SNIPE — a Centennial Story

In 1967, Canada was celebrating its centennial with exuberant projects and a new Canuck pride from coast to coast. Canada was indeed young, but so was aviation. Just 58 years prior to Centennial Year, the first flight by a powered heavier-than-air aircraft in Canada took place on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Along with massive celebratory events like Expo 67 in Montréal, everyone in the country had pet Centennial projects—from building new community centres and skating rinks to painting Centennial symbols on their houses. In Ottawa, the Royal Canadian Air Force and the National Aeronautical Collection at RCAF Station Rockcliffestaged a celebration of the enormous part played by aviation in Canadian history. A massive air show in Ottawa was planned for early June that would display everything from an ancient Blériot to the absolute latest in RCAF hardware—the Canadair CF-104 Starfighter. One of the pilots who were tasked with demonstrating some very rare First World War aircraft of the Rockcliffe collection was Wing Commander Dave Wightman. Now, in 2017, on the 150th Anniversary of this remarkably wonderful country, Wightman tells us of those days 50 years ago.

This story was written for Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame’s Flyer newsletter. Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame, in Westaskawin, Alberta was created to honour those individuals and organizations that have made outstanding contributions to aviation and aerospace in Canada; and to collect, preserve, exhibit and interpret artifacts and documents, thereby inspiring and educating Canadians. For Canadian aviators, there is no higher honour than to be nominated and selected for membership in its pantheon. For more on the Hall and its members, click here.

Here now is the story of that time half a century ago.

SNIPE

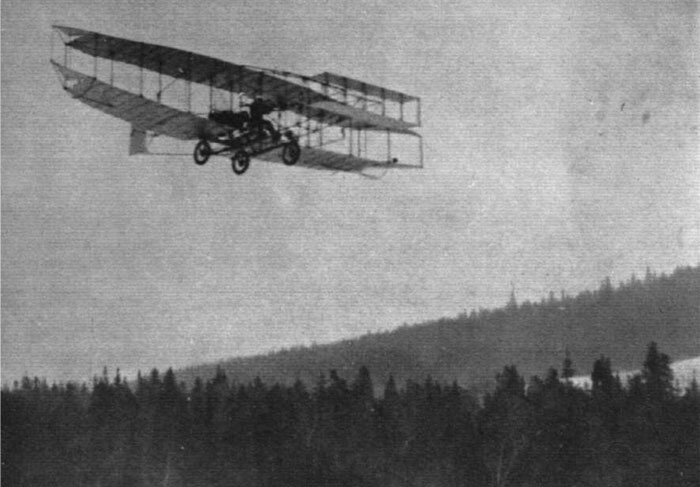

Early in May of 1967, I received a phone call from Wing Commander Paul Hartman who was one of my predecessors as Senior Test Pilot at the Central Experimental and Proving Establishment based at RCAF Station Uplands in Ottawa. Paul had become well-known in aviation circles when he flew a replica of the famous Silver Dart Aircraft, originally flown in 1909 by J.A.D. McCurdy at Baddeck Nova Scotia. The replica had been constructed at RCAF Station Trenton, Ontario in honour of the 50th anniversary of powered flight in Canada. Paul would later be inducted as a member of Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame.

On 23 February 1959, the 50th anniversary of powered flight in Canada, Wing Commander Paul Hartman flew a replica of the Aerial Experiment Association’s Silver Dart aircraft (above), Canada’s first successful powered heavier-than-air aircraft. The original pilot, J.A.D. McCurdy, was on hand that day to witness the re-enactment and shake Hartman’s hand. Top: airmen of the RCAF ready the Silver Dart replica on the frozen surface of Bras d’Or Lake, Cape Breton. Bottom: Hartman flying the Silver Dart. Photo: Flight Magazine, 6 March 1959

Paul was languishing in a staff job at headquarters, but was determined to keep his hand in flying. He volunteered to be the chief pilot for the then National Aeronautical Collection (NAC) museum at Rockcliffe. He told me that he and museum curator Ken Molson had decided to organize an air show to take place at RCAF Station Rockcliffe in June to celebrate Canada’s Centennial. The museum had agreed to release several of their very valuable First World War biplanes to be flown as demonstration aircraft. He told me that the museum staff were very edgy about the whole project because of the priceless value of their exhibits. Paul assured Ken that he would be very careful in the selection and training of the pilots who would fly these artifacts.

Paul said that he was going to fly the Sopwith 2F.1 Camel and asked me if I would like to join him on his team and fly the Sopwith Snipe. He planned to invite several other pilots to join us and fly the other aircraft that the museum had agreed to release. It took me all of 30 seconds to agree enthusiastically.

The NAC had amassed a significant collection of First World War biplanes and other examples of early aircraft that had been flown by Canadian pilots with the Royal Flying Corps. Some of the aircraft were originals and some were replicas carefully constructed to be accurate representations of the originals. The aircraft we would fly were the Camel and the Snipe, as well as a Sopwith Triplane, a Nieuport 17 and an Aeronca C-2. A Fleet Finch two-seater would be used to train our team. The Camel and the Snipe were the two originals, each 50 years old at that time. Each had original rotary engines and they were truly unique museum specimens.

By mid-May, Paul had rounded out the team with several well qualified and enthusiastic pilots. Flight Lieutenant Bill Long would fly the Nieuport 17, Flight Lieutenant Fitz Fitzgerald the Sopwith Triplane, Flight Lieutenant Neil Burns the Aeronca C-2 and Flight Lieutenant Jock MacKay the Fleet Finch. The Finch would be used to refresh each pilot in the feel of flying a tail-dragger aircraft.

Related Stories

Click on image

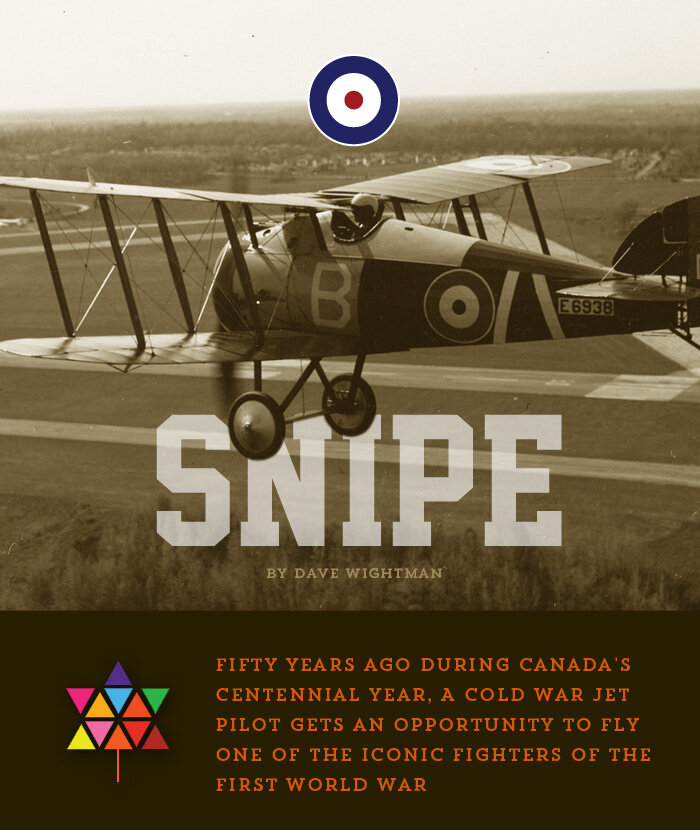

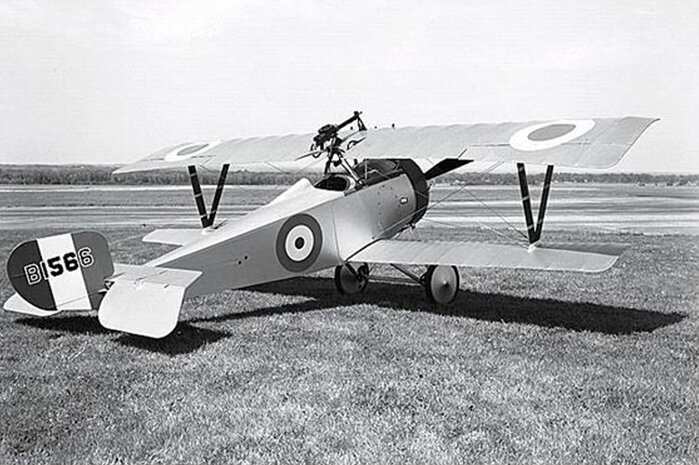

The Sopwith Snipe (E6938) of the National Aeronautical Collection (now the Canada Aviation and Space Museum (CASM)) on the grass at Rockcliffe in 1967. Not more than 100 Snipes reached France before the end of First World War. After the war the Snipe was adopted as the standard RAF fighter, and production continued into 1919. A total of 497 were built by the end of 1918. While 4,500 had been ordered, 2,056 had been completed by the end of 1919. Many went straight to storage and never saw service. The Snipe is considered to be the ultimate development of the small rotary-engined fighter. While almost as manœuvrable as the Camel, the Snipe was much less tricky to fly. One of the outstanding single-handed air battles of the war occurred when Major W.G. Barker, a Canadian pilot, fought off a formation of fighters. After shooting down a two-seater, he was set upon by 15 Fokker D.VIIs. Although wounded in both legs and one arm, he managed to destroy three of his opponents before crashing. He survived and was awarded the Victoria Cross. The fuselage of his aircraft, complete with bullet holes, is part of the Canadian War Museum collection. Photo and text: CASM

Wightman flies the beautiful Sopwith Snipe over parkland near RCAF Station Rockcliffe, wearing his RCAF bone dome helmet after witnessing the injury sustained by fellow pilot Bill Long in the Nieuport 17. In this photograph we see the excellent range of vision afforded the pilot of a Snipe who sat rather high in the airframe and had the benefit of a cutout in the upper wing to further improve visibility. This Snipe was manufactured in 1918 by Nieuport and General Aircraft Limited of England. Details of its RAF history remain unknown, although it probably served abroad, as did most RAF Snipes. Photo: CASM

There are few photos of the Sopwith 2F.1 Camel performing at the 1967 show with Wightman; however it still occupies a place of honour at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum at Rockcliffe. The Sopwith Camel was developed to replace the Sopwith Pup. Camels began to enter the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service in the middle of 1917 and met with immediate success. Although mainly used in western Europe, Camels also served in Italy. Some Camels were assigned to home defence, with the cockpit positioned further back and guns placed on the upper wings. The 2F.1 Camel was produced for the RNAS with more powerful engines and modified armament. A total of 5,490 Camels were built. The name “Camel” was derived from the hump-shaped cover over the machine guns. In order to combat Zeppelins, Camels were flown from barges towed behind destroyers, from platforms on the gun turrets of larger ships as well as from early aircraft carriers. A Camel successfully flew after being dropped from an airship, an experiment testing an airship’s ability to carry its own defensive aircraft. An armoured trench-fighting version was flown, but did not go into production. Photo and text: CASM

The Museum’s Camel (a variant with a shorter wingspan used on ships such as HMS Furious and HMS Pegasus ) was manufactured by Hooper and Company Limited of London, England in late 1918. One of the last Camels to be produced, it was not completed in time to serve during the First World War. It was, however, used by the RAF until 1925, when it was transferred to Canada along with six other Camels. The Camel was used by the RCAF for demonstration flights and as a training airframe. It was loaned to the Canadian War Museum in 1957, and was later stored and displayed at the National Research Council in Ottawa. Restored between 1958 and 1959, and made airworthy between 1966 and 1967, the aircraft was flown between May and June of that year before being transferred to the Museum. Photo: Nieuport Ace at Flickr.com; text: CASM

The Nieuport 17 in flight with either Paul Hartman or Flight Lieutenant Bill Long at the controls in 1967. The Nieuport 17 was one of the classic fighters of First World War. It reached the French front in March 1916, and was adopted by the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service because of its superiority to any British-designed aircraft then in service. Nieuport 17s also served with the Dutch, Belgian, Russian and Italian air forces. Italy built 150 under licence, and Germany was so impressed it asked manufacturers to use some of its features. Six RFC squadrons and eight RNAS squadrons used the Nieuport 17. Even though its lower wing could twist off in high speed dives, the Nieuport became the favourite of the leading allied air aces. The Canadian ace, W.A. “Billy” Bishop, was awarded the Victoria Cross while flying a Nieuport 17. Photo and text: CASM

The Nieuport 17 of the National Aeronautical Collection at RCAF Station Rockcliffe in 1967 warming up with Bill Long in the cockpit and Danny Jones about to pull out the chocks. In the background the driver of a flagged RCAF staff car waits. Perhaps a general officer was there to witness and approve the display. For anyone familiar with Rockcliffe, this area is easily recognizable as the east end of the airfield with the road to the Rockcliffe Flying Club. This Nieuport 17 was built by American amateur airplane-maker Carl R. Swanson in 1961 as a flying replica. A generous donor purchased the aircraft for the Museum in 1963. It was refinished to match the airplane in which the famous Canadian ace William Avery “Billy” Bishop earned the Victoria Cross. Wing Commander Paul A. Hartman took the aircraft on its first flight in May 1967, at Rockcliffe airport. Photo: Bill Ewing

The Sopwith Triplane photographed in the pre-Second World War hangar facility that housed the National Aeronautical Collection at the time of the flights as told in this story. The Triplane was a successful attempt to produce a fighter with outstanding manœuvrability and excellent visibility for the pilot. Records of procurement are very confused, but the Royal Naval Air Service received all of the small number of Triplanes available. Even though the Triplane remained in front line service for less than a year, it was so successful that it inspired several German triplane designs. Only 150 Sopwith Triplanes were built. The all-Canadian B Flight of No. 10 (Naval) Squadron, equipped with Triplanes, downed 87 enemy aircraft between May and July 1917. Called the Black Flight because of the black markings of their airplanes, their aircraft were named: Black Maria, Black Sheep, Black Prince, Black Roger, and Black Death. Black Maria was the Triplane flown by Air Vice Marshal Raymond Collishaw, CB, DSO & Bar, OBE, DSC, DFC, the great Canadian ace of the First World War. Photo and text: CASM

The Sopwith Triplane known as Black Maria being flown by Flight Lieutenant “Fitz” Fitzgerald prior to the 1967 air show. Unfortunately, following an accident with Snoopy Squadron’s Nieuport 17, the National Aeronautical Collection museum staff were worried about structural integrity of the Triplane and would not allow it to fly. Photo: CASM

The National Aeronautical Collection’s Aeronca C-2 (CF-AOR) in the skies over Rockcliffe in 1967, flown by Flight Lieutenant Neil Burns. The diminutive high wing monoplane was designed to be a cheap and simple flying machine for the amateur pilot. Built at the beginning of the Great Depression, it appealed to those who could not afford larger, more expensive airplanes because of its relatively low price. After the C-2 appeared at a Montréal air meet in 1930, the Aeronautical Corporation of Canada was formed in Toronto. This company imported and sold 17 C-2s and C-3s during the 1930s. Approximately 515 C-2s and C-3s had been made when production stopped in 1937. A C-2 was flown higher than 6,000 m (20,000 ft), and one fitted with special fuel tanks remained aloft for 26 hours. The C-2 was dubbed the “flying bathtub” due to its unusual fuselage contour. Photo and text: CASM

Members of Snoopy Squadron’s ground crew prepare to start the collection’s Aeronca C-2 at Rockcliffe, as a photographer prepares to capture the scene. Pilot Neil Burns leans from the cockpit (likely shouting “Contact!”) as a mechanic prepares to swing the propeller. Manufactured in 1931, the collection’s aircraft was the eighth C-2 built by Aeronca. It was originally sold to G.A. Dickson of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and then passed through the hands of several owners. A more powerful engine was installed prior to the National Aeronautical Collection acquiring it in 1967. The NAC replaced the original vertical tail with that of a late-production C-3. Photo and text: CASM

The “squadron” was completed with the addition of a skilled and dedicated maintenance group consisting of both RCAF and museum aircraft technicians. They were Squadron Leader J. Murphy, Mr. A.D. Fell, Sgt. W.D. Scholey, Mr. C.E. Adams, Cpl. C.S. Gallison, Mr. W. Merrikin, Cpl. L.S. Moody and Mr. C.G. Aylen. Of course, we informally dubbed ourselves “The Snoopy Squadron.”

We began our training with a flight in the Fleet Finch with Jock McKay. A couple of quick circuits and we were all good to go. I logged my training flight on 16 May 1967 with a duration of 15 minutes. Two days later, after a briefing from Paul, I took off in the Snipe for the first time. The flight lasted 25 minutes during which I learned a great deal about flying First World War biplanes. It was an exciting flight almost equaling the thrill of my first solo flight during initial training in the Harvard aircraft back in 1951.

Over the next three weeks, until the Centennial Air Show on 10 June, the team flew as many practice missions as the weather and other commitments would allow. We had the field to ourselves as there were no other aircraft using Rockcliffe airfield during that period. Our line shack was the airport grass in the summer sunlight. We would assemble there and watch as the crew hauled out those magnificent old airplanes and prepared them for flight. It was just like the operations of a First World War squadron at Cambrai or Arras must have been in 1917.

Those three weeks of work-up did not go without incident. The Nieuport 17 came to grief one day as Bill Long was transiting over the field in straight and level flight, getting the feel of things. Those of us watching on the ground saw the aircraft suddenly shedding bits of aluminum from the engine cowling. As we watched, the cowling detached, moved forward and was chewed up by the propeller. The engine ground to a halt and Bill began a left gliding turn to get back onto the grass of the airport. As bad luck would have it, the tried-and-true emergency landing straight ahead was not an option for Bill as the RCMP musical ride was out in force on the field into which he would have pancaked. He very nearly made it to the grass at Rockliffe but as he crossed the fence he struck the ground hard, throwing the aircraft up onto its nose. We watched in horror as the aircraft teetered there on its nose and then slowly settled in a precarious vertical position. Sprinting to the aircraft, a half dozen of us broke all records for the 200 m dash. Bill was still in the cockpit looking very groggy and bleeding from a gash caused when he struck his forehead on the machine gun. We helped him exit and after a little medical attention Bill was fine. The same could not be said for the Nieuport 17. The Nieuport was not able to fly in the show and the National Aeronautical Collection museum pulled the Sopwith Triplane over concerns for its structural integrity.

On one of my flights I was flying the Snipe east to west over the field when I saw an aircraft approaching rapidly from the west at low altitude. We had no indication there would be other traffic that day and of course we had no radios on board so I simply kept out of his way. To my amazement, it was a Hawker Hurricane fighter aircraft of Second World War vintage. We found out later that Bob Diemert from Carman, Manitoba had arrived at Uplands in his restored Hurricane and decided to have a look at Rockcliffe. No harm done, but afterwards I couldn’t help chuckling at the thought of someone telephoning the Directorate of Flight Safety and telling them that there had been a mid-air collision between a Sopwith Snipe and a Hawker Hurricane! There would not have been much left of the Snipe.

Bob Deimert’s Hawker Hurricane Mk XII at Rockcliffe that same summer. The nose art depicts a black leather flying boot kicking Adolph Hitler in the arse, the much celebrated nose art of Hurricanes belonging to 242 “Canadian” Squadron in the Battles of France and Britain. Photo: Bill Ewing

On another of my flights, I made what I thought was a beautiful landing on the grass at Rockcliffe only to discover that I had landed on the cricket pitch! No harm done to the cricket pitch, but I was ribbed about it frequently.

The Museum Snipe, E6938, was built in England in 1919 and imported to the United States around 1926 by Reginald Denney. It became a movie star, appearing in the Hollywood film “Hell’s Angels”. After the film was completed, E6938 became a museum exhibit in Los Angeles and spent the next 20 years or so in various United States locations, finally becoming the property of the USAF. In 1953 an aircraft restoration expert, Jack Canary, acquired E6938 and began an epic restoration project. With the help of interested individuals and organizations on both sides of the Atlantic, Canary produced a magnificent example of his craftsmanship. In 1960, it was widely acclaimed as the finest restoration of a First World War aircraft anywhere. When it appeared on the market for sale in 1964, Snipe E6938 was purchased by the Canadian War Museum.

Dave Wightman flies the Sopwith Snipe eastward in 1967 along the shore of the Ottawa River north of RCAF Station Rockcliffe’s three runways. The single remaining runway still in operation today is the one that runs right to left just beneath the Snipe’s fuselage. The present day Canada Aviation and Space Museum, sits in the central triangular grass area in the middle. Photo via Dave Wightman

A member of the Snoopy Squadron ground crew holds down the Snipe’s tail while Wightman runs up the Bentley rotary engine.

The airplane is powered by a Bentley rotary engine developing close to 200 horsepower. A rotary engine has its crankshaft fixed to the aircraft and the entire engine rotates about the crankshaft. The propeller is bolted to the engine in order to provide thrust for the forward motion of the craft. The result is that the pilot must cope with the effects of a gigantic gyroscope attached to the front of his airplane. The way a gyroscope works is that if you apply a force to it, the gyroscope will move in a direction 90° away from where the force was applied. Everyone who has ever held a small gyroscope in their hand will be familiar with this effect. In the Snipe, the result for the pilot was that, in a right turn, the nose would drop and in a left turn the nose would rise. So the pilot had to use left rudder no matter which way he was turning, just more of it in a left turn. I am sure there was some reason for this bizarre design but it has been lost in the mists of time. Suffice to say, the stability characteristics of the aircraft would be totally unacceptable in a modern fighter!

Wing Commander Dave Wightman ponders the complexities and eccentricities of the Bentley rotary engine. Photo via Dave Wightman

Another interesting feature of First World War airplanes was the lubrication system attached to the engine. Castor oil was the lubricant used and it was a simple flow through system. A tank full of castor oil fed the lubricant through the engine and vented it overboard. There was no recirculation of the oil. Now we can understand the need for the white scarf that pilots wore. Their goggles quickly became coated with castor oil and required frequent wiping. Not only that, but the pilots ingested significant quantities of castor oil flying several missions per day which presumably meant that they did not suffer from constipation! Mercifully our flights were so few and so short that we did not experience this difficulty. Following Bill Long’s head injury I decided to wear my standard jet hard hat during the practice flights but wore a leather helmet and vintage goggles for the show day. And of course, the obligatory white scarf!

The Bentley rotary engine started very reliably with a couple of hand pulls from the ground crew. There were three levers which the pilot used to adjust the engine RPM. There was a throttle control, a mixture control and a spark advance control. I don’t think any of us ever figured out exactly how to set these levers properly, but after fiddling around with them until the engine was running more or less smoothly, we simply left them alone. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it! The airplane was designed with something called a blip switch. This was a pushbutton mounted on the control stick and operated by the pilot’s thumb which cut the ignition completely allowing the engine to freewheel. Using the blip switch to control all descents, especially for final approach and landing, meant that the engine was either at full throttle or cut off completely according to the flight profile.

The primitive cockpit of the Sopwith Snipe with the complicated engine control levers at lower left and the “blip” switch in the centre of the circular spade grip. Photo: CASM

On 1 June 1967, having become more or less comfortable flying the Camel and the Snipe, Paul Hartman and I launched twice on a perfect morning so that photographs could be taken of the two historic aircraft in flight. The picture of the Camel and the Snipe in formation over the Ottawa River was a unique and evocative photo. It eventually graced the cover of Ken Molson’s book, Canada’s National Aviation Museum: It’s History and Collections, published in 1988.

Wing Commander Dave Wightman in the Sopwith Snipe (left) leads Wings Commander Paul Hartman in the Sopwith Camel over early spring landscape along the Ottawa River with Kettle Island and the Province of Québec behind them. Photo: Canadian Aviation and Space Museum

At last, on 10 June 1967, the team arrived at Rockliffe for the Centennial Air Show. A large crowd had assembled and there was a celebratory feeling in the air. A well-known vintage aircraft collector, Cole Palen of Old Rhinebeck NY, had agreed to put in an appearance with his Blériot Monoplane and Bob Diemert would fly his Hurricane, this time fully coordinated with the rest of us.

As far as the Museum aircraft were concerned, we conducted the flying display with great care due to the value of these priceless exhibits. We limited ourselves to a series of level flypasts close to the crowd with the pilot waving to the onlookers and waggling his wings rather gently. At each end of the pass a climbing “chandelle” turn would be performed to reverse course for another pass. The level part of each pass was performed at an altitude of 100 feet or less and at a speed of around 75 knots (the equivalent of about 140 km per hour). The audience had an excellent close-up look at the old aircraft and a good whiff of castor oil to boot!

The Sopwith Triplane running up its engine at Rockcliffe with members of Snoopy Squadron’s ground crew holding her steady. In the background can be seen a privately-owned Blériot monoplane (once owned by the legendary Cole Palen of Old Rheinbeck), which took part in the aerial display. Photo: Bill Ewing

After we all had landed and shut down our engines, we climbed out and bade farewell to what, for me, was the most memorable flying experience of my entire career. That was true in spite of the fact that I was flying a variety of different aircraft types during the same period in my job as Senior Test Pilot at the Central Experimental and Proving Establishment.

A single page in my logbook shows that I was flying the Sopwith Snipe, the Canadair CP-107 Argus maritime patrol aircraft, the Canadair CT-133 Silver Star jet trainer and the Lockheed CF-104 Starfighter supersonic jet fighter concurrently. I doubt there is another logbook page to match it anywhere!

By Dave Wightman, MGen (Ret’d), Royal Canadian Air Force

Dave Wightman poses for his obligatory hero shot in front of a CF-104 Starfighter on the snowy ramp at 4 Wing, Baden Soellingen, Germany two years later in the winter of 1969–70. At the time, he was Commanding Officer of 422 Strike/Attack Squadron. The squadrons of the wing were taken from the nuclear bomb delivery role the following year and 422 was disbanded, but Wightman remained as CO of 441 Tactical Fighter Squadron, one of only three squadrons that remained in Germany. Wightman racked up 890 hours in the Starfighter out of his 6,717 total flying hours on about 35 different types of aircraft. Photo: Dave Wightman

Additional images related to the 1967 Centennial Air Show at Rockcliffe

Members of Snoopy Squadron tow the Sopwith Camel out to the grass alongside the active runway at Rockcliffe. The machine’s tail skid would have been damaged dragging it over the concrete ramp, so the tail was lifted and strapped onto a wheeled cart which was towed by a base Jeep. Photo: Bill Ewing

Sopwith F7.1 Snipe E6938 looking worse for wear at the Ontario, California airfield—likely before it was purchased from Reginald Denny by Jack Canary. There is a hand-painted sign in the cockpit but it’s impossible to determine what it says. Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum

The Snipe with tail number E6938 flown by Wightman in the 1967 air show at Rockcliffe was previously owned by Jack Canary who restored it between 1953 and 1960. Since it was sold to the National Aeronautical Collection in 1964, after restoration, this is likely taken at the time it was first purchased by Canary. The lineup of aircraft—the all white P-80 Shooting Star, B-29 Superfortress and Super Constellation in the far distance—are right for that time period of the late 1940s/early 1950s. Photo via San Diego Air and Space Museum

Following its immaculate restoration in 1964, Jack Canary (middle back) proudly shows off the Snipe to Reginald Denny (left) and his son Reginald Denny Jr. (right) and TV broadcaster Clete Roberts (in dark jacket). In 2002, Denny Jr. wrote: “Actually my father brought three Sopwith Snipes into this country. Two were used in movies and crashed. The third was left on display at the Los Angeles Museum and was kept in near perfect condition. During 1952 the L.A. Museum advised dad they no longer had room for the plane and he should make arrangements to have it removed. My father ignored this notice and the plane was sent to the Ontario Airport east of Los Angeles where it was left to rot in the weather. Sometime during the sixties a WW-1 aircraft buff by the name of Jack Canary discovered the rotting plane and using funds from the Airforce Association restored it to better than new, flyable condition…he even went to England and received information and permission to use the original insignia from the squadron to which the Snipe was attached. When Canary attempted to find a home for the plane and receive reimbursement of the money he personally invested, he found he was unable to do so because my father still held title. My father signed over the title and The Museum of Aviation in Canada paid Canary $25,000.00 for the plane which covered Mr. Canary’s personal cash outlay. At the time, this was the only flyable Sopwith Snipe remaining in the world. I believe another has since been put together somewhere.” Photo: ctie.monash.edu.au

Along with the incident with the Nieuport 17, one of the Golden Centennaires’ Avro 504s (G-CYCK) also had a landing incident at Rockcliffe. The pilot Gord Brown (left) was executing a rolling landing two-pointer when the weighted skid struck a hummock and the aircraft pitched up onto its nose. Luckily the Golden Centennaires team had a second Avro 504 (G-CYEI) to fill in for this one. Photo: Bill Ewing

Bob Deimert in his Hurricane XII warms up prior to his display at the Centennial air show at Rockcliffe, with the second Avro 504 (G-CYEI) belonging to the Golden Centennaires team in the foreground. Photo: Bill Ewing

Two very fine formal shots of the National Aeronautical Collection’s pristine Nieuport 17 at Rockcliff. The Nieuwport was damaged in the accident prior to the air show. One of the accident investigators, Bruce Burgess, recalling the investigation recently said “The lower left of the four engine mounts on the Nieuport 17 had failed according to my metallurgist at the MAT Labs. When the aircraft was purchased by the museum, a certificate was received vouching that engine mounts had passed x ray testing. It’s my opinion that if Bill hadn’t cut the ignition as quickly as he did, the powerful torque of the rotary would have ripped the engine off of the aircraft.” Photo: CASM