FLYING THE WESTLAND LYSANDER

I know of no other pilot’s seat in all of aviation like the one in a Lysander. It’s a throne. It’s way up high, and climbing up there is like ascending the ratlines of a square-rigged ship. Your feet slip into toeholds here and there, you swing from various struts, and eventually, when you reach the summit, you stand on the cockpit sill and can view the airport from a truly lofty perch.

Once in the seat, you can further attain the utmost elevation by winding on an adjustment wheel by your right leg. This cranks the seat up so high that you can hardly see the tops of the round dials on the panel. You can actually see over the nose of the 860 hp Bristol Mercury XX radial engine, and it overlooks everything on the field.

Of course, the purpose of all this elevation was to allow an almost perfect view of the battlefield. In 1937, it was assumed that the Lysander would be up there on the front lines, spotting for the artillery and discovering where the enemy was hiding. That was before May 1940 in France, when a horrific loss rate made it clear that complete air superiority was essential to the Lysander’s survival. Later, the aeroplane [it is so utterly British that it must be spelled “aeroplane”, not “airplane”], had other roles to play, like dropping secret agents, weapons and radio equipment into small pastures in Occupied France in the dead of the night.

Mike Potter bought Lysander CF-VZZ from a Saskatchewan farm. It had been built originally at Malton, Ontario—where the Avro Arrow would eventually fly, then be scrapped—and was flown by the RCAF as a target tug and liaison aircraft. Used briefly post-war as a crop-duster, it had languished for decades, until being largely restored by Saskatchewan collection and warbird restorer Harry Whereatt, the man who also began the restoration on our Hawker Hurricane XII. Vintage Wings of Canada assembled a team of volunteers and through three years of steady work, had it ready for a first flight in 2010.

Mike usually flies the fighters, but received a checkout in the Lysander in July 2014, and enjoyed it so much that he sent me an email: “Dave, as Manager of Restorations, you should fly this machine—it’ll help you understand the complexities of aircraft of this era.” I replied immediately, that yes, his logic was impeccable!

House of Dreams Come True—Dave Hadfield photographs his other radial-engined high wing vintage aircraft, the Fairchild 24W Argus as it communes with its new big brother, the Westland Lysander at the Vintage Wings hangar. Photo: Dave Hadfield

Veteran warbird pilot Dave Hadfield sits in his “throne for a day”—the lofty pilot’s seat of the Vintage Wings of Canada Westland Lysander—following his first flight in the rare aircraft. Photo via Dave Hadfield

Related Stories

Click on image

The Vintage Wings Lysander is painted in overall silver to represent National Steel Car-built Lysander No. 416, the first built by the company in 1939. Photo via the Tucker Harris Collection

The Vintage Wings of Canada Lysander was purchased by collector and founder Michael Potter from Saskatchewan collector and restorer Harry Whereatt. Here we see his Lysander nearing completion in 1993. Whereatt chose to paint the Lysander in the famous and ultra-bold yellow and black scheme that was employed by target tugs of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Known as the “Oxydol” scheme for its resemblance to the laundry soap flakes packaging of the day, the markings were meant to make the aircraft as visible as possible to gunnery students. Photo via Bill Ewing

Harry Whereatt never flew his Lysander, but he did fire it up at aviation events. Here we see the first engine run in July 1996. With Harry at the controls, the Bristol Mercury engine coughs to life with a farm pickup truck supplying the ground power to crank the engine. Despite the successful engine start, the Lysander never flew for Harry—qualified Lysander pilots being in short supply in Southern Saskatchewan at the time. Photo via Bill Ewing

The Lysander is an oddball, although I mean that in the most affectionate way. For example, the pilot has absolutely no control over when the slats and flaps deploy or retract. No lever, no valve, no switch. There are corners of the envelope where there is not enough elevator authority to stop a pitch-up, or make it flare for landing. Thus, it is not an aeroplane to fire up lightly. A thorough ground school and flight briefing is essential.

My coach for this was John Aitken: Senior Pilot at Vintage Wings, winner of the McKee Trophy*, retired Chief Pilot at the National Research Council of Canada’s Flight Research Laboratory, Spitfire and Mustang pilot, Aviator-Emeritus. I met him in the classroom one Friday and spent the afternoon reviewing his Lysander Course—which by the way will probably be taught in the winter of 2014–15 as part of our very popular “Warbird U” series. This was a very polished and professional PowerPoint-based presentation that covered all aspects of the airframe and systems. Later we moved to handling and the checklist, then normal operations and emergencies.

They don’t make ’em any better than this—John Aitken, Aviator-Emeritus and Dave Hadfield’s mentor for his first flight in the Lysander. Photo: Dave Hadfield

There are 24 complete Lysanders in the world today, most of which at one time were owned by the RCAF. Only three are flying examples—all built in Canada, two of which are in Ontario, the other in the Shuttleworth Collection at Old Warden, Cambridgeshire. This wartime photo of Lysander with RCAF serial 1589 shows the typical RAF livery of the day. After the battle of France, Lysanders were being shipped to Canada to be used for training purposes and to keep them safe from destruction by German fighters. In the 1960s, 1589 was partially restored in Canada then gifted to the Indian Air Force in the early 1970s. The aircraft today can be seen at the Indian Air Force Museum. Photo: RAF

In an exercise of army cooperation at RAF Odiham, Lysander pilots of No. 400 Squadron RCAF rush to climb into the cockpits of their Lysanders, having just received their operational orders from an Army Liaison Officer standing at the desk at left. In the combat arena, the Lysander proved to be capable, but also vulnerable, resulting in a quick withdrawal from front line service. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Four seemingly brand new Lysanders of the Royal Air Force’s 16 Squadron form up smartly over English countryside—likely in 1938 or 39, before the beginning of the Phoney War and the Battle of France. Four regular squadrons, including 16 Squadron, were equipped with Lysanders and accompanied the British Expeditionary Force to France in October 1939, and were joined by a further squadron early in 1940. Following the German invasion of France and the low countries on 10 May 1940, the Lysanders were put into action as spotters and light bombers. In spite of occasional victories against German aircraft, they made very easy targets for the Luftwaffe even when escorted by Hurricanes. The squadron continued using the Lysander on air sea rescue duty until April of 1942. Photo: RAF

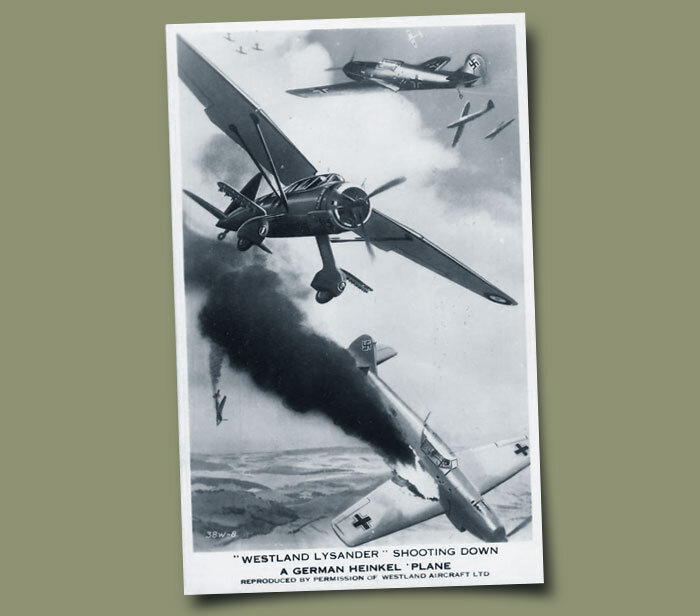

A rather fanciful depiction from the start of the war shows a Lysander tearing into a formation of “Heinkel Planes” and sending a couple to their demises. The image is wrong on two accounts. The aircraft burning in this scene is a Messerschmitt Bf-109, not a Heinkel, and the Lysander did not stand a chance against such a powerfully armed fighter as the 109. Whatever hopes were placed on the Lysander’s performance in combat were soon dashed during the Battle of France. 118 of the 175 Lysanders deployed were lost in combat or on the ground.

I had read the Second World War pilot’s notes, which led me to conclude: “Man, is this thing British!” But the ground school was far more complete. The high-lift devices are an example. There are leading edge slats in two sections, inner and outer. They are of the Handley Page principle: as the aircraft slows and its angle of attack increases, lift exerted by the airfoil action of the slat is harnessed by very clever gears to deploy them forward automatically. Out they go on their own! This is similar to the A-model Tiger Moth and others as wide-ranging as the Messerschmitt Bf-109 and the Canadair F-86 Sabre VI. What is unique is that these inner slats are chain-linked to the flaps, and as the slats go out, so to do the flaps. No handle or button or lever in the cockpit whatsoever. No lock. No control of any kind.

Do we take off like a normal taildragger? (Power-up, pause, then stick-forward and raise the tail?) Nooooo... because this would reduce the angle of attack and retract some of the flaps and slats and increase your stall speed and take-off run. In the Lysander, we take off three-point! (Or very close to it.) As I say, it is unwise to just hop in a Lysander and go, assuming that unlikely event was possible.

Earlier that morning we had pre-oiled the nine-cylinder Mercury, which is necessary to avoid metal-upon-metal during start-up. The manual calls for this if the engine has been sitting for five days (bring plenty of rags, it’s a messy business). First, oil is heated in a five-gallon tank equipped with a hand-pump. Then the oil screen is removed from the lower forward section of the crankcase (accessible from the bottom of the cowl), and the oil line is connected to one of three ports located in an access door on the left side. These ports lead to the crankshaft, the supercharger, and the reduction gears. In each case, you pump until oil flows out the oil screen housing. Of course then it also flows all over the bottom of the cowl, down into the carb air intake, and onto the floor—very liberally! (We deployed a large wheeled oil-change pan.) Several gallons were used. Everyone’s hands and at least one shirt front were well lubricated.

This big brass nut must be unscrewed and the screen removed to confirm that proper pre-start lubrication has taken place. (Hint: don’t wear new clothes.) Photo: Dave Hadfield

The carb air intake—This is where the pre-flight lubrication oil emerges, and pours all over your shoes. Photo: Dave Hadfield

There is a separate lubrication schedule for the rockers in the cylinder heads. There is no pressure oil feed and they have to be greased and oiled, like a Kinner engine.

Bristol Mercury engines have a reputation for being hard to start. Ours wasn’t, although there is a “bit of a procedure.” After the pre-oil, we of course pull the engine through. This confirms we don’t have a lower cylinder full of oil. (Engines like these are made of unobtanium—we don’t want to bend a connecting-rod.) Then, walk around complete, we climb Mt. Lysander and get seated. On the panel is a big Ki-Gass** primer (it’s like a Cessna primer but with 4 times the volume). You can direct the prime to two places: the carburetor bowl or the cylinders. First you fill up the bowl. At first it feels like you’re pumping air, but using a very rapid stroke a little resistance can be felt at the end of each one. John was on the ramp watching and confirmed that fuel was dripping onto the ground – bowl full. It took about 60 fast strokes. Then we turn the lever and direct six good hard pumps to the cylinders.

The selector on the right routes fuel to either the carburetor bowl or the cylinders for starting with the Ki-Gass primer on the left. Photo: Dave Hadfield

The boost-coil and start buttons are pressed simultaneously, the prop turns, and after three blades, the mags go to “ON”. With luck, it starts immediately—ours did.

The Mercury is known for a few bad habits such as carb ice, “rich cut” and backfires after start and while taxiing. Paul Tremblay, our Director of Maintenance, had adjusted the idle mixture to max rich. This, plus very slow forward movement of the throttle resulted in smooth engine running on the ground, and no backfires. Leaving the Carb Heat to “Hot” helps with this by richening the mixture. And it has the lowest idle RPM of any aircraft engine I’ve ever seen. It will run at 300 engine rpm, and it’s a geared engine, so the prop is about 40% slower. You can almost count the blades going by, like a windmill in a gentle breeze. Starting is accomplished with the prop pitch set to “Coarse”, like a Harvard. Once oil pressure is confirmed, “Fine” is selected.

Taxiing is the main gotcha with this aeroplane. It has a long wheelbase, the mains are fairly close together, and the tail is quite heavy. This means when you jab a brake, not much happens. There just isn’t much turning-moment. Of course, the brake controls are British, a lever on the spade grip of the control column, plus differential on the pedals—and it has pneumatic bladder shoe brakes. (Did I mention it was British?)

Our first sortie was in the face of rapidly advancing rain clouds, so we made it a ground mission. This is actually a very good intro to any radically new airplane—don’t go flying at all. Start it up, taxi it around, shut it down, then go home and sleep on it.

In 2010, the pneumatics gave us trouble. The engine-driven pump couldn’t keep up. Then we plumbed an electrically driven air pump into the line. Fixed! But the thing still doesn’t like to turn. It’s the geometry, not the British brakes, and from what I’ve read, pilots complained about it in the Second World War.

The tail is quite heavy. I tried the Tiger Moth trick of full rudder, forward stick, a large blast of power—ground-looping around—no result. CF-VZZ has ballast in the tail for flight controllability, but it makes the tail that much heavier on the ground, and even less likely to turn. There is no tailwheel steering of course. It’s free-castering, or such is the theory. Reality: it likes to go straight, or on its own merry way.

So, the best you can do is get up a head of steam, then apply full rudder and a large squeeze of brake, plus keep in mind where the wind is coming from. It reminded me of flying off floats or skis: sometimes it’s impossible to force the rudder up into a side wind from a standing start, and it’s better to turn the other way, 270 degrees, getting up some momentum, to achieve a 90 degree turn.

John said there are times when you can land this aeroplane, but cannot taxi it to the hangar. I concur. Rick Rickards, who flies the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum’s Lysander in Hamilton, says he uses hangars, offices, large trucks, every bit of wind-shelter he can find sometimes to get to the runway and back.

Day Two: there was a crosswind rising, but John said it was do-able, and since he was sitting in the back seat, with no controls, and me on my first flight, I was forced to believe him. (A brave man, John Aitken.)

Start-up was as before—exactly. Smooth and clean. Run-up was straightforward, although the brakes were not strong enough for the highest-power segment of the check. We trundled out to the runway, being careful to remember not to instinctively rely on toe-brakes, which don’t exist. (Lysanders trundle—that’s what they do.)

John said he found the rudder bar distracting. It’s a simple bar, World War One-style, pivoting in the middle, with footrests for each boot. He was accustomed to rudders which move fore-and-aft, and in which your heel slides on a plate, with only your toes on the pedal. This is quite different. It’s similar to the Hawker Hurricane’s arrangement. I have a few hours on our Hurri IV, thus it didn’t feel too unfamiliar.

A true, old-fashioned rudder bar, pivoting in the middle. (Note to pilot: don’t drop anything. Photo: Dave Hadfield

Grandly backtracking, surveying the world from on high, “Lord-Of-The-Manor”, we arrived at the runway end and made ready for flight. John recommended closing the side windows: “It’s noisy as hell!” The canopy arrangement works well—a sliding hood comes forward overhead and locks into the top of the windscreen, and then a slider comes up on each side and notches into place. Plus there are smaller sliders in each side window.

But here, before takeoff, we need to talk about elevator trim: there isn’t enough elevator authority to control the aeroplane is all phases of flight, and it’s not just a matter of overpowering a mis-set trim with sheer muscle. The horizontal stabilizer is on a screw-jack, and as you wind the trim wheel, its entire angle of incidence changes. You need this extra pitch authority to control the aeroplane. For example, if you are trimmed for an approach, and then must go-around and apply full power, full forward stick will not be enough to stop the aeroplane from going for the moon. You need trim as well. And here’s the thing: the trim wheel is stiff, and it takes about 20 seconds to wind it from one end to the other. Similarly, on takeoff, if you have it trimmed at the takeoff setting, and encounter a complete engine failure at 200 ft., you can get the aircraft pitched down, but you will probably not have enough authority to round-out for a landing.

So on take-off, we mis-trim, and set it halfway between the Takeoff mark and full UP. This allows us to control the airplane during takeoff, and still have a good chance of doing so if the engine quits at the wrong time. (Other Lysanders may have different trim regimes depending on their ballast and passenger loading.)

The infamous Lysander pitch trim wheel and indice. You need this plus the joystick to control the aircraft’s movements, and it takes 20 sec. to wind it from one end to the other. Photo: Dave Hadfield

Later, on approach, we remind ourselves that in the event of a go-around, we will do it in stages: power, trim, power, trim, power, trim... Speaking of power, the aeroplane has bags of it. Over 850 hp in a geared, supercharged engine turning a three-bladed prop, and we aren’t carrying any wartime loads. VZZ weighs less than a DHC-2 Beaver, with nearly twice the horsepower. The book calls for 4 1/4” of boost on takeoff. I think I got to 1 ½” and suddenly it was airborne.

And it gets airborne in nearly a three-point attitude. This is one aeroplane in which you don’t push the tail up during the takeoff roll, as stated earlier. We didn’t quite take off three-point—the slipstream is powerful and the elevator is so low that there is a ground-effect there, and it lifts the tailwheel off. But the thing magically departs planet earth and suddenly you’re 50 ft. up. To be honest, it’s not much different from a lightly-loaded Moth on a gusty day. They’ve been known to do the same thing if you don’t raise the tail. But by the time it happens on the powerful Lysander you have accelerated well above the deep-stall speed, and you’re away!

A photo of famous Lysander K6127 demonstrates the three-point takeoff attitude particular to the type. K6127 was used to explore many modifications to the Lysander including engine changes, defensive guns and was famous for being converted to the Delanne twin tail variant. Photo: RAF

The Lysander’s failure to protect itself from the enemy in the Spring of 1940 led to the development of a prototype called the Delanne Tandem Wing or Lysander P12. Westland designers worked with Frenchman Maurice Henri Delanne to develop more lift at the back of the aircraft to allow for a heavy defensive machine gun turret at the rear. Only one prototype was constructed—from test bed K6127. The large yellow P in a circle roundel on K6127 denoted a prototype. Photo: RAF

Lysander N1256, a RAF Odiham-based 225 Squadron Lysander shows the bomb racks suspended beneath winglets cantilevered off of her wheel pants. Note the wheel of a second Lysander, visible beneath the fuselage of N1256. Photo: RAF

Perhaps the best-known role for the Westland Lysander during the Second World War was its use as a “spy taxi”, an aircraft capable of flying low under the radar and delivering secret agents, weapons and radio equipment to resistance fighters in France and Belgium. The Lysander’s robust landing gear and short field landing capabilities made it perfect for the task. The Lizzie was modified somewhat for the task with the addition of a large centreline fuel tank for extra range and a quick access ladder for the fast planing and deplaning of agents. The variant was called the Lysander III SCW for Special Contract Westland. The SCW Lysanders were painted matte black overall and flew with 138 Special Duty Squadron and 161 Squadron of the RAF. In all, Lysanders transported 101 agents to and recovered 128 agents from Nazi-occupied Europe. Photo: Nigel Ish

Perhaps one of the most unsung roles that the Lysander was well suited to was that of Air Sea Rescue (ASR) operations over the English Channel, North Sea and waters surrounding Great Britain. Lysander crews would respond to an emergency call from airmen about to ditch or take to a parachute over the Channel. Their mission was to find the airmen in the sea and drop them a life raft, then vector a fast RAF patrol boat to pick them up. Fourteen squadrons and special flights were formed in England to the ASR role. Here an ASR Lysander drops a life raft from a pod slung from its wheel pant bomb rack winglet. As it falls, the raft begins to inflate. Note the defensive twin machine guns to fend off attacking fighters. Photo: RAF

Canadian-built Lysanders at a Bombing Gunnery School in Canada wear the distinctive “Oxydol” paint scheme of yellow and black diagonal stripes. The Lysander of Hamilton’s Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum flies in these very colours.

A National Steel Car–built “Oxydol” Lysander, employed as a gunnery target-towing aircraft in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Photo via Etienne du Plessis’ Flickr site

A mild swerve tells you it’s a left-foot airplane! The prop turns British, again like a Moth. In reality this makes no difference. You simply do what you have to do to eliminate yaw. But if you were accustomed to flying only North American products, it might generate a surprise.

Your hand goes instinctively to the trim wheel, winding forward madly, and you accelerate to above 110 mph for the slats and flaps to retract and so the engine will stay cool, gills fully open. (If the engine quits, you will have to ram down the nose and wind the trim madly back again to be able to flare.) Here we run into a propeller issue: this is a two-speed Rotol unit, not a constant speed. We took off in Full Fine. If we leave takeoff power on, and pitch in Fine, we can over speed the Mercury beyond its 2,650 RPM limit. So, we try to keep the RPM back to its max climb limit of 2,400 by selecting the prop to its other position—Coarse. (There is nothing in-between.) Often this occurs before we’re past the end of the runway.

After that, you’re flying! In the air it behaves like any airplane. It’s heavy in pitch, but you trim that out. The ailerons are heavy but responsive, like a Douglas DC-9. The rudder is very light. (I don’t know why this is—the aircraft does not employ an obvious aerodynamic balance on the rudder. Perhaps the placement of the rudder hinge, well aft of the leading edge, provides a scoop-effect. But it is very slight when viewed on the ground.) The top needle on the Reid-and-Sigrist Turn-And-Slip indicator wasn’t working, and thus I think I may have rattled poor John around in the back like a pea in a pod.

We didn’t have a lot of ceiling that day, thus were a bit limited in exploring the aircraft’s margins of flight. Gentle banks back and forth morphed into lazy eights and wingovers. I noticed that anytime the nose pointed well down, the stick ended up near its aft limit to arrest it. Anything more aggressive would have required trim during the manoeuvre. The Lysander is not an aerobatic king. Still, it was very enjoyable—the view is tremendous! You are out in front of the wing—you can sight down its leading edge—and can see almost vertically down if you move your head to one side. Speaking of which, when I explored sideslipping, I had the side small window open, and an enormous blast came through. I wasn’t wearing my helmet that day because of an avionics problem, just a headset and a ball cap. When the sideslip happened, air pounded through the side window, struck my face from a low angle, caught the bill of my hat, and lifted that plus my headset off the top of my head. Very startling! And very, very noisy all of a sudden!

The Vintage Wings of Canada Lysander in flight over her home in Gatineau, Québec. The aircraft is dedicated to Sergeant Cliff Stewart, a Canadian Army soldier who trained as a secret agent at the infamous Camp X on the shores of Lake Ontario. Stewart is the only non-airman to which a Vintage Wings aircraft is dedicated. Stewart once related that he once found himself smoking a cigarette while sitting on a case of dynamite in the back of Lysander, flying at night, low level, deep into Nazi-occupied France... not knowing if it would be the Gestapo who would greet him on the ground. With just a hint of irony, he also said: “If I had known smoking was bad for my health, I would never have started!” Photo: Peter Handley, Vintage Wings of Canada

We don’t stall the Lysander. It’s prohibited according to the Pilot’s Notes. What would happen is that full nose-up trim would be required to gain the elevator authority for a deep stall, combined with hi-power prop blast to aid elevator effectiveness. Then, if the engine quit, you would have to wind the trim fully nose down and wait for a considerable period before enough elevator authority would return to un-stall and recover. A great deal of altitude would be lost. Same with spins—we don’t do them. The Lysander is not a trainer.

People have always tended to lump the Lysander and the Fiesler Storch in the same category. This is nonsense. The Lysander is designed to go FAST as well as slow. Once the wings are cleaned up and gills closed, those 850 horses can be gainfully employed, and the aircraft can easily do 180 mph or more. Try that in a Storch! Vne† in a dive is 300 mph! The Mercury can be made to burn about 30 gal/hr with the mixture in “weak” and power at 2,200 rpm. This gives 140mph IAS (Indicated Air Speed). The single tank (just behind the pilot) contains about 95 Imp. gal.

It’s hot in the front seat. The oil tank is behind the instruments, on your side of the firewall. There are 2 oil coolers ahead and below your feet (for those ultra-slow, high-power approaches). On a hot day you slowly cook. On a cold day you will still be flying with the windows open, and your passenger will freeze.

Carb icing is a problem with the Mercury. VZZ is equipped with a carb temp gauge, and you always want it to indicate a good healthy margin above freezing. A simple knob on the panel moves a diverter-valve in the air intake, and warm air is taken from the engine compartment. This seems to be quite adequate. We were flying on a humid day and I was busy, so I simply left the carb heat nearly full Hot all the time, with no ill effect.

Throughout the summer of 2015, the Lysander will fly at air shows and aviation events throughout Southern and Eastern Ontario and possibly Eastern Québec, sponsored by an investment fund known as the Lysander Fund—a group of highly experienced boutique investment managers, retail distribution arm of Canso Investment Council Ltd, one of Canada’s premier corporate bond managers. The Lysander Fund chose the unique Westland aircraft to represent their offering, stating: “Known for its utilization in covert missions, the Lysander was advanced with a unique wing design embodied in our logo. The unique wing design enabled it to take off and land on very short runways and provided excellent visibility from the cockpit. This made the Lysander very flexible and it was utilized in many reconnaissance missions. The Lysander was involved in many successful covert missions and became an air force stalwart. Lysander Funds’ mission in bringing superior investment returns to investors holds true to its namesake.” Photo: Peter Handley, Vintage Wings of Canada

The “Rich-Cut” is also a Mercury specialty. This is an engine stoppage caused by too-rapid movement to a high power setting. The engine has a very powerful accelerator pump. It floods the intake mixture if the throttle is moved forward aggressively. But I own a Fairchild 24W with a Warner radial engine—and pay for the overhauls myself!—thus tend to move any vintage engine throttle very, very slowly. No rich-cuts were experienced. (The rich cuts don’t seem to be encountered on the ground at low power settings—more likely the opposite, which must be something to do with the idle-jet threshold in the carburetor and the linking of the butterfly valve.) During a go-around, we will move the throttle up gently and smoothly.

Anyway, back to the airfield… no need for an “overhead break” with this airplane—it slows down fast enough! The GUMPFF†† check is very simple: only one fuel tank, no boost pump, the gear is down-and-welded, mixture goes to Normal, pitch to Fine when on final, and open the “Gills” (cowl flaps) for more drag and to set up for any go-around.

Speed target in the pattern is 100 mph. On base and final we let it bleed back to 80 mph. But there are “gotchas” here too. Any large movement in pitch will change the angle of attack (AoA), which will cause the flaps/slats to extend or retract, which will greatly affect your glide angle. If you raise the nose the AoA increases, more flaps deploy, and you drop like a rock with your nose pointing high. Diving towards the button decreases your AoA, causing flaps to retract, resulting in less drag and airspeed increase and you land long. A bit counter-intuitive!

And to make matters worse, the tail is very sensitive to prop-blast, and any power changes will immediately change the elevator’s effectiveness, even without moving the stick, causing pitch changes the pilot may not expect and further destabilizing the approach.

So, the thing to do is get the speed back, establish a glide angle that works, and then try not to change it or the power until touchdown. During the air work, I discovered that it sideslipped very nicely, just like a biplane, and thus decided to employ that. I ended up in a biplane-style continuous gentle slipping turn to touchdown, adjusting the degree of slip as required to maintain the glide path I wanted. I found this to be a very workable technique for the Lysander. No AoA changes, and I touched down where I wanted to each time.

John generally accomplishes a tail-low wheeler on the pavement. I had briefed I’d use the grass, three-point, and I did. I found the Lysander loves a grass surface! Holding it off until the stick was nearly full aft allowed it to settle on with a very mild bump, on all three. I had been a bit concerned about being so high off the ground and possibly flaring at the wrong height, but in practice it seemed quite natural. As the elevator nears the ground it practically touches the grass-tops, so its ground-effect might have something to do with the stick-feel during the flare. Once on the ground, it tracked straight even in the five mph crosswind.

The only unnatural thing was the absurdly low engine RPM. With throttle back against the stop as the speed decreased during roll-out, the prop slowed until I was sure the engine was going to quit. Thus I added power and unnecessarily increased the distance used.

Once taxiing, I looked at the elevator trim scale. Nearly full nose-up! A go-around would have been interesting. As mentioned, it would have required a gentle application of power to avoid a rich-cut, then trim, more power, trim, more power, etc. Fortunately, the airplane is light and it doesn’t take much power to start a climb.

Again the taxi in was interesting, requiring occasionally getting up a head of steam then a solid application of brakes with full rudder to start, or stop, a turn. The Lysander is not an aeroplane to taxi amongst air show obstacles, or near a busy crowd. Better to shut down and get towed in. Once parked, it’s a standard shut-down, being careful to allow the low-speed cut-off knob to snap back into place once the prop stops, to make sure it retracts properly—or the engine may not start next time.

Flying a Lysander is truly a remarkable experience. One gets the feeling that with 20 hours or so in the airplane you could do amazing things with it. Too bad they were never put on floats! Bush-flying with a Lysander would be eye-opening!

But finding tiny fields in blacked-out France, slowing to the back side of the power curve, avoiding the trees and fences and delivering secret agents and weapons... that’s another thing altogether. My hat goes off to the young men who did that. Now that I’ve flown the aeroplane on a good day, at a large airport, in the daylight, my respect for them and what they accomplished is enormous.

Look for Dave Hadfield and the Lysander Fund-sponsored Lizzie at aviation events throughout Ontario in the summer of 2015. Photo: Peter Handley, Vintage Wings of Canada

A nice colour image of a restored Canadian-built Lysander in flight over England in the 1980s. Photo via FleetAirArmArchive.net

* The Trans-Canada Trophy, generally known as the McKee Trophy, is the oldest aviation award in Canada having been established in 1927 by Captain J. Dalzell McKee. In 1926 McKee, of Pittsburgh, Penn. accompanied by Squadron Leader Earl Godfrey of the RCAF, flew from Montréal to Vancouver in a Douglas MO-2B seaplane. McKee was so impressed by the services provided by the RCAF and the Ontario Provincial Air Service that he established an endowment by means of which the greatly coveted McKee Trophy is awarded to the Canadian whose achievements were most outstanding in promoting aviation in Canada.

** Ki-Gass is the trade name of the manufacturer of the excess fuel starting device.

† Vne – Velocity Not to Exceed

†† GUMPFF – Mnemonic for Gas, Undercarriage, Mixture, Pitch, Flaps (cowl), Flaps (wing)