OXBOXES OVER THE PRAIRIES

This past summer, while researching images of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan operations at No. 36 Service Flying Training School at Penhold, Alberta, I went to one of the greatest and least likely sources of photographic historical records—the photo/social media site known as Flickr. It is here, more often these days than “official” sources like a country’s national archives, that I have found a deep well of personal photos from veterans of the Second World War. In Flickr and other sites like it, the loving sons and daughters of airmen of the war have scanned their father’s albums and created virtual albums, sharing them with anyone who is interested. Thanks to Flickr and its kin, vast numbers of previously unseen personal images of life in the war-torn world of the early 1940s are now available.

These images help us see, feel and understand what life for the ordinary airman was like in this period. In searching for Penhold photos, I came across three albums of varying sizes. There was a huge collection of images from an Australian airman who was part of the last SFTS course at the RAF’s Penhold facility. There was another large collection of images from a young Scotsman who served as an Airspeed Oxford mechanic there in the middle of the war. And there was a small album from a Canadian airman who passed through there in 1942. Together these images show us that Penhold was a busy base, where students loved flying in the vast Alberta prairie and challenging Rockies.

Penhold, being a Service Flying Training School of the RAF, operated Airspeed Oxford aircraft of the RAF, shipped over from England and assembled in Canada. The Oxford, nicknamed the ‘Oxbox’, was used to prepare complete aircrews for RAF’s Bomber Command and as such could simultaneously train pilots, navigators, bomb aimers, gunners, or radio operators on the same flight. In addition to training duties, Oxfords were used in communications and anti-submarine roles and as ambulances in the Middle East. The Oxford was the preferred trainer for the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS) and British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) which sent thousands of potential aircrew to Canada for training.

Although the Oxford was equipped with fixed-pitch wooden, or Fairey-Reed metal propellers, the cockpit contained a propeller pitch lever which had to be moved from “Coarse” to “Fine” for landing. This was done to reinforce this important step for training pilots. Oxfords continued to serve the Royal Air Force as trainers and light transports until the last was withdrawn from service in 1956. Some were sold for use by overseas air arms, including the Royal Belgian Air Force.

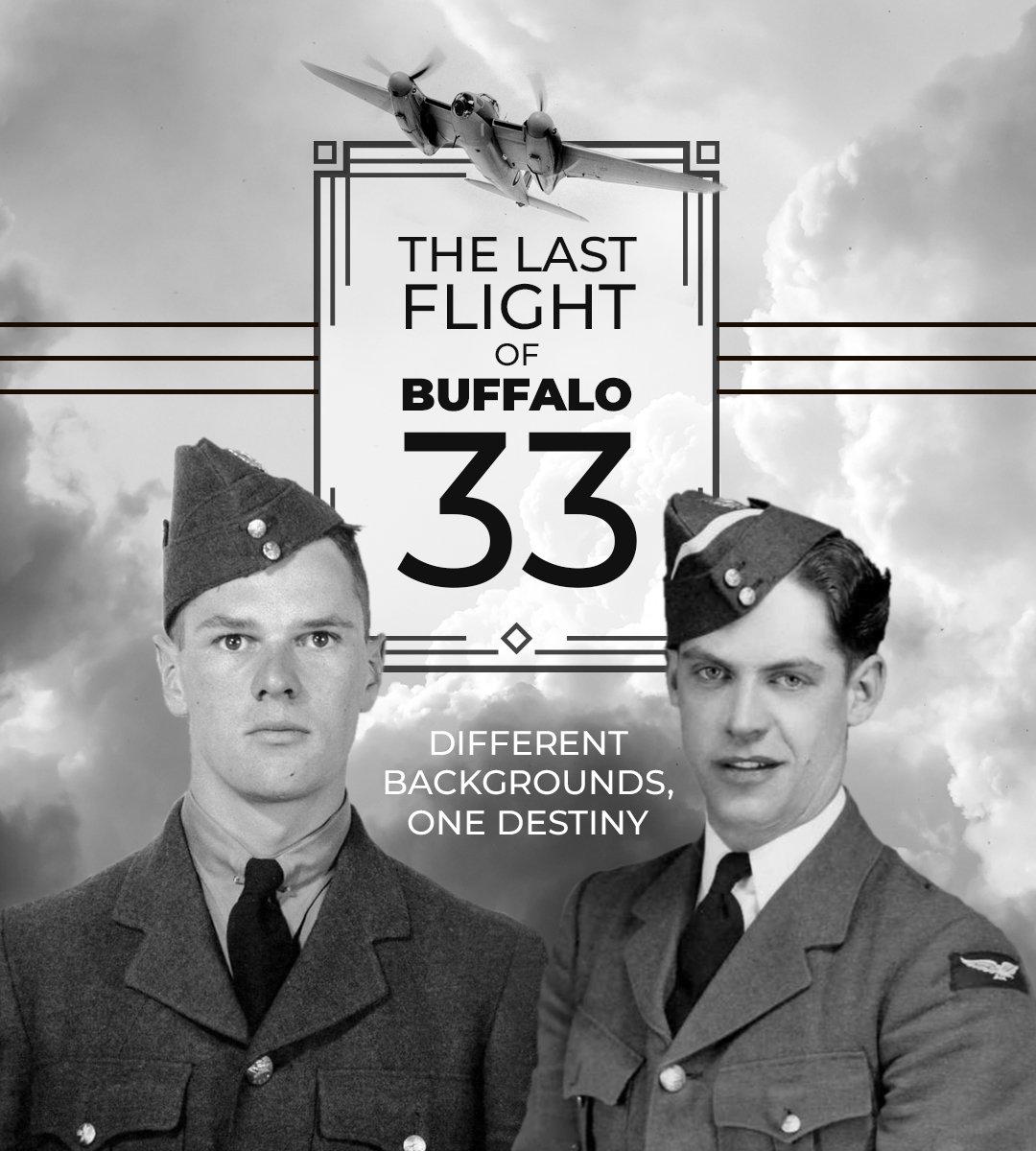

The Penhold Album of Flying Officer Ray Morgan

The first and most extensive collection that I came across on Flickr was that of Australian Lee Morgan, who scanned the photographs from his father’s personal albums as a tribute to his father, Flying Officer Ray Morgan RAAF (439600). The images provide spectacular insights into the many aspects of life on an RAF-run Service Flying Training School—the Oxford aircraft in detail, formation and cross-country flying, the horrific crashes, the daily sporting life, celebrations and what the men did on leave.

In particular, the images of large formations of Airspeed Oxfords flying over recognizable geographical locales throughout western Alberta and the Rockies show us that not much has changed. Vintage Wings aircraft and our pilots still regularly operate in these regions in British Commonwealth Air Training Plan aircraft.

Today, thanks to Vintage Wings of Canada’s western cadre, farmers and tourists alike can, from time to time, look up and see a single yellow trainer lumbering through the skies of God’s Country. But back in 1944, when Ray Morgan and his mates from Down Under were in the area, the sky was yellow with gaggles of thundering twin-engine Airspeed Oxfords, rising and falling in harmony, piloted by the best young men from the antipodes. There is no doubt that these sights were so common back then that Albertan cowboys probably did not even look up when a dozen Airspeed Oxfords and their 24 roaring Cheetah engines shook the landscape from horizon to horizon.

Thanks to social media sites like Flickr, these amazing personal images from one man’s weathered album can help a thousand people of today better understand the conditions, joys, terrors and accomplishments of our young men more than 70 years ago. I hope that in the years ahead, I will begin to see more and more of these postings on Flickr and other sites. With national institutions like the National Library and Archives of Canada facing cutbacks and losing a grip on the time-honoured practice of recording history in all its minutia, perhaps the true repository for history will be social media in the years ahead. For certain, it is the pride and work of the sons and daughters of these men, who now have access to this form of repository, which will keep these stories and images alive. As never before, these images may now see the light of day, for in years gone by, written and visual records such as these, if they were collected at all by our institutions, would disappear into the hermetically sealed and temperature controlled vaults, accessible with considerable effort to only qualified individuals. I thank social media for doing the job our governments no longer deem critical enough to do.

So, enough complaining! Let’s take a look at these three albums starting with Ray Morgan, Royal Australian Air Force.

When Ray Morgan (left) arrived in Canada, he was already an accomplished flyer, having completed his Elementary Flying School training in Australia at No. 5 EFTS at Narromine, New South Wales. Here we see him with his classmates at Narromine in December of 1943, in the heat of an Australian summer, but wearing cold weather gear. They would soon need it in Canada. Sending these pilots to Canada for wings training surely meant they arrived with rusty skills. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

The pilots of No. 36 Service Flying Training School (SFTS), Course Number 105, (probably both A and B flights). This was the final course through No. 36 at Penhold. Royal Australian Air Force student pilot, Ray Morgan, is fifth from the right in the third row. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

The Last of the Best. A close-up of the Course 105 group photo reveals the beautiful young boys of Australia—most of whom would be no older than 20 years. An earnest looking Ray Morgan stands at centre. Each young man, wearing the white cap flash of the student airman (pilot, bomb aimer, navigator, etc.) has completed approximately 80 to 100 hours at an Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) in the west of Canada or, as in the case of Morgan, back home in Australia. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Related Stories

Click on image

The Royal Canadian Air Force ordered 25 Oxford Is in 1938 and they were taken from RAF stocks and shipped to Canada in 1940. They were assembled by Canadian Vickers at Montréal and issued to the Central Flying School. They were later joined by large numbers of RAF-serial numbered Oxford aircraft, like this one, to equip the Service Flying Training Schools operated by the RAF. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Oxfords on the flight line at Penhold. A pilot, parachute under arm, chats with a mechanic after landing. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Ray Morgan (third from left in second row) poses with his entire B-Flight—the instructors, students (thirty or more) and mechanics of Course 105, B Flight. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

A photograph of the tight cockpit of the Airspeed Oxford. Pilot and instructor sat shoulder to shoulder as if in an automobile, but with even better visibility under a greenhouse canopy. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Another great photograph by LAC Morgan, RAAF, of the cockpit of an Airspeed Oxford, clearly showing all the controls the student would have to master—a far cry from the simplicity of the Tiger Moth of Elementary Flying Training School. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

A very descriptive illustration from Flight Magazine tells us what some instruments and mechanical devices in the previous photograph are used for. Image via FlightGlobal

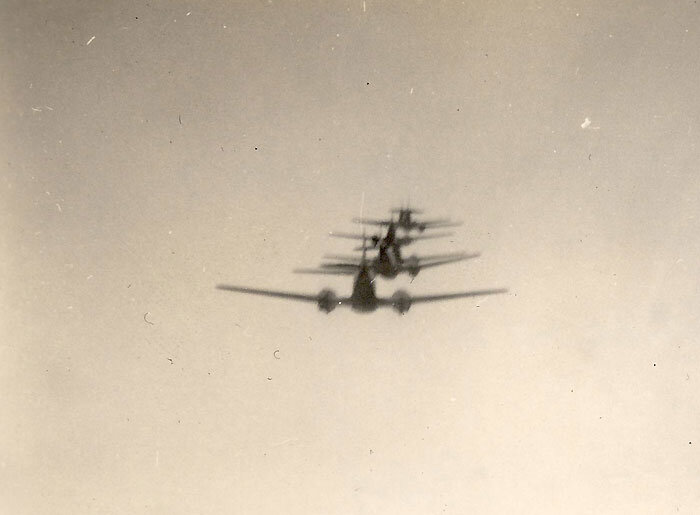

There were several images in Ray Morgan’s album showing pilots in the left command seat of an Airspeed Oxford in which he was a passenger. This leads us to believe that the large number of following photographs, which show various large formations of Airspeed Oxfords, were taken during at least three different flights. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Looking over the nacelle of the starboard Cheetah engine, Ray Morgan snaps a gorgeous portrait of a single “Oxbox” backlit by a prairie sun. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Three Oxfords thunder in line astern formation over a snowy Alberta foothill landscape. This is one of the most elegant angles for the boxy-looking Airspeed Oxford, showing her snarling Armstrong-Siddeley Cheetah radial engines.

Another photo of a trailing Oxford taken from a rear port of some kind. Here we look straight down on two RAF pilots as they hold station behind and below, with their faces craning upwards. We are not sure if this was taken on the same flight as the previous photo, as there is no snow on the ground, just dry farmland. Possibly, though, it could be that the aircraft has flown down out of higher ground where snow was still lingering and that this is the same day. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Two leather-helmeted young aviators move in close to the aircraft that Ray Morgan was flying in. It is doubtful that he has simply changed lenses on his camera as this was the 1940s. Looking at this image I can just imagine the thoughts in the minds of these young men who likely have no more than 100 to 200 hours flying time. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Most likely taken in the line astern formation of the previous photo, this image shows that Morgan’s aircraft was not leading, but in trail behind at least one other Oxford—and pretty close at that. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Looking out the front of the Oxford, Morgan captures six fellow Airspeeds in line astern. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

The pilot of Ray Morgan’s Airspeed Oxford moves in below a large gaggle of Oxford trainers, sliding in astern of the centre grouping. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Morgan’s aircraft lines up with three other Oxfords, which we believe to be a component group of the previous formation photo. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

In formation, a group of Airspeed Oxfords head across the prairies of Alberta. From here, we can see Oxford No. 8 leading. The ports visible on the port side of No. 8 are how Morgan was able to take his beautiful images. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Morgan, sitting at the port side window of the Airspeed Oxford as it leaves Banff behind and climbs to the northeast, heading over the dam at the western end of Lake Minnewanka, separating it from the smaller Two Jack Lake, just visible at the edge of the cowling. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

A flight of Oxfords rumbles across the prairie landscape on a hazy day. With not many visible landmarks, it was easy to get lost on the wide open prairie. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Morgan in his Airspeed Oxford scoots past a mountain, bringing Lake Minnewanka into view, looking from the east to the west, approaching from the Calgary side towards Banff. Rounding the bend in the lake ahead would bring Banff into view. To the left rises the base of Mount Girouard and Mount Inglismaldie, the highest peaks in the Fairholme Range of the Rocky Mountains. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Morgan, looking out the starboard side of his Oxford, captures two more “Oxboxes” snuggled in tight echelon right formation. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

An Oxford climbs out of No. 36 Service Flying Training School at Penhold. Student pilot Ray Morgan snaps a photograph of the seven hangars and flight line of the newly constructed base. We are east of the airfield and looking west. Penhold did not have the standard triangular layout of runways. Today, the BCATP airfield is known as Red Deer Regional Airport and the community of Springbrook. Today, the home of Springbrook is the home of the Penhold Air Cadet Summer Training Centre (PACSTC). Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Another photograph shows part of a large echelon right formation of Airspeed Oxfords from Penhold thundering in the early morning light toward the Rocky Mountains. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

A flock of “Oxboxes” thunder together across the Alberta sky under a warming sun. If any of the Airspeed Oxfords in these shots belonged to the RCAF, we would be able to tell readers the fates of any aircraft. As nearly all the Oxford aircraft in Canada, except the original batch of 30, belonged to the RAF, we have no access to the serial number records. If anyone has records of the fates of RAF Oxfords, let us know. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Looking over the starboard engine nacelle and wing, Morgan captures an excellent portrait of two Oxford pilots in Oxford 76 sliding in close. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

A close-up of the same photo shows the two pilots keeping a close watch on Morgan’s Oxford. The position of the wing tip in the image shows us just how close these young and relatively inexperienced pilots were willing to get. These lads would not have much more than 100 to 200 hours total flying time. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

During one formation flight, an accompanying Oxford peels away from the formation, showing off her beautiful lines in silhouette. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

A Penhold Oxford makes a steep right turn over Banff, Alberta in the Rocky Mountains, with the meandering Bow River to the left. The layout of the town is much the same as it is today with Banff Avenue, the main drag, clearly visible off the leading edge. The same Bow River runs from here downhill, out of the mountains and into Calgary—the perfect navigating tool when the weather was good. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

A nice tight formation of Oxfords over Alberta. The skills in maintaining formation in larger and less responsive aircraft like these Oxfords would allow these future bomber pilots to fit into the bomber streams over Germany, flying Lancasters and Halifaxes. Most likely, given the late 1944 dates of these formation flights, most if not all of these pilots would get the chance to make it to England and through an Operational Training Unit in time to take part in the final battles against Germany. Likely training leaders were looking further out to the continuing war against Japan. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

This image is the same as the colourized one in the opening title graphic. It shows at least three Penhold Oxfords flying over Red Deer, Alberta headed north. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

The same group from the previous photo with the distinctive shape of Sylvan Lake, Alberta in the distance. When trying to figure out where this was, I simply fired off the photo to Todd Lemieux and John Sterchi, two of our Yellow Wings pilots familiar with flying in this area. I got an immediate email stating unequivocally that this was Sylvan Lake. Given the position of the lake in this image, the town of Red Deer would be just below them or slightly to their right. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Another sunlit photograph of a mass formation thundering across the Alberta prairie. This shows us that these students are close to getting their wings and becoming finished pilots of the RAF and RAAF. Oxford 43 (AS367) above (next to the photo ship) was earlier involved in an air-to-air collision and was forced to make a wheels up landing in the snow at Penhold’s relief airfield at Innisfail. The other aircraft did not fare as well. See image below in the Cunningham Collection. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

A single Airspeed Oxford about to touch down at No. 36 SFTS Penhold, Alberta. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Not all landings or circuits were successful. In the three albums I found on Flickr, there were crash photographs in all of them. The wooden and fabric-covered Oxford did not fare well in an accident. The severity of the damage to the cockpit area of this de Havilland-built Oxford II leads one to assume serious injury or death to its occupants. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Unlucky No. 13—Another angle of the same crash scene from the previous photograph. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Judging by the prairie grass and mud in the landing gear of this Oxford and its flaps set for landing, it was attempting a wheels down emergency landing when the wheels dug into soft ground and the Oxford flipped onto its back. One of Morgan’s Penhold mates (possibly Al Bartlett) poses with the totalled aircraft—a sobering reminder of what could happen during training. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Same accident as previous photograph. Both propellers are undamaged, leading us to believe that both engines had quit during flight, possibly from fuel starvation. The condition of the cockpit indicated severe injury to its occupants. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Another angle on the previous crash scene shows us just how deep the grass was in this field, burying half of the fuselage. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

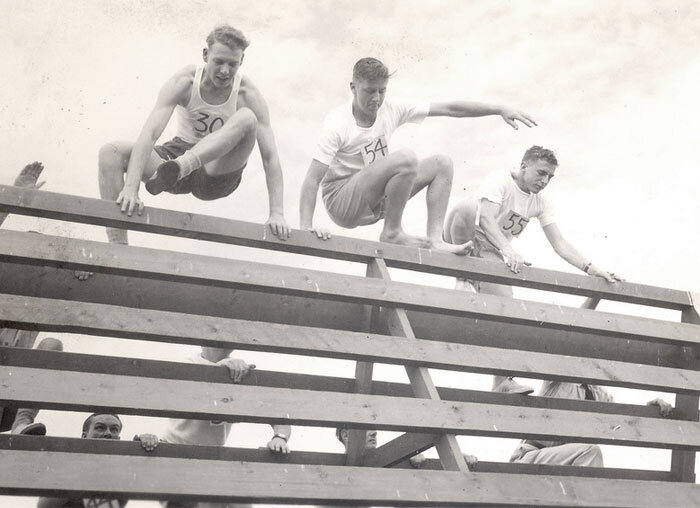

For Australians, rough and tumble physical fitness was de rigueur. In Morgan’s album, this group shot was taken during a competition with rival New Zealanders at The Australian Rugby Union IV in April 1944 at Penhold. Morgan is at right in back row. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Athletics were an important part of staying fit and becoming competitive. Here we see RAAF students pilots (Dick Gray (55) and Peter Bury (54)) scrambling over a fence structure in an obstacle race during an Athletics Carnival held at Penhold in August of 1944. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

A big mess dinner at No. 36 SFTS Penhold with students and flying instructors enjoying some Calgary Beer and good food. The occasion was the graduation of the pilots of Course 105. It appears that Ray Morgan is at the head table (between the “R” and the “A” in RAF). By blowing up this image I was able to get a close look at the programs at the tables—a souvenir that Ray Morgan took home with him to Australia. See next photo. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

The program for the big mess dinner to celebrate the graduates of Course No. 105 B Flight. The party started at 8 PM, 19 October 1944... and ended much later! All of the 34 graduates were with the RAAF, except one lone Scotsman. The dinner featured “Fried Chicken Southern Style with Roast Ham seasoning.” Toasts were made to the King, the Commanding Officer, Guests, and the Instructors. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Being a celebration of the winging of Course 105 student pilots, the centrepiece was, of course, a set of wings. Instead of an RAF or an RAAF acronym in the centre, there is a question mark. Ray Morgan is at far left with possibly Dick Gray standing and facing the camera. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Soon to be Pilot Officer Ray Morgan (third from left) still wearing his Leading Aircraftman propeller insignia, joins his Course mates and instructors (those with wings) for a toast and a smoke beneath the bunting at the Airmen’s Mess at Penhold. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

The boys (and they do look like boys) are getting a little happier as the evening progresses. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Ray Morgan (at the very back on the left), his Penhold instructors and mates seem to be getting well oiled. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Clearly, these lads have had more than just the one Calgary brand beer. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

While at Penhold, Morgan and his pals visited Banff, Alberta. Here we see a photograph taken by Morgan or one of his mates looking down Banff Avenue toward Cascade Mountain rising to 9,800 feet in the background. Today, this scene looks much the same. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Another photo of Banff and the Banff Springs Hotel from Morgan’s photo album. For young men from a relatively flat Australia, the rugged Rockies must have seemed foreign and exciting. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Castle Mountain, a spectacular outcropping of stone halfway between Banff and Lake Louise, can today be viewed from the much less rugged TransCanada highway. These spectacles made the long trip from Australia bearable and memorable enough that many would return for a visit after the war... including Ray Morgan. The pinnacle to the right was named Eisenhower Tower after the Second World War. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Some visiting aircraft at Penhold. In the foreground stands a Douglas C-47A (43-30654) of the United States Army Air Force. Records indicate that this Skytrain, flown by a Thomas Walker, was involved in an accident at Athens, Greece in June of 1953. At right is Anson 8247 which was originally issued to No. 4 Training Command on 1 June 1942, for use by No. 8 Bombing & Gunnery School at Lethbridge, Alberta. After mid-November of 1944, it was listed for disposal. To the left is a Cessna Crane, serial number 7889, which was sold to A.J. Leeward of Montréal after the war and then was registered with the U.S. civil register as N69120. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

When Ray Morgan had completed his flying training and had received his wings at Penhold, he travelled back to Australia aboard the troopship S.S. Lurline, celebrating Christmas and New Years’ Day aboard the Lurline, an 18,000 ton American liner of the Matson Line. In this shot taken in Honolulu in 1943 in her troopship configuration, we can see gun tubs on the foredeck and extra rafts secured to her sides. Famous aviator Amelia Earhart rode Lurline from Los Angeles to Honolulu with her Lockheed Vega airplane secured on deck during 22–27 December 1934. Photo via cruiselinehistory.com

Back home in Australia, Ray Morgan continued to fly with the Royal Australian Air Force, which was awaiting the development of the war against Japan. Here he stands with another Oxford in August of 1945 at the Advanced Flying and Refresher Unit, Deniliquin, New South Wales. He was here to keep his skills fresh. During the war, Deniliquin was home to No. 7 SFTS, training some 2,000 RAAF pilots on the Wirraway. By late 1944, No. 7 SFTS was shut down and the base became home to Advanced Flying and Refresher Unit (AFRU), where pilots returning from Europe and Canada could keep their recently won skills fresh. The AFRU itself disbanded on 1 May 1946. Deniliquin was the final destination of various RAAF units returning from the Pacific War for disbandment. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Pilot Officer Ray Morgan, in peaked cap and tie at the controls of an Airspeed Oxford once again, this time at the Advanced Flying and Refresher Unit after having crossed the Pacific on S.S. Lurline.

Morgan, this time with a leather helmet, poses for a portrait for old times’ sake at Deniliquin, NSW. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

When Morgan reached Australia he was first posted to No. 11 EFTS Benalla in Victoria. It was here that he shot this image—one of the weirdest photographs of a Tiger Moth in flight I have ever seen. It seems the passenger of this Royal Australian Air Force Tiger Moth at Benalla has gone “walkabout”, dropping the side door panel on the front cockpit and walking out to the outer wing struts for better view of the Australian landscape. Ray Morgan’s son Lee says he has no details as to why this was done—perhaps a bet or a lark by returning combat pilots looking for excitement. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Another view of the RAAF wing walker. If anyone has any information on this incident, let us know. While Morgan was at Benalla, volunteers were sought to ferry some Tiger Moths from Narrandera NSW to Sydney, and Ray put his hand up. This was on 27 March 1945, and he had not flown a Tiger Moth since 6 January 1944. The first leg was Narrandera to Cootamundra NSW, where he landed heavily and broke the undercarriage slightly. The senior officer then took him up for a checkout before he was allowed to take the repaired aircraft to Sydney via Goulburn, NSW. His son Lee remembers him remarking how tiny he felt taxiing his Tiger Moth through rows of B-17s then parked at Sydney airport. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

Young Raymond Morgan, of the Royal Australian Air Force, photographed on 3 November 1944, shortly after earning his wings at No. 36 SFTS. A month later he was aboard the troop carrier S.S. Lurline, headed home to Australia. He wears the white armband of an LAC who has recently been commissioned as a Pilot Officer but is awaiting his insignia. At right is a colour photo taken in 1986 when Ray Morgan visited Penhold and Alberta. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

In 1994, Australians of Penhold Course No. 105 had a reunion in Adelaide, South Australia on the 50th anniversary of their wings parade. Unlike wings courses from earlier in the war, these pilots were shipped home as the war was winding down. That is why there are so many still alive in this reunion photograph. Ray Morgan is standing third from the right in the back row. Photo via Ray Morgan Collection

The Penhold Album of Aircraftman First Class Alexander Cunningham

Young Alexander Cunningham served with the Royal Air Force from 1940 to 1946 as an aircraft mechanic. As such, he was sent the long way to Canada to serve at RAF-run flying schools of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, including No. 36 Service Flying Training School at Penhold. At various times from the autumn of 1941 to the spring of 1943, Cunningham was based at Gananoque, Ontario, a relief landing field for No. 34 SFTS Kingston, Ontario and at Big Bend Airfield at Penhold, Alberta.

The young mechanic suffered a head injury when an escape hatchet, which was strapped to the outside of an aircraft, broke loose and struck him. Cunningham spent several weeks in hospital before he was invalided home, this time to Liverpool, England.

After his recuperation Cunningham served with a salvage and repair crew on Scotland’s Solway coast, dealing mostly with flying boats in Wig Bay and land-based aircraft at Castle Kennedy, until he was demobilized in 1946. Cunningham liked what he had learned in the RAF, so after the war, he practiced as civilian aircraft engineer with various companies and took a jet conversion course in 1963. He retired from aviation in 1982 after 40 years in the business, and died in 2004 at the age of 85.

A couple of photos of Aircraftman Alexander Cunningham. At left we see a very proud young Aircraftman Second Class Cunningham in a formal portrait taken shortly after his induction. At right we see him studying Paul Sullivan’s War Atlas. This was a book of reference maps published in Chicago USA for use in conjunction with Paul Sullivan’s broadcasts on Columbia Radio. Cunningham would learn skills in the RAF as an aircraft engineer that he would keep and utilize throughout his civilian career as an Aircraft Maintenance Engineer. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

Alexander Cunningham joined up with the Royal Air Force in 1940. Soon he would be sent overseas to Canada to assist as a mechanic with the Royal Air Force operations as part of the British Commonwealth Air Training plan. His journey across the seas would take two ships and a stopover in Reykjavik, Iceland. They boarded the troopship (T.S.S.) S.S. Leopoldville in Greenock on 21 August 1941, dressed in tropical gear as a ruse for dockyard spies. Well out at sea, they were issued colder weather gear, something they would definitely need where they were going. The ship reached Reykjavik on 24 August 1941 and Cunningham was transferred to Helgafell Camp at Alafoss, where the British had constructed temporary barracks for transiting troops and airmen. SS Leopoldville was an 11,700 ton passenger liner of the Compagnie Belge Maritime du Congo. She was converted for use as a troopship (TSS) in the Second World War, and while sailing between Southampton and Cherbourg, was torpedoed and sunk by the U-486. As a result, approximately 763 soldiers died, together with 56 of her crew. Photo via u-boat.net

After a lengthy stay of several weeks in Iceland at Alafoss, Cunningham and his RAF compatriots then boarded the troopship SS California which lay in Hvalfjord. On 3 September 1941, this ship weighed anchor and steamed in the company of two other ships to join a convoy of sixty five ships bound for Canada. SS California was a British steam-powered passenger ship of 16,792 tons built in 1923 for the Henderson Brothers Ltd, Glasgow. In 1939 she was requisitioned by the Admiralty and converted to an Armed Merchant Cruiser, and from 1942 she was used solely as a troopship. On 11 July 1943, when about 300 miles west of Vigo, Spain, the convoy was attacked by three Focke-Wulf Fw 200 aircraft. California and another troopship, the Duchess of York, were set ablaze. The ships were abandoned and then sunk by RN torpedoes. Photo via Wikipedia

Alexander Cunningham’s first photograph in Canada—a view of Halifax harbour from SS California that is less than flattering. His personal feelings about this war town were also not so positive as he took to calling it the Garbage Can of Canada. Being a Haligonian myself, I winced when I heard this the first time, but then I realized that my hometown Halifax was a different place during the war. Polluted, dirty, crowded with sailors, airmen and soldiers and all the attendant sin and evil that they attract (Bars, Brawls and Bordellos), Halifax must have been a decidedly busy if unattractive city with no time to do anything except provision ships and send them to war. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

The sign at the entrance to No. 36 SFTS at Penhold, Alberta near Red Deer, was the same as you would find at any of the BCATP establishments. Young Alexander Cunningham would have seen a similar sign at the entrance to the airfield at Gananoque, Ontario, a relief field for No. 31 SFTS Kingston, Ontario where he had also worked during his BCATP days in Canada. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

For a young man used to the rolling bucolic greenery of “This Sceptred Isle”, the flat prairies of Alberta might have seemed rather bleak and uninviting. In this view, we see the hangar line of No. 36 SFTS... rising not that far above the plain. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

A couple of photographs of Alexander Cunningham at Penhold. At left is a summer shot of the young RAF mechanic standing on the duckboard outside an H-hut barrack building where he lived between 1941 and 1943. At right he is wearing soiled coveralls and a parachute, about to go for a flight in a North American Harvard in the winter. This shot was likely taken at Relief Field Gananoque of No. 31 SFTS as that was the type of weather he had during his stay there. Photos via Alexander Cunningham Collection

Alexander Cunningham doing guard duty at No. 36 SFTS Penhold. There were many reasons a young LAC would be required to do guard duty, but the most common was because his status was on hold and he had not yet been given a specific task or placement. Many an airman was required to stand guard duty awaiting final orders to go on to the next stage of his career. There were also duty guards and the odd guard who was being punished for a simple transgression of rules. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

An evocative image of airmen lounging in a crude barrack hut at Penhold. The man lying on the bunk is Herman “Slim” Joseph Knights, a Canadian aviation legend. Knights went on to Squadron 57 RAF flying Lancasters and was shot down on 24 December 1943. When he returned to his home at Port Alberni, BC, he was involved with several aviation start-ups. He flew DEW Line supply flights, was a bush pilot, conducted firebombing with Skyways, and eventually, was one of the group who purchased Skyways and started Conair Aviation Ltd., where he served as Vice-President. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

Like Morgan’s photo album which precede this. Cunningham’s album contained a lot of sporting images. Sport in all its forms was certainly how young airmen and student pilots relieved the stresses of boredom and hard work. Where Morgan’s Australians played rugby, Cunningham’s Brits assembled teams for football. The station team, known as the Penhold All Stars, pose for a photograph in 1942. A list of team members is listed on the back of the photo in the album. They are in no clear order, J.E. Hopwood; A. Massie; H.J.D. Hogg; J.S. Chambers; L.L. Gill; D. Allan; E.C. Watkin; H.G. Bond; T. Fisher; T. English and G. Harper. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

Of course, in Alberta they have 10 months of winter and two months of poor soccer weather. With the Alberta grasslands behind him still showing signs of residual snow, RAF airman J. E. “Ginger” Hopwood of the Hut 11 Ragamuffin Eleven attempts to head the ball (“nod” it in) during an inter-barracks game of soccer. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

On what seems like a warmish and sunny day out on the Alberta prairie, a few RAF and RAAF airmen don skates and pick up sticks for a game of shinny. If you are a Canadian, you will be able to tell, by the way all three of these men are holding their hockey sticks, that they have not played much hockey. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

A lovely and engaging photograph of six fellow airmen of Alexander Cunningham taken on the hangar roof at Innisfail, the relief landing field for No. 36 SFTS Penhold. A relief field was designed to take some of the load of student pilots doing touch and goes and circuits, thereby “relieving” the home field at Red Deer/Penhold. Note the ladder leaning against the roof and the fact that the young men have brought the hangar dog up with them. For more on the history and heartwarming concept of the Hangar or Squadron Dog, click here. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

This is either Tiger Moth 1125 or more likely 1128, both of which were attached to No. 32 Elementary Flying Training School at Bowden, Alberta, some 40 kilometers to the south of Penhold. Unlike the Boeing Stearman aircraft originally used at Bowden, this Tiger Moth is equipped for winter operations with the cockpit canopy. Both 1125 and 1129 were originally ordered as PT-24s for the United States Army Air Corps, but were channeled into the RAF and the BCATP using the Lend Lease program. Tiger Moth 1128 had nearly 2,100 hours on it in the three years it served at Bowden—a considerable number of hours. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

In addition to keeping the fleet of Airspeed Oxfords in operating condition, RAF mechanics like Aircraftman Cunningham were often required to salvage and recover damaged or crashed aircraft. Here Oxford, Fuselage Number 63 (AT448), has run off the runway at Penhold’s relief field at Innisfail, Alberta and has come to grief in a drainage ditch. An aircraft in this condition was likely deemed un-repairable and its various usable components cannibalized for repair to other Oxfords. The mainly wooden wing and frame of the Oxford was easily shattered when in contact with the ground. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

Recovery crews await the arrival of a Royal Air Force crane to lift the heavily damaged Oxford out of the ditch at Innisfail. While the wings, engines and landing gear are probably totaled, there is still hope that the fuselage is intact. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

A crane is brought in to remove Oxford AT448 from the Innisfail drainage ditch. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

Exuberant and youthful pilots test their skills at Penhold’s Relief Field at Innisfail. Here, the pilots of an Airspeed Oxford force themselves down low on to the prairie airfield. The result of such test of skill might, from time to time, end in disaster. In this case, the extremely flat geography is in the favour of the pilots involved. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

In another pass, some of the airmen on the field at Innisfail have come out of their huts and hangars to watch as the same pilot push their luck even further for a second lower pass. Note the truck in the background. Today, the old relief field at Innisfail is the municipal airport for the town of Innisfail and the triangular layout of paved runways can still be seen. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

Cunningham at the controls of a Ford 1-1/2 ton truck used by the RAF at No. 36 SFTS Penhold and its relief field at Innisfail. This appears to be the very same truck, or at least the same model, as the truck in the previous photograph. The light at the top and the general design are very similar. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

Recovering downed aircraft was in many ways a difficult task, what with grim findings and bad weather. Here an Oxford has crashed into a farm near Penhold after experiencing an engine failure. Aircraftman Cunningham (background) and fellow mechanic Norman Tyson were tasked to recover the wreckage. The old air force euphemism for being killed during training— “He bought the farm”—comes from situations just like this. During the war, if an American pilot crashed his aircraft into a farm or farmland near his training field, USAAC authorities would compensate the farmer for damage to his crops or structures from the crash and ensuing recovery. Unless the pilots bailed out of this aircraft, it is doubtful that they survived. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

Likely a photo taken at the same recovery site as the previous photograph. Aircraftman First Class Alexander Cunningham (left) has removed his cap, and the three airmen are warming themselves around a fire while they work to recover the wreckage of the downed Oxford. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

The wreckage of a Penhold-based Airspeed Oxford lies on one of the three runways at Innisfail’s Big Bend Airfield, so named because it lies just to the south of a “Big Bend” in the Red Deer River, which turns north to Red Deer and then south again for 724 kilometres before emptying into the South Saskatchewan River. This Oxford (Fuselage Number 59) was involved in a mid-air collision with Oxford 47 which managed to execute a wheels up landing on the snow in the infield, right next to the wreck of this aircraft. Note the shattered wooden structure of the wings. It is not clear whether this aircraft, with its wheels down, was taking off or landing when the accident happened or whether it crashed after the mid-air collision when trying to land. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

Another view of the same Oxford 59 after a catastrophic crash or ground loop. As with many Oxford crashes, it seems that the occupants of the fragile cockpit area have suffered greatly. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

Airspeed Oxford (fuselage number 47) after its mid-air encounter with Oxford 59. It has fared better than the other aircraft, though sustaining heavy damage to the engines, propellers and fuselage. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

Airfield fire trucks and crash recovery vehicles surround the devastation of the Innisfail crash site. Judging from the trail of shattered wooden structure, it’s possible that the Oxford cartwheeled to a stop after ground looping or crash landing. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

Looking at the same crash from the other side, Oxford, Fuselage No. 59, looks shredded and utterly broken. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

The close proximity of Oxford 59 on runway and Oxford 47 on infield is interesting. Was 47 taking off with wheel up when it was struck by Oxford 59 while landing? Did the mid-air happen at a very low altitude? If anyone knows the circumstances of this crash scene, let us know. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

The snow on the prairie is quite forgiving if you are properly set up for a wheels up emergency landing. Here, Oxford 43 has slid to a stop on the snow with not much obvious damage. This is backed up by the photograph of the same Oxford aircraft (AS367) flying in formation in a photograph in the previous Ray Morgan Collection. Photo via Alexander Cunningham Collection

On his way home to the United Kingdom, Aircraftman First Class Alexander Cunningham went through Halifax again. This time he boarded the troopship TSS Louis Pasteur, seen here tied up at Pier 21 with SS Aquitania. After the war, her name changed four more times. She became SS Bremen in 1957, then SS Regina Magna, SS Saudiphil and finally she sank under tow as SS Filipinas Saudi I in the early 1980s.

In writing and publishing this story about Penhold and Oxfords and Innisfail and the power of the internet to connect us and keep history alive, I received an email from one of our readers, a Hubert “Hu” Filleul, who, back in the time of No. 36 SFTS, was a teenager in the small town of Innisfail. He sends us this short memoir of life for a young boy in a small town with a big impact from the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Hu writes:

“I attended Innisfail high school during those years so your story about Penhold and Bowden brings back personal memories. Regrettably I do not have any photos of the three airfields around Innisfail.

As a member of the Innisfail Air Cadets, we often went to Penhold (about 11 miles north) where some poor English Corporal was put in charge of us. They had us washing the Airspeed Oxfords and we also got to sit in them. One day there was a pack on the right hand pilot seat so I grabbed it by the handle to move it out of the way. A billow of silk demonstrated that the pack was a parachute. We rapidly made ourselves scarce and my sin was never discovered.

I was also a friend of Allan Anderson, the undertaker’s son in Innisfail, so helped him move some of the bodies that came in from Bowden Tiger Moth trainer crashes. I believe that there are 13 graves in the Innisfail cemetery, of airmen killed during the relatively brief time that Bowden was open. Such a huge EFTS accident rate would not be tolerated these days. The undertaker’s wife, Martha Anderson made the effort to send photos of the graves along with a letter to each family of the deceased. I suppose we were one of the small Canadian towns that was impacted quite a bit by the war. One of the airmen killed was a Squadron Leader Procter, who was the Chief Flying Instructor, I believe. He had managed to move his family from England to a house in Innisfail, which made the tragedy all the sadder. As they went straight into the ground, the story was that he took up a borderline student for a check ride and the student froze on the stick.

The town of Innisfail only had a population of about 1,000 so the few single women and girls were very popular with the 1,400 airmen stationed around us. Even though they were our allies, we teenage boys did not take the RAF airmen’s attentions kindly. They moved in two Mounties, Buzz Rivet and Gus Spohr, to impose law and order. They were smart policemen that did their job largely without making arrests or requiring court action. Under the guidance of Buzz, I got to be President of the “Teen Town” club (part of the ongoing effort to keep us out of trouble). Innisfail and Bowden EFTS also organized weekly exchanges where Innisfail would host the dance one Saturday night in the Armouries and Bowden would host it the alternate Saturday in their drill hall. This worked out very well as both boys and girls were made welcome at Bowden. It so happened that the local shoemaker, Mr. Tedeshini, (can’t remember his first name, probably because I always called him “Mr.”) was a trained bandmaster so we had an accomplished high school dance band that played regularly in the Armouries. Bowden had a cool English dance band of its own.

There was an RAF Wing Commander named Bristow (I think I remember) who was the CO at Bowden. He and his wife had managed to rent a farmhouse that was quite primitive. They invited several local couples including my parents for New Year’s dinner (1943?) The CO’s wife had cooked a goose that she thought was already stuffed but it wasn’t cleaned. My parents said that the drinks and hospitality made up for the goose disaste

The Innisfail satellite airfield was farther away than Bowden’s four miles, as it was six miles west, past the Red Deer River.

I joined the RCAF in December 1950, flew on the Korean Airlift as a Radio Officer, and spent a total of 35 years with DND.”

The Penhold Album of Robert Wellington Barnes, RCAF

Robert Barnes, a native of Ottawa, Ontario, first enrolled in the Canadian Army in 1938 after being initially turned down by the RCAF. But by 1941, he transferred out of the Army and into the RCAF. His Initial Training School (ITS) was at Edmonton which, under the name of No. 4 ITS, was situated in the Edmonton Normal School (Teachers College). He went on to EFTS at Neepewa, Manitoba in the winter of 1941–42, and then on to Penhold for training on the Airspeed Oxford. His later career included Lancaster operations with 419 Squadron RCAF. Barnes’ photo album is thin with photos of Oxford operations while he was there, but there are a few images of an Oxford accident that are compelling as well as images of his early training.

Robert Barnes died in Ottawa in November 2002 at the age of 82.

Aircraftman Second Class Robert W. Barnes lounging in a sunny barrack room at No. 4 ITS, Edmonton. This would be in a wing of the Edmonton Normal School, known as Corbet Hall. Photo via Robert Barnes Collection

Aircraftman Robert W. Barnes (left) striking a handsome and determined pose back home in Ottawa. This image would likely have been taken before he went on to flying training or between EFTS and SFTS as he still wears the white cap flash of a student aircrew member. At right we see Barnes in cold weather flying gear outside his barrack hut at No. 35 EFTS at Neepewa, Manitoba in the winter of 1941–42.

A great image of Barnes’s friends sunning themselves out on the Alberta prairie in 1942. Photo via Robert Barnes Collection

A photograph, apparently taken at Penhold, shows a few of the same friends (with Barnes in the cockpit as well as Lyle Gibson, Jeff Raymond and a fellow named Copping) posing with an Avro Anson. Number 36 SFTS used only Oxford aircraft, so this was taken either at another field or it was of a visiting aircraft. Photo via Robert Barnes Collection

A rather catastrophic crash of an Airspeed Oxford at Penhold. The scalloped metal piece at the bottom right is the upper trailing end of the engine nacelle. Photo via Robert Barnes Collection

One of Barnes’ chums poses with the wreckage of the same Oxford. Photo via Robert Barnes Collection

The same airman from the previous photograph, this time with one of the locals. Photo via Robert Barnes Collection

The author would like to thank Lee Morgan, Alex Cunningham and Catherine Barnes for sharing the images of the fathers they loved so dearly. You are the archivists of the future, keeping the past alive and accessible today.