BODY ENGLISH — The Science and the Art of the LSO

You are standing at the very edge of a steel cliff, high above the Indian Ocean. You look backwards across a hot steel deck shimmering in the 100ºF heat to the vast expanse of pale white-blue ocean. A white churning wake recedes in an arrow straight line, like pale smoke, until it disappears into the steamy haze that hides the line where the warm ocean meets the heat washed sky. A long, quiet ocean swell steadfastly raises and drops you 15 feet through a twenty second period. The soles of your feet burn through your tennis shoes. You do not have the benefit of a wind screen, so you lean backwards against the hot 35-knot wind pushing down the flight deck. Your feet are set far apart to steady your movement and your heart. Behind you, below you and in fact as part of you, lives one of the greatest and most storied aircraft carriers of the Royal Navy—29,000 tons, 1,900 men, 60 fighters and bombers, 750 feet long, nearly 100 feet wide.

120,000 steam driven horsepower hum up from six decks below, firmly vibrating the deck beneath your feet. You feel the rhythmic thrashing of the ship’s screws, the steady pulse forward, the rise and the fall, the push at your back, the sweat in your hands as you grip the two Bakelite handles of your signalling lamps, the heat of the harness you wear with a third lamp strapped to your chest. You smell the acrid, black scent of diesel, your own unwashed clothes, the hot smell of sun-blasted paint and cable grease. You hear the winding down sound of the landing aircraft’s radial engine approaching, the snap of signal flags, the passage of water hissing down the hull 60 feet below you, the twang and crash of the crash barrier going back up behind you. You taste the salty air, the dry bite of stress, the grit of an aircraft carrier in the peak of performance.

You feel the eyes of a hundred men on your back—staring from the catwalks, the flight deck, the goofers* galleries and the bridges—watching, waiting, anxious, half blinded by the brilliance of an equatorial sun. You are the pivot point of a great endeavour, the saviour of 50 weary pilots, the last chance to get home to live another day. A pilot, a squadron, a ship, a battle and a war rest on your shoulders. This day you will never, ever forget. You are a Deck Landing Control Officer (DLCO) of the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm but everyone on board calls you “Bats”, short for batsman. Above all though, you feel the eyes of a single scared, tired Corsair pilot staring at you and your outstretched arms from a mile away, connected in trust.

In the 1950s, James Michener wrote The Bridges at Toko-Ri, a powerful and gripping novel about carrier operations during the Korean War. In preparation for this, he lived on-board a United States Navy fleet carrier for months. It was here that he got to understand the greatness of the naval aviator and in particular the Landing Signal Officer (LSO—the American equivalent of the DLCO). No one has ever expressed the finality of the LSO’s decisions better than Michener:

“There always came that exquisite moment of human judgment when one man—a man standing alone on the remotest corner of the ship, lashed by foul wind and storm—had to decide that the jet roaring down upon him could make it. This solitary man had to judge the speed and height and the pitching of the deck and the wallowing of the sea and the oddities of this particular pilot and those additional imponderables that no man can explain. Then, at the last screaming second, he had to make his decision and flash it to the pilot. He had only two choices. He could land the plane and risk the life of the pilot and the plane and the ship if he had judged wrong. Or he could wave-off and delay his decision until next time around. But he could defer his job to no one. It was his, and if he did judge wrong, carnage on the carrier deck could be fearful.” —James Michener, The Bridges at Toko-Ri (1953)

In the world of aviation, the training and singular purpose of the military aviator is an expression of competency at its finest. Among military aviators, the fighter pilot is the one thought to have the chops, the quick reflexes and the ability to make fast decisions on the fly in a life or death situation. Of the fighter pilots, those required to land on a short length of a moving flight deck in all kinds of weather, day or night, are considered to be the crème-de-la-crème of the breed. Of those carrier-qualified fighter aircraft pilots, there is a small percentage who will make it to the very, very pointy end of the spear. In the Royal Navy during the Second World War, these select naval pilots were called Deck Landing Control Officers (DLCO or Bats). In the United States Navy, they are known today as Landing Signal Officers (LSOs or Paddles).

These highly experienced aviators are trained to help other pilots in landing on an aircraft carrier. Their job is to bring home, or to “recover”, the aircraft of the carrier wing, despite the weather condition, during daytime or in the black of night or in heavy seas. Ever since pilots began landing on aircraft carriers, the ones with the greatest knowledge of the techniques, risks and limitations of deck landing have been called upon to assist their brother and sister aviators. They are required to stand at the rear of the flight deck, exposed to the weather and dangers, facing the landing aircraft, and judge that pilot’s glide slope, airspeed, attitude and lineup and transmit to him corrective orders to ensure a safe recovery.

Author Tommy H. Thomason, in Waving them Aboard, wrote:

“For some reason, the Royal and US Navies developed slightly different techniques for landing aboard. Royal Navy pilots were taught a descending approach and the LSO signal for the pilot being above the correct approach path was lowered paddles, meaning descend. The U.S. pilot made a low, flat approach and the LSO signal for being too high was raised paddles. (The signals for lineup were the same since the US Navy signals for correcting height and lineup were inconsistent, like tilting down to the pilot’s left to ask for tightening the turn and raising the paddles up for descend.) Fortunately, there was very little cross-decking between the services during the war.

In 1948, the Royal Navy elected to change to the US Navy LSO signals and shortly after that, adopted the low, flat approach as well. A reduction in accident rate resulted although it’s not clear why. The British subsequently developed the mirror landing approach aid. The mechanics of the mirror concept combined the original British descending approach and the American signal for being too high, with the ball on the mirror going up when the airplane was above the desired ‘glide’ slope.

Following the transition to the mirror-guided approach, the LSO role was initially downgraded to more of an administrative one in the belief that the pilot no longer needed his guidance. It was soon established that the LSO could detect a trend quicker than the pilot and moreover, had a better sense of deck motion, which affected the validity of the mirror display even though it was gyro stabilized. As a result, the LSO was again established as the controlling authority for the approach.”

War memoirist Norman Hanson (Carrier Pilot) wrote this powerful and simple passage about being brought aboard HMS Illustrious for the very first time by the legendary DLCO Johnny Hastings, himself a highly experienced fighter pilot aboard Indomitable, Avenger and Biter :

“Now we were flying downwind, locking safety harness, locking open the hood, increasing pitch, lowering flaps; first to ten degrees, then to 20. Now I was abeam of the stern of the ship. Turn 180 degrees to port; full flaps. Already Johnny [Hastings] was signalling for me—‘Roger’ as you go. A shade faster—OK. Now come down, down, DOWN, damn you! CUT! I chopped back the throttle, held the stick steady as a rock. Three seconds, then I was on the wire. My body lunged forward against the harness with the deceleration—I was down. A red-capped director of the flight deck party waved me back with both hands. I released the brakes to allow the wind to blow me back a few feet, so that the arrestor wire could be disengaged. Up hook, up flaps and taxi forward over the crash barriers. I jumped to the deck—three and a half inches of armour plating.

The air was loud with tannoy noise. Up there on my left, as I walked down the flight deck, was the great island; and the whole ship, alive with men in a variety of rigs, fairly hummed with activity.

It was one of the greatest moments of my life.

Despite the differences in signals and nomenclature, the LSO and the DLCO were much the same—the best pilots doing the most difficult job on the carrier. One thing however did seem to stick out when viewing the hundreds of photos of “Paddles” and “Bats” posted on the internet, and that is that the Royal Navy batsman seemed to do his task with a little more flourish, more zippidy-doo-dah and more body English than his American counterpart. Here for your enjoyment is a non-definitive, probably incorrect in spots, photo essay of the life, times and indeed styles of the Carrier Group’s pivot point—the Landing Signal Officer.

* A goofer is a sailor or airman spending time in the catwalks or the galleries at the aft of the island, watching for the pure enjoyment of the spectacle. The 5 September 1946 issue of Flight Magazine had a story on the Goofers. The writer who went by the name of Pyfo explained: “At the after end of the island superstructure of our large fleet carriers of the Illustrious class there was a clear bit of deck where, by some oversight, My Lords have omitted to put some gun or other warlike implement. This is known as the ‘Goofer’s Platform’ or the ‘Goofers’. A Goofer in Naval slang—or anyone’s slang for that matter—is a person who stands gazing at some incident in which he is not actively concerned. This platform was where we—for all Naval Air Arm types are goofers—gathered to watch other poor characters landing.”

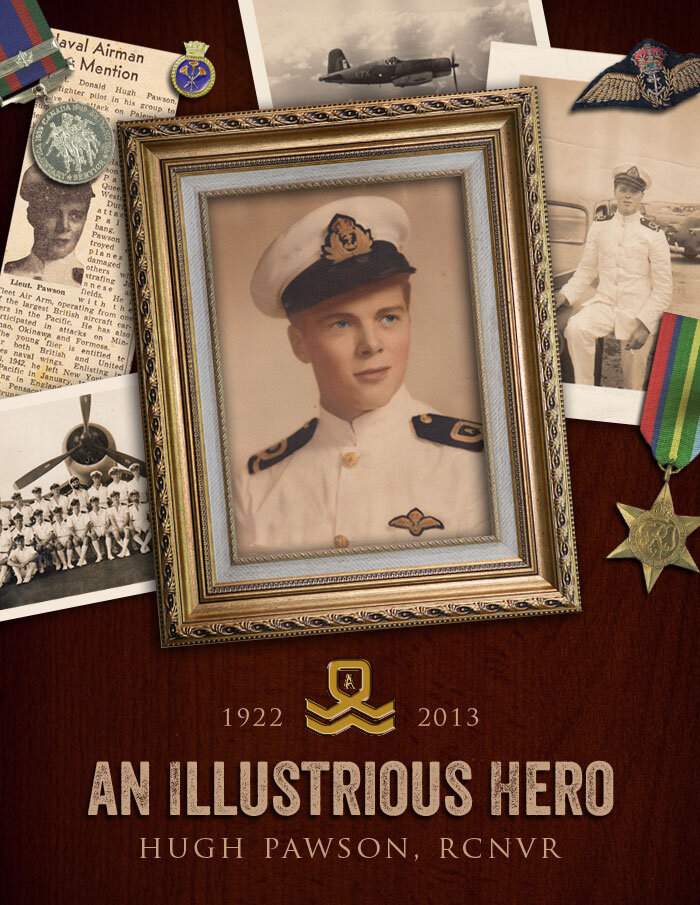

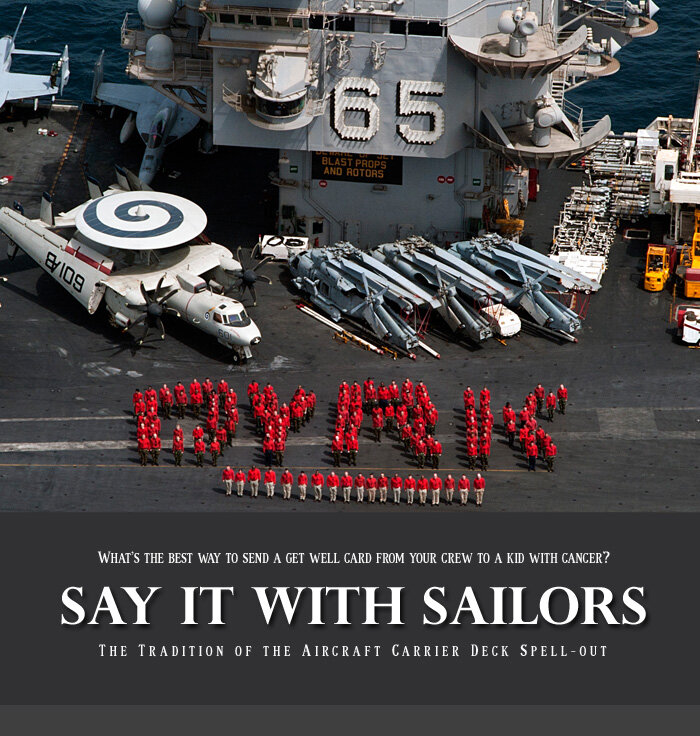

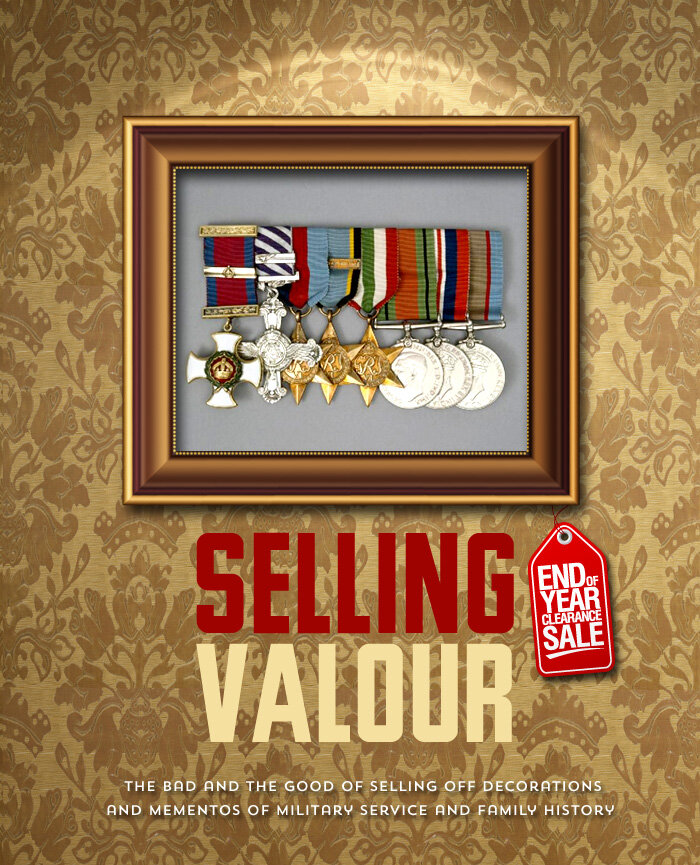

Related Stories

Click on image

From the very beginning, danger stalked the carrier landing.

While Eugene Ely was credited with the first takeoff from and landing on a ship—the modified deck of the USS Birmingham, it would be a Royal Naval Air Service officer, Edwin Dunning, who would make the first landing on a ship underway. In the case of Ely, he was nearly killed when, on his first takeoff from Birmingham on 14 November 1910, his aircraft touched the water before climbing away. Dunning was not so lucky. After successfully landing on HMS Furious in August 1917, he was killed five days later trying to repeat his feat, despite the attempts of a dozen fellow officers trying to catch him before he went over the side.

The danger has never gone away, but the professionalism of deck crews and the experience of LSOs have gone a long way to reducing the injury, damage and death which has stalked the carrier since its inception.

Squadron Commander Edwin Harris Dunning, DSC of the British Royal Naval Air Service, was the first pilot to land an aircraft on a moving ship. He did so by landing his Sopwith Pup on the specially equipped battle cruiser HMS Furious in Scapa Flow, Orkney on 2 August 1917. He actually hovered his aircraft while attending sailors rushed to grab hold of him as there was no arresting gear. Here he is being congratulated by the men of Furious who helped him come to a stop on 2 August 1917. He was killed five days later, during his second landing attempt of the day, when an updraft caught his port wing, throwing his plane overboard. Knocked unconscious, he drowned in the cockpit. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Royal Navy Air Service sailors and officers race to restrain Edward Dunning’s Sopwith Pup on the forward flight deck of HMS Furious, 5 days after his first successful landing on a moving ship. A second later a crosswind gust caught his left wing and he veered to starboard. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Unable to stop Dunning, officers and sailors of the Royal Navy Air Service can only watch as Dunning’s Pup veers to starboard and over the edge. Dunning was knocked unconscious and drowned. He was the first pilot to successfully recover to a ship in motion and the first to die attempting to do it. Sadly there would be many, many more in this unquestionably dangerous activity. Photo: Imperial War Museum

An early Landing Signal Officer(LSO) stands at the edge of the ramp of the flight deck of USS Langley (CV-1) using ordinary signal flags, while a Vought VE-7F Bluebird makes its final approach. According to Navy legend, the first LSO was Commander Ken Whiting, the XO of Langley. Legend has it that he observed and coached many of the first landings from the position at the port stern of the aircraft that would become the LSO position we know today and grabbed two white sailor’s hats to make his approach coaching corrections more visible. Standardized signals and the use flags, and eventually paddles, followed in short order. In normal flying operations, an aircraft carrier should be steaming into the wind to maximize headwind over the deck, allowing aircraft to maintain a lower ground speed. The fact that the Langley, America’s first aircraft carrier, is tied to a pier is strange. The Bluebird pursuit aircraft was a slow-moving biplane landing with a slow landing speed, but one does not often see a landing on a stationary carrier. Note the large net on whisker poles at the stern of the ship. Not sure whether this is to catch an aircraft that rolls back after a ramp strike or if it is to prevent damage to the ship in the event that an aircraft crashes into the stern. US Navy Photo

An early image of a US Navy Landing Signals Officer, on board the aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV-2) in 1931, using flags to guide an Loening OL-8 amphibian to a recovery on board the ship. As flags, in the wind over the deck, would be driven flat, therefore less visible, it was soon decided to go to a stiff paddle or louvered bat. The two-place Loening was returning from relief mission to Managua, Nicaragua, following a devastating earthquake there on 31 March 1931. It had a magnitude of 6.0, and killed 2,000 people. The LSO uses traditional semaphore signal flags and stands on a scaffold next to, instead of on, the flight deck itself. A plane guard ship can be seen in the distance should any aircraft be forced to ditch or come to grief during a landing attempt. US Navy Photo

This batsman from HMS Ravager, the Rudolf Nureyev of batsmen, is the most expressive of all as he lunges toward a landing Fleet Air Arm Fairey Barracuda like a joyful gazelle, welcoming the aircraft aboard. HMS Ravager (D70) was an Ruler class escort carrier built on the West Coast of the United States and operated by the Royal Navy during the Second World War. Ravager initially served as a convoy escort in the Atlantic theatre. Later in the war she was used mainly as a deck-landing training carrier and this photo is likely from that time as a training ship. In February 1946 she was returned to the US Navy and the hull sold for civilian use in July 1947 as a freighter, being renamed the SS Robin Trent. All 28 Ruler class escort carriers were built by the Seattle-Tacoma Shipbuilding Corporation and supplied under Lend-Lease. They were the most numerous single class of aircraft carriers in service with the Royal Navy. Some names of these carriers were from an interesting list of job descriptions: Patroller, Puncher, Reaper, Searcher, Slinger, Smiter, Speaker, Tracker, Trouncer, and Trumpeter, while other names for the class were derived from the titles of the Royal/Ruling Class or heads of state around the world: Arbiter, Ameer, Atheling, Begum, Emperor, Empress, Khedive, Nabob, Premier, Queen, Rajah, Ranee, Ruler, Shah and Thane. Royal Navy Photo

A Deck Landing Control Officer aboard HMS Illustrious enthusiastically guides an 806 Naval Air Squadron Grumman Martlet (Wildcat) pilot home in wet weather en route to Malta, using the hand-held lighting system. On a grey day like this, the lights would have been a very effective system. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Carrier aircraft are required to take off and operate under poor weather conditions as well as fine, so are Deck Landing Control Officers of the Royal Navy. Here we see the same Deck Landing Control Officer from HMS Illustrious as in the previous photo, using the reflector light system to send clear messages to an oncoming aircraft in inclement weather. One wonders if this is Johnny Hastings, the legendary batsman of Illustrious spoken of frequently with such reverence in the war memoir Carrier Pilot by Corsair pilot Norman “Hans” Hanson of the Fleet Air Arm. Also, there was an Aircraft Handling Instructor by the name of Alec Simpson, who was also one of Illustrious’ batsmen. Simpson’s son Alec works with Transport Canada here in Ottawa. If anyone knows who this DLCO is, let us know. Royal Navy photo

Dry Land Training—teaching the art of Deck Landing Control

Before a Fleet Air Arm pilot or a Deck Landing Control Officer can think about taking his skills to the carrier, he or she must learn on dry land on airfield where a dummy deck is painted on the runway. The Airfield Dummy Deck Landing was an essential part of the training of a carrier pilot and a Deck Landing Control Officer/LSO.

A Deck Landing Control Officer “bats down” a Fairey Barracuda on a Dummy Deck Landing Airfield on the Isle of Man during the Second World War. Note that the arresting wires are simply painted on this dummy deck. Images via www.island-images.co.uk

An instructor demonstrates a “cut” for young Deck Landing Control Officers from HMS Implacable at a training field in the United Kingdom as a Hawker Sea Fury flashes past. Photo via naval-history.net and Lieutenant Commander James Henry Summerlea

A rather long-haired “Old Professor” William “Flashman” Hawley, with his normally pomaded locks in disarray, demonstrates the use of louvered cloth paddles to bat in an approaching fighter at a Deck Landing Control Officer training school on land. HMS Implacable pilot and batsman trainee Jock Hamilton looks on, smoking a cigarette. Photo via naval-history.net and Lieutenant Commander James Henry Summerlea

Deck Landing Control Officer Instructor Bill Hawley watches over a charge as he works a Navy fighter to the ground at a training field. Photo via naval-history.net and Lieutenant Commander James Henry Summerlea

Back on HMS Implacable, Bill Hawley (looking less like a long-haired maestro) and Johnny (Curly) Blunden watch as fighters overfly HMS Implacable. Photo via naval-history.net and Lieutenant Commander James Henry Summerlea

At a training school in England, both the Deck Landing Control Officer and the pilot of the Fairey Albacore learn their respective arts at the same time. Here we can just make out puffs of smoke as the Albacore, with landing flaps down, touches down with the batsman showing the cut signal. It is evident that the port wing of the torpedo bomber will roll over the head of the batsman as it rips down the runway. It is likely this is a touch and go as there are no arresting cables on this practice field. Royal Navy Photo

An image of a rather lackadaisical US Navy Landing Signal Officer guiding a Douglas SBD Dauntless on a shore base during the Second World War with a signal I can’t quite make out. US Navy photo

Compared to the previous photo, this North American Fury looks properly lined up and not in danger of striking this LSO during Field Carrier Landing Practice (FCLP) in 1954. US Navy Photo

“Bats” and the Boys. The Deck Landing Control Officer of HMS Ravager stands in front of his fellow deck crew in the air department, with his own team in light coloured vests. At the back front left to right we see the flight deck tractor, aircraft starter trolley, aircraft handlers with their chocks (centre), then more aircraft handlers with manual tow bars, then crash and fire crew. Photo from royalnavyresearcharchive.org.uk

Out on the Indian Ocean, this HMS Illustrious batsman wears tennis shoes and Bermuda shorts to help him deal with the heat, though he is one of the lucky ones standing in the cooling effect of the 30-knot air blowing down the deck. He wears a light contraption that helps the oncoming pilot see the signals from much farther out. This consists of a reflector with bulb in each hand and a central one strapped to his chest. From a distance, the pilot would read the relation between the hand-held lights and the central light to understand what he needed to do. In this case he is being told he is too low and needs to climb to keep in the correct angle. All he had to do was mimic the position of the hand-held lights with his aircraft—easier said than done. One wonders who he is signalling to—could it be our own Hugh Pawson? Photo: Imperial war Museum

The same Illustrious batsman in the Indian Ocean. He seems to be putting everything into it, including his tongue. One wonders what this fellow would do if he had to make a fast dash to his right to avoid an oncoming and off line Corsair. Tethered as he is, one suspects he wouldn’t get too far. The difference between American and British LSOs was the nature of their signals. Generally, US Navy signals were advisory, indicating whether the plane was on glide slope, too high, too low, etc. Royal Navy signals were usually mandatory, ordering the pilot to add power, come port, etc. When “cross-decking” with one another (i.e. landing on each other’s carriers), the two navies had to decide whether to use the U.S. or British system. Photo: Imperial War Museum

A Royal Navy batsman lunges as he brings in a Fairey Barracuda of 831 Squadron, Fleet Air Arm on board HMS Furious. The carrier Furious was one of the first carriers of the Royal Navy, which began her life as a modified battle cruiser in the First World War with a flight deck forward of the bridge. Royal Navy Photo

Batsman Lieutenant Malcolm Brown, his name painted in white on the back of his Irwin flying jacket, warmly bundled up against the cold North Atlantic with flight boots, works a Supermarine Seafire down to the deck of HMS Indomitable. He wears his name emblazoned on his back. All I can read for sure is the last name: Brown. Royal Navy photo

A batsman on HMS Formidable gives the signal to an approaching 820 Squadron Fairey Albacore pilot to get lower as he passes over the round down. Photo via Imperial War Museum

The same Royal Navy batsman from HMS Formidable as in the previous photo gives the “cut” signal to possibly the same Fairey Albacore from 820 Squadron. Royal Navy photo

Another Royal Navy batsman encourages a Firefly pilot with a little body English. Royal Navy Photo

Lieutenant Commander Donald Macqueen, RNVR, Fleet Air Arm pilot and the greatest batsman of all time. According to the British newspaper, The Telegraph, Macqueen “batted in” more than 66,000 aircraft landings on fleet carriers and Airfield Dummy Deck Landings (ADDL) on practice fields in the United States and England—more than any other Royal Navy Deck Landing Control Officer (DLCO) in history. The London Times has different numbers for Macqueen—20,000+ carrier landings and 200,000 ADDLs. His record was an astonishing 775 landings in a day! Macqueen flew Swordfish torpedo bombers with 823 and 810 Naval Air Squadrons from the carriers Glorious, Illustrious, Ocean, Vengeance and Theseus. He died in 2010. Photo via the London Times

The pilot-batsman connection from the pilot’s viewpoint. With his aircraft’s nose held high, a pilot of a Fairey Swordfish watches the Royal Navy batsman (centre-right) signal that his wings are level and on line with about 50 yards to go before trapping. Royal Navy photo

Only a few feet above the flight deck, a Deck Landing Control Officer gives the pilot of a Fairey Swordfish the “cut” signal, telling him to chop power to his engine. In the Royal Navy, instant obedience to this signal was essential for a successful trap of the landing Swordfish. One of the arresting cables (cross-deck pendants) can be seen on the deck in the foreground lying over a retractable device that elevates the cable a few inches above the deck. Royal Navy photo

Another pilot’s eye view of a batsman, this time from a Canadian pilot coming in to land on HMCS Magnificent. One wonders if this is Lieutenant Barry Hayter, the No.1 Deck Landing Control Officer aboard the Maggie. Photo via Bill Ewing, RCN, RCAF

A Griffon-powered Supermarine Seafire Mk 47 is batted in by the Deck Landing Control Officer aboard HMS Triumph. Note the other deck crewman watching from the safety of the catwalk. We can see the under-wing and centre-line additional fuel tanks, which were found on the Mk 47. The batsman would, if required, dive headlong into “the nets” to avoid an off line aircraft, but it was not uncommon for a batsman to miss it entirely and end up falling 40 to 60 feet to the ocean below. HMS Triumph, a Colossus-class fleet carrier, was the ninth of ten ships of the line to carry the name—the first was as a 68-gun galleon built in 1561, the last was a nuclear-powered Trafalgar-class fleet submarine launched in 1990 and currently in service. Royal Navy photo

Using the body-worn electric light system, a batsman signals to a Grumman Martlet of 881 Squadron coming in to land on HMS Illustrious during operations in the Indian Ocean during the Second World War. 881 Squadron was destined for HMS Ark Royal, but when the ship was sunk on 13 November 1941 the squadron was allocated to HMS Illustrious, sailing for the Indian Ocean in March 1942. In May 1942, the squadron, joining 882 squadron, supported the capture of Diego Suarez in Madagascar, jointly shooting down 7 enemy aircraft. In the middle of the month 882 was absorbed into 881, and the squadron returned to the UK in 1943. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The Dangerous life of the Landing Signals Officer

US Navy landing signal officers scramble to safety shortly before the ramp strike of a Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat aboard an aircraft carrier. US Navy photo

A Vought F4U-4 Corsair of Marine Attack Squadron VMA-322 about to slam into the ocean in 1949 after a botched landing attempt on the U.S. escort carrier USS Sicily (CVE-118). Landing Signal Officer (with the paddles) and his assistant (with the notepad) running to the opposite side of the flight deck to escape decapitation. If this LSO was wired with the same electric lamp system that the Illustrious batsman had earlier, he would not have been able to scramble for his life. Photo: US Navy Naval Aviation News

This LSO has the biggest balls in the Navy for standing his ground and not leaping to the nets as this US Navy Bombing Squadron 8 (VB-8) Douglas SBD Dauntless drops to the deck just a few feet from his head. The Dauntless and VB-8 are part of the air group attached to Captain Marc Mitscher’s legendary USS Hornet (CV-8), during the Battle of Midway. In the distance we see plane guard destroyers keeping pace. US Navy Photo

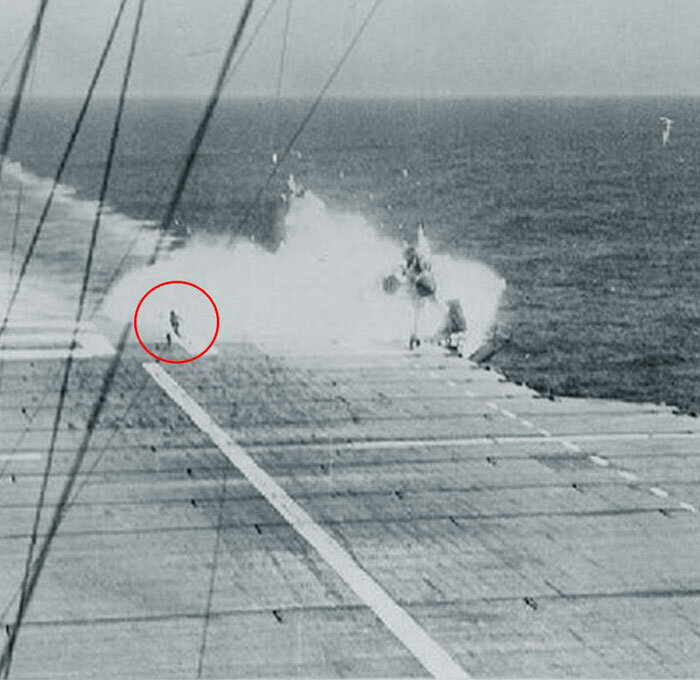

Lieutenant Commander Jay Alkire, USNR, of the VF-124 “Stingrays”, Carrier Air Group Twelve (CVG-12), aboard the USS Hancock (CVA-19) is far too low as he reaches the round down. In this photo, we see him pitch his F7U-3 Cutlass up drastically in a last minute attempt to avoid striking the stern of the ship. Note the LSO running for his life.

In a very powerful photograph of the same event as the previous shot, but from another angle, we see Ted Reilly, a US Navy Landing Signal Officer running for his life just prior to a Vought F7U-3 Cutlass impacting the edge of the flight deck of the aircraft carrier USS Hancock (CVA-19) on 14 July 1955. The belly of the Cutlass reflects the white churning wake of the carrier. Sadly, the Cutlass’ performance suffered due to a lack of sufficient engine thrust, (earning it the sad nickname of Gutless Cutlass); consequently, its carrier landing and takeoff performance was notoriously poor. Pilot, Jay Alkire, had no chance at this point to avoid his death. US Navy Photo

LSO Ted Reilly saves his life as Alkire’s Cutlass strikes the deck of Hancock and disintegrates, spraying flaming jet fuel over the deck and catwalk. US Navy Photo

The terrible result of LCDR Jay Alkire’s ramp strike on landing aboard USS Hancock during carrier qualifications off of the California coast. The disintegrating airframe spins off the port edge of the flight deck. Alkire was killed, still strapped into his ejection seat, when the wreckage of the Cutlass’ airframe sank. Also killed by burning fuel were two boatswain’s mates and a photographer’s mate on the port catwalk (one wonders if one of the previous photos was taken by the photographer’s mate that died). Thankfully, LSO Reilly survived. US Navy Photo

The United States Navy Landing Signal Officer

There is no doubt that the American LSO is the best in the world today and was among the finest of the Second World War. Though some American practitioners, like the famous Dick Tripp, could be said to be not only uber-competent, but uber-stylish as well, the bulk of the official and unofficial photographic evidence of the LSO and DLCO in action during the war shows us that the British DLCO took his job with an extra twist of lemon, a cinnamon stick, chocolate swirls and a shot of whipping cream, while the American LSO did his job like a cup of straight black coffee—tough, honest and without sweetening.

Of course, style doesn’t matter one whit when it comes to the safe landing of a powerful, dangerous-to-fly fighter aircraft onto a small, moving piece of steel 60 feet above the water. It’s simply an observation I have made from the hundreds of photos I have seen that, while a job may be serious and important and possibly critical to the war effort, it can still be executed with panache and some body English. There are traffic cops and then there are the traffic cops that end up on YouTube with dance-like moves and energetic whistles. Here’s to the British DLCO and their freestyle approach to a demanding art form.

But, it was an American who, according to legend, created the idea of the Landing Signal Officer. From the website of Carrier Landing Consultants, we find a brief history of the LSO, starting at the beginning:

“Landing Signal Officers (LSOs) have had a key role in US Naval Aviation since its earliest days. The very first LSO was reported to be a pilot who waved two sailor’s caps in the air to tell an incoming pilot it was unsafe to land.

The first executive officer of a US Navy aircraft carrier (CDR Kenneth Whiting aboard the USS Langley) watched pilots’ landings with an eye toward improving them, recording individual landings with a hand cranked motion picture camera—the ancestor of today’s in-deck PLAT cameras. Observing landings from the port aft corner of the flight deck, he would often give helpful suggestions through body language of what the pilot on approach should do to effect a safe landing. This worked so well the position was institutionalized as the ‘Landing Signal Officer’ or LSO.

The first LSOs communicated to pilots via hand signals, amplified with large colored flags, or wands. Since these wands were roughly the same shape as large ping-pong paddles, the nickname ‘paddles’ has stuck with LSOs ever since. Despite the retirement of actual hand-held paddles in the early 1960s, the act of controlling an aircraft landing on an aircraft carrier is still referred to as ‘waving’.

Other countries had carriers and LSOs as well. The UK called theirs ‘batsmen’. While the United States was the first to fly an aircraft off and onto a ship (Eugene Ely, 1910 and 1911), the Royal Navy had the first functional aircraft carrier, and was responsible for many of the great advancements in mid-20th century carrier technology, including the angled deck, mirror landing aid, and armoured flight decks. Today, France, Russia, Brazil and Argentina practice arrested landings aboard modern aircraft carriers. Other countries like India and the UK are building carriers with arrested landing capability as well.

Light signals and radios have replaced the hand signals of the early 20th century, but the goal of waving is the same as it was in World War II: get an aircraft safely aboard on center line, the first time, no matter the weather or time of day.”—from Carrier Landing Consultants

Here’s to the American LSO—professional, experienced, trusted and the finest in the world... just not the fanciest.

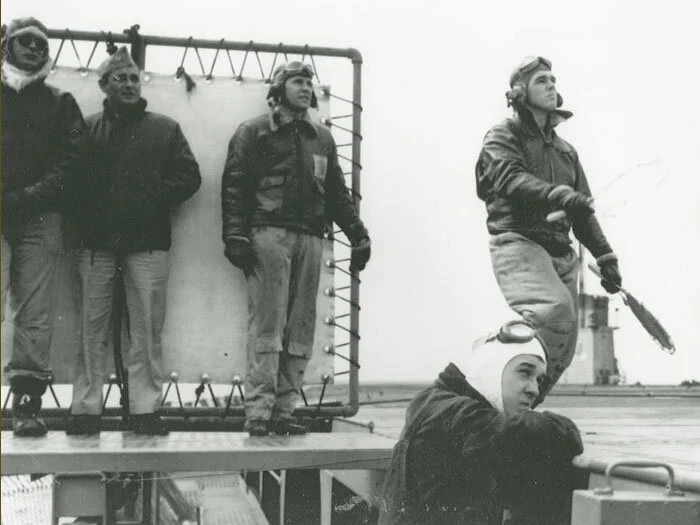

Landing Signal Officer Ensign R.J. Grant, aboard USS Enterprise in March of 1945, goes to work sheltered from the wind over the deck by a screen, joined by other pilots who watch the landings and gain experience. When an aircraft carrier launches or recovers its aircraft it turns into the wind and increases to full speed to give as much wind over the deck as possible. In some conditions, the wind whipping down the deck might be in excess of 40 knots. Such wind speeds buffeting the LSO would almost knock him off his feet if it were not for the screens they could stand behind. US Navy photo

A Douglas TBD-1 Devastator is brought in by a rather stiff LSO aboard USS Enterprise in July 1941. While I know that American LSOs are the finest anywhere and, in fact, can be considered the creators and the greatest practitioners of the art form, the style of the average Second World War LSO of the US Navy pales in comparison to the flourish, virtuosity and panache of the deck dance put on by the Royal Navy Deck Landing Control Officer. US Navy Photo

The Perfect Cut. A US Navy Landing Signal Officer giving a “cut” signal to a Grumman TBF Avenger during the Second World War. Cutting the power at this point, the heavy torpedo bomber will drop like a stone and catch a wire. Note the less than theatrical signal from the LSO. Like traffic cops, there are those that get the job done and then there are those that make an art form out of it. US Navy Photo

An American with Royal Navy panache and style. The legendary US Navy Landing Signals Officer, Lieutenant Richard (Dick) C. Tripp, aboard the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown, lands on a Grumman F6F-3 Hellcat wearing nothing but tennis shoes and flowered boxer shorts. Dick Tripp “batted” in more than 10,000 carrier deck landings from 1943 to 1945. Tripp died in 1990. Yorktown was the second of 24 Essex-class aircraft carriers built during the Second World War for the United States Navy. She is named after the Battle of Yorktown of the American Revolutionary War, and is the fourth US Navy ship to bear the name. Yorktown was decommissioned in 1970 and in 1975 became a museum ship at Patriot’s Point, Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. She is a National Historic Landmark. Other Essex-class carriers include a list of some of the most historic and legendary ships of the war: Intrepid, Hornet, Franklin, Ticonderoga, Wasp, Lexington, Princeton and Shangri-la. US Navy photo.

Another image of the legendary Dick Tripp. Here he shows his style not only with hand motions, but with fashion, sporting coveralls, sock feet, aviator glasses and a do-rag. “The guy was damned near magic,” said naval airman Jean Balch, a radioman in a Curtiss SB2C Helldiver. “Dick Tripp, for my money, was the best LSO in the whole Pacific.” Tripp, by all accounts was a piece of work. In On the Warpath in the Pacific: Admiral Jocko Clark and the Fast Carriers by Clarke Reynolds, Tripp at one time had to be disciplined for striking an officer: “A tipsy diminutive LSO Dick Tripp belted a rowdy commander from another ship for calling the Yorktown a ‘rusty dirty old boat.’ ” US Navy photo

Although this LSO is signalling “Cut” to this Grumman Hellcat, the pilot looks like he is banking to go round. This LSO has some Royal Navy style as he leans into the signal and the motion of the “cut” signal is so aggressive, that the paddle in his right hand is wrapped around his left shoulder all the way to the back of his right shoulder—big style points! It reminds me of Tiger Woods’ golf swing finish. US Navy photo

A US Navy Douglas TBD-1 Devastator from Torpedo Squadron VT-6 is guided to a touchdown by an LSO on a platform on the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) on 4 May 1942. We can see the net the LSO and his mate will dive into if need be. Since the aircraft is armed with a centre-line bomb, it was probably returning from an anti-submarine patrol. US Navy photo

The nonchalance of this US Navy LSO and his assistant with hands in his pockets lends credence to my theory that the American LSO lacks the willingness to put some style into his signals. This in no way is meant as a criticism, but rather an observation. US Navy photo

Conditions at the LSO’s station were often less than equatorial in temperature and the wind shield was a blessing. Here an F4U-4B Corsair from VF-53, The Blue Knights, drops on to the deck of the USS Essex off the coast of Korea in the cold winter of 1952. The LSO is bundled with insulated suit, boots, gloves and a fur-lined hood. The LSO can be forgiven for less than dramatic signals. US Navy photo

The job of an LSO or DLCO is extremely demanding, one that requires experience and many landings from both sides of the equation—in the cockpit and on the LSO platform. LSO apprentices, all of whom are highly experienced carrier pilots, must watch many hundreds of landings from the LSO’s side to understand the unique bond of trust between pilot and LSO and to learn a technique that is not truly or fully quantifiable—the art. Here American Navy pilots watch as a buddy uses paddles to bring home a squadron mate. US Navy photo

The jet age reduces the decision time for the LSO

The advent of the jet aircraft and its higher approach speeds shortened to time an LSO had to get the aircraft lined up and forced him to make decisions faster. For instance, jets had to be cut farther out than propeller-driven aircraft because they did not lose speed and settle as quickly. A difficult job just got more difficult. Here are a selection of photographs of some American LSOs bringing home jet aircraft.

It takes a lot of courage to stand close to the path or, as it seems in this case, IN the path of an oncoming fighter aircraft attempting to land within a few feet of you. Here, a Grumman F9F Cougar appears to line up on the LSO himself during Field Carrier Landing Practice (FCLP) at Naval Air Station Miramar, California, in 1954. The caption on this photo says that the LSO is giving the pilot the “Cut!” signal, but that would be to the other side of his body. It’s possible that, with his right foot in the air, he is just beginning his life-saving dive to the right to get out of the way.

Standardized Fleet LSO signals of the US Navy. Tommy H. Thomason wrote in Waving Them Aboard:

“The pilot first had to get to the start of the ‘groove’, which was where the LSO’s coaching began. At the risk of oversimplifying, the groove began a few hundred yards (less for propeller-driven airplanes) behind the ship, where the pilot had completed his turn from his base leg and was lined up and on speed at approach altitude in level flight. At this point, the LSO’s signals were visible and he began coaching the pilot as to height, airspeed, and line up in that order of priority...

The ‘slant’ or ‘tighten turn’ were used to coach the pilot as to line up, since—particularly with the F4U Corsair—the groove might well begin while the pilot was still turning to line up with the carrier. If the LSO thought that the pilot was in the process of making a good approach, he might therefore be given a Roger signal even while in the turn.

A wave off wasn’t necessarily indicative of a poor approach. In order to bring all the airplanes in as quickly as possible, the interval between them left little margin for a problem getting one out of the landing area. A wave off might therefore result from a foul deck [an aircraft still blocking the landing area or possibly a barrier problem-Ed] .The LSO might also realize that the deck movement, which he could feel before the pilot could see it, was out of sync with the airplane’s ability to settle into the landing area without being long (deck descending) or touching down too hard (deck rising).”

A United States Navy LSO of Korean War vintage signals the “cut” to a Grumman F-9F Panther. He wears a hand-painted coverall with a squadron tiger emblem and though it’s probably not him, he looks a lot like Dick Tripp in terms of style. US Navy Photo

As a McDonnell F2H Banshee rounds out after his approach he is right on line and gets the “cut” from this LSO. US Navy photo

An LSO turns to admire his work as Grumman S-2 Tracker of Anti-submarine Squadron VS-33 passes him on its way to trapping on board the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-12) in 1970. Hornet CV-12, an Essex-class carrier, was built in the Second World War and named in honour of USS Hornet (CV-8), the carrier which launched the Doolittle Raiders and was sunk at the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, the last US fleet carrier ever sunk by enemy fire. US Navy photo

Looking more like a 1980s stoner downhiller in a one-piece ski suit, or perhaps a mid-70s new wave band like Devo, this USS Yorktown LSO can be forgiven for looking like a London ponce in 1954 in his satiny coveralls with Day-Glo pink stripes, because he and his fellow LSOs are doing one of the most difficult jobs in the world of aviation. US Navy photo

This is a screen capture from the motion picture The Bridges of Toko-Ri, with Robert Strauss playing the part of the irascible and colourful LSO known as Beer Barrel wearing the same LSO suit that is worn in the previous photograph. The horizontal pink stripe and vertical yellow bars were designed to not only be seen, but to help pilots to better see the vertical and horizontal relationship of signals. Today, the LSO no longer gives hand signals, but guides by radio as the pilot keeps on the glide path using visual cues from a light known as the ball. When landing on a carrier today, there is a beam of light shining towards the incoming aircraft. The beam of light represents the perfect glide path / approach. When the pilot of the incoming aircraft looks directly at the beam it appears as a ball. When the pilot “calls the ball”, he has sight of the ball and is preparing to land. When the pilot is coming in, he is asked by the LSO to “call the ball,” which is just asking the pilot if he can see the ball and that he is on a safe glide path for the landing. The proper response from the pilot is to give the weight of his aircraft, and then “Roger Ball.”

US Navy Landing Signal Officer Lieutenant W.F. Tobin, on exchange, offers up signals to a French fighter landing aboard French carrier La Fayette, off Indochina, in 1953. Sadly, while acceptable to perhaps a European, the chin-strapped cap is just not cool enough for the macho job that is the LSO’s. Ten years later, US Navy LSOs would be working out of the Gulf of Tonkin 24 hours a day. Photo: United States Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation

While Dick Tripp earned style points in tennis shoes and flowered underwear, there are absolutely NO style points earned dressed like this American aboard the USS Midway in 1955. The head gear was experimental. Photo by Luis Marden, National Geographic

Lieutenant David McCampbell signals that the oncoming aircraft about to land on the USS Wasp is too low and needs to come up to get on the proper glide angle. If this was aboard a Royal Navy carrier, this signal would mean the exact opposite—you are too high, come down. US Navy Photo

An advertisement for General Electric radio/telephones depicts the drama of a Second World War Landing Signal Officer giving the “cut” signal to a landing fighter. In the background we see the carrier’s island flying the signal flag for the letter “F”, which is also the flag carriers fly when Flight Operations are underway. It is also the flag for the message “I am disabled; communicate with me”, but certainly not in this case. Image via www.vintageadbrowser.com

Landing Signal Officer Lt. J.G. Brian Felloney helps guide the pilot of an F/A-18F Super Hornet from the “Diamondbacks” of Strike Fighter Squadron One Zero Two (VFA-102) to land on the flight deck of USS John C. Stennis (CVN 74). Stennis was at sea conducting training exercises in the Southern California operating area. The modern LSO no longer uses his hands, paddles, bats or flags. He or she communicates directly with the pilot by radio calls and light signals. Carrier landings are so important to successful aircraft carrier deployments that there exist private companies in the United States who consult and train future LSOs. Carrier Landing Consultants, one of these training companies, has this to say about the role of the modern LSO: “LSOs watch aircraft to ensure their glideslope, airspeed, attitude and lineup are within normal parameters for a safe recovery on the carrier. Too steep and an aircraft might break when it lands. Too shallow and a jet might hit the back of the ship. Too fast and an aircraft can damage the arresting wires. Too slow and the aircraft might stall or settle. LSOs communicate to pilots with light signals and radio calls, ensuring a safe pass and a quick recovery. While aviation technology has advanced by leaps and bounds over the past century, the role of the LSO has remained. Technology can fail and the weather at sea can be unpredictable. When the conditions become the most challenging, the need for an experienced and highly trained LSO is at its greatest. The LSO community has left a long and distinguished history, and it has a bright future ahead” US Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 2nd Class (AW/SW) Jayme Pastoric

A covey of modern LSOs at sea aboard the nuclear carrier USS Harry S. Truman (CVN 75) evaluates the landing of an aircraft aboard the Truman. Gone is the flourish, the theatrical hand gestures and the lunging “cut” signals of the early days of carrier aviation, replaced by optical light systems, stop watches and radio calls. While the panache and style have disappeared from the LSOs bag of tricks, the practitioners of the art today still have to apply instantaneous decision-making, impeccable judgement, years of carrier flying experience, courage and, like James Michener’s quote in the beginning of this story, they can defer their job to no one. While the period of The Harry S. Truman and Carrier Airwing 3 were on a regularly scheduled deployment in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. US Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate Airman Ryan O’Connor.

![Standardized Fleet LSO signals of the US Navy. Tommy H. Thomason wrote in Waving Them Aboard: “The pilot first had to get to the start of the ‘groove’, which was where the LSO’s coaching began. At the risk of oversimplifying, the groove began a few hundred yards (less for propeller-driven airplanes) behind the ship, where the pilot had completed his turn from his base leg and was lined up and on speed at approach altitude in level flight. At this point, the LSO’s signals were visible and he began coaching the pilot as to height, airspeed, and line up in that order of priority...The ‘slant’ or ‘tighten turn’ were used to coach the pilot as to line up, since—particularly with the F4U Corsair—the groove might well begin while the pilot was still turning to line up with the carrier. If the LSO thought that the pilot was in the process of making a good approach, he might therefore be given a Roger signal even while in the turn. A wave off wasn’t necessarily indicative of a poor approach. In order to bring all the airplanes in as quickly as possible, the interval between them left little margin for a problem getting one out of the landing area. A wave off might therefore result from a foul deck [an aircraft still blocking the landing area or possibly a barrier problem-Ed] .The LSO might also realize that the deck movement, which he could feel before the pilot could see it, was out of sync with the airplane’s ability to settle into the landing area without being long (deck descending) or touching down too hard (deck rising).”](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1628706259368-T8478XLJBN9SPE63PZX4/BodyEnglish33.jpg)