THE LAST OF THE MANY

Former RAF pilot trainee John Mendes wrote this poignant story ten years ago. He died in 2005. We will leave the text in the present for it brings his voice back to life as he tells us about the last group of trainees of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan – Ed.

A friend has remarked that I belong to an exclusive club which has not had a new entrant for 56 years and whose remaining members are now all around 75 years old. The common bond is that they were overseas in the RAF, still learning to fly under the Empire Air Training Scheme, when World War Two ended abruptly in August 1945. We were, with no disrespect to the gallant Few who fought the Battle of Britain, the Last of the Many.

In 1939 the RAF was well aware that, in the UK, it could not train the pilots, navigators and bomb-aimers, that it would need to wage an effective air war against Germany. The airfields were wanted for operational purposes and the confidence of a trainee pilot is not helped if he is being shot at by marauding enemy airplanes. Thus was born a vast enterprise which has not so much been forgotten as never really remembered.

Hundreds of new airfields were built in Canada, South Africa, New Zealand, Australia and the then Rhodesias so that Commonwealth aircrew could learn their trade far from any combat zone. During the war years a steady stream of trained men was delivered, not just to crew new squadrons, but replace what the RAF euphemistically called wastage (over 55,000 men died in Bomber Command alone) and without them the war may have taken a different course.

The scheme was like a giant production line—the Canadians disliked the word Empire and preferred Commonwealth—and at one end it took in young men in grey flannel bags and tweed jackets with leather patches on the elbows and at the other end turned them out as sergeant or commissioned aircrew. But like any other production line it could be stopped if somebody pushed the button.

Our American allies (they also trained RAF and Royal Navy pilots) did that on 4 August 1945 at Hiroshima and five days later at Nagasaki. The Japanese surrendered on 14 August and my faded Royal Canadian Air Force logbook records that my last flight was on 20 August, a solo cross-country of 1 hour 30 minutes in the celebrated Harvard trainer. My instructor, possibly not entirely sober, said that if I promised not to do anything silly I could make my trip because I would never again fly in the RAF. He was right. The button had been pushed.

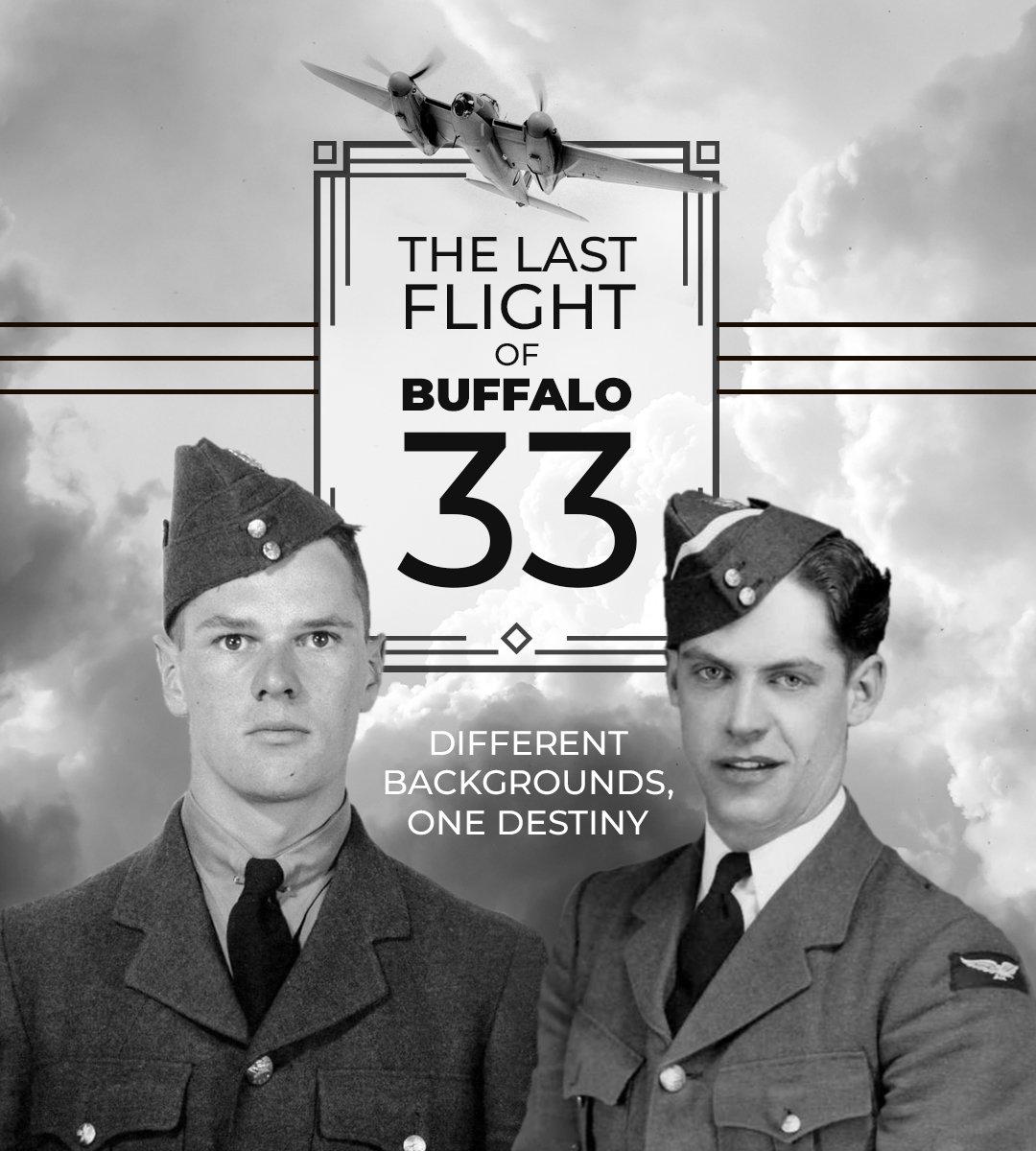

John Mendes ((left) did his Elementary Flying Training at Pendleton and his Service Flying Training at Hagersville. Since the clothing in this happy group shot seems heavy, we guess that this shot was at Pendleton in the Spring og 1945, rather than the summer when he was at Hagersville, Ontario.

The No. 10 EFTS Pendleton Quidditch Team perhaps. Three student pilots from No. 10 EFTS, Pendleton near Ottawa clown for the camera in 1945 wearing top hats made of paint buckets and riding brooms. We're not sure of the reasoning behind the photo, but one has to admit... it's unique! For the greater part of the war, Pendleton operated the de Havilland Tiger Moth, but at war's end, the school converted to Cornell trainers. Photo via Brian Mendes

John Mendes waits in the cockpit of a Cornell at Pendleton while ground personnel top up his fuel tanks. What is EXTREMELY interesting here is the Cornell in the background - number 10835. This Lend Lease funded aircraft was donated by Fleet employees to RCAF 21 October 1943 and named "Spirit of Fleet". First assigned to No. 3 Flying Instructors School at Arnprior, Ontario and then to storage 20 January to 27 June 1944. After that it was assigned to No. 1 Air Command on 15 January 1945, obviously flying from Pendleton. Today, this aircraft has been restored as it was when called “Spirit of Fleet” and is at the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum in Hamilton.

LAC John Mendes poses in the "Biggles" fashion with the “Spirit of Fleet”, the Cornell donated to the RCAF by the employees of Fleet. Mendes' log book indicates he flew this aircraft one time only - on June 11, 1945. This photo appeared in the company's Fleet Industries magazine. The latest version of the markings on the newly restored Cornell seems to have accurately included the large numeral 78 on the fuselage, but none so far seem to have the 10835 on the leading edge of the wing... hmmm. Over to you CWHM! Photo via Brian Mendes

A photo of the now restored "Spirit of Fleet II” Cornell 10835. The PT-26 Cornell was constructed by Fleet in 1943 and served with 3 Flying Instructor School, Arnprior and 10 EFTS, Pendleton. The Cornell's restoration to flying condition was especially challenging because the aircraft was in a "basket case" condition when retirees of Fleet Aerospace (formerly Fleet Aircraft) began the rebuild. The CWH Cornell is called the Spirit of Fleet II and is dedicated in memory of the 1000th PT-26 that was manufactured in 1943 by Fleet; the employees donated the 1000th Cornell to Canada's war effort. Photo: Barry Griffiths

John Mendes in on Parliament Hill Ottawa on a 48 hour pass from Pendleton. Photo via Brian Mendes

Some scenes from John's days at Hagersville, Ontario near Hamilton. Clockwise from upper left: The Control Tower, Barracks Blocks, Barracks interior and Administrative Buildings. Photos by John Mendes

The headline may just as well have read "Your Flying Career is Over". Or perhaps "We've got Good News and Bad News". At No. 16 SFTS, Hagersville, Ontario, John Mendes photographs two classmates poring over a copy of the Hamilton Spectator to read the news of Japan's surrender. One can only imagine the mixed emotions that these three experienced that day. Within a week of this date, Mendes made his last flight. Five decades later, the Hamilton Spectator used this very image as part of their 50th Anniversary of VJ Day Special Commemorative edition. Photo via Brian Mendes

By early October a dejected bunch of decidedly redundant trainee pilots had been returned to the UK at RAF Bircham Newton in Norfolk and stayed there for several months while the lords of the Air Council wondered what to do with them. Duties consisted of eating three meals a day, pub-crawling in Kings Lynn during the evenings, and on one occasion taking part in a country ramble organized by a sergeant who was keen on botany. No, I am not making this up, and we should have been happy and grateful that the war was over and we were still alive, but gratitude was a commodity in short supply at the time.

Then an air commodore came up from London in a big staff car flying a pennant. Nobody had ever seen an air commodore before (I believe the army equivalent is a brigadier) and we were herded into a hangar to hear what the great man had to say.

He made a bad start by addressing us as ‘gentlemen’ and this caused a certain amount of mirth. His face went slightly pink but he ploughed on. A great deal of money had been spent on our training, he said, and this was true. Many of us were not far from qualifying for our pilot’s brevet, he said, and this was also true. My lot were three weeks away from the long awaited wings parade, with a brass band and the instructors’ girl-friends in pretty summer dresses and flower hats, and afterwards a party.

Eventually, he got to the point. If we would sign on for three years’ additional service he guaranteed everybody would be back in flying training in a matter of days, and he made a tantalizing quarter-promise of possible commissions.

The offer was not well received. Feet were shuffled and there were whistles and even some cat-calls. The great man lost his cool. His face went from pink to purple and he shook his fist and shouted: “Very well. I will guarantee something else. Within six months all of you will be overseas in ground jobs and you will stay there until your demobilization numbers come up.” The air commodore was a man of his word. Six months later I was behind the wheel of a massive Thornycroft lorry in what is now Sri Lanka and stayed on that green and pleasant island until my demob number did indeed come up.

To be fair to the RAF, I kept my trainee pilot’s pay, and the chores were not onerous. Heavy lorries were bounced around on missions which did not seem to be terribly necessary, and as a break, officers’ wives were ferried into Colombo for shopping expeditions in delightfully over-powered Ford V8 staff cars. I did, however, get involved in a feud between two senior warrant officers.

Labourers lashed down on to the vast empty deck of my Thornycroft a small domestic refrigerator, surplus to requirements, and my orders were to take it to another RAF station about 100 miles away. On my arrival the warrant officer in charge of stores had a violent seizure. When speech was again possible he told me to get a meal and a bed for the night, and in the morning to return my load from whence it came.

A Thornycroft lorry in the employ of the Royal Air Force. Photo by Ernie Horler

For a week I happily trundled back and forth with my little refrigerator, burning fuel at seven miles to the gallon at a time when there was still severe petrol rationing at home, while two inflated egos played out their game. The episode has become a treasured memory of what the RAF solemnly called the transition from war to peace.

Today, on my lavatory wall, I have some photographs of my flying days in Canada, and must confess they arouse little interest. One or two guests have come out of the loo and asked where the pictures were taken. “But you are not Canadian. What were you doing in the RAF in Canada?”

So much for the once great Empire (sorry, Commonwealth) Air Training Scheme. Oh, well, it was a long time ago.

John Mendes, RAF