FASCIST FLATTOPS

Somewhere 55 kilometres off the coast of Poland, beneath the dark, cold waters of the Baltic Sea, lies the colossal ghost of a haughty dream of world dominance. While fish sluggishly fin in and out of her silent spaces, silt settles like the dust of history over her rusting shoulders. It has been nearly seventy years since she last saw the light of day. And what an awful day that was.

She is Flugzeugträger (Aircraft Carrier) Graf Zeppelin, one of five aircraft carriers commenced by the navies of the two European fascist powers of the Second World War—Germany and Italy. Of the five attempted carriers, Graf Zeppelin came the closest to being operational. In the end, her only military accomplishment was a benefit to the Allies—keeping 30,000 tons of much needed steel from the U-boat builders of the Third Reich.

The concept of the aircraft carrier, while not new when the war began in 1939, could certainly be said to be untested. Carriers were a military weapon system about to prove their place at the top of the food chain, but for the undecided and the late-to-the-game navies of Italy and Germany, there was still plenty of heated debate and animosity within these services and without. The great carrier powers of the Second World War were three—the United States Navy, the Imperial Japanese Navy and the Royal Navy. They all had been in the game for a long time and had built relatively deep experience with technologies for deploying and operating carriers throughout their empires. In fact, it was the defence and extension of these very empires, stretched across massive expanses of open ocean from Scapa Flow to the Falklands, from San Diego to the Philippines and from Sakhalin to Sarawak, which gave impetus to the development of carriers and their supporting task forces. Carriers would be involved in the opening salvos of both the Pacific and the European wars—with HMS Courageous being torpedoed just a couple of weeks after the declaration of war, and Japanese carriers delivering a crippling but not fatal blow to the Americans at Pearl Harbor. Carriers would be in the thick of things in the closing weeks of the war in the Pacific, and by then had supplanted the heavy battleship as the most important weapon in any navy’s arsenal.

As mentioned, Germany came into the aircraft carrier game later than other countries with designs on the world. This was largely because her militaries (Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe) were prevented from doing so by the Treaty of Versailles—at least on paper. Of course, when the Nazis took control of the government, they largely thumbed their noses at the treaty that Germany had been forced to sign in 1919. Re-armament or “Aufrüstung” was conducted both under the noses of and in the face of the Allies.

In the summer of 1935, a new Anglo-German Naval Treaty gave Germany permission to construct new capital ships including aircraft carriers up to 38,500 tons displacement. It didn’t take long before Adolf Hitler announced plans to construct the first of four planned carriers – for the Kriegsmarine had been developing plans since 1934. In secret, a delegation of Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe officers visited Japan to obtain technology. There, they visited the recently completed IJN Akagi, one of the Japanese carriers that would launch aircraft in the attack on Pearl Harbor six years later. Along with the German lack of experience in the carrier business, came an even greater shortfall in appropriate aircraft for carrier operations. Both the Germans and the Italians chose to select aircraft from their air forces and modify them for carrier duty – a process that would prove, for the most part, unsatisfactory.

By 1937, plans had been largely completed, enough at least to lay down the keel on Slipway One at Kiel’s Deutsche Werke for an 861-foot-long fleet carrier called Flugzeugträger “A”. Work proceeded at full bore until the end of 1938 when, on 8 December, she was christened KMS Graf Zeppelin by Countess Hella von Brandenstein-Zeppelin, the daughter of the ship’s namesake—Count Ferdinand Zeppelin. Graf Zeppelin was then cut loose to slide down the slipway and into a launch basin at Deutsche Werke, Kiel. She was then attended by numerous tugs who shepherded her to a berth on a dock where she would be fitted up and readied for her shakedown cruise. Weeks after her launch, another carrier, known simply as Flugzeugträger “B”, was laid down and work commenced. The ship would be the second of the Graf Zeppelin class of carriers, and it is widely believed that at her christening she would carry the name KMS Peter Strasser, named after the First World War commander of Germany’s airships.

In September of 1939, Graf Zeppelin was, by all accounts, 85% complete when war broke out. With focus on other military events taking place, on the building of U-boats and the finishing of other capital ships, progress slowed until, in July of 1940, work was ordered stopped. Her life from this point forward would be a series of movements east and west across the Baltic coast of Germany and Poland—attempts to keep her out of bombing range mixed with rejuvenated periods of work to complete her. She would languish at wharfs and backwater anchorages from Gotenhafen to Kiel to Stettin until 1945, when the imminent threat of the advancing Soviet Red Army pushed her skeleton crew to scuttle her in shallow water, a rusting mountain of 30,000 tons of steel sitting on her keel at a bend in the brackish Parnitz River.

Like almost all capital ships of the Kriegsmarine in the Second World War, her career, had she become operational, would have been short and not worth the effort. In the war, German battleships and heavy cruisers were either hounded to death by the Royal Navy surface fleet or forced to hide deep in Norwegian fjords with little to show for the millions upon millions of reichsmarks spent on their construction. Graf Spee was scuttled in the estuary of the River Platte. Bismarck was sunk in the North Atlantic, Tirpitz spent the war hiding. Gniesenau was scuttled. Prinz Eugen was a gunnery platform used in support of ground troops, and in the end, was towed to Bikini Atoll in the Pacific where she survived two nuclear bomb tests. When the most celebrated engagement of Kriegsmarine surface ships was the “Channel Dash”, the escape from Brest to Brunsbüttel Locks at the mouth of the Kiel Canal via the English Channel, you know your plans for naval domination are hopeless. The fate of Graf Zeppelin would have been no different. And the Germans knew it.

Despite a later attempt to complete Graf Zeppelin, she would end her war service a rusting hulk which not only kept 30,000 tons of steel from Admiral Dönitz’s submarine building program, but which eventually fell into the hands of the Red Army. The two other attempts to build a carrier for the Kriegsmarine also failed, though less spectacularly. Flugzeugträger “B” (Peter Strasser) was scrapped where it sat on the slipway, less than 50% complete. Another attempt, a conversion of the brand new heavy cruiser KMS Seydlitz to a carrier, also failed. She had her superstructure removed at great cost and her guns deployed to the Atlantic Wall, and that being done, spent the rest of the war as did Graf Zeppelin—a white elephant and somewhat of an embarrassment.

In December of 1936, the keel of the German aircraft carrier (Flugzeugträger) Graf Zeppelin is laid down on Slipway One of the Deutsche Werke shipyard in the city of Kiel, Germany. She was given the construction number 252 by Deutsche Werke. Photo: Bundesarchiv via ww2db.com

By late March of 1937, progress has been made and the hull begins to take shape. Construction work on the mighty aircraft carrier took more than two years. Construction of capital ships of the Kriegsmarine, including failed projects like Graf Zeppelin, could only have taken place prior to hostilities as they would have been large targets exposed to bombardment for too long a time. All of the largest and most modern capital warships of the Kriegsmarine (Bismarck, Tirpitz, Admiral Graf Spee, Admiral Scheer, Gneisenau, Scharnhorst, Prinz Eugen, Blücher, Admiral Hipper, Lützow, etc.) were constructed from 1931 to 1938. The German Navy was never able to build another large warship for the duration of the war, concentrating on the rapid building of U-boats instead. Photo: Bundesarchiv via ww2db.com

Early wind tunnel testing of a Graf Zeppelin model—likely to test whether smoke from the stack would impact flight operations when the ship was turned into the wind for launch and recovery. Clearly, the design dispersed the smoke overhead any activity on the deck. These tests also were important to discover sources of turbulence generated by the bow, stern and superstructure which may have affected flying operations. Photo via dr.de

Related Stories

Click on image

Taken in March 1937, this photo, looking forward to the bow of Graf Zeppelin on the starboard side, shows she is beginning to rise from Slipway 1 at the Deutsche Werke Shipyard in Kiel. At the top of the image we can see two other dry dock chambers—desirable targets for Bomber Command aircraft when hostilities began. The hull at this point is simply known as Flugzeugträger “A”, meant to be the first of two carriers of the class. Grand Admiral Eric Raeder’s dream was to have four fleet carriers similar in size to Graf Zeppelin. She would not officially become Graf Zeppelin until the day of her christening two years later. Photo: Bundesarchiv via ww2db.com

Scaffolding now rises with the hull as Flugzeugträger “A” takes shape at Deutsche Werke. Deutsche Werke was a large German shipbuilding company, owned by the government of the Weimar Republic, resulting from the merger of a group of Kiel-based shipbuilders in 1925. Its headquarters were in Berlin. From the outset, Deutsche Werke built merchant ships, but production shifted to large military vessels with the rise of the Nazi party and its military buildup. Photo: Bundesarchiv via ww2db.com

On a rainy November day in 1938, just a few weeks before launch, with fresh paint applied and much of her scaffolding gone, crews rush to tidy her up for the big day. The rectangular opening visible in this image is for the exhaust stack from the boiler rooms below. Photo: Bundesarchiv via ww2db.com

A photo taken a couple of weeks before her launch reveals her fine coat of paint and the steel base of her flight deck. The two square openings are for two of twin-barrelled 15 cm guns—the largest in her considerable weaponry. These guns were later installed, but when work was halted later in 1940, her guns were removed and used as coastal artillery in Norway. Photo: Bundesarchiv

On 8 December 1938, Adolf Hitler and his chiefs of staff (corpulent Goering on the right, Admiral Eric Raeder on left) visit Hamburg for the christening of Graf Zeppelin. Many thousands were on hand the day of the launch, while Hitler and his retinue enjoyed the scene on a raised and decorated platform. Photo: Bundesarchiv

On the day of the christening and launch of Graf Zeppelin, Hitler struts with a haughty looking bunch, between the dry dock where the ship awaits and a large honour guard of Luftwaffe soldiers. It is amusing to note that the group, in trying to be seen with Adolf Hitler, Hermann Goering, Martin Bormann, Field Marshal Keitel and Admiral Raeder, seems to be squeezing the SS officer on the left, forcing him to walk precariously on the top of the dry dock wall. At first I thought this guy was a Kriegsmarine officer, but reader Mark Neilans pointed out that is was an SS officer (possibly Sepp Dietrich who was there that day) and that he deserved it! This image was taken a few metres further on than the previous photo. Photo: Bundesarchiv via MaritimeQuest.com

Honoured Nazi military and political guests attend the christening and launch of Graf Zeppelin in Hamburg. Flugzeugträger “A” was christened Graf Zeppelin by Hella von Brandenstein-Zeppelin, the daughter of Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, for whom the ship was named. As hopeful as this event was for the future of naval aviation in Nazi Germany, it was literally the high point. The great ship would not get much farther than a few hundred kilometres from the dry dock she was built in for the rest of the war. Photo: Bundesarchiv

To the Nazi salutes and “Sieg Heils” of many thousands of soldiers, sailors, airmen and civilians, and with newsreel cameras whirring, Flugzeugträger Graf Zeppelin begins her slide down Slipway One at the Deutsche Werke shipyard on 8 December 1938. On her starboard side rests the hull of the Kriegsmarine supply ship Franken. After its launch in 1939, Franken was towed to Copenhagen for finishing. Franken was not completed until 1943. She operated only in the Baltic Sea, supplying the cruiser Prinz Eugen, and was broken in two and sunk by bombs from Soviet aircraft in 1945. Photo: Bundesarchiv

The newly finished and just christened hull of Fleugzeugtrager Graf Zeppelin slides majestically down the ways while the dry dock is lined with sailors of the Kriegsmarine and families of the men who worked on her construction. Judging by the Nazi flag on her bow, which is blowing towards the stern, her progress down the ways was fairly gentle. A second carrier of the Graf Zeppelin class was already underway. Photo: Bundesarchiv

Another photo, taken at the same moment as the previous photo, reveals the massive crowd of military and civilian spectators who were in attendance for this event. Photo: Bundesarchiv

As Graf Zeppelin slides into the water for the first time, diminutive but powerful harbour tugs surround her to slow her slide and nudge her toward a berth and the finishing dock. Photo: Bundesarchiv

Kiel harbour tugs nudge the colossus now known as the Graf Zeppelin towards a berth dockside where she will undergo transformation into a working aircraft carrier. Photo: Bundesarchiv

With timbers from her launch still floating in the launch basin at Kiel, tugboats manoeuvre the pristine and flag bedecked hull of the newly christened Flugzeugträger Graf Zeppelin to a dock where crews can begin her superstructure and systems fit up.

The Kiel harbour tugs, Auguste and Emil, pull the hull of Graf Zeppelin as another tug pulls amidships. Photo via battletankbelgie.be

A view of the shapely stern of Graf Zeppelin as she is manoeuvred to her berth. Note the garlands and rather old-style anchor, likely ready in case of an emergency. Just the previous year, when the battleship Gneisenau was launched from the same slipway, harbour tugs were unable to arrest her backward slide across the launch basin and the ship collided with the far embankment. The system for braking the launch worked well with Graf Zeppelin. The tops of her twin rudders can be seen in this image, but would be deeper with the additional weight of her superstructure, guns, systems and fuel. Photo: Bundesarchiv

Graf Zeppelin’s flight deck and catapult systems are added dockside at Kiel in 1939. Construction carried on apace throughout that summer and into 1940. Photo: Bundesarchiv

A close-up view of the work on Graf Zeppelin, showing the work offices and shelters. Photo: Bundesarchiv

A view showing progress late in 1939, with work beginning on the island superstructure on the starboard side. After hostilities began with France and Great Britain in September, however, further progress was stopped due to political pressures within the Kriegsmarine and without. Admiral Kerl Dönitz felt that the resources could be better spent elsewhere—namely on his U-boats and Hermann Goering wanted nothing to do with carrier aviation at all. By this time, naval air operation from carriers was still a concept that had not yet been proven in actual combat. Photo: Bundesarchiv

The only photo I could find on the internet of Flugzeugträger “B”, the sister ship of Graf Zeppelin was the tiny inset above. This carrier would never be finished, and would be scrapped on the slipway at Deutsche Werke. Though she never got a name, it is widely believed that she would have been named Flugzeugträger Peter Strasser, after the commander of the Imperial German Navy’s zeppelin fleet in the First World War. Work began on Flugzeugträger “B” (Peter Strasser) in early 1939, but was halted in September 1939 when war was declared. Peter Strasser was completed up to the armoured deck. It sat rusting on the slipway at Deutsche Werke until late February 1940 and was ordered scrapped. The main image is of Graf Zeppelin, but represents the degree of completion her sister ship had reached before cancellation. The scrapping was completed in just four months. Photo: Bundesarchiv

An RAF reconnaissance photo of Bremen harbour in 1942 captures the half finished heavy cruiser KMS Seydlitz about to undergo conversion to an aircraft carrier. The decision was taken to provide accompanying air support for other already finished capital ships. Upon completion, she was to be renamed KMS Weser. In Bremen, work began to take down the superstructure so recently finished. The guns were removed to become coastal guns at Lorient on the Atlantic Wall. By the end of the year, all of her upper works had been removed and Seydlitz left Bremen for the Schichau Shipyards in Königsberg. At the beginning of 1943, recent naval defeats of large Kriegsmarine capital ships caused an angry Hitler to order the decommissioning of all capital ships and the cessation of work on future major naval projects. Not much work had taken place since her arrival at Königsberg and she stayed there until the Soviets threatened to capture her. German demolition crews scuttled her. She was refloated after the war with plans for the Russians to finish her. Eventually she was scrapped in 1950–51. Photo: YouTube

KMS Seydlitz (the future Weser) in Bremen with all of her superstructure, except her funnel, removed in preparation of the construction of a flight deck. The conversion would be done in Königsberg. Photo via YouTube

An informative and superbly written article appearing on the web page of Innerspace Explorers, the dive group that first visited the wreck of Graf Zeppelin, offers this explanation of the overly-complicated launch system to be used on the carrier:

“Graf Zeppelin had three electrically-operated elevators positioned along the flight deck’s center-line: one near the bow, abreast the forward end of the island; one amidships; and one aft. They were octagonal in shape, measuring 13 m (43 ft) x 14 m (46 ft), and were designed to transfer aircraft weighing up to 5.5 tons between decks.

Two Deutsche Werke compressed air-driven catapults were installed at the forward end of the flight deck for power-assisted launches. They were 23 m (75 ft) long and designed to accelerate a 2,500 kg (5,500 lb) fighter to a speed of approximately 140 km/h (87 mph) and a 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) bomber to 130 km/h (81 mph).

A dual set of rails led back from the catapults to the forward and midship elevators. In the hangars, aircraft would have been hoisted by crane onto collapsible launch trolleys. The aircraft/trolley combination would then have been lifted to flight deck level on the elevator and trundled forward to the catapult start points. As each plane lifted off, its launch trolley would have been caught in a metal “basket” at the end of the catapult track, lowered to the forecastle on “B” deck and rolled back into the upper hangar for re-use via a secondary set of rails.

The catapults could theoretically launch nine aircraft each at a rate of one every thirty seconds before exhausting their air reservoirs. It would then have taken 50 minutes to recharge the reservoirs. When not in use, the catapult tracks could be covered with sheet metal fairings to protect them from harsh weather.

It was intended from the outset that all of Graf Zeppelin’s aircraft would normally launch via catapult. Rolling take-offs would be performed only in an emergency or if the catapults were inoperable due to battle damage or mechanical failure. Whether this practice would have been strictly adhered to or later modified, based on actual air trials and combat experience, is open to question, especially given the limited capacity of the air reservoirs and the long recharging times necessary between launches. One advantage of the system, however, was that it would have allowed Graf Zeppelin to launch and land aircraft simultaneously.”

Innerspace Explorers also explain the flight testing going on simultaneously with the construction: “In 1937, with Graf Zeppelin’s launch scheduled for the end of the following year, the Luftwaffe’s experimental test facility at Travemünde on the Baltic coast began a lengthy program of testing prototype carrier aircraft. This included performing simulated carrier landings and take-offs and training future carrier pilots.

The runway was painted with a contoured outline of Graf Zeppelin’s flight deck and simulated deck landings were then conducted over an arresting cable strung width-wise across the airstrip. The cable was attached to an electromechanical braking device manufactured by DEMAG. Testing began in March 1938 using the Heinkel He 50, Arado Ar 195 and Ar 197. Later, a stronger braking winch was supplied by Atlas-Werke of Bremen and this allowed heavier aircraft, such as the Fieseler Fi 167 and Junkers Ju 87, to be tested. After some initial problems, Luftwaffe pilots performed 1,500 successful braked landings out of 1,800 attempted.

Launches were practiced using a 20 m (66 ft) long barge-mounted pneumatic catapult, moored in the Trave River estuary. The Heinkel-designed catapult, built by Deutsche Werke Kiel (DWK), could accelerate aircraft to speeds of 145 km/h (90 mph) depending on wind conditions. Test planes were first hoisted by crane onto collapsible launch carriages in the same manner as intended on Graf Zeppelin.

The catapult test program began in April 1940 and, by early May, thirty-six launches had been conducted, all carefully documented and filmed for later study: seventeen by Arado Ar 197s, fifteen by modified Junkers Ju 87Bs and four using a modified Messerschmitt Bf 109D. Further testing followed and by June Luftwaffe officials were fully satisfied with the catapult system’s performance.”

The Luftwaffe experimented with arrested carrier landings using three modified and obsolete Avia Bk-534 biplane fighters which had been confiscated from the Czechs. The Luftwaffe Resource Center at WarbirdResourceGroup.org explains: “The aircraft were given spools for catapult launching, a folding hook for arrested landings and thus equipped they were tested in 1940 to 1941 period. The airframe structure was not designed to withstand the concentrated loads of arrested landings, and the A-frame hook got pulled out from the fuselage on several occasions and the carrier-borne career of the Bk-534 fighter ended even before the German aircraft carrier project was abandoned.” Photo: topsid.com

Also used for launch and recovery systems tests for the new Graf Zeppelin was the Arado Ar.96 advanced trainer. The six aircraft that were used for the tests were designated as Arado Ar.96B-1s. Not all were equipped with both the catapult attachment points and arresting hooks. A crane has hoisted this Arado to test its fit to a catapult cradle, which will be the system for launching from Graf Zeppelin. Two of the Arados (CD+OA (above) and PH+GZ) flew to Italy in 1943 and demonstrated the technology to the Regia Aeronautica at Perugia San Egidio.

Graf Zeppelin’s primary weapons would be the aircraft of its carrier air group—originally designed to be 42 aircraft strong—12 Ju-87C Stuka dive bombers, 30 Messerschmitt Bf-109T fighters and Fieseler Fi.167 biplane torpedo bombers—all either specifically designed or modified for carrier use. Later on, during the building of Graf Zeppelin, the complement was redesigned to include 30 Stukas and 12 109s, with the promising Fieselers eliminated altogether. The Junkers Ju-87C Stuka (for Sturzkampfflugzeug) dive bomber, which would soon terrorize continental European countries under the boot of the Nazis, was chosen for its robust structure, which could be redesigned for carrier use—including wings that folded at the kink in the inverted gull wing and the addition of a tail hook for arresting landings. Photo via SinoDefenceForum.com

A navalized Stuka extends one of its folding wings. By September of 1939, as the war was just beginning, one aircraft carrier wing, known as Trägergruppe 186, had been formed by the Luftwaffe. It was composed of three squadrons equipped with Messerschmitt Bf-109 and Junkers Ju-87C aircraft. Photo via Pinterest.com

A head-on view of the same prototype Junkers Ju-87C Stuka from the previous photo, showing clearly how much space would be saved if the dive bomber’s wings could be folded. The wings were hand rotated 90 degrees and then folded rearward. Photo via Pinterest.com

A navalized (with a tail hook) Stuka is flung into the air during a systems test from a barge off the Baltic coast at Travemünde, near Lübeck. Unlike American, British and Japanese carriers of the day, which actually flew their aircraft complement off their flight decks, the Graf Zeppelin was to utilize an overly complex cradle and catapult system similar to those systems used to launch reconnaissance aircraft from capital ships such as Bismarck. The launching aircraft had to be craned onto a cradle specifically designed for the type. The cradle was launched by a compressed air catapult and was arrested at the end of the stroke, allowing the aircraft to continue on in flight. The cradle would then be shuttled back, then down an elevator to be mated with another Stuka, while the next cradle was launched from the flight deck. Photo via wehrmacht-history.com

With the construction of the Graf Zeppelin already underway in early 1937, the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (the German Ministry of Aviation) issued a specification and request for designs for a carrier-based torpedo bomber for use on the two Graf Zeppelin class carriers. Two aircraft manufacturers, Fieseler and Arado, were issued the specification—requesting an all-metal biplane aircraft with a minimum top speed of 300 kilometres per hour (186 mph) and minimum range of 1,000 kilometres. The Fieseler designed Fi-167, which easily won over the Arado Ar-195, exceeded the specs in many areas. It was faster at 325 kilometres per hour, and could carry twice the required payload. Like its stablemate, the amazing STOL-capable Fieseler Storch, the Fi-167 could land almost vertically on a carrier underway. The crew could jettison the landing gear for an emergency ditching and flotation chambers in the wings allowed the aircraft to remain afloat long enough for the crew to escape to their life raft. Photo: Bundesarchiv via Wikipedia

Only 14 Fieseler Fi-167 aircraft were ever built—two prototypes and 12 production aircraft. One gets a good idea of the size of the big biplane with these ground crew standing beneath the port wing while loading bombs. Production of the aircraft was halted when construction of Graf Zeppelin was stopped in 1940. The 14 constructed aircraft were absorbed by the Luftwaffe. When construction of Graf Zeppelin resumed in 1942, the Junkers Ju-87C assumed the air group responsibilities of the Fi-167 as a torpedo and reconnaissance aircraft. The small number of Fieselers built did however make an impact, serving with the Croatian Air Force at the end of the war, the Royal Romanian Air Force and post war with the Yugoslav Air Force. With the Luftwaffe, it was used as a test bed for landing gear configurations. The low landing speeds hampered true testing of gear, so the lower wings were removed outboard of the gear legs to allow a harder landing. Its STOL and rough field capabilities made it, like the Westland Lysander of the Royal Air Force, excellent for delivering ammunition and other supplies to besieged Croatian army units. One Fieseler Fi-167, operating on such a resupply operation, was set upon by no less than five RAF P-51 Mustangs. Before it was shot down, the rear gunner managed to shoot down one of the Mustangs, one of the last biplane kills of the war. Photo via warships1discussionboards.yuku.com

A prototype Fieseler Fi-167 with civil registration (Fieseler construction number 2501) shows us the large vertical stature of the aircraft. Photo: LuftArchiv.de

The Arado Ar-197 was the other contender for a ship borne torpedo bomber. It was rejected in favour of the Fieseler, but by the time the Graf Zeppelin was to be completed, both aircraft would have been outclassed by advanced monoplane fighters. Neither went into full production. Photo via sas1946.com

A Messerschmitt Bf-109T (Luftwaffe code WL-IECY, Werke Number 1781), the navalized variant of the ubiquitous German design, was first requested by the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (the German Ministry of Aviation) in the fall of 1938, just months before the launch of Graf Zeppelin. The Messerschmitt Bf-109T (for Träger—German for carrier) was nicknamed “Toni” by its pilots. It was a highly modified 109E (Emil). The mods to the basic 109E included increasing the wingspan to 36.35 feet from 30 feet, adding an arrestor hook (attached directly to a strengthened frame 7 of the rear fuselage) and connectors for a catapult launcher. The flaps, ailerons and slats were all increased in size to ease carrier takeoff and landings. Photo via topsid.com

A blurry but informative view of the Messerschmitt Bf-109T, showing its enlarged flap and aileron areas and tail hook for arrested landings. Photo via topsid.com.

A Messerschmitt Bf-109T is catapulted from a barge during a test, with flaps set for takeoff. It nears the end of the stroke where the cradle will be arrested and the 109 will fly on over the Baltic. Messerschmitt Bf-109T TK-HM is a T-1 variant, without the tail hook as it would be landing at the test facility at E Stelle See (Test Centre Sea) at Travemünde-Priwall. Initial landing and arrestor wire tests were carried out in 1939 using the same aircraft. Photo via geocities.ws

A moment after its catapult launch from a barge, we see the Messerschmitt Bf-109T-1 Toni flung into the air, as the cradle comes to a stop at the end of the stroke and collapses. In this image we can clearly see the connector devices under the fuselage design to hook into the catapult cradle. Tests were carried out in 1940 in the same Travemünde area, on the Baltic Sea near Lübeck, in which the Stuka launches were conducted. Photo: Messerschmitt-Bf109.de

Two profiles of carrier-based Messerschmitt Bf-109T “Tonis” with arrestor hooks and catapult cradle connectors. Images via wingspalette.ru; illustrations by Teodor Liviu Morosanu

Graf Zeppelin receives a “clipper stem”, or Atlantic bow on the Kiel dockside where much of her fit-up was performed before construction was halted (for the first time) in 1940 soon after the outbreak of the Second World War. The bow was a modification to the original design to allow her better performance in the high seas of the Atlantic. Photo: Bundesarchiv

Graf Zeppelin’s Atlantic bow nears completion at Kiel in late March 1940. Photo: Bundesarchiv

A photograph of Graf Zeppelin in June 1940 showing tremendous progress—with radio masts, island superstructure, gun tubs, casements and guns and other systems now in place. Photo: Bundesarchiv

Beginning to show signs of neglect, the sad hulk of Graf Zeppelin rusts dockside at Stettin’s Hakenterrasse where she was towed for safekeeping. At this point, her gun casements and guns have been removed and sent to Norway for coastal defence. For most of her short life, Graf Zeppelin was manned by a skeleton crew who kept her internal systems oiled and in basic working order, hoping one day that the Kriegsmarine would find the budget, the time and the unmolested space to finish her and put her to sea. Her aggressive looking Atlantic prow would never see stormy seas of any kind and she was destined to pass her military career moored in backwater rivers and harbours. Photo via lasegundaguerra.com

A personal snapshot of Graf Zeppelin taken from the sidewalk on the Hakenterrasse (Chrobry Embankment) in Stettin in 1941. Photo via lasegundaguerra.com

Another photograph taken from the promenade at the Hakenterrasse as curious citizens come to take a look at the colossus. Photo via lasegundaguerra.com

A rare colour photo (possibly a postcard) of Graf Zeppelin on the Hakenterrasse at Stettin alongside training ships of another era. Even the sail-powered training ships have dazzle paint camouflage to help hide them, while the massive carrier Graf Zeppelin simply rusts, posing no threat to the Allies. Photo via MarineForum

A group of soldiers or perhaps naval cadets line the rail as their ship maneouvres to dock on the Hakenterrasse in Stettin. Judging by the massive shrouds coming down from the right, this is one of the tall ship training vessels tied up at the dock, which are visible in the previous photo. Photo via lasegundaguerra.com

Either this photographer did not want to be seen taking this snapshot, or perhaps he or she was just trying to make a pretty picture. In the following aerial photograph we can see the exact spot where the photo was taken—behind the trees seen off Graf Zeppelin’s starboard bow. Photo via geocaching.com

A reconnaissance photo shows Flugzeugträger Graf Zeppelin moored on the Oder River at Stettin’s Hakenterrasse in 1941, sometime between June 1941 when she arrived and November of that year when she was towed to Gotenhafen (now Gdynia, Poland). Photo via wwiivehicles.com

Graf Zeppelin docked in Gdynia, Poland (Gdańsk/Danzig) in 1942, covered in camouflage netting. Photo via wolneforumgdansk.pl

A view of the port side of Graf Zeppelin resting in a Deutsche Werke dry dock at Kiel in March of 1943 after work had resumed in early December of 1942. Photo: Bundesarchiv

An aerial view of Graf Zeppelin moored in a backwater of the Parnitz River in 1943, not far from the Baltic Sea coast. Her decks look as if they are being used for storage. Graf Zeppelin was, for a time, used as a floating storage facility for hardwood. This is the same spot where she would be found at the end of the war and where she would be scuttled and then raised by the Soviets. Photo via Flickr

There are two images of Graf Zeppelin, taken during the last two years of her Kriegsmarine life, that were taken from an orbiting biplane. They show an almost post-apocalyptic scene of Graf Zeppelin sitting at a bend in the Parnitz River. There is not a raft, tender or lighter to be seen. There’s not even a road or rutted trail to her mooring. She sits massively and hauntingly silent, as if humans have vanished from the face of the earth.

After two years languishing at her river bend mooring, the Red Army was close to overrunning Stettin. German demolition crews detonated depth charges and opened her sea cocks. She settled just a few metres onto the muddy bottom of the river, awaiting the arrival of the Russians.

A pilot and photographer fly over the forgotten hulk of Graf Zeppelin moored in the Parnitz River near Stettin. Photo via Flickr

Another photo, likely from the same aircraft as the previous photo, shows a very lonely Graf Zeppelin spending her last days in a shallow backwater surrounded by swampy country—a sad ending for a colossus meant for the open Baltic Sea and Atlantic Ocean. Photo via Flickr

By August of 1945, Russian marine experts finished an assessment of the damage, made appropriate repairs, pumped out the flooded spaces and refloated her. She was towed to Swinemünde and shortly thereafter taken on strength with the Soviet navy. The Russians briefly considered finishing her and employing her as an aircraft carrier, but instead she was reclassified in 1947 as an “experimental platform” and renamed PB-101 (Floating Base 101). In mid-August of 1947, she was towed from her mooring at Swinemünde to the open Baltic Sea. A number of vessels escorted her to her gravesite, where she would undergo explosive and aerial bombing tests. An attempt to anchor her to the bottom failed when her chain broke. Now it was imperative that she be dispatched before she drifted into shallower water.

A series of placed explosions were set off inside her, followed by both naval gunnery and aerial bomb attempts to sink her. Still she floated and continued to drift as weather worsened. The Soviet Navy then used destroyer-fired torpedoes to sink her, the first of which passed beneath her without detonating. Two more torpedoes fired at her starboard side did the trick and Graf Zeppelin listed to starboard and, down at the bow, slipped into eternity, one of the last vestiges of the dream turned into a nightmare.

A Red Army soldier explores the rain-soaked wooden deck of Graf Zeppelin after its capture in the Parnitz River near Stettin. As the Red Army neared the city if Stettin, in April of 1945, the skeleton crew assigned to the care of the carrier opened the sea cocks and flooded the lower spaces, causing the ship to settle into the muddy bottom of the shallow river. A demolition crew later rigged the ship’s interior with numerous explosive charges, ready to destroy vital equipment. The order was given on 25 April 1945, as the Russians entered the city, to detonate the charges. Smoke was seen to belch from her funnel for the first time, confirming that her boilers were now destroyed. The Soviets refloated the carrier and towed her to the Baltic and eventually to Swinemünde. It seems at this point they were not sure what to do with her—learn carrier technology from her or rebuild her and put her to the use she was intended for. In the end, they chose to use her as a target. Photo: lasegundoguerra.com

Graf Zeppelin photographed by a Red Army photographer sitting on the shallow bottom of the Parnitz River near Stettin, scuttled by her skeleton crew. Photo via wonferwaffe.ru

Graf Zeppelin in the Parnitz River in 1945. It is not clear whether this is before or after she was refloated. Photo via wonderwaffe.ru

The floating hulk of Graf Zeppelin, once the epitome of Nazi militarism, rocks with explosions from Soviet bombers off the coast of Poland in 1947. Photo: lasegundaguerra.com

The last photograph of Graf Zeppelin taken by a Soviet Navy photographer shows her sliding bow down on her starboard side into the choppy Baltic waters off the coast of Poland. She would not be seen again for another 60 years. Photo via lasegundaguerra.com

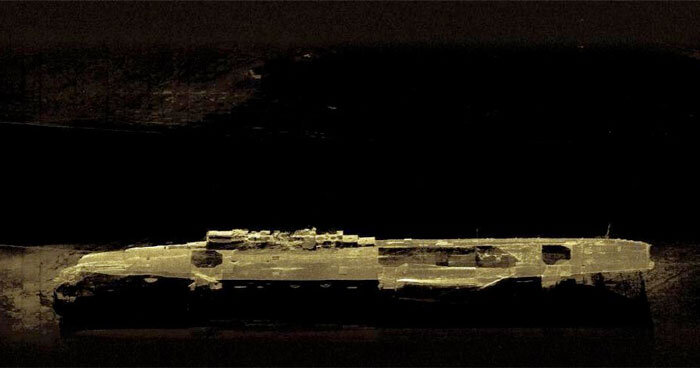

A haunting composite side scan sonar image of Graf Zeppelin lying upright on her keel at the bottom of the Baltic Sea, about 55 kilometres from Gdańsk, Poland (Danzig, Germany during the war). She was discovered in 2006, after 60 years, by the Polish petroleum company PetroBaltic, while sounding for oil deposits. For more photos of an Austrian diving expedition to Graf Zeppelin, click here. Image via Axishistory.com

The only operational images that exist of Flugzeugträger Graf Zeppelin are from the imagination of naval artists, for she was never underway at sea and never had an aircraft anywhere near her decks. In this dramatic depiction, a Ju-87C Stuka is launched, while a Messerschmitt Bf-109T Toni flies down the port side. Painting via tiexue.net

Graf Zeppelin steams through a menacing sky in this painting by prolific and talented Polish naval artist, Grzegorz Nawrocki. She never was able to offer up any menace to Allied forces, naval or otherwise. She ended her Kriegsmarine service as a derelict hulk tied up in a backwater river near Stettin, of so little threat to the Allies that they never bombed her, happy to let her float and keep 30,000 tons of steel out of the hands of the U-boat manufacturers. Painting by Grzegorz Nawrocki

A super-dramatic painting of Graf Zeppelin under attack by Russian aircraft (which seem to be getting the worst of it) whilst she spits two Focke Wulf 190 fighters off her catapults. The painting is from the box for Revell’s 1:720 model kit of Graf Zeppelin. Painting by D. F. via Revell

Two different box designs for Revell’s model of Graf Zeppelin. The top image, though more dramatic, shows the wrong fighter aircraft being launched from her catapults—Focker Wulf Fw-190 fighters instead of Messerschmitt Bf-109Ts.

Aquila and Sparviero

The Regia Marina, the navy of Fascist Italy also made two attempts to get into the carrier game—deciding for expediency to convert two identical ocean liners into carriers. The first, Aquila (Eagle), was a carrier of roughly the same size as Graf Zeppelin, utilizing the same catapult cradle launch system as the Germans were going to employ. Work on removing the superstructure from the liner Roma and building a fleet carrier on her hull began considerably later than work on the Graf Zeppelin—late 1941. Work continued over the next two years, and she was nearly completed when Italy signed an armistice in September 1943. Work was halted at this point and she joined Graf Zeppelin as an expensive white elephant. She was damaged in June of 1944 during an Allied bombing raid on Genoa harbour. Fearing the Germans might sink her to block the entrance to the harbour, Italian demolition divers scuttled her at her moorings. Aquila was raised after the war and towed to La Spezia in 1949, where for a brief period the Italians considered finishing her as a carrier or perhaps another warship. In the end, she was scrapped.

When it came to getting into the carrier game, Italy’s Navy, the Regia Marina, chose to go the conversion route on both of its aborted attempts to build an aircraft carrier. The Italian liner SS Roma, built for the shipping line Navigazione Generale Italiana in the Ansaldo Shipyards in Genoa, was selected in 1939 to provide the hull and propulsion for the new Italian fleet carrier Aquila (Eagle). When the Second World War broke out, Roma was laid up, taken on strength with the Regia Marina, and converted. It was a massive and ambitious conversion and might possibly have been a threat... one which, however, the Royal Navy would have eventually despatched. Photo via Egadi.wordpress.com

Aquila under construction in Genoa. In June of 1940, not long after Italy’s entering the war with the Axis powers, Benito Mussolini approved the conversion of the ocean liner Roma into an auxiliary carrier, with a flush deck and a small hangar. He and the Regia Marina had a change of plans at the beginning of 1941, just a couple of months after carrier-based Royal Navy Swordfish wreaked havoc on the Italian fleet at Taranto, when they decided on a considerably more ambitious conversion of Roma to a full-sized fleet carrier with a bigger air complement and speed that kept pace with the capital ships of the fleet. Photo via agenziabozzo.it

The nearly completed Aquila begins her slow decline after the capitulation of Italy. Though the sharp bow-like chine edge of the hull makes this appear to be the stem, it is in fact the round down at the stern of Aquila. Yard work on Aquila began in 1941 at the same Ansaldo shipyard in Genoa where Roma was built. Between the wars, the political and naval leaders heatedly debated the need for naval air capabilities and for carriers. In the 1930s it was thought that France would most likely become their future foe in a struggle for power in the region and paramount was parity with the French navy. The arguments against the need for carriers cited the fact that outlying islands in the control of Italy, such as Pantellaria and Sicily, would in effect be granite carriers. The aircraft carrier was, in those times, considered by more than just the Italians as an unproven concept, one however that would shortly demonstrate its worth in the Mediterranean Sea, when Royal Navy carriers supplied much needed defensive fighters to the beleaguered island of Malta. Photo: vetroplasica.it

A close-up of the port side of Aquila shows her anti-aircraft gun tubs, which never saw the installation of their heavy AAA weapons. By this time work had stopped and she was clearly in decline. Photo: vetroplasica.it

Photo via regiamarinaitaliana.it

Despite the obvious near-completion of Aquila, she spent her life tied up in Genoa, blanketed in camouflage netting. Photo via alieuomini.it

Work on Aquila was stopped by 1943 and she rusted in Genoa harbour, with a half-hearted attempt to conceal her identity with camouflage nets. Photo: via geocities.ws

A close-up of Aquila’s island superstructure draped with camouflage netting at Genoa in August 1943. Photo via alieuomini.it

Aquila at Genoa in 1945, looking pretty rough, but free of her camouflage nets at last. Photo via agenziabozzo.it

Aquila’s rusted and never manned island superstructure after being raised. Aquila survived the war, but not the scrapper’s torch. Photo via agenziabozzo.it

Aquila in La Spezia in 1950 for breaking up.

The rusted hulk of Aquila anchored at La Spezia in 1951, just before being scrapped. Photo: Pinterest

The SAIMAN 200 was one of the three aircraft being considered for aircraft carrier operations with the Regia Marina—as a trainer for carrier landings no doubt. The Regia Marina began searching for candidate aircraft for Aquila pretty late in the game. Throughout 1942 and 1943, aircraft evaluations were conducted at two air force test facilities at Perugia and Guidonia to find aircraft suitable for conversion to carrier use. The aircraft that survived this first round of development were the SAIMAN 200 (trainer), Fiat G.50 Freccia (Reconnaissance) and Reggiane Re.2001 Falco (Fighter) as potential candidates. Arrested landing tests with the Saiman 200 and the Fiat G.50 proved disappointing. Photo: avia-it.com

The Germans shared their technology and experience with the Italians—such as it was. Here a Luftwaffe Arado A.96.B-1 advanced trainer equipped with arresting gear demonstrates the technology for the Regia Aeronautica at Perugia. This aircraft (CD+OA) is the same aircraft pictured above in the section of this story dealing with German testing of systems. Photo via twelveoclockhigh.net

One of the fighter aircraft considered for carrier operations aboard Aquila and Sparviero was the Fiat G.50 Freccia ("Arrow"). First flown in February 1937, the G.50 was Italy’s first single-seat, all-metal monoplane with an enclosed cockpit and retractable undercarriage to go into production. Only one Freccia was modified, strengthened and tested for carrier use. It was intended for use as an armed reconnaissance aircraft. Photo: aaminis.myfastforum.org

Like many of Italy’s aircraft designs of the 1930s and 40s, the Fiat G.50 Freccia had a unique and strangely beautiful appearance. Of the nearly 800 Freccias manufactured, only a few were fitted with a tail hook for arrested landing tests. The results were disappointing.

A close-up of the Fiat G-50’s tail hook reveals that it was attached to the fuselage on either side of the tail—known as an A-frame arrestor hook. Photo via forum.1cpublishing.eu

Another failed attempt by the Regia Marina to build an aircraft carrier from a cruise ship was the auxiliary carrier Sparviero, built on the requisitioned hull of MS Augustus (above), the sister ship of Roma. Augustus was a combined ocean liner and world-cruise ship of 33,000 tons displacement. It was built in 1926 and operated by the Navagazione Generale Italiana which was forced by the Fascist government to merge with other line operators to become the nationalized Italia Line. Photo via histarmar.com.ar

Sparviero under construction at the Ansaldo Shipyard in Genoa, the same yard that had built her as Augustus. At the outbreak of the Second World War, Augustus and Roma were taken out of the line and then eventually taken over by the Regia Marina. Like her sister, the Augustus was converted into an aircraft carrier first named Falco and then later Sparviero. In 1944, both unfinished ships were confiscated by the Nazis—on 25 September 1944 Sparviero’s unfinished hulk was scuttled by the Germans, in an attempt to block Genoa’s harbour to the Allies. Following hostilities, what remained of Sparviero was raised and eventually sent to the scrap yard in 1946. The breaking up of Sparviero took until 1952. Photo via Wikipedia

Sparviero was the only Axis aircraft carrier that was put to an actual military use – sunk as a blockade ship by the Germans at the mouth of the harbour entrance at Genoa. Photo via agenziabozzo.it