THE MEN WHO FELL TO EARTH

Throughout all of Continental Europe and the Soviet Union during the Second World War, nearly a quarter million aircraft were destroyed in combat, most falling from the skies to crash into the sea, in rural areas, small towns and even cities. With nearly every community in Great Britain being the site of, or near the site of, a crash, you might think this commonplace occurrence between 1939 and 1945 would eventually cause relatively little concern or notice. The truth is that the crashes of every one of these aircraft, the deaths of the men who crewed them and the damage to those on the ground was profound—terribly sad, powerfully traumatic to those that witnessed or were physically and emotionally affected, and formative for young children in the community.

Throughout all of Europe, but especially in Great Britain, Holland, Belgium and France, communities have never quite forgotten the day or the night the men fell from the sky. Hundreds of communities have created memorials to young men they never knew, who long ago died in their midst. Many times it seems, these memorials are dreamed of, sponsored by and lobbied for by men and women who were just children when the event happened or are the children of people who were affected. It is a testament to the depth of feeling engendered by the deaths of aviators, both friend and foe, that a half century or even 70 years on, these plaques and memorials are still being laid, the events unforgotten. This story, so beautifully told by aviation historian Jonathan Falconer, of a Canadian Halifax bomber which crashed in the town of Bradford-on-Avon in 1944 is just one of those multitudes of stories.

One of the two survivors of the crash was Uncle Craig to Vintage Wings of Canada's Chief Pilot, Paul Kissmann, and his wife Laura. The powerful and haunting story of his survival and the sad fate of his mates are told here by Falconer. [Ed]

The Men Who Fell to Earth

‘He died not as some men, by degrees, but swift and sure beneath Somerset’s trees.’

Inscription on the gravestone of Sergeant Norman Simpson, Stretton, Cheshire

Flight Sergeant Brian Hall, RCAF, Pleasantville, New York, USA;

Pilot Officer Don Hernando de Soto Grover, RCAF, Haileybury, Ontario, Canada;

Flight Sergeant Roy Porter, RCAF, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada;

Sergeant Harry Newton, RAFVR, Oldham, Lancashire, England;

Sergeant Norman Simpson, RAFVR, Whitley, Cheshire, England;

Sergeant Graham Evans, RAFVR, Ystrad Mynach, Mid-Glamorgan, Wales

Coincidence played a part in unravelling the story of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) Handley Page Halifax bomber, V for Victor, which crashed at Bradford-on-Avon in 1944. I contacted newspapers in Canada where the crew members came from, but with frustratingly little success. It was only through a chance contact with the Canadian Air Forces Reunion Association that its organizer, Joyce Inkster, happened to know personally one of the two men who had survived the crash, and she passed my details to him. Since my first correspondence in 1985 with survivor Craig Reid, my family and I have enjoyed a warm friendship with the Reids. We visited them in Canada in 1996, and on several occasions since then, we have welcomed three generations of their family as our guests in England.

For more than fifty years Jean Morris, sister of the rear gunner Sergeant Graham Evans, had been searching for the place where her brother had died. Official records had noted the crash site as Christchurch, Wiltshire, but there is no such place: the aircraft came down near Christ Church in Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire. Jean read my letter in a South Wales free newspaper asking for anyone who had known Graham Evans to get in touch with me. She visited me just a few days after reading my letter and I took her to the spot on the hill above the town where her brother had died.

Jean’s visit was a troubling experience for me because I was responsible for stirring unhappy memories that had lain dormant for decades. It is something that I worry about with many of the investigations I have carried out in the research for this book and I have often asked myself ‘should I be doing this?’ There is one part of me that says ‘no, leave the past alone. Let what has happened remain with the past.’ But then there’s another part that says ‘these forgotten events and the men who were caught up in them should not be lost to posterity.’ Young lives were given up well before their time, and for causes that today have little or no meaning for most people.

In 21st century Britain many young people think that Churchill (the wartime premier Winston Churchill) is the name of an insurance company, and that ‘the war’ was the First Gulf War. With this level of understanding of our recent past, what hope is there for perpetuating the memory of a whole generation whose epitaph may well have been ‘Theirs not to make reply, Theirs not to reason why, Theirs but to do and die.’

None of these airmen were born in Bradford-on-Avon, nor had they ever lived in the town. So what is their link to Bradford? Was it by fate or chance, or was it through following orders that they arrived over the town in their burning bomber on a dusky spring evening in 1944?

When Halifax V for Victor crashed into a field in the town near Christ Church it may have been more through luck than judgement that it came down in an open space, away from habitation. However, the actual chain of events on that disastrous spring evening may never be known for sure.

The townspeople of Bradford believed that the Canadian pilot, 22-year-old Flight Sergeant Brian Hall, had valiantly steered his aircraft away from the centre of the town, thereby saving many lives and damage to property. Had the Halifax crashed onto a populated area of Bradford the results could have been disastrous. The aircraft was not carrying bombs because it was on a training flight, but with its petrol tanks filled with high-octane fuel, and with pressurized oxygen bottles and live ammunition on board, the bomber was still capable of wreaking considerable damage if it crashed.

At about 8:30 p.m. on 26 March 1944, in the tiny hamlet of Clivey, near Dilton Marsh, Leonard and Ivy Pickett were pushing their daughter home in her pram from a visit to Leonard’s parents. A shadowy form grabbed their attention as it fell from the sky and swept over their heads, falling into a field beside the remote country road.

Several minutes later at Bradford-on-Avon a Halifax bomber was seen circling the town. One of its four engines was on fire and the aircraft trailed smoke and flame. For some time beforehand the aircraft had been seen flying around Bradford, the pilot presumably looking for a suitable place in which to crash-land.

The Handley Page Halifax was a four-engined heavy bomber of the RAF, RCAF and RAAF during the Second World War, along with similar types like the Short Stirling and the famous Avro Lancaster. More Canadian airmen served with Halifax-equipped squadrons than on those employing the Lancaster. The Halifax could not carry the same payload as the Lancaster, but had a better reputation for survivability. While on squadron strength units of Bomber Command, Halifaxes flew 82,773 sorties and dropped a quarter million tons of bombs. The Bradford-on-Avon Halifax was one of 1,833 “Hali-bags” lost during training and operations. Photo: RAF

Clearly, time had run out for the bomber and its crew when Brian Hall gave the final order to those left on board to save their skins. Three figures tumbled from an escape hatch in the belly of the Halifax, their barely opened parachutes candling in their wake as they fell to earth, too low for the chutes to open.

From where they were standing on Winsley Road, Sholto Morris and his wife Joan heard the unmistakable sound of an aircraft in trouble. Looking up into the moonlit sky, they saw a black shape breaking through the patchy cloud. The sound of surging engines could be heard as the Halifax dropped out of the sky in a spiralling dive. Several small white discs were seen to fall from the aircraft and drift down towards the town. Within seconds, the huge black shape of the bomber was overhead and diving steeply towards the ground. In fear of their lives, the Morrises ran for cover beneath a wall.

Brian Hall was still wrestling with the controls and the rear gunner, Sergeant Graham Evans, was hunched in his rear gun turret when the bomber dived into a field and exploded. V for Victor had crashed in Priory Ground, a rectangular strip of rough pasture on top of the hill above the town, bounded on two sides by Conigre Hill and Winsley Road, with Christ Church at its far end.

The perfectly British village of Bradford-on-Avon today. A view of the town centre with its ancient river bridge over the Avon (in flood last winter). The Halifax crashed on the tree line at the centre top of this photograph. Photo: Jonathan Falconer

Related Stories

Click on image

Six trailer pumps from Bradford and Trowbridge Auxiliary Fire Service arrived at the scene of the crash. Driver Fireman Stan Green of Bradford Fire Station recalls:

‘Leading Fireman Bert Brown was outside the fire station and saw the plane was in trouble. Realising it was going to crash, he called out the fire engine and part-time crew who were on duty. They tore off looking for the crash. As the engine was going up Mason’s Hill they heard the crash. The engine was parked in the Winsley Road close to the pub [the Rising Sun].

‘In the meantime, the two firewomen on duty reported to Fire Service Headquarters that the engine had left the station. Five minutes later they reported the fire. This upset HQ: how can you attend a fire before it’s reported?’

Appliances from stations in neighbouring towns were also called out and quickly came. It took several hours for the firemen to bring the conflagration under control. Rescuers, including the Vicar of Christ Church, townspeople and soldiers from the nearby Army billet at Northleigh, dragged Graham Evans from his gun turret, but he died soon afterwards. Brian Hall was already dead by the time his body was retrieved from the wreckage. The mutilated bodies of the navigator, Don Hernando de Soto Grover, 23, from Haileybury, Ontario; 21-year-old Roy Porter, the bomb aimer, also from Ontario; and wireless operator Harry Newton, aged 22, from Oldham, Lancashire, were recovered and taken to a makeshift mortuary at the ARP post at the town swimming baths in Bridge Street.

Early next morning at Rudge, two herdsmen were on their way milking when they found the lifeless body of the 20-year-old flight engineer, Sergeant Norman Simpson, lying crumpled in a dewy pasture. He had no parachute, which was found several days later hanging in the trees at nearby Norridge Wood. It was plain from the sickening impression in the ground that he had fallen from a great height. The mid-upper gunner, Sergeant Bill Cameron, 22, from Edmonton, Alberta, had bailed out and survived, landing in a field near Westbury.

Corporal Craig Reid was a supernumerary crew member—the eighth man (a Halifax normally carried a crew of seven)—but one who should never have been on the aircraft in the first place. Craig was a ground crew radar technician who had swapped places on V for Victor as a favour to a friend on a ‘hot date’ with a WAAF. Craig took his place to check out the on-board ‘Gee’ radio-navigation aid and H2S radar systems. With Bill Cameron and Norman Simpson, he had bailed out of the stricken Halifax when it got into difficulty over Wiltshire.

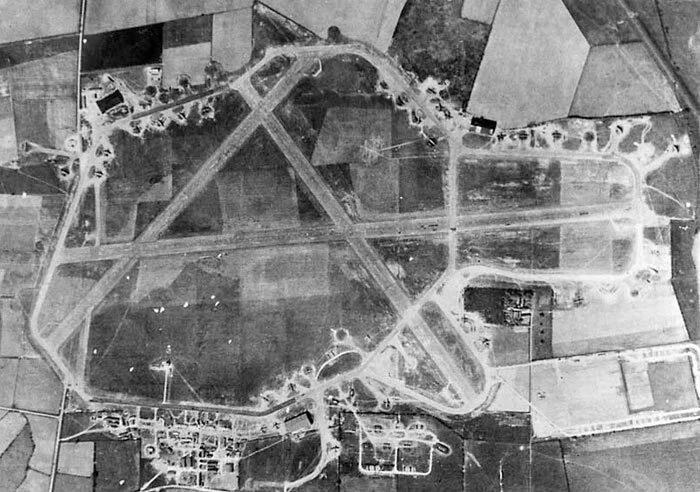

The bomber was a Handley Page Halifax III, serial LW693, call sign V-Victor, which belonged to 425 (Alouette) Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force. It had taken off from its airfield at Tholthorpe in North Yorkshire on a cross-country training exercise. The sortie had taken it on a flight down the length of England to the South Coast, where it had turned north and headed up through Dorset into Wiltshire. It was over southern Wiltshire that the bomber got into difficulties.

RAF Tholthorpe was a Bomber Command base used by two Canadian Halifax squadrons—425 Alouette and 420 Snowy Owl. In December 1943, No. 420 and No. 425 Squadrons were moved to Tholthorpe airfield, having just returned from service with Wellingtons in North Africa. No. 420 Squadron flew 160 operations from Tholthorpe airfield and lost 25 Halifaxes. No. 425 squadron flew 162 operations from Tholthorpe airfield and lost 28 Halifaxes. In all, 119 Halifax bombers were lost from Tholthorpe. Tholthorpe was nearly 400 kilometres from the site of the crash. The squadron had just transitioned to the Halifax from Wellingtons, and this was a training mission. Photo: RAF

The RAF’s official accident report mentions that the pilot lost control of the Halifax between 10,000 and 5,000 feet, conjecturing that it may have been because he let the airspeed get too low. Craig Reid, who had just changed crew positions inside the aircraft to the wireless operator’s seat, beneath and aft of the pilot’s station, recalls the moment trouble began:

‘When the order came “get the hell out of here” I had to crawl through the small hole into the fuselage to the fore of the main spar. Immediately I was pinned to the upper starboard ceiling because of negative “g”. I stumbled and crawled to the rest position to find my chute. They were all in a jumble and my search was desperate. Through the occasional flashes of light I was able to read the ID mark on my chute. Again I was pinned to the port ceiling by negative “g”, a terrifying and seemingly endless episode.

‘Going aft I found the mid-upper gunner upside down hanging by his entangled harness in the mechanism of his gun turret. After getting him out we both proceeded to the rear hatch. There was the flight engineer waiting. Bill Cameron the gunner lined up first, the flight engineer next and then myself. In the roar of the air I yelled, “I haven’t done this before. What do I do?” Bill shouted, “Jump and pull you fool!” ’

‘The two guys went first and I followed. I recall the shadow of the tail plane passing overhead. I don’t recall pulling the cord, but do recall the awfully wonderful crunch of the open chute stopping my plunge. Then the silence—that’s when I became aware that I had been praying.’

A wartime photograph of a young Leading Aircraftman Craig Reid, a radar technician with the RCAF. Reid was one of only two airmen who survived the fire and crash of Halifax LW693. Photo via Craig Reid Family

Len Pickett remembers Craig’s sudden arrival from out of the dusky sky:

‘We’d been round to my father’s place at Standerwick. It was just getting dark and as we got down to the white bridge my wife said “Look at that up there” and we could see the parachute floating. When we got down to the bridge he [Craig] dropped. We called to him and he heard us. He had fallen on his back. We couldn’t get over to him because there was no gate into the field so we got down into the ditch and called for him. He came along and together we got the parachute and harness and put it on the pram. Then we helped him up onto the road and virtually carried him back home.’

‘We took him into the house where he told us he was hungry, so my wife made him some tea and cut him some sandwiches. We didn’t have much rations but we made him welcome. Then I went along and got the next door neighbour to sit with my wife while I cycled up to the phone box to contact the authorities.’

Craig, who had landed at Clivey much to the surprise of the Pickett family, and Bill Cameron, were the lucky ones. Norman Simpson, the flight engineer, had a habit of flying with his parachute harness loosely strapped which was to cost him his life. He pulled the ripcord after bailing out, but instead of floating safely to earth beneath the big silk canopy, he slipped through the web straps and became separated from his parachute, falling to his death over the hamlet of Rudge. Len Pickett also remembers the moment when he came across Simpson’s body in a dew soaked pasture:

‘I went along the lane for about half a mile or so and I looked over into a field next to the road and I could see an airman in a crouched position down on the ground. It was the airman without the parachute.’

The three crew who bailed out over Bradford did so too low for their chutes to deploy properly and were fatally injured. Two of them were caught in the propeller blades as they tumbled from the aircraft: one fell into the trees above Mason’s Lane and the other into the back garden of a house in Coppice Hill. The third fell through the roof of a house on Market Street.

Four auxiliary nurses under the supervision of a local GP, Dr. Beale Gibson, had the unpleasant task of dealing with the bodies of the crew when they were brought to the ARP post at the town swimming baths. They washed the airmen’s bodies and made them presentable before they were driven away up the hill to the mortuary at the hospital.

The following morning people who came to stare at the scene of the crash saw only smouldering debris guarded by troops. On the Tuesday they were allowed into the field to see the roped-off wreckage. For weeks afterwards children found Horlicks tablets and barley sugar sweets from the crew’s flight rations strewn across the field, as well as pieces of twisted metal and splintered Perspex.

Several days after the crash, Canadians Don Hernando de Soto Grover and Roy Porter and American Brian Hall were buried at Haycombe Cemetery in Bath, thousands of miles away from their families and homeland in Canada and the United States. The bodies of the three Britons were returned to their families for burial: Harry Newton to Oldham, Lancashire; Norman Simpson to Stretton, Cheshire; and Graham Evans to Ystrad Mynach in the Welsh valleys.

An RCAF service ID photograph of Pilot Officer Joseph Georges Brian Hall (J/89283), an American from Pleasantville, New York who joined the Royal Canadian Air Force. Hall had been recently married to Barbara Sykes. The image reveals a young pilot, in his early 20s with a serious demeanour. At right is the RCAF grave marker for Hall at the Haycombe Cemetery in Bath, Wiltshire, about twelve kilometres northwest of the spot where he lost his life. Photo: Library and Archive Canada and Jonathan Falconer

Those crew members who were Britons were able to be interred in their hometowns in England and Wales, while the Canadians were buried far away from their families—such are the realities of war. Flight Sergeant Roy Stanley Porter (J/89470), a Canadian Bomb Aimer with 425 Squadron was buried at Haycombe Cemetery in Bath, while the body of 20-year-old Norman Simpson, an RAF Flight Engineer, was returned to Stretton, Cheshire. Photos via Jonathan Falconer

Mid-upper turret gunner, Sergeant Bill Cameron (A/2403), son of Alexander and Louise Cameron of Chilliwack, British Columbia survived the crash of the Bradford-on-Avon Halifax, only to be killed in action with another 425 Squadron crew, four months later over Germany. Don Hernando De Soto Grover (J/85140), who hailed from Haileybury on the shores of Lake Timiskaming in Northern Ontario, was the crew’s navigator. Photos via Jonathan Falconer and Library and Archives Canada

All recently winged aviators like Navigator Sergeant Don Hernando De Soto Grover would go to a professional photographer to get a portrait done for family and sweethearts. This one just underscores the youth of the men involved, their sense of pride and even their innocence. Photo via Grover Family Collection

Bill Cameron returned to flying duties and was promoted to flight sergeant, only to be lost on operations over Germany a few months later on 18–19 July when his Halifax was blown apart by flak over the Ruhr valley. He is buried with his crew at Rheinberg War Cemetery, near Krefeld.

Craig Reid survived the war. He went to university, married and raised a family, and went on to enjoy a career as a social reformer and politician in his hometown of Calgary, Alberta.

On the evidence available in 1944, the RAF’s accident investigators were unable to decide on the cause of the crash. In any case, the RAF had more pressing matters to consider when, four nights later, Bomber Command lost 96 bombers and more than 600 aircrew in a night raid on Nuremberg. It was Bomber Command’s worst loss of the war.

Based on what we know today about the incident, pieced together from witness statements, V for Victor may have crashed because of a technical malfunction that led to a catastrophic engine fire, combined with pilot error. But we may never know for sure.

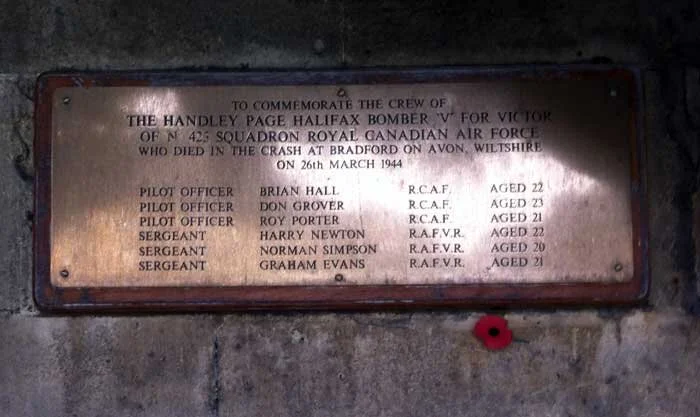

In 1988, I was behind an application by Christ Church Parochial Church Council to the Diocese of Salisbury for permission to place a memorial plaque inside the church to commemorate the crash. The Chancellor of the Diocese, John Ellison, turned down the application and the appeal in 1990 was unsuccessful. Citing legal and ethical arguments to support his decision, he concluded that the reason why nothing had been done in the past was because such a proposal would have been ‘mistaken and inappropriate.’ He went on to say that ‘the erection of a permanent plaque years later involves very different considerations… The sad truth of the matter is that the whole incident was the result of incompetence on the part of Hall, who caused the loss of this aircraft and four of his crew, and who had he lived would probably have been the subject of military disciplinary proceedings.’

Because the result of the RAF’s inquiry into the causes of the crash was inconclusive, it was disingenuous of Ellison to blame the crash on Brian Hall. As a lawyer the Chancellor should have known better than to besmirch the name of a dead man who could not defend himself against such a serious allegation.

Several investigations by the RAF into postwar flying accidents where there were no survivors have laid the blame on the pilot. Where the evidence for such assertions has been flimsy, the families of the pilots concerned have mounted vigorous challenges to the ‘official’ version. (The fatal crash of an RAF Chinook helicopter on the Mull of Kintyre in 1994 comes to mind.)

Conscious of my frustration and disappointment after several years of hoping for a successful conclusion, my father contacted Bradford Town Council to ask if they would be interested in taking over the project. They were.

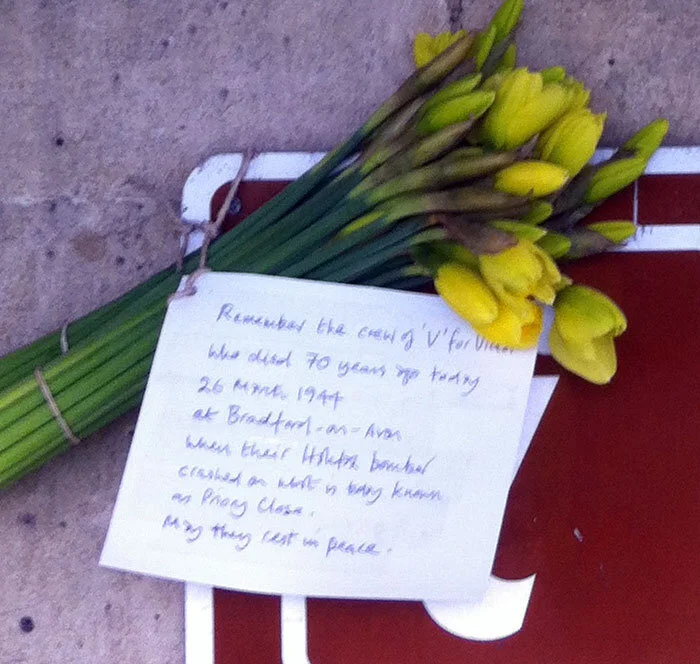

Almost fifty years to the day of the crash, at noon on 25 March 1994, a brass memorial plaque was unveiled outside the Town Council offices in Westbury House Gardens to commemorate the crash and the loss of the bomber’s crew. The sole survivor, 72-year-old Craig Reid, flew in with his wife Verna especially for the ceremony from their home in Calgary, Canada. Jean Morris, the sister of Sergeant Graham Evans, the rear gunner, from Ystrad Mynach, South Wales, was also present to witness the unveiling. With other friends and relatives of the crew, and scores of Bradfordians, they watched a flypast by a Royal Air Force Lockheed C-130 Hercules transport aircraft from RAF Lyneham.

The plaque dedicated to the memory of the fallen airmen was laid in the stones outside the Town Council offices of Bradford-on-Avon. Falconer, who was instrumental in this fitting memorial, took this photo of it on 26 March 2014, 70 years to the day that these brave airmen met their deaths. Photo: Jonathan Falconer’s iPhone

In 1994, 72-year-old Craig Reid returned with his wife Verna to the site of the Halifax’s crash for the 50th anniversary and the unveiling of a plaque in honour of his fallen comrades. Photo via Jonathan Falconer

Also in attendance at the unveiling of the plaque was Jean Morris, the sister of tail gunner Graham Evans.

Craig Reid often asked himself why he alone should have been spared out of the eight men who flew in V for Victor on that spring night. It is a question that troubled him for more than 60 years. Craig found some answers in his Christian faith and he made every new day count through his commitment to family and by working tirelessly for his community. He once told me that every morning when he woke and his feet touched the ground beside his bed he thanked God for another day.

- Jonathan Falconer

On the 70th anniversary of that unfortunate night, a bouquet of yellow tulips was offered to their memory.