ONE WAY TICKET TO DUISBERG

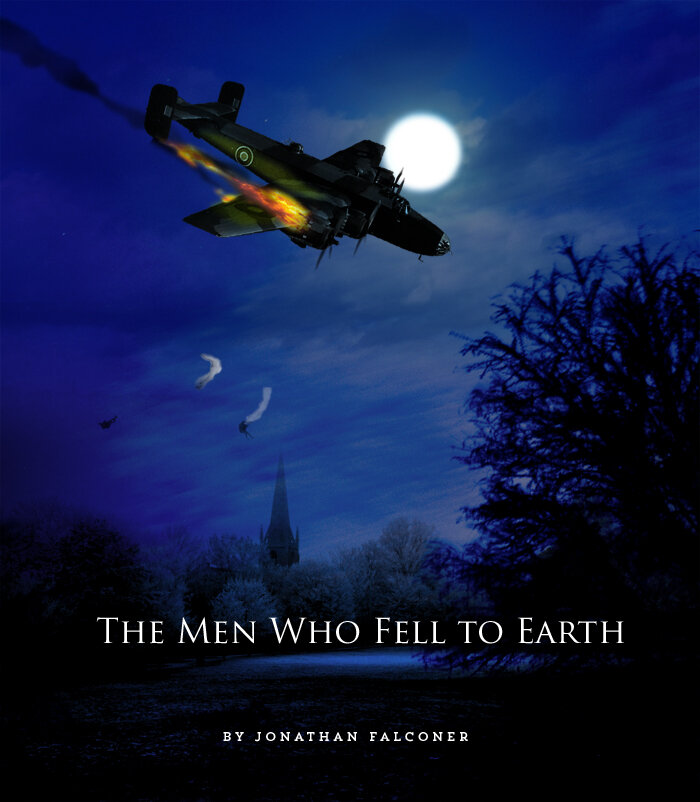

When a Maximum Effort raid was called for by Bomber Command, upwards of 600 four-engined bomber crews could find themselves converging on the turning point for the run-in to target—at night! With 600 bombers timed in groups to cross the target in just twelve minutes, disaster was just a second’s miscalculation away. Vintage News contributor Jonathan Falconer takes us into the cockpit of a Canadian Halifax bomber headed to a tragic destiny—the details of which we will never know.

Flying Officer George “Nobby” Clarke, Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), from Windsor, Ontario, and his 429 “Bison” Squadron Handley Page Halifax crew had already flown 16 ops with 6 Group (RCAF) of Bomber Command when their names were posted on the battle order at RAF Leeming for 30 November 1944: their target, the industrial city of Duisburg in the Ruhr Valley of Western Germany, near the Dutch border.

They were no strangers to the odd lifestyle of Royal Air Force heavy bomber crews: long periods of hanging around the Flight Office, waiting for the battle order to be posted, punctuated by hours of raw fear in freezing temperatures flying a bomber filled with high explosives and petrol through the darkened night skies to bomb a target in Germany. Their very survival hung from a delicate web of skill, operational experience—and luck.

The precise chain of events on this fateful day and night will never be known for sure, but what follows is a detailed reconstruction based on original research by the author.

At some time before noon on the 30th, briefing was announced for 2:00 pm. For those whose churning stomachs could take it, a light lunch in the mess preceded a repeat of the performance earlier that morning before the station had been stood down.

With the formalities of briefing finally over, there was much scraping of benches on the concrete floor as the crews hurried to the locker rooms to change into flying kit. Valuables were handed in and parachutes and escape kits collected. Amidst the usual babble of conversation and the jumble of parachutes, helmets and flying boots, Clarke and his crew struggled into their unwieldy flying gear. Sandwiches and flasks of coffee for the return journey, together with slabs of Fry’s chocolate and barley sugar sweets, were handed out to each crew member from wrappings of newspaper.

.

Flying Officer George “Nobby” Clarke, RCAF from Windsor, Ontario, the skipper of 429 Squadron Halifax Mk III, Serial Number MZ314. The name “Nobby” is a common nickname in England, given to those whose surname is Clark or Clarke. The story behind this is that clerks (pronounced “clarks” in British English) in the City of London used to wear Nobby hats, a type of bowler hat. Photo via Jonathan Falconer

Young George Clarke as a recent recruit with the RCAF—a photograph likely taken in his parents’ backyard. Photo via Veterans Affairs Canada—Virtual War Memorial

Related Stories

Click on image

A typical Bomber Command operational briefing was tense and smoke-filled. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Outside the locker room, buses arrived to take the crews on the bumpy ride to their aircraft, dispersed around the perimeter of the airfield like huge crouching birds. A corporal stood at the open door shouting out the letters by which each aircraft was known. As space became available on a bus for that aircraft’s crew, they climbed on board and were gone into the night. Some crews sat around the dusty floor waiting. Others slouched against the wall, alone with their thoughts. Some paced up and down like caged tigers, unable to relax.

Because they were flying in Halifax Mk III, MZ314, “W”, once again, Nobby and his crew had to wait for transport until most of the other crews had left the locker room. When at last the bus came for them they clambered aboard. The rear door slammed shut after they had seated themselves on the slatted wooden seats, and with a thoughtful silence they rumbled off to dispersal.

Some 576 aircraft from four bomber Groups were detailed for the night’s raid on the German industrial city of Duisburg. These were as follows: 1 Group—16 Lancasters; 4 Group—234 Halifaxes; 6 Group—52 Lancasters and 191 Halifaxes; and 8 Group—25 Mosquitoes and 58 Lancasters.

The target was to be marked by a mixed force of 83 Mosquitoes and Lancasters of the Pathfinder Force, and an airborne “Mandrel” screen (electronic countermeasures) was also to be flown by 88 Short Stirlings, Handley Page Halifaxes and B-24 Liberators of 100 Special Duty (SD) Group and the US Army’s 8th Air Force. Also, a diversionary force of 53 Mosquitoes was to attack Hamburg. (From the total of 576 despatched, 553 aircraft actually attacked the primary target, but 15 crews aborted over enemy territory en route, and eight over friendly territory.)

The bus drew up beneath one of the huge black wings of “Whisky” and the seven boys piled out on to the concrete dispersal pan. A cold wind ruffled their hair and made their eyes smart after the smoky atmosphere of the locker room and crew bus.

The last streaks of sunlight had all but vanished from the western sky. Now, from around the vastness of the airfield, the sound of revving aero engines drifted across to them on the dusky air. The first aircraft were taxiing out to the take-off point. Pilot Officers Bobby Nimmo and Scotty Ogilvie were now ensconced in their turrets, checking on the movements of their guns. Pilot Officer Clarence “Shorty” Short, the Navigator, was tucked away at his snug station in the nose of the aircraft beneath Nobby’s position. At this point in the aircraft the fuselage was some 9 ft. deep. Having checked their guns, Bobby and Scotty climbed back out of the aircraft for a last-minute cigarette and a leak in the grass at the edge of the dispersal.

Nobby looked at his watch. He completed the formalities of signing the Form 700 for the ground crew corporal after a careful check of the control surfaces, wheel tires and undercarriage oleo legs. Then they all climbed into the aft belly hatch of the aircraft: Les Fry (Flight Engineer, and the only Englishman in the crew of Canadians), Nobby, Pilot Officer Frank Manchip (Bomb-aimer) and Pilot Officer Gerrard “Jerry” Paré (Wireless Op) made their way up the fuselage to the nose, Bobby and Scotty to their turrets. Nobby stowed his ’chute and strapped himself into his seat. Outside, on the cold dark dispersal pan, the ground crew were moving the starter trolley into position under the port wing.

Les checked to see that all the fuel cocks below his instrument panel were in their correct positions, then he leant forward to Nobby and declared “Ready for start-up, skip.”

“The last streaks of sunlight had all but vanished from the western sky. Now, from around the vastness of the airfield, the sound of revving aero engines drifted across to them on the dusky air. The first aircraft were taxiing out to the take-off point.” Photoshop illustration by Dave O’Malley

The forward crew positions in a Handley Page Halifax were extremely tight—no place for a claustrophobic airman. One can only imagine how terrible this tight space would have been on a dark night in blacked-out conditions. The single pilot peers down from his seat on the left side of the aircraft, while behind and to his right stands the Flight Engineer. Les Fry would have stood here, monitoring his instruments in a minuscule compartment behind Nobby Clarke’s pilot seat or, when the aircraft was taking off or landing, sat in a fold-up seat (visible at lower left) next to and slightly aft of the pilot, from where he could manage the throttles for the four Bristol Hercules engines. Under the pilot, facing us, sits the Radio Operator in another tiny compartment. Photo: Imperial War Museum, HU 107799

A view looking forward from the Flight Engineer’s position. Directly below the pilot sat the Radio Operator, not visible in this angle. To the right sits the Navigator with his back to the starboard fuselage wall. Beyond him, in the gloom of the forward compartment, peeks the Bomb-aimer. It’s hard to imagine Fry, Clarke, Manchip, Paré and Short all jammed in this tiny, desperately uncomfortable space, in the dark, over enemy territory for 6 hours. At bottom right is the folding seat for the Flight Engineer. Photo: Imperial War Museum, HU 107798

A dashing looking Sergeant Les Fry, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, the author’s cousin, was the flight engineer—and the only Englishman—in Clarke’s otherwise all-Canadian crew. He is pictured here with his brother George. Photo via Jonathan Falconer

Handsome Pilot Officer Robert Floyd “Bobby” Nimmo (left), one of Clarke’s gunners, was just 19 years old. The son of Robert and Rose Helen Nimmo, he hailed from the tiny hamlet of East Coulee, near the Badlands of Alberta. Pilot Officer Scott McCrury Ogilvie (right), another gunner, was just 18 years old. He came from Glace Bay, Nova Scotia on Cape Breton Island, the son of Sinclair and Barbara Ogilvie. It is very interesting to note that all five Canadians in Clarke’s crew were commissioned officers. Given that Nimmo and Ogilvie were gunners (usually crewed by NCOs) and still teenagers, it is rare to see them as officers. It was common practice in the RCAF to award a posthumous commission to NCO aircrew who were killed on operations. There was no official policy that determined this and it was not universally applied, but it was fairly common after 1943. This would explain why Fry was not an officer, as he was the only non-RCAF member of the crew. This is not to say that living gunners could not be commissioned. In fact, many gunners were made officers for exceptional service, gallantry, volunteering to do additional tours or for the destruction of enemy aircraft. Photos via Jonathan Falconer

The Clarke Crew Navigator was 21-year-old Pilot Officer Clarence William Faraday Short (left), known as “Shorty”. Clarence was from Dundas, Ontario, the son of William and Lily Winifred Short. Right: Wireless Operator Pilot Officer Gerrard “Jerry” Paré was, like pilot Clarke, from Windsor, Ontario, the son of Mr. and Mrs. Evariste Paré. Photos via Jonathan Falconer

“Okay, Les, see if they’re ready outside.” Les looked out of the cockpit window and down to the ground beneath. He called back that the ground crew were ready to start the port inner and Nobby switched on the ignition.

“Contact!” yelled the fitter from down beneath the wing. Les pressed one of the four black starter buttons on his panel and the first of four Bristol Hercules radial engines coughed, spluttered and finally roared into life. The same procedure was repeated until all four engines were running. Nobby checked the intercom, opened up the engines to 1,000 rpm and then allowed them to warm up to operating temperature.

Taxiing times for each individual aircraft had been set at briefing and “Whisky’s” time to taxi out for take-off had now arrived. Les was standing behind Nobby, keeping watch on the array of dials on his engineer’s panel. Frank came up the two steps from the nose to assist Nobby at take-off.

With the wheel-chocks pulled away, Nobby gently opened the throttles and the great Halifax trundled and swayed forward, following the aircraft in front around the perimeter track in a stately procession towards the duty runway for the night. Nobby went through his final cockpit check. A green Aldis light from the control van winked through the darkness. “Okay, boys, here we go!” called Nobby over the intercom.

At first the engines were opened up to 1,400 rpm then up to the “gate” as the machine accelerated down the runway. Seven men and 8,000 lb. of bombs headed skywards between the two lines of yellow flare-path lights and away into the darkness.

Although the throttles were almost fully open, Nobby held “Whisky’s” nose down as she strained to leave the ground in order to build up as much speed as possible. Frank eased the throttles through the gate for full take-off power and slammed the clamp on to keep them from slipping back at the crucial moment through vibration. With both hands firmly grasping the control column, Nobby eased it back and the engine note changed as the big black bird clawed its way into the sky at 110 mph, leaving the runway to slip away beneath. The wheel brake lever was nipped to stop the wheels turning before the main gear and tail wheel were retracted with a clunk. The red and green indicator lights went out on Nobby’s instrument panel. W-Whisky was airborne at 4:43 pm.

“With both hands firmly grasping the control column, Nobby eased it back and the engine note changed as the big black bird clawed its way into the sky at 110 mph, leaving the runway to slip away beneath.” Photoshop illustration by Dave O’Malley

Flashback—two months previous, on 24 September

The German defensive positions in the vicinity of the French port of Calais, on the English Channel, were repeatedly attacked in heavy raids by Bomber Command after D-Day—six times in just eight days towards the end of September, when over 3,260 sorties were flown by the RAF for the loss of 12 aircraft—11 Lancasters and one Halifax. The one and only Halifax to be lost was a 6 Group (RCAF) Mk III, (RAF Serial number LW136, letter code Z for Zebra) of 429 Squadron, skippered by the same “Nobby” Clark and much the same crew as on this Duisburg night raid—part of a force of 188 aircraft despatched to attack German troop positions on the afternoon of 24 September 1944.

Briefing was at 2:00 pm and they took off from RAF Leeming in the pouring rain at 4:52 pm. Thirty-one Halifaxes of 6 Group formed part of the force and were timed to make their attack between 6:49 and 6:55 pm. However, when they reached the target, they found it to be completely covered at 2,000 ft. by stratocumulus cloud, so only 126 aircraft were able to bomb. Many of the attacking aircraft came down below the cloud base to bomb visually—instead of on the Pathfinders’ Oboe1-aimed sky markers—where the visibility was better. Clarke took Z-Zebra down to 1,800 ft. to release his bombs at 6:50 pm. The light flak at this height was deadly and very accurate.

The following excerpt is taken from the personal diary of 20-year-old Flight Sergeant Leslie Fry, Clarke’s Flight Engineer, who recorded the alarming events of that day:

‘Paul [the bomb aimer] had just said “Bombs gone”, when a shell hit the kite, by the side of my seat. Several bits of shell hit me; four bits stayed in and had to be taken out in hospital.’...

‘Paul [the bomb aimer] had just said “Bombs gone”, when a shell hit the kite...’ Photo: HistoryofWar.org

The Halifax had sustained very severe damage to both the mid-upper and rear turrets; miraculously the two gunners, Scotty Ogilvie and Bob Nimmo escaped serious injury. The rudder and aileron trim controls, the DR compass, port-outer mainplane and all four engines were badly damaged by flak. With the Halifax crippled and losing height fast, Clarke headed south into France and over Allied lines. He gave the order to abandon the aircraft as it passed over the small village of Clerques.

... ‘I left my position, then Jerry [the wireless op] started to dress my wounds. He had just started when he told me to put on my ’chute as we were going to jump. While Jerry went up to the nose for his ’chute, I dressed myself as best I could.’

‘Jerry, after seeing that I would be OK, went to the rear exit. I went and had a look at my flight engineer’s panel and while I was there I saw that the front escape hatch was open. Shorty [the navigator] was sitting on the floor ready to jump and Paul [the bomb aimer] was pointing down at the deck.’

Short and Paul Roy dropped feet first through the open hatch into the rushing air of the slipstream and down towards the ground. Then Nobby told the remaining crew to wait as the aircraft very soon found itself over rising ground again and the starboard-inner engine was now showing signs of packing up altogether.

‘I then went back to the rear exit: Jerry and Scotty were there, but as the plane was too low for us to jump, I went back to see Nobby. He asked me which engines were U/S. I told him but the engines would not feather. The two outer engines were U/S and the starboard inner went duff. Nobby shouted “We’re going down!” but I did not need telling as I could see for myself. We had only just passed over one hill: I thought we would hit the next.’‘Before we hit I looked out of the astrodome and saw a large hole in the port wing about three feet round. We crashed in a wood. After we came to a stop I got up and had a look at Nobby. The port-inner was still turning over (without any props) so I pulled the cut-outs and she stopped, but was on fire.’

‘I climbed out through the second pilot’s exit, back along the top of the fuselage. The kite had broken her back just in front of the front spar, and by this time the port inner was burning like hell. I went inside the aircraft again and said to Nobby “Let’s get the hell away from here!” and we did.’

‘I dumped my ’chute about 25 feet from the burning plane. As we started running again, a petrol tank went up. We came upon Scotty, Jerry and Bob. Scotty could not walk very well so we started to carry him, but not far as he wanted to walk.’

A little over 10 minutes after releasing his bombs over Calais, Clarke had successfully crash-landed his crippled Halifax amongst the trees at the edge of the Forêt de Tournehem, about 2 miles southwest of Quercamp and some 18 miles inland from Calais.

Still onboard was a 1,000 lb. bomb, which had hung up while they were over the target. Fortunately it did not explode when the aircraft crashed and caught fire, completely burning itself out.

Of all the crew, Les Fry was the most badly injured, with shrapnel wounds from the flak to his left arm and buttocks, which eventually required surgery. Nobby and Bob Nimmo were uninjured, and “Shorty” Short the Navigator found walking painful because he had strained ligaments in his leg as a result of the parachute jump to safety. Jerry Paré, the Wireless Operator/Air Gunner, had suffered several cuts to his scalp and Scotty Ogilvie had bruised his shoulder.

The whereabouts of French-Canadian Flight Sergeant Paul Roy, who jumped at the same time as Shorty, remained a mystery. Not until a few weeks later did his fellow crew members learn that he had been killed bailing out. Paul had been found by Allied troops but was declared dead on arrival at a field dressing station. Although his parachute was seen to open, it is likely that it failed to open sufficiently to slow his descent and he fell to his death. Fry would recover quickly and the Clarke Crew would take on a new Bomb-aimer, Pilot Officer Francis Manchip, who would be with them the night of the Duisburg raid.

Meanwhile, en route to Duisburg, 30 November

The 4 Group station at RAF Burn, just over 40 miles south of Leeming, reverberated to the sound of its resident Halifax squadron, No. 578, getting airborne. It, too, would be one of 4 Group’s squadrons accompanying the Lancaster crews of 1 Group and the Canadians of 6 Group to bomb Duisburg.

At 5:10 pm Halifax Mk III, NR193, “V”, was eased off the runway by her pilot, 28-year-old New Zealander Pilot Officer Vincent Mathias, and was soon lost in the blackness of the night. For Mathias and his British crew, this was their 16th op since joining the squadron from No. 1652 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) at RAF Marston Moor on 18 August.

Flying Officer Vincent Mathias, Royal New Zealand Air Force, and his 578 Squadron crew, pictured at RAF Burn during September 1944. L to R: Flight Sergeant Robert Brown RAF, Wireless Operator; Sergeant Basil Hudspeth RAF, Mid-upper Gunner; Sergeant Roy W.H. Harvey RAF, Navigator; Pilot Officer Vincent Mathias RNZAF, Pilot; Flight Sergeant Geoffrey Lionel Lovegrove, Bomb-aimer; Flight Sergeant Albert Oswald Parry, Flight Engineer; Sergeant David Evans, Rear gunner. The ages ranged from Navigator Harvey at 20 years to Engineer Parry at 36 years. Photo via nzwargraves.org.nz

Meanwhile, Nobby continued in a shallow climb until the airspeed had built sufficiently for him to adjust the fuel mixture and engine revolutions to normal. Les eased the throttles back as the heavy bomber continued to climb. The flaps were now fully retracted and the power eased off again to suit the rate of climb selected. Shorty gave Nobby a course to steer and with the reassuring glow of the red and green navigation lights of the other aircraft in the sky all around them, they flew south in the climb towards their first checkpoint over Reading.

To prevent the Germans receiving early warning of their impending arrival the crews of 1, 4 and 6 Groups, which comprised the main attacking force, had been briefed to stay below a height of 6,000 ft. until they reached the town of Vervins in Northern France at 0400 degrees E over Picardy. In fact, the Luftwaffe controllers concluded that the Main Force’s southeasterly course threatened the Frankfurt area so one Gruppe of night fighters was sent to a beacon in that area to await the arrival of the bombers.

The three groups made rendezvous over Reading where, one by one, their navigation lights were turned out as the armada of bombers droned its way southeastwards at a speed of 200 mph towards Beachy Head, where it left the shores of England behind. Navigating with the aid of “Gee”2, landfall in France was made over the Somme estuary in the inky blackness at 6:35 pm. The force headed inland for 110 miles across the bygone killing fields of the Western Front until it reached Vervins and the latitude of 0400 degrees E.

Lit only by the dials of their various instruments, the crew huddled in the darkness, as the Halifax droned toward its destiny. Photoshop Illustration: Dave O’Malley

“Navigating with the aid of ‘Gee’, landfall in France was made over the Somme estuary in the inky blackness at 6:35 pm.” Photoshop illustration by Dave O’Malley

At this point the bomber stream split into two diverging courses and climbed up through the thick covering of stratocumulus, heading northeastwards across Belgium in a long slow climb over a distance of 130 miles to the bombing height of 18,500–19,500 ft. The aircraft broke through the cloud into the hazy light of a full moon, with broken patches of cirrus scudding high above them. Passing through the 10,000 ft. height band the order came from each aircraft’s skipper for his crew members to switch on their personal oxygen supplies. In W-Whisky, Les was busy keeping a log of the engine conditions and recording the state of the fuel load.

Confused by the strong “Mandrel”3 screen, the Germans were kept guessing as to where the bombers would finally strike. By the time the two formations had crossed from Belgium into the Dutch province of Limburg, a major course change was imminent. At a point between Eindhoven and Weert the two separate formations turned eastwards onto parallel, but still separate, courses for the 50-mile run-in to the target. 4 Group’s Halifaxes were now slightly ahead of those from 6 Group.

The tactical plan was for the two Main Force formations and a special “Window”4 force comprising two Mosquitoes from 608 Squadron, Downham Market, to converge on the Ruhr from different directions. The Pathfinder Force was timed to drop its markers between 7:58 and 8:06 pm from a height of 16,800–18,500 ft. With the Main Force attack, 1 Group’s Lancasters were timed to bomb between 8:00 and 8:04 pm; 4 Group was to concentrate its aircraft over the target area in 3-minute waves between 8:00 and 8:06 pm; 6 Group similarly between 8:06 and 8:12 pm. The whole raid was timed to last just 14 minutes with 553 bombers being streamed over the target during this time.

At about 8:00 pm over the Dutch town of Weert, Nobby had almost certainly just turned on to the final leg that ran into the target when something went very badly wrong. Frank, the Bomb-aimer, had gone down into the nose to check his bomb sight and fusing panel; Les had gone aft beyond the cockpit bulkhead to check the master fuel cocks. Nobby called up the gunners for them to keep their eyes peeled for enemy fighters. Shorty’s voice came over the intercom giving Nobby the ETA on target. Each member of the crew was busy at his station as the procession of aircraft in each formation began to converge for the final run-in to the target.

“At about 8:00 pm over the Dutch town of Weert, Nobby had almost certainly just turned on to the final leg that ran into the target when something went very badly wrong.” Photoshop illustration by Dave O’Malley

In the blacked-out towns and villages that dotted the flat Limburg countryside far below, the war-weary inhabitants were settling down for the evening. Two miles from the Belgian border, in the tiny village of Altweerterheide, the Blok family, tired after a hard day’s work on their farm, were settling down for a well-earned rest in their farmhouse kitchen having just put their youngest children to bed.

High over Weert disaster struck. Two fully-loaded bombers collided. Nobby and his crew were in one of them, Vincent Mathias and his crew in the other. Violent explosions and gunfire in the night were sounds that the Bloks were all too familiar with, living as they did in a corner of Europe that for five years had witnessed the nightly procession of Allied bombers droning their way east towards the Ruhr. The gut-wrenching sound of rending metal high in the sky that night was nothing out of the ordinary for them. Not, that is, until shards of razor sharp metal, heavy engines, iron bombs and the pitiful remains of what moments before had been two four-engine bombers and 14 men, rained down about their farm in the meadow.

The two fatally damaged aircraft had become locked together by the force of the impact and had fallen 18,000 ft. to hit the ground two miles south of Weert, near Altweerterheide. Wreckage from the two aircraft and the bodies of the 14 crew crashed to earth in a meadow bounded by three farms, close to a road leading towards the small town of Bocholt over the Belgian border nearby. It was a miracle indeed that the inhabitants of the village escaped injury since pieces of the falling aircraft narrowly missed smashing through the roof of the Blok’s farmhouse where the youngest members of the family lay sleeping. For some reason the wreckage did not catch fire despite the presence of a volatile cocktail of high octane fuel, bombs, ammunition and pressurized oxygen cylinders. There were no survivors among the two crews.

“The gut-wrenching sound of rending metal high in the sky that night was nothing out of the ordinary for them. Not, that is, until shards of razor sharp metal, heavy engines, iron bombs and the pitiful remains of what moments before had been two four-engine bombers and 14 men, rained down about their farm in the meadow.” Photoshop illustration by Dave O’Malley

The collision must have been severe enough to prevent all 14 men from bailing out. With the terrific pressures exerted on their bodies by “G” forces as both aircraft tumbled out of control, even if they had been struggling to reach the emergency hatches, the effects of high positive “G” would have pinned them to the insides of the fuselages, rendering them completely helpless.

Meanwhile, up above, the rest of the bomber force droned its way inexorably eastwards towards Duisburg, some 40 miles distant, oblivious of the fate that had befallen the two crews. Most of 429 Squadron’s aircraft had returned safely home by 11:00 pm, the last aircraft touching down on Leeming’s runway at 11:18 pm. The attack on Duisburg had not been concentrated but, nevertheless, much fresh damage had been caused to the city. Fires were visible from up to 60 miles away by homeward-bound crews. Some 528 houses were destroyed and 805 seriously damaged. Contemporary reports do not mention any damage to industrial premises, but 246 people were killed, including 55 foreign workers and, sadly, 12 prisoners of war.

The starboard wing section from one of the Halifaxes lies in the field where it fell. The wing centre section has been torn away from the centre fuselage, and the engine bearers have been removed, exposing the front spar. There are holes in the alloy stressed skin surface of the upper mainplane. Photo via Blok family archive

The tangled remains of Halifaxes MZ314 and NR193 at Altweerterheide photographed in July 1945 by the Blok family on whose farmland they crashed. In the foreground is a propeller from a Bristol Hercules engine and what appears to be part of an exhaust collector ring to the right of the propeller hub. To the left of the prop are oxygen bottles, control cables, what appears to be part of a throttle quadrant, part of the front wing spar, and another engine and propeller. Photo via Blok family archive

Salvaged aluminium wing sections from the crashed bombers are driven away on a lorry to be melted down for scrap. Photo via Blok family archive

Altweerterheide was already in Allied hands at the time of the crash and had been so since the beginning of November. On the day after the crash, Friday 1 December 1944, British military authorities arrived at the scene to examine the wreckage and to collect the bodies of the 14 crew before their eventual burial in the nearby Cemetery Keent at Nederweert. One year later, the bodies of all 14 men were exhumed and reburied in the newly opened Canadian War Cemetery at Groesbeek near Nijmegen.

We shall never know for certain the precise chain of events which led these two bombers to collide over Holland with such tragic consequences. The spectre of mid-air collision was forever in the back of the minds of the bomber crews and the raid planners at Bomber Command HQ, particularly during the huge massed raids that marked the culmination of the strategic air offensive from mid-1944 until the war’s end. But, with many other factors more likely to pluck them from the skies, such as flak, fighters, the elements and fatigue, mid-air collision was just another part of the calculated risk of operational flying, particularly at night. Bomber Command lost approximately 112 aircraft through collision between July 1942 and May 1945, 2,278 to German fighters, 1,345 to flak, and 2,072 to unknown causes (probably one, or a combination of each, of the former).

By Jonathan Falconer

Afterwords

Pilot Officer Francis Manchip, Bomb-aimer, Duisburg Raid

We were unable to acquire a photograph of 24-year-old Bomb-aimer Pilot Officer Francis Manchip, but he hailed from Toronto. Manchip was the son of William and Hilda Manchip, of Toronto, Ontario. He left behind a widow, Ada Kathleen Manchip. On the first anniversary of Manchip’s death his wife purchased a small “In Memoriam” notice in the Toronto Daily Star, which read:

In loving memory of my husband, Pilot Officer Frank Walter Manchip, killed on active service overseas, Nov. 30, 1944 along with the members of his gallant crew. Buried at Bosh Overbeek. No pen can write, no tongue can tell, my sad and bitter loss, But God alone has helped to bear my heavy cross. Greater love hath no man than this, to lay down his life for his friends. Remembered by his loving wife, Ada.

Ada Manchip never remarried. She died in Mississauga, Ontario in 2005.

Pilot Officer Joseph Alphonse Paul-Émile Roy, Bomb-aimer, Calais Raid

In addition, we were unable to find a photo of the original Bomb-aimer in Clarke’s crew, Paul Roy, killed two months prior to the Duisburg Raid. The Canadian Virtual War Memorial provides his stone however in the Calais Canadian War Cemetery; Pas-de-Calais, France. Roy was the son of J. Émile and Rose Roy, of Montmagny Station, Québec.

Pilot Officer Paul Roy’s headstone at Pas-de-Calais

1. Oboe was a British aerial blind bombing targeting system in World War II, based on radio transponder technology. Prior to a mission, a circle was drawn around one of the Oboe transmitters so that it passed over the selected target. The bombers, one at a time, would then attempt to fly along this path towards the target. The Oboe operator in England would use the equipment to see if the bomber strayed from the path, and give the pilot instructions on how to regain it.

2. Gee was the code name given to a radio navigation system used by the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. It measured the time delay between two radio signals to produce a “fix”, with accuracy on the order of a few hundred metres and range around 350 miles (560 km). It was the first hyperbolic navigation system to be used operationally, entering service with RAF Bomber Command in 1942.

3. Mandrel, a broadband radar jamming system, blinded German radar systems like Freya, Wassermann, and Mammut early-warning radars by throwing out radio noise on the Freya band. Mandrel was originally installed on fighters that escorted bomber formations to their targets. When Mandrel was installed on RAF bombers beginning in December 1942, RAF bomber losses fell substantially.

4. Window, as it was known by the British, is now called chaff and is a radar countermeasure in which aircraft or other targets spread a cloud of small, thin pieces of aluminium, metallized glass fibre or plastic, which either appears as a cluster of primary targets on radar screens or swamps the screen with multiple returns.

![‘Paul [the bomb aimer] had just said “Bombs gone”, when a shell hit the kite...’ Photo: HistoryofWar.org](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1628532951295-M0JFOGTD8BWWO0M1KGPV/Duisberg24.jpeg)