SELLING VALOUR

When our veterans of the Second World War packed up their meagre collections of personal effects, uniform kit and documents and walked up the gang planks of hulking grey troopships bound for Europe and the Far East, they carried with them the innocence of youth, the trepidations of young men and women about to test their mettle and a powerful sense of immortality. Those that returned, in some cases five years later, were unburdened of their youth, relieved of their invincibility and devoid of any romantic notions about the glories of war. As they boarded trains and headed home across this magnificent country, there was ample time to contemplate and weigh their experiences of war. There was a real sense of the futility and obscenity of war, of great personal loss and tightness brought on by years of deprivation, yet there was an overriding feeling that these past difficult months and years would be the greatest of their lives.

These men and women, these warriors, were not born to it or naturally martial in their outlook. They came from a hardy, simple and uncommonly polite populace, spread like sewn seed across a land some 3,000 miles in breadth. They came from farms, high schools, factories, government offices and a wide sampling of every walk of life. There were heirs to fortunes and men not long off the bread lines. There were men and women of cities and those from more rural roots. There were loners and belongers, freebooters and pedants, lone wolves and team players. They went to war as a scattering of diverse backgrounds, and those that survived and returned, did so as equal parts of one great experience.

The large percentage of them would never don a military uniform again. Most pilots and airmen would never fly again; sailors never sail again, soldiers never fire a weapon again. They chose instead to fade back into the structure of society, like actors exiting a stage behind a scrim, woven back into the fabric of the land, invisible on the street. For the last seven decades, heroes, giants and legends walked unseen among us.

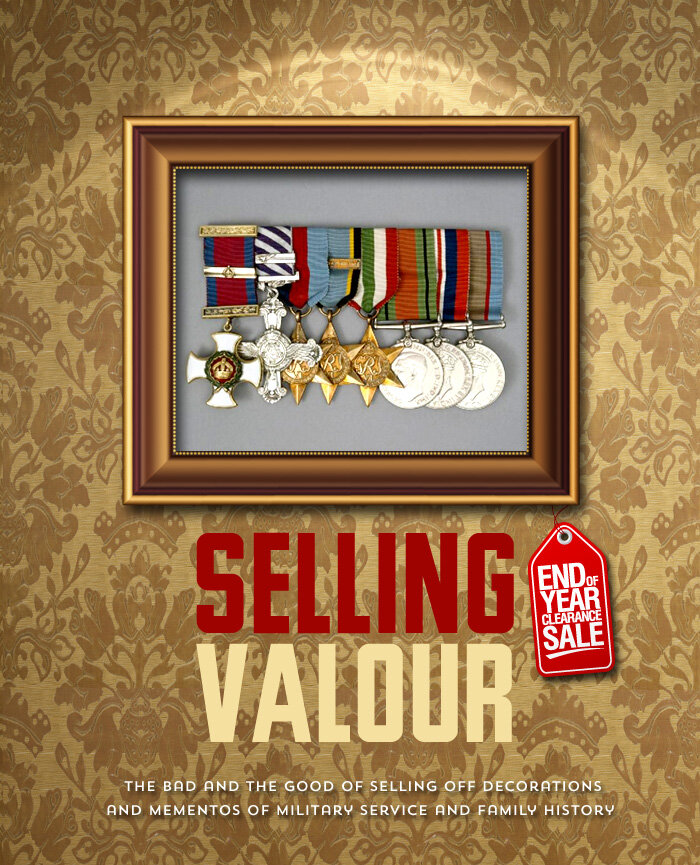

These men brought home with them small personal collections of photographs, artifacts, mementos, logbooks, and bits of uniform—talismans of their good fortune, memories of lost friends, and declarations of their travels and accomplishments. Nearly all kept these tangible memories in boxes and albums, many of which found their way to dusty attics and mouldy basements. Every one of them, however, brought home or was later eligible for certain medals and decorations depending on their theatre of service. These simple things of brightly coloured woven ribbon and non-precious metals were their membership cards to an honoured society of dutiful and honourable men and women, nearly all of whom had made some sacrifice to gain entry—physical and psychological injury, deprivation, deep loss, homesickness and even death. To walk into a room at the Legion Hall with one’s “gongs” on one’s chest was an act of great pride, for they told a tale about your service and confirmed your belonging. A stranger could come up to you and shake your hand, and with a simple knowledgeable glance at your campaign stars and medals, know that you fought in the Far East or the Atlantic or the Pacific. Bars or “clasps” told an even more detailed story of hardship—confirming that you were at Dieppe, Hong Kong, in Bomber Command or the Battle of Britain.

Medals, known as “decorations” and “orders” such as the Distinguished Flying Medal and Cross or the Military Cross earned you greater respect, more knowing glances. The simple colourful array of medals and decorations on your chest could offer a story of rank and gallantry—Air Force Cross, DFC with Bar, Distinguished Service Order or Cross, George Cross, Order of the British Empire and even Victoria Cross. I have met only one Victoria Cross recipient in my life, Private Ernest “Smokey” Smith, and being in his presence, as gregarious, rough hewn and down-to-earth as he was, made me speechless with respect and awe. He wore the simple crimson ribbon of the VC and the cross itself was made from melted down cannons captured from the Russians in the Crimean War.

For all these men and women, the campaign medals and decorations were the singular tell that betrayed their greatness, worn only on days when they gathered together. The families of these men and women were tearfully grateful for their return, were in awe of their accomplishments and proud of the honour they had brought to family bloodlines. For servicemen who had died in the line of duty, all medals and decorations for which they were eligible were sent to their next of kin—in many cases, a young bride.

Upon the deaths of these veterans, their decorations and hidden-away mementos passed on to their sons and daughters and from them even to grandchildren. If the family had a strong tradition of respect and honour for the family member that perished in combat or came home to them a hero, these artifacts were treasured and cared for, as were the stories and memories of service and sacrifice. Today, many a baby boomer has his or her father’s medals polished, mounted in a shadow box of black velvet and on display in a place of honour. Albums and barrack boxes are respectfully and carefully opened on Remembrance Day and memories unleashed, emotions released, honour made public.

Sadly, this was not always the case. Many veterans kept quiet about their service and got on with re-inventing their lives and raising a family. Children took this to mean they did not want to talk about it and as a result, in some cases, never understood the full extent of the story, never fully treasured the power of it all to bring greatness to a family’s heritage. If a childless widow went on to remarry as most widows did, the medals and mementos served only to reopen sad memories of a lost love or to put stress upon the second marriage. They were often kept in storage and upon her passing, meant very little to a child who had no blood connection or foreknowledge of the deceased serviceman.

And so, as that greatest of generations grew old and began to diminish in numbers, a growing percentage of these priceless artifacts and decorations began a silent slide into oblivion or have become detached from their original families. As budgets shrunk and time passed, national institutions such as our own Library and Archives Canada, who once held open arms to uniforms, logbooks and memorabilia, began to turn down the acquisition of our military heritage. One pretty well has to be a seminal figure in Second World War history or be highly decorated for them to accept your diary and logbook these days, and even then there are those in these institutions who would prefer not to have to deal with them.

I have been contacted many times by relatives wanting to find a home for their loved one’s logbook or decorations as they felt that the following generations no longer felt that connection with history. One could feel the desperation as they sought to find a home for them before they were lost. Over the years, as terrible as it is to contemplate, some were landfilled. Many were laid out at a garage sale; many more were mishandled and damaged beyond repair. Then came eBay.

With the advent of eBay, things that once were considered priceless and beyond the dirtiness of dollars, found an intrinsic monetary value. Now a great grandchild could sell off those dusty, old and meaningless medals to a collector and with the money, buy some object of their materialistic desire… on eBay of course! These objects do not, in and of themselves, have the ability to speak to their meaning and greatness. A young thirty-something in his new “Beemer” doesn’t give a rat’s ass about “all that crap” in the basement, not because he is self-absorbed or ignorant (though this is possible), but rather they have never been informed of the greatness that lies within the ribbon and metal and old photographs. If it means nothing to them, but something to a collector, then why not sell it off and buy something that does mean something… like a new 3D television.

Just this minute I went to eBay to find some numbers. There is a whole massive category dedicated to “militaria”. I simply clicked on the search window without asking for anything in particular. Today, 17 March 2015, there were 710,383 items for sale of military heritage. A good percentage was reproductions, but there was at least half a million medals, photographs, collections, uniforms and military equipment items for sale.

The beauty of eBay is that it connects these artifacts with collectors, people who actually do care about them. I have no issue with most collectors for many understand the emotional and historical nature of these artifacts, and are simply interested in keeping them safe. I have no issue with younger generations who place no familial value whatsoever on these artifacts, for they were not taught or brought up in a family that valued such heritage.

What truly saddened me are two things. Firstly, the monetary value reached by collectors is established by and is dependent on the rarity of the campaign medals and the level and number of the decorations. The medals of Flight Sergeant Smith with a Distinguished Service Medal and Burma Star might be valued less than a Wing Commander Jones with a DFC and Africa Star. Battle of Britain and Malta provenance might bring a premium over and above a Bomber Command member’s medals. It distresses me to see a scale of value put on men and women who were simply carrying out the orders they were given. A man, who accepted his fate as an instructor pilot and carried out his duties with professionalism and devotion to duty is somehow, through the filter of money, considered to have contributed less. It makes me sad, for all service has the same value, if not the same story.

Secondly, and this is the most serious problem, collections of photographs, mementos and medals are often broken up and their components sold off individually in order to wring greater profit. Recently, my good friend Richard Mallory Allnutt, a gifted writer, photographer and extremely knowledgeable historian and advocate of cherishing our heritage drew my attention to seven black and white postcards that were for sale individually on eBay. The postcards were originally a set of seven, for each was numbered. The postcards were made aboard HMS Victorious and depicted seven photographs taken aboard the Royal Navy aircraft carrier during her search for and her attack on the German battleship Bismarck. The cards were likely created in the photographic section aboard the carrier and offered to crew members as mementos of the action—each having been approved by the Navy censor aboard. Each postcard had notations on the reverse side describing the scene on the front that were clearly written by the hand of someone who had been aboard during the Bismarck campaign. The images depicted scenes of a ship readying for action and then finding and engaging the enemy.

If my memory serves me well, they were offered up for sale at around £30 (pounds sterling). Within days, they had disappeared from view on eBay, purchased likely by a collector of military mementos or possibly even specializing in such things as Royal Navy aircraft carriers, military postcards or even as specific as all things Victorious. The problem was, however, that the last postcard of the series was not sold and was still available on eBay.

This card showed a simple view of the Chapel of Saint Christopher aboard HMS Victorious. Of all the cards it was the only one which did not depict any of the action, did not speak of the Bismarck nor show any military hardware. I believe (and I could be just guessing) that the buyer saw this as less valuable and in doing so broke up the set by simply purchasing the ones he desired. But here’s the thing. I believe that this postcard was perhaps one of the most telling of the set—alluding to the stresses and emotions of those “in peril on the sea.” It is clear from the annotation on the reverse side that the writer sought solace there throughout the action. In many ways, this tells us how some sailors dealt with their fears and mortality, how they found the strength to face a possible toe-to-toe battle with a fearsome enemy. History is only complete if all of it is embraced. To cut away parts that are less desirable is to remove the nuance and depth. Sad.

Related Stories

Click on image

The first in the series of eight postcards. The image featured on the front can be found in the photo archive of the Imperial War Museum with the attached caption: HMS Aurora, escorting Victorious in dash to get within striking distance of Bismarck, finds difficulty in keeping up in poor weather. The back side of the card carries a point form description of the front from a man who, from the various cards, appears to have been on board Victorious. The inscription reads: Pursuit of Bismark. [Sic – The writer spells the ship’s name incorrectly throughout] 1) Commencement of the chase. 2) The wake of “Victorious” denotes tremendous speed at which she was travelling. 3) A heavy sea bridge – High, breaking over escorting cruiser. The bows of which are just emerging thro’ the spray, like the head and shoulders of a man. 4) Note in right half of photo, on horizon-line two of our destroyers screening “Victorious”. Although Aurora looks small in this image, she was in fact a 6,600 ton light cruiser. Photo: Imperial War Museum

In this dramatic shot of the bows of Victorious, we see the raw Arctic and North Atlantic weather that hampered making contact with the German battleship. The flight deck of Victorious is some 50 feet above the water, so she is diving deep in a trough to take water over her deck. The inscription on the card’s back reads: Pursuit of Bismark 1) “Victorious” in heavy seas off “Iceland”. 2) Receding plume-like spray of a wave, in front and on both sides of bows. 3) Measure off one inch in front of the ship, and you will have the formation of another heavy-wave, about to break over the flight-deck. To the right we see one of her long range radio antennae, normally lowered to horizontal for flying operations. Photo: Admiralty Official Collection, Imperial War Museum

Although this photograph from the Imperial War Museum’s Admiralty Official Collection seems like simply another Swordfish taking off from Victorious, it is in fact the first Swordfish to take off in an attempt to find and attack Bismarck. The three men in this “Stringbag” are at the very pointy end of a massive operation involving dozens of Royal Navy ships of the line. It would be these three men who would make first contact with the German raider. The notations on the back give clear indication that the writer was on board, for some of these details would not be available to the general public after the fact. Pursuit of Bismark 1) The first plane to attack, rising off the flight-deck. 2) The ship was brought up to the wind, and made “steady”. 3) So strong was the wind, ship’s speed was reduced for steadying-purposes. Normal speed and lifting force of wind required for such a take off = 40 miles per hour.

In one of the hardest to read, yet immensely dramatic, photos in the collection and of the Bismarck pursuit, a Fairey Swordfish observer of the Fleet Air Arm photographs Bismarck, the pride of the German Navy, steaming in heavy seas beneath a heavy wet sky on 24 May 1941. We have added the arrow to better spot the obscure form of Bismarck. The postcard offers the same view but closer in to the German battleship. The inscription on the back by the author who begins to show a love of the exclamation mark, reads: Pursuit of Bismark 1) In the gathering darkness of an artic-night [sic]. Bismark! Was sighted! 2) You can see her in the centre of the picture. 3) She is at the end of an arc like evading turn. This photo was taken I believe, by the first plane off. to attack. And register a hit. Looking at this image one can only imagine the powerful sense of excitement and dread going through the minds of the 825 Squadron Swordfish’s three man crew. One can feel the frigid Arctic air, the dampness; hear the roar of the Pegasus engine and the wind in the wires, feel the threat of the mighty battleship and the deep cold waters upon which she ploughs her way home—a home she would never see. Photo: Admiralty Official Collection, Imperial War Museum

The postcard at lower left depicts the smoke rising from Bismarck when she was struck by a torpedo from one of Victorious’ Swordfish. While I could not find that exact photo on the Imperial War Museum’s online photo records, I did find a similar one from an article on the UK’s Daily Mail Online newspaper dated 12 December 2012. Coincidentally the article was about the sale, at auction, of a similar set of postcards from another Victorious crew member’s collection. These cards all had similar inscriptions on the back, but the postcard of the torpedo strike smoke on the horizon had a photo taken a few moments later (above). A surviving Bismarck crew member describes the torpedoing; “They came in flying low over the water, launched their torpedoes and zoomed away. Flak was pouring from every gun barrel but didn’t seem to hit them. The first torpedo hissed past 150 yards in front of the Bismarck’s bow. The second did the same and the third. Helmsman Hansen was operating the press buttons of the steering gear as, time and time again, the Bismarck manoeuvred out of danger. She evaded a fifth and then a sixth, when yet another torpedo darted straight towards the ship. A few seconds later a tremendous shudder ran through the hull and a towering column of water rose at Bismarck’s side. The nickel-chrome-steel armor plate of her ship’s side survived the attack ...” This attack put Bismarck down at her bow and had slowed her speed. Days later, another Swordfish would cripple her rudders with another torpedo, allowing capital ships of the Royal Navy to catch her up and despatch her. The inscription on the back of the postcard reads: Attack on Bismark! “Element of surprise!” “The best method of attack.” 1) The first torpedoe [sic]. Well and truly laid. Finds its mark. On the Bismark. 2) Note the smoke of explosion. 3) An inch to right of Bismark, is I think, the plane escaping “low over the sea”. Photo: Royal Navy

The postcard at lower left depicts the smoke rising from Bismarck when she was struck by a torpedo from one of Victorious’ Swordfish. While I could not find that exact photo on the Imperial War Museum’s online photo records, I did find a similar one from an article on the UK’s Daily Mail Online newspaper dated 12 December 2012. Coincidentally the article was about the sale, at auction, of a similar set of postcards from another Victorious crew member’s collection. These cards all had similar inscriptions on the back, but the postcard of the torpedo strike smoke on the horizon had a photo taken a few moments later (above). A surviving Bismarck crew member describes the torpedoing; “They came in flying low over the water, launched their torpedoes and zoomed away. Flak was pouring from every gun barrel but didn’t seem to hit them. The first torpedo hissed past 150 yards in front of the Bismarck’s bow. The second did the same and the third. Helmsman Hansen was operating the press buttons of the steering gear as, time and time again, the Bismarck manoeuvred out of danger. She evaded a fifth and then a sixth, when yet another torpedo darted straight towards the ship. A few seconds later a tremendous shudder ran through the hull and a towering column of water rose at Bismarck’s side. The nickel-chrome-steel armor plate of her ship’s side survived the attack ...” This attack put Bismarck down at her bow and had slowed her speed. Days later, another Swordfish would cripple her rudders with another torpedo, allowing capital ships of the Royal Navy to catch her up and despatch her. The inscription on the back of the postcard reads: Attack on Bismark! “Element of surprise!” “The best method of attack.” 1) The first torpedoe [sic]. Well and truly laid. Finds its mark. On the Bismark. 2) Note the smoke of explosion. 3) An inch to right of Bismark, is I think, the plane escaping “low over the sea”. Photo: Royal Navy

When I checked the progress of the sale of the cards on eBay, I was saddened to see that all but the last card were sold, likely to the same bidder as they disappeared at the same time. I was sad, because it was fairly obvious that the buyer did not care to purchase that last card as it had no military hardware portrayed, no action, no Royal Navy ship working her way to and from battle. In fact, the last postcard, a shot of the chapel aboard Victorious, looks as if it was taken in a land-based building. Only the ship’s structure, piping and emergency lights give it away. My guess is that the buyer did not think this was as important historically as the others. It breaks my heart that this may have happened, as for me, this shot has as much immediacy and importance historically as the rest, largely because of the inscription on the other side: The Church of “St Christopher”. H.M.S. “Victorious”. “Wherein I sometimes dwell.” Padre: - The Rev; Dixon. M.A. R.N. Here clearly, the writer expresses with his honest Heart of Oak, that old adage: There are no atheists in a foxhole. That the writer cared enough to include it in his 7-card memoir of the Bismarck adventure is proof enough that it belongs in the set, yet the buyer did not purchase it. And so historical mementos become a sort of emotional diaspora, scattered on the winds of time and whim, broken down to component pieces, to be sold off according to a scale of value. Photo: Imperial War Museum

But it’s not all sad. Sometimes family members can be reunited with the mementos of a long lost relative. Recently, Englishman Phil Grimwade was searching the internet for information and historical reference to his great uncle Lieutenant Albert “Tiddles” Brown, a Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm Corsair pilot who died when his aircraft was brought down by flak whilst strafing the Japanese-held oil refineries at Palembang, Sumatra. To his utter surprise and delight, he came upon Brown’s service medals for sale on eBay.

Brown’s widow would have been the recipient of these medals and when she remarried and moved to Canada, all connection was lost by the family. It was likely that her children (a son who never met his father and perhaps others with no bloodline leading to Brown), simply did not see the family value in them. Likely, as new generations came any emotional connection to them had been broken. Grimwade was able to purchase them and bring them home to the family of Albert Brown. Thanks to Grimwade’s interest in his great uncle who was held in great esteem, some of Albert’s mementos are back where they truly belong—cherished, revered, well cared for.

And here’s the rub. Without an online auction service like eBay it is very unlikely that Grimwade would ever have been able to find the medals and without the internet, to find any information about Brown for that matter. In fact, his search brought him to find a couple of articles on the Vintage Wings of Canada website that made mention of “Tiddles” Brown.

I ask you to imagine that an ancestor was a Royal Navy officer aboard HMS Victory with Nelson at Trafalgar, or a great grandfather who fought his way up Vimy Ridge with the Canadian Army or perhaps a great uncle in the United States Marines who fought a merciless battle against the suicidal Japanese at Iwo Jima. Imagine how proud you would be. But then imagine how these powerful stories would flow with familial blood and come to life if you held in your hands a tricorn naval officer’s hat once doffed in “huzzahs” for Nelson at Trafalgar, a bayonet that an ancestor had affixed to his rifle as he followed a rolling barrage up Vimy ridge. These stories are what families are made of. These ancestors and relatives are the things that make you great, that colour our lives and bring meaning to our world. They are where we come from. They are our blood.

I am not one to quote song and lyric, but truthfully in this case the best words about all this and our duty to remember and teach our children come from a song—Teach Your Children by Crosby, Stills & Nash. I leave you with them now...

You, who are on the road, must have a code that you can live by.

And so, become yourself, because the past is just a good bye.

Teach your children well, their father’s hell did slowly go by,

And feed them on your dreams, the one they picked, the one you’ll know by.

Don’t you ever ask them why, if they told you, you would cry,

So just look at them and sigh, and know they love you.

And you, of tender years, can’t know the fears that your elders grew by,

And so, please help them with your youth, they seek the truth before they can die.

Teach your parents well, their children’s hell will slowly go by,

And feed them on your dreams, the one they picked, the one you’ll know by.

Don’t you ever ask them why, if they told you, you would cry,

So just look at them and sigh, and know they love you.

Lieutenant Albert “Tiddles” Brown was a Fleet Air Arm (FAA) Corsair pilot flying from the Royal Navy’s aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious during the Second World War. When Brown’s great nephew, Phil Grimwade, spoke recently of his uncle, he said “Albert has always been an enigmatic character for us, my late Grandfather would sometimes speak about their childhood but any mention of his service in the FAA was generally discouraged and his death was never spoken about. We think that Albert’s death affected him quite deeply, and his of course was the generation that ‘didn’t talk about things’. Personally I think it’s really important to share this information before it is lost—the WWII veterans are dwindling now—so have taken it upon myself to find out as much as I can.” Grimwade went searching for information on the internet, he found not much information but was astonished and delighted to find his Great Uncle’s war service medals for sale on eBay! After Brown was killed in the line of duty whilst strafing the Japanese-held oil refineries at Palembang, Sumatra, his service medals were sent posthumously to his widow. Brown’s widow and young son left the UK after the war and moved to Canada along with his medals.

When Phil Grimwade entered Lieutenant Albert “Tiddles” Brown’s name in the Google search window, he was both shocked and delighted to find that the war service medals of his long-lost great uncle were up for sale on eBay. It was sad to realize that Brown’s widow’s second family had not truly treasured these priceless mementos, but Grimwade jumped at the chance to bring them back home to Brown’s family, where his memory was so greatly respected. Clockwise from upper left: The War Medal 1939–1945: a British medal awarded to those who had served in the Armed Forces or Merchant Navy full-time for at least 28 days between 3 September 1939 and 2 September 1945. It would be paired with the ribbon at right above (Red, white and blue stripes). The Burma Star: awarded for service in the Burma Campaign between 11 December 1941 to 2 September 1945. It was also awarded for certain service (specified by dates) such as China, Hong Kong and in the case of “Tiddles” Brown, Sumatra, where he was killed. Because Brown was a recipient of the Burma Star, he could not receive a Pacific Star. Instead, he was awarded the equivalent: The Pacific Clasp, the small horizontal bar which was to be affixed to the ribbon of the Burma Star. The Burma Star ribbon, reputed to have been designed by King George VI himself, is the one second from left above (The broad dark blue stripes represent British forces, the red stripe Commonwealth forces, and the bright orange stripes represent the sun). The 1939–1945 Star: was a campaign medal issued to servicemen and women of the British Commonwealth for any period of operational service overseas between 3 September 1939 and 8 May 1945 (2 September 1945 in the Far East). It required a minimum of 180 days afloat for Navy personnel such as Brown. It was suspended from the dark blue, red and light blue ribbon second from the right above. Finally, at bottom, The Atlantic Star and its gorgeous ribbon (upper left) which was awarded for no less than six months afloat in the Atlantic or Home Waters. The 1939–1945 Star must have been awarded BEFORE commencement of qualification for the Atlantic Star. The beautiful ribbon from which the Atlantic Star hung was also said to have been designed by George VI and the gradient watered-blue, white and sea-green stripes denoted the colours of the Atlantic Ocean. It is telling to note that the medals themselves came in their original wax-paper sleeves and that the ribbons had never been attached, nor the Pacific Clasp sewn to the 1939–1945 Star. While Brown’s medals were in pristine condition, it was clear that they had rarely seen the light of day. Photo: Phil Grimwade

A group photograph from the Second World War shows 30 pilots of the 15th Fighter Wing of the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm at Surabaya with Albert Brown (second from right in middle row). The pilots in the Wing group photo are as follows: Back row: Harry Whelpton, Reg Shaw, Matt Barbour, Tony Graham-Cann, Jock Fullerton, R. Quigg, Steve Starkey, Pete Richardson (wing observer), Jake Millard, Eric Rogers, Hugh MacLaren, Colin Facer, Stan Buchan, Gord Aitken, Hugh “Moe” Pawson; Middle row, seated: S. Seebeck, Johnny Baker, Alan Booth, Bosh Munnock, Norm Hanson, Mike Tritton (the unit’s new commander), Bud Sutton, Percy Cole, Don Hadman, Albert “Tiddles” Brown, Les Retallick; Front row, sitting on deck: Neil Brynildsen, Jimmy Clark, Mike Ritchie, Brian Guy. Photo via Pawson Family Archive

A close-up of the previous photo reveals Albert Brown second from right on middle, resplendent in his Navy whites and tropical shorts. Photo via Pawson Family Archive