NAVY BLUE FIGHTER PILOT – Episode One

At Vintage News, it is our pleasure to bring you stories of aviation in all its glory—the cultural, historic, tragic, humorous, luminous and industrial tales of a flying world that has locked us all in its grip since we were young. Aviation history is stranger than fiction—countless dramas played out upon a worldwide stage with inspiring and legendary characters.

I am happy to be a person who relates our aviation history to such a worldwide audience, numbering now over 12,000, but I am no historian. I know that. I, and many of our contributors in the past, are storytellers for whom the work and discipline of a true historian must give way to the emotion and drama of events. We tell them in the best way we can, for these have been stories that have stirred deep emotions and inspired us to capture lost or about-to-be-lost stories.

Michael Whitby, the Senior Naval Historian at the Directorate of History and Heritage, National Defence Headquarters in Ottawa, comes by his passion for naval and naval aviation history honestly—he grew up the son of a Canadian naval aviator and lived on Canada’s most important naval air station, HMCS Shearwater in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. Some of the great Canadian naval aviation heroes, including Don Sheppard, were neighbours on a base where the streets had names like Corsair Drive, Fulmar Avenue, Martlet Place, Firefly Terrace and Barracuda Drive. The historic aircraft of the Navy flew over his head. The grey warships came and went past McNabb’s Island outside his window. He was raised a Navy boy, fed on stories of legendary men, ships and aircraft. His future career was probably preordained.

This story of Lieutenant Don Sheppard, one of Canada’s beloved aces from the Second World War, serves to launch our website farther into the historical orbit. With unprecedented access to Sheppard’s personal logbook, documents and photo albums, this three-part series relates the enlistment, training and Second World War operational flying career of a legendary fighter pilot as he fights with the Home Fleet, British Eastern Fleet and British Pacific Fleet in actions from snow-covered Norway to sun-blasted Sumatra.

There have been other true historians as well who have written stories for our website in the past, and their excellence elevates our reputation to a higher level. Today, we take it higher still. So climb aboard, strap in, and cinch down as we offer up Navy Blue Fighter Pilot, by Michael Whitby. – Dave O’Malley, Editor

Episode One: First a Sailor, Then an Aviator

Canadians like their fighter pilots. Perhaps more than any other figures in our military heritage they are a source of pride and admiration that even transcends generations. Bishop, Barker, Beurling, Collishaw and Gray are amongst those who receive the most acclaim—in the typical understated Canadian way—but there are many others whose names, if not celebrated, still ring familiar and are held with respect. Donald John Sheppard is one of those lesser lights: “A gallant young fighter pilot with plenty of dash and enthusiasm”, according to his superior officer.[i] Because he flew for the Royal Navy from a British aircraft carrier and met his greatest success on the other side of the world in theatres of war not as well known to Canadians, his name does not resonate as much as some others. In fact, Sheppard is probably better known in the United Kingdom than he is in Canada--the British company Hobbymaster has produced a die-cast model of the Corsair he flew in the Pacific and his exploits have graced the covers of books and journals published in the UK.[ii] But, as this study of his Second World War service demonstrates, his career is worthy of attention. The quiet young man from Toronto—he was just 21 when the war ended—faced a range of experiences in operations that took him from north of the Arctic Circle to south of the Equator, and which put him at the forefront of some of the most significant missions carried out by the Royal Navy in the Second World War. During this time Sheppard fulfilled his duties as a fighter pilot with exemplary ability; an indication of his skill is that he met enemy aircraft six times in aerial combat and on each occasion emerged the victor. The goal is not to heighten acclaim for Sheppard—his modesty would protest any such motive—rather to portray the experiences of a young Canadian at war, one who through skill, opportunity and fortune, realized tremendous success that earned him the respect of his colleagues and superiors.

One of the happy side-effects of biographical history is that the study of an individual opens avenues into related subjects. Don Sheppard was a naturally skilled fighter pilot, but that alone does not account for his success. He took his training and preparation extremely seriously—for example, he preserved several critical training documents for continued study—and an examination of his professional development demonstrates its critical influence on his success and, perhaps, even his survival. Likewise, by tracing his flying experiences on almost a mission-by-mission basis, a process made possible through rarely used primary source material such as training and combat reports as well as the author’s interviews with Sheppard, one can weave his experience into the overall context of the campaigns in which he flew, creating greater understanding of those events. Finally, through Sheppard we gain insights into the operational history of the Chance-Vought Corsair, his favourite aircraft; life in the 47th Naval Fighter Wing and 1836 Naval Air Squadron, the units to which he belonged; and flying from the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious, the ship in which he was proud to serve. We are also introduced to his fellow naval aviators, including one of the outstanding fighter leaders of the Second World War, Lieutenant-Colonel Ronnie Hay, as well as a number of Canadians who also deserve to be remembered. We are not just shining a light on Don Sheppard, but on the experiences of a group of young men wearing dark-blue who flew at sea in the latter years of the Second World War. As with the other ‘fighter boys’ who went to war, theirs is a tale worthy of illumination.

The Illustrious-class carrier HMS Victorious was Don Sheppard’s home from the time he went to sea in March 1944. Like her sister ships Illustrious, Formidable and Indomitable, Victorious was a workhorse of the Royal Navy, seeing action in critical operations in theatres around the globe. Designed to carry 36 aircraft, by the time Sheppard joined ‘Vic’ she was operating more than 50 which, with the additional crew required to fly and maintain them, imposed great stress on her organization and systems. The outstanding feature of the class turned out to be the armoured flight deck, which allowed them to shake off damage that would have forced other carriers out of action. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Victorious pounds through heavy seas while working with the Home Fleet in northern waters during 1942. Her deck park features Fairey Albacore TBRs and a Fulmar fighter, both typical of the obsolescent aircraft the FAA had to rely upon at that stage of the war. The screen across the fore end of the flight deck was meant to block the wind, which could cause damage to the fragile biplanes and made it difficult for sailors to wrestle them around deck. The high seas and wind evident in this image demonstrate well the significant challenges naval aviators routinely faced when operating aircraft from the pitching deck of a carrier. Photo: courtesy Sheppard papers

Related Stories

Click on image

Part One

Don Sheppard’s entry into the service was probably fairly typical of anyone from a Canadian household with boys of enlistment age. During summers at the family cottage on Lake Simcoe, Ross Sheppard instilled a love of sailing in his three boys so it is not surprising that all three went into the navy. The eldest brother Bill was the first to go, accepted into the RCNVR and heading overseas in the summer of 1940. Don, the youngest of the three boys, bucked the natural order. Still attending Toronto’s Lawrence Park Collegiate, as he later recalled, he had joined the militia “with no particular aim in mind but to get some experience in the military before the war was over—since this was 1940 or 41, you can see that I was pretty young and naïve.” His next action discloses early signs of the cunning and initiative—and humour—generally associated with successful fighter pilots:

One day in 1941 I found an application form for the Fleet Air Arm on my brother’s desk in the room which we shared at home. On reading the form I discovered that the Royal Navy was actively recruiting Canadians for the Fleet Air Arm. It was apparent to me that I was far better qualified than my brother to enter this service which had fired my imagination with its success at Taranto and in the destruction of the Bismarck. I therefore filled in the application (unbeknownst to my brother) and sent it off to an address in Halifax along with the necessary supporting papers. Much to my surprise (and my brother’s) I received a reply in about a week’s time instructing me to get an aircrew medical from the RCAF and pay my own way to Halifax as soon as I was 18, which I did.[iii]

Arriving on the east coast in January 1942, Sheppard reported to HMS Saker, a ‘stone frigate’ consisting of a small cluster of buildings on the airfield at Eastern Passage, now CFB Shearwater. There, after passing a preliminary interview, he swore allegiance to the King, received the lofty rank of Naval Airman 2nd class (NA II), and was issued with a Pay and Identity book, uniform, hammock and kit bag. Days later he embarked in the armed merchant cruiser HMS Alcantara, which proceeded to the UK in convoy HX-174. A reminder that he was off to the war came on the night of 17 February 1942 when a U-boat torpedoed a ship in the convoy.

The armed merchant ship HMS Alcantara. Prior to joining the navy Don Sheppard had never been outside Ontario, but after taking the long journey by train to Halifax, he found himself crossing the North Atlantic in a convoy that came under attack by U-boats. Photo: Imperial War Museum, © IWM (FL 386)

Sheppard reported to HMS Daedalus, the Fleet Air Arm’s (FAA) main establishment at Lee-on-Solent, where he immediately received another opportunity for sober reflection. On 12 February 1942, the day before Sheppard arrived in the United Kingdom, Fairey Swordfish of 825 Squadron had been decimated in a futile attack on the battle cruisers Gneisenau and Scharnhorst during the infamous ‘Channel Dash’. 825 was based at Lee-on-Solent, and Sheppard’s first duty upon arrival at Daedalus was to attend the memorial service. “When advised at the service that the entire squadron had been shot down”, he recalled, “I had some misgivings about the military service I had chosen to pursue and made a silent wish that I would ultimately be selected to be trained as a fighter pilot rather than a torpedo/bomber/reconnaissance (TBR) pilot.”[iv] That decision was some time away, and after passing a final selection board, Sheppard spent the next few months receiving basic naval training at HMS St Vincent in Gosport. The RN took great pains to emphasise that the FAA was just one branch of the navy: in the words of aviation historian Stuart Soward, “One aim of St Vincent was to instil in all Royal Navy aircrew the over-riding doctrine that an airman is first and last a seaman.” According to Ted Davis, another Canadian on Sheppard’s 38th Pilots Course, “This was where we were indoctrinated into the navy, where we were inspired to become naval airmen. The living conditions were spartan, the discipline was rigid, and the food was anything but appetizing. And yet I know the majority of those who trained there will recall those days with a certain amount of nostalgia.”[v]Aviation trainees passing out of St Vincent entered one of two schemes: initial pilot training by the RAF in the UK followed by advanced training with the RCAF in Canada, or completing all stages with the United States Navy. Sheppard took the latter route, probably on the basis of personal choice. This program was known as the Towers Scheme, after Captain John Towers USN, who proposed in the summer of 1940 that the USN train FAA carrier pilots for service in American Lend-Lease aircraft. The scheme ultimately produced more than a third of the RN’s pilots and enabled many of their squadrons to work-up in superior circumstances in the USA.[vi]Sheppard’s initial flying training proceeded routinely. He began at the Flight Preparatory School at Naval Air Station (NAS) Grosse Ile outside Detroit, Michigan. Known as an ‘E-’ or Elimination-Base, the sprawling base at Grosse Ile was home to about 3,000 personnel including 750 student pilots. It was basic flying school, so one mistake and you washed-out. On 15 September 1942, Sheppard went up for the first time in a Spartan NP-1 primary trainer, with Lieutenant (jg) Syd Roth USNR as his instructor. The two flew together a lot over the next few months, and years later Sheppard remembered Roth’s kindness and patience, and how he instilled him with confidence. On 25 September, after 12.8 hours dual, Sheppard successfully soloed in a NP-1 numbered 3689. He continued to refine his skills, mostly under Roth’s tutelage, and at the end of September moved up to the more powerful Stearman Kaydet with increased concentration on precision flying. On 7 December 1942, after accumulating 48.3 hours at the controls, Sheppard graduated Primary Flight Training—in the certificate stamped in his logbook, Roth wrote “No noticeable points to watch.” With that hurdle behind him, Sheppard headed south to the USN’s main aviation training center at Pensacola, Florida for Intermediate Flight Training. It was probably at this point that he was selected for fighters, and at Pensacola he flew the heavier and more powerful Vultee SNV-1 Valiant as well as variants of the North American SNJ Texan. Training serials prepared him for many aspects of carrier flying, including formation flying, night operations, aerobatics, gunnery training and dummy deck landings. When he left Pensacola in mid-May he had 141.8 daytime hours as pilot, 5.8 at night. His status also improved: he was now a gentleman flyer with the exalted rank of Temporary Midshipman (A), Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR).[vii] He was probably more proud of the fact that he had earned the right to wear the wings of both the Royal and United States navies.

Naval Air Station Grosse Ile was located on the southern tip of Grosse Ile, Michigan, just south of Detroit. During the Second World War, NASGI was one of the largest primary flight training stations and it was there that more than 5,000 pilots, mostly naval cadets, received their introduction to flying. On 15 September 1942, Sheppard soloed at Grosse Ile in a Spartan NP-1 primary trainer. Image via Wikipedia

The next stages of Sheppard’s training through the second half of 1943 were the most influential in his development as a naval aviator and saw him begin to fine-tune the specialized skills of a fighter pilot. From 20 May to 2 July 1943 he undertook the Royal Navy Fighter Course at NAS Miami, located at Opa Locka airfield, a little more than ten miles north of downtown Miami. This was an important milestone. Not only would Sheppard learn the finer points of fighter combat, but for the first time since leaving the United Kingdom, he would be imbued with Royal Navy, rather than USN, doctrine, tactics and procedures. In short, although there was still some involvement with USN instructors, he would learn to fight from a FAA perspective. For this, Sheppard was in good hands. The Fighter Course was headed by Lieutenant-Commander Donald Gibson, DSC, RN, who had a remarkable wartime career. He had flown Gloster Gladiators and Blackburn Skuas in the trying 1940 Norwegian campaign where, amongst other harrowing experiences, he survived a doomed raid on German warships in Trondheim harbour. On what became known as ‘Black Thursday’ throughout the FAA, eight of fifteen Skuas were shot down. Gibson, who retired as a Vice-Admiral, compared it to the Charge of the Light Brigade, pointedly observing that “ideally all future admirals should ideally be shot at in an aeroplane while they are still young.”[viii] In the Mediterranean, Gibson shot down three enemy aircraft in operations at Oran and Dakar, and flying a Fairey Fulmar during the Battle of Matapan, destroyed a JU-88 and boldly strafed the Italian battleship Vittorio Veneto. On a mission soon after, his Fulmar was shot-up by enemy aircraft causing Gibson to crash while landing on HMS Formidable; after skidding over her bow into the sea, he could clearly hear the carrier’s screws as she thundered overhead. He got out but his Observer did not. Later, Gibson commanded 802 Squadron flying Grumman Martlets off HMS Audacity, where he had another narrow escape when the carrier was torpedoed and sunk during the battle over convoy HG-76.[ix] By any measure, Gibson had seen a lot, and he took great pains to pass his considerable know-how along to the budding naval aviators under his tutelage.As one example, Gibson distributed a 32-page primer on fighter operations titled “Straight from the Horse’s Mouth”, which he authored with other instructors at the fighter school. Based on “experience, sometimes bitter”, its purpose was to give the young flyers a reference book to recall the important elements of their training after they went into action. Gibson explained “the art of being a fighter pilot consists of thirty percent knowledge and seventy percent horse sense, neither being any use without the other”, and he expanded upon that credo in chapters covering subjects such as General Advice to the Fighter Pilot, Strafing, Formation and Escort, Harmonizing of Guns, and Deflection Shooting. Some aspects of that advice would prove particularly influential to Sheppard. As just one example, Sheppard recalled “At that time, the USN doctrine called for fighters to come in high with the bombers and accompany them down in their attack in steep dives in order to provide FLAK suppression. However, when we arrived in Miami the RN Liaison Officer [Gibson] advised us to disregard the USN strafing techniques and concentrate our efforts on a very low level high speed approach to the target which was only to be attacked once.”[x] “Keep low”, Gibson advised in his chapter on strafing in “Straight From the Horse’s Mouth”, and “when I say Low I do not mean keep at about fifty feet, I mean five. Let your airscrew be just above the ground.” And “never do more than one run on the target. It is highly wasteful and it is likely that a further run would not be effectual, but merely costly in the pilots of your Squadron.”[xi] Sheppard’s logbook shows that from 3–5 May he flew five sorties that focussed exclusively on “British strafing.”[xii] Although Gibson’s instruction would prove sound, strike doctrine was far from uniform throughout the FAA and varied amongst squadrons, fighter wings and task groups depending on the whim and experience of leaders, with the result that pilots like Sheppard sometimes had to follow tactics that went against their conviction and training.During his two months at the Fighter School, Sheppard put in 26.9 hours solo, 1.5 at night. Evolutions included aerial combat, strafing, formation flying and navigation serials over both land and sea. The bulk of this flying was in SNJ variants but in mid-June he ‘graduated’ to the Brewster F2A-3 Buffalo. Although the obsolescent Buffalos were the subject of derisive criticism—Gibson described them as “probably the worst fighter aircraft produced by any allied country during the war”[xiii]—they nonetheless remained a second-line naval fighter, and for Sheppard they were a step up from training aircraft. He was finally flying a fighter. His classmate, Don ‘Pappy’ MacLeod, a fellow Canadian, put it this way: “In those days we thought Brewster Buffaloes were pretty good—all we wanted to do was to go 300 miles an hour. It may sound pretty silly today, but to go 300 miles an hour was our aim, so we got into those airplanes and did things like that.”[xiv] On 2 July, Gibson endorsed Sheppard’s certificate “Completed R.N. Fighter Course”, assessing his abilities as “Average”. In the typically understated parlance of the Royal Navy that meant that he was as good as most of his contemporaries, and thus had the potential to be, at the very least, a competent naval aviator. With another step behind him, Sheppard headed north to NAS Quonset Point, Rhode Island where he undertook a month of ground training before heading to NAS Lewiston in Maine where his operational training began in earnest.

USN Brewster Buffaloes cavorting over NAS Miami. Although the Buffalo had earned a terrible reputation, they were the first fighters flown by young trainees like Sheppard, and a real step up from training aircraft. Canadian Don MacLeod probably put it best: “all we wanted to do was go 300 miles an hour...” The bullied, baffed-out Buffalos gave them that chance. Photos: US Navy via Warbird Information Exchange

“Hard hitting aviation units of the British navy are training for aircraft carrier service”, declared one New England newspaper: “Units of the British Fleet Air Arm, using wallop packing American planes, are going through the tough and exacting training for aircraft carrier operations.”[xv] Sheppard found it tough and exacting, indeed. To this point, his flying record had been free of calamity but that soon changed. At NAS Lewiston Sheppard joined the FAA’s 738 Squadron, which was responsible for providing advanced training to students who had received their preliminary training in the USN system.[xvi] 738’s fighter complement was a dramatic step up from SNJs and Buffalos, and included front-line Grumman Martlet Mk Vs and Chance Vought Corsair Mk Is. Sheppard received his cockpit check-out on Martlets from 738’s CO, Lieutenant Commander John Reed, RN, on 5 August 1943, but pranged before he got airborne on his first flight. His logbook gives no detail beyond “Crashed on take-off”, however, a compilation of wartime flying accidents in Maine reveals that his aircraft swung off the runway and suffered moderate damage—Sheppard probably had difficulty coping with the Martlet V’s increased torque or its narrow undercarriage, and lost control. He got right back on the horse, and starting the next day, began a series of successful flights in Martlet Vs. On 23 August, however, he had a close call when he was forced to make an emergency landing after his aircraft sustained serious damage in a collision with another Martlet during formation flying.[xvii] Such incidents occurred on a regular basis, and during Sheppard’s two months at Lewiston and NAS Brunswick, FAA pilot trainees were involved in some 60 accidents from mishaps while taxiing, to prangs during landing and taking off, to devastating mid-air collisions. Flying was a dangerous business, and if Sheppard took anything from these experiences, it was that fortune played an important role in survival and that things happened extremely quickly in modern, high performance fighters.

The Grumman Martlet was a Godsend for the Fleet Air Arm since it was the first truly modern high performance fighter in their stable that was designed to operate from aircraft carriers. As it turned out Don Sheppard was not prepared for the Marlet’s power. Interestingly, the Royal Navy changed the names of the Grumman aircraft acquired through Lend-Lease: thus, Wildcats became Martlets; Avengers, Tarpons; and Hellcats, Gannets. To avoid confusion, they later reverted to their original American monikers. Photo: wwiivehicles.com

After accumulating 20 hours in Martlets, in the third week of October 1943, Sheppard began his operational career when he joined 1835 Squadron at NAS Brunswick, Maine. 1835 was a newly-formed front line squadron designated to join the 47th Naval Fighter Wing in the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious. The Wing concept, long utilized by the RAF, was new to the FAA. Previously, operational training and deployment had been based upon individual squadrons, but in the summer of July 1943 senior officers realized that the growth of the naval air arm had reached the point where they needed to adjust. One officer explained how “Recent visits to RAF Wings have made it abundantly clear how far we have lagged behind in the tactics of operating large numbers of aircraft, and how roughly we shall be handled by a well organised enemy if we persist in using our existing method.” In the new organization, operational squadrons were assigned to either Torpedo/Bomber/Reconnaissance (TBR) or Naval Fighter Wings. After conducting work-ups at the squadron level, they would move on to individual Wing training, and then conduct joint TBR/fighter-wing training before joining a carrier. The 47th and 15th Naval Fighter Wings—the latter destined for HMS Illustrious—were, at that time, the only wings equipped with Chance Vought Corsairs.[xviii]

These two images show Mark I and Mark II Chance Vought Corsairs cruising over Maine in 1943. The most obvious difference between the two was the latter’s “improved-visibility canopy”—it is easy to see how the pilot’s view improved from the Mk I’s ‘bird-cage’, and it also helped give the Corsair its classic look. One can also discern the Mk II’s shorter, squared-off wing. Note the Canadian Maple Leaf nose art on the Mk I. Photos: courtesy Howard King

Prangs were common at Maine as the young, inexperienced pilots learned that it was a big step to the high performance Chance Vought Corsair. Don Sheppard recalled his first hours flying Corsairs “were a mixture of trepidation, fear and excitement.” Here, a little heavy footwork on the brakes by another pilot results in a nose-over at NAS Brunswick. Photo: courtesy Howard King

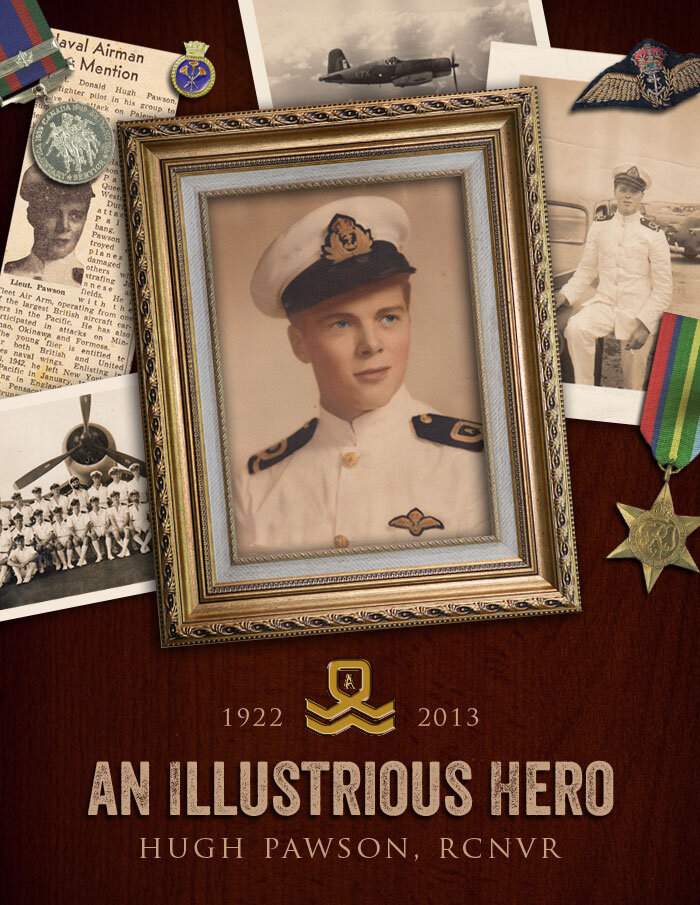

Don Sheppard became inexorably linked with the powerful bent-winged Corsair, arguably one of the most capable fighters of the Second World War. “There is nothing about a Corsair that good pilot technique can’t handle”, a USN training film boasted, “…at cruising speed [she] hums along like a sewing machine…with plenty of guts in her engine, plenty of sting in her guns.”[xix] The Corsair’s design and development are not central to Sheppard’s story, yet how it came to enter FAA service is germane. The RAF’s control over most aspects of naval aviation for much of the inter-war period meant that development of British carrier-borne aircraft had suffered badly. Consequently, at the outbreak of war the FAA was forced to combat modern enemy fighters and bombers with antiquated or deficient aircraft such as the Fairey Gladiator, Blackburn Skua and Fairey Fulmar. Help was sought through the adoption of RAF Hurricanes and Spitfires modified for carrier operations, but although they offered better performance, they did not stand up well to the rigours of flying off carriers. With its next generation carrier aircraft still on the drawing board, the Royal Navy turned to the United States to fill the void, and gladly accepted Grumman Wildcats, Avengers and Hellcats as well as Corsairs through Lend-Lease. Whereas the USN had initially rejected the Corsair as a carrier aircraft the FAA made it work and ultimately accepted some 2,012 of the fighters.[xx]Corsairs stirred varying emotions in those that flew them. In his book The Forgotten Fleet, historian John Winton explained, with “its general air of scarcely controlled menace, it inspired almost as much fear in the hearts of those who were going to fly it as in the enemy.” Winton cites the reaction of 1833’s Senior Pilot,[xxi] Lieutenant Norman Hanson, RNVR, the first time he laid eyes on what he derisively called “the bent wing bastard”: “The sentry on the hangar which held our Corsairs showed us into a side-door and we went up a stair case on to a balcony overlooking the hangar. There were these monsters. Really, they looked killers to me. They were the most dangerous bloody looking things I had ever seen. I’m not ashamed to admit it, that night I made a will.”[xxii] Sub-Lieutenant Hugh Pawson, a Canadian who later flew in 1833 under Hanson, had a different reaction, scrawling “One man’s opinion!” beside Hanson’s complaint in his personal copy of The Forgotten Fleet.[xxiii] ‘Pappy’ MacLeod thought reactions to the Corsair could be generational: he shared Pawson’s view and thought ‘sprogs’ like them who had been through the US training system had more of an affinity for the so-called “killer plane” than FAA veterans who had trained earlier on British aircraft. Perhaps the fairest and most cogent analysis of the Corsair came from Major R.C. ‘Ronnie’ Hay, a Royal Marine (RM) who was later to become Sheppard’s wing leader in the Far East and the Pacific. Hay had flown British naval fighters since the beginning of the war, and had fought the enemy in obsolescent or ill-equipped aircraft such as Blackburn Rocs and Skuas, Fairey Fulmars and early marks of Supermarine Seafires. After continually facing long odds in those aircraft, the Corsair was a revelation. It was “an absolutely marvellous aircraft”, Hay recalled:The US Navy Corsair was just the right aircraft for that war. It was certainly better than anything we had and an improvement on the Hellcat. It was more robust and faster and although the Japs could out-turn us in combat, we could out-climb, out-dive and out-gun him. By far the most healthy improvement was its endurance, with about five hours fuel in your tanks, you don’t have the agony of wondering whether or not you will make it back to the carrier.After suffering with “inadequate aircraft” through the earlier part of the war, Hay remembered “it was a real relief we were on top.”[xxiv] Like Pawson, MacLeod, Sheppard and most others, Hay grew to love the Corsair, but there is no question that the fighter’s early reputation as an accident waiting to happen sparked a degree of anxiety amongst pilots.

A number of Royal Marines saw distinguished service with the Fleet Air Arm in the Second World War, and Lieutenant-Colonel ‘Ronnie’ Hay was amongst the most illustrious. He saw action in virtually every theatre of the war, early on against terrible odds, and finished with a DSO, DSC and Bar, and an estimated four victories with nine shared (his original logbook went down with HMS Ark Royal, preventing a precise total). A skilled, inspirational and outspoken officer, Hay’s leadership and commitment to training were instrumental to the success of the 47th Naval Fighter Wing and Don Sheppard. Photo: courtesy Tony Holmes and Osprey Publishing

On Saturday 23 October 1943, Lieutenant-Commander Michael Godson, 1835’s commanding officer, checked out Sheppard on the Corsair’s cockpit drill. Once satisfied, Godson told the young Canadian he was going away for the remainder of the weekend but he wanted him to be familiar with the aircraft by the time he returned. Shortly afterwards, Sheppard took off for his first flight in the fighter in which he was to make his reputation, flying Corsair Mk I JT-146 on a one-hour familiarization flight. In the afternoon he put in another hour in JT-155.[xxv] “It was quite a shock” he recalled. “With its long nose and 2,100 hp engine the Corsair felt like you were riding on the tail of a torpedo.” “In my first ten hours in the Corsair”, he continued, “I was extremely careful not to do anything that might get me into difficulties. Each flight safely completed gave me the confidence to try further manoeuvres and expand my knowledge of this magnificent aircraft. The first ten hours were certainly a mixture of trepidation, fear and excitement.”[xxvi]

The newly formed 1835 Squadron pose with a Corsair at Brunswick, Maine. Sheppard is at right in the back row, Barry Hayter next to him. Next to Hayter is Peter King in the summer uniform. Photo via Howard King.

Over the next month Sheppard flew Corsairs on an almost daily basis. The evolutions were typical of a squadron about to embark on operations: aerial firing, formation attacks, air-to-ground attacks, aerobatics, dogfighting and low-level flying. Sheppard started out flying Corsair Mk Is, but on 18 November, took his first flight in a Mk II. This version featured significant improvements, including a shorter, squared off wing (intended to enable it to fold its wings in the cramped hangars of RN carriers but with the happy side effect of improving its rate of roll), a long-stroke oleo leg on its landing gear that reduced bounce at touchdown, and an improved-visibility canopy—the latter two modifications made the Corsair Mark II and subsequent marks much more pilot-friendly for carrier deck landings than the Mark I. [xxvii] From that point to the end of his operational career, Sheppard mainly flew Corsair IIs, with an occasional sortie in a Mk III, identical to the Mk II except that it was built by the Brewster Aeronautical Company.

A mixed formation of Corsair I and IIs flying over the New England countryside. Sheppard and his squadron mates were airborne constantly during the autumn of 1943, fine-tuning all aspects of fighter combat in preparation for operations overseas. Photo: courtesy Howard King

Sheppard’s timing in switching to Mk IIs was not a coincidence since the squadron had begun to prepare for the most challenging aspect of naval aviation, landing on an aircraft carrier. For many, this was scarcely more than a controlled crash, and ‘sprogs’ in particular were acutely aware of the inherent dangers of landing on a small, moving deck. 1835’s pilots had carried out Aerodrome Dummy Deck Landings (ADDLs) to simulate carrier landing procedures throughout November, and on the 19th the squadron flew south to Norfolk, Virginia for the real thing. On 22 November, flying JT-224, Sheppard headed out over Chesapeake Bay for the escort carrier USS Charger—it is worth noting that although the USN expressed reluctance in flying Corsairs off large fleet carriers, the RN conducted its carrier qualifications on much smaller escort carriers (CVE). “On rendezvousing with the carrier”, Sheppard recalled, “my flight of four Corsairs joined the landing circuit, confident that our shore training would allow us to land safely. On my first approach I was astonished at the number of signals I received from the batsman. Signals were coming so quickly I could only respond to about half of them. However, I got safely over the stern and landed on the flight deck.”[xxviii] It transpired that Lieutenant-Commander Godson had decided to assume the duties of Landing Signal Officer on the spur of the moment, replacing 1836’s Senior Pilot whom the pilots had practiced under previously. Despite this upset, Sheppard managed the requisite four successful carrier landings that fully qualified him as naval aviator. He went on to amass 98 deck landings in Corsairs without serious incident.

A Corsair landing on; its tail hook grasping for a wire. The Corsair’s high landing speed and long snout—Sheppard said it was “like riding on the tail of a torpedo”—made it a challenging aircraft to get on deck. Whereas the USN was initially reluctant to operate Corsairs even from its larger carriers, the FAA, desperate for modern fighters, made it work. Photo: courtesy Sheppard papers

While Sheppard sweated through his first deck landings, the Admiralty disbanded 1835. Wanting to increase the strength of operational squadrons from 10 to 18 aircraft, the FAA folded some units together, and Sheppard and four others, including fellow Canadian, Sub-Lieutenant Barry Hayter, RNVR, transferred into 1836 Squadron.[xxix] The change would have given little pause since the two squadrons had been training together at NAS Brunswick and the pilots knew each other well. Sheppard carried just three training flights with 1836 before the squadron departed overseas, but one of these, a climb to 35,000 feet, took on added ‘twitch’, in pilots’ lingo. On an identical sortie two days earlier, his squadron mate, Sub-Lieutenant J.D. “Scruffy” Wallace, RNVR, lost control of his Corsair at that altitude and plummeted to his death, presumably because his oxygen system malfunctioned.[xxx] Sheppard’s high-altitude sortie went without a hitch. Two weeks later the squadron flew to Norfolk, Virginia, where the pilots, ground crew and aircraft embarked in the escort carrier HMS Atheling for passage to the United Kingdom.[xxxi]

HMS Atheling; the escort carrier (CVE) that took Sheppard and 1836 Squadron across the North Atlantic. Atheling was similar to USS Charger, the ship upon which Sheppard met his carrier qualification. Commanded by a Canadian, Captain Ian Agnew, RCN, Atheling went on to serve in the Indian Ocean with the Eastern Fleet. Photo: Royal Navy via NavSource.org

Atheling, commanded by Captain Ian Agnew, the first officer of the Royal Canadian Navy to command an aircraft carrier, transited the North Atlantic without incident in company with the troop convoy UT-6, transporting American GIs and materiel to England.[xxxii] After arriving in Belfast on 10 January, Sheppard went to RNAS Burscough in West Lancashire for the short instrument flying course conducted by 758 Squadron. Over the next three weeks, he put in 3 hours on Link trainers and 7.50 dual hours in Airspeed Oxford aircraft, most of it under ‘the hood’, and graduated on 2 February with an uninspired grade of ‘C’. Sheppard then moved to RNAS Machrihanish at Campbeltown, Scotland, where he began intense operational training prior to embarking in HMS Victorious, the aircraft carrier that was to be his home for the next 15 months.[xxxiii]

Part Two

Although Victorious had not yet been in service three years when Sheppard joined, she had already achieved near legendary status. Upon commissioning on 29 March 1941, the Illustrious-class Fleet Carrier[xxxiv] was thrust into operations against the German battleship Bismarck, and then participated in Arctic convoys, where in the defence of convoy QP-14 her aircraft attacked the Tirpitz without success. Mediterranean convoys, Operation TORCH and other major operations followed. In 1943 she was loaned to the USN, and after various trials and inspections at Norfolk and Pearl Harbor, deployed to the Southwest Pacific where she joined a USN task force supporting landings at New Georgia in the Solomon Islands. Working closely with the USS Saratoga’s air group and senior American naval aviators, Victorious’ air department gained invaluable experience with USN carrier doctrine and procedures, and aircraft such as the Grumman Avenger, lessons that would prove critical when the Royal Navy returned to the Pacific in force in 1945.[xxxv]

After returning to the UK in the autumn of 1943, Victorious entered a major refit, which sparked a number of changes to her command team. The most significant was the appointment of a new commanding officer, who, in a carrier, had an enhanced role, planning air operations on top of his traditional duties as a captain. The new CO was Captain Michael Denny, RN, “a short stocky man with bushy eyebrows, known as a strict disciplinarian.”[xxxvi] The latter trait likely stemmed from the fact he was a gunnery specialist—or ‘square basher’—but that aside, Denny was a talented officer with plenty of fighting and planning experience. Importantly, he had served as Chief of Staff to the Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet from April 1942 until taking over Victorious, so he had intimate knowledge of the operations his ship was about to embark upon. Although stern in countenance, Denny, who was Sheppard’s CO throughout his time in the carrier, quickly gained the respect of his sailors and aircrew. Paymaster Sub-Lieutenant C.E. Stott, RNVR, who had daily contact with Denny as secretary to the air squadrons, recalled that “respect and admiration grew as the Ship’s Company got used to his methods and particularly after we had been in action.” One incident seems telling. Whilst Victorious was zigzagging as part of a task group, the officer of the watch (OOW) ordered “Port 10” instead of “Starboard 10” at one course change, with the result that the carrier ‘zigged’ when she should have ‘zagged’. The mistake was caught before the inevitable collision could occur, and the culprit was immediately summoned to see Denny who was in his sea cabin below. Stott recalls that Denny tore a strip off the OOW for endangering the ship, “but when the Commander in Chief requested the name of the officer, Denny sent his own over.”[xxxvii] Such acts enamoured captains to their crews. Sheppard displayed a similar command style later in his career which, perhaps, indicates the young officer was influenced by Denny.[xxxviii]

As commanding officer of an aircraft carrier, Denny had an additional barrier to surmount. Naval aviators are often critical of regular seagoing officers like Denny, who they derisively dubbed ‘fish-heads’ and who they accused of lacking understanding of the intricacies of aviation. Although there is some evidence of this sentiment in Victorious, it seems to have had little impact; in fact, Major Ronnie Hay described Denny as “one of the few Gunnery officers I respected”, who acted as “Father” to the aircrew.[xxxix] The officer who should have fulfilled that role was the Commander (Flying), Commander J.D.C. ‘Sam’ Little, RN, but although operational records reveal he was a competent officer, there seems to have been a generational gap between he and his young aviators. In other critical areas, particularly with the Chief Flight Deck Control Officer, Lieutenant-Commander E.W. Sykes, who was responsible for ranging, launching and recovering aircraft, Victorious ended up in great shape, although there were some initial growing pains when the ship emerged from refit. This level of skill, once honed, did much to lessen the ‘twitch’ experienced by aviators like Sheppard.

Emerging from her refit on 11 March 1944, Victorious immediately embarked upon a rigorous but compressed work-up programme. Operating ashore, her two air wings—No. 52 TBR Wing comprising 829 and 830 squadrons flying Fairey Barracudas, and No. 47 Naval Fighter Wing of 1834 and 1836 Corsair squadrons—were in the midst of their own intensive exercises. Because of tight security, few understood, although many probably suspected, there was more to this than normal training, rather it was preparation for a significant operation. Since commissioning in 1941, the powerful battleship Tirpitz and her eight 15-inch guns had been a thorn in the side of the Allies. She was a seemingly implacable being and her hulking presence in northern Norway made her the very epitome of a ‘fleet in being’, posing a considerable threat to North Atlantic and Russian convoys and preventing the Royal Navy from deploying scarce capital ships to other theatres. In September 1943, Tirpitz had been forced out of action after suffering damage in a bold attack by British midget submarines, but intelligence revealed that she would again be ready for sea sometime during the spring of 1944. Tirpitz’s anchorage at Kaa Fjord lay beyond the range of the RAF so the Fleet Air Arm was given the job of taking out the battleship.

An aerial reconnaissance photograph (above) of Tirpitz snuggled behind torpedo nets in a Norwegian fiord. The image below shows the classic lines of the battleship, and also how the high mountains and cliffs helped to shelter it from attack. As long as she remained operational, the powerful Tirpitz with her 15-inch guns posed a dangerous threat to Allied shipping that could not be ignored, and tied down British forces that could be used elsewhere.

The attack, code-named TUNGSTEN and involving the fleet carriers Victorious and Furious, four escort carriers and a screen, was initially planned for the second week of March, but it had to be delayed two weeks due to a delay in Victorious’ refit. In his report on TUNGSTEN, the force commander, Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Moore, noted that the delay “left very little time for training especially since some of Victorious’ squadrons had only recently formed.” Afterwards, Denny admitted, “These squadrons and the ship’s company were driven very hard by me during this short working-up period”:[xl] Sheppard’s logbook reflects that flurry of activity, and from the time he rejoined 1836 on 14 February until Victorious departed for TUNGSTEN on 30 March, he was in the air on an astounding 41 of 45 days. The early focus was on deck landing training—he did nine days of ADDLs, which culminated in four deck landings on HMS Ravager; another escort carrier—but serials then became closely associated with TUNGSTEN, including strike escort, air-to-air firing, fighter-defence, and formation patrols.[xli] The training culminated in a full dress rehearsal in which Victorious’ Corsairs, with Martlets and Grumman Hellcats from the escort carriers, escorted Barracudas against a full-sized mock-up of Tirpitz in Loch Eribol, which closely resembled the battleship’s lair in Kaa Fjord.

Sheppard flew his first operational mission immediately upon Victorious leaving Scapa Flow on 30 March 1944. Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft regularly patrolled the northern convoy routes to Russia, which the fleet would follow on its transit, and Sheppard carried out an uneventful Combat Air Patrol (CAP) soon after the force departed. Two days later, he became involved in the chess game that often plays out at sea. British intelligence officers knew the Germans conducted daily ‘ZENIT’ weather patrols from airfields in Norway, and they actually used the communications associated with these patrols to confirm ULTRA settings for the day, which enabled them to break current traffic. Sheppard was up on CAP on 1 April when Victorious’ radar detected the ZENIT aircraft. Controllers directed the Corsairs to within five miles of the bogey, but told them to hold their position rather than intercept. Denny reported “The Combat Air Patrol was kept hidden in the sky while the ZENIT was plotted: when clear that it would not and had not sighted the Fleet it was allowed to proceed unmolested, lest it succeeded in making a fighter alarm report, betraying the presence of the Fleet to the shore control.” No harm; no foul, and the German aircrew flew home, blissfully unaware of their near demise. Denny followed sound strategy but Sheppard’s log entry betrays his excitement and frustration: “Vectored to within 5 miles of him but CAPT. gave orders not to attack. Darn IT!!”[xlii]

In the early hours of 3 April 1944, the strike force concentrated at its launch position, 120 miles northwest of Alta Fjord. They were more than 300 miles north of the Arctic Circle, and the conditions caused some angst in Victorious. She was carrying more aircraft than designed for, which meant some had to be ranged on the open flight deck during the passage north, rather than being sheltered in the hangar. Captain Denny complained:

Cold weather on the Northward trip caused me considerable anxiety regarding the serviceability of the aircraft necessarily parked on the deck. Victorious’ flight deck is very wet in any weather, and the spray and sleet were freezing on the deck, and it is yet to be proved that Barracuda and Corsair types can stand North Atlantic winter conditions on deck with wings folded, not only as regards condition of the planes and flaps but on account of the immense amount of delicate ‘guts’ that are exposed to the elements when wings are folded. I am no aviator, but it looks thoroughly unseamanlike to me.[xliii]

Denny did all he could to keep the exposed aircraft safe and serviceable, running up their engines every two hours, and on the day of the strike, he rotated these aircraft into the warm dry hangar when the first strike ranged on deck. These measures proved effective.

Vice-Admiral Moore planned to attack Tirpitz in two waves. In each, two squadrons of Barracudas would carry out a dive-bombing attack, while Martlet and Hellcat fighters kept German heads down by strafing the flak positions as well as Tirpitz herself. Corsairs would provide top cover in case the few Luftwaffe fighters based nearby intervened. In all, a total of 40 Barracudas and 81 fighters were involved. Sheppard flew in the first strike, under the leader of No. 47 Naval Fighter Wing, Lieutenant-Commander Dick Turnbull, RN. The overall strike leader was Lieutenant-Commander Roy Baker-Falkner, RN, a Canadian who was CO of Victorious’ 52nd TBR Wing. Raised in Victoria, British Columbia, Baker-Falkner had entered the RN College at Dartmouth in 1930 on a Canadian Commonwealth Scholarship. Joining the FAA in the mid-1930s, he proved a remarkable pilot and leader, and amassed a sterling wartime record, mainly flying venerable Fairey Swordfish. Most germane to TUNGSTEN, Baker-Falkner had been in no small part responsible for easing the temperamental Fairey Barracuda into squadron service, and had done much of the detailed planning for the strike on Tirpitz.[xliv]

The two above images show the bombing-up process for Operation TUNGSTEN. In the first, Seaman Bob Cotcher lovingly scrawls a personal greeting to Tirpitz on a 1,600 lb bomb, while in the second, officers carefully fuse bombs on the flight deck of Victorious. Cotcher would undoubtedly have been pleased to learn that an estimated 16 bombs hit Tirpitz during TUNGSTEN, causing serious damage. Photos: Wikipedia

Grumman Hellcat pilots of the CVE HMS Emperor take a last look at a large scale model of Tirpitz’s anchorage before launching on Operation TUNGSTEN. Four escort carriers joined the fleet carriers Victorious and Furious in the attack on Tirpitz. The FAA regularly operated Hellcats from CVEs like Emperor, and although Corsairs trained on the smaller carriers, they seldom flew from them operationally. Photo: Imperial War Museum via ww2today.com

A Corsair begins its launch run. The combination of “figure-letter” recognition markings, in this case “7L”, was utilized for all RN carrier borne aircraft at that time. Note the two flight deck barriers in the ‘down’ position. They were controlled from a stand-up panel operated by the Flight Deck Control Officer who is visible standing to the right of the Corsair’s tail-planes near the edge of the flight deck. The sailor in the right foreground scrambles for safety with his wheel chock in hand. Photo: via Fleet Air Arm Museum

Fairey Barracuda dive-bombers from Victorious on their way to attack the Tirpitz. Although they had mixes success as torpedo-bombers, Barracudas were effective in the dive-bombing role. Note the two German destroyers observed by Lieutenant-Commander Turnbull are getting under way in the fiord below. Photos: Imperial war Museum

Smoke generators were an important element of the defences protecting Tirpitz. On some subsequent raids, advance warning of the attack allowed smoke to shield the battleship before the strike arrived, but on TUNGSTEN they were too late, leaving Tirpitz vulnerable. Photo: Imperial War Museum A 22634

Turnbull was first off Victorious’ flight deck at 0416, followed by nine other Corsairs, including Sheppard, then twelve Barracudas. The second strike launched an hour later. Baker-Falkner rendezvoused with the Barracudas from ‘The Box’, as Furious was dubbed, and then headed for the Norwegian coast. The bombers flew low, and for the first ten miles Baker-Falkner dropped a series of smoke floats to help the fighters link up.[xlv] “Owing to the slow speed of the strike, compared with that of the escort,” Turnbull observed, “the force was fairly loose and some difficulty may have been experienced in identifying friend from foe if enemy fighters had once got into the beehive.” But the enemy was caught completely unawares—in Sheppard’s words, they “caught the Germans with their trousers down.”[xlvi] Twenty-five miles from the coast, they began a long climb to 10,000 feet to surmount Norway’s mountainous terrain. Approaching the target area, the Corsairs released their drop tanks and, following Turnbull, “swept North to the entrance of Lang Fiord and round Leirbotn where two destroyers were getting under weigh; then South over the airfield where no activity was observed; round the southern end of Kaa Fiord and across the entire length of Lang Fiord. Flak experienced all round Kaa Fiord was accurate for height but astern. No fire was observed from two destroyers, which with a large tanker were lying at the head of Lang Fiord.” The Corsairs continued to provide top cover while the rest of the force started the attack. “Sighted target in position expected”, Baker-Falkner wrote in his after-action report, “then dived to keep hill cover sending all Wildcats and Hellcats down to strafe guns and target.” “This”, he reported, “undoubtedly spoilt the Tirpitz gunnery.” At 0529 he led the Barracudas into the attack. Baker-Falkner dove “towards the mountain NW of the target, pulled over the top and dived steeply towards the target itself from a height of approximately 4,000 feet. I then lost sight of all aircraft and carried out a dive from stern of the target, releasing bombs at 1,200 feet. We dived and got two direct hits. They got off some light red tracer at us, but it was nothing like the reception we expected.”[xlvii] Meanwhile, Sheppard “stooged around in high cover at 12,000 feet. I counted hit after hit, a dozen perhaps or more. The Tirpitz? It was smoking and burning…just taking it.”[xlviii] Within a minute, the Barracudas had all finished their attacks and headed home. The Corsairs maintained patrol over the area for half an hour and then, too, returned. Watching from Victorious’ bridge, Denny reported that all pilots arrived home “with a unanimous broad grin.”[xlix] The second strike was just as successful.

Circling above Tirpitz, Sheppard “counted hit after hit, perhaps a dozen or more. The Tirpitz? It was smoking and burning…just taking it.” Note the wake of a fast moving motor boat scurrying away as a huge cloud rises from an early bomb hit. The battleship suffered multiple hits, over 130 crew members were killed and 270 wounded. Most of the damage was caused to her superstructure and, despite initial assessments to the contrary, it was not long before Tirpitz was again operational. Photo: Wikipedia

They arrived home “with a unanimous broad grin.” A Barracuda lands on HMS Furious after Operation TUNGSTEN. Notice the close gap to the next Barracuda approaching to land. Because carriers had to steam into the wind while conducting flight operations, sometimes taking them off their prescribed course, tight landing and launch cycles were a must. The cruiser HMS Belfast is seen on the starboard quarter of Victorious. Photo: Imperial War Museum A 22644

The three Canucks of the 47th Naval Fighter Wing: Sub-Lieutenants Barry Hayter, Don ‘Pappy’ MacLeod and Don Sheppard pose proudly on Victorious’ flight deck shortly after TUNGSTEN. Other Canadians joined the wing later in the war, but they were the three originals. Hayter did not pilfer his Irvin jacket from the RAF; it was standard FAA issue. Photo: courtesy Sheppard papers

“They covered the Bombers”, trumpeted the public affairs caption for this image of a group of Victorious’ fighter pilots after TUNGSTEN. Standing on the right is Lieutenant-Commander Dick Turnbull, leader of the 47th Naval Fighter Wing and first off Victorious’ deck early that morning. Sub-Lieutenant Barry Hayter is next to Turnbull while ‘Pappy’ MacLeod kneels second from right in the front row. Note the variance in flying dress may be due to the fact that those in Mae Wests may have just returned with the second strike, while the others had been onboard for a while. Photo: Richard Mallory Allnutt Collection

In his history of Victorious, Michael Apps noted that most aviators on TUNGSTEN were seeing action for the first time. Nonetheless, “the proficiency and competence of the young aircrew was both significant and gratifying, for…no operation since the successful Taranto strike in November 1940 had been so carefully planned, so rehearsed and the results so decisive.”[l] Tirpitz was hit by at least 16 bombs and was left burning with serious damage. In return, casualties on the British side were surprisingly light, with a Barracuda lost on each strike, another lost on take-off, and a Hellcat that had to ditch near the fleet due to flak damage—the pilot was picked up by the destroyer HMCS Algonquin. After assessing the results of the attack, Vice-Admiral Moore triumphantly signalled the Admiralty “I believe Tirpitz now to be useless as a warship.” Perhaps, but only temporarily, and the fleet, and later the RAF, would have to return. But for now they celebrated, and one newspaper correspondent described their triumphant return to Scapa Flow: “The force which knocked out the Tirpitz came back to their base today to one of their most rousing welcomes of the war. As they rode through to the anchorage they were cheered along from ship to ship.” For Don Sheppard the entire experience must have fostered pride and, more importantly, confidence. Just a year after being awarded his wings, he had flown his first missions, participated in a significant operation and faced the enemy. As Captain Denny observed, Victorious’ aircrew had much to be proud of, but there was still much to learn.

Sheppard’s seasoning continued in a series of pinprick raids along the Norwegian coast. Involving Victorious, Furious and various supporting forces, their main objective was to interdict enemy shipping and, at the same time, stoke German fears of a major Allied amphibious assault. On 26 April, in Operation RIDGE ABLE, Sheppard flew top cover in an anti-shipping raid at Bodo, Norway. This operation reflected a pattern of employment by the 47th Naval Fighter Wing that continued for the rest of the war. Most of the time, but not exclusively, 1834 Squadron, whose Corsairs were fitted out as fighter-bombers with the ability to carry two 500- or 1,000-lb bombs, fulfilled the low-level, strike aspects of missions. In contrast, 1836 normally carried out tasks more associated with air-to-air fighting. There was some crossover, but although 1836 commonly engaged in low-level strafing during Sheppard’s time in the squadron, it never undertook bombing missions. Consequently, Sheppard’s main forte was to be aerial combat.

Weather conditions were poor for RIDGE ABLE but the strike attacked a convoy that had just departed Bodo. The Barracudas claimed hits on four merchant ships and an escort, and the largest merchant ship was reported beached and burning, with two others on fire. One flight from 1836 shot up a flak ship. There was no air opposition for Sheppard’s CAP but, like the strike, they were exposed to heavy flak. Two of 1834’s Corsairs were downed from damaged fuel tanks. Both pilots ditched and became prisoners of war. A Barracuda and a Hellcat were also lost. Later that day, just to keep the Germans guessing, Lieutenant-Commander Turnbull led six 1834 Corsairs, including ‘Pappy’ MacLeod’s, on a challenging low-level recce mission across Norway towards Sweden in terrible weather conditions.[li]

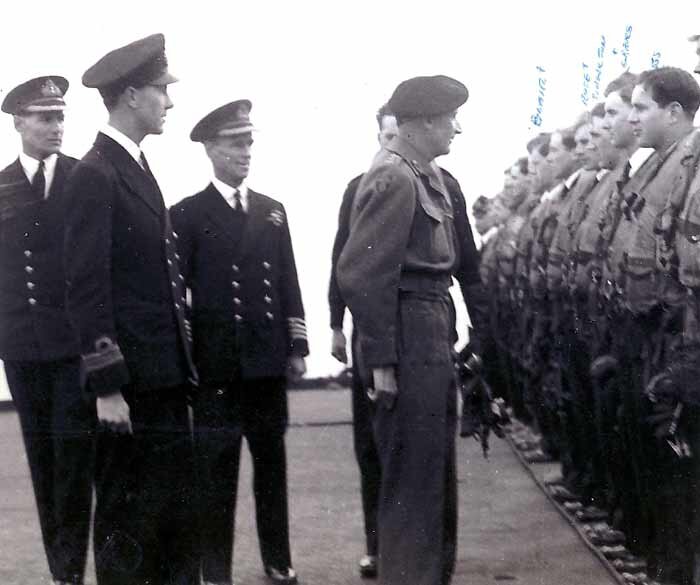

For the first two weeks of May, Victorious remained at Scapa Flow, where the Home Fleet received two distinguished visitors congratulating them on TUNGSTEN. On 8 May 1944, General Sir Bernard Montgomery, the legendary ‘Monty’, inspected Victorious’ aircrew and stopped to speak with Sheppard. It is not known what words they exchanged, but the apparent look of consternation on the faces of Victorious’ senior officers indicates concern about where the conversation might be headed. A few days later, Sheppard met an even more important personage when King George VI spent a few days with the fleet and went to sea in Victorious to observe flight operations. Barracudas and Corsairs put on an “escort and strafing show”, and Sheppard provided unforeseen entertainment when he floated on landing, caught the last wire and crashed into the barrier.[lii] No reaction from any quarter is recorded. ‘Pappy’ McLeod “rather enjoyed old George—he did a lot for the ship when he came aboard.” The King spent more time with the pilots than planned and MacLeod remembered the “guys were offering him cigarettes out of the little old rusty tins with the paint worn off. He was having a ball!!”[liii]

Monty onboard. The legendary Lieutenant-General Sir Bernard Montgomery visits Victorious in Scapa Flow on 8 May 1944. Photo: HMS Victorious Association

Monty talks with Don Sheppard—note how relaxed the Canadian appears in contrast to the nervous aviators in the image above. Captain Michael Denny is third from the left, accompanied by Commander Sam Little, the Commander (Flying), and Lieutenant-Commander Bill Sykes, the Flight Deck Control Officer. Lieutenant-Commander Dick Turnbull, leader of the 47th NFW, is obscured by the General. One cannot ascertain what Montgomery and Sheppard are talking about but the look of consternation on the faces of Denny and Little indicates a degree of concern, if not alarm. Note the pilots are literally ‘toeing the line’. Photo: courtesy Sheppard papers

Flanked by Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, the Commander-in-Chief Home Fleet, and Captain Michael Denny, King George VI strides up Victorious’ flight deck on 11 May 1944. Photo: HMS Victorious Association

Victorious departs Scapa Flow to demonstrate flying operations to the King, while the ship’s company of HMS Striker mans the side. George VI was no stranger to Scapa, having served there in battleships during the First World War. Photo: royalnavyresearcharchive.org.uk

Commander Sam Little, Victorious’ Commander (Air) explains flight deck evolutions to the King. Photo: HMS Victorious Association

The Prang

“Hit #1 barrier after catching #9 wire.” So Don Sheppard’s logbook described his barrier crash with George VI looking on. Although the Corsair’s serial number cannot be confirmed, the four images below almost certainly capture Sheppard’s prang. Although the crash appears serious, such barrier incidents were routine. In the first image, Lieutenant-Commander Bill Sykes, the Flight Deck Control Officer, is at right supervising the unravelling of the mess. According to ‘Pappy’ MacLeod, an embarrassed Don Sheppard initially couldn’t be found when it came time to meet the King, although he eventually appeared. Photos: HMS Victorious Association

The weather played a disruptive role in Sheppard’s four remaining operations with the Home Fleet. Despite Vice-Admiral Moore’s initial optimism about the damage to Tirpitz, there were concerns that she might soon return to sea, and in mid-May the fleet sortied across the Arctic Circle for a repeat attack dubbed Operation BRAWN. The strike got off the decks and was on the way to the target before being recalled due to limited visibility over Tirpitz. Sheppard explained in his logbook, “We’re going to give TIRPITZ another pounding but weather in Arctic is very unreliable. Returned because of heavy cloud over target. Fired my guns at Lodden Island for good luck.” With surprise lost, Moore took the fleet south to see if conditions would permit a strike on Narvik. Victorious launched two Barracudas for a weather recce, but one got lost. Sheppard and Sub-Lieutenant Bill Direen, RNVR, were launched to look for the missing aircraft. “Bill and I tried to find Tom Henderson and crew” Sheppard wrote in his logbook, “but weather too bad. Later heard Jerries radio that they had crash landed in Norway and burned their kite.” Moore cancelled the strike on Narvik.

On 30 May the fleet returned for Tirpitz, but—again—the weather refused to co-operate. After a report of a U-boat close-by, Vice-Admiral Moore withdrew to carry out the secondary mission against shipping off Aalesund, a focal point about 100 kilometres south of Kristiansund. RAF strike aircraft, including Beaufighters from No. 404 Squadron RCAF, had decimated shipping in this area over the previous months but had been withdrawn to southern England for Operation OVERLORD. An attack would fill this void, and hopefully keep German forces tied down. The fleet reached its flying off position on the afternoon of 1 June, and the weather was favourable—finally. A convoy was located, and Lieutenant-Commander Baker-Falkner led a successful strike by six Barracudas and 22 Corsairs from Victorious and 10 Barracudas and 12 Seafires from Furious. Sheppard gushed after his return, “No enemy a/c sighted. Bags of flak but beautiful target of 4 ships left sinking. Johnny Ball shot down (POW) & Tony Swift wounded pretty badly but made carrier.”[liv]

Sheppard’s final mission off Norway almost turned tragic. On 7 June Victorious and Furious were out on Operation KRUSCHEN, another anti-shipping strike south of Aalesund. Low cloud and fog forced cancellation of the strike but Sheppard and Sub-Lieutenant Eric Hill, RNVR, were up as CAP to guard against German reconnaissance aircraft. The fog closed in and Victorious’ homing beacon apparently failed—a common occurrence—with the result that Hill and Sheppard lost the ship, and had to divert to an airfield in the Shetland Islands. Sheppard’s initial diary entry described a fairly routine mission: “Operational CAP off Norwegian coast with S/L Hill. Weather closed in so landed at Shetland Is. Returned to ship next day.” However, when he later expanded upon the incident, he admitted it was much more nerve-wracking. “More twitch than that!!” he wrote, “Thought we would have to crash land in Norway.” Even worse, “My engine kept stopping at 400’ in cloud!!” The flight lasted 95 minutes, entirely over the sea, giving Sheppard, with his wonky engine, plenty of time to contemplate the perils of ditching into the frigid ocean. He later recalled “a very warm welcome from Norwegians and RAF chaps at Sullom Voe”—no doubt the two naval aviators were heavily fortified—but he confided “Never thought we would make it.” Others were not so lucky; two Barracudas got lost and their crews were never found. Such incidents were all too common in the northern ‘clag’ and, sadly, in July 1944, Roy Baker-Falkner and his crew disappeared under similar circumstances on a routine anti-submarine patrol.

Four days after Sheppard’s close call, Victorious departed the northern gloom for the tropics of the Far East. The carrier and her raw aviators had done well. Summarizing the series of operations off Norway, Vice-Admiral Moore praised their performance: “HMS VICTORIOUS had re-commissioned only shortly before the commencement of this series of operations and the state of efficiency reached by the ship after an abbreviated but very intensive working up period was remarkable.” More particular to Sheppard, a postwar naval staff study of the operations concluded that it was “very clear that the Royal Navy possessed at this time fighter pilots of the very highest standard in spite of many of them being comparatively new to the Service and fresh to operational work.”[lv] This, of course, was testament to their training, but it must be borne in mind that although Victorious and her air department met initial success, they had not yet been worked up to normal standards, and this became a factor in the theatres where they were headed, where challenges would be immense, and attrition high.

End of Episode One

The battleship HMS King George V plows through Arctic seas off Victorious’ starboard bow during operations with the Home Fleet. Battleships, the former kings of the seas, played a subservient role to carriers during fleet operations in the latter years of the war. However, even though their big guns were usually silent, their anti-aircraft armament played a critical role in defending carriers during air attack. Photo: Richard Mallory Allnutt Collection

As the three images below indicate, operations in northern climes—sometimes above the Arctic Circle—placed incredible burdens upon men and machinery. Sheppard and his shipmates were undoubtedly delighted to leave them behind.

About The Author

Michael Whitby is Senior Naval Historian at the Directorate of History and Heritage, National Defence Headquarters, Ottawa, where he is currently working on the Official History of the Royal Canadian Navy, 1945–1968. As well as being co-author of the official operational histories on the RCN in the Second World War—No Higher Purpose (2002) and A Blue Water Navy (2007)—he has published widely on 20th Century naval history. Edited volumes include Commanding Canadians: The Second World War Diaries of A.F.C. Layard (2005) and The Admirals: Canada’s Senior Naval Leadership in the 20th Century (2006). He is proud to be the son of two naval aviators, and his work on that subject includes co-editing Certified Serviceable – Swordfish to Sea King: the Technical Story of Canadian Naval Aviation (1995); “Fouled Deck: The Pursuit of an Augmented Aircraft Carrier Capability for the RCN, 1945–64”, Canadian Air Force Journal (Summer and Fall 2010, Vol. 3, Issues 3 and 4), and “Views from Another Side of the Jetty: Commodore A.B.F Fraser-Harris and the RCN, 1946–1964” (2012). He resides with his family in Carleton Place, Ontario.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to extend copious thanks to the Sheppard family; the staff of the Fleet Air Museum, Yeovilton, UK; Pat and Dot Whitby; Mark Styling; Tony Holmes and Osprey Publishing; Randy and Jane Hillier; Pierre Lapprand; Richard Allnut; the HMS Victorious Association and, especially, Dave O'Malley and Richard Lacroix at Vintage Wings of Canada, who all contributed time, material and passion to this project and helped bring it to fruition.

Next Episode: Navy Blue Fighter Pilot–Strike and Strike Again

Now a blooded Corsair fighter pilot, Don Sheppard, his 1836 Squadron mates and his beloved Victorious, leave the icy waters of the northern seas for service in the Indian Ocean with the Eastern Fleet at Trincomalee, Ceylon. Here, the fleet would take the fight to the resource outposts of the Japanese Empire in Sumatra. This second episode will appear in late May, 2014.

Footnotes

[i] Captain M.L. Denny, RN, Confidential Report, 15 June 1945, Donald J. Sheppard Papers. The Sheppard Papers are held by the Shearwater Naval Aviation Museum. Unless otherwise attributed, all sources are from that collection.

[ii] A depiction of Sheppard’s first aerial victory in January 1945 adorns the cover of Andrew Thomas’ Osprey Aircraft of the Aces: Royal Navy Aces of World War 2 (Botley UK 2007) and the April 2013 edition of the magazine Britain at War

[iii] Sheppard to author, 8 November 1990

[iv] Sheppard to author, 8 November 1990

[v] Stuart Soward, A Formidable Hero: Lieutenant R.H. Gray, VC, DSC, RCNVR (Toronto 1987), p. 22; and E.M. Davis, “Afloat and Ashore: Life as a Pilot in the FAA during World War II and Afterwards in the RCN” (December 1989), p. 15. Author’s collection

[vi] See Clark Reynolds, Admiral John H. Towers: The Struggle for Naval Air Supremacy (Annapolis 1991), p. 351

[vii] Sheppard logbook, September 1942–May 1943; and Captain M. Portz USNR, “Aviation Training and Expansion”, parts 1 and 2, Naval Aviation News, (1990). Sheppard’s logbook—the standard RCAF Second World War edition—is an excellent resource for his activities and, occasionally, gives his reaction to events. One has to be careful with some of the informal notations, which are sometimes difficult to marry up with precise dates due to the format of the logbook. The author also laments there was no requirement to input the starting and ending times of flights, which would have been invaluable, especially on days when multiple strikes were launched.

[viii] Donald Gibson, Haul Taut and Belay: The Memoirs of a Flying Sailor (Tunbridge Wells, 1992), p. 50

[ix] Obituary, “Vice-Admiral Sir Donald Gibson”, Daily Telegraph, 29 November 2000

[x] Sheppard to author, 8 November 1990. The emphasis is Sheppard’s

[xi] LCDR D.C.E.F. Gibson, RN, “Straight From the Horse’s Mouth”, p. 8

[xii] Sheppard logbook, 3–5 May 1943[xiii] Gibson, Haul Taut and Belay, p. 8

[xiv] NOAC Ottawa interview with D.M. MacLeod. Author’s collection

[xv] 849 Squadron Diary, Fleet Air Arm (FAA) Museum, Yeovilton

[xvi] Ray Sturtivant, The Squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm, (Tonbridge UK, 1984), p. 71

[xvii] Sheppard logbook, August 1943; and “State of Maine Military Aircraft Crash List, 1919–1989” at www.mewreckchasers.com, accessed on 24 January 2014. The latter is an invaluable correlation of aviation research.

[xviii] The National Archives (TNA), ADM 1/13997, Wing Organization. The other fighter wings were equipped with Martlets, Seafires or Hellcats, and in some cases they featured a mix of aircraft.

[xix] See the USN instructional film, “Flying the F4U Corsairs” at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R4aPk4fledU

[xx] For the Corsair’s design and development and its adaption to the RN see Barrett Tillman, Corsair: The F4U in World War II and Korea (Annapolis 2002), and Thetford, British Naval Aircraft since 1912, p. 72–73

[xxi] The Senior Pilot of a FAA squadron was the second in command.

[xxii] John Winton, The Forgotten Fleet: The British Navy in the Pacific, 1944–1945 (New York 1969) p. 66. See also, Norman Hanson, Carrier Pilot (Cambridge 1979) p. 98

[xxiii] Marginal note in Pawson’s copy of A Forgotten Fleet, p. 66. Thanks to Pierre Lapprand for sharing this and other of Hugh Pawson’s records

[xxiv] Quoted in Michael Apps, Send Her Victorious (London 1971) p. 156; and Imperial War Museum (IWM) Interview with Commander R.C. Hay at http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80013562, accessed 10 December 2013

[xxv] Sheppard logbook, 23 October 1943

[xxvi] D.J. Sheppard to James Page, January 2009. An excellent wartime USN training film on flying Corsairs is at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R4aPk4fledU. The instruction seen there would have been identical to that experienced by Sheppard.

[xxvii] Owen Thetford, British Naval Aircraft since 1912, (London 1971), p. 72–73

[xxviii] Sheppard logbook, November 1943; and Sheppard to James Page, January 2009

[xxix] Ray Sturtivant, The Squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm, (Tonbridge UK, 1984), p. 415

[xxx] Pieces of Wallace’s engine ended up in the garden of the former home of abolitionist and author Harriet Beacher Stowe. See, Dave O’Malley, “An Illustrious Hero: Hugh Pawson RCNVR” at http://www.vintagewings.ca/VintageNews/Stories/tabid/116/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/402/language/en-US/An-Illustrious-Hero.aspx

[xxxi] Sheppard logbook, December 1943

[xxxii] Agnew took command of Atheling in June 1943, whilst Captain H.N. Lay, the officer usually accorded the distinction of being the first to command a carrier, took over HMS Nabob in September 1943. Royal Navy List, April 1944

[xxxiii] Sheppard logbook, January–February 1944

[xxxiv] The RN classified Fleet Carriers as those having a hangar capacity of not less than 30 aircraft and a speed not less than 25 knots. Light Fleet Carriers had a hangar capacity between 20 and 30 aircraft and a speed between 21 and 25 knots while Escort carriers applied to all else, except MAC Ships which carried merchant cargoes as well as aircraft. Admiralty Confidential Fleet Order 2551/42, 17 December 1942, Directorate of History and Heritage (DHH)

[xxxv] For Victorious’ history see Michael Apps, Send Her Victorious (London 1971)

[xxxvi] Drucker, Wings over the Waves: The Biography of LtCdr Roy Baker-Falkner, DSO DSC RN, (Barnsley UK 2010), p. 298

[xxxvii] Correspondence between John Lenton and C.E. Stott, FAA Museum, Campaigns BPF

[xxxviii] The author’s father, LCDR Pat Whitby, RCN, served with Sheppard on several appointments, including when he was the executive officer of HMCS Shearwater in the mid-1960s. He recalls that Sheppard was a stern, no-nonsense leader with good common sense, which sounds much like Denny.

[xxxix] IWM Interview with Commander R.C. Hay

[xl] Report by Vice-Admiral, 2nd in Command Home Fleet, 10 April 1944, DHH, ADM 199/541; and CO Victorious, “Operation TUNGSTEN”, 5 April 1944, TNA, ADM 1/15806

[xli] Given the intense pace of training, accidents were bound to occur. On 10 March, Sheppard described the death of Sub-Lieutenant Patrick O’Connor, RNVR, of 1834: “Nobody quite knows what happened. He went straight in with no trace.” Sheppard logbook, 10 March 1944

[xlii] CO Victorious, “Operation TUNGSTEN”, 5 April 1944, TNA, ADM 1/15806, and Sheppard logbook, 1 April 1944

[xliii] CO Victorious, “Operation TUNGSTEN”, 5 April 1944, TNA, ADM 1/15806

[xliv] For Baker-Falkner’s career see Drucker, Wings over the Waves: The Biography of LtCdr Roy Baker-Falkner, DSO DSC RN, (Barnsley UK 2010)

[xlv] “Air Narrative” and “Report by 47 Fighter Wing Leader”, in CO Victorious, “Operation TUNGSTEN”, 5 April 1944, TNA, ADM 1/15806

[xlvi] Quoted in Apps, Send Her Victorious, p. 135

[xlvii] Cited in Drucker, Wings over the Waves, p. 308; and Admiralty, Battle Summary No 27: Naval Aircraft Attack on the “TIRPITZ”, 3 April 1945, p.

[xlviii] Quoted in Apps, Send Her Victorious, p. 135

[xlix] CO Victorious, “Operation TUNGSTEN”, 5 April 1944, TNA, ADM 1/1580

[l] Apps, Send Her Victorious, p. 13

[li] Home Fleet War Diary; and CO Victorious, Report of Proceedings (ROP), 29 April 1944. TNA, ADM 1/29627

[lii] Home Fleet War Diary; and Sheppard logbook, 11 May 1944

[liii] NOAC Ottawa interview with D.M. MacLeod

[liv] Home Fleet War Diary; and Sheppard logbook, May 1944. Sub-Lieutenants J.R. Ball and P.A. Swift, RNVR, were members of 1834 Squadron.

[lv] Admiralty, The Development of British Naval Aviation, Vol. II (London 1956) p. 231