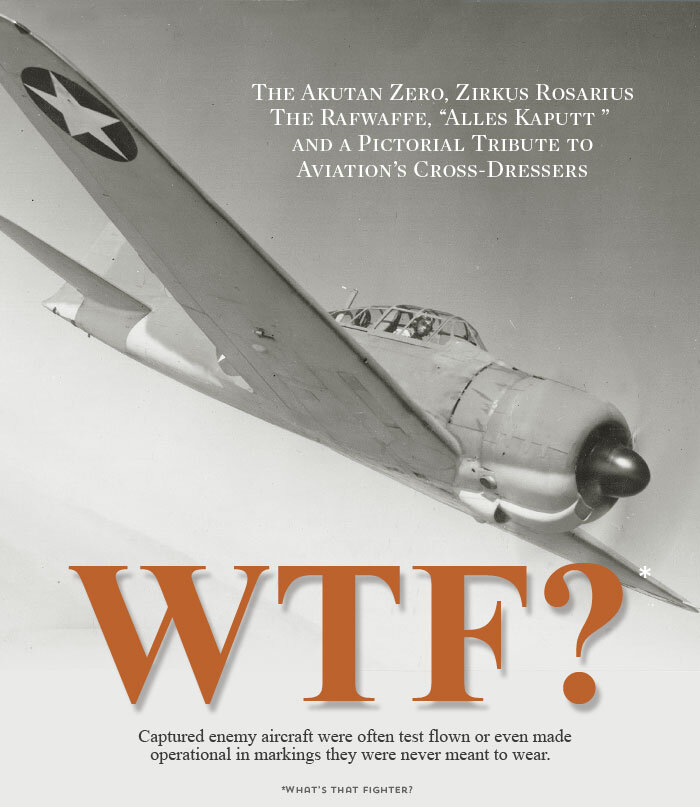

WTF? — Captured Enemy Aircraft

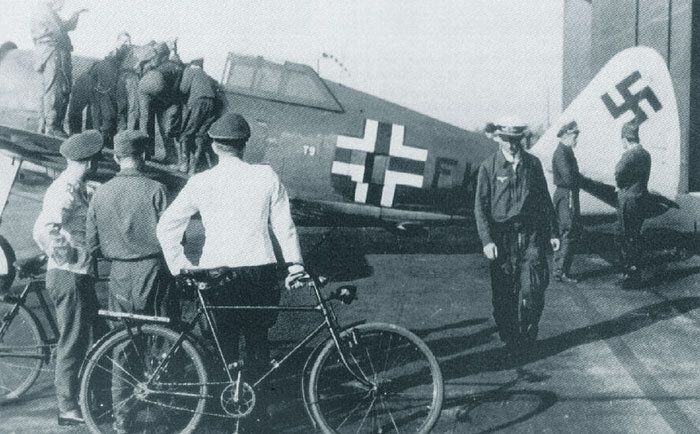

Over the past seven years of researching aviation stories on the web, I have kept a folder on my laptop dedicated to images of Second World War aircraft that had been captured and had suffered the indignity of being painted in the national markings of the enemy they were designed to fight and vanquish—like a Spitfire in the service of the Luftwaffe, a Zero in US Navy markings.

It has always struck me as undignified to see a Supermarine Spitfire wearing the hated Hakenkreuz (Swastika). Here was an aircraft which came to be the poster child for the strength of the British people and their ability to withstand the international bully that was Nazi Germany and now they had their hands and evil symbols all over it. To me, it was an outrage—like vandals spray-painting foul language on my mother’s car; as if some thugs had stolen Terry Fox’s van and painted 666 and neopaganist pentagrams on the sides.

But I soon learned that something I had originally thought was a rare exception was in fact a widespread, even systematic practice; not only in the Second World War, but from the very first time aircraft were pitted against each other in war.

One thing I know is that no fighter pilot relishes a fair fight. What they want above all is an advantage so that when they go toe to toe with the enemy, they are assured a much greater chance of the win than their opponent. Ever since David and Goliath, a fighter with a technological edge can triumph over a greater opponent. A Luftwaffe fighter pilot would rather engage a Fairey Battle than a Supermarine Spitfire, because the outcome would be weighted in his favour.

One of the simple ways to gain a technological advantage over an enemy is simply to know his weaknesses, be familiar with his blind spots, know what it is he can and can’t do. As the greatest war theorist of all time, Sun Tzu, wrote in The Art of War, “It is said that if you know your enemies and know yourself, you will not be imperilled in a hundred battles”. To this end, Allied and Axis nations alike in both World Wars slavered at the chance to take possession of one of their enemy’s flying machines and study it up close on the ground and in the air.

This folder of mine grew to hundreds of photographs and many links to the stories that explained the images. Over the years, I realized that many images that had been in this folder had long ago lost their links to the information I needed to explain them. But that didn’t stop me from putting together a pictorial essay. Here, for your enjoyment and edification, are nearly 250 of those images of captured aircraft wearing spurious markings. The truth is I could have made this a 500-image pictorial tribute, but one has to stop somewhere. These images have come from many sources over the years, and some links I have lost or have ceased to exist. I have written many of the accompanying texts, but in most cases, I have simply edited the texts that I found with the images (thank you Wikipedia). In each case I attempted to find additional sources on the web to back up the stories associated with each image.

In no way is this definitive. In no way is this a historical treatise or be-all and end-all of anything. In no way is this more than simply a visual tribute to all those aircraft that had to endure the indignity of enemy symbols. In many cases I may in fact have it wrong and I invite anyone to show me the correct information and I will update anything. In fact, for this I would be grateful. If anyone has issue with the use of any of this material if it is proprietary, let me know and I will remove offending images.

Let’s get the show on the road.

The First World War

During the First World War, advances in aviation were astounding... certainly greater than any “advances” on the ground. The difference between the aircraft at the outset and at the end of the war was nothing short of astonishing. It was easy for one combatant to gain air superiority over another with the simple application of a single new technology. The introduction of the Fokker Eindecker monoplane, with its ability to fire its machine gun forward through the propeller without deflectors on the propeller, was such an advance, the Allied air forces were at a distinct disadvantage for some months. The capture of an enemy aircraft on either side meant a chance to look closely at new technology like synchronizing propellers, new structural and engine technologies. The world of military aviation was advancing so fast that seeing what the other half was doing was as important as one’s own research.

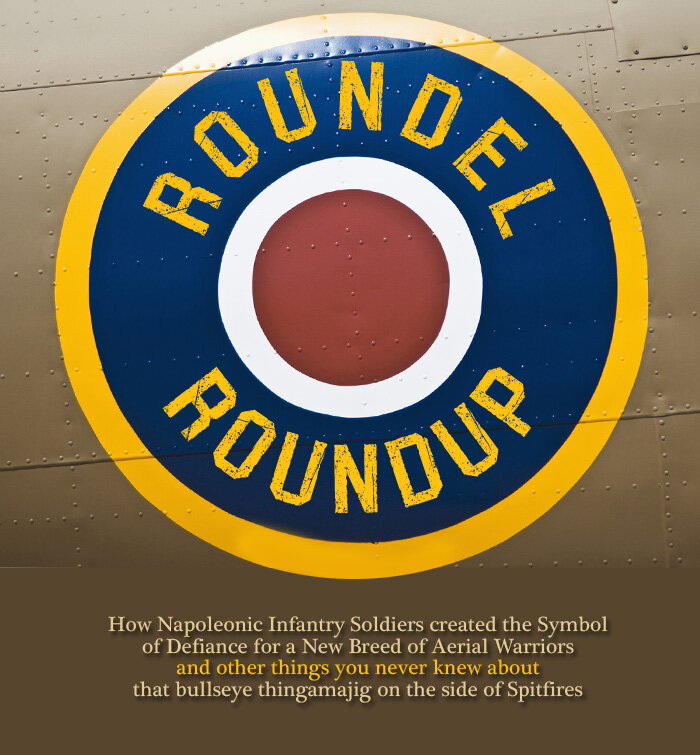

When the First World War started in 1914, it was the habit of ground troops to fire on all aircraft, friend or foe, which “encouraged” the need for some form of identification mark on all aircraft. At first, the Union Flag was painted under the wings and on the sides of the fuselages of Royal Flying Corps (RFC) aircraft. It soon became obvious that, at a distance, the St George’s Cross of the Union Flag could be confused with the Iron Cross that was already being used to identify German aircraft—particularly from below and against the glare of the sky. After a Union Flag inside a shield was tried unsuccessfully, it was decided to follow the lead of the French air force which used a circular symbol resembling, and called, a “cockade” (a rosette of red and white with a blue centre). The British reversed the colours and it became the standard marking on Royal Flying Corps aircraft from 11 December 1914, although it was well into 1915 before the new marking was used entirely consistently. The Royal Naval Air Service meanwhile briefly used a red ring, without the blue centre, until it was sensibly decided to standardize the RFC roundel for all British aircraft.

With ground troops and pilots on both sides attuned to identifying friend from foe based on these new national markings displayed on aircraft, it behooved pilots who were test flying enemy aircraft to mark them in the manner of their own armed forces. This had two benefits. Firstly, all test flights were conducted over friendly territory where ground troops would not take kindly to the flight of a single enemy-marked aircraft doing loops and rolls overhead. Marking the aircraft as friendly was simply common sense. Secondly, should a pilot testing an enemy aircraft, through disorientation, find himself over enemy territory and forced down, it would not result in a good outcome should he be flying an aircraft in the markings of the men who captured him. He would, no doubt, be considered a spy, and despite whatever he did to convince them otherwise, the pilot would likely be shot for wearing the markings of his enemy, much as ground troops posing as their enemies to gain superiority would be treated.

During the First World War, engine technology was still in its infancy. Rotary, in-line and radial engines could and often did, under many situations, simply stop in flight, either packed in, mishandled or roughly handled. Aerial battles were always conducted over enemy territory for one side or another. Aircraft in perfect condition, except for engine trouble, quite regularly were forced down and captured. In scouring the internet for photographic evidence of captured and remarked aircraft from the First World War, I was surprised at the wealth of spectacular images of both British and German aircraft in the hands of their adversaries. The internet is an amazing place to do a walkabout in search of information on a specific thing. The truth was that after just a few hours, I came across dozens of well documented cases of Sopwiths in Iron Crosses or Fokkers with roundels. I chose just ten of the dozens I found. Here, in no particular order, is a short visual tribute to the first military pilots and the captured aircraft they came to fly.

Es ist nicht ein “Pup”, es ist ein “Welpe”! A perfectly intact Sopwith Pup in Imperial German Air Service markings shares a flight line with German-built types in France. The Pup in this shot has been identified as the same Pup (N6161) featured in the following photo; however, to me, it seems they have different crosses on their fuselages, so I am not sure they are the same aircraft. Photo: theaerodrome.com

Related Stories

Click on image

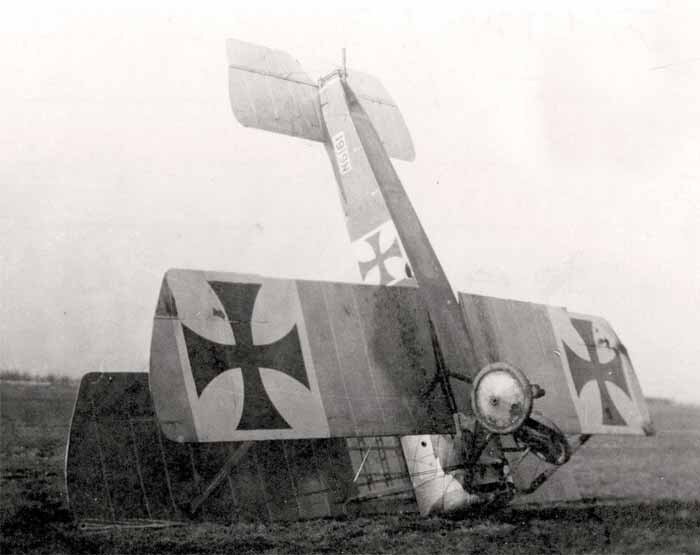

A Sopwith Pup (N6161), built by Sopwith at Kingston-upon-Thames, was brought down in nearly perfect condition near Blankenberghe on 1 February 1917 by Flugmeister Carl Meyer of Seeflugstation Flandern 1 and the pilot of the Pup, Flight-Sub-Lieutenant G.L. Elliott, was made a POW. Following evaluation and trials with the German Air Service, N6161 was then re-painted and given German markings. Not all post-capture test flights were successful with N6161, as indicated by this shot of her having broken her undercarriage and nosed over. It is interesting to note that though the markings were completely changed to those of Imperial Germany, the aircraft retained its RFC serial number. Photo: theaerodrome.com

We, Second World War warbird students, can be forgiven if our less-trained eyes call this a Fokker Triplane. It is in fact a Sopwith Triplane, sometimes called a “Tripehound” or just “Tripe”. This particular Tripe, Serial No. N5429, had previously seen service with No. 8 Naval and No. 10 Naval Squadrons, before being assigned to RNAS 1 Naval Squadron at Bailleul, France. While being flown by Flt. Sub-Lt J.R. Wilford of Naval 1, this aircraft was forced down by German pilot Kurt Wüsthoff (as his 15th victory), and captured on 13 September 1917. Following capture, this Tripe was painted over with German markings. Photo: theaerodrome.com

British officers get a close-up look at a captured German fighter, an Albatros DVa, wearing Royal Flying Corps roundels. This particular Albatros (Serial Number 1162/17–coded G56) was captured at St. Omer, France following an attack on a balloon of 38KBS and given captured serial number of G56. It was a former Jasta 4 aircraft flown by Feldwebel Clausnitzer. The DVa was brought down by a Lieutenant Langsland of 23 Squadron. After capture it was extensively tested and flown in the UK. Photo: theaerodrome.com

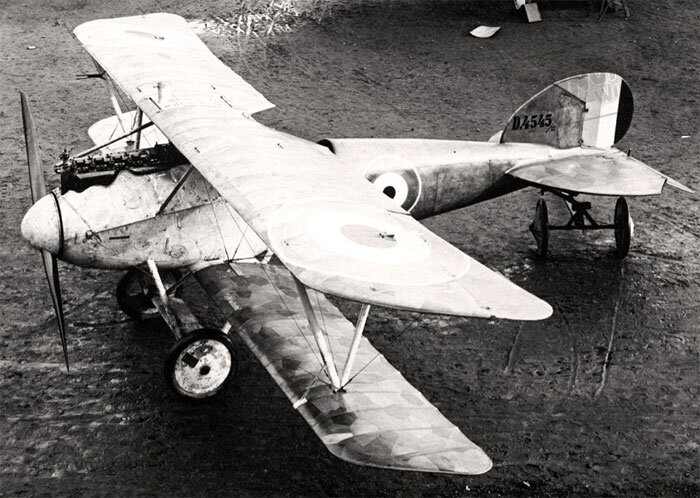

Another captured Albatros (D4545/17) in Royal Flying Corps markings including recovered rudder. This Albatros was brought down in December 1917 by anti-aircraft fire (which must have been relatively light as there is little damage evident). The pilot was Max Wackwitz of Jasta 24. The aircraft was then given an RFC capture number–G97.

Another angle on Albatros D4545/17 (the same aircraft as the previous photo) shows her original five-colour lozenge camouflage, so typical of many German flying machines of the First World War, and also her Royal Flying Corps roundels and fin flash.

A captured Fokker DVII (German serial 6792) is serviced with Sopwith Camels (in background), whilst wearing Royal Flying Corps markings. We can also see the standard multi-colour German lozenge camouflage paint scheme. A close look at the lettering on her sides, we see in addition to the 6792 serial, the words Fok DVII (Alb). This means it is a Fokker D7 and was manufactured under license by Albatros Werke. Photo supplied courtesy of John W. Adams Collection

Another captured Fokker DVII (D-7 serial number 2009/18), this time in French Air Force markings, carries long pitot tube on its starboard inter-plane struts, added post capture. Photo: theaerodrome.com

During the Second World War, there was no way an RAF fighter would share top billing next to a Hakenkreuze (Swastika), but this early application of a swastika in the First World War on a Pfalz D.III carries none of the evil we have come to know and is merely decoration with the roundel or cockade being painted over the mark that really mattered—the German Iron Cross which once occupied the fuselage. Swastikas were used by both sides during the First World War and were looked upon as good luck symbols. Some aircraft of the American squadron in the French Air Force, known as l’Escadrille Lafayette, actually carried a similar swastika. In fact, a swastika like this was the personal symbol of Raoul Lufbery, the leading ace of l’Escadrille Lafayette. Thanks to Mark Nelson for assistance with this aircraft identity. Photo: axis-and-allies-paintworks.com

A Fokker Eindecker EIII (the main production variant of the German fighter) captured and over-painted with early French Air Force cockades and tri-colour fin flash. The Fokker Eindecker fighters were a series of German First World War monoplane single-seat fighter aircraft designed by Dutch engineer Anthony Fokker. Developed in April 1915, the first Eindecker (“Monoplane”) was the first purpose-built German fighter aircraft and the first aircraft to be fitted with a synchronization gear, enabling the pilot to fire a machine gun through the arc of the propeller without striking the blades. The Eindecker granted the German Air Service a degree of air superiority from July 1915 until early 1916. This period was known as the “Fokker Scourge”, during which Allied aviators regarded their poorly armed aircraft as “Fokker Fodder”. Photo: axis-and-allies-paintworks.com

A Bristol F2BF2 Fighter (A7231) was captured by Jasta 5 of the German Air Force and provided valuable intelligence of the type’s capabilities. It was then painted in German markings and used as the squadron hack. Concerned that German Iron Crosses were not enough to deter German soldiers from taking pot shots at her, Jasta 5 pilots added large lettered notifications stating clearly: Don’t Shoot! Good People!

The Second World War

At the beginning of the Second World War, both for the Europeans and for the Americans (when their turn came two years later), the Allies were caught off guard by the ruthlessness, the seemingly unstoppable momentum and the new weapons of the enemy for which they had not yet found answering technologies. In Europe, the Fairey Battles, Hampdens, Lysanders, Whitleys, Gladiators and Ansons were simply not the equals of the Messerschmitts, Heinkels and Dorniers. The French, British, Dutch, and Belgians found themselves reeling backwards under the technological tsunami that was the blitzkrieg.

After Pearl Harbor, the scourge of the Mitsubishi Zero lashed the Pacific and South Asia from the Aleutians to Papua New Guinea and from Hawaii to Burma. The Hellcat and Corsair were still at least a year away from their debuts. If only the US Navy could get their hands on a single intact Mitsubishi Zero, not so they could copy or benefit from the technology, but so they could test fly it, understand its strengths and, more importantly, find its weaknesses. The Zero was fast, wickedly manoeuvrable and its pilots were battle tested in China and trained more rigorously than any in history. American and Allied pilots were just as courageous, but half a year into the Pacific war, they had not yet found the right tactics to fight the Zero on an equal basis. Then along came the Akutan Zero.

The Akutan Zero

In the summer following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, far, far out on the Aleutian Island archipelago, a young Japanese Petty Officer by the name of Tadayoshi Koga was fighting his rising fear and an overheating Nakajima 12-cylinder radial engine that was about to seize up on him. Just 15 minutes before, he had been strafing Yankee Catalina flying boats at the remote American fishing outpost of Dutch Harbor and just a few hours before that, he was drinking tea with his squadron mates aboard the mighty carrier Ryujo.

Over Dutch Harbor, he heard the metallic clank of something hitting his engine, perhaps a bullet or flak. Immediately, he smelled smoke and saw his oil pressure gauge start to drop. His oil line had been hit and he had just minutes to nurse his aircraft to safety. Trailing smoke, he made for a prearranged emergency landing spot on then-uninhabited Akutan Island, a remote, cold and mountainous island 25 miles further up the Aleutian chain from Dutch Harbor towards Unimak Island. There, if he landed safely, he would climb out of his fighter, destroy it and work his way to the coast where a Japanese submarine was standing by to rescue him. His section mates Chief Petty Officer Makoto Endo and Petty Officer Tsuguo Shikada stayed with him all the way and he could see them circling around him as he set up for his final landing in a grassy valley on a northeastern cape of Akutan. At the last minute, Shikada saw the sun glint off water hidden beneath the grassy surface of the valley. He knew instantly that Koga should have made a wheels up landing, but it was too late.

As soon as the aircraft’s weight was on them, Koga’s Zero’s wheels immediately dug into the boggy ground. From high above Shikada saw it flash in the sun as it dug in and snapped onto its back. The last thing that Koga saw was the flashing, tall, green grass, the mountains in the distance and the sun on the mists in the valley. His neck broke when the aircraft flipped onto him. Endo and Shikada were required to strafe and destroy the Zero to prevent it from falling into enemy hands, but could not bring themselves to do so as they were not sure whether Koga had survived and had just been knocked out.

He hung there in his straps until the heat left his body. He hung there while his mates landed back aboard Ryujo. He was still hanging there under his Zero more than a month later when Lieutenant Bill Thies’ PBY Catalina overflew the spot on his way into Dutch Harbor after being off course. He and his crew circled Koga’s aircraft with its bright red Hinomaru roundels on its wings and knew they had found something important.

Within just a few weeks, the Zero had been removed from Akutan to San Diego and in another month, it was ready to fly. While Koga’s body lay buried on an uninhabited island in a frozen corner of the world, his aircraft was flying in the sunny South Californian sunlight, its beautiful, serene and elegant Hinomarus replaced by the hated white stars on blue circles of the enemy.

The Akutan Zero was the first intact enemy aircraft to be acquired, repaired and flight evaluated by the newly formed Technical Air Intelligence Unit, whose job it was to recover Japanese aircraft to obtain data regarding their technical and tactical capabilities. The Akutan Zero became TAIU No.1. The tests immediately bore fruit. Lieutenant Commander Eddie R. Sanders took the Akutan Zero up for its first test flight and reported: “The very first flight exposed weaknesses of the Zero which Allied pilots could exploit with proper tactics... immediately apparent was the fact that the ailerons froze up at speeds above 200 knots so that rolling maneuvers at those speeds were slow and required much force on the control stick. It rolled to the left much easier than to the right. Also, its engine cut out under negative acceleration due to its float-type carburetor. We now had the answer for our pilots who were being outmaneuvered and unable to escape a pursuing Zero: Go into a vertical power dive, using negative acceleration if possible to open the range while the Zero’s engine was stopped by the acceleration. At about 200 knots, roll hard right before the Zero pilot could get his sights lined up.”

The Akutan Zero was just one of literally hundreds of aircraft that fell into the hands of the enemy on both sides during the Second World War, but it was the best known—at least after the war. By the start of the Second World War, the Germans and the British had special units formed and waiting for enemy aircraft to fall into their hands—the British had test facilities and units like 1426 Enemy Aircraft Flight (EAE), while the Germans had the Zirkus Rosarius and their test facility at Rechlin plus Special Operations units like Kampfgeschwader (KG) 200. The Japanese and the Americans both sought to acquire enemy aircraft for evaluation and the Germans and Japanese even used captured aircraft on operations—both clandestine and tactical.

While both sides had systems for retrieving captured aircraft and for testing them, ordinary field commanders and flying units would often mark captured aircraft for themselves and operate them as squadron instructional machines or as squadron hacks. The result was hundreds of captured aircraft usually used for the enjoyment of the pilots and as war trophy motivators.

Here, now, are some of the thousands of images we found and some of the stories of their capture and subsequent fates:

Japanese Navy fighter pilot Petty Officer Tadayoshi Koga’s Mitsubishi Zero would live on to fly again with the United States Navy, but sadly Koga’s body would be lost among hundreds of unknown Japanese servicemen who died in the Aleutian Islands campaigns. Photo: militaria.ee

The Japanese Imperial Navy carrier Ryujo delivered death and destruction to Catalina crews in Dutch Harbor, Alaska in July of 1942, but she also unwittingly delivered unprecedented intelligence to the US Navy in the form of a Mitsubishi A6M Zero, the first flyable enemy aircraft to fall into US hands. The Japanese Navy sent two carriers (Ryujo and Junyo) with 82 fighters and bombers, escorted by two heavy cruisers (Takao and Maya), and three destroyers. Also included in this task force were troopships holding 2,500 troops, 5 I-class submarines, and 1 oil tanker. This task force was to destroy Dutch Harbor, and occupy the islands of Attu, Kiska, and Adak. Photo: militaria.ee

4 June 1942, half a year into the havoc created by the Mitsubishi Zero throughout the Pacific Region, Petty Officer Tadayoshi Koga’s Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero takes a hit in an oil line over Dutch Harbor, Alaska. Koga was part of a three-plane section from the aircraft carrier Ryujo that had just shot down an American Consolidated PBY Catalina and was in the process of strafing the survivors when his Zero was hit. Photo: US National Archives

With Koga’s engine smoking and running out of oil, Koga and his two wing men reduced speed to preserve it for as long as possible and made their way to unpopulated Akutan Island, about 25 miles from Dutch Harbor. Akutan was a designated emergency landing area with a Japanese submarine patrolling nearby to rescue any downed pilot. Here, Koga made an attempt to land with his wheels down, but the grassy meadow was boggy and his gear dug in and flipped the Zero on its back. Koga was killed instantly, likely with a broken neck. His squadron mates were instructed to strafe and destroy any downed aircraft to save it from falling into enemy hands, but they were unsure whether their friend was dead or alive and were loath to kill him if he had survived. The crash site was undetected for a month, but was finally spotted by a PBY. A recovery team was sent immediately to inspect the aircraft wreckage and recover intelligence. Photo: Arthur W. Bauman, USN

An inspection crew clambers over Koga’s damaged Zero on Akutan Island. The smallest member of the team had the unpleasant task of climbing into the cockpit and cutting Koga’s harness. His body was dragged out and photographed then buried in a shallow grave nearby. An attempt was made in 1988 to recover Koga’s body and repatriate his remains. The grave was found empty. A search of records indicated that an American war graves team had dug up Koga and buried him as unidentified along with other Japanese bodies at Adak Island. This graveyard was excavated in 1953 and the remains of the 236 Japanese buried there were repatriated to Japan and Koga’s body would never be identified. After two attempts to recover the Zero without damaging it, it was finally removed upside down by barge to Dutch Harbor. Photo: Arthur W. Bauman, USN

Koga’s Mitsubishi, soon to be known as the Akutan Zero, is hoisted from a transport barge at Dutch Harbor and loaded into the USS St. Mihiel for transport to Seattle, Washington. From there, it was transported by another barge to NAS North Island near San Diego where repairs were made—straightening the vertical stabilizer, rudder, wing tips, flaps, and canopy. Photo: US National Archives

The captured A6M Zero fighter known as the Akutan Zero is seen landing at San Diego, California, United States, in September 1942. It carries the standard medium blue over light blue scheme typical of carrier-borne aircraft of the early war. Photo: US Navy

The Akutan Zero taxiing at San Diego’s NAS North Island. For a series of breathtaking photos of the Akutan Zero’s recovery and subsequent flights, visits Warbird Information Exchange (and sign up!) The photos, posted by member “rtwpsom2” are from NARA (National Archives and Records Administration of the United States), via Sean Hert and are EXCELLENT. Photo: US Navy

The Akutan Zero in flight, high above San Diego during initial flying tests. There are those that say it was the most important intelligence acquisition of the war and ultimately led to the defeat of the Japanese Army and Navy air forces. There are others who say that it was somewhat inconsequential, as fighter pilots in the Pacific area were already and quickly learning how to fight the nimble fighter. As well, the aircraft which would ultimately best the Japanese in the air were already in design and in production. Regardless of the impact, the Akutan Zero was a sensation, albeit a Top Secret one. Photo: US Navy

Koga’s crashed aircraft, while resurrected temporarily, did not in fact survive the war. Following its tests by the Navy in San Diego, the Zero was transferred from Naval Air Station North Island to Anacostia Naval Air Station in 1943 (becoming TAIC 1). In 1944, it was recalled to North Island for use as a training plane for rookie pilots being sent to the Pacific. As a training aircraft, the Akutan Zero was destroyed during an accident in February 1945 at North Island. While the Zero was taxiing for a takeoff, a Curtiss SB2C Helldiver lost control and rammed into it. The Helldiver’s propeller sliced the Zero into pieces. Only small bits (instruments) still exist in museums in Washington and Alaska. Photo: US Navy

One of the first Allied aircraft to be captured and put to work in Luftwaffe colours during the Second World War were the North American NA-57 and NA-64 trainers of France. The Armée de l’Air, the French Air Force, and the French Navy already had 230 NA-57s and had ordered 230 of the NA-64 Harvard predecessors, and 111 of the initial order (of NA-64s) were already in France when the Germans invaded. They gratefully took the excellent trainers (230 NA-57s and 111 NA-64s), while the other 119 still on order were delivered to Canada and used extensively in training RCAF and commonwealth pilots. The RCAF named them Yales. This camouflaged example of an NA-64 carries only the Balkenkreuz on its fuselage and did not have to endure the indignity of a Hakenkreuz (Swastika) on its tail. Photo: Luftwaffe

A Luftwaffe officer flies along with a disturbingly high angle of attack in this photo of a captured Armée de l’Air North American NA-57. The NA-57 can be identified by its ribbing and fabric covered fuselage. The peaked officer’s cap would most certainly have flown off at some time during the flight. My professional opinion is that this is a staged shot of one on the ground superimposed on a cloudscape. The angle is perfect for a sitting/parked Yale. Can’t be sure of this but I suspect it. The NA-57 is painted in the scheme common to the NA-57 and 64 trainers—overall bare metal with bright yellow engine cowling and tail.

In a scene so typical of a Canadian training base during the Second World War, an all-metal NA-64 (called North by the French and Yale by the RCAF) warms in the winter sun in Europe somewhere during the Second World War.

An NA-57 in Luftwaffe markings with yellow cowling and empennage, photographed at Guyancourt, France in early 1944. Image via alternathistory.org.ua/

A year and a half before the Americans were in the war, American-designed and -built aircraft like the previous French Norths (Yales) were not only in the war, but already captured and remarked as Luftwaffe. One of these types was the Curtiss Hawk Model 75 (P-36). The Germans captured several dozen of Armée de l’Air Curtiss H-75 Hawks during the French campaign in the summer of 1940. Many of those were subsequently donated (or sold) to Finland, later joined by Norwegian examples up to a total of 44. Others were operated by the Luftwaffe. A dozen of captured Curtiss Hawks were assigned to 7/JG 77 (The Aces of Hearts) during August–October 1940 as interim equipment while awaiting delivery of their Messerschmitt Bf 109s. After this, some were utilized in the fighter-trainer role with Jagdfliegerschule 4 near Nuremberg. Photo: Luftwaffe

There is no doubt that the Luftwaffe pilots of Jagdgeschwader 77 enjoyed the experience of flying the captured American-built French Curtiss Hawk 75s, and learning that they were no competition for the Luftwaffe’s Messerschmitt 109s, but enough was enough. They could not have enjoyed the time they were equipped with them when the rest of the Luftwaffe was wreaking havoc with the 109. Thankfully, it was an interim situation and their Hawks, along with KQ+ZA, were handed to Jagdfliegerschule 4 near Nuremberg as a fighter-trainer. Photo: Luftwaffe

One of the best-known and most photographed captured aircraft in enemy markings is the now-infamous Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress Wulfe Hound. This “Fort” was a B-17F of the 303 Bomb Group of the 8th Air Force that a made a forced landing in France in December 1942. Wulfe Hound became the first B-17 captured intact by the Luftwaffe and was thoroughly used by them to better assess weak points of the Flying Fortress. It was later transferred to the Luftwaffe’s KG 200. Wulfe Hound’s American pilot, Lieutenant Paul Flickenger, said that he always felt guilty because his was the first B-17 that the Luftwaffe was able to capture in a flyable condition. The crew was attempting to destroy the airplane by stuffing a parachute into a fuel tank and then firing a Very pistol flare into it. Unfortunately, the Germans arrived before they could get a fire started. He ended up as a POW and managed to escape twice, being captured again on both occasions. Photo: Luftwaffe

A shot of Fortress 124585, nicknamed Wulfe Hound by its original USAAC crew, shows the Swastika and Balkenkreuz markings of the Luftwaffe. All aircraft that were captured by the Germans had their original national markings removed and replaced by the Balkenkreuz and Swastika and then had their undersides painted overall “RLM 04 yellow” to help prevent trigger-happy anti-aircraft crews from destroying the aircraft and months of important intelligence work. Boeing B-17F-27-BO Fortress (c/n 3270/3324, USAAC Serial 41-24585) flew with the 360th Bombardment Squadron, 303rd BG. Wulfe Hound force-landed at Melun, France on 12 December 1942, after attacking the Rouen-Sotteville railroad marshalling yards, while in service with 303rd Bomb Group, at RAF Molesworth. After flight testing at Rechlin, the Luftwaffe’s famed test facility airfield, she visited fighter units throughout Germany and France so that pilots could recognize the Fortress’ strengths and weaknesses. Wulfe Hound then returned to Rechlin in July 1943, before being transferred to Kampfgeschwader (KG 200) in September 1943 and coded A3+AE. Profile via wingspalette

It’s likely that this Luftwaffe-marked B-17 Fortress is not Wulfe Hound, as the Swastika on the tail is considerably bigger than in other photographs of the famous aircraft. This Fort is heavily camouflaged from marauding Allied aircraft, and was used extensively by KG 200 for night missions. Kampfgeschwader 200 (Battle Wing 200) was a Luftwaffe unit of the Second World War. The unit was the Luftwaffe’s special operations wing that carried out long-distance reconnaissance flights, tested new aircraft designs (when a special Erprobungskommando unit was not used), and operated captured aircraft. This unit also operated a Short Sterling, P-38, Mosquito and a Beaufighter.

Hans-Werner Lerche, the legendary Luftwaffe test pilot from the Luftwaffe’s Rechlin test facility wrote about his experience with another B-17 in his Second World War memoir called “Luftwaffe Test Pilot–Flying captured Allied Aircraft of World War 2”. Lerche writes:

“The B-17 interested us so much because of its flying characteristics but more because of its supercharged engine, which gave excellent performance at higher altitudes. These superchargers were activated by exhaust-driven turbines which became really efficient corresponding to the greater difference in air pressure at higher altitudes, exactly when more power was needed. For that reason the Flying Fortress was primarily made available to the power plant experts, who tried to get to the bottom of as many details of the engines as possible. The most varied measuring instruments were installed for this purpose, so that the fuselage behind the bomb-bay was like a laboratory with engineers in attendance. I took over the following test flight, which was to take place with the full complement of the engineers aboard; our task was to monitor the engine and airframe performance in climbing to higher altitudes. I remember this flight particularly well, and shall therefore dwell on it some detail.

The take-off was made with full fuel tanks, which meant having some 2310 Imp gals of fuel on board. We departed from the concrete runway of Larz airfield and the take-off was monitored on instruments. Even with the comparatively heavy all-up weight the actual take-off presented no problem and the aircraft handled normally. Then began the climb with maximum climbing power which was also measured and monitored. Everything went very well at first. The engineers were busy doing their jobs, and we had meanwhile reached an altitude of at least 9000 ft, and we saw ourselves in a nice mess: the starboard outer (No.4) engine was on fire! It was quite a remarkable fireworks display with the flames flaring out just behind the engine nacelle and over the wing to a length of some 15 feet.

Now, what does one do when an engine is on fire? By no means throttle back the misbehaving engine, but instead stop the fuel flow immediately by shutting the relevant fuel valve so that the fuel already in the pipes and carburettor is used up as quickly as possible. That done, I alerted the rest of the crew and the engineers about the fire – in so far as they had not already noticed it themselves. For this purpose there was a loud alarm bell in the B-17, which could be heard everywhere despite the rumble of the engines. In any case, I also opened the bomb-bay doors as I considered this is the best method of bailing out from this aircraft without getting caught in the tail unit. The fuel in the pipes was soon used up, but I let the engine run for a while longer to make sure every last drop was gone. Despite this, the flames hardly became smaller at all.”

Lerche, who had flown the B-17 from Denmark where it had landed, had enough experience with the type to land it successfully in this situation. Photo via ww2incolor.com

If Allied crews were in the vicinity of Switzerland when they ran into mechanical problems, they chose to make forced landings in the neutral country, rather than risk capture and internment as POWs. They were however not allowed to return to the war and their aircraft were impounded. Switzerland played host to numerous crews (170 aircraft landed or crash-landed in Switzerland during the war—mostly B-17s and B-24s) and even commandeered some of their aircraft for evaluation. Here we see the strange sight of a strategic offensive bomber in the bright red markings of neutral Switzerland. This B-17G-35-BO (QJ-D, s/n 232073), operated by the 339th Bombardment Squadron, 96th Bomb Group, force-landed on 13 April 1944. It was returned to England in September 1945. Many of the aircraft were painted in the red Swiss markings simply for the ferry flight to a storage field at Dübendorf, Switzerland, not wishing to be inadvertently shot down.

Another B-17 in Luftwaffe markings. This one, the second B-17 to fall into German hands was B-17F-85-BO “Flak Dancer” (42-30048) from 544BS 384BG. The aircraft was piloted by Lieutenant Dalton Wheat when he forced-landed at Laon airfield in France on 26 June 1943, on a mission to Villacoublay. After repairs and traditional period of trials in Rechlin, the Flying Fortress was transferred to KG 200 in the spring of 1944 and coded A3+CE. Units like the famous KG 200 actually operated a number of captured B-17 bombers, in particular on night missions, where the markings were less obvious. Due to the lack of German aircraft with sufficient range, some recon missions used captured American B-17s or B-24s and Soviet Tu-2s. For the most part, these machines were used for re-supply roles (dropping in supplies to German forces operating behind Soviet lines), or transporting important personnel. It appears that this was photographed at a captured Luftwaffe airfield late in the war as the gawkers appear to be Allied airmen.

In the fast shifting battlefields of the North African campaign, where the whole desert was an emergency landing field, aircraft could in fact change hands more than once. Here we see Hawker Hurricane Mk I Trop* V7670, a former 260 Squadron Hurricane in the Desert Air Force. It had been captured by the Wermacht in April 1941, but was then taken back by the Allies in January of the following year at a place called Gambut in Libya, albeit in poorer condition. * The “Trop” was for “Tropicalized”—meaning fitted with modifications for the desert sand and heat. Photo: Luftwaffe

Former 261 Squadron Hawker Hurricane V7670 (from previous photograph) at the time of its recapture (January 1942), some eight months after the Germans took it. It clearly had seen better days. It was one of about 30 Hurricanes which were left in Derna, Bomba and Gazala. The Germans had made use of two of the Hurricanes—V7670 and T9536. Photo via Wikipedia

A Hawker Hurricane Mk 1 in Luftwaffe markings. Little is known by us about this captured aircraft. On the web, I have read where it was operated by Jagdgeschwader 51, but was unable to corroborate that. Photo: Luftwaffe

A rare colour photo of a Hurricane in the service of the Luftwaffe—with mechanics, pilot and brass looking on. Looking at this image and the previous black and white image, it seems possible that these are one and the same Hurri. Photo: Luftwaffe

This Spitfire (colour image is a model) suffers the double indignity of having not only Nazi markings, but the attachment of a Daimler-Benz DB605 Engine. The RAF identity of this aircraft was EN830—a Spitfire F.Vb (Merlin 45) and was the presentation aircraft called “CHISLEHURST AND SIDCUP” (a grammar school on Kent). The Spitfire force-landed on the occupied Channel Island of Jersey after air combat over Ouistreham, France on 18 November 1942. The pilot, Pilot Officer Scheidhauer was captured and made a POW. Scheidhauer took part in the Great Escape, but was recaptured at Saarbrucken, and shot dead by the Gestapo on 29 March 1944, along with 50 others who took part. After the Spitfire was captured and received its DB605, it was taken to Sindelfingen Daimler-Benz factory, near Echterdingen, where a 3.0 m. diameter Bf 109G propeller was added, together with the carburettor scoop from a Bf 109G. After a couple of weeks, and with a new yellow-painted nose, the Spitfire returned to Echterdingen. Capt Willy Ellenrieder, of Daimle-Benz, was the first to try the aircraft. He was stunned that the aircraft had much better visibility and handling on the ground than the Bf 109. It took off before he realized it and had an impressive climb rate, around 70 ft. (21 m.) per second. Much of the Spitfire’s better handling could be attributed to its lower wing loading. Inset photo via Stewart Callan, Flickr . Model and its photo by Alain Gadbois

After a brief period at Rechlin confirming the performance data, the modified Spitfire (CJ+ZY) returned to Echterdingen (today’s Stuttgart Airport) to serve officially as a test bed. It was popular with the pilots in and out of working hours. Its career ended on 14 August 1944, when a formation of US bombers attacked Echterdingen, wrecking two Ju 52s, three Bf 109Gs, a Bf 109H V1, an FW 190 V16, an Me 410 and the Spitfire. The remains of the hybrid Spitfire were scrapped at the Klemm factory at Böblingen. Text via Stewart Callan, Flickr

Achtung Spitfire! One wonders why the Luftwaffe wanted to re-engine the Spitfire with a Daimler-Benz engine from a Messerschmitt Bf 110; it’s not like Supermarine would build the result for them. Perhaps the Merlin was permanently destroyed and they had not captured any other Rolls-Royce engines. Photo: Luftwaffe

At first glance, I saw a P-47 in this photo, but then on second glance realized it was not... it took me a while to figure it out, as I was not familiar with French types. This is the only Marcel Bloch MB 157 (conversion of a MB 152 meant to have a 1,580hp Gnome-Rhône 14R-4 engine) ever built. It was taken by the Luftwaffe for evaluation. After a series of very promising test flights, the aircraft was flown to Paris-Orly, where the Germans removed the engine (it was a slightly less powerful one) and brought it to the Gnome-Rhône factory at Bois-Colombes. The aircraft remained in an incomplete state in Orly, until it was destroyed in an Allied air raid. During the research phase under German control, it wore the German registration code PG+IC. Photo: warbirdsforum.com

The Marauder that never marauded. A Martin B-26B Marauder (41-17790) of the 437th Bomb Squadron of the 319th Bomb Group, USAAF in Luftwaffe markings. This Marauder was evaluated by the Luftwaffe in 1943 and then displayed at an air show in Germany after its bizarre capture on 2 October 1942. The aircraft never saw combat, having been lured to a Dutch island following spurious German radio signals as it was trying to land somewhere safely (following an engine fire) on its remaining engine during its delivery flight from Iceland to Scotland. Flown by 2nd Lieutenant Clarence Wall, the crippled bomber force-landed on a beach in Noord Beveland, Netherlands. Photo: Luftwaffe

This is exactly how most of the aircraft that fall into enemy hands are retrieved. Marauder 41-17790 (the one from the previous photo) sits forlornly on a beach on the Dutch island of Noord Beveland, surrounded by admiring Germans. The pilot, Clarence Wall, was lured off course by fake radio directions from Germans and, having an engine fire, made a picture perfect wheels up landing. The aircraft was quickly jacked up and removed. Hans-Werner Lerche, the legendary Luftwaffe test pilot from Rechlin wrote about his experience with this aircraft in his Second World War memoir called “Luftwaffe Test Pilot–Flying captured Allied Aircraft of World War 2”. He said, “A mid-wing monoplane with an aerodynamically faultless fuselage, the aircraft had a fast and racy look about it even from the outside. Its long range also made it suitable for direct ferry flights across the Atlantic. But the B-26 had its negative points. With its small wing area and a gross weight of some 30,000 lb (later increased to over 38,000 lb), the load per square foot of the wing area was relatively high, and the high take-off and landing speeds caused so many bad accidents that this aircraft at first had a poor reputation amongst the crews and was known as the ‘Widow Maker.’ Its other nickname of the ‘Flying Prostitute’ was unknown to me when I became intimate with the Marauder for the first time. Apart from other bad characteristics, malicious tongues also asserted that the Marauder’s landing speed was higher than its cruising speed. Yet all this did not prevent experienced crews from appreciating the combat values of the B-26 on account of its high speed and strong armament, and using it accordingly. That much was known to us – and it was to be expected that the grass field at Rechlin would not be abundant enough for this ‘hot’ aircraft.” Photo: Luftwaffe

It is surprising that any of the aircraft captured by both Germany and Japan survived the war. Here, an RAF ground crew inspects the former USAAF B-26B Marauder (41-17790) that carried the Nazi markings for nearly two and a half years. The bright yellow fuselage band and tail flashes can still be seen (though barely visible on orthographic film), but the Swastika has been blanked out by a censor in this photo. We can also see the paint circle where the old USAAF star roundel was painted over—just to the right of the airman. Photo: RAF

A Vickers Wellington Mk I captured by the Luftwaffe from the Royal Air Force’s 311 Sqn (KX-T, RAF Serial L7842). 311 Squadron was first formed at RAF Honington, Suffolk on 29 July 1940, equipped with Wellington I bombers and crewed mostly by Czechoslovakian aircrew who had escaped from Europe. This was before the aircraft received its traditional yellow underside paint used by the Luftwaffe’s Rechlin test facility. L7842 was delivered in mid-1940. It was lost on 6 February 1941 while in service with No. 311 (Czech) Squadron, RAF, while on a mission to Boulogne (France). It was forced to land and captured intact. Photo: Luftwaffe

A wonderful digital recreation of the captured 311 (Czechoslovak) Squadron Vickers Wellington shows us just how she was repainted. Luftwaffe markings were added including painting her underside yellow as both the Axis and the Allies did with experimental aircraft. She still carries her 311 Squadron code letters (KX-T) and her RAF serial (L7842). The crew was comprised of P/O F. Cigos, Sgt P. Uraba, P/O E. Busina, F/L Ernst Valenta, Sgt. G. Kopal and P/O K. Krizek. All were made Prisoners of War, with Valenta eventually being murdered by the Gestapo following an escape attempt at Sagen POW Camp. Image via airwarfare.com by Checkmysix

I searched for days on the web trying to find an image of the one and only Avro Lancaster to be captured and taken to Rechlin for study and eventually for missions. It is mentioned in Hans-Werner Lerche’s book, but there is no photographic proof to be found. The leading candidate for its RAF identity is Lancaster ND396, BQ-D, of 550 Squadron, which crash-landed near Berlin on 30–31 January 1944. Late in the war, it behooved the Germans to get the intact aircraft to Rechlin as soon as possible, for marauding Allied aircraft would soon be on hand to make sure it would never fly for the Nazis. Here we see another Lanc being shot up by a P-51 the day after it went down in a field in Germany. Note the staff car which then got the same treatment. The strafed Lancaster, probably PB362 of 83 Squadron, crash-landed near Rouen shortly after midday on 18 August 1944. Photo: ww2aircraft.net

Even the Finnish were into capture and release. This Soviet lend-leased P-40M (USAF 43-5925) was captured by the Finns during the Battle of Leningrad. Piloted by Soviet pilot, Sub. Lt. V.A. Ruevin from 191st fighter squadron, on 27 December 1943, it made a forced landing on the frozen surface of Lake Valkjarvi, Karelian Isthmus. The Finns captured it in perfect condition. It was overhauled at the Mechanics’ School and delivered to HLeLv32 on 2 July 1944. It was used till 12 February 1945. It was not used in combat flights however, due to lack of manuals and parts. The two letters “KH” on the fuselage possibly stood for the Finnish words “Koe Hävittäjä” (Test Fighter) or even Kittyhawk. The Finns also employed a swastika device as a national marking, but it was blue on a white roundel and was 45º off the alignment of the Nazi version. The Finnish Swastika predates the Nazi symbol by a number of years, dating back to the end of the First World War. The Latvians also use a swastika (red on white). Photo via WWII in Color

A Ju 88 photographed in Foggia, Italy, in 1943, when its Romanian pilot defected to the Allies in Cyprus. It was repaired by the men of the 86th Fighter Squadron and flown from Italy to Wright Field in 1944 by 86th Fighter Squadron Comanche pilots Major Fred Borsodi (the guy with the big smile) and Lt Pete Bedford. This Junkers Ju 88 not only wears USAAF markings, it wears a fighter squadron’s nose art. It appeared in war bond drives, and was finally returned to Wright Field in the summer of 1945 after being superficially damaged in Los Angeles. It finally went to Freeman Army Air Field, Indiana and was eventually scrapped. Photo: USAAF

The same Junkers Ju 88 from the previous photo is shown being prepared for flight at Foggia, Italy wearing USAAF star roundels, RAF fin flash and Luftwaffe camouflage. When it landed back at Freeman and Wright Fields it was repainted in Nazi markings for public viewing. Photo: USAAF

A Heinkel He 111H bomber, which was abandoned by the Luftwaffe during the retreat after the Battle of El Alamein on a landing ground in Libya after being “commandeered” by No. 260 Squadron RAF. Several 260 Squadron pilots climbed in and took off to check it out. It worked fine, so they painted RAF roundels on it and the squadron letters “HS-?”, flying it to Alexandria for mess supplies. 260 Squadron’s popularity climbed fast in this period as they were the only mess around with cold beer in a hot desert. It was nicknamed Delta Lily. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Junkers Ju 52/3m – 450 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force. This Luftwaffe Junkers Ju 52/3m transport aircraft was captured intact by Australian forces at Ain-El Gazala, Libya, repainted with the Royal Australian Air Force’s roundels and nicknamed “Libyan Clipper”. The aircraft was used by 450 Squadron RAAF to transport mail, food supplies and small items from Cairo and back to the front line, doing two or three trips each week. Lord Casey, Governor General of Australia, came in this aircraft to see the men of the squadron in 1943. Photo: Australian War Memorial via adf-gallery.com.au

The starboard side of the Libyan Clipper had a different layout for her lettering. The Junkers Ju 52 was built in very large numbers—nearly 5,000. Their Luftwaffe crews lovingly referred to them as Tante Ju (Aunt Ju). Photo: Australian War Memorial via adf-gallery.com.au

One of the most beautiful aircraft of the war was the Italian-designed SM.82 Trimotor. In my estimation it belongs in the top ten most beautifully designed aircraft of the war along with the Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 (next photo). The Savoia-Marchetti SM.82 Canguru (Kangaroo) was an Italian bomber and transport aircraft of the Second World War. It was a cantilever, mid-wing monoplane trimotor with a retractable tail wheel undercarriage. About 400 were built, the first entering service in 1940. Although able to operate as a bomber with a maximum bomb load of up to 8,818 lb (4000 kg), the SM.82 saw very limited use in this role. After the armistice with Italy in September 1943, the Germans captured 200 SM.82s, many being operated as transports by the Luftwaffe. The Germans were thus rewarded for the delays in their order for 100 SM.82s, only 35 of which were delivered in 1943. These aircraft had better capabilities as transports than the Ju 52, the standard transport aircraft of the Luftwaffe, even if it was much more robust, being all metal. The “Savoia Gruppen” operated many of these aircraft, with a force in early 1944 of over 230 aircraft, but little is recorded of the activities of these aircraft in the last 18 months of the war as most were ad-hoc units. Records were either not kept or were destroyed. Information via Wikipedia, photo via ww2aircraft.net

There is something about a trimotor that seems just right and balanced and yet which seems so foreign. Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero (Sparrowhawk) is one of the most compelling designs extant with striking lines and art deco styling. After the Armistice in September 1943, the Luftwaffe captured a number of the beautiful aircraft and pressed them into service. Photo via ww2aircraft.net

When the Italians surrendered on 8 September 1943, this was not the end of the combat history of the SM.79. A new Sparviero variant was designed and put into production, the SM.79-III torpedo-bomber. The North of Italy was still in German hands and a fascist government continued construction. Some Sparvieros were taken on the spot by the Luftwaffe and used with German or Italian crews as regular Luftwaffe utility transports. Some served in the newly created ARSI, the Air Arm of the Repubblica Sociale Italiana, which continued to fight on the side of the Axis. A few found their way to the Allied side and served with the Co-Belligerent Air Force against German Forces. The Co-Belligerent Air Force (Aviazione Cobelligerante Italiana, or ACI) dropped the use of the fascist symbol and, instead, employed the old First World War tri-colour roundel, the same used by the Italian Air Force today. Photo: wwiiaircraftphotos.com

A captured Gloster Gladiator (Luftwaffe serial NJ+BO) in the Russian forests—one of 15 Latvian Gladiators which were captured and used first by the Soviets, then captured by the Germans. When the Germans removed the Soviet red star markings they found the Latvian Swastikas underneath. The Germans operated them at virtual squadron strength as glider tugs for assault glider pilot trainees. None are known to have survived. Photo: FleetAirArmArchive.net

An RAF-marked Messerschmitt Bf 109 at Treviso Airfield, Italy, in March 1946. This aircraft, a former Croatian operated 109, was captured by the British and operated by 318 Polish Squadron in Italy immediately after the war. Note the Polish checkerboard symbol on the nose. The “LW” lettering was the RAF Squadron code for 318 Squadron. 318 was at Treviso for only one week in the month of May 1945, and then March to August of 1946. Photo: RAF

A Messerschmitt Bf 109G-2 “Gustav” code-named Black 14 and with the name “Irmgard” painted in Germanic lettering on the side (so-named after the German crew-chief’s girlfriend) was captured by airmen of the 79th Fighter Group. Here we see it shortly after the Americans painted their brand on her sides. During the Second World War, the 79th and its subordinate fighter squadrons were assigned to the 12th Air Force in the Mediterranean Theatre. With the beginning of the occupation period, the Group was reassigned to the Ninth Air Force which had been assigned the primary Army Air Corps occupation duties in the European Theatre. Photo: USAAF

“Irmgard”, the Messerschmitt Bf 109 captured by the 79th Fighter Group of the USAAF, is seen wearing the 87th Fighter Squadron crest, with an 86th Fighter Squadron P-40 Warhawk (X5-8) behind it. The 86th and the 87th along with the 85th Fighter Squadron made up the three squadrons of the 79th Group. Photo: USAAF

A great colour shot of “Irmgard” taken in the field with 87th Fighter Squadron emblems on each side. This appears to have been painted right over the dirt from the exhaust or perhaps the stain was cleaned off for the photo. This was applied to both sides. This emblem was eventually replaced by that of the 86th Fighter Squadron, shown in the next photo. Photo: USAAF

“Irmgard” eventually wound up at Wright Field in Ohio for testing. She is photographed here undergoing static testing. Note the replacement port wing. The original port wing can be seen off to the side, behind the tail. Here she has had her 87th Fighter Squadron emblem (a cartoon mosquito with a machine gun) replaced with that of sister 86th Fighter Squadron, a Native American with a Tomahawk and quiver of arrows leaning down from the clouds. Photo: USAAF

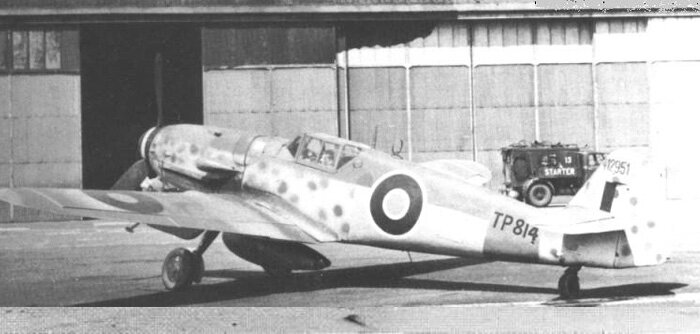

A Yank named Gustav—a captured Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 (Tropicalized) in USAAF colours. This intact fighter was captured by American soldiers on 8 May 1943 at Soliman airfield in Tunisia. Originally it belonged to the 4. Staffel of JG 77. The aircraft was disassembled, shipped to the USA, reassembled by the North American Aircraft company, and subsequently flown to Wright Airfield. Note the tropical filter, the re-painted surfaces and the missing seat armour. Photo: USAAF

Another shot of the USAAF’s Messerschmitt at Wright Patterson. The USAAF test pilot who evaluated the Yankee Gustav, Major Fred Borsodi, had this to say about the Nazi fighter: “The airplane was assembled by North American Aircraft and was flown briefly at the factory before being ferried to Wright Field by the undersigned pilot. The only changes made at North American were installation of American radio and oxygen equipment. The armour plate behind the pilot`s head was removed. The ME 109G has a high rate of climb and good level flight performance. Its range is very limited as only 105 gallons can be carried internally and flights of over 300 miles leave little gasoline for reserve... It is very light on all controls below 400 KPH but the turning radius is poor compared to our fighters. At high speed the controls become very heavy. The airplane is stable and should be a good gun platform but the vision is very poor under all conditions. The cockpit is cramped but would not be too bad if the visibility were better.” Photo: USAAF

A captured Messerschmitt Bf 109F with tropical filter on its engine cowl was used by No. 5 Squadron of the South African Air Force as a squadron hack. Here we see one of many times that the aircraft letter code was replaced by a punctuation mark. Photo: RAF

Another Messerschmitt Bf 109F, captured by a South African Air Force unit (No. 4 Squadron SAAF) in North Africa (with the serial “KJ-?”), is pictured on the airfield at Martuba’s No.4 Landing Ground in Libya, January 1943. It is not uncommon, for squadrons operating captured aircraft, to give them squadron markings so as to lay claim to the booty. Also it was common to give them a question mark (?) or an exclamation point (!) instead of an aircraft letter code. Whether this was done for humorous reasons or to keep letters for operational aircraft is not known. Martuba is where Stocky Edwards gained his first nickname—“The Hawk of Martuba”—when it was still in German hands. Today, Martuba is still a Libyan Air Force base. Photo: SAAF

In the previous photograph we make mention of Wing Commander James “Stocky” Edwards, Canada’s highest scoring living ace of the Second World War (as of the publishing of this article—January 2014). Stocky (then nicknamed “Eddie”) gained most of his victories while flying with 260 Squadron of the RAF’s Desert Air Force in North Africa. Here we see a captured Bf 109 (likely from the Luftwaffe unit III/JG77) in 260 Squadron code (HS) and an exclamation point as its aircraft designator. The aircraft was flown for evaluation purposes by squadron pilots including Stocky Edwards. This very Luftwaffe fighter may have met Edwards in aerial combat previous to its capture. Photo: RAF

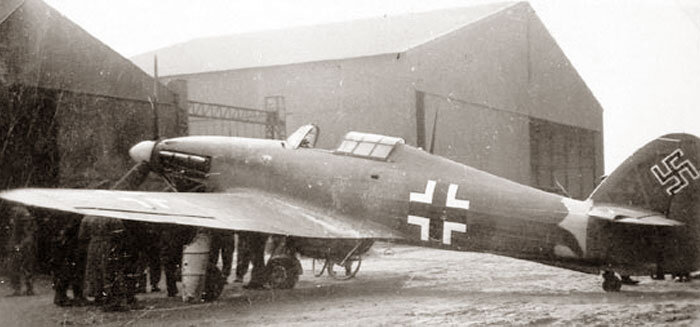

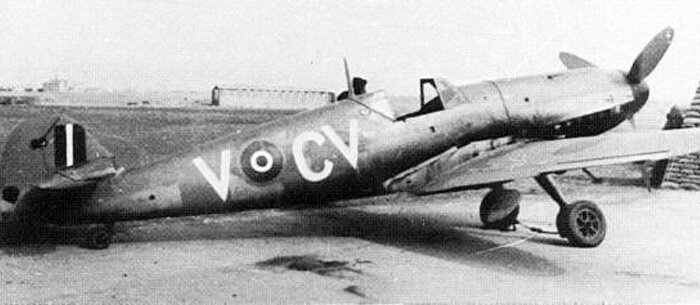

A Messerschmitt Bf 109G-2 “Black 6” (Trop), flown by Lt. Heinz Lüdemann, was damaged on 4 November 1942 as a result of a dogfight between fighters from 8./JG77 and Kittyhawks from 112 Squadron, RAF. Lüdemann made a perfect forced landing at the Quotafiyas airfield near Gambut in Libya. It was subsequently ferried to Gambut by another pilot. The Messerschmitt was found at the Gambut Main airfield by Australian Ken McRae of 239 RAF Wing. The aircraft was repaired by maintenance crews of the No. 3 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force and coded with their code—CV-V. Photo: RAF

Once the Messerschmitt Bf 109G from the previous photo was repaired, it was given the markings of No. 3 Squadron RAAF and the aircraft code letter “V” for Victory. This was Squadron Leader R. Gibbes’ personal code. No. 3 Squadron Engineering Officer Flight Lieutenant Ken McRae relates the story of finding the perfectly intact fighter:

“During the successful advance of November 1942 in the Western Desert, the Wing was returning to Gambut Satellite airfield, where we had operated from prior to the retreat. My co-driver and myself were ahead of the convoy and when we had arrived at our Satellite, the only aircraft there was a 3 Sqn. Kittyhawk on jacks. It had been under repair when we retreated six months earlier, as our orders were not to destroy aircraft that couldn’t be flown out as we’d probably be returning within a few days. The aircraft appeared to be OK and it was obvious no enemy had operated from the airfield. Our main object was to find an enemy aircraft that could be flown by our C.O. Bobby Gibbes – so we went to see if there were abandoned aircraft at Gambut Main, several miles away.

There were lots of damaged aircraft and we were delighted to find an almost-new 109. On examination the damage was slight – mainly no canopy – which must have been jettisoned in flight for the tail plane was damaged where hit by the canopy. I wrote CV on the fuselage and then realised if we left it unguarded someone else would grab it. I sent Rex back to the Squadron to notify Bobby of what had happened and saying we would return the following morning. A team of airmen and a truck was organised to come to Gambut Main early next morning.

In the meantime, three army officers appeared and wanted to know what I was doing with the 109. I told them that I was taking it back to the Squadron for the C.O. to fly and evaluate its capabilities. They informed me that they were Intelligence and I couldn’t take it – they wanted to evaluate it. I told them ‘no way’. – I had the aircraft and was going to keep it!

Outranked (I was a Flying Officer) and outnumbered, I did well to convince them the prize was going to 3 Sqn.

We finally compromised… they’d take the name plates from various places on the aircraft – which would allow them to find out where the bits and pieces had been manufactured. On departing their final remark was, “We’ll get it anyway.”

“Maybe,” I said, “but not before we’ve flown it.”

When Sergeant Palmer returned we parked the vehicle against the fuselage and that night slept under the mainplane. No one was going to get the 109, which we now knew to be a 109G.

The ground staff arrived early the next morning and the aircraft was towed back to the Sqn. I imagined the look in the eyes of the C.O. – to see such a prize and in such good condition.

Three or four days later the aircraft was repaired and the C.O. test-flew it and later made more flights.

Eventually the Intelligence people did get the aircraft and Bobby Gibbes flew it back to the Delta area. (Much later we heard that they had pranged it!)”

Captured in Tunisia in 1943 and often attributed to Heinz Lüdemann of 2./JG77, “Black 6” is likely one of the most famous, if not THE most famous 109 survivor extant thanks to her intricate restoration at the hands of Russ Snadden and his team. She appeared at numerous air shows throughout the early 1990s, demonstrating the grace and power of this beautiful aircraft and, in a twist of sheer irony, she was heavily damaged when landing from what was to be her final flight before permanent retirement in the RAF Museum. Her full history can be read here.

The end result of the previous description of stealing a Messerschmitt Bf 109 is one happy unit commander. Here Squadron Leader Bobby Gibbes smiles widely in “his” new Messerschmitt—the captured “Black 6” with an improvised canopy replacement. Photo via Mike Mirkovic at adf-gallery.com.au

Captured Messerschmitts of the South African Air Force.

Thanks to South African-born Yuri Maree, we have these two captured 109s from the North African campaign.

When No.1 Squadron arrived at Derna on Christmas eve 1941, the aerodrome was a sea of mud and heavy rain which curtailed most flying for several weeks. The squadron personnel amused themselves by inspecting the many abandoned German and Italian aircraft on the field. A Me 109F that had been shot up and crashlanded became the Squadron Engineering officer, 2/Lt ‘Red’ Connor’s pet project. Despite badly damaged wings, undercarriage and prop and a stripped instrument panel, he was determined to make it airworthy again. Various parts were scrounged off wrecks at Derna and nearby airfields, and a new airscrew was found at an airfield 100 km away. On the 18th January the 109 was started up for the first time, and just before noon on the 24th the CO Major Malcolm Osler flew it for ten minutes. General Rommel had started an offensive the day before, and an hour later the squadron’s ground party started moving further east to an airfield named Gazala No.3. The squadron’s Hurricanes, and Major Osler in the 109 flew to Gazala no.3 on the 26th. Two days later Captain Peter Venter, one of the flight commanders, flew the 109 for 30 minutes and reported reaching 700 km/h in a shallow dive. As soon as word got out that 1 Squadron had an airworthy Me 109F – the first one captured in the desert – RAF HQ in Cairo decided they wanted it. A signal was sent on the 25th with orders that it be flown to Heliopolis. Rommel’s offensive was gathering steam, and on the morning of 3rd February Major Osler departed Gazala no.3 for Heliopolis in the 109, escorted by a Hurricane. Later in the day the squadron moved further east to El Adem airfield. From Heliopolis the 109F was eventually shipped to England for further testing. Photo via Yuri Maree

Major Peter Metelerkamp at left, standing by "his" Me 109F. Photo via Yuri Maree

Major Peter Metelerkamp's “own” 109F. No.1 Squadron, still flying obsolete Hurricane Mk.2’s from LG 172 which was only 60 km behind the front, was in the thick of the fighting during the Battle of El Alamein that started on 23 October, 1942. 8TH Army broke through the Axis lines on 4 November and on the same day the SAAF’s first Spitfire Mk.V’s arrived at 1 Squadron. The unit was taken off operations for ten days to train on the aircraft and stayed behind at LG (Landing Ground) 172 as the Allied offensive moved west at high speed after the Alamein breakout. The swift German retreat left much equipment behind. On the 8th, the CO, Major Peter Metelerkamp and Engineering Officer Lt. ‘Red’ Connor and two mechanics drove to the abandoned German LG’s west of Daba, looking for flyable aircraft. They reported 120+ abandoned German aircraft, including about 90 Me 109s, numerous Ju 87 Stukas, a few He 111s, Ju 88s and twin-boom 20 seat gliders on LGs 20, 21 and 104. On LG 104 they found an intact Me 109F and after an inspection and service, Major Metelerkamp flew it back to LG 172 on 10 November. After a few low passes he made a “ropy landing” and the 109 groundlooped when the left brake locked up. Damage was slight, and after a new engine was installed Major Metelerkamp flew the 109 (renumbered AX-? and carrying 1 Squadron’s trademark red wingtips, visible in the first photo) in mock dogfights against the squadron’s new Spitfires on the 15th. He noted in his logbook that it couldn’t outturn the Spitfire but could outclimb it, and that downward visibility was poor. Captain Hannes Faure, one of the flight commanders, flew AX-? that afternoon and expressed the same opinion. The next day Lt. Stewart ‘Bomb’ Finney flew the 109, and on the 17th the squadron moved forward from LG 172 to resume operations. 8th Army’s advance was swift and No. 1 Squadron moved forward 830 km in big leaps: LG 172 to Martuba in Libya on the 19th where it joined the Spitfire Mk.V equipped 244 Wing, on to Msus and finally to El Hasseiat, south of Benghazi. ‘Bomb’ Finney ferried the Me 109 to Msus, from where Peter Metelerkamp flew it to El Hasseiat on 1st December. On the 6th the squadron was ordered to send the 109 back to 59 Repair and Salvage Unit at Gazala, when RAF HQ decided that tame 109’s caused confusion among AA gunners and wasted valuable fuel. Major Metelerkamp flew it back to Gazala, but most of the LG’s in the area were flooded by heavy rain and he landed at Tmimi where the SAAF’s (non-operational) Liaison Officer wanted to have a go at the 109. However, the cockpit hood had blown off upon landing at Tmimi and it was fixed by No.12 Squadron SAAF, based there. On the morning of the 8th Major Metelerkamp made a third attempt to reach Gazala but the 109’s engine failed on takeoff and, as he recorded in his logbook, “pranged her....thank God, before Colonel P--- took her off”. Major Metelerkamp was killed in action five days later. Photos via Yuro Maree

The fast-moving armoured war of the Eastern Front would from time to time cough up an intact enemy aircraft for both sides. Here we see a fur-hatted Soviet pilot or technician in the cockpit of Bf 109G-2/R-6 (No. 13903), in January of 1943. One can only imagine how cold this scene would have been in that brutal winter war. The date indicates that the German forces were just a few weeks away from surrendering at Stalingrad. Captured near Stalingrad and tested in the Soviet Union using the designation “Five-Pointer”, this fighter seriously worried the Red Army Air Forces leadership due to its excellent flight capabilities. Photo via forum.il2sturmovik.com

Another Messerschmitt Bf 109 trophy (14513 operated by II JG 3) bagged by the Soviets was tested against a Lavochkin La-5FN and Yakovlev Yak-9D, with the conclusion being that the Russian fighters could compete successfully against the 109. This aircraft was tested at NII VVS Research Centre after it had been captured, following a forced landing with battle damage. According to trophy lists, the Soviets would acquire 54 Messerschmitt Bf 109s with eight of these being fully operational. Photo via Stewart Callan, Flickr

Out in the North African desert, mechanics and pilots of the Royal Australian Air Force get a very close look at a captured Messerschmitt Bf 109F-4 with RAF serial number HK849. Used by 3 Squadron RAAF as a squadron hack. Photo via Lou Kemp

This Japanese Messerschmitt Bf 109 is certainly not a captured aircraft, but more of a military exchange project. Japanese 109 pilots pose with one of five 109 “Emils” sent to Japan. In 1941, the five Bf 109Es were sent to Japan, without guns and armament, for evaluation. While in Japan they received the standard Japanese Hinomarus (red meatball) and yellow wing leading edges, as well as white numerals on the rudder. A red band outlined in white is around the rear fuselage. Study of the Bf 109 in Japan led to the design of the formidable Kawasaki Ki-61 Hein (Japanese for “Swallow” or “Tony” as it was called by the Allies). Photo via dieselpunks.org

In 1943, the Japanese Army received one Focke–Wulf Fw 190A-5, and this aircraft was extensively tested during that year. It was most probably delivered by submarine, and also carried standard Luftwaffe camouflage, and was flown in Japanese markings. Photo via wwiivehicles.com

A strange aircraft with a strange roundel. This former Regia Aeronautica Macchi MC.200 “Saetta” was captured on Sicily in September 1943 and flown by pilots of the Desert Air Force of the RAF in North Africa. The Saetta was a Second World War fighter aircraft built by Aeronautica Macchi in Italy, and used in various forms throughout the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Air Force). The MC.200 had excellent manoeuvrability and general flying characteristics left little to be desired. Stability in a high-speed dive was exceptional, but it was underpowered and under-armed for a modern fighter. In keeping with a test aircraft, the rudder and fuselage band of this aircraft were painted bright yellow, while the roundel is wrong in every respect—proportion and size. Photo via 57thfightergroup.org

The Royal Air Force impounded four Messerschmitt Bf 108 Taifuns on the outbreak of the Second World War and put them into service, designating them as the “Messerschmitt Aldon”. One of them was used by the German Embassy and was at Croyden. That particular Taifun was blocked from escaping by the placement of a large woodden packing crate at the doors of the Embassy hangar. Another of the impounded 108s belonged to the Messerschmitt dealer/agent. This Taifun was first used by the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough in connection with the tests carried out there on the Bf 109E. The aircraft was pressed into service with the RAF on 17 April 1941 and received the RAF serial DK280. It was allocated to the Maintenance Command Communication Squadron (MCCS) at Andover. It was the fastest light communications aircraft the RAF had then, but they were often mistaken for Bf 109s. Postwar, 15 more captured Bf 108s flew in RAF colours. Photo: RAF

Royal Air Force Air Vice-Marshal Harry Broadhurst, Air Officer Commanding the Desert Air Force, about to board his Fieseler Fi 156 C Storch at the Advanced Headquarters of the DAF at Lucera, Italy. Broadhurst acquired the captured German communications aircraft in North Africa, had it painted in British markings and used it for touring the units under his command. Broadhurst took command of the DAF in January 1943, becoming (at the age of 38) the youngest Air Vice-Marshal in the Royal Air Force. He continued flying the Storch while commanding the 2nd Tactical Air Force in North-West Europe. Photo: RAF via Imperial War Museum

A captured German Fieseler Fi 156 C-3/Trop Storch (ex “NM+ZS”) commandeered by the Air Officer Commanding, Western Desert, Air Vice-Marshal Arthur Coningham, as his personal communications aircraft. A very crude roundel has been applied to cover the full fuselage Balkenkreuz. The photograph was probably taken at Air Headquarters, Ma’aten Bagush, Egypt. Photo: Imperial War Museum

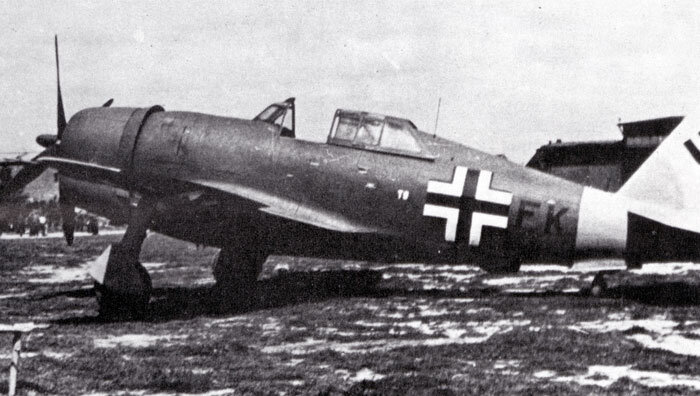

Focke–Wulf Fw 190G-3 (No. 160057) was one of two captured by ground crews of the 85th Fighter Squadron, 79th Fighter Group at Gerbini Airfield on the Island of Sicily, in September 1943. It was painted in a striking white scheme with red spinner, cowling, fuselage band and USN striped tail. Here we see it at Gerbini, covered in camouflage netting to keep it hidden from marauding Luftwaffe aircraft bent on destroying it to keep it from the Americans. Later, in 1945 while stateside, this aircraft was repainted in a standard USN 3 tone non-specular, intermediate blue and insignia white scheme. Photo: USAAF

The Gerbini Focke–Wulf Fw 190 (previous photo), flying unmolested above the United States. It was shipped to the United States in January 1944, where repairs were made. It was test flown at NAS Anacostia, then moved to NAS Patuxent River in February. It should be noted that the USN seemed impressed enough by this aircraft that they encouraged development of the F8F Bearcat, which was clearly and visually inspired by the tough fighter. Photo: US Navy

The other Focke–Wulf Fw 190A that was captured at Gerbini and then flown by the 85th Fighter Squadron, 79th Fighter Group of 12th Air Force. The 79th FG is the same unit that captured and flew the Messerschmitt Bf 109 Irmgard, shown earlier in this article. To avoid any possibility of the aircraft being taken to be the enemy, the aircraft was painted overall red with yellow wings and red wingtips as well as a yellow fuselage band and horizontal stabilizer. It carries USAAF markings as well as the flying skull emblem of the 85th FS. Photo: USAAF

It is believed that this is an air-to-air photograph of the same Focke–Wulf Fw 190 that is shown in the previous image but it could be another airframe altogether. The former Luftwaffe aircraft appears to be flying over olive groves, which makes sense, as the 79th Fighter Group was assigned to the 12th Air Force operating in North Africa, Sicily and Italy. The orthographic film used by the photographer gives the appearance of a colour shift. This may be later as the rudder now sports red, white and blue stripes. Photo: USAAF

Another shot of the Focke–Wulf Fw 190A captured by the 79th Fighter Group. It is interesting to note that today, the 79th Fighter Group became the 79th Test and Evaluation Group in the early 1990s, and then was consolidated with another group to become the 53rd Test and Evaluation Group. One wonders whether the test and evaluation experience won by the 79th on 109s and 190s during the Second World War played a part in this new assignment. Photo: USAAF

A close-up of the 85th Squadron Flying Skull emblem. There were two Fw 190s procured and flown by the 79th Group. The colour image in the inset is likely the same as the larger photo, but there are differences—the inset photo has a foot step near the wing root that is missing in the larger shot. The call sign for the 85th was “DICKEY”. Photos: USAAF

On 1 January 1945, 404 Fighter Group 508 Squadron’s airfield at St-Trond, Belgium was attacked in Operation Bodenplatte—a front wide attack to destroy allied aircraft on the ground. A Focke–Wulf Fw 190A-8 piloted by Gefreiter Walter Wagner, of 5. II/JG4 was slightly damaged by Allied anti-aircraft fire and was forced to land at the airport of St-Trond. It was captured and painted overall bright orange-red to distinguish it from enemy Focke–Wulf 190s. The aircraft’s code, OO–L, has been described dramatically as standing for OH OH ’ELL, however St-Trond was a Belgian base and OO is the Belgian national code for aircraft registration purposes. Presumably the L was for its intended pilot Leo Moon, the CO. In the end, the aircraft was never flown and was left behind when the 404th left St-Trond. Photo: USAAF

USAAF Focke–Wulf 190 OO-L. The 404th’s CO, Colonel Leo Moon, wrote regarding the all red Focke–Wulf 190; “The aircraft was painted red by a crew who had overheard me saying that I had always wanted to own a red airplane... the OO*L code was placed on it because we had created an ‘imaginary’ fourth Squadron in the Group, and as in the 508th, we used the first initial of the pilot’s name as the last of the three code letters. Since I agreed that we should try and get the 190 into flying condition, everyone considered it my aircraft and added the ‘L’ accordingly... when it was ready I taxied it at all speeds up to near takeoff speed but we had no clearance to fly it from the Anti-Aircraft. After taxiing in I found the tires soaked in hydraulic fluid and they were so deteriorated I felt that they were unsafe... we spent considerable time looking for new tires without success. Then we had to move on and left the Fw 190 at St- Trond. I regret that I wasn’t able to get that 190 in the air – I had even learned the ‘offs’ and ‘ons’ of the switch labels in German but I don’t feel too bad about not flying it. I did get to fly the Bearcat which I believe was more or less a copy of the 190—although no-one ever admits it.” It also looks like the Americans have left the JG4 unit crest on the cowling. Photo via kevsaviationpics.blogspot.ca

Prior to a test flight, we see Canadian Squadron Leader Hart Finley at the controls of an RCAF-marked Focke–Wulf Fw 190 at Soltau, Germany at the end of the war. The aircraft bears the JFE markings of James Francis “Stocky” Edwards who was visiting Finley at the time. We can see where the German markings were either buffed out or spray-painted over. Finley relished the opportunity to understand what he had been up against. Both pilots felt that the Spitfire was superior. For more on Hart Finley, click here. Photo via Vintage Wings of Canada