NAVY BLUE FIGHTER PILOT — Episode Two

Having learned the skills of the carrier pilot, and plied his trade in the icy northern seas, young Don Sheppard now takes his hard earned experience to the swelter of the Indian Ocean, fighting the desperate Japanese in their resource outposts. Presenting Episode Two of Navy Blue Fighter Pilot, by Michael Whitby – a three-part series on the Second World War career of Corsair ace Lieutenant Donald Sheppard. To read Episode One, click here.

In many respects the initial experiences of Victorious’ fighter wing with the Royal Navy’s Eastern Fleet was a matter of one step forward, two steps back. They arrived brimming with confidence from their success with the Home Fleet, but after a few months in the new theatre concerns arose as to whether they were truly prepared to attack the strongly defended targets on the strike program. As much as anything, the young aviators became stale, perhaps even comfortable, but other factors contributed to the problem. Since early 1942, the Indian Ocean had been a strategic backwater—the Eastern Fleet had not conducted a major offensive operation since the invasion of Madagascar in May 1942—and the steady bleeding of men and resources to more decisive theatres meant the fleet suffered in terms of training and cohesion. Moreover, aircraft carriers had been stationed there only intermittently, therefore the air organization was untested and immature. These shortcomings were widely recognized, and in May 1944, the outgoing commander-in-chief, Admiral Sir James Somerville, told his successor that the fleet “was most definitely a Ford not a Rolls-Royce outfit.”[i] So the need to learn—or in Victorious’ case, re-learn—pervaded the entire fleet.

The demise of Italy and other victories in the European theatre finally allowed the Royal Navy to reinforce its emaciated forces in the Indian Ocean. In late January 1944 HMS Illustrious arrived at the Eastern Fleet’s main base of Trincomalee, Ceylon armed with the Barracudas of the 21st TBR Wing and the Corsairs of 15th Naval Fighter Wing. The Admiralty had originally proposed to send Illustrious via the Panama Canal so that she could work alongside the USN’s Fast Carrier force—the acknowledged masters of naval aviation—for four months before proceeding to the Indian Ocean, but the Americans wanted to exert immediate pressure in the Far East to tie down Japanese forces that might otherwise be transferred into the Pacific. They agreed to loan USS Saratoga to the Eastern Fleet, and in April and May the two carriers joined to launch out raids on Sabang and Surabaya. Both strikes met success and were carried out with minimal losses. As important, the British absorbed many lessons from the American ‘brown shoe’ aviators on the planning and execution of carrier operations. The C-in-C of the Eastern Fleet “pronounced Saratoga a bloody good and effective ship”, and a standard for British carriers to model. After the American carrier left, Illustrious completed a couple of minor operations with the escort carrier HMS Atheling, still commanded by Captain Ian Agnew, RCN, but the latter’s limited capability proved too restrictive to be effective.[ii]

When Victorious arrived in Ceylon on 5 July 1944 in company with her sister ship Indomitable, Sheppard entered a world completely different from that he had left behind. Steamy tropical heat replaced bitter chill; lush equatorial vegetation carpeted the landscape instead of barren rock; elephants, not vehicles, towed aircraft about; and venomous snakes joined insects in their bedding. The contrast could not have been sharper. However, the fundamental purpose remained the same, and Sheppard went back to work, flying eight hours in routine training sorties before embarking on his first operation with the Eastern Fleet.

The young naval aviators who found themselves flying out of Ceylon would have understood Rudyard Kipling’s sentiment, “Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.” Life there was an eye opener, and chances are they had never before laid eyes on an elephant, let alone encounter one at work towing an aircraft around their airfield. Photo: Imperial War Museum

As it transpired, Operation CRIMSON turned out to be more of a big-ship gunnery exercise than an air strike. The target was Sabang, and four battleships, seven cruisers and ten destroyers joined Victorious and Illustrious. At first light on 25 July, Corsairs attacked three airfields, destroying four aircraft on the ground. Flak was heavy, and one Corsair was forced to ditch in the ocean but the pilot was rescued. With the air threat reduced, the bombardment forces moved in to shell targets around the harbour—Sub-Lieutenant ‘Pappy’ MacLeod, RCNVR, flying overhead as No. 3 to Lieutenant-Commander Dick Turnbull, leader of the 47th Naval Fighter Wing, thought 90 per cent of the shells missed their targets and exploded harmlessly in the harbour.[iii] On completion of the shoot the Fleet withdrew westward at high speed, and after rendezvousing with the carriers, headed for home. Sheppard flew a Combat Air Patrol (CAP) mission early in the day but had already landed when nine enemy aircraft approached the fleet just before sunset. They were engaged by 13 fighters, and three of the Japanese fighters were shot down. The remainder of CRIMSON was uneventful and the Fleet entered Trincomalee on 27 July. An Admiralty narrative crowed, “July 25, 1944, was a notable date in the history of naval operations in the Far East, for it was then that the Eastern Fleet, for the first time since it turned to the offensive, brought the guns of its ships into action against Japanese shore defences.” Perhaps, but the big guns of the fleet would play a minor role in the operations to come, and naval aviation would be the most decisive force in the theatre.[iv]

Sheppard flew CAP many times over the next ten months, so it is worth describing the nature of the missions. CAPs were carried out by all three fighter types then flying with the fleet, but when strikes were under way the duty often fell to the shorter-ranged Supermarine Seafires which, unlike Corsairs and Hellcats, lacked the legs to accompany strike aircraft. Circumstances varied but typically a couple of flights of four fighters were airborne at high, medium and low altitudes, situated so as to provide a height advantage against incoming raiders—for example, the high level CAP flew at between 20 and 30 thousand feet. Corsairs and Hellcats were usually up for three to four hours—Seafires only managed one-and-a-half to two hours, which meant the fleet had to turn into the wind more often to launch and recover aircraft—and flights flew in loose formation so as to ease strain and provide flexibility. Pilots normally went on oxygen when they flew above 12,000 feet. Fighter direction teams in the carriers controlled the CAP—sometimes cruisers and battleships also tried their hand—and vectored them onto radar contacts. The RN had honed this to a fine art, but it is important to emphasise that radar was still an inconsistent tool, leading to many missed or bogus interceptions. Depending on enemy activity, CAPs were normally completely uneventful. Sub-Lieutenant Johnny Maybank RNZNVR, a New Zealander who flew Corsairs off Illustrious and Victorious, found it “dead boring.” Yet, because “you never knew what was going to happen”, one always had to stay alert which added at least some “element of excitement.”[v]

“A fighter born out of desperation”, wrote aviation historian Tony Holmes of the Supermarine Seafire, the Spitfire that went to sea. Seafire squadrons arrived in the Eastern theatre with HMS Indomitable, and later HMS Indefatigable. Despite their elegant lines and revered air-fighting capability, Seafires had significant weaknesses as a naval fighter, leading Rear-Admiral Vian to conclude they were “unsuitable for ocean warfare.” Although effective in the low- and mid-level CAP roles, their limited endurance and poor decking-landing characteristics disrupted the flow of air operations and increased the burden on Corsairs and Hellcats. In operations off Japan later in the summer of 1945, the adoption of drop tanks from American P-40 Warhawks improved their endurance significantly. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Related Stories

Click on image

After the fleet returned from CRIMSON a personnel change occurred that had a significant impact on Sheppard’s future. Lieutenant-Commander Turnbull, leader of the 47th Naval Fighter Wing since its inception, was sent ashore for a rest after three years of operational flying.[vi] The pilots of 1834 and 1836 Squadrons were fortunate in his replacement since Major R.C. Hay, Royal Marines, was one of the great fighter leaders of the Second World War. An opinionated colourful Scot, Ronnie Hay had earned his fighter wings shortly after the outbreak of war, and had fought in Norway, Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain, and over the Malta convoys. He survived the sinking of HMS Ark Royal in November 1941, and after training in Army Co-operation duties, led Victorious’ 809 Squadron in Operation TORCH. He then took the RAF Wing Leaders Course, followed by a stint in a staff job where he helped draft the manual on Naval Air Warfare. In late 1943 he arrived in Ceylon to prepare the fighter training facilities for the expansion of the Eastern Fleet, but in May 1944 he requested a return to operations, admitting “he was after more gongs and more rank.” After years facing heavy odds in less-capable fighters, Hay was happy to finally engage an enemy from a superior position in a Corsair. “It was the first time in the whole war I was in total command in the air”, he recalled, “No airplane could touch me. I could out-climb, out-fly…probably out-manoeuvre and certainly out-dive all the Japanese.”[vii]

A number of Royal Marines saw distinguished service with the Fleet Air Arm in the Second World War, and Lieutenant-Colonel ‘Ronnie’ Hay was amongst the most illustrious. He saw action in virtually every theatre of the war, early on against terrible odds, and finished with a DSO, DSC and Bar, and an estimated four victories with nine shared (his original logbook went down with HMS Ark Royal, preventing a precise total). A skilled, inspirational and outspoken officer, Hay’s leadership and commitment to training were instrumental to the success of the 47th Naval Fighter Wing and Don Sheppard. Photo: clanhay.org

When leading the 47th NFW, Hay, soon promoted Lieutenant-Colonel, followed RAF practice and flew in a designated Wing Leader’s flight at the head of his squadrons. Because he was prone to mix it up in combat, flying with him was viewed as somewhat hazardous. A naval message in 1834 Squadron’s line book before one mission explained that two pilots were expected to be unable to fly as scheduled due to illness. One wag underlined the portion “2 will be sick” and drew an arrow to the margin where he scrawled, “Flying with the Colonel, no doubt!!”[viii] As it was, Sheppard flew with Hay a number of times, and met his best success in aerial combat at his wingtip.

The two squadron leaders that commanded 1836 under Hay were not his equal as fighter leaders, but they embodied a spirit of courage and professionalism that inspired pilots like Sheppard. Lieutenant-Commander Chris Tomkinson joined the RNVR after graduating in History from Oxford University. Flying Martlets with 881 Squadron in Illustrious, he shot down two enemy fighters during the invasion of Madagascar before becoming 1836’s first CO in August 1943. He was awarded a Mention in Dispatches (MID) after leading the squadron through the Norwegian operations, and the citation explains the effectiveness of his leadership: “By his unremitting zeal as a Squadron Commander he has trained his pilots to a high standard and has achieved an unusually high state of aircraft serviceability for all recent operations.”[ix] Lieutenant-Commander James Edmundson, RN, assumed command of 1836 after Tomkinson’s death in March 1945. A regular force officer, Edmundson had served at sea in minesweepers before becoming a member, and later CO, of 899 Squadron, where he experienced the perilous task of flying Seafires off small escort carriers. Edmundson went ashore as a flying instructor but returned to operations in October 1944. He, too, was ultimately killed in action.

Ronnie Hay parades Corsairs of the 6th Naval Fighter Wing over Colombo, Ceylon in May 1944. Cohesive formation flying was an essential element of the escort role often carried out by FAA fighters, and Hay was relentless in pushing his pilots towards excellence in that area. Hay assumed command of Victorious’ 47th Naval Fighter Wing in August 1944. Photo: Tony Holmes and Osprey Publishing

Tomkinson and Edmundson’s careers had followed typical wartime patterns; what sets them apart from the norm was that both volunteered to continue operational flying when they had valid reasons to withdraw. Tomkinson suffered from a serious kidney malady, and medical officers recommended that he not accompany 1836 to the Far East because of the harmful effect the climate might have on his health, however, he refused to abandon his pilots. Edmundson, who had seen 899 Squadron decimated by accidents in the summer of 1944, was safely ensconced in a comfortable training billet in Ceylon—most likely for a rest due to ‘twitch’—but he stepped forward as an emergency replacement when 1836 ran short of pilots due to illness, and then offered to remain with the squadron.[x] Although Sheppard and other pilots did not always agree with the tactics Tomkinson and Edmundson directed them to follow, they had great respect for their character.

Hay first led the 47th NFW into action on 24 August 1944 when Victorious and Indomitable struck targets at Padang, Sumatra. Things started badly when ‘Pappy’ MacLeod’s Corsair abruptly lost power during his launch from Victorious and stalled into the sea—after nearly being run down by a battleship and a cruiser, a destroyer finally picked him up.[xi] Sheppard and 1836 formed part of the escort for a ‘beehive’ of 20 Barracudas that attacked cement works at Indrarung. After the mission he gleefully recounted “Caught them with their kimonos up—pasted target.” 1834’s Corsairs hit targets at Emmahaven, where Sub-Lieutenant Thomas Cutler, RNVR, crashed into the sea after being hit by flak. Tomkinson had a frustrating mission. His generator burned out on the way to the target, and he “was thus left with no R/T, beacon etc., and with the knowledge that one short burst was the best that I could expect from the guns.” Instead of turning back he carried on to the target but found himself alone on the way back to the carriers: “I was flying parallel to the shore about 500 ft. and 5 miles off shore. As I looked to my right to make the turn out to sea I saw a Mitsubishi 96 [Claude] parallel to me and about 500 ft. above. I hauled round and pulled up steeply and was able to fire a very short burst at about 250–300 yards before the guns stopped. I observed no results from this burst and as I was then unable to call others to the scene or do anything but ram I left for home at 280 knots on the deck.”[xii]

Corsairs form up in the distance as a Fairey Barracuda trundles off HMS Formidable. The ungainly Barracuda had a number of weaknesses, but its relatively short range made it unsuitable for the Eastern Fleet’s strikes against the oil refineries on Sumatra. Due to their longer legs and ability to get airborne after a short run, Corsairs typically launched ahead of TBRs. The plume of steam rising at the fore end of the flight deck was intended to give pilots an indication of the wind speed and direction. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Corsairs and Barracudas, returning aircrew and the deck landing party crowd the fore end of Illustrious’ flight deck after the strike on Port Blair in the Andaman Islands on 21 June 1944. Although seemingly serene, the image conveys some of the hectic nature of flight operations. As the return strike landed, the deck landing party had to move quickly to secure aircraft in the hangar below so as to leave room for the continuing recovery of aircraft. In this case a Barracuda is being sent down on the lift. Since returning aircraft may be damaged or their pilots wounded, as landing operations progressed those on deck kept a wary eye on the ongoing recoveries in case an aircraft jumped the barrier to interrupt their gathering with potentially devastating consequences. Photo: Fleet Air Arm Museum

The strikes were considered a success, but Hay expressed dissatisfaction in his report to Victorious’ CO, Captain Michael Denny:

The almost complete lack of opposition made the raid rather a ‘picnic’ and so the soundness of the air organisation used was not verified. I consider this most important since not only has nothing been learnt as a result of this operation but the younger pilots may develop a casual attitude to flying over this part of Japanese occupied territory which will certainly stand them in no stead when they are called upon to perform more hazardous operations. In this connection it is hoped that future operations will be against increasingly more important objectives which, because they may be more hotly defended, will train the younger and more inexperienced pilots, who are greatly in the majority, the art of waging war successfully under battle conditions.[xiii]

Things did not improve in that respect on the next operation, a strike against a railway repair and maintenance centre at Sigli on the northeast coast of Sumatra. Sheppard was assigned to fly CAP, but he did not miss out on any action since the attack was completely unopposed. Even without an appearance by the enemy, serious problems arose. Two Hellcats mistakenly shot up the British rescue submarine, the CAP had been launched without long-range tanks and had to cut short their sortie, the top cover abandoned the Barracudas to attack ground targets and poor station-keeping by the carriers caused landing patterns to overlap dangerously.[xiv] Along with these issues, Hay expressed concern with his pilots’ state of training, warning Denny, “at present I would be reluctant to lead No. 47 Fighter Wing on an escort or a sweep mission where it would be likely we should run into serious opposition from the air.” With attacks against major targets on the horizon, Hay proposed that the wing carry out at least 15 full-scale training sorties, otherwise, “against heavy air opposition I fear, that unless we can carry out, at any rate, a proportion of these fighter practices mentioned earlier, our casualties are likely to be serious.”[xv]

This series demonstrates why Corsairs routinely dumped their drop tanks before landing on. Returning from the strike on Sigli, Sumatra in August 1944, 1834 Squadron’s commanding officer, Lieutenant-Commander Noel Charlton, was unable to jettison his drop tank, which burst into flames after it scraped the deck when he landed on Victorious. Fast action by the firefighting party got Charlton out without injury, and the Corsair was repaired to fly again. Charlton was known as ‘Fearless Freddie’, likely due to a 1943 incident at Macrihanish, Scotland when he suffered burns pulling a pilot and observer from their Swordfish after it crashed and burst into flames. Photos: Imperial War Museum

Senior officers evidently shared Hay’s concerns and laid on a period of intensive training. From October through December 1944, interspersed by one major operation, Hay led his pilots through the most rigorous training regimen they had probably undertaken. 1834 Squadron focussed on fighter-bomber activity while Sheppard’s squadron concentrated on tactical reconnaissance, strike escort, fighter sweeps and air-to-air combat. Hay described a fighter sweep serial over Ceylon on 10 November:

A good rendezvous was effected over Puttalam with 12 Hellcats from HMS INDOMITABLE covered by 6 Corsairs from 47 Wing and a top cover consisting 12 Corsairs 1834 Squadron and 12 Corsairs 1836 Squadron. The sweep was made seawards over the Colombo-Katukurunda Area and was intercepted by 12 Spitfires. The exercise was considered a failure owing to lack of cohesion between the two squadrons. The Spitfires waded into the bottom squadron and the battle was nearly over before the two fighter cover squadrons intervened. The top squadron never made the Area at all and finished up at Nagombo 18 miles north, while the battle was on at Colombo. However another valuable lesson was learned: ie it is no good having large height intervals if you are thereby going to lose contact with the force you are supposed to cover.

Lessons were learned and re-learned and solutions implemented, and in an escort exercise a month later, 1836 performed their close escort role “most efficiently, keeping station correctly and making the job of the four intercepting Hellcats extremely difficult.” When the training period ended, Hay reported it had been “of first class value to both pilots and maintenance ratings…. An atmosphere of staleness which was plainly evident has now been eliminated.”[xvi] In mid-October the training program was interrupted, and no doubt given impetus, by a strike on the Nicobar Islands. The Fleet finally encountered tough opposition, but that was the intent. Operation MILLET was designed to coincide with American landings in the Philippines in hopes of tying down the Japanese forces in the theatre. To achieve this, the targets selected were those that might indicate preparation for a major amphibious assault, and instead of the usual speedy retirement after the initial strike, Indomitable and Victorious would linger in the area for three days. As one senior officer bragged to the press, “We are going right up to his back door. We shall ring the bell and sit on the doormat until someone comes.”[xvii]

Corsairs launching off a carrier during the raids on Japan in the summer of 1945. By this time the BPF had adopted overall “Glossy Dark Blue” paint scheme for all aircraft “manufactured in the USA”. The image gives some indication of the tightly orchestrated launch cycles utilized to get aircraft into the air quickly. Note that the deck handling party have removed the chocks from all aircraft; the two in the foreground are leaning on their brakes; while the third is just starting to roll; and the fourth climbs away. Photo: Fleet Air Arm Museum

Corsairs of the 47th Naval Fighter Wing ranged on Victorious’ flight deck. The absence of any Avengers or Barracudas seems noteworthy and suggests she may have been at sea on a training sortie. Certainly, the type—and lack—of dress of the sailors on deck, and the markings on the landing gear flaps, indicate it was taken in the Far East sometime in the autumn of 1944. Photo: Tony Holmes and Osprey Publishing

This time Sheppard got over the target. On 17 October, in the opening phase of MILLET, Tomkinson led 1836 on a strike against an airfield at Nancowry. Sheppard’s logbook described a successful attack: “More fun than that! Caught some Japs on runway and strafed them.” Later, however, he criticized Tomkinson’s decision to approach the target at fairly high altitude, instead of ensuring surprise by going in low. Sheppard returned to Victorious for CAP duties, but other Corsairs remained to hit targets of opportunity, and two, including one from 1836, fell to anti-aircraft fire. One went down after the pilot made a second run on a flak position. “Only one error was made”, Hay reported bluntly, “and this cost the pilot his life. It is considered it would be of value if this incident was promulgated as showing the inadvisability of returning to a hornet’s nest once it has been well stirred up.”[xviii] Barracudas and other Corsairs hit defence positions and sunk a small vessel in the harbour, and surface ships later moved into position to bombard various targets.

The tired-looking Corsair Mk II JT-422 flown by 1836’s Senior Pilot, Lieutenant W. Knight. Don Sheppard flew JT-422 on a ‘Pin Point’ navigation exercise on 27 October 1944, probably about the time this picture was taken. Note the recently introduced ‘T’ Wing designation has been informally chalked on the fuselage. Photo: Tony Holmes and Osprey Publishing

Besides their premium performance, Corsairs had other qualities that helped make them outstanding naval fighters. Unlike some contemporary British aircraft, they featured power-folding wings, which negated the need for deck hands to wrestle them folded, and thus enabled flight operations to be conducted more expeditiously. In this image a Corsair folds its wings while taxiing forward immediately after recovering onboard Victorious. Corsairs were also durable aircraft that could sustain serious damage. The image below shows the terrible damage suffered by a Corsair flown by 1834 Squadron’s Sub-Lieutenant Don Cameron after a collision with another Corsair during a training flight. Cameron and his aircraft survived a harrowing 140-knot landing. Unfortunately, the other Corsair had a wing completely sheered-off and spun in. The New Zealander Cameron was taken prisoner after being downed by flak attacking Miyara airfield on 9 May 1945. Taken prisoner, he survived the war. Photos: Imperial War Museum

This time the Fleet faced more serious opposition, but to his frustration Sheppard missed out. He was flying CAP over the bombardment force on 19 October, when the battle cruiser Renown’s radar detected a shadower. Unfortunately, her untried air controllers bungled the interception, and Sheppard later seethed “RENOWN takes charge and gives us bum vectors so we miss a sitter.” Shortly after he landed, Corsairs still aloft engaged a dozen Japanese aircraft shooting four down in “a vicious melee”, which only added to his annoyance. Edmundson, flying his first mission with 1836, claimed one fighter, and three more enemy aircraft were destroyed in a later engagement. Captain Denny expressed satisfaction with the operation, and was particularly pleased for his Corsair pilots: “As far as VICTORIOUS’ air group was concerned everything went according to plan and the opportunity provided a long-awaited opportunity for fighter combat for No. 47 Wing, who had to endure much flak in operations they have carried out, particularly in home waters, and no compensation by way of air fighting.” Vic’s fighter boys were finally blooded, and as an Admiralty staff study concluded, this “had a good effect on morale.”[xix]

Victorious steaming in placid tropical seas southwest of Ceylon on 8 October 1944 with a deck load of Corsairs. The carrier had just emerged from dry dock in Bombay to have her steering machinery repaired, and was working-up prior to Operation MILLET. That day Sheppard was conducting gun camera exercises from ashore. Photo: Sheppard papers

As Hay recognized, the aerial opposition in the Far East was not as daunting as the FAA had encountered in other theatres. Although any fighter can pose a dangerous threat in combat, the capability of the Japanese fighter force had seriously deteriorated by this point of the war. The 3rd Air Army or Hikoshidan defended Sumatra, which meant that Sheppard and his fellow aviators tangled with pilots of the Japanese army air service (JAAF) almost exclusively. High attrition and a dried-up training pipeline had whittled down their overall skill, and except for an ever-diminishing number of veterans, the majority were unseasoned novices with a fraction the flying time of pilots like Sheppard. Their aircraft also did not match up. JAAF fighter strength in the theatre mainly comprised the Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa and Ki-44 Shoki—‘Oscars’ and ‘Tojos’, respectively, to the Allies. Both were extremely nimble, but suffered from the weaknesses inherent in that generation of Japanese fighters: relatively light armament, limited armour protection and, in most cases, no self-sealing fuel tanks. As a Japanese aviation historian has concluded, by the summer of 1944, “the superiority of the average Allied airman was absolute, as was the quality of the aircraft he flew and the centralized control under which he operated.” Ronnie Hay agreed. Asked after the war to compare the JAAF’s Oscars and Tojos to the Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica fighters he had tangled with previously, Hay scoffed, “Oh please, you only had to look at a Japanese and it burst into flames—one squirt and they would blow up…. I was very pleased.”[xx]

Sheppard and his squadron mates returned to the training grind after MILLET. While they honed their skills—Sheppard flew 62 hours in various serials between MILLET and his next mission in early January 1945—important changes were made in the Fleet, some of which had a direct impact on the young Canadian. On 22 November 1944, Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, RN, hoisted the flag of Commander-in-Chief British Pacific Fleet (BPF) standing-up the organization Sheppard would fight under for the rest of the war.[xxi] Since Fraser commanded the BPF from ashore, he did not influence Sheppard’s activities to the extent of Rear-Admiral Sir Philip Vian, RN, who, that month, was appointed Flag Officer Aircraft Carriers BPF, with the responsibility of directing the day-to-day conduct of air operations. Vian came with a formidable reputation as a fighting sailor, but one with a difficult personality. Historian John Winton related, “the opinions of all who served with him can be summed up in one sentence: ‘By God he could be an awkward bastard.’ Yet he was universally admired and respected as the Navy’s greatest fighting admiral of the war.”[xxii] Vian was not a naval aviator by trade, but he had gained valuable experience commanding a force of escort carriers covering the assault on Salerno. Importantly, he was willing to accept advice from aviation specialists, at least those who earned his respect.

Hay was one such officer, and soon after taking over the carriers Vian appointed him to the new position of Air Coordinator for the BPF. Loosely based upon the RAF’s Master Bomber and the USN’s Air Group Commander, Vian thought the position would be necessary when three or more carriers operated in company with more than 100 aircraft aloft. As Air Co-ordinator, Hay directed the escort and strike leaders during raids, and assessed the effectiveness of attacks to ascertain if follow-up missions were required. These duties entailed Hay’s flight circling over the target area at about 5–8000 feet for the duration of a raid, which made it a magnet for enemy flak and fighters. During the training period Hay personally put Sheppard through his paces on at least one occasion, and the fact that he later joined the Air Co-ordinator’s flight meant he had earned his seal of approval.[xxiii]

The final change came in December when Grumman Avengers replaced Barracudas as the BPF’s TBR aircraft. The Barracuda had proved a major disappointment; most seriously its limited range meant that some important targets lay beyond its reach, and to shorten the distance to objectives they could reach, carriers sometimes had to move uncomfortably close to the enemy coast to launch strikes. In contrast, the Avenger was one of the most effective carrier strike aircraft of the war. A stable, sturdy platform popular with aircrew, Avengers could heft one 1,000-lb. or four 500-lb bombs to a range of 1,000 miles—or about 350 miles further than a Barracuda—at a cruising speed of about 175 mph. 849 Squadron with Avenger Mk IIs—the RN designation for the USN’s General Motors built TBM-1—joined Victorious on 19 December 1944. [xxiv] They carried out ten days of familiarization training that culminated in Exercise TILE, a dress rehearsal of the next strike, which involved fighters and Avengers from Victorious, Indomitable and the newly arrived Indefatigable. Hay was aloft as Air Co-ordinator and reported, “with the exception of the close cover… I consider that the strike was well carried out.” Eight RAF Spitfire Mk VIIIs provided the opposition, “and two managed to penetrate the close escort due to the high speed of their attack.” “But”, Hay countered, again betraying his scorn for the enemy, “I trust we shall not have Spitfire VIIIs against us on the real thing.”[xxv]

This profile depicts an Avenger Mk II of Victorious’ 849 Squadron. Formed in the USA in mid-1943, 849 operated in European waters until joining Victorious in December 1944, where it served until the end of the war. This aircraft displays well the camouflage and markings of the Eastern Fleet, and took part in Operations LENTIL and MERIDIAN against the refineries in Sumatra. Photo: Tony Holmes and Osprey Publishing.

In late December the BPF initiated Operation OUTFLANK, a series of strikes against oil refineries in Sumatra. This was the proverbial pot of gold at the end of the strike rainbow. Severing the flow of oil to the Japanese home islands was a critical strategic objective of the Allies, and the Sumatran refineries produced the majority of the aviation fuel required by the enemy. There was an important secondary objective. The BPF was destined for Pacific operations, and as historian David Hobbs has explained, the Americans needed to be convinced that the British were capable of achieving such missions before allowing them to operate alongside their own front line carrier forces. The first raid associated with OUTFLANK came on 20 December 1944 when Indomitable and Illustrious attacked Pangkalan Brandon, the furthest north of the refineries. Poor visibility hampered targeting and only modest results were achieved.[xxvi]

Operation LENTIL, a repeat attack against Pangkalan Brandon carried out on 4 January 1945, marked Don Sheppard’s coming out party as a top fighter pilot. The largest raid yet carried out in the theatre, LENTIL involved 92 aircraft from Victorious, Indomitable and Indefatigable. The launch from Victorious was “distinctly below par” due to untried personnel in the flight deck crews, low wind speed over the deck and Hay being forced to shift to another aircraft when his went u/s. The strike eventually formed up and headed to the target in extreme visibility and scattered clouds. They crossed the coast at 3,000 feet and, after climbing over the mountainous terrain, approached the target at 11,000 feet. “Up to this time”, Hay reported, “there was no indication the enemy was aware of our approach.” Fairey Firefly fighter-bombers from Indefatigable carried out a rocket attack to suppress flak, followed by the Avengers, whose “Attack was concentrated and the majority of the bombs were seen to fall on their targets.” As this transpired, Corsairs, including 1834’s, attacked a cluster of airfields some 30 miles to the south.[xxvii] Nonetheless, enemy fighters got airborne and began to wade in to the attack just as the Avengers finished their bomb runs.

The Fairey Firefly brought tremendous versatility to the Eastern Fleet and the BPF. Capable of operating as a strike aircraft armed with three-inch rockets or as a close escort, Fireflies were a popular, dependable aircraft, and far superior to earlier British naval aircraft designs. Photo: Imperial War Museum

A Firefly from HMS Indefatigable’s 1770 Squadron about to launch on Operation LENTIL on 4 January 1945. The three-inch rockets visible on the launch rails proved to be an effective weapon, although achieving accuracy was sometimes a challenge. In LENTIL RP-equipped Fireflies scored the first hits on the refinery complex at Pangkalen Brandan, and on MERIDIAN II on 29 January 1945 they tried to clear a path through barrage balloons with mixed results. Photo: Imperial War Museum

When escorting strike aircraft, fighters deployed in either Close Escort or Middle and Top Cover. Typically, the Close Escort comprised three flights of four aircraft flying on either flank and astern of the TBRs, the rear flight weaving astern with flexibility to respond to any threatened position. The Middle and Top Cover continually crossed above the formation out of phase so that no flank was left unguarded—their altitude varied as to the mission and the cloud cover.[xxviii] On LENTIL, Sheppard was flying Middle Cover with 14 Corsairs from 1836, probably leading a two-plane section. This was his first encounter with enemy aircraft so it is not surprising that it remained engraved in his memory:

In this particular case the Japanese fighters came vertically down through the fighter cover in an attempt to shoot down the bombers, so I saw fighters coming straight down at high speed and then going straight up at high speed (or so it seemed at the time). My first kill appeared immediately below me and as I rolled down to attack he attempted to evade me by rolling over on his back and pulling through. However about half-way through this maneuver I fired a burst at him from a relatively short range and he bailed out!! To this day I can’t be sure that he left the aircraft because he was hit or because he was merely frightened.

The victim was a Ki-43 Oscar, and Sheppard later reported the pilot appeared to be dead when he hit the sea. Climbing back to rejoin the strike, Sheppard “spotted another Oscar below me heading for his aerodrome at high speed. Since I had an altitude advantage I was able to dispatch him quite quickly before he regained the sanctuary of his aerodrome.”[xxix] In contrast to this matter-of-fact account, his logbook betrays the excitement of the moment: “Strike escort against oil plant at Pangkalan Brandon Sumatra - 3.20 hrs. - Best strike yet in Dutch East Indies!! Little flak. No casualties. 7 enemy a/c shot down in air and many more were damaged on ground. I got 2 Oscars and Dusty Rhodes 1.[xxx] Returned with bad oil leak and only one gallon left.” The bar in Victorious’ wardroom normally opened after missions—Ronnie Hay, for one, was a strong proponent of the therapeutic powers of measured amounts of alcohol for his young aviators—and there is little doubt that Sheppard and his fellow fighter pilots celebrated their success over gin.

A Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa or ‘Oscar’. This pretty, nimble fighter was extremely manoeuvrable at all altitudes but was out-gunned and out-performed by the more durable modern naval fighters equipping the Eastern Fleet. Don Sheppard shot down two Oscars and shared in the kill of a third in fighting over Sumatra in January 1945. Photo: Historum.com

A fully-loaded Avenger trundles up Victorious’ flight deck in December 1944 or January 1945. Although the carrier was equipped with an ‘accelerator’ or catapult, it was rarely used during the war—this Avenger has plenty of deck to work with but those that occasionally launched from near the head of the deck park faced a tougher challenge. Although the Avenger was a relatively large aircraft, pilots appreciated its sturdiness and performance, and even flew it successfully from much smaller escort carriers. Photo: Sheppard papers

Avengers about to wheel in for their bomb run on the Pangkalan Brandan refinery during LENTIL. Fireflies and other Avengers have already inflicted damage on their initial runs. Circling above the target in his role as Air Co-ordinator, Major Ronnie Hay observed “Attack was concentrated and the majority of the bombs were seen to fall on their targets.” Photo: MaritimeQuest.com

As Avenger and Corsair pilots mixed at Victorious’ bar, there was probably conversation—some of it likely heated—about the conduct of the fighter escort. Some fighter pilots, presumably including Sheppard, were criticized for chasing enemy fighters instead of remaining with their charges. In his after action report, an unhappy Hay accepted that the fighters, including Hellcats from Indomitable who abandoned their Avengers to strafe targets, “did a lot of damage during their momentary dereliction of duty but the consequences might not have been amusing. I cannot emphasize too strongly that no fighter must do other than his prescribed duty except on the instructions of the one man who is in charge.” Edmundson, who received praise for sticking with the Avengers, reflected on the issue from the mindset of young fighter pilots: “I feel that all pilots now realize that in their enthusiasm to destroy the enemy, they left the TBRs rather open to further attack the enemy might have launched.”, he observed, but “What always seems to happen is that someone sees a ‘bogey’, makes a hasty report and chases off followed by everyone else who is anywhere near. The fault is actually that it’s not even every month of the year that you see a Zero in the FAA so you can hardly blame a fighter pilot for making the most of his opportunities.” He added, somewhat defensively, “I think Avengers are a pleasure to Escort, and the more often we do it, the better protection they will get.”[xxxi] This escort dilemma had, of course, existed for as long as fighters had attended bombers—should they be tethered to them or released to roam aggressively?—and in Victorious and the rest of the BPF it remained the subject of debate.

Hay raised a far more controversial issue in his after action report. During the air battle, he “observed two enemy shot down and one of the pilots bailed out. It is submitted that all Japanese aviators who, after being shot down, have a chance of rejoining their own lines, should be destroyed. It is the treatment we expect from them and it is considered that a policy letter on this point should be circulated to all squadrons.”[xxxii] Firing on a defenseless pilot in his parachute would be considered a war crime by some, and is extremely unlikely that an order such as Hay proposed would be promulgated or even drafted—although it would almost certainly be the focus of chat amongst pilots. One, however, should be careful not to judge too harshly, and consider the context and prevailing atmosphere. Hay and his pilots well understood the barbaric treatment they could expect to receive if captured, and any thought of ‘gentlemanly’ conduct had long gone out the window amongst most Allied sailors, soldiers and airmen fighting in the Asian and Pacific theatres of war—Johnny Maybank recalled rumours “that the Japanese were pretty brutal and not taking prisoners.”[xxxiii] It would be easy to condemn Hay, but one cannot get into the cockpit to understand the attitude in play at the time. One must appreciate that each time aircrew approached enemy-held territory they accepted that a terrible fate may await them. As evidence of this, after the war Sheppard and his comrades were shocked to learn that nine aviators, including six from Victorious’ 849 Squadron, who had been captured during Operation MERIDIAN later in January, were brutally murdered by Japanese officers in July 1945.[xxxiv]

As after most successful operations, while Victorious returned to Ceylon after LENTIL Captain Denny submitted recommendations for honours and awards for those who had distinguished themselves. Awarding ‘gongs’ could be a delicate business with numerous factors at play, but he had succeeded in gaining recognition for Edmundson and Tomkinson after MILLET, and they received a Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) and Mention in Dispatches respectively. Denny now recommended Sheppard for his achievements in LENTIL. The official citation that accompanied Sheppard’s decoration was typically sparse, stating “For courage, skill, daring and devotion to duty whilst operating from H.M. Ships Victorious, Indomitable and Indefatigable in an attack on enemy oil refineries in the Far East (at Sumatra on 4th January 1945).” However, Denny’s original recommendation was more substantive:

This officer has shown the greatest keenness and determination to get to grips with the enemy. He has trained himself to a high standard of skill in the air and has made every effort to become a first class fighter pilot. He has worked with energy and success in improving the standard of armament maintenance in the Squadron. The results of his keenness were shown recently in Operation ‘LENTIL’, when he shot down two enemy fighters in his first aerial combat. Has taken part in 8 operations from Victorious.[xxxv]

A year after the war ended, Don Sheppard formally receives his Distinguished Service Cross from Rear-Admiral Cuthbert Taylor, RCN, in a ceremony on the flight deck of HMCS Warrior in Halifax harbour. He now wears the straight stripes of an officer of the regular force. He later admitted that flying in the postwar navy was not as enjoyable as during the war. Photo: Sheppard papers

The reference to armament maintenance stemmed from Sheppard’s secondary duty as 1836’s Armament Officer. In this capacity he worked closely with the squadron’s armament ratings, and the fact that Victorious was later lauded for the lack of gun failures in its Corsairs credits his efforts.[xxxvi] Sheppard obviously showed great promise, and even if one takes into account the grandiloquence that normally buttresses award recommendations, Denny’s language indicates he was highly thought of in Victorious. He convinced the Admiralty to that effect, and in March 1945 Sheppard learned he had been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

This superb profile by Mark Styling depicts Don Sheppard’s personal ‘cab’ for a good part of his operational career. All told, he flew Corsair II Ser. No. JT-410 some 42 times between August 1944 and January 1945, including on operations LENTIL and MERIDIANs I and II, and it was therefore the fighter he was flying for his first four victories. According to Styling, Lieutenant James Edmundson also flew this Corsair when he shot down a Japanese fighter on Operation MILLET. There is often confusion over the meaning of the various “distinguishing symbols” or markings, but these accurately reflect those promulgated under Confidential Admiralty Fleet Order 1901 issued in August 1944. ‘T’ represents the “standard Wing letter” assigned to the 47th Naval Fighter Wing; ‘8’ was one of the four designated “squadron figures” for operational fighter squadrons, in this case 1836; and ‘H’ was the “terminal letter” allocated by individual squadron commanders (any letter could be used except for ‘E’, ‘I’, ‘O’ or ‘T’). According to the regulation, these letters were to be painted in sky but that and their position relative to the roundel sometimes varied. Photo: Mark Styling

With LENTIL putting a modest dent in Japanese oil production, Fraser and Vian turned their attention to the main prize, the refinery complex at Palembang. There, located across from each other on the Palembang River, lay the Pladjoe and Soengei Gerong refineries, the largest oil producers in the Far East. The BPF was not the first to try to take them out. In August 1944, B-29 strategic bombers of the United States Army Air Force had staged through Ceylon from China to attack Palambang in one of the longest-ranged bombing raids of the war. Although the mining component of Operation BOOMERANG proved effective, the results of the bombing, conducted at night by radar, were disappointing. [xxxvii] Senior Allied planners realized that strategic bombers would have difficulty taking out the target, and the Americans requested the BPF attack the facility. This decision was no doubt influenced by the fact that the BPF would be in Palembang’s ‘neighbourhood’ on its way from Ceylon to its new base in Australia.

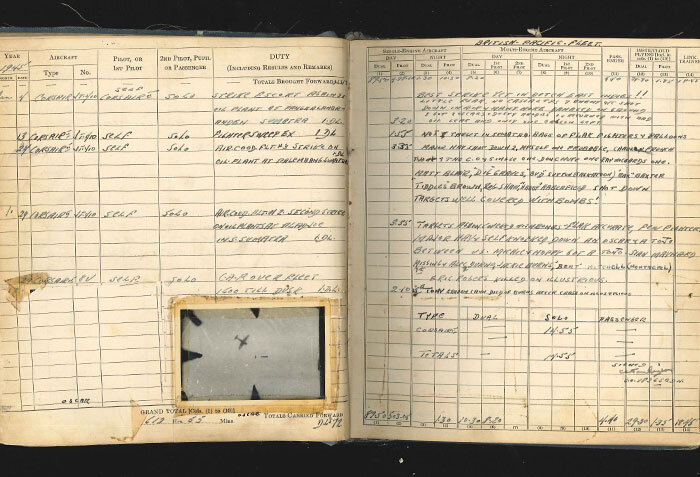

Don Sheppard’s logbook is a remarkable historical document. Unlike many other pilots he included some details of his missions, which makes it more like a personal diary. These images display his entries for January 1945 when he participated in Ops LENTIL and MERIDIAN, and shot down four enemy aircraft. The image of the enemy aircraft is presumably gun camera footage of one of the Ki-43 Oscars he shot down. Photo: Sheppard papers

The two strikes against Palambang—Operations MERIDIAN I and II—were the largest carried out by the Fleet Air Arm in the Second World War, and the first to involve four fleet carriers—one fighter pilot called MERIDIAN “the big one!” Vian originally intended to launch three strikes on the target, one against each refinery and a third to mop-up, but, ironically, his options were restricted by the limited amount of fuel carried by his replenishment ships. Since it would court disaster to attack from the Java Sea or the Straits of Malacca, the strike would be launched off the Indian Ocean coast of Sumatra, which entailed a long 150-mile flight over mountainous jungle, or the ‘ulu’ as aviators called it. Aircrew would then face the toughest defences they had yet encountered in the theatre. Intelligence briefings warned that dozens of flak positions protected the target, and one report warned of the possible presence of barrage balloons, although that was eventually dismissed. Aircrew were told to expect a “vigorous response from Japanese fighters”, and “With 50 Tojo available they should be able to give a good account of themselves but much will depend on how much warning they get and how good their individual pilots are.” Thirty Oscars, described as “operational training aircraft”, were also based nearby.[xxxviii] Briefings touched on all aspects of the mission. A Hellcat pilot with Indomitable’s 1839 Squadron recalled a flurry of preparation:

…for five days we attended briefing after briefing, learning everything by heart, such as the best way to get back to the West coast, the dates and places where we would be picked up by submarines etc., if we happened to be unlucky enough to be shot down. We were given practice interrogations of what to do and say if made a POW, which made one realise how easy it was to make a slip which would mean so much to the Jap. In our kit we carried revolvers, water bottles, hatchets, mirrors, razor blades, silk maps, energy pills, chewing gum, chocolate and twenty gold sovereigns for bribing our way back to the coast, and for being looked after, as well as many other oddments such as first aid outfits.[xxxix]

On 16 January 1945 Force 63, comprising Indomitable (flag), Victorious, Illustrious, Indefatigable and their screen departed Trincomalee. Rear-Admiral Vian had scheduled MERIDIAN I for 23 January but high winds and torrential rain forced a postponement. At 0415 on 24 January Sheppard and the other aircrew in Victorious gathered for breakfast in the wardroom before heading to a final briefing. The target of MERIDIAN I was Pladjoe, the largest of the two refineries at Palambang. Fifteen minutes prior to launch he climbed into his fighter. Hay’s Corsair was the first down the deck at 0620, and as his No. 3, Sheppard launched seconds later. They were part of the first wave of 43 Avengers escorted by 32 Corsairs and 16 Hellcats. That made for an unwieldy beehive, and form up was assisted by squadron leaders dropping their landing gear and flight leaders their tail hooks, but it was a slow process nonetheless. Hay was less than impressed when the strike leader, Lieutenant-Commander W.J. Mainprice, CO of Indomitable’s 854 Squadron, inadvertently contributed to the chaos when he led the formation on two circumnavigations of the fleet before setting out for the target. Unfortunately, three Corsairs and an Avenger had to return to Victorious, a high unserviceability rate attributed to the over-burdened carriers having to range aircraft on deck during the inclement weather. Their return delayed the launch of the second wave, and the 12 Fireflies to augment the strike, and 12 Corsairs each from Victorious and Illustrious designated for RAMROD sweeps against two large airfields, had to pour on the coal to attain their strike positions in time.[xl]

As Air Co-ordinator, Hay submitted a detailed report on his activity during MERIDIAN and that allows us to follow Sheppard quite closely. What Hay saw; he saw. About halfway to the target, the RAMROD Corsairs sped past the main formation to attack the airfields, catching the enemy by surprise at one, but facing intense accurate flak at the other two. As the main strike force got to within 20 miles of the Pladjoe refinery a cluster of barrage balloons, which they had been told did not exist, came into view, floating menacingly over the refineries—they were initially at 2,000 feet but the Japanese raised them as the attack developed. Mainprice, the strike leader who directed the actual bombing, requested the Fireflies to take out the balloons but Hay did not think they received the order, and instead witnessed them carry out their planned rocket attack on the refinery. At 0805, as the Avengers rolled over into their run bomb run from 12,000 feet, Hay noticed black puffs in the sky as Japanese flak opened up—inaccurately at first—and then saw about 25 Tojos attack the escort. Apart from the fray he and Sheppard had a grandstand seat, and Hay was impressed by the tenacity of the Japanese: “Enemy pilots showed as much contempt for Japanese heavy AA as we did and fights were raging all over the target area. It was almost funny to see the aircraft scrapping and all the while AA bursting at all heights up to 15,000 feet. As far as I know no one was lost by this fire and very few damaged.” He was also impressed by the accuracy of the bombing: “The target of No. 1 Wing (Indomitable and Victorious) appeared well hit. No. 2 Wing (Illustrious and Indefatigable) appeared to hit half of theirs.” Victorious’ Avengers managed to put 54 500-lb bombs into the Pladjoe pump house and secondary targets, leaving them a blazing mess.[xli]

An Avenger of Victorious’ 849 Squadron crosses the coast of Sumatra on its way to Palembang during operation MERIDIAN. The RN used a different crew composition than the USN for its Avengers, replacing the radio operator/dorsal gunner with an Observer officer. Seated behind the pilot, the Observer was akin to an ‘operations officer’, fulfilling the navigation duties and contributing to tactical decisions. One Canadian Observer, Lieutenant Ed Jess, RCNVR, commanded 854 Squadron during ICEBERG and in operations over Japan. Whether Observer, pilot or gunner, none would have enjoyed the prospect of having to deal with the jungle, or ‘ulu’, unfolding beneath them. Photo: Sheppard papers

The former Dutch refinery at Soengei Garong operated before the war by Nederlandsche Koloniale Petroleum. The Sumatra refineries produced the bulk of the aviation fuel required by the Japanese, and were thus an important strategic objective. The destruction of the entire complex would be difficult to achieve, and Rear-Admiral Vian’s Force 63 concentrated its efforts on neutralizing pump houses and other critical operating systems. This required good intelligence, effective strike planning and pinpoint bombing accuracy, all of which proved a feature of Operation MERIDIAN. Photo via aukevisser.nl

Ronnie Hay and Don Sheppard’s view of MERIDIAN II. Raging fires and towering smoke give evidence of the “truly impressive” bombing of the Soengei Gerong refinery. Barrage balloons can be discerned to the right of the smoke well above the target, while the Pladjoe refinery still smolders across the Palambang River from the attack on 24 January. Within minutes of this image being taken, the photo sortie was interrupted by Japanese fighters. Photo: Sheppard papers

Hay’s flight lingered over the target until 0823, observing the withdrawal and taking a series of oblique photographs of the results of the bombing. In fact, Hay shot most of the spectacular images that appear in published accounts of MERIDIAN, and when viewing them, one can easily imagine Sheppard’s viewpoint. Hay observed that enemy fighters appeared to be called off at this time, and the Corsairs, Hellcats and Fireflies resumed their positions around the Avengers. As Hay’s flight attempted to join the beehive, they became engaged with four Tojos, “of which I shot down two and the remaining two in my flight damaged one each.”[xlii] Sheppard was more expansive, recounting that Hay’s position as Air Co-ordinator meant that “he and his flight were given free rein to roam the skies at will”:

Because of this freedom, much of the time we were isolated and the Air Co-ordinator was exposed to attack by Japanese fighters prior to the strike, during the strike and after the strike when we circled the targets to take pictures of the damage. On 24 January we were jumped from above and behind by an Oscar who fortunately missed us all with his initial burst and then made an error in judgement by breaking below us after his firing run and then pulling straight up in front of me to regain his original height advantage. When I spotted the error I reversed the turn, followed him up using water injection for additional power and hit with about my second burst. He then fell out of his climb and descended straight down towards the jungle.[xliii]

Sheppard was originally credited with a ‘probable’, but it was apparently later confirmed as his third victory. Hay shot down two others, and of the dogfight Sheppard described above, Hay recalled that two of the Tojos that jumped them “went down in flames into the ‘ulu’.” Sheppard’s logbook entry highlighted the events of the day, but also the grim cost.

Air Cood FLT #3. Strike on oil plant at Palembang Sumatra...3.35 hrs...No. 1 target in Sumatra. Bags of flak, fighters and balloons. Major Hay shot down 2, myself one probable, Charley French two & the CO a single one. Don Chute one, Ray Richards one. Matt Blair, “Dig” Grave, “Bud” Sutton (Saskatoon), “Bax” Baxter, “Tiddles” Brown, Reg Shaw, “Habby” Haberfield shot down.[xliv] Targets well covered with bombs.

Lieutenant Arthur ‘Bud’ Sutton, RCNVR, the Senior Pilot of 1830 Squadron, was shot down during his third strafing run on Talangbetoetoe airfield: according to Illustrious’ CO, “He was last seen at deck level passing through smoke towards the control tower. Here and at the LEMBAK I [another airfield] he was seen to destroy several aircraft in determined attacks.”[xlv] Another Canadian, Chief Petty Officer Herbert Mitchell, an Avenger pilot with Indefatigable’s 820 Squadron, was shot down near the target; neither Mitchell nor his crew survived.[xlvi] All told, Force 63 lost two Avengers, six Corsairs and a Hellcat in combat, while the pilots of a Corsair and a Seafire bailed out over the fleet.

Vian withdrew to the southwest where the fleet refuelled for MERIDIAN II. Knowing they were not yet done with Palembang, tension probably never dissipated amongst the aircrew, and since the Soengei Gerong refinery across the river from Pladjoe had been left untouched, they fully understood the Japanese would be ready and waiting—Vian also thought that POWs taken after the first strike would be forced to disclose their intention. There was little time to rectify faults with the initial mission, although 849’s CO tried his best. “I am still not satisfied with some aspects of the strike”, Lieutenant Foster complained:

The main criticism I have is the cover afforded Avengers between the target and the Rendezvous. I have raised this before and the only improvement that is evident is that the Fireflies are doing an exceptionally good job, but are not being sufficiently assisted by other fighters….Avengers will not always be attacked in this theatre when in squadron or group formations; they will, however, always be attacked when flying singly or in pairs. Therefore, one of the most essential places for fighter protection is along that ten mile stretch from target to R/V. At the moment it appears that the signal for bombing is also the signal for some fighter squadrons to go and find a target of their own.

Vian’s staff sympathized, but concluded the “natural desire of bomber crew to see fighter escort with them all the time was also unreasonable….Very good judgement is required of fighter leaders if they are to act offensively, and yet not leave any bombers uncovered.”[xlvii] Interestingly, Hay, who probably would have sided with Foster, was sidelined during these discussions:

…it may be worth mentioning, that between MERIDIAN one and two, I was placed on the sick list due to eye fatigue. Another VICTORIOUS Fighter Squadron Commander suffered in a familiar manner. I attribute this growing complaint primarily to shortage and, in a few cases, none use of sun glasses. I submit that every endeavour be made to obtain sufficient polaroid sun glasses to equip every aviator and that, whilst in this theatre, their use be encouraged as much as possible.[xlviii]

Much ink has been spilled on the BPF’s logistical shortcomings, but a shortage of sunglasses, an innocuous but important piece of kit, has escaped attention.

The irascible but talented Rear-Admiral Sir Philip Vian. He had earned a justified reputation as a brilliant fighting sailor during the war, but his personality simply rubbed many the wrong way: the USN liaison officer with TF-57 described him as “a neurotic type who can be, and is, extremely rude at times and very difficult to deal with.” Nonetheless, Vian got the most out of what he had, and his forces performed admirably during LENTIL, MERIDIAN, ICEBERG and later operations against Japan. The veteran aviator Lieutenant-Colonel Ronnie Hay thought Vian’s leadership was first-class. Photo via historyofwar.org

On 29 January Force 63 launched MERIDIAN II. Vian and his air staff implemented a few modifications based on the first raid. Instead of striking the two main airfields sequentially, RAMRODs ‘X-Ray’ and ‘Yoke’, of Illustrious’ 1830 and 1833 and Victorious’ 1834 respectively, would hit them simultaneously in the hope of preventing Japanese fighters from getting airborne. Also, rather than attacking the refinery, the Fireflies of Indefatigable’s 1770 Squadron would accompany the Avengers and try to clear a path through the barrage balloons before the bombers rolled in. Finally, wary that the Japanese may launch an attack on Force 63, and miffed by the numerous deck accidents suffered by Indefatigable’s Seafires on 24 January, Vian reinforced the CAP by trimming the strike’s escort by 12 fighters, four from each of the other carriers—not surprisingly, Hay had difficulty persuading Victorious’ Avenger crews that the reduction to their protection was prudent.[xlix]

An Avenger from 849 Squadron makes a perfect approach while landing on Victorious around the time of Operation MERIDIAN. One can easily discern the superior view the pilot had from its cockpit as opposed to that from a Corsair. The sturdy, durable Avenger was extremely popular with aircrew, and was an excellent aircraft on the deck. Note the large bomb bay, which normally accommodated one 1,000-lb. or four 500-lb bombs. Photo: Sheppard papers

Sheppard again found himself with Hay, this time as his Number 2.All told, MERIDIAN II counted 48 Avengers, 48 Corsairs, 16 Hellcats and 10 Fireflies. Apart from a poor form up due to “rather doubtful weather”, the approach to the target was largely uneventful. At 0825 Hay switched his radio to the RAMROD frequency, “and heard Forces X-Ray and Yoke at work. They were on their targets about 15 minutes before we struck and by the sound of things they were far too late. Most of their reports were about bandits airborne.” As the strike force approached the target, the Fireflies accelerated to attack the barrage balloons, apparently destroying three. But they remained a dangerous hazard, and the Avengers of Lieutenant-Commander Mainprice and his wingman spun in after cables sheered off their wings. The Fireflies and Hay’s flight “attracted the attention of the gunners but they were completely unable to cope with gentle evasion”, and this diversion “drew quite a bit of the AA away from the bombers.” The Avengers of No. 1 Wing went in first, and were jumped by eight Oscars just before they began their bomb runs. Hay witnessed the attack from over the target but did not see any friendly fighters move to protect the Avengers. Despite this harassment the Avengers pressed into the attack and Hay judged the results of their bombing to be “truly impressive.” The Japanese fighters then made sporadic attacks on the bombers during their withdrawal, and at least two Avengers and a Firefly were shot down.[l]

Hay’s flight also had a hectic few minutes. After observing the bombing, Hay loitered over the refinery for about three minutes assessing the attack, and then his flight “climbed from 6,000 feet to 10,000 to take vertical line overlap photographs as the flak had died down.” However, Japanese fighters intervened. Accounts of the air battle that followed vary, with differing perspectives shaped by the “swirling confusion” of aerial combat and the jumbled memories of those involved. In his report, penned immediately after the action, Hay simply noted that he was about to start his photo run but “I soon had to change my mind as a Tojo was coming for us. In shooting this one down, we descended to 0 feet and attracted by the gunfire, an Oscar came along, and by 0905 he, too, was dead,”[li] Both kills were shared with Sheppard, who remembered of the second Japanese fighter:

This inquisitive fellow was an Oscar and, obviously attracted by the smoke of the earlier victim, came to have a look. “Hay ordered his flight of three aircraft to climb and not engage. This we did until we had a 1,500 feet height advantage and the leader and I then attacked. It was a vigorous dogfight and, after a series of steep turns, the Jap settled down for a moment straight and level. My shells hit the pilot’s cockpit which glowed with a dull red as the bullets slammed home, then he rolled over and crashed into the trees.”

Sheppard described the combat as “a most exhilarating fight against a very competent and aggressive opponent.” In his logbook he simply said “Major Hay and self knocked down an Oscar & a Tojo between us.”[lii] Sheppard’s return to the fleet was uneventful, but his day was not yet over. In the early afternoon, the CAP shot down a group of eight aircraft that intelligence officers learned were from the “Special Army Attack Corps”, or kamikazes, and more attacks were expected. Sheppard launched on CAP in the late afternoon, and his flight was vectored onto a bogey but it escaped through poor fighter direction. All told, on 29 January Sheppard was airborne for a little over six hours.[liii]

MERIDIAN II was a success. The refinery at Soengei Gerong was off-line until March 1945, and at that time the two Palembang complexes managed only 30 per cent production. But, as historian David Hobbs related, it was a battered group of aircraft that returned to the carriers on 29 January 1945. Six Avengers, two Corsairs and a Firefly were lost to enemy action, and a number of others either ditched or were jettisoned due to battle damage. Of the twelve Avengers launched from Victorious, four were lost and six damaged, and over the course of MERIDIAN I and II, 21 of the carrier’s aircraft were lost or damaged. Captain Denny noted “This is by far the highest casualty rate to aircraft endured during the some dozen operations VICTORIOUS has carried out during the past ten months and it is fortunate that no casualties were suffered in the aircrews of the 13 damaged aircraft.” Apart from aircraft Victorious lost some key personnel, including Lieutenant Leslie ‘Alec’ Durno, RNVR, of 1834, a talented fighter pilot with great potential, who fell victim to flak.[liv] All told, the fleet had lost 32 aircrew thus far in MERIDIAN, therefore news that Vian was cancelling the third strike was, no doubt, well received. “The stage was set for such a final raid” Vian ruefully reported, “fighter opposition largely overcome, enemy special army attack corps shot down, weather possible, position of the Fleet not known – but there was not enough oil.”[lv] With that, the BPF departed the Indian Ocean for Australia to ready for its next series of operations.

Don Sheppard and the air maintainers who looked after his aircraft. Long after the war he remembered “I am full of admiration for those men who always seemed to be cheerful in spite of the conditions under which they lived and worked. I can never praise them enough for ensuring that our aircraft performed perfectly in all respects every time we climbed into the cockpit.” With sadness he added, “I owe my life to those men and I don’t even remember their names today.” Photo: Sheppard papers

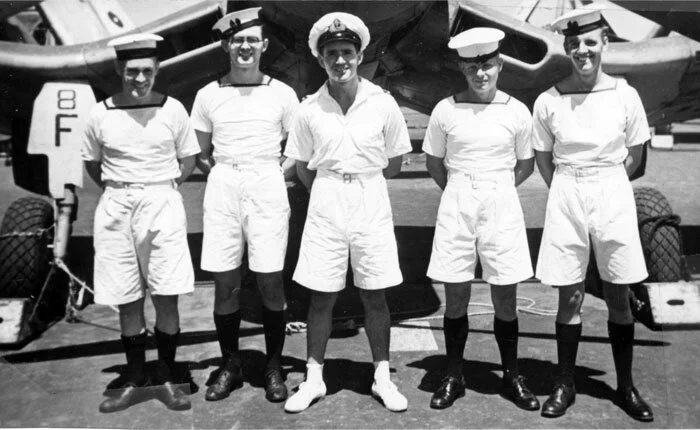

A group of pilots from 1836 Squadron posing in the early autumn of 1944. Don Sheppard is second from the right in the front row. The image becomes poignant from Sheppard’s personal notations—it was his habit to draw small crosses above those who did not survive the war—and betrays the attrition, not just from death, common of a Second World War fighter squadron. Sheppard probably inserted the fates when he completed his tour in the summer of 1945. The front row, from left to right is Sub-Lieutenants C.H. Singleton, P. Coltman, and the Canadians Sheppard and Barry Hayter—those designated as “Relieved” or “Leave” were all actually on Foreign Service Leave. The back row comprises Sub-Lieutenants Matt Blair (shot down during MERIDIAN I), Stan Maynard (shot down during MERIDIAN II), Eric Hill (shot down during MILLET), Lieutenant-Commander Chris Tomkinson (1836’s first CO, killed in ICEBERG), Lieutenant V.A. Fancourt, and Sub-Lieutenants Bill Direen and W.H. Rose. All were Volunteer Reservists. Photo: Sheppard papers

MERIDIAN joined TUNGSTEN and JUDGEMENT, the November 1940 attack on Taranto, as arguably the most successful operations carried out by the Fleet Air Arm in the Second World War—it is remarkable that Sheppard participated in two of them and the other inspired him to become a naval aviator. As always, important lessons were learned from MERIDIAN, the most notable being that the BPF possessed the capability to hit pinpoint targets in strength. Certainly the Americans were impressed, and probably relieved. A myriad tactical lessons also emerged, but one was particularly relevant to the operations the fleet, and Sheppard, would soon embark upon.

As mentioned previously, the FAA had no common doctrine for strafing attacks on targets like airfields. Lieutenant-Commander Gibson, Sheppard’s instructor at the RN Fighter School in Miami, had counselled attacking at low level: “Let your airscrew be just above the ground”, he had admonished his charges, and “never do more than one run on the target.”[lvi] Rear-Admiral Vian had imposed different tactics ahead of Operation LENTIL, observing that “hostile aircraft grounded at dispersal points near airfields will not all be seen by fighters when approach is made over jungle at tree height. In this or similar terrain it is intended that flight leaders shall climb to about 4,000 feet for a bird’s eye inspection of the target before leading down to attack.”[lvii] Though perhaps understandable given the terrain, that procedure negated the element of surprise achieved by a flight of Corsairs suddenly ripping over an airfield at zero feet. Also, there appears to have been no direction as to the number of runs to be made over a target. That was left to the COs of individual squadrons, and as 1834’s leader, Lieutenant-Commander R.W. Hopkins, reported, his unit and Illustrious’ 1830 adopted different tactics during their RAMRODs on Op MERIDIAN. First, Hopkins addressed the importance of surprise:

It is considered that if a low level RAMROD sweep does not achieve complete surprise, it is not only relatively ineffectual but extremely hazardous. The Japanese are renowned for their elaborate aircraft dispersal organization and also for the effectiveness of their light flak. It is unreasonable to expect fighters to poke about an enemy airfield looking for a hidden aircraft, ten, twenty, thirty minutes after an air warning has been sounded.

Like Gibson, Hopkins wanted to get in and out quickly: ‘hit and run’. He cautioned that repeat strafing attacks had proved costly to 1830 during MERIDIAN:

The tactics adopted by this squadron [ie 1834] throughout Operation MERIDIAN were those taught to me whilst doing the Air Fighting Instructor’s Course at Amarda Road. They are the tactics used by the RAF in Burma. Although this squadron does not claim to have destroyed as many aircraft as the Corsair Squadron in HMS ILLUSTRIOUS, our loss due to enemy fire was one Corsair damaged to the extent that the pilot was forced to ditch.[lviii]

Recall that on 24 January flak claimed Lieutenant ‘Bud’ Sutton during his third strafing run over Talangbetoetoe airfield, and another 1830 pilot, Sub-Lieutenant Albert Brown, fell under similar circumstances. Neither ‘hit-and-run’ nor repeated attacks can necessarily be considered the best tactic, and depends on whether the object was suppression of enemy air activity or the destruction of aircraft on the ground. That said, Hopkins’ tactics were definitely more popular in Victorious, and Sheppard certainly favoured that approach. The tactics of low-level interdiction missions have often been controversial—witness the disagreements over the RAF’s RHUBARB, RODEO and RAMROD fighter sweeps over Northwest Europe in 1941–1942.[lix] The debate would continue into the next campaign fought by the BPF, where those who adopted measures different from Hopkins’ ‘hit-and-run’ often paid the price.

End of Episode Two

About The Author

Michael Whitby is Senior Naval Historian at the Directorate of History and Heritage, National Defence Headquarters, Ottawa, where he is currently working on the Official History of the Royal Canadian Navy, 1945–1968. As well as being co-author of the official operational histories on the RCN in the Second World War—No Higher Purpose (2002) and A Blue Water Navy (2007)—he has published widely on 20th Century naval history. Edited volumes include Commanding Canadians: The Second World War Diaries of A.F.C. Layard (2005) and The Admirals: Canada’s Senior Naval Leadership in the 20th Century (2006). He is proud to be the son of two naval aviators, and his work on that subject includes co-editing Certified Serviceable – Swordfish to Sea King: the Technical Story of Canadian Naval Aviation (1995); “Fouled Deck: The Pursuit of an Augmented Aircraft Carrier Capability for the RCN, 1945–64”, Canadian Air Force Journal (Summer and Fall 2010, Vol. 3, Issues 3 and 4), and “Views from Another Side of the Jetty: Commodore A.B.F Fraser-Harris and the RCN, 1946–1964” (2012). He resides with his family in Carleton Place, Ontario.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to extend copious thanks to the Sheppard family; the staff of the Fleet Air Museum, Yeovilton, UK; Pat and Dot Whitby; Mark Styling; Tony Holmes and Osprey Publishing; Randy and Jane Hillier; Pierre Lapprand; Richard Allnut; the HMS Victorious Association and, especially, Dave O'Malley and Richard Lacroix at Vintage Wings of Canada, who all contributed time, material and passion to this project and helped bring it to fruition.

Next Episode: Navy Blue Fighter Pilot–Until the Bitter End

From frozen fjords to steamy Sumatran jungles, Don Sheppard honed his fighter pilot craft in some of the most successful naval aviation operations undertaken by the Royal Navy in the Second World War. In Episode Three of Navy Blue Fighter Pilot, his squadron and HMS Victorious steam for the Pacific to take part in the final destruction of the Japanese Empire. He will need these skills to face the desperation of an enemy cornered in the Ryukyu Islands of Japan. Now, not only the pilots and crews of Victorious’ aircraft are at risk, but the entire crew and the ship herself.

Footnotes

[i] Quoted in Marder, Jacobsen and Horsfield, Old Friends, New Enemies: The Royal Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1942–45 (London 1990), p. 329

[ii] Marder, Jacobsen and Horsfield, Old Friends, New Enemies; Admiralty, The War with Japan, Vol. IV (London 1957) p. 208–213; Clark Reynolds, “Sara in the East”, US Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 87 (December 1961), p. 75–83. Atheling’s Seafires had great difficulty coping with the small deck of a CVE sparking a number of crashes. See Sturdivant, The Squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm, p. 373

[iii] NOAC Ottawa interview with D.M. MacLeod

[iv] Admiralty, The War at Sea, Vol. V, p.512. This was a contemporary narrative produced in the Admiralty and should not be confused with the official history of the same name authored by Stephen Roskill.

[v] IWM interview with Lieutenant John W. Maybank, http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80024839, accessed 12 May 2014

[vi] For Turnbull’s career see Christopher Shores, Those Other Eagles (London 2004), p. 603

[vii] IWM Interview with Commander R.C. Hay, http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80013562, accessed 10 December 2013

[viii] 1834 Squadron Line Book, FAA Museum

[ix] Shores, Those Other Eagles (London 2004), p. 598; and C-in-C Home Fleet, “Honours and awards – Operation LOMBARD and Other Operations off the Norwegian Coast”, 20 July 1944. TNA, ADM 1/29693

[x] “JB Edmundson, RN” at Fleet Air Arm Archive, http://www.fleetairarmarchive.net/, accessed 19 February 2014; D. Brown, The Seafire (Annapolis 1989), p. 93; and ROP HMS Victorious, 21 October 1944. TNA, ADM 116/5302

[xi] NOAC Ottawa interview with D.M. MacLeod. MacLeod was hospitalized with a concussion, and after flying a couple of more missions went home on leave.

[xii] Commanding Officer, 1836 Squadron, “Top Cover Leader 1st Strike”, 24 August 1944. TNA, ADM 1/29992; and Admiralty, The War at Sea, Vol. V, p. 519

[xiii] Major R.C. Hay, “Report of Wing Leader, No. 47 FF Wing”, 27 August 1944. TNA, ADM 1/29992

[xiv] Admiralty, The War with Japan, Vol. IV, p. 218

[xv] Major R.C. Hay to CO Victorious, “Flying Training”, 19 September 1944, FAA Museum

[xvi] Major R.C. Hay, ROP 47th Naval Fighter Wing, 23 December 1944, FAA Museum

[xvii] Admiralty, The War at Sea, Vol. V, p. 667; and Admiralty, The War with Japan, Vol. IV, p. 218–219

[xviii] Sheppard logbook, 17 October 1944; and Major R.C. Hay, “Narratives of Wing Commander and Squadron Commanding Officers”, in CO Victorious ROP, 21 October 1944. TNA, ADM 116/5302

[xix] Sheppard logbook, 19 October 1944; CO Victorious ROP, 21 October 1944. TNA, ADM 116/5302; and Admiralty, The War with Japan, Vol. IV, p. 220

[xx] Osamu Tagaya, “The Imperial Japanese Air forces” in R. Higham and S.J. Harris (eds), Why Air Forces Fail: The Anatomy of Defeat (Lexington 2006) p. 193; and IWM interview with Commander R.C. Hay

[xxi] Fraser had been C-in-C Eastern Fleet since 23 August 1944. With the establishment of the BPF the Eastern Fleet was downgraded to the East Indies Station. Admiralty, The War at Sea, Vol. V, p. 679

[xxii] Winton, The Forgotten Fleet, p. 60. See also Vian, Action This Day: A War Memoir (London 1960)

[xxiii] Sheppard logbook, 28 December 1944. For the rationale for an Air Coordinator see FO Commanding Aircraft Carriers BPF, “Operation Lentil - Report”, 13 January 1945. TNA, ADM 1/30168

[xxiv] Thetford, British Naval Aircraft since 1912, p. 209–214; Sturtivant, The Squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm, p. 333–336; Barrett Tillman, Osprey Combat Aircraft: TBM/TBF Avenger Units of World War 2 (Botley UK 2008); and David R. Foster, Wings Over the Sea (Canterbury 1990). Foster was 849’s CO.

[xxv] Major R.C. Hay, Report on Exercise ‘TILE’, 29 December 1944, FAA Museum