FOR THE RECORD — No.1 Bombing and Gunnery School, Picton, Ontario

The stories of the heroic airmen of the Second World War that we are all familiar with and which command our interest and our passion for history, are stories of flight training and the adventures and tragedies of combat pilots and aircrew. Stories of the courage and professionalism of Bomber Command Pathfinder crews. Stories of B-17s struggling for home with heavy damage and dead or wounded aboard. Stories of handsome and insouciant Oxford graduates battling the Luftwaffe in the skies over London. Stories of lone wolf aces that no one quite seems to understand. Stories of carrier pilots who risked their lives with every launch and recovery. Stories of wild abandon on leave, deprivation and longing, lost airmen and no known graves, fiery death, fate, weeping widows, stricken mothers, and broken fathers.

The faces of military aviation in all theatres of the Second World War were these stories and these men, but they are not the whole story of the war effort. Not even close. The truth is that the pilots in a fighter squadron represented a small fraction of its strength, the greater proportion being adjutants, intelligence officers, flight surgeons, mechanics and fitters, batmen and clerks. While a major fighter air base like RAF Biggin Hill or the RCAF bomber base at RAF Linton-on-Ouse, from which combat operations were mounted, became storied for the exploits and terrors of their pilots and aircrews, they were populated by hundreds, even thousands of RAF airmen and airwomen and civilians who underpinned the very existence of operations and whose stories are of equal value, but rarely studied.

In theatres of war far from their home countries, Canadian, British, Australian, New Zealander and American men with a broad spectrum of recently-acquired skills like airframe repair, engine maintenance, electronics, firefighting, cooking, construction and motor pool operation shared many of the same considerable dangers and deprivations as their aircrew comrades—death by U-boat, death or injury by enemy aerial or ground attack, death by disease, poor nutrition, extreme weather and abject loneliness. Save for the rare personal memoir or websites that capture spoken and written memories such as The Memory Project or the BBC’s WW2 The Peoples War, the stories of the hundreds of thousands of air force support staff are simply drifting unheard and unrecorded into the vapours of time.

Without these men and women, the fighter and bomber crews could not be trained, nor could they take the fight to the Nazis or the Imperial Japanese. Without the stories of all airmen and airwomen, the true picture of the air war is not fully understood.

At the beginning of the Second World War, Canada signed an agreement with fellow members of the British Commonwealth that begat the vast, nation-wide civil works and military training program that we know as the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. In just a couple of years, Canadians scouted out, surveyed, designed and built airfields and facilities for 32 Elementary Flying Training Schools, 29 Service Flying Training Schools, 10 Air Observer Schools, 11 Bombing and Gunnery Schools, 6 Air Navigation Schools, 4 Wireless schools, a Flight Engineer School, 2 General Reconnaissance Schools, 7 Operational Training Units, 3 Flying Instructor Schools, 66 Relief Airfields and a variety of facilities for induction, basic training, and the training of armourers, radio technicians, cypher clerks and the various other skills that keep an air force operational.

In these bases, young Canadian men learned the skills that would take them to the war and sadly, in many cases, to their deaths. Alongside the Canadian boys were Australians, New Zealanders and plenty of Americans who were ahead of their government in taking on the Nazis. While all the bases were designed and completed by Canadian architects, engineers and private construction companies, not all of them were operated by Canadians. At the beginning, a number were manned largely by staff or instructor pilots, mechanics and support airmen from the Royal Air Force. One of these RAF schools was No. 31 Bombing and Gunnery School at Picton, Ontario in Prince Edward County on the shores of Lake Ontario. Picton lies in the heart of “Loyalist country”, the region immediately north of the St. Lawrence River and the American border where British subjects loyal to King George III fled and resettled during the American War of Independence.

Following a signed agreement with the Royal Air Force to train aircrews for combat in Canada, architects and draughtsmen got down to the business of designing standardized hangars, messes, barracks, repair facilities, gun butts, guard houses, classrooms, administration facilities and all the infrastructure a station might need. Every base across Canada had a unique footprint made up of these standardized structures set next to a runway layout that was almost always triangular. This gave all the bases a similar visual quality. Thanks to Pierre Burton, many Canadians look upon the construction of the national railway as the largest engineering and public works project ever built in Canada. It was eclipsed however by the BCATP’s extraordinary size and rapidity. Within a couple of years, scores of large airfields were built. Instructors and support staff were recruited; aircraft, vehicles and equipment were purchased and delivered; syllabi were developed; and doors were opened. Of all of these bases, many were dismantled, many remain as municipal airports and only a handful still retain some of the original BCATP buildings (usually hangars). Only one—the BCATP station at Picton, the former home of the Royal Air Force’s No. 31 Bombing and Gunnery School—still has all or most of its wartime structures still intact. Camp Picton is today the Picton Airport and a time capsule worth the trip.

The young RAF airmen who would learn the gunnery and bombing trades at Picton were preceded by other young men whose job it would be to get the school and its many parts operating smoothly and then stay on to keep it working as a well-oiled machine. These men were recruited by the RAF after the start of the war in 1939 and as a result of the Battle of Britain. Trained in the art of being an airman and in their various technical skills in Great Britain, the young men boarded troopships in Liverpool and crossed the North Atlantic in solo high-speed liners or in convoy at a time when Admiral Dönitz’ U-boats were ascendant. Once in Halifax, these men were processed and given orders and a train ticket to Picton, Ontario, there to begin a lengthy period away from their families and hometowns.

Recently, a personal photo album from one of those young airmen, Aircraftman Second Class (AC2) Arthur Norris has come to light following his death this past December. Arthur’s story was about to vanish with him as he was not a man to celebrate his contribution to the war nor to put himself at the centre of it. He was a man, however, who valued the friendships and memories that he had made and he kept a photo album of his time in Canada which has been shared with us at Vintage Wings by his great nephew Steve Merrill, an engineer with SNC-Lavalin in Thailand. Steve wrote: “I recently acquired a number of photos that were taken by my Great Uncle when he was assigned to Picton as a driver with the RAF in 1941–42. The photos include shots of aircraft mainly Fairey Battles, Base vehicles like fuel bowsers and views of the base from ground level and from the air. I don’t really know what to do with the photos but I feel that they may be of interest to researchers so I decided, after a Google search led me to your website, to ask your advice. I am quite happy to scan and send copies to you if you are interested as long as you publish them so that they are accessible to all researchers.” Without seeing any of the photos, I immediately agreed to publish Norris’ album in its entirety. We have neglected the role played by Norris and other junior ranks and non-commissioned officers who made the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan the huge success that it is.

With the administrative building in the background, this is a shot of “Oak Gate”, the main gate at No. 31 B&GS, Picton. Note that the speed limit throughout the station was 10 mph, likely a difficult limit to stay within for testosterone-fuelled transport drivers like Arthur Norris. Designed only to last a few years, most of the BCATP fields have disappeared or long lost their structures, save for hangars at some bases. Picton is the only relatively intact base left in Canada, with these lightly constructed wood structures now over 75 years old. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Related Stories

Click on image

The photos in this story come from an album belonging to Aircraftman Second Class Arthur Norris of the Royal Air Force, seen here (at right) with a friend warming in the sun on the steps of their H-Hut barracks at Picton’s No. 31 Bombing and Gunnery School. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

A contemporary photo of the same H-Huts at Picton, Ontario’s No. 31 Bombing and Gunnery School. It seems that the cedar shake siding was likely natural and unpainted. The metal roofs in this photograph were added recently. Photo: Bruce Forsyth, MilitaryBruce.com

Serving in the Royal Air Force in Canada meant extreme variations in the type of clothing required. These two shots, taken outside his H-Hut demonstrate the extremes. The winter coat at left seems to be tied firmly with wick cord, perhaps an adaptation required for a poor design. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

I wrote to Mike Norris, Arthur’s son for some background information about his life and upbringing. I received a letter from Mike that described Arthur’s early years and the little he knew and understood of his father’s military career and his experiences in Canada. Arthur’s reluctance to make a big deal of his steadfast service to his country meant that Mike Norris had few details of his father’s service, but through the photos from his album, we are able to piece together for the record, in images and words, the humble yet rich story of one airman’s service in the Royal Air Force of the Second World War. Rather than rewrite the details of Norris’ life, let Mike Norris tell us about his dad.

Here, for the record, is the service of Arthur Norris in his photos and the heartfelt words of his son:

“Arthur Norris was born on November 12th 1920, the youngest of three children, in Rochdale, which was then classed as being in Lancashire, but is now in Greater Manchester. At the time, Rochdale was a cotton-spinning and weaving town with all the associated noise and smells of the cotton and cloth, bleaching and dyeing industries. In the early 1920s, his parents, James Leonard and Lillian, together with Arthur and his older siblings Leonard and Ivy moved to Haslingden, Lancashire, another cotton weaving town some 10 miles away.

Arthur attended St James School, known locally as the “Church School”, and later Haslingden Grammar School. It was at the former that he met my to-be mother, Margaret Hannah Mead.

After leaving school early, (I believe that finance may have been a factor in those days), he worked at a cotton mill as a clerk and would also have worked with his parents, who were then running a fruit and vegetable shop. It would be here that his father taught him to drive the small flat-bed truck that was used both in connection with the shop and as part of a separate business of light removals. In Haslingden as in many small local towns, poverty was never too far away and so a small truck would easily be able to remove the contents of an entire household in a single trip.

I do not know the circumstances of his joining the RAF, but clearly his ability to drive a commercial vehicle stood him in good stead and facilitated his posting to Picton. Sadly, my knowledge of his time there is virtually zero. However, as I mentioned, there did seem to be an arrangement whereby UK members of the base were “paired” with local families. Memory from the 1950s tells me that in his case, it was a certain Mr. & Mrs. Terry. She was Mae (May?), but her husband I do not know. I believe that their address was 507 Woburn Avenue, Toronto 12. Certainly she was still in touch with him in the 1950s and possibly early 60s and always signed herself as his Canadian Ma.

All I can add about his time in Canada is that it was there that he was introduced to sweet corn, which would have been virtually unknown in the UK at the time, or else considered to be a great luxury, and it was a love that he carried through the rest of his life.

From Canada, he would have returned to the UK before being sent onwards to India. I know nothing of his time there except that he hated curries (another lifelong passion) and that he taught locals to drive.

At the end of the war, following his demobilisation, he returned to his job at the mill in Haslingden and to courting my mother, whom he married in July 1948 in Haslingden. I was born in March 1950 and am their only child.

He left the mill sometime in 1951 to work (self-employed) driving a truck locally. Following the retirement of his parents and probably with some financial assistance, Arthur and Margaret bought a grocer’s shop in Burnley, Lancashire in late 1952. They ran the business together until it became apparent that my mother needed to go to work elsewhere. So she went to work in various local factories and Arthur ran the business pretty much single-handed from 1960 onwards, with help from her at the weekends.

In 1967 they closed the shop, moved a few miles out of town and Arthur went to work for a food wholesaler as a manager and retired from the business in 1985 as a director of the company.

When I married in 1989, Margaret and Arthur “inherited” two grandchildren, my step-daughters, of whom they thought the world and the feeling was mutual. It certainly gave them something else to occupy them in their retirement. Sadly, my mother would not live to see either of them married, as she died of too many cancers on September 17, 2003. Following her death, Arthur lived on his own near to us and not surprisingly became increasingly frail as the years went by, and found himself having to accept more and more help, but only with great reluctance.

After a fall at his home in October 2017, he was transferred to hospital and died on December 23rd 2017 just over a month after his 97th birthday.

Arthur spoke very little about the war to me or in my hearing. As far as I am aware he never kept in touch with any of the other airmen from Canada or later India, so I am unable to help with the identities in the photographs.

As you may gather, my father was the kind of person who kept himself to himself and hence my own knowledge is rather scanty. He was kind, hard-working with a strong sense of ethics and morals that were fairly typical of the time of his birth and upbringing. He liked his independence and was determined to be as little trouble to others as possible. My wife and I called this stubbornness, which apparently I have inherited. His dry sense of humour was particularly appealing to many, including my wife and the girls. In his retirement he gave much of his time to gardening and a small ornamental pond with a few fish that he seemed to have trained – they certainly knew when food was about to appear. He would happily sit and read a newspaper and play some of the puzzles with the girls, or play cards with them, and yet in all his life, I never saw him read a book.

Sadly, as the years passed after my mother died, his deafness became an increasing problem, but seemingly not to him. At Christmas for example, he would watch the girls screaming and laughing as they opened presents and throwing comments at each other, (even in their thirties) and he thoroughly enjoyed being a part of their enjoyment, even if he had no idea what was being said.”

The young man is this photograph appears a number of times in the following Norris photos, but he is never identified. After a heavy snowfall, he and Norris took turns photographing each other in the brilliant white stuff, likely to send home to Great Britain as evidence of their hardships in the Great White North. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

An aerial view of the Picton Airport, the former BCATP station for No. 31 Bombing and Gunnery School, with certain buildings highlighted that feature in the Arthur Norris Collection of photographs. Photo: David Edward

The interior of Norris’ H-Hut barrack building reveals a crowded and overly-lit interior where privacy was non-existent. This would be just one of the four wings of an H-Hut and looks to accommodate about 40 junior ranks airmen in two tiers. No doubt, the airmen looked forward to their occasional leaves and trips to places where privacy could be restored. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

All the airmen in each H-Hut shared common toilet and bathroom facilities. No doubt, these facilities would have been very crowded before lights out and first thing in the morning. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Norris (right) and friend patiently await their turn. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Arthur Norris (left) clowns for the camera on the doorstep of an H-Hut barrack building called Airmen’s Quarters No. 10. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

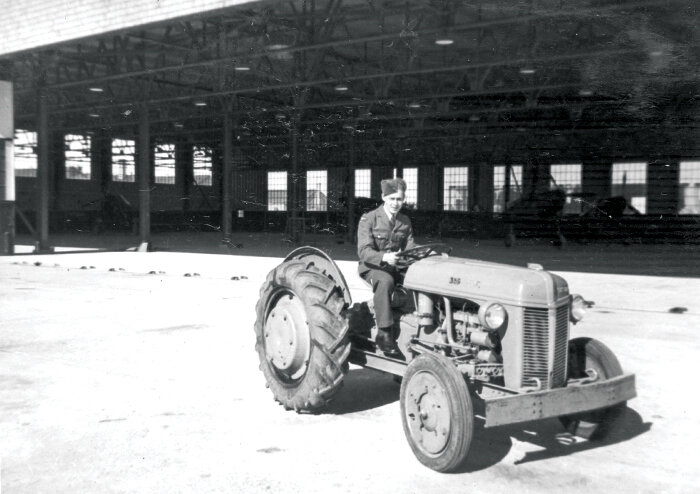

Arthur Norris crossed the Atlantic to work at No. 31 B&GS in Picton, Ontario as an all-purpose transport driver in the motor pool. Most of the images in his collection relate directly to his job as driver. It was evident that he was very proud of his work as witnessed by several photos of himself with various pieces of equipment he was required to master. The smallest of the vehicles that he operated was this 1940 Ford 6N tractor, likely used as an all-purpose tow and utility vehicle, seen here in the summer of 1941 in front of one of the flight line hangars. Note the silhouettes of four Fairey Battles in the dark depths of the hangar. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Arthur Norris poses in October of 1941 with a yellow 1940 Ford 3-Ton fuel bowser (No. 198 P.C.). RCAF Ford 3-Ton trucks usually had dual rear axles, but this fuel truck had only a single axle. The long arms at top rotated outward and held the fuel hoses up and away from the wings when refueling. Drivers like Norris towed, fuelled and recovered aircraft from crash sites. They also drove buses and ambulances. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Arthur Norris poses with a 1940 Ford 1-Ton Ambulance (No. 35 P.C.) outside the motor pool sheds. In addition to driving the various vehicles, Norris and his mates were required to keep them clean and do a little light maintenance. The pride in his work as a driver is clearly evident in this suite of photos. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Arthur (front) and a friend clown for the camera with what appears to be the front end of the Ford 1-ton Ambulance pictured in the previous photograph. Clearly, work was being done on the front end requiring the removal of the grill and fenders. The canvas snap-on cover seen here was a common sight in Canada back in the days of ineffective radiators. The cover would limit the amount of freezing winter air flowing through the radiator vanes and helped keep the engine coolant at a reasonable temperature. Many long distance trucks still use them today. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Down at the motor pool quadrangle on a hot summer’s day, Arthur Norris (right) and other airmen chat with the driver of an RCAF Ford stake truck making a delivery. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Arthur Norris at the helm of an International fire truck (No. 62 P.C.) outside the motor pool sheds at No. 31 B&GS Picton. Following the war, many RCAF vehicles were sold locally for municipal volunteer fire departments. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Taken at another time, Arthur Norris sits proudly in the driver’s seat of the same International fire truck as seen in the previous photograph. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Late afternoon cleanup after the motor pool fire. Perhaps it was fortunate that the fire fighting vehicles were also parked in this building. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

A gauntleted Arthur Norris leans out of the cab of a Lorain mobile crane, grinding its way along the flight line after lifting a wrecked Fairey Battle onto a flatbed truck from Trenton’s No. 6 Repair Depot. The small Lorain Crane was used by both Canadian and American militaries during the war for construction and general heavy lifting. Most bases that had extensive flying operations would have one for crash recovery. These cranes saw heavy use as hardly a week went by without an accident—either flying or taxiing. The date on the back of the photograph tells us this was October of 1941. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

The caption in Arthur Norris’ album indicates that this crash of a Fairey Battle occurred in October of 1941. Could this be the Battle that Arthur Norris lifted with the Lorain tracked crane in the previous photo? During his time at No. 31 B&GS, Arthur Norris would have attended scores of these crashes—some less destructive, others horrific and fatal. Reading through the lists of nearly 800 Battles transferred to the RCAF in R.W.R. Walker’s superb website Canadian Military Aircraft Serial Numbers, I found scores of Battle crashes at Picton, but only three from October of 1941. On 13 October, Battle R7473 suffered Category C3 damage when it crashed at 11:45 in the morning. Three days later on 16 October, Battle L5573 suffered Category A damage from a forced landing at 12:30 PM when its engine failed during a bombing run. Then on 28 October, Fairey Battle K9323, being flown by Wing Commander MacDonald, suffered Category C damage. Category C Damage occurs when the aircraft sustains damage to a major component requiring repair beyond field level resources (C3 damage means that the repair is carried out by a mobile repair party from a depot). Category A Damage means the aircraft is written off. I believe that the incident of 16 October happened away from the base at one of the ranges. Likely, the aircraft in this photo was either R7473 or K9323. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Crashes of station aircraft were part of daily life at any BCATP base during the war. The losses of aircraft, staff pilots, instructors and students were the norm back then because a war was on. But now, this astonishing rate of attrition would be entirely unacceptable. Here, in the winter of 1941–42, a Fairey Battle has come to an untimely end in a farmer’s field near the small hamlet of Cherry Valley, about eight kilometres south southwest of the station. With the propeller blades bent backwards, we know the Battle had power on but was throttled back. If the blades were to strike the ground while the throttle was advanced, the blades would bend forward. It is likely he was attempting to land and perhaps struck an obstacle such as a tree. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

A close-up of the damaged port wing. Perhaps the Battle struck an obstacle or ground-looped heavily and tore the wing and gear off. Most likely Arthur Norris was called to attend the crash with recovery vehicles and equipment. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Norris and his crash recovery team head toward a Fairey Battle that has just made a forced landing in a field of post-harvest stubble. The frequency of such accidents was high and men like Norris were called to operate all sorts of crash recovery equipment—ambulances, cranes, bulldozers and various trucks. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Though the caption accompanying this photo states that this is a crash of an Avro Anson, it is actually a Cessna Crane, a multi-engine trainer used by the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan in far less numbers than the Anson. The wooden propellers do not seem to be damaged, indicating a power-off wheels-up landing. Checking the serial numbers for all the Cranes in the RCAF, I cannot find a record of a Crane with a serial number that ends in 86 or 06 (as this seems to have) having been damaged at Picton. If anyone can find the accident report for this wreck, let me know. Judging by the trees in the background, it happened in the spring of 1942, before the leaves came out. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Arthur Norris poses with a Fairey Battle in front of one of the six flight line hangars at Picton in 1941. Helping to service, tow, fuel and recover these aircraft made Arthur and other motor pool drivers essential to the training of bomb aimer and gunners. As such, they were much appreciated and from time to time, offered rides in the various aircraft assigned to the station. The delicate looking devices hanging down at an angle to the landing gear are hydraulic rams to actuate the gear cycle. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

It is most likely that this young man, a friend of Norris, took the previous photo of Norris, as this is the very same Fairey Battle as evidenced by the number 14 on the gear doors. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Judging by the rounded tank caught in the mirror of this truck, Arthur is driving a fuel bowser out to the flight line where a number of camouflaged ex-RAF Fairey Battle are parked with a couple of yellow Harvard trainers, possibly visiting from No. 31 SFTS Kingston, No. 2 SFTS Uplands or the Central Flying School at Trenton. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Beating up the field. The caption with this photograph states “Canadians Leaving Picton—November 1941” and shows an Avro Anson (possibly) leading two flights of three yellow Harvards at very low altitude across the airfield as they say goodbye after a visit. Though the nearest Harvard SFTS was Kingston, that was a British facility, so it’s likely that these Canadian boys were from Ottawa or Trenton. Judging by their formation skills and the mix of aircraft, my bet would be that these aircraft came from the Central Flying School at Trenton, where some of the best fliers coming out of the BCATP were sent to learn to be instructors, staff pilots or generalists. Despite the constant flying activity at Picton, such a formation beat-up was still a wonderful and inspiring site for the ground crews. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

A Fairey Battle taxies along the flight line at Picton. Note the size of this aircraft relative to the man in the cockpit—the Battle was powered by the same Merlin engine as the Supermarine Spitfire, but was 1,500 pounds heavier and uncomfortably underpowered as a result. It made some sense and had some benefit as a training aircraft, but most definitely not as a combat type. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

An Airspeed Oxford from Trenton trundles along the flight line at Picton in the summer or fall of 1941. That summer/fall there were three accidents involving “Oxboxes” at Picton—all of which were assigned to something called the Composite Training Squadron at nearby Trenton—on 31 July, 20 October and 28 October. The Royal Canadian Air Force ordered 25 Oxford Is in 1938. They were taken from RAF stocks and shipped to Canada in 1939 and assembled by Canadian Vickers at Montreal. Issued to the Central Flying School at Trenton, they were later joined by large numbers of RAF aircraft to equip RAF-managed Service Flying Training Schools, mostly on the Canadian Prairie (Moose Jaw, Medicine Hat, North Battleford, Penhold, Calgary, and Swift Current). Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Two Ansons visiting Picton on a possible cross-country training flight. The two Avro Anson Mk Is in this photo were assigned to No. 8 Service Flying Training School in Moncton in 1941 when this photo was taken. The one closest to the camera, RCAF serial 6274, was built for the RAF as R3451 and taken on strength in December 1940 by Eastern Air Command in Amherst, Nova Scotia where the Canadian Car and Foundry (CC&F) shops assembled it after delivery by ship and rail. It was damaged in a Category 5 incident at Moncton in April 1941. It survived the war after being converted in 1943 to Mk IV standard. The Anson in the background, RCAF Serial 6366, was built for the RAF as well, with RAF Serial number W1976. It was delivered to the RCAF in January 1941 after assembly at CC&F. Both these aircraft did solid journeyman service with almost identical total flight hours—2,009.5 hrs for 6274 and 2,060 hrs for 6366. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

A Fairey Battle is refuelled at the hangar door on the flight line at Picton. It is clear the drivers from the motor pool were also required to fuel aircraft. This Battle has an RAF serial number (K9476) painted on one of its propeller blades, something I have never seen before. I am not sure why this was done—perhaps to identify it on the flight line when parked. I am also not 100% positive that the prop with K9476 on it is attached to Battle K9476. That particular Battle did indeed serve at Picton, so it’s very likely. It was originally taken in strength at No. 6 Repair Depot in nearby Trenton on 8 May 1941, then on to Picton nine days later after assembly. In July of 1941, it was converted to a Battle TT (Target Tug). In March of 1942, it suffered Category C Damage whilst taxiing when it struck another parked Battle (P2304) and tearing off 5 feet of its starboard wing tip. Sent back to 6 RD, it was never fully repaired and was reduced to spares. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Fairey Battle T R7480 climbs away from the runway at No. 31 B&GS while Arthur Norris photographs from the rear seat of what is likely a similar Battle T. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

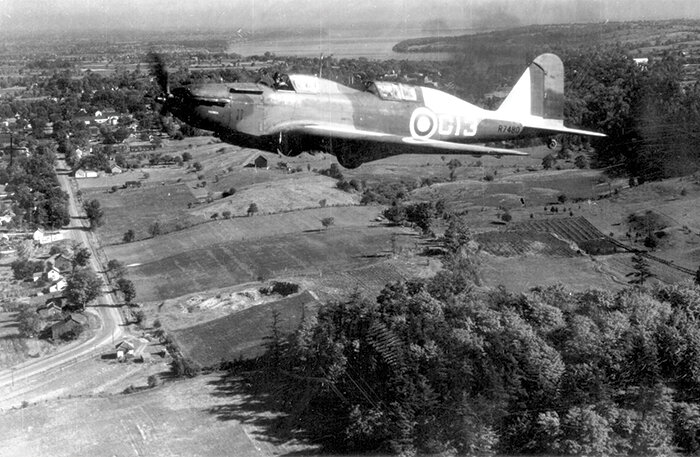

Battle R7480 flies across Prince Edward County farmland in 1942. The strange dual cockpit configuration made the Battle T look like it had been rear-ended by another Battle. The bright white patches on wings, fuselage and tail are actually bright yellow, designed to make the aircraft more visible and painted over the original factory camouflage. Had the type been designed and built as a training aircraft in Canada, they would have been painted overall yellow in the factory. R7480 was built along with 99 others as a dual-cockpit trainer and delivered to Canada and taken on strength at No. 6 Repair Depot, Trenton, Ontario on 1 July (Canada Day) 1941. It was taken out of service at No. 31 B&GS on 24 February 1943, sent to No. 6 RD where it was eventually scrapped in March 1944. Of the 2,185 Battles built, 802 were shipped to Canada as target tugs, gunnery platforms or, like R7480, dual pilot training. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

A nice shot of Battle T1 R7480 climbing out over Prince Edward County in the late afternoon. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

From down in the gully alongside the Iejima airstrip, another photographer takes a colour shot A poor photo, but a great visualization of the proximity of Picton’s airfield (right) to the town (upper middle). The big white area next to the runways is actually the roofs of the six hangars at Picton. The easily descernable white looping road is today’s County Road 22. Put that into Google Street view and follow 22 until you come to the airport and the main gate—a bit like driving back in time. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Likely from the same flight, the Fairey Battle climbs over downtown Picton with Main Street fairly evident. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

In the hard and snowy winters of the Lake Ontario North Shore, snow ploughing and removal would be an important part of what Arthur and his mates did, especially in the days after a major “dump”. People who live in Ontario are familiar with the bright snow-blind sunshine that reveals the wonderland the morning after a major blizzard and which is evident in this photograph. No doubt this would be amazing to Brits like Arthur Norris. This shot looks southwest down Ubique Avenue from the intersection at Royal Road. To the left we see the H-Hut barracks where Arthur lived and the low building at right is where some of the vehicles he drove were parked. Up the road comes a snow-clearing bulldozer. A classic scene from a Second World War training base in Canada. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

After a heavy snowfall, Arthur takes a photo looking past the H-Huts where he lived to the hangar line in the far distance. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

A ploughed road at Picton. It appears this was taken in the afternoon judging by the long shadow, with Norris looking northeast up Ubique Avenue, likely standing right outside his H-Hut 10. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Judging by the state of the shed in the background, this looks to be the same garage gutted by the fire shown earlier. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Snow clearing at the motor pool, airmen shovel snow into the bed of an RCAF dump truck wearing chains. The men are forced to do it all by hand with heavy steel coal shovels—hugely inefficient by today’s standards. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Out on the airfield itself, considerably more efficient equipment was employed—like this purpose-built Walter snow blower photographed in action by Arthur Norris in the winter of 1941–42. Here in Ontario, massive snow blowers are a common thing yet still attract the slack-jawed attention of people as they chew their way down the street on a winter night. The Walter Motor Truck Company was an American truck manufacturer specializing in heavy duty all-wheel drive trucks. The company also built snow removal equipment and fire apparatus being particularly well known for its aircraft crash trucks. Top photo: Arthur Norris Collection; Bottom:

In this official RCAF photo of a similar Walter truck we can see better detail of the snow blower attachment seen in Norris’ photograph. Photo: Library and Archives Canada

A hard Canadian winter was clearly a new experience for Norris, one that soon wears on them. Like all us Canadians at the first sign of a warm late spring sun, Norris and his chums throw down some blankets and take off their shirts on the lawn outside their H-Hut and warm their weary bones. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Another shot of the lads enjoying the sun at Picton. I believe the man at left is Norris. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

I do not know who this fellow was, but he is in many of Norris’ photos, leading me to believe this man was perhaps his closest mate. Here he relaxes at Picton amidst the dandelions. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Being a Royal Air Force training base, soccer replaced the traditional Canadian sports of hockey in winter and baseball in summer. Arthur Norris (in white uniform) poses with members of the No. 31 B&GS Headquarters soccer team. Many of the boys on the team can be seen in other Norris photos in this series. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Eleven Royal Air Force airmen, perhaps equipment operators from the motor pool, pose for a group photo outside one of the H-Huts on the barracks line in July of 1942. Arthur Norris is standing third from right. The rock-walled flower boxes look like they were added as a personal touch perhaps even executed by these men, as they seem pretty proud of them. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Off on Adventures

A Canadian National Railway (CNR) K-3-B locomotive idles at the Picton train station, likely bringing in more student gunners and bomb aimers from the United Kingdom. In today’s world of cheap and total coverage airline travel, it’s easy to forget the importance of the train to the deployment of the 155,000 airmen who were trained under Canada’s British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Each man took the train to Manning Depot, then another to Initial Training School, then others to Elementary and Service Flying Training or schools for bomb-aiming, flight engineering, gunnery, radio or navigation and then on to Halifax to ship out. During all these steps, recruits would also use the train for leave, either to visit family or bigger cities for entertainment. This particular locomotive (5595) was built in 1911 for the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) at their shops in Stratford, Ontario and then bought by the CNR when the GTR collapsed in 1923. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

I found a clearer photo of CNR locomotive 5595 idling at nearby Belleville, Ontario ten years earlier. I include it here to show that these short haul locos likely operated on the same lines most of their operational lives—5595 running up and down the north shore of Lake Ontario and parts of Southern Ontario until it was scrapped in June of 1957. Photo: City of Vancouver Archives

On their time off, Norris and friends could take in a film in Picton or venture farther afield. Lucky for them, Picton was close to some of the most beautiful country in all of Canada—the Thousand Islands—an archipelago of ancient and spectacular islands midstream in the St Lawrence River. On one of their adventures in the region, the lads seem to have suffered a breakdown. With the simple engines of the day and a car full of motor pool drivers, it was likely a quick fix before they were on their way. To me a late 1920s Chevy or Ford look too similar to make a call here, but I’m guessing this is an old Ford Model A. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

At first, I wasn’t sure what this vehicle is that Arthur Norris is driving. The vertical post behind the seat is puzzling and it does not look like any of the vehicles in the photos that follow. Of note is the wood lathe headliner, the horizontal wood aft the post, driver’s side vent window and the sharp corner of the driver window—possibly a 1941 Ford Super Deluxe “Woody” Station Wagon. According to Hanno Spoelstra of Maple Leaf Up Forum, The Canadian Ministry of Defence placed orders for Station Wagons in various variants at Ford. The Station Wagons came in several variants, many with right-hand drive for overseas use. The Station Wagon that Arthur Norris is driving is clearly a left-hand drive vehicle. So this is one of the vehicles ordered for domestic use, and since these were not to be used overseas, the level of militarisation usually was restricted to military paint and lighting. Those ordered for overseas /combat use had uprated suspension and wheels, roof and petrol can racks, etc. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Another photo in Norris’ album backs up my guess at the vehicle in the previous photograph. This is definitely a 1941 Ford Super Deluxe Woody Wagon. Here we see one of Norris’s friends pumping gas at a base motor pool pump, so possibly this was actually an RAF vehicle. Perhaps he was allowed to purchase gas from the base. If anyone has heard of a Woody being used by the RAF or RCAF, let me know. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

A photo of Arthur Norris, suitcase in hand walking through the famous gateway to Gananoque, one of the most beautiful towns along the length of the Thousand Islands. There were then and are still today, two such gateways leading into the town. Gananoque also had a substantial BCATP relief airfield that took some of the heavy traffic from No. 31 SFTS in Kingston, Ontario. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

A postcard of the same Gananoque (pronounced Gan-an-ock-way) gateway through which Norris is walking in the previous photo. Photo: HipPostcard.com

The same Western Gate to Gananoque today, heading out of town. Definitely rebuilt to accommodate a more modern highway and larger trucks, this would have been exactly where Arthur stood more than 75 years ago. Photo: Google Street View

I have always said that, no matter how short the crossing or how bad the weather, one should always get out of one’s car on a ferry and enjoy the voyage. It looks like Arthur (left) and a friend are doing just that onboard the ferry MV Quinte. The ferry leaves from a quay just 7 kilometres from No. 31 B&GS and crosses a short channel to the Loyalist Parkway (Hwy 33), the quickest route to the city of Kingston, Ontario. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

A Second World War-era photo of the ferry MV Quinte shows us exactly where Norris was sitting on the rail in the previous photograph. The 70-foot Quinte, a 12-car platform was in continuous service at Glenora from 1939 until 1974. The ferry landing at the Glenora Mills is one of the most picturesque in Ontario. Photo: RussellBrothers.ca

While sitting in the back of a stake truck rolling through town, Arthur took a photo of the Globe Hotel in Picton, which, with three ladders in sight, seems to be undergoing a renovation or at least was being painted. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

A post card from the early 20th Century showing the Globe Hotel before its renovation.

The economic impact of a nearby BCATP station cannot be overstated. When word of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan’s need for scores of new training airfields across the country got out, towns and cities from coast to coast lobbied hard to get them in their communities. The town of Picton was no exception. To start with, the station construction jobs alone could jump-start an economy still in the grips of the great depression. Settled in the 1780s by Empire Loyalists coming north after the American Revolution, Picton was named after General Sir Thomas Picton, Wellington’s Second-in-Command at the Battle of Waterloo. It was here also that Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald first managed a law practice. As with most BCATP Bombing and Gunnery Schools, Picton was chosen for its relatively flat terrain and proximity to a large body of water—Lake Ontario—to be used as an over-water gunnery and bombing range. In this photograph taken by Norris in 1941, we see a very busy Main Street, crowded with automobiles. In 1941, the population of Picton was listed as 3,901 which most certainly did not include the Royal Air Force staff and students at No. 31 B&GS. The influx of RAF personnel meant plenty of jobs at the station and increased business for cafés, retailers and movie theatres like The Regent, seen at the centre of this photo taken from the back of a station truck. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Arthur Norris would be happy to know that not much has changed in Picton’s high street in the 75 years since he was walking its sidewalks and taking in a picture show at the Regent. These days, Picton is as active and energized as it was in Norris’ time. It is the commercial centre for a strong summer tourism industry, a growing and high-quality wine region as well as a mecca for artists and artisans who operate shops on Picton Main Street. Photo: Google Streetview

The Regent Theatre still has the same neon signs and marquee that it had when Norris enjoyed its pleasures. The Regent, in its present configuration, opened its doors for the first time in 1922 as both a cinema and a live 1,000-seat playhouse, showing a Canadian production of the play Mademoiselle from Armentières. Today, it has been restored and is a regional centre for live theatre and entertainment as well as first-run motion pictures. For more on the Regent’s history watch this short video. Photo: Prince Edward County Chamber of Tourism and Commerce

The caption accompanying this photograph states simply “Wanpoo”, but I believe that this is a shot of the lads down by the St. Lawrence River at the small community of Waupoos (the word is derived from the Ojibway word “waabooz” meaning “rabbit”) on Smith Bay. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Another view of downtown Picton. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

A shot from Google Street View of where I believe the previous photo was taken in 1941 or 42. Photo: Google Maps

A Visit to Canada’s Capital

During one of the winters of Arthur’s time in Canada, he took a trip to Ottawa, the Nation’s Capital. Here he stands, as all of us Ottawans still do, on Sapper’s Bridge looking down on the eight Ottawa Locks at the northern terminus of the Rideau Canal. From here, in warmer months, commercial boats could be lowered the 80 feet to the Ottawa River. To the right of this image stands the Chateau Laurier Hotel, to the left Parliament Hill. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Standing in Major’s Hill Park along McKenzie Avenue, Norris photographs the Centre Block of the Parliament Buildings. In the valley between the snow-covered park and the heights of Parliament Hill lie the eight locks of the northern terminus of the Rideau Canal some 80 feet below. The scene has changed very little in the 75 years since then. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Standing before the Cenotaph known as National War Memorial in the centre of what is known as Confederation Square. In the background stands the Chateau Laurier, the grand Canadian National Railway hotel. The famed Canadian photographer, Yousuf Karsh, who took that most famous of photographs of Churchill, maintained his studio and home in the Chateau Laurier. As well, scenes from the motion picture Captains of the Clouds, starring James Cagney, were shot in there. Norris was also seeing the National War Memorial only a couple of years after its completion and dedication by King George VI in 1939. The memorial’s statuary had been finished in England (by sculptor Vernon March) and put on display in Hyde Park before being transported to Ottawa. On the pedestal were only the dates of the Second Boer War (1899-1902) and the First World War (1914-1818), though it was not called that then. Following the global holocaust in which Norris was then presently serving, the dates of his war (1939-1945) were added and the wars became known as the First and the Second. In 1982, it was belatedly rededicated to those who served in the Korean War (1950-1953) and then recently those Canadians who served and died in Afghanistan (2001-2014). Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

If you were the stand on this spot along Wellington Street today, you would not see anything different except the style of the cars and the low building in the distance (the Daly Building, which once housed Ottawa’s first department store) has been replaced by a condo. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Clearly, Arthur Norris had to step out into traffic on Wellington Street to snap this view of the East Block of the Parliament Buildings—taken from approximately the same spot as the previous photo. In the Second World War when gas was rationed, standing in the middle of Wellington was not as life threatening as it is today. In the distance we see Mackenzie Tower, the centrepiece of the West Block, presently undergoing extensive renovations. To the right of centre, standing on his plinth is a statue of Canada’s seventh Prime Minister, Sir Wilfred Laurier. My grandfather’s name was Wilfred Laurier Ashe, named after this man. My great grandfather was a Dominion Atlantic Railway engineer, driving Laurier’s train somewhere in the Maritimes when my grandfather was born. He learned of his son’s birth by telegraph, and then at the next station, asked to see the Prime Minister. He then asked permission to name his first-born son after the great man. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

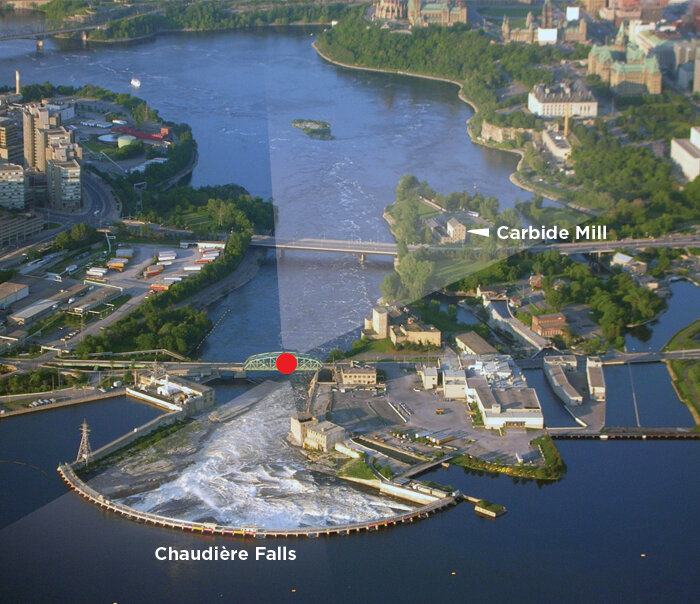

Norris photographs Parliament Hill from the Chaudière Bridge as he crosses over to the city of Hull in Québec. Beneath him run the swirling waters of the Ottawa River as it tumbles from the Chaudière Falls. The shed-roofed building in the right middle distance is the Carbide Mill (only the vertical part at the right still exists). To the right of the Carbide Mill is one of the white clapboard “Temporary Buildings” that were built to house the rapidly expanding need for government office space because of the war. Bottom: The same view today includes the modern Portage Bridge downstream which was constructed 40 years after Norris’ photo was taken. Photos: Top: Arthur Norris Collection Bottom: via Google Maps

Norris photographs Parliament Hill from the Chaudière Bridge as he crosses over to the city of Hull in Québec. Beneath him run the swirling waters of the Ottawa River as it tumbles from the Chaudière Falls. The shed-roofed building in the right middle distance is the Carbide Mill (only the vertical part at the right still exists). To the right of the Carbide Mill is one of the white clapboard “Temporary Buildings” that were built to house the rapidly expanding need for government office space because of the war. Bottom: The same view today includes the modern Portage Bridge downstream which was constructed 40 years after Norris’ photo was taken. Photos: Top: Arthur Norris Collection Bottom: via Google Maps

From where Norris was standing in the previous photo, all he had to do to take this one was cross the street and point his camera west to take in the thundering cascade of the “Chaudière”. A crescent-shaped dam holds back the torrent of the Ottawa River to extract power from it as it drops over an escarpment. The name “Chaudière” derives from the French word for cauldron or kettle. The roiling vapours, especially in the winter and spring, that hang over the falls brought to mind the idea of a kettle or “kanajo” as the local first nations people called it. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Explaining the previous two photos. To put you where Norris was standing 75 years ago on his visit to Ottawa, I composed this shot of the Chaudière Bridge with Arthur’s position in it as he turns first down river to the Parliament Buildings, then upstream towards the falls. Photo: Wikipedia

Off to Buffalo, New York

On his way to visit Buffalo, Arthur and his pals visited Hamilton, Ontario on the shores of Lake Ontario, a thriving industrial city with a magnificent business district. Today, that beautiful downtown is a much rougher area than it was in 1942. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

During his trip to New York via Hamilton, clearly the weather was not good for garden and fountain viewing as this photograph of Hamilton’s famous Gage Park testifies. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

This is what Gage Park actually looks like in more appropriate weather. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Arthur Norris’ application for entry into the United States without a passport. Back in the 1940s, Brits wishing to travel to Canada did not require a passport. And Canadians traveling to the US did not require a passport. But, undocumented people travelling to the US during wartime via Canada needed some sort of document. Five days after getting his leave from No. 31 B&GS, Arthur was given a permit to visit the United States for pleasure for “about 3 days”. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

From the back seat of a more modern car than the old flivver of their previous adventure (perhaps it is the Ford Woody wagon), Norris photographs the view as they drive across the Peace Bridge near Niagara Falls, Ontario towards Buffalo, New York. It seems likely that a mate has dropped down in the front seat so that Norris could capture the moment. In a world where most young men like Norris would never travel far from home, to be on his own with friends, travelling by car from far away Canada to New York City must have been quite the adventure. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

A photo of the famed Statler Hotel in Buffalo, New York. I suspect that this is where Norris and his buddies stayed while touring the city. With 1,100 guest rooms, three restaurants, a ballroom and numerous meeting rooms, the Hotel Statler was once the largest hotel in Buffalo, New York. Constructed in 1923, by Ellsworth Statler, it featured more guest rooms than any other hotel in Buffalo. With eighteen stories, it was the second-tallest building in the city. Hilton Hotels purchased the hotel in 1954, and it became known as the Statler Hilton. Today, the lower public spaces are still operating as Statler City, while plans are being made to create condos on the upper floors. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

In the upper photo, the magnificent art deco bulk of Buffalo’s City Hall looms over Norris during his trip to that city. In the lower shot, the building as it is today. Photo: Top: Arthur Norris Collection, Bottom: Wikipedia

A Visit to the Big Apple

In August of 1942, Arthur (right) and a few of his Picton pals made another, deeper foray into New York State, this time to New York City itself. Here, in their tan summer uniforms, they pose before the Statue of Liberty. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

During his stay in New York City, he did what many touring military men with an intimate knowledge of troopships might have done that summer—visited the capsized wreck of the SS Normandie. He photographed her surrounded by scrappers’ barges, having already lost her superstructures. Normandie had sought safe haven in New York in 1939 as the war situation in Europe grew more ominous. When war broke out in September, the Americans interned her as neutral countries do to prevent her from being used in the war. In December 1941, five days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Americans removed the French captain and crew (who no doubt were living in the lap of luxury) and took possession of the massive ship under “right of angary” and renamed her USS Lafayette. She then began a rushed conversion to a troopship—removing the luxury components, mounting of guns and painting her grey. On 9 February 1942, sparks from welding ignited a stack of flammable life jackets and started a fire that spread quickly. The fire raged throughout the day with fireboats and firemen on shore pouring so much water into her hull, that she began to list. During the following night, she capsized. Arthur’s photos were taken just five months later. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Another photo by Arthur Norris shows the massive 982-foot hull of Lafayette. After the hull was righted in August of 1943, she was towed to a berth, there to await further conversion as an aircraft transport and ferry. After assessing the damage to her hull and equipment, the US Navy decided it wasn’t worth the effort and laid her up until the end of the war. She was broken up for scrap in New Jersey in 1948 by Lipsett Inc. There are many great videos of the fire, the salvage and the scrapping on the web, and I highly recommend you watch them as this is an astonishing end to one of the most beautiful ships ever designed and built. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

The day of the fire and the day after the fire. Photos: via the web

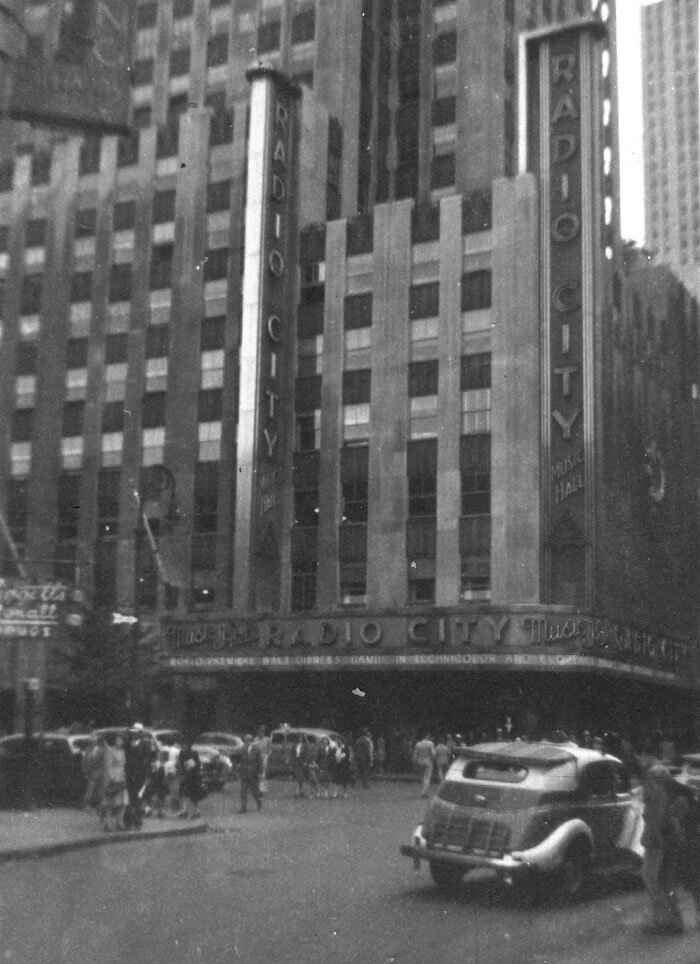

Norris stands on West 50th Street to capture the marquee of Radio City Music Hall, no doubt there to take in a film and a performance by the leggy Rockettes chorus line. The marquee and hall have not changed at all since the war, though a quick look on Google Street View will show you just how colourful this corner really is. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

The caption on the back of this Norris photo reads “RCA Building”, or as we know it, Rockefeller Centre. Here, he stands in the middle of the Channel Gardens looking toward, in the distance, the famous golden statue of Prometheus on Rockefeller Plaza. At the very back is the RCA Building. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

A modern view of where Norris was standing when he took the previous photograph.

A classic shot of Times Square with pretty girls, skyscrapers and plenty of bustle. The Loews State Building on the left was the headquarters for MGM motion pictures, while across the street, Gary Cooper in the Pride of the Yankees, the story of famed baseball player and unfortunate namesake for ALS, Lou Gehrig, is playing at the Gaiety Theatre, while the Hotel Astor looms at the right. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Arthur Norris stands at the corner of East 50th Street and Madison Avenue, looking towards the unmistakable limestone monolith that is the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center (now the GE Building) in the distance. One can only imagine how thrilling this must have been for a young man from England where skyscrapers had not yet taken root and who, because of the war, was visiting a city he otherwise may never have visited. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Arthur Norris stands in Riverside Drive (The stone wall is still there) in Hudson Heights, Upper Manhattan to take this picture of the then 10-year-old George Washington Bridge spanning the Hudson River to New Jersey. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

The Motor Pool in the Motor City

At first, I did not recognize which city this was, but the radiating avenues hinted at Detroit. A close look at signs in the photo tells us for sure that it is Detroit. In the centre you can read Detroit Leland on the roof of one building, while at bottom, the Hadley Finsterwald Co. department store at 219 Michigan Avenue sign is also a dead giveaway. In the lower right is the mass of the Book-Cadillac Hotel, now a Westin Hotel, while the tower at upper right is the stunningly-detailed 36-storey, Italian Renaissance Book Tower. The bulky 19-storey building at centre-left was then the SBC Building on Cass Avenue and is today the Michigan headquarters of ATT. The Detroit Leland Hotel at centre is still operating—at 90 years old, the oldest continuously operating hotel in downtown Detroit. What is truly amazing is that most of these historic architectural gems are still in existence despite Detroit’s hard times. There is no doubt that this photo was taken from the observation deck of the Penobscot building, then the highest in Detroit. For a news article about that observation deck re-opening recently and a look at just where Norris was standing when he took the photo, click here. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

The 36-storey Union Trust Building (now called the Guardian Building) in Detroit as photographed by Arthur Norris from an even loftier height—the observation deck of the Penobscot Building. The Union Trust Building is recognized as one of the finest art deco architectural masterpieces of the 1920s. Hidden by bright reflection in the upper right is the Detroit River. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Norris takes a dramatic shot of Campus Martius Park in Detroit with the majestic Michigan Soldiers and Sailors Monument in the centre right. I think this is from another building than the Penobscot Building, possibly his hotel room but I may be wrong. The park is at the confluence of four avenues in Detroit—Monroe, Woodward, Michigan, and West Fort. Of the buildings in this scene, including the one from which he is shooting, only the building at upper right remains today. This park was the centre of a very prosperous and upscale Detroit when the automobile was king. For Ford and GM truck and vehicle drivers like Norris and his friends, this must have been like a pilgrimage to Mecca. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Off to Southeast Asia

In May of 1943, after years in Ontario, Arthur Norris was transferred to the China–Burma–India Theatre of War. As he was getting set to go in June, Arthur collected the names and addresses of fellow RAF and RCAF airmen who he had gotten to know in Picton. In his note, W.A. Gamble poignantly writes: “Maybe I shall meet you in Blackpool some day and when I do, I shall tell you to “get your Canadian hours in” Alright.” It seems they never did meet again. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

It seems to me that every base, every barrack in fact, had a gifted illustrator who could draw in the flourishing cartoon style of the day. I can’t read this fellow’s name, but he offers up this loving sentiment on the opening page of Arthur’s autograph book: “I write this first page to you, Arthur, and hope it brings you luck, also health and happiness always. I do not want to say Cheerio! Because I feel sure we shall meet again in “Blighty”, and again share the happiness we found in Canada”. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Here, a George Pasfield of Romford, Essex writes promisingly: “You leave me here. We say goodbye. But we’ve met before. And we can do it again.” I tracked one record of two Pasfield brothers, John and William, who lived at 81 George Street, Romford, Essex and apparently both were killed in the First World War. Sacrifice in war was evidently great in George’s house. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Arnie from Ravensthorpe, an area of the city of the industrial city of Dewsbury in North Yorkshire, England writes: “We’ve been together for quite some time and now that the time has come for us to part, I’m sincerely hoping that we shall meet again. All the very best.” Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

They may have been young inexperienced lads when they left England for Canada in 1941, but two years later, they were seasoned travellers and men of the world, as well as experienced drinkers. A.W. Terry, a Canadian boy from Toronto, pens a poem for Arthur: “Little drops of Whiskey. Little drops of Beer. Make you see white Elephants if you percevier.” (I imagine he meant persevere). As life would have it, it was only the Terry family who would maintain the connection with Arthur after the war, for it was Terry’s parents who became a second set of parents for Arthur during his time in Canada, with Arthur staying at their home on Woborn Avenue in Toronto from time to time. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

Arthur (right) and a friend pose in their Southeast Asia kit at the Worli Transit Camp near Bombay on their way to Burma. Airmen and other service personnel coming to the China–India–Burma Theatre of War passed through here after debarking their troopship, sometimes languishing for months. Arthur seems much older now or perhaps just exhausted from the heat, the travel and being away from home and family for years. While in Burma, Arthur taught the locals how to drive. Photo: Arthur Norris Collection

The last known photograph of Arthur Norris, taken in 2015 at the age of 95. He holds his newborn Great Granddaughter Eva in his arms. No happier place to leave the story than right here. Photo via Mike Norris