fired paddle-wheelers that had been converted from day excursion passenger ships to help train Navy pilots. The pilot trainees lived at and flew from Naval Air Station Glenview on the outskirts of Chicago, while the ships themselves sailed daily from their berths at the Navy Pier on Chicago’s Lake Michigan waterfront.

A US Navy Grumman Wildcat banks over the starboard side of the USS Wolverine (IX-64) lying at anchor on Lake Michigan in 1943, while another Wildcat rips down the port side. The two were likely putting on a display for some event as witnessed by the ship’s crew formed up in dress whites on her deck. For the full story on Lake Michigan’s land-locked paddle-wheeler carriers click here. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Following his carrier qualifications, Magee visited his family in Chicago’s South Side where he attended the wedding of his sister Zona, then headed by train in April to San Diego and Miramar Naval Air Station, there to await deployment to the South Pacific. With not much to do, he played the tourist in Los Angeles and Hollywood, and was assigned temporary duty at nearby Marine Corps Air Station El Centro. Magee was frustrated by inaction and lack of flying. He was likely second guessing his decision to leave the RCAF, where, if all had gone according to plan, he would be in the thick of the European fight by now. Finally, in the first week of June 1943, Magee and his new fighter pilot cohort walked up the gangway of the troopship USS Rochambeau, bound for New Caledonia and the South Pacific war. The journey was interminable, but Magee had brought a sea chest stuffed with books for his mind and a set of weights for his body.

Chris Magee left for the South Pacific in June of 1943 aboard the former French liner Maréchal Joffre. This armed US Navy troopship had been taken by the US in the Philippines after the fall of France, modified and renamed Rochambeau after Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, the French nobleman who had led the French troops in George Washington’s revolutionary army. Photo via eBay

More than two weeks later on 23 June, 1943, after three years and five months of trying to get in the fight, 2nd Lieutenant Christopher Lyman Magee finally stepped off the boat and into the war.

From New Caledonia, he was quickly moved 500 kilometres north to the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) and the island of Espiritu Santo which was a major allied staging point for the war against the Japanese further north in New Britain. Here, Magee began a transition to the mighty Chance Vought Corsair, the ultimate single-engine fighter in-theatre for a man who wanted only to test his metal man-against-man in aerial combat. By the end of July, he was assigned to Marine fighter squadron VMF-124. For the next month, Chris Magee would train hard and accumulate nearly 70 hours on the Corsair, but had yet to engage the enemy when the squadron was abruptly disbanded. Not really a fighter pilot yet, Magee was placed in a pilot pool, where recent arrivals and men from disbanded units were placed pending a new squadron assignment. It was this pool of unattached pilots that gave birth to myth that the soon-to-be-legendary VMF-214 Black Sheep Squadron was created from trouble-maker fighter pilots no one else wanted. This was far from the truth. Their post-war reputation as scallywags, brawlers and drunkards, fostered by the 1970s television series Baa Baa Black Sheep, always sat poorly with the competent, accomplished and courageous pilots that would soon be Chris Magee’s squadron mates and comrades-in-arms. But I am getting ahead of the story here.

Chris Magee was but a few days in this replacement pool on Espiritu Santo, when he and a squadron’s-worth of anxious young pilots were selected to join VMF-214, a Marine Corsair squadron just then reforming after disbandment some months before. Formerly nicknamed “The Swashbucklers”, VMF-214, under the leadership of the brash, pugilistic and uber-competent combat ace from Idaho, Major Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, would, just 12 weeks later have become the most talked-about, respected, and ace-making Marine fighter unit of the Second World War.

A squadron photo of VMF-214 personnel, taken at the Turtle Bay fighter airstrip on Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides, where they formed up. On the day Frank Walton reported for duty as the squadron’s Intelligence Officer, he found them busy getting ready to pose for a squadron photograph. The men are not wearing any flying equipment or even flight suits, and because Frank Walton is not in this photo, I think that this photo was the one from Walton’s first day—7 September 1943. Chris Magee is fourth from the left in the front row. Photo: USMC

A close-up from the previous photo shows Chris Magee (centre in front row) looking confident and ready to fight the Japanese. Among other things, Magee was known for carrying a set of weights with him wherever he moved in the South Pacific and, in this photo, this is evidenced by his broad shoulders. Photo: USMC

The squadron pilots formed a strong bond almost immediately and under Boyington’s leadership struck a casual and fraternal attitude on the ground and an extraordinarily aggressive personality in the air. One of the first orders of duty was to select a squadron nickname that befitted their new persona and their pride in being commanded by Flying Tiger ace Boyington. Their first choice was Boyington’s Bastards, but the submission was deemed too risqué and instead, a Marine public relations officer came up with the name Black Sheep. While the men quickly approved of this new name, it would no doubt also contribute to their future characterization as rejects and reprobates. All that was good about the unit’s legend came from the efforts of squadron Intelligence Officer Frank Walton and all that was unsavoury was created decades later by the television series Baa Baa Black Sheep.

While they were assembling and getting to know each other on Espiritu Santo, the squadron was visited by public relations teams, photographing and filming “operations” by the squadron. This was likely because of the celebrity of Boyington, their new commander, who had been a Flying Tigers ace. Above, a well-circulated and staged photo of the Black Sheep shows them scrambling to their Corsairs on Espiritu Santo, even before they got into actual combat with the Japanese. Photo: USMC

Shortly after the visit from the film crews, Chris Magee (left) and Bob McClurg haul a trunk to a stack of gear on Espiritu Santo, getting ready for the move to a forward operating base in the Russell Island group. It is evident from the more permanent summer camp-like qualities of the hooches, known as “Dallas Huts” and white coral streets that Espiritu Santo was not too close to the front lines. Photo via 214squadron.tumblr.com

The Turtle Bay fighter airfield on Espiritu Santo island where VMF-214 began their legendary ascent to become the most successful Marine fighter squadron of the war. There were a number of bomber and fighter strips on Espiritu Santo—the Turtle Bay strip, built in just 20 days in July 1942, was the first. Within a relatively short period of time “Santo” was developed to host five fighter and bomber airfields, a seaplane base, three hospitals, 10 small camps and 32 miles of paved road. The protected waters of Segond Canal (channel) provided anchorage for close to 100 ships and just across the channel, Aore Island was developed into a central military recreation facility featuring, among other things, more than 30 cinemas! Photo and information via SantoTravel

The new pilots of VMF-214 hanging out at the beach on Espiritu Santo, or perhaps at the Aore Island Fleet Recreation Center a few kilometres from Turtle Bay. Chris Magee stands at left. Photo via 214squadron.tumblr.com

The unit packed up what Corsairs they could muster and moved northwest along the edge of the Coral Sea to Guadalcanal and then a short hop further northwest to the Russell Islands, there to ready for combat and build a working squadron. It was from here that finally, after nearly 44 months of trying, Chris Magee rose from the recently completed coral dust runway on the island of Banika along with 19 other Black Sheep Corsairs on his very first combat mission, escorting 150 dive and torpedo bombers attacking Japanese bases in Bougainville. During this mission, the new pilots of VMF-214 shot down 11 with eight “probables”. It was an auspicious start to spectacular record by a legendary squadron. Magee and 214 left the Russells the very next day after just this one mission, moving even closer to the enemy at a crude forward base called Munda on the island of New Georgia.

Munda airfield on New Georgia—looking to the east. This photo was taken in 1944, after the Marines and others had moved on, largely abandoning the airfield. Photo: asisbiz.com

Without getting into a full accounting of VMF-214’s experiences during two six-week combat tours, Magee’s personal record would top out at nine combat victories, making him the second highest scoring ace among the Black Sheep after Pappy Boyington’s incredible 26 combat victories (officially tied with Eddie Rickenbaker’s 26 from the First World War—though Boyington claimed 28 including the six he destroyed while with the Flying Tigers in China). Even though they were in existence for just four months, the squadron was one of the most aggressive, well-led and successful units in the south Pacific during the Second World War. Operating from rough forward bases like Munda and more established airfields like those at Banika, Espiritu Santo and Vella Lavella, the Black Sheep took the fight directly to the enemy through the “Slot” (New Georgia Sound) to the Japanese bases at Ballalae, Kahili, Kolombangara, Kara and the mythic Japanese mega-base at Rabaul. Their successes were much publicized, thanks mainly to the reputation of Greg Boyington and the efforts of the squadron’s much-loved Intelligence Officer Frank Walton who went out of his way to tell the story of this remarkable unit to Americans back home. Of the 28 founding members of the Black Sheep, 3 had been trained by the Royal Canadian Air Force—Chris Magee, Bill “Junior” Heier and Don “Deejay” Moore.

Among the many colourful and aggressive fighter pilots who made up VMF-214, perhaps the most remarkable was Chris Magee, unique among the Black Sheep. An intelligent, even cerebral man who liked to work out with his weights, Magee began to dress differently from the rest. His Don Ameche mustache would eventually grow to a decidedly un-Marine-like and bohemian goatee and he was never seen without his signature blue bandit-style bandana either tied around his neck or worn do-rag style over his head in the extreme heat and dust of the coral airfields. He also scrounged up a pair of comfortable bowling shoes (Walton had mentioned tennis shoes in his book, but Reed claims they were bowling shoes) from the personal effects of another Marine pilot who was killed in action and took to wearing them for flying.

Chris Magee poses with the sign for the open-air chapel at Vella Lavella. Maravari is a spot on the southeast coast of Vella Lavella Island in the Solomons where, on 19 December 1943, Americans and New Zealanders dedicated a war cemetery for those who died taking the island from the Japanese. Perhaps this photo dates to this event, which was during the second combat tour for the Black Sheep. Photo via 214squadron.tumblr.com

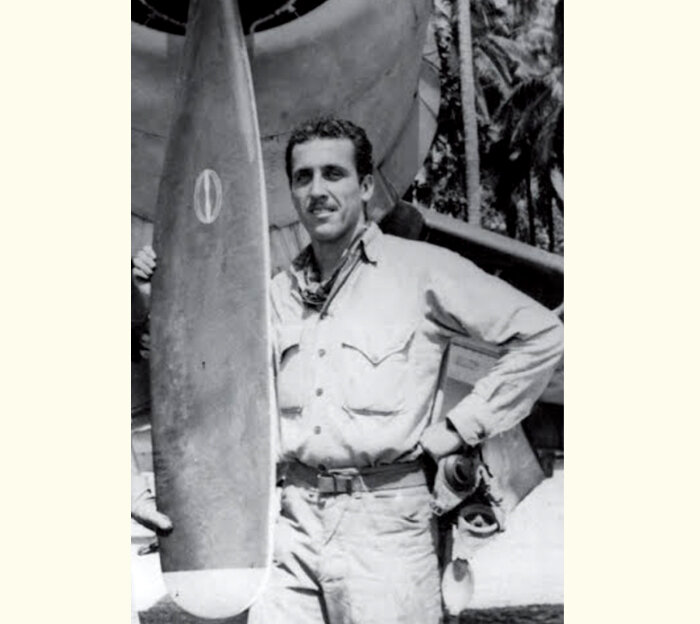

When compiling this story about Magee, it took many weeks of searching the web for images of him and his activities. As with many of these stories, I make a point of including every photo that I come across, even though it may not reveal that much about his story. I do this so that others who, in the future, are searching for images and information about my subject (in this case Magee) may have a much easier time. This photo of Chris Magee standing next to the blade of a Corsair’s Hamilton Standard propeller does not tell us much, but it adds to the total picture. I believe it to be possibly from his first combat tour as the condition of his clothing looks better. He is wearing, as always, his blue bandana knotted around his neck.

But Magee backed up his non-conformist idiosyncrasies with extraordinary competence as a fighter pilot. He was considered the best natural fighter pilot on the squadron, capable of wringing performance from the Corsair that others could not. Spoken of as “Maggie” by his comrades, he earned himself another sobriquet for his aggressive behaviour in the air and unorthodox ways on the ground—“Wildman”. Author Stephen Sherman at acepilots.com explains the action that earned Magee his Wildman name: “In later years, Chris Magee’s wartime reputation built him up into a wild man, a bearded, bandana-wearing, grenade-tossing eccentric. The stories have some basis in fact, but actually Magee was a fine pilot, the second-highest scoring VMF-214 ace, credited with downing nine Japanese planes, and winner of the Navy Cross. The grenade-throwing legends originated one day in September 1943 when the Black Sheep flew a barge-busting mission. Over Choiseul, they found a 70-foot junk. As the Corsairs swarmed over it, Magee pulled out his unauthorized grenade. He struggled mightily to pull the pin, almost breaking his teeth, eventually freeing it on the second pass. He tossed it overboard, and it somehow landed on the junk. The grenade exploded as the Corsairs raked the junk with .50 caliber machine gun fire. They left it burning and headed home. Trying to land, Magee earned his nickname “Wild Man” when he calmly brought his Corsair in for a dead-stick landing, blowing down his wheels with the emergency CO2 bottle just over the runway. Hours later, he was back in the air, on another combat mission.”

When Frank Walton summed of Chris Magee’s personality in Once They Were Eagles, you could read between the lines the respect, the head-scratching and the love that the Black Sheep had for Wildman Magee: “Chris “Wildman” Magee or “Maggie” Magee was our free spirit. He usually carried with him some thick tome on witchcraft or philosophy. He refuses to wear boots; instead he wore tennis shoes when he was flying. Utterly fearless, he usually took along a lapful of hand grenades, which he tossed over the side at various Japanese installations as he flew at hair-raisingly low levels. He always, and I mean always, wore blue nylon bathing trunks—we wondered if he ever took them off. A physical culture faddist, he could be seen in his spare time working out with his barbell, a blue kerchief tied on his head and his muscular body glistening in the sun. … … No one, no one, messed with Maggie.”

A rare original colour photograph of a VMF-214 Corsair being serviced at Vella Lavella’s Barakoma Airfield. Note the condition of the paint on this aircraft which really can’t be much older than six months, maybe less. The extreme heat, unrelenting ultraviolet rays and coral dust played havoc with paint, fabric coverings and mechanical systems.

Magee’s superior fighting skills and his fearlessness in the air earned him many decorations including the Navy Cross, Bronze Star for Valour, numerous Battle Stars and Marine Corps Achievement Medals as well as two Purple Hearts. The citation that accompanied the award of his Navy Cross (an American award for valour second only to the Congressional Medal of Honor) reads in part: “for extraordinary heroism as a Pilot of a Fighter Plane attached to Marine Fighting Squadron TWO HUNDRED FOURTEEN (VMF-214), operating against enemy Japanese forces in the Solomon Islands Area from September 12 to October 22, 1943. Displaying superb flying ability and fearless intrepidity, First Lieutenant Magee participated in numerous strike escorts, task force covers, fighter sweeps, strafing missions and patrols. As member of a division of four planes acting as task force cover on September 18, he daringly maneuvered his craft against thirty enemy dive bombers with fighter escorts and, pressing home his attack with skill and determination, destroyed two dive bombers and probably a third. During two subsequent fighter sweeps over Kahili Airdrome on October 17–18, he valiantly engaged superior numbers of Japanese fighters which attempted to intercept our forces and succeeded in shooting down five Zeros. The following day, volunteering to strafe Kara Airfield, Bougainville Island, he dived with one other plane through intense antiaircraft fire to a 40-foot level in a strafing run, leaving eight enemy aircraft blazing. First Lieutenant Magee’s brilliant airmanship and indomitable fighting spirit contributed to the success of many vital missions and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

A powerful portrait of Chris Magee, from December 1943, dramatically posed against the white star on his Corsair, possibly at the time of the award of his Navy Cross. The mimeographed caption (designed to help newspapers in Chicago and elsewhere by having the caption ready to go) on the back of this photo reads: “Dashing through a heavy barrage of ack-ack fire, First Lieutenant Christopher L. Magee, a former Royal Canadian Air Force flier and now a Marine fighter pilot, shot down two Japanese dive bombers on September 18 over Vella Lavella in the Northern Solomon Islands. Lieutenant Magee ignored the heavy firing which was slashing through his wings, and continued his dive to knock down the two enemy planes. Lieutenant Magee, son of Mr. and Mrs. Fred Magee, 919 East 50th Street, Chicago, Illinois, enlisted in the Navy after being transferred from the R.C.A.F. on May 8, 1942 and won his Marine wings December 15 of the same year. A graduate of Mount Carmel High School in June 1935, he later attended the University of Chicago where he played freshman year varsity football”. It is interesting to note that Magee is not wearing his otherwise constant blue bandana/kerchief, perhaps at the request of the Marine Corps photographer or public relations specialist. Photo: USMC

The Black Sheep were as tight a fighting unit as there ever was in the South Pacific War, and each officer regarded the others with great admiration and mutual respect, but there seems to have been a special love for Magee, partly for his free-spirited ways and partly for his formidable skills in the art they all practiced—the killing of Japanese with a Corsair. Walton writes in Once They Were Eagles, “On the ground, Magee was quiet, reserved; in the air he was a junior addition of Boyington, a wild man, man-handling his plane like a cowboy bulldogging a steer. But he could fly with a delicate touch, too.” Commenting on Magee landing his damaged Corsair after the incident for which he was awarded the Navy Cross, Walton states: “He nursed his crippled Corsair into the groves [palm groves—Ed], eased down carefully as though he were handling a crate of eggs, and then rolled free. As he flashed by us, we could see that one tire was flat, and jagged tears showed in his tail, fuselage and wings. The actual count was 30 bullet holes” and then “Three days later his engine was hit while he was strafing Japanese barges and quit as he flew parallel to our field. Instead of bailing out and letting the plane go into the water, he brought it in.”

Photos of the Black Sheep and Chris Magee during their two combat tours:

In late September of 1943, George Weller, a war correspondent for the Chicago Daily News, landed at Munda when bad weather prevented his transport aircraft from its intended destination at General McArthur’s headquarters in Australia. On finding out from Frank Walton, the squadron’s Intelligence Officer that there were several Corsair pilots from the Windy City on squadron, he asked Walton if he might interview them. The three (left to right), Lieutenants Bruce Matheson, Jim Hill and Chris Magee pose happily with one of the squadron’s Corsairs. It is possible that this photo was taken at the time of Weller’s stories. Photo: Frank Walton Collection, Colourization by We, the People Restoration and Colorization

Taken around the beginning of October 1943, this photo shows a very tired and war weary Black Sheep squadron in the Russell Island group. They have just lost one fellow pilot, while four others are MIA or recovering from wounds in hospital. Back Row, from left: John Begert, Bob Bragdon, Don Fisher, Bruce Matheson, Jim Hill, and George Ashmun. Third Row, from left: Chris Magee, Don Moore, Hank Bourgeois, Burney Tucker, Warren Emrich, and John Bolt. Second Row, from left: Paul Mullen, Bill Heier, Virgil Ray, Ed Harper, Bob McClurg, and Sandy Sims. Front row, from left: Bill Case, Frank Walton, Stan Bailey, Greg Boyington, Jim Reames (the flight surgeon), and Ed Olander. Photo: Frank Walton Collection, Colourization by We, the People Restoration and Colorization

A close-up of the men in the previous photo shows no real smiles among the men, and even a look of frustration for having to pose yet again for another PR photo. Magee at left in third row, Frank Walton, the future author of Once They Were Eagles in front with ball cap. Photo: Frank Walton Collection, Colourization by We, the People Restoration and Colorization

During their first combat tour, while on the island of Vella Lavella, the Black Sheep’s Intelligence Officer Frank Walton wrote to the Commissioner of Baseball with a proposition. The Black Sheep, said Walton, were in dire need of sun-shading ball caps due to the humid weather which quickly destroyed their military-issue caps. He promised that his squadron’s pilots would shoot down a Japanese aircraft for each cap sent to them. Only the St. Louis Cardinal organization of the National League responded, sending dozens of caps, and getting lots of PR points in return. Here, Major Greg “Pappy” Boyington (right) pretends to take a stack of Cardinals caps from Chris Magee who accepts a fan of Imperial Japanese Navy “kill marking” decals in return—a staged photo if there ever was one. Both pilots are slick with sweat in the super-heated and humid weather of a Solomon Islands summer. Photo: Frank Walton Collection, Colourization by We, the People Restoration and Colorization

On the palm-covered island of Vella Lavella, pilots and officers of VMF-214 Black Sheep pose for a public relations photograph, each wearing a newly-acquired ball cap from the St. Louis Cardinals. In the front row of the lower photo, each of the squadron’s aces or “sluggers” also holds a baseball bat. Front row with bats (Left to right): Chris “Wildman” Magee, Bob McClurg, Bob “Moon” Mullen, Greg “Pappy” Boyington, John “Blot” Bolt and Don “Mo” Fisher. On the wings: (Left to right): Sanders “Sandy” Sims, George Ashmun, Bruce “Mat” Matheson, Jim Hill, Ed “Oli” Olander, Bob Bragdon, Frank “Waldo” Walton, Ed “Harpo” Harper, Warren Emrich, Bill “Junior” Heier, Burney Tucker, Don Moore, Jim Reames, and Denmark “Quill Skull” Groover. I believe this was taken just before or immediately after their R&R at Sydney, Australia at the end of October 1943, for none of the 21 new pilots who joined them on Espiritu Santo on 19 November are in the photograph, nor are the two aces Bill Case and Hank McCartney, who left the squadron after the first tour. There are websites that claim that this photo was taken in late December of 1943, but I doubt they would have excluded so many pilots from the photograph. Photos: Top: donholloway.com; Bottom: Pinterest

Following their first 6-week combat tour in the Solomons, pilots of the Black Sheep squadron were given a much-needed and much-anticipated week of R&R in Sydney, Australia (“exclusive of travel time”). Here, Lieutenants Chris Magee (top) and Bill Case try to rest above stowed cargo aboard a US Navy Douglas RD4 (C-47 Dakota), likely en route to Sydney as the two are wearing ties and pressed shirts in anticipation of their holiday.

At the start of their Second Tour in mid-November 1943, the 21 remaining Black Sheep pilots and officers of VMF-214 from the first tour were joined by 21 new pilots on Espiritu Santo and then moved to Vella Lavella where they were based for the entirety of the second tour. Photo: Frank Walton Collection, Colourization by We, the People Restoration and Colorization

Chris Magee with his omnipresent blue bandana tied around his neck is centre of the middle row. Boyington is third from right in front. Photo: Frank Walton Collection, Colourization by We, the People Restoration and Colorization

In a quiet spell during their second combat tour, a small group of pilots and officers outside the operations tent at Vella Lavella offer no hint of the stresses of continuous combat flying. Chris Magee stands second from right. His upper body shows the effects of his weight-lifting and body-building. Squatting (left to right): Bruce Matheson, Burney Tucker and Harry Johnson. Sitting at left: Perry Lane. Standing: Denmark Groover, Ed Olander, Bob McClurg, Jim Reames (ducking), Glen Bowers, Fred Losch, Ned Corman, Jim Hill, Bill Hobbs, Magee and Ed Harper. Photo via 214squadron.tumblr.com

Vella Lavella airfield, 10 December 1943. Visible are U.S. Marine Corps Vought F4U-1 Corsairs, Grumman F6F-3 Hellcats, a Douglas SBD Dauntless, and RNZAF Curtiss Kittyhawks on the primitive runway which was seized in the summer of 1943 and served as a base of operations to support landings by Allied forces in the Treasury Islands and at Cape Torokina, Bougainville. The swift advance of Allied forces in the South Pacific soon bypassed Vella Lavella and the airfield ceased operations in September 1944, less than a year after the first aircraft arrived. Photo/caption: Wikipedia

A poor photo of a wary, Nosferatu-like Chris Magee in the cockpit of a Chance Vought Corsair (833) in one of the South Pacific bases VMF-214 operated from—Vella Lavella, Mundi or perhaps Espiritu Santo. A Corsair, painted in the same markings as 833 now hangs from the ceiling of the National WWII Museum in New Orleans, Louisiana. Photo: acesofww2.com

Thanks to historic photo colourist Craig Kelsay of We, the People Restoration and Colorization, we have a more revealing look at a series of public relations photos taken of Black Sheep pilots, many from the second combat tour. Here, a number of Black Sheep aces are grouped together, likely later in VMF-214’s combat history and possibly after their commander Greg Boyington’s capture (it seems likely that he would have been in this shot with the other aces had he been there). As the photographer snaps the picture, the six pilots turn toward someone off camera and laugh. Left to right: Back row: Lieutenant Pail “Moon” Mullen (6.5 victories), Lieutenant John Bolt (6 victories), Lieutenant Bob McClurg (7 victories). Front: Lieutenant Edwin Olander (5 victories), Chris “Wildman” Magee (9 victories), Lieutenant Donald H. “Mo” Fisher (6 victories). Photo: Frank Walton Collection, Colourization by We, the People Restoration and Colorization

A close-up of the previous photo provides us an intimate look at the man known as “Wildman” to his squadron mates. We see Chris’ signature blue bandana tied around his neck, a fashion accessory he was never seen without—often tied around his head in do-rag fashion. Photo: Frank Walton Collection, Colourization by We, the People Restoration and Colorization

In late December of 1943, while Chris and the rest of the Black Sheep were taking it to the Japanese in the South Pacific, his cousin’s poem, High Flight, was already a major hit among Allied pilots and their families back home. On December 21st, Orson Wells, in his signature basso voice, recited High Flight on an episode of Command Performance, a radio show broadcast on the Armed Forces Radio Network over the shortwave network. I like to think that Chris Magee had tuned in that night on a remote island in the Pacific and somehow made the connection.

The Black Sheep story may have been a longer one, save for one event. On 3 January 1944, as the last days of their second combat tour were winding down, their beloved commander Major Greg Boyington was himself shot down. The pilots of the unit, who were so tightly bound to each other and to their charismatic leader, were devastated. They took their frustrations out on the Japanese for the rest of their tour, raging “like wild men, up and down the coasts of New Ireland and New Britain, shooting up barges, gun positions, buildings, bivouac areas; strafing airfields; killing Nip troops; cutting up supply dumps, trucks, small boats”. At the close of the tour, the 13 Black Sheep who had three combat tours under their belts were shipped home, and those, like Magee, who had just two combat tours, wanted to stay together along with a new baker’s dozen pilots. They all felt that the aggressive spirit of the remaining core of experienced pilots under the name Black Sheep would ensure that the squadron would remain the best unit in the South Pacific. Unfortunately it was not to be, and the last of Boyington’s Black Sheep were assigned to different squadrons in the theatre, with a number, including Chris Magee, going to VMF-211(The Wake Island Avengers), another Corsair squadron soon to be based on recently-captured Green Island… an atoll now known as Nissan Island.

Magee’s third and final South Pacific combat tour was with VMF-211, the Wake Island Avengers, on Green Island between Bougainville and New Ireland. This and the following photograph may depict Magee and three of his former Black Sheep squadron mates there in early 1944 hamming it up with “pilot hands”. Magee, at right wears his signature blue bandana and now, a non-regulation goatee and mustache. Judging by the laughing facial expressions and the focus on Magee, he is the instigator of this set-up. Left to right: Lieutenant Robert W. “Bob” McClurg (7 victories), Lieutenant Jim Hill (1 victory), Lieutenant Junior Heier (4 victories) and Chris Magee. Photo via 214squadron.tumblr.com

Another photo, taken at the same time and in front of the same VMF-211 aircraft as the previous shot, includes only Magee, Junior Heier and Jim Hill. Not sure what the connection is between these three that interested the public relations photographer, except that they were all former Black Sheep. Magee shows his non-conformist ways with his goatee, blue bandana and bowling shoes. Photo via 214squadron.tumblr.com

Chris Magee hams it up with a fellow pilot (possibly Jim Hill or Warren T. Emrich) in the chow line somewhere in the Solomons. It is clear from most of the photos of Magee that he was somehow different—the way he looked, the way he carried himself and the way he acted displayed a certain confidence and self-determination. It appears that in this photo, Magee is sporting the same goatee as seen in the previous image, leading me to believe that this photo also dates to his final tour with VMF-211. Photo via 214squadron.tumblr.com

Despite the fact that they were closer than ever before to Rabaul, the presence of the Japanese Navy in the air and on the seas was negligible. Rabaul itself was cut off and its importance neutralized. The Royal New Zealand Air Force and United States Marine Corps Corsair fighter squadrons and Ventura bomber units based at Green Island pretty well owned the airspace throughout New Ireland. Magee’s six-week combat tour resulted in not a single engagement with enemy aircraft. They were engaged in fruitless patrols, escort duty for bombing raids that were not met with defensive fighters, and a few vehicle strafing missions. Needless to say, Chris Magee, the ultimate combat fighter pilot, was frustrated with the inaction and longed to get back into the fight.

His third six-week combat tour was finished in late April 1944. Though there the war was still more than a year from its fiery end, it was Magee’s lot to be shipped home, there to train for other duties. For a warrior aviator like Magee, this was anathema. His immediate goal was to get back into the war as soon as possible. After catching up with family and friends, Chris travelled in August of 1944 to his new assignment at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina. He was assigned to another squadron, this one VMF-911, a unit just reforming. Flying was not consistent—usually SNJs and some Corsair hops. The most important event during his stay at Cherry Point, however, was the meeting and courting of Navy nurse Molly Cleary. Like so many relationships in those days, the courtship was rapid and within a few weeks they were married in October of 1944, with Black Sheep squadron mate Fred Losch standing in as best man.

When Magee returned to the United States after his third and last combat tour (with VMF-211), he found himself at Cherry Point, North Carolina, where he met and married his wife—a Navy nurse by the name of Mary Victoria “Molly” Cleary. Prior to Magee’s return to Miramar, California and eventual transport back to the Pacific with VMF-911, his first child was born—Christopher Lyman Magee Jr., who one day would become his father’s biographer.

As 1945 rolled around, Chris must have been very anxious to return to the war. The Nazis were on the ropes and just a few months from the end they deserved. The Japanese were being burned out of Iwo Jima and in a few weeks they would feel the full weight of the Marine Corps, Army and Navy on one of their main outlier islands—Okinawa. The war could go on indefinitely, or it could be over in a flash of white nuclear heat. Time spent at Air Ordnance School in late 1944 with few opportunities to fly must have burned inside his warrior soul. He had proven himself in battle in every way, but he wanted to return to combat squadron life. In February, things began to get better with the squadron’s transition to the new Grumman F7F Tigercat twin-engine fighter. The pilots were excited about its potential and anxious to take them to the South Pacific for the final assault on Japan. They would train on the new Tigercats throughout the summer, transferring to El Centro, California mid-summer for final gunnery testing in extreme heat conditions.

Following his three combat tours in the South Pacific (two with VMF-214 and one with VMF-211), he was sent stateside to Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point in South Carolina, there to join the Devilcats of VMF-911, the second Marine fighter squadron to be equipped with twin-engine fighters after VMF(N)-531, a night fighter unit. Here we see newly-promoted Captain Chris Magee standing in front of the starboard engine of a VMF-911 Grumman Tigercat on 1 June 1945 at Kinston Auxiliary Airfield. Photo: navypilotoverseas.wordpress.com

A photo of VMF-911 pilots waiting to take delivery of their new Grumman F7F Tigercats in February of 1945. I am not 100% certain, but the pilot standing at left in the stained flight suit looks like very much Chris Magee. If you look at the profile of Magee in the next photograph, you might agree with me. Regardless, he carries himself with a loose kind of composure befitting a pilot and ace of his experience. Photo: navypilotoverseas.wordpress.com

In this photo, Magee (second from left), at head of line of VMF-911 pilots, looks rather bemused by the set-up. I’m not exactly certain what this photograph was supposed to convey, but it’s clear Magee thinks it was all a little awkward. Photo: navypilotoverseas.wordpress.com

While Chris geared up for the move to California, Molly took the train to New York to stay with her parents and await the birth of their first child, due in the middle of that summer. Just a few days before Chris and the rest of VMF-911 left for the West Coast from Cherry Point, he got word that his son, Christopher Lyman Magee was born in a New York hospital. These days, a pilot would be given leave to attend the birth and stay behind while the squadron moved, but there was a war on and there is no doubt that Chris Magee was anxious to get back in it. By the end of August, they were ready to deploy to Japanese waters, but their sailing date was cancelled when the Japanese surrendered. Chris Magee’s war was over. Most men and women in the armed forces of the Allies were overjoyed to be going home, to put the sundry hells and misfortunes of a world war behind them, to know they had survived. But for a fraction of these soldiers, marines, airmen and sailors, the end of the war meant the end of belonging. These were the warrior spirits, the men who lived to test their metal and risk their lives against a strong enemy every day. Chris Magee was among their ranks.

Not too long after the end of the war, while Chris was still with VMF-911, he got some good news about the commander of his old Black Sheep squadron—Greg Boyington had been confirmed still alive and freed from a Japanese POW camp and was being flown home to San Francisco. Twenty-one of the Black Sheep pilots were still stationed somewhere on the West Coast and they were rounded up by the Marine Corps to form a welcoming party for Boyington’s triumphant arrival at Naval Air Station Alameda in Oakland. And what a party it was—covered by a large contingent of the press corps including a reporter and photographer from LIFE magazine. It would be the last high point in Chris Magee’s military career. Not long after Boyington’s homecoming bash, Chris Magee opted to resign from the Marine Corps rather than fly with the squadron to Okinawa. He didn’t just want to fly fighter aircraft, he wanted to fight with them in real combat against real enemies. Peacetime flying held no interest for him.

A photo of sailors and VMF-214 pilots overwhelmed with joy and hoisting Boyington to their shoulders after he got off the airplane at NAS Alameda. Chris Magee, now a Captain, can be seen at left. Photo: LIFE Magazine

When Major Greg “Pappy” Boyington returned to San Francisco from a Japanese POW camp in late 1945, he was given a promotion and was welcomed by both the media and any former Black Sheep that were still serving in California, which turned out to be many. Here, after being greeted at the airfield, Boyington holds court in the bar at San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel, regaling his adoring pilots, including Chris Magee at far left. Boyington was universally admired by his pilots, though, as a Black Sheep Pilot said, “His behaviour on the ground was not always exemplary”. In Frank Walton’s Once they Were Eagles, Black Sheep pilots said, almost to a man, that Boyington was “a tremendous combat leader”, “a dynamic leader” and that the unit was a “free-thinking, free-speaking” unit. With fellow Black Sheep aces Magee, Paul Mullen, Ed Olander and Bill Case with him at the bar, this seems a staged photo for the LIFE Magazine photographer. Photo: LIFE Magazine via Frank Walton Collection, Colourization by We, the People Restoration and Colorization

Chris Magee (top left corner) looks on as fellow Black Sheep ace Bill Case entertains the boys at the bar of the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco. Photo: LIFE Magazine

During his welcome home party at the St. Francis hotel in San Francisco in September of 1945, Greg “Pappy” Boyington hears a funny story from the squadron’s Chaplin, Padre Paetznick, of the tearful ceremony he conducted at Vella Lavella for their leader, who they thought might have been dead at the time. Between them in the background, Captain Chris Magee looks introspective and strangely subdued. Photo: LIFE Magazine

As he resettled with Molly and Chris Jr. in Chicago, Magee took his time to consider what to do next. He turned down several offers to join airlines, knowing full well that towing a company line would never be something he could do for long and besides, he was a fighter pilot, not a transport pilot. He brought his growing family to New York, where he took a low-paying job on a freighter travelling to and from Europe delivering war brides to America just so he could witness the devastation that had happened there. He did this for the spring and early summer of 1946 and got a taste for the Black Market—bringing items to Europe that were in short supply there—easily transported items like lipstick. While he was sailing back and forth across the Atlantic, his daughter Christine was born.