AT YOUR SERVICE ANYWHERE

First Published April 1, 2015

Prologue

These days, we look upon aerial refuelling as the purview of the world’s largest air forces—a force multiplier, a reach extender, a vital link in the projection of force. But it was not always this way. In the beginning, the earliest experiments in the now refined yet complicated aerial dance called air-to-air refuelling were carried out by civilian pilots and business people looking to lengthen the range of aircraft and thereby shorten the length of time required to travel long distances. Long distances required multiple stops for refuelling, and by extending range, flights could be shortened in overall duration. These early experimenters were not in the game to create a commercial enterprise out of refuelling, though that would come decades later. They were expanding the capabilities and the importance of a new and emerging field of endeavour—commercial air transport.

As the world of powered flight rolls through its twelfth decade, the early pioneers of flight, who risked their lives to blaze new trails; to do what had never been done before or who designed far out on the leading edge of creativity; have long since faded into history. The photos and images of those days seem so ancient and distant, well out of our own memories and lifespans. To have the opportunity to talk with one of aviation’s pioneers in a chance meeting was an honour that made me more fully understand that aviation is still, today, a young field of endeavour.

December 1991

Three weeks before Christmas, I flew to Gulfport, Mississippi where I joined up with close friend Lieutenant Colonel Greg Williams for a flight north to Key Field in the small Delta city of Meridian. Key Field was the home of the 153rd Tactical Recon Squadron, 186th Tactical Recon Wing of the Mississippi Air National Guard (MS ANG). For three decades, the MS ANG, or the Magnolia Militia as they called themselves, had been flying McDonnell RF-101 Voodoos and then RF-4C Phantom fighters, training in the art of low-level reconnaissance. It was one of the last of the wild and happy fighter flying clubs of the Cold War. But that was about to change.

The reason I was there was to witness the last weekend of Phantom operations for the squadron of “weekend warriors” before they transitioned to the less-than-exciting KC-135R Stratotanker and ceased to fly “upside down with their hair on fire” forever. Williams told me “It’s like driving a Ferrari all your life and just when you got really good at it, being asked to drive a school bus instead.” It was both a joyous weekend and a sad one. It was a weekend of thundering takeoffs and endless touch and goes as pilots and their soon-to-be-extinct Weapons Systems Officers (Whizzos) stretched their last flight out until only fumes were left in their tanks. It was a weekend of unsurpassed noise, kerosene stink, engine heat and high-test mixed drinks.

At the end of the weekend, they would begin flying their “Rhinos”, with their squadron markings removed, to the boneyards of Davis Monthan Air Force Base—later to be used as target drones or more likely broken up. Soon, many of the old whizzos faded away, and the pilots flew off to Tanker School. It was a difficult time for the old guard of hard-ass fighter boys, but “going to tankers” was a smart political decision on the part of squadron commanders who had much more to think about than the personal preferences of a bunch of boy pilots. In those days (and today still), an Air Guard base was a large economic driver for the community in which it operated. Flying fighter aircraft employed plenty of pilots and whizzos, but with the air force downsizing, taking on the tanker role would guarantee the future of the “business” and employ more people. The old guard was not delighted, but everyone understood.

Towards the end of the weekend, Greg and I were invited to 186th Wing Commander General Bob Soulé’s home in the surrounding suburbs for a party celebrating his daughter’s recent marriage. It was a typical winter night in Mississippi—warm by Canadian standards. The trees were ablaze with Christmas lights as we swept up in a big old Lincoln Town Car with open alcoholic drinks in our hands (legal in Mississippi) and were greeted warmly by Soulé at the door. There is something incredibly grand and gracious about a Southern welcome that is incomparable. You are instantly at ease and part of the family.

Entering the kitchen, I was handed a glass of champagne and then made my way towards the living room. Scanning the happy crowd of guests, I noticed right away an elderly gentleman who was holding a book which I had designed a few years back and had given to Soulé. He was smiling ear to ear and he was looking straight at me. Something about the twinkle in his eye that said…“I need to speak to you.”

He introduced himself to me as Bob Soulé’s Uncle James and the stories he was about to relate were astounding in their historical context and coincidence. Intrigued by the fact that he was holding a copy of my book, I asked him if he had read it. “Sure have, but that’s not what I wanted to tell you. I love Canadians and I have a long story to tell.”

Uncle James was James Keeton, a Continental Airline pilot for most of his entire professional career, flying the Boeing 257, DC-3, DC-6, DC-7 and Boeing 707. He smiled as he recounted his days with Continental. Of all the aircraft he flew, he enjoyed the elegant 707 jet more than any and had some harrowing experiences flying grunts to and from Saigon during the Vietnam War. Continental had a long-term contract to ferry the soldiers and Uncle James told me some exciting stories of extreme angle dives with the 707 into Ton Son Nhut Air Base. If he thought it was terrifying, imagine the poor bastard FNGs in the passenger cabin.

One day, as Bob Soulé (who claimed he had more combat hours asleep than awake) was orbiting his Lockheed EC-121 Constellation off the coast of Vietnam, he heard radio transmissions from a Continental Airlines 707 heading back to the US from Saigon. “Ya’ll wouldn’t happen to have a Captain James Keeton on board, would ya?” he radioed. “You bet, he’s sitting right here beside me,” came the reply from the First Officer. Somewhere out over the South China Sea, going in different directions on a dark night, they chatted with their wonderful Southern drawls and warmed each other’s hearts so far away from home.

These stories had me enthralled and the champagne was flowing when Uncle James pulled a folded photocopy of a letter from his vest pocket and handed it to me. It was addressed to James Keeton of Magnolia Springs, Alabama from Donald B. Rice, Secretary of the Air Force and cited him for his substantial contribution to the development of aerial refuelling, especially in light of an astonishing accomplishment in 1935 and its bearing on the new role of his nephew’s squadron.

The letter, which he let me keep, read…

“Please accept my personal thanks for your participation in the historic return of the midair refuelling mission to Key Field, Meridian, Mississippi, on February 8, 1991. Your pioneering spirit during the record breaking flight in 1935 has had a direct and lasting effect on American air power. The efforts put forth by you, A.D. Hunter, Bill Ward, and the Key Brothers changed the course of aviation history.

Many lives and aircraft have been saved as a result of aerial refuelling. Today tanker aircraft are refuelling other aircraft safely, reliably and routinely on an almost continuous, worldwide basis. The force multiplier represented by our nation’s aerial tanker fleet makes American air power premier among nations. The deterrence provided by the Strategic Air Command’s long-range bomber aircraft is directly enhanced by their ability to be refuelled while airborne. Your contributions toward the development of aerial refuelling have kept ours a free nation.

For your past efforts, as well as your continued interest in American airpower, I salute you on behalf of all the men and women of the United States Air Force.

Best regards, Donald B. Rice”

It seems that, in 1935, a world’s record for endurance in sustained flight was established by two brothers from Meridian—Algene and Fred Key. Al and Fred took to the air in a Curtiss Robin monoplane at 12:32 PM on 4 June and did not come down to the ground for another 27 days. The Robin, nicknamed “Ole Miss,” was equipped with a catwalk outside the cabin that allowed Fred or Al to step outside to service the aircraft in flight. In addition, a large hatch in the roof allowed them to collect food, water, news and most importantly gasoline—from a hose lowered to them from a second aircraft flown by Uncle James with a second pilot, Bill Ward handling the refuelling hose. The hose was equipped with a special patented nozzle with a cutoff valve that had been designed by A.D. Hunter. This basic design is still in use today, hence the enormity of the impact the Keys and Keeton had on refuelling history.

At the time of their accomplishment with the Key Brothers of Meridian, Mississippi, these two men were the most experienced aerial refuellers in the world. James Keeton (left) and Bill Ward flew another Curtiss Robin monoplane and made more than 100 aerial rendezvous with the Key Brothers in Ole Miss. Keeton did all the flying, while Ward handled the refuelling and the resupply. They used a hose with a specially designed nozzle and connector which shut the flow of fuel in the event of a disconnect, which happened many times. That basic design was the type used by USAF KC-97 Stratotankers and is still in use today. Photo via flyhistoricwings.com

Related Stories

Click on image

Algen and Fred Key, decked out in their snappy Key Brothers “Flying Keys” uniforms. Photo via flyhistoricwings.com

For over 27 days, in all kinds of weather, they circled the Meridian airfield, always in sight of the official observers on the ground with Keeton and Ward going aloft over 100 times to replenish, fuel, oil and food. The flight lasted 653 hours with the tiny aircraft logging an astonishing 53,000 miles (more than twice around the world at the equator) without stopping.

Upon landing, George W. Schneider, manager of the motor overhaul department of Delta Airlines, was named by Wright Aeronautical Corporation to inspect the motor thoroughly. Astonished by his first figures he again micrometered all parts of the motor. The wear on all parts was minimal despite no spark plug changes. New exhaust valve guides and a new set of rings were the only replacements necessary to put the engine in first class condition.

Fred Key, tethered to Ole Miss, walks out on the catwalk to do some preventative maintenance on the engine. Photo via itinerantneerdowell.com

Today, the Key Brothers’ Curtiss Robin Ole Miss hangs in a place of honour at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington DC. Mannequins demonstrate exactly how maintenance was achieved during the flight, with Fred Key walking out on the catwalk, securely tethered to the aircraft. Photo National Air and Space Museum

While their air-to-air record was achieved as civilian aviators, Algene (left) and Fred Key became military fliers when the Second World War broke out. Both men flew multi-engine bombers. Fred received a Distinguished Flying Cross (American) and Al became the commanding officer of a Liberator unit (66 Squadron, Eighth Air Force) with a DFC, a Distinguished Service Order (American), DSO (British), and seven Bronze Stars. Photos: Wikipedia

So, Algene, Fred, Bill Ward and Uncle James made history, Meridian’s airport became Key Field, and the 153rd became an Aerial Refuelling Squadron nearly 60 years later. “What goes around comes around,” said Uncle James, smiling proudly.

“But what does this all have to do with Canada?” I asked, more curious than ever. “How old do you think I am?” he asked, seemingly out of the blue. When you are in your early forties as I was, you are a bad judge of senior years, but I answered quite honestly—“What, about 65, 70?” He smiled again, delighted. “Eighty-one” he answered, beaming good spirits. There was no doubt he looked a lot fitter than an octogenarian should. “I feel fit and happy and I owe it all to Canada. Or rather to the Royal Canadian Air Force!”

Since the early 1960s Keeton had been doing daily exercises, following the world famous 5BX and 10BX programs of the RCAF. Five Basic Exercises (5BX) and its later development 10BX became the world’s first exercise craze. Twenty-three million copies of the booklet were sold to the general public worldwide and the text translated into 13 different languages. My father-in-law, a retired Wing Commander in the RCAF, was still using it daily as well.

“How did you learn about 5BX?” I asked. At this he smiled wider than before. And the real story he wanted to tell me came out. But I am getting ahead of myself.

Supertest Petroleum’s Mid-Atlantic Aerial Refuelling Project (MAARP)

On 27 July 1949, the beautiful de Havilland DH.106 Comet took to the skies for the very first time—the world’s first jet-powered airliner. While the uptake was slow, and in the case of the Comet, fraught with setbacks, the world took notice of the writing on the wall. Jets could fly higher and faster than the piston-pounding propliners which would dominate the next decade of transatlantic airliner service, but the public was slow to be convinced of a jet-powered future. Nearly a decade later, in 1958, the iconic Boeing 707 would begin scheduled service with Pan American World Airways and the number of gas-powered, propeller-driven airliners operating over the Atlantic began a steady decline to oblivion.

At the time of the first flight of the Boeing 707 in December 1957, the airlines of the world had a massive financial investment in such classic propliners as the Boeing StratoCruiser, Lockheed Constellation, Canadair North Star and Douglas DC-6 and 7. Airlines were naturally cautious about jet-power, but they could see that the public was beginning to see the glamour of jets and especially the Boeing 707. Many small and medium sized operators took a wait-and-see attitude, having invested heavily in piston power.

The problem was that all airliners of the day, including jets, had relatively “short legs” and had to refuel before beginning their over water crossing and even immediately afterward. Europe-bound airliners out of the Eastern Seaboard of the United States and Canada needed a pit stop in Gander, Newfoundland and another in either Prestwick, Scotland or Shannon, Ireland. Those airlines bound for Mediterranean destinations needed to put down in the Azores for fuel. This added hours to the length of the journey, but jet travel was now holding out the promise of flying faster between fuel stops, thus shortening travel time and attracting passengers to jet-equipped airlines.

In the mid-1950s, the RCAF itself was running a scheduled jet-liner service with their newly acquired de Havilland Comets. Piston-engine commercial operators were reluctant at first to dump their investment in propliners until jets could prove themselves and so some saw an appealing alternative solution when Canada’s Supertest Petroleum advanced their Mid-Atlantic Aerial Refuelling Project (MAARP) to the test stage.

Supertest was a medium-sized Canadian petroleum company that had been growing successfully since 1923, focused largely on automotive gasoline, but with an aviation fuel division that had been supplying 100 octane avgas across Canada. Supertest was promoting its high octane gasolines by sponsoring an unlimited class hydroplane race boat by the name of Miss Supertest and had seen huge success—not just Harmsworth Cup victories, but tremendous national brand awareness. The Miss Supertest race boats (Miss Supertest I, II and III) relied on avgas to power their aircraft engine power plants (Rolls-Royce Merlins and Griffins.)

By the mid-1950s, Supertest’s board of directors felt the margins in high octane avgas were much higher than jet fuel (basically kerosene) and therefore far more attractive in terms of a business focus. A fall-off in the use of 100 octane fuels would seriously jeopardize their massive investment in refining facilities near Sarnia, Ontario. They had tasked the company with finding solutions to the problem posed by jets. Could a means be found to extend the range of piston aircraft and counter the speed of jets? The answer was air refuelling.

The MAARP concept had been under development from 1956 to 1958, and by 1959, Supertest’s board liked what they saw and gave the green light to company executives to proceed to a working test of the concept.

This would involve the lease of two KC-97 Stratotankers from Boeing in Seattle and the fitting up and training of civilian crews by units of the United States Air Force. The USAF and the American government were themselves interested in extending the life of their considerable piston assets. A period of diplomacy ensued, resulting in permission by the office of James H. Douglas, the Secretary of the Air Force, to allow civilian pilots and tanker crews to be recruited in Canada but trained by experienced American tanker crews. An air refuelling unit based at Newfoundland’s Harmon Air Force Base would do the training and all of the training flying would be done in Canadian or international airspace.

The Supertest staff tasked with developing the concept travelled to Washington to speak to Pentagon brass about air refuelling, its costs, complexities and even its history. At that point the concept was more than 20 years old, but to reassure cautious potential customers and future passengers that there was nothing risky about a civilian air refuelling system, they met with and later recruited James Keeton, a Continental DC-7 piston airliner pilot who pioneered the concept in the skies of Mississippi two decades before.

The concept went something like this: Out over the Mid-Atlantic Ocean, close to the main flying routes and 24 hours a day, Supertest KC-97 tankers would orbit in 100-mile east-to-west racetrack patterns. There would be one “service station” on the Northern route and one in the South. Each “station” consisted of a pair of KC-97s flying opposite sides of the pattern, one flying east, the other west, and alternating after the turn. Contracted piston airliners would refuel from the tanker heading in their direction, then fly on to the original destination. These tankers would be relieved by fresh tankers and crews after an eight-hour stint in the racetrack, refuelling contracted airliners in fight. The concept required a tanker base in the east (Spain was a likely candidate) and one in the west (possibly Long Island) and a minimum of 20 tankers to make the system work.

It was also thought that MAARP tankers could offset a percentage of their operating costs by carrying paying passengers at hugely discounted prices. While this was not for everyone, it was built along the same business model as passenger space on cargo ships—an adventure for someone with time on their hands and a lack of concern for “frills”.

For about one third the normal price of a transatlantic fare, passengers would board a tanker at Idlewilde, fly to the mid-Atlantic and stay “on station” for eight hours before being relieved to fly on to Spain or wherever. Passengers would have plenty of leg room and be offered the same boxed meals as were supplied to the crews. There was no smoking as on other transatlantic flights. Passengers would have to endure bad smells, bad air, incessant noise, bland food, no service, poor heating, and long delays—roughly the equivalent of modern passenger travel, but with more leg and head room and deep discount prices. Supertest had by now applied for a commercial carrier license. Aircraft might pick up passengers in New York as any airliner might, then fly out over the Atlantic, complete an eight-hour racetrack circuit, and after relief, fly on to London to offload passengers. Aircraft requiring service would fly on to Spain or wherever the base would eventually be situated. Crews would live at this base along with maintenance staff. It would be an arduous journey for passengers, but with the right price, it was felt that there would be a market.

Supertest had what they felt was solid interest from a number of smaller transoceanic airlines like Scandinavian, Trans Canada, Avianca, Overseas National, Wardair and others. No one wanted to commit to the aircraft upgrades and mods required or the costly flight crew training until Supertest could successfully demonstrate the viability of the concept. So the company jumped in with both feet.

In July of 1959, Supertest took delivery in London, Ontario of two refurbished KC-97s with all secret military radios and equipment removed, but with the latest in flying-boom air refuelling systems. Supertest was offered the latest model KC-97L tankers which had a pair of turbo jets—one on each wing outboard of the piston engines—but declined as they would have to use jet fuel from another company.

A great shot of Boeing KC-97 Superstratotanker Pepe Lemieux (52-2781) flying over St. George’s Bay, Newfoundland during crew training at Harmon AFB, Stephenville. While the Newfoundlanders were a bit apprehensive about the jobs that would be lost in Gander should the project be a success, they nonetheless welcomed the Canadian crews of the Supertest tankers. Following the end of the Superstratotanker experiment, Stratotanker 55-9595 was returned to the United States Air Force and then assigned to the Wisconsin Air National Guard, where it was flown on occasion by EAA founder Colonel Paul Poberezny. Photo: USAF

Known as Stratotankers to American KC-97 crews, Supertest called them Superstratotankers, and their Canadian crews nicknamed them “Flying Gerry Cans”, or even “Gerries”. The two aircraft arrived with full corporate markings having been applied at the Boeing plant in Seattle. Each aircraft was dedicated to an individual whose name was worn on the side. KC-97-01 carried the name of a hero of the Supertest Petroleum Company—Todd “Pepe” Lemieux was a legendary company wildcat driller who discovered the highest-producing well in Supertest history. He was killed a short time later whilst saving the lives of his drill rig crew. The other was dedicated to James Keeton in recognition of his pioneering work in aerial refuelling. Keeton would also take part in a promotional tour with the first trained crew.

One of the two Superstratotankers leased by Supertest (52-2781) was named after deceased and legendary Supertest wildcat drilling foreman Todd Pepe Lemieux. Lemieux (centre front row) is seen here with the drilling crew that found Grand Coq No. 3 in the Turner Valley—the highest producing crude oil well in Supertest history. His best friend and preferred rigger, Bruce “The Uke” Evanchuk (left front row) said of his drill foreman, “That f----r could drill the arsehole out of a rat snake from twenty thousand feet wearing a blindfold and still find viable snake oil!” It was at Grand Coq that Lemieux was killed shortly after the discovery when a blow-out sent three forty foot lengths of drill pipe a hundred feet in the air following a blow-out preventer malfunction. His rigger and floor hands were momentarily stunned and deafened by the concussion and did not see the pipe blow out of the ground. Lemieux pushed the three men on the floor out of the way before the pipe returned. Unfortunately he slipped on the oily deck and fell face first. A length of returning pipe skewered him like a perogie on a fork to the platform, killing him instantly. His last words were: “That’s going to cost the company.” The resulting fire from the blow-out lasted more than six weeks and became known as the “Devil’s Zippo”. The Uke suggested that Supertest name the tanker after Lemieux, explaining that the fuel we’ll be pumping will more than likely come from his Grand Coq. Evanchuk became one of the first class of new civilian boomers trained by Supertest—a tribute to his old friend. Photo: history.alberta.ca

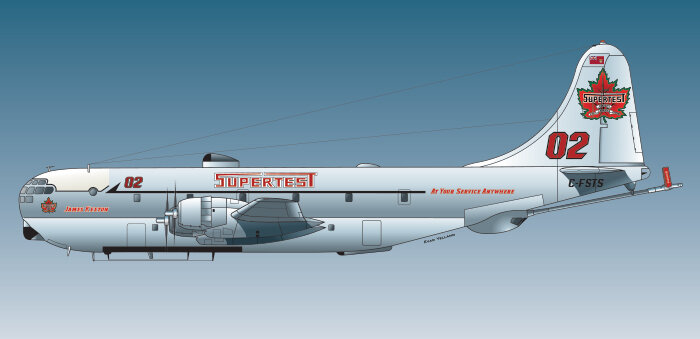

Boeing Superstratotanker KC-97-02 (53-0189) James Keeton during a training flight from Harmon Air Force Base in Stephenville, Newfoundland. Crews, including Canadian and American pilots and all-Canadian boomers, navigators and flight engineers were trained by the USAF’s 376th Air Refuelling Squadron based at Harmon. Following the failure of the Supertest Mid-Atlantic Air Refuelling Program, James Keeton would be upgraded by Boeing to a KC-97L with the addition of podded turbo-jets outboard of the radials. Stratotanker 53-0189 would then be sold to the Spanish Air Force where it served with Escuadrón 123, Ejército del Aire. Photo: USAF

A profile of Supertest’s Superstratotanker No. 01 (C-FSUP), known as Todd “Pepe” Lemieux, or simply Pepe Lemieux. Profile by author Yellamo

A close-up of the Pepe Lemieux, with cartoon nose art of Pepe Lepew, the amorous Parisian skunk. Lemieux earned his sobriquet for his amorous pursuits—“Laying pipe is my life—on and off the job,” he was fond of saying. Profile by author Yellamo

A profile of Supertest’s Superstratotanker No. 02, (C-FSTS) known as James Keeton, or simply the Jimmy K. Profile by author Yellamo

Detail of the James Keeton. Profile by author Yellamo

Following a national press conference and VIP event on 12 July where Canadian flight crews and boomer candidates were introduced, the two tankers were fired up by their American ferry crews and flown to Stephenville on the west coast of Newfoundland where they would be stationed during a year-long training period for new flight crews and boom operators. The crews, including 12 boom operator candidates selected from applications made by Supertest employees, travelled by train a week later.

Flight crews were mostly former RCAF pilots, navigators and flight engineers along with a few Americans with tanker experience. The United States Air Force in the form of 376 Air Refuelling Squadron based at Harmon Air Force Base would assume the training duties as well as general maintenance (for which Supertest Petroleum would be billed) and provide hangarage, accommodations and messing. All flight and refuelling training was to be carried out in Canadian or international air space

A rare shot of the two Supertest KC-97s together at Harmon Air Force Base as company tanker trucks arrive to refuel them. Photo: USAF

The United States Air Force and United States Navy provided Lockheed C-121 Constellation aircraft when required as receiver aircraft for training purposes. Training continued apace throughout the rest of the summer and over the winter. Pilots, navigators, engineers and boomers trained and lived on the base throughout the winter and began to coalesce as crews as the weather lifted in the spring. Part of the reason for training at Harmon Air Force Base was its proximity to the Atlantic and its capricious and sometimes angry weather. Supertest planners wanted their training to be thorough and in conditions similar to those they would expect during real operations. Pilots and flight deck crew also spent numerous hours in a KC-97 simulator when the blizzards of a North Atlantic winter prevented them from flying.

Supertest employed a KC-97 simulator at Harmon AFB to train flight crew. Here the front of the cockpit has been removed so that cameramen can get a better view for publicity shots. All flight crew were required to wear the same orange uniforms and patches that service station attendants across the country wore. This was hard to swallow by pilots who thought they were a higher life form. Photo: USAF

A great shot of Supertest KC-97 James Keeton and her crew working up with a United States Navy Lockheed Constellation at Stephenville, Newfoundland in March 1960. Photo: USAF

Throughout the winter, Supertest’s advertising and marketing agency Bayer & Zeller were busy putting together a promotional campaign they felt would convince regulators and airline executives that the concept was the answer to their piston-powered prayers, sell more automotive gasoline and put Supertest on the world stage as an innovator and a household name.

The campaign had three major components. At the consumer level, Supertest advertising throughout the winter featured the project and made the connection between the powerful gasoline in the family station wagon and that aboard a Trans Canada Airlines Super Constellation. Supertest, which had always proudly stated that it had the “Finest Pump-side Service in the Dominion,” now ran with the tag line “At Your Service—Anywhere!”

Across Canada, Supertest Service Stations (“On the Ground and in the Sky” went one advert) offered a “Skyburst of Bonuses”—giveaway premiums to thrill the kids, such as a plastic KC-97 vertical stabilizer that could be attached to the family car, a refuelling probe receptacle decal for the roof of the car and a pair of Supertest pilot wings identical to those worn by Superstratotanker flight crews. Also available were highball and shot glasses with the silhouette of a KC-97 refuelling a propliner.

Supertest Junior Pump Pilot wings. These inexpensive plastic wings with pin-back were popular with Canadian kids during Bayer & Zeller’s promotional campaign. Today, they are a petroleum advertising collector’s holy grail. From the collection of Albert Prisner

Gasoline and service sales across the country skyrocketed and the company was getting tremendous attention from the media. One television advertisement featured a fellow in a family car positioning himself behind a flying KC-97 and the driver cheerfully shouting out the driver’s side window “Filler up Joe—gas!” As he does, his hat is swept away in the wind and the camera cuts away to reveal that he is flying/driving an Aerocar flying car. The slogan “At Your Service Anywhere” then comes flying out at the viewer as the boomer (Gus Gazzler) tips his hat to the driver and the Aerocar and KC-97 bank away in opposite directions. The commercial aired on Hockey Night in Canada and received an overwhelmingly positive response.

Bayer & Zeller put together a complex promotional goodwill tour that would include stops in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, Detroit, Windsor, Toronto, Ottawa and Montréal. The USAF did not want to be seen to be connected with a Canadian project so declined to appear with one of the KC-97s, but Eastern Airlines, which was a possible future partner with Supertest, lent the tour a Lockheed Constellation crewed by ex-military fliers to perform paired up flypasts for dignitaries. The Connie had no refuelling capability, but the flypasts were very convincing. KC-97 James Keeton travelled with the Eastern Constellation for all the American stops and both aircraft made national news and headlines in every city they visited.

The star of the show was none other than Uncle James Keeton himself, who was recruited to accompany the tour, flying the now more than thirty-year-old Curtiss Robin “Ole Miss.” The stark juxtaposition of her fragile tiny airframe and the Will Rogers-like character of James Keeton with the sleek behemoths of modern technology really hit home to the public that air-to-air refuelling had come a long, long way. Keeton’s role in the tour stopped at the Canadian border and he turned the little airplane around and flew it to Washington where it was accepted as the national treasure it was by the Smithsonian.

Eastern Airlines would loan a Lockheed L-049 Constellation airliner (N86516—actually a wet-leased TWA ship) for the American portion of the Supertest Superstratotanker promotional tour of 1960. Supertest had permission to replace the Eastern titling and winged bird. The promotional tour which featured a recently-modified Stratotanker (the Pepe Lemieux) also involved James Keeton flying the famous Key Brothers’ Ole Miss to destinations across the Eastern Seaboard for appearances together. Here we see the two aircraft together on the ramp at New York’s Idlewild Airport prior to a press conference with Mayor Robert F. Wagner and famed First World War fighter ace Eddie Rickenbacker, Chairman of the Board of Eastern. Though there were dignitaries aplenty, it was James Keeton that stole the show with his relaxed demeanour, common sense and Alabaman charm. He made headlines when he quipped: “New York’s a fine place with fine people, but they are sorely missin’ some boiled peanuts, what we in Pickens County call Country Caviar.” Two days later, Eastern shipped 100 cases of the finest Hardy Farms boiled peanuts, and they were served at all the goodwill tour stops after New York—Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, Detroit, Windsor, Toronto, Ottawa and Montréal. Photo via itinerantneerdowell.com

Supertest Petroleum billed itself (if somewhat redundantly) as “Canada’s All-Canadian Company” and in this much-publicized shot taken during the Superstratotanker’s 1960 publicity tour, it is well and truly all-Canadian. In the foreground, Bob Hayward pilots Miss Supertest III, the company’s famous, record-holding and three-time Harmsworth Cup winning hydroplane. The photo, taken on the Ottawa River below RCAF Station Rockcliffe during Air Force Day celebrations, shows Superstratotanker KC-97-02 James Keeton leading an RCAF Canadair North Star transport from 412 Squadron, flying out of RCAF Station Uplands. The North Star was “borrowed” for the day by Supertest to demonstrate how the RCAF might one day use Superstratotankers to speed up the crossing of the Atlantic. The North Star had no air-to-air refuelling capability, so this flypast was solely for show. By this time, however, 412 Squadron de Havilland Comets had been flying scheduled jet service across the pond since 1953. Both the North Star and Miss Supertest III were powered by the Rolls-Royce Merlin V-12. Sadly, Hayward was killed in 1961 piloting Miss Supertest II, a month after winning a third straight Harmsworth Cup in Miss Supertest III. Photo: Wikipedia

On the Canadian cities of the tour, Supertest utilized their sponsorship of the Harmsworth Cup-winning Miss Supertest III (powered by an aircraft engine) to team up for a series of publicity “air and water flypasts” featuring KC-97 James Keeton, Miss Supertest III and an RCAF North Star from RCAF Station Uplands. On the waterfronts of Windsor, Toronto, Ottawa and Montréal, the three thundering giants drew massive crowds and priceless publicity. Canadians were still smarting from the Avro Arrow cancellation and the near fatal blow to the Canadian aircraft industry and national pride. To see a new aerospace story rising before them gave hope for a renewed place for Canada in the pantheon of the great aviation countries of the world.

Bayer & Zeller also arranged for press coverage of these activities, and one story truly captured the imaginations of Canadians. Popular female reporter June Callwood, writing for MacLean’s magazine after the end of the publicity tour, travelled aboard the James Keeton as it returned for more training at Harmon AFB and spent three days with the crews covering their training. The result was a front cover and an 8-page feature that really made popular heroes of the men who were training for the MAARP program.

There wasn’t a Canadian alive who didn’t know about the project and Supertest gasoline sales continued to soar. It was the single most successful promotional campaign in Canadian automotive history. The MacLean’s article by Callwood won a national reporting award and air shows from coast to coast were trying to sign up the Superstratotankers for appearances.

In the summer of 1960, at the request of Supertest Petroleum, one of their largest advertisers, the iconic Canadian weekly magazine MacLean’s sent reporter June Callwood to Stephenville, Newfoundland to report on the progress of the “Mid-Atlantic Gas Station” which, following the Avro Arrow disaster, was now the biggest positive aviation story in Canada. Her eight-page feature article drew plenty of attention and a nervous reaction from many Newfoundlander politicians who were worried that aircraft would now be bypassing the traditional fuel watering hole at Gander. They needn’t have worried. Image via internet

The star of June Callwood’s feature story in MacLean’s was former Afrika Corps combat barber Gustav “Gus” Gazzler, one of a select group of Supertest employees who were chosen to train to become air-to-air refuelling boom operators, or “boomers”. Gazzler is seen here giving the windscreen of his boom operator cab a shine at Harmon AFB. “Ya… old habits die hard,” quipped the former service station pump jockey. “I offered to check the oil and tire pressures, but the crew chief declined.” Photo: USAF

During June Callwood’s flight aboard Supertest’s Superstratotanker Pepe Lemieux, she photographed German-Canadian Gustav “Gus” Gazzler, one of a new breed of civilian KC-97 boom operators or “boomers” being trained by American military instructors for the upcoming transoceanic fuel service. Here, Gazzler deftly edges the refuelling probe towards a USAF Lockheed Constellation over Prince Edward Island during a three-hour refuelling training flight from Harmon AFB. Gazzler, a former German POW, was selected from over 300 applications from Supertest employees and station managers across the country. Over the noise and buffeting of the refuelling cab, Callwood reported that he said, “Well, at least I don’t have to ask them if they want regular or high test, and I can’t very well clean their windshields!” In addition, MacLean’s sent a photographer to cover the refuelling training from the receiving end. Photo: USAF

Standing in the astrodome bubble of a USAF Lockheed Constellation, photographer Cannon shot this image of Gazzler’s “poke.” 12,000 feet below, the seas looked a little rough and Callwood shuddered to think what would happen if something went wrong or the airliners failed to find the flying gas station. Photo: USAF

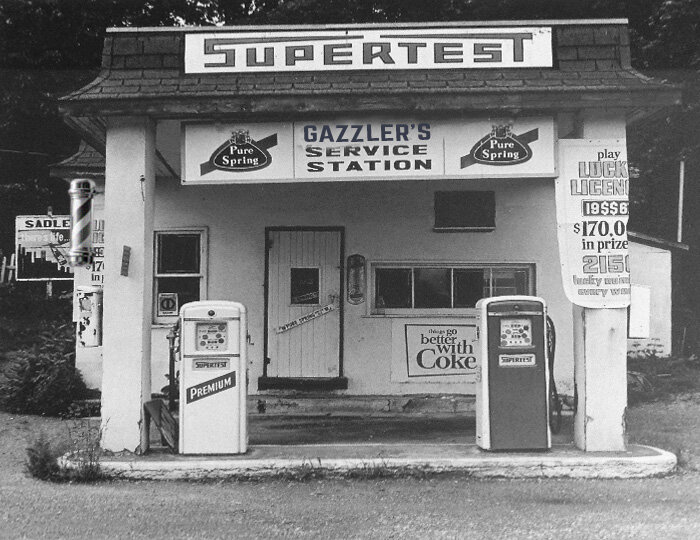

Gus Gazzler was interviewed by the author in 1997 at the age of 79. At the time, he was living in a senior’s containment facility in Thunder Bay, Ontario. His health was in jeopardy with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which he attributed to a life of breathing petrochemicals and smoking Chesterfields. “I was a Supertest man, through and through. I owed a lot to Canada and working for ‘Canada’s All-Canadian Company’ under the orange maple leaf was a great honour for me.” Gazzler had been a German Prisoner of War, held in the infamous POW camp at Red Rock, near Port Arthur, Ontario (now Thunder Bay). Gazzler had been a combat barber with the Afrika Corps and had been General Erwin Rommel’s personal hair stylist. “The general liked it high and tight, with just a touch of pomade on top.” said Gazzler back in 1997. He was captured at the First Battle of El Alamein along with a 40 gallon drum of Ludendorf’s Feinste Haar Pomade. Gazzler was sent to Canada, the pomade was sent to Field Marshal Claude Auchinleck, commander of the Allied forces. Following his release in 1945, Gazzler returned to his destroyed home in Dresden, but longed for the peace and quiet and rugged beauty of the Lakehead region. He returned to Canada a year later and worked as a barber in Port Arthur until he had saved enough money to buy a small Supertest Service Station. “After that, I never charged for a haircut again,” said Gazzler, “But I would give anyone who wished, a free hair cut with any fill-up. I only did one style though—‘The Rommel.’ If people didn't like it, tough.” Photo: Shutterstock

Gazzler’s Supertest Service Station in Port Arthur, now a protected national historic site. Note the barber pole at left. Photo by John Flanders via Gustav Gazzler Collection

By mid-summer of 1960, the crews were regularly “poking and tanking” USAF and USN Constellations and felt ready to demonstrate the concept with media and airline executives out over the ocean. Supertest sent out invitations to media, partners, dignitaries and airline executives to join in an in-flight demonstration halfway across the Atlantic. A USAF Constellation was to pick one group up at Idlewild Airport on Long Island and fly them out over the Ocean for a rendezvous with the KC-97s, while another Connie would leave from Prestwick in Scotland with European dignitaries. The idea was for the Constellations to refuel from one of the tankers and fly on to the opposite side of the ocean for a press conference. It was planned that at one point the two linked pairs of aircraft were to pass within 1,000 feet of each other for a photo op (a USN Lockheed Neptune was accompanying the KC-97s and would have media aboard).

There was a problem however. With the Constellations already en route, the crew of KC-97 Pepe Lemieux reported hydraulic problems with their boom. Pressure could not be maintained and the boom could not be reliably deployed. The teams scrambled to find an answer and suggested that James Keeton refuel both aircraft. But that left zero leeway in case of another technical problem. If they could not refuel both aircraft, one or both of them might not have the fuel to make it safely across.

Radio signals recalled the Constellations in time, but the demonstration was scrubbed for safety reasons. Bayer & Zeller apologized to a long list of dignitaries, but the damage was done. In trying to reschedule another demonstration a week later, only a quarter of the invitees responded yes, and none of these were airline executives. The airlines had, over the intervening year since the beginning of the MAARP experiment, seen clearly that jets were the way to the future. Writers of popular culture took to calling the glamorous and wealthy air travellers the “Jet Set” and one airline industry writer from the Wall Street Journal called those traveling on propliners the “Yet Set”, as in “Are we there YET?”

Every airline executive who had previously pushed Supertest to attempt the MAARP project was now distancing himself from the project, citing costs and delays, but everyone now understood that transatlantic propliner service was going the way of the transatlantic passenger ship—to the history books.

An emergency meeting of the Supertest Board of Directors was called and after a short discussion it was unanimous—MAARP had blown the only opportunity they had. Truth be told, even if the refuelling photo-op had been a success, the industry was in a new mindset—powered by jet engines. They instructed Supertest management to shut down the project, pay off crews and strip the Supertest brand and titles from the two KC-97s before flying them back to Seattle.

Supertest tried hard to keep the failure as low key as possible, and Canadians obliged… likely out of embarrassment. The project simply disappeared and crews returned to their previous lives. Supertest attempted to destroy all of its photographic records and few images survive today.

The last word went to Gus Gazzler, who said “Ya, it hurt me more than losing the war, but it was a happy memory anyway, like the good times I spent with Rommel. He’s dead, the tankers are dead… but I am alive and living in the best country in the world. Nein… there’s no problem for me.”

A photograph from one of the last tests of the Supertest Mid-Atlantic project showing another USAF Constellation refuelling from Superstratotanker James Keeton off the coast of Newfoundland. Not long afterward, Supertest pulled to plug on the entire idea, claiming lack of commitment (read interest) from airlines and the now obvious unstoppable paradigm shift to all-jet operations. While it would take more than a decade to fully clear the skies of piston-pounding propliners, the writing was on the wall. Or perhaps it was skywriting in the form of the jet vapour trail captured in this photo… heading across the sea at 35,000 feet and over 500 mph. Photo: USAF

A sad shot of KC-97 Pepe Lemieux in storage in the fall of 1960. Her last flight with Supertest would be her ferry flight back to Seattle in October 1960. Photo: Harmon Historical Society

Postscript

Today, the concept of a civilian run air-to-air refuelling service is not as farfetched as it seems. Virginia-based Omega Aerial refuelling services has now done over 5,000 missions and delivered 180,000,000 lbs of fuel in 49,000 separate “plugs”. Their website claims “Since 2000, Omega Aerial Refueling Services, Inc (OARS) had been the leader in commercial in-flight refuelling services completing more missions and delivering more fuel than any other carrier in the world.” The take-away here is that there are others. Not so farfetched after all Uncle James. Photo: Wikipedia

Researching the web, the author found this 1/72nd decal sheet for KC-97 Stratotanker models featuring Supertest decals along with other Stratotanker markings.