BATTLE SCARS — Blind Landing at Mossbank, Saskatchewan

The Disappointing Battle in Battle

The Fairey Battle was a British single-engine light bomber built by the Fairey Aviation Company in the late 1930s for the Royal Air Force. The Battle was powered by the same Rolls-Royce Merlin piston engine that gave contemporary British fighters high performance; however, the Battle was weighed down with a three-man crew and a bomb load. Despite being a great improvement on the aircraft that preceded it, by the time it saw action it was slow, limited in range and highly vulnerable to both anti-aircraft fire and fighters with its single defensive .303 machine gun.

During the "Phoney War" which took place prior to the Battle of France, the Fairey Battle recorded the first RAF aerial victory of the Second World War but by May 1940 was suffering heavy losses of well over 50% per mission. By the end of 1940 the Battle had been withdrawn from combat service and relegated to training units overseas. For such prewar promise, the Battle was one of the most disappointing of all RAF aircraft.

From August 1939, 739 Battles were stationed in Canada as trainers in theBritish Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Most were used for bombing and gunnery training with a small number equipped as target tugs. Some aircraft had the rear cockpit replaced with a Bristol Type I turret for turret-gunnery training. Although the Battle was retired from active use in Canada after 1945, it remained in RAF service in secondary roles until 1949.

The following story is from RCAF air gunner John Moyles who learned his craft on the Fairey Battle at No, 2 Bombing and Gunnery School, Mossbank, Saskatchewan

The Battle in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan

BCATP mechanics ready a Fairey Battle out on the Canadian prairie. RCAF photo

A BCATP Fairey Battle Gunnery Trainer inches close to a photo airplane over the Canadian prairies in winter time. RCAF photo

A Fairey Battle (2072) of No.3 Bombing and Gunnery School, MacDonald, Manitoba churns through the cold prairie air. Photo via Wendy Relf

Related Stories

Click on image

Landing blind at No.2 Bombing and Gunnery School, Mossbank

At Gunnery School we trained on Fairey Battles.

These aircraft had seen service in France before Dunkirk. Some of the Staff Pilots had flown them in combat. I didn’t realize this until I asked a Pilot why there were square riveted patches on the fuselage. He replied, “bullet holes.” This brought the war a little closer.

The gunner’s open cockpit with its free Vickers.303 machine gun was entered through a trap door in the belly of the aircraft. The trap door kept freezing shut so Maintenance removed the door. Gunnery exercises carried two students crammed into the open cockpit designed for one man. One Gunner stood up behind the gun. While the second Gunner hunkered down on the floor with his feet braced on either side of the hole in the belly, landscape flew by underneath, fumes and exhaust swept back up through the hole and many a meal was spread over the prairies.

One cold November day in 1941, we took off for an exercise. I was on the floor watching the runway rush by under my feet. 500 feet off the end of the runway a glycol coolant line in the engine ruptured, spraying hot glycol over the pilot’s windscreen. Unable to see, he put on his goggles, pushed back the canopy and stuck his head out, as he started his turn back to the airport. His goggles immediately covered with glycol. He pulled off his goggles and got the full force of the hot fluid on his eyes, rendering him blind.

By this time we were letting down, wheels up, approaching the runway at a ninety-degree angle. Huge drifts of snow paralleled each runway. The Battle hit the first drift belly first, ploughing snow up through the hole and forcing me up beside the other Gunner. The aircraft jumped the runway, hit the opposite snow bank forcing in more snow and almost pushing us out of the cockpit. The aircraft slid to a stop in a nose down, tail up attitude. When the emergency crews arrived we must have been a humorous sight. Two Gunners perched on top of a snow filled cockpit and the pilot staggering around in the snow, completely blind.

The Pilot spent a week in hospital, but returned to the flight line. He was known as the man with the well-oiled eyeballs. It was the cushion of snow in the gunner’s cockpit that saved us from injury. What if we had hit the cement runway instead of the snowdrifts, or worse, nosed in?

By Wireless Operator/Air Gunner John Moyles

Though configured as a Target Tug and not a gunnery training Battle, we can see clearly the belly hatch at the rear of the wing between the tires. This particular Battle, RCAF serial 1649 was involved in a fatal crash at No/ 4 Bombing and Gunnery School at Fingal, Ontario in 1940. RCAF Photo

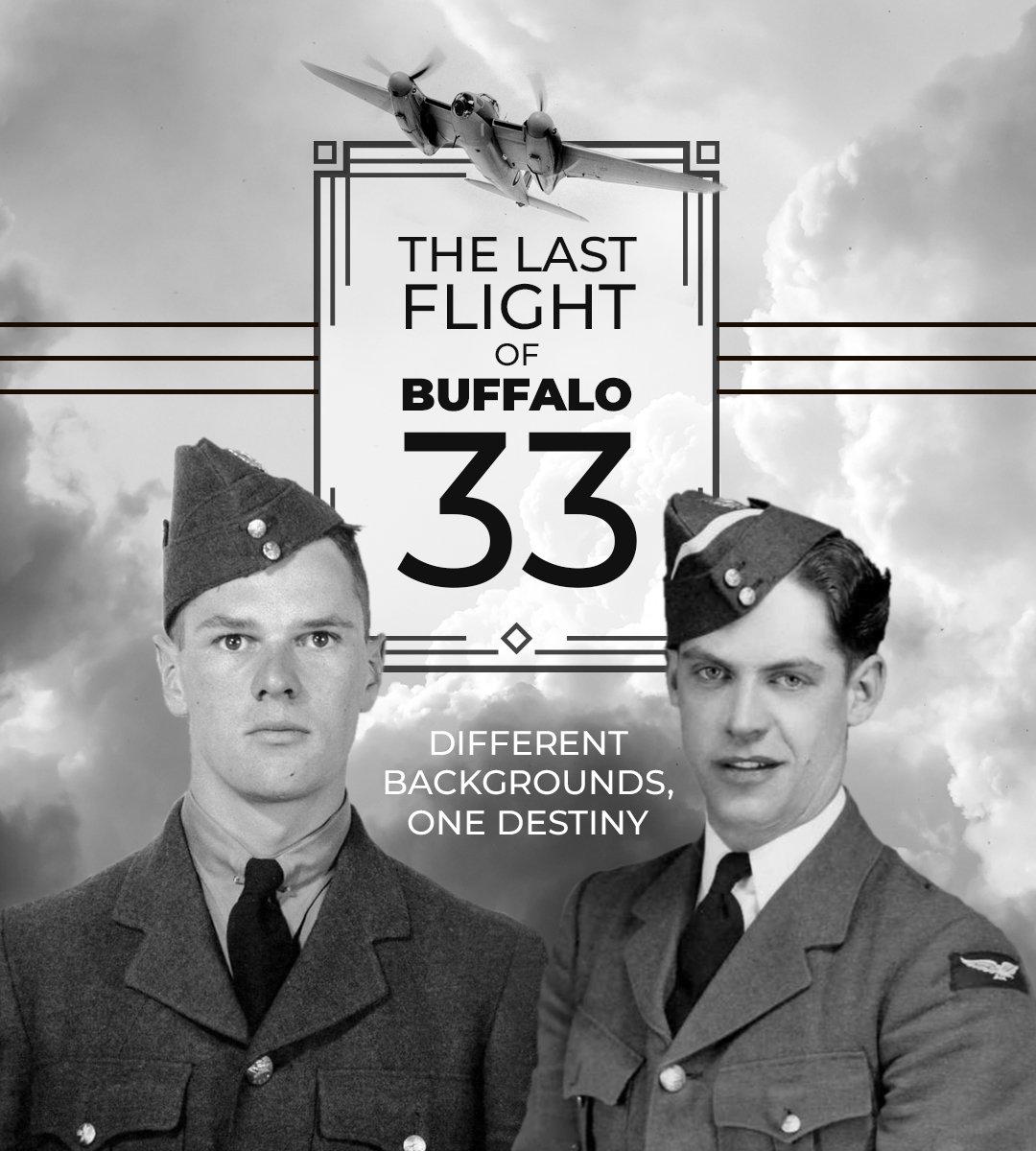

Gunner John Moyles (standing at right) poses with his 422 Squadron RCAF Sunderland crew. John Moyles Photo

Mark Peapell of the Atlantic Canada Aviation Museum sends us this shot of Mossbank's Battle flightline. Though not winter, it demonstrates three different markings used for Battles at Mossbank. In the foreground, Battle 1710 (Ex RAF P6544) wears the European style camo, while immediately behind is most likely in all yellow. In the far distance is a Battle in the black and white “Oxydol” paint scheme of a Target Tug. Battle 1710 was eventually converted to a Target Tug in 1943. Photo via Mark Peapell

Another Mossbank Battle, with evidence of Devil artwork on the fuselage that predates a boxing kangaroo with Popeye blasting away from her pouch... clearly the work of Aussie gunners. Photo Mark Peapell