SEXY BEAST

They made aircraft tough back in the old days. Of that, there can be no doubt. Tough, eminently beautiful, and adaptable. Witness old birds like the DC-3 Dakota, the Convair Metropolitan series and the Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star. All these aircraft continue to fly and contribute decades and, in the case of the Dak and the T-33, more than 1/2 to 3/4s of a century after their first flights. Yep, they built them tough back then.

The T-33 was a trainer development of the first generation American jet fighter, the P-80 Shooting Star, and as such, saw service far, far longer than its fighter progenitor. They were simple, overbuilt in the Lockheed way, not exactly overpowered, simple to fly and, well, for the appreciative eye, elegant in a 1950s sort of way. Of all the T-33s built, the 656 CT-133s built under licence at Canadair's Cartierville, Québec factory were some of the finest, built in that solidly and unhurriedly Canuck sort of manner, equipped with a reliable Rolls-Royce Nene turbojet instead of the Allison J33 that pushed their American cousins through the skies.

As the RCAF began their decades-long rightsizing, some of these low-time, solidly-built, practicable trainers were put into storage, struck off charge and sold through Crown Assets Corporation to buyers who felt there would be a market for jet aircraft as survey platforms, research aircraft, commercial target towing ships and above all, as playthings for the wealthy business man who, having survived the Second World War as a pilot, desired to rekindle the joys of flying exotic aircraft. Entrepreneurial American buyers such as Leroy Penhall of Chino, California made deals with the Canadian government to purchase large numbers of these jet trainers at rock bottom prices. All they had to do was hire some pilots, fire them up and fly them away. Soon, former Royal Canadian Air Force Silver Stars were repainted and registered as American and scattered from California to Florida, Wisconsin to Texas.

If there is one truth in the aerospace design world, it is this: as aircraft became more sophisticated and more capable, they also became more costly. Fighter aircraft have gone from the hundreds of thousands of dollars to the hundreds of millions in the space of 5 decades. This shockingly steep cost to acquiring militarily relevant aircraft has always put second and third world air forces at a distinct disadvantage. Throughout the 1950s and even the 60s, the air forces of the derisively-named “banana republics” of Central and South America operated surplus American fighters from the Second World War and Korean War. The existence in third rung air forces of a disconnect between the desire to fly the most advanced aircraft in the world and the budget to fly only yesterday's most advanced has long been a petri dish for everything from serious creativity to hair-brained ideas and entrepreneurial overreach, or just out and out obsession.

A Royal Canadian Air Force CT-133 Silver Star. While the venerable “T-Bird” looked stolid from the side, it was a true stunner from above, with slender, tapered nose, rocketman-style tip tanks and elegant attachment of the empennage to the fuselage. This early example is configured as a target towing aircraft. Photo: RCAF

Recently, we ran a story about one John Skyrocket Morgan, one of those obsessed, former gold lamé-wearing and caped showman pilots who got it in his head that the quirky twin-boomed de Havilland Vampire would make a perfect platform upon which to build a business jet. Cajoling, convincing, conniving, contracting and cheating, Morgan managed to get one prototype completed, but it never flew. For literally decades, the former Johnny Skyrocket pursued this unattainable dream, vacuuming up his and other people's investments along the way. He had convinced himself of (and yet had demonstrated to no one else) the rectitude of his idea and potential of his so called “Mystery Jet”. The real mysteries were why he thought the idea was sound in the first place, and why he continued to pursue his dream even into the 1990s. John Morgan's brainchild and object of his obsession was last seen in the mid-90s, parked and faded in his driveway near the Reno, Nevada airport.

But the idea of re-purposing a winning design or simply designing and building a cost-effective machine for budget-strapped countries has long captured the imaginations of aviation entrepreneurs and even major players in the aerospace industry. Of the former category, the turbo-prop P-51 Mustang built by Cavalier in the 1960s is a perfect example. It looked promising enough that later, Piper got involved and “redesigned” the venerable Mustang to become the loaded-for-bear counter-insurgency/close support platform called the Enforcer. Both were classic examples of wresting failure out of a winner. P-51 purists have always been mortified by the abominations that were the Cavalier Turbo Mustang III and the Piper Enforcer. Of the latter category—the sensible, cost-effective one—the Northrop F-20 Tigershark is the ultimate example. Beautiful, capable, cost-effective, and perfect for smaller national air forces and allies, it lacked one thing… the interest of the very air forces it was designed for. At the very same time, the F-16 was on the market and allies, with or without the budgets to purchase them, wanted only the “best”—the F-15s and F-16s. Not even the endorsement of legendary fighter pilot and American icon, Brigadier General Chuck Yeager, could convince the be-ribboned, sunglass obscured generals of that market segment that the Tigershark was just what the dictator ordered.

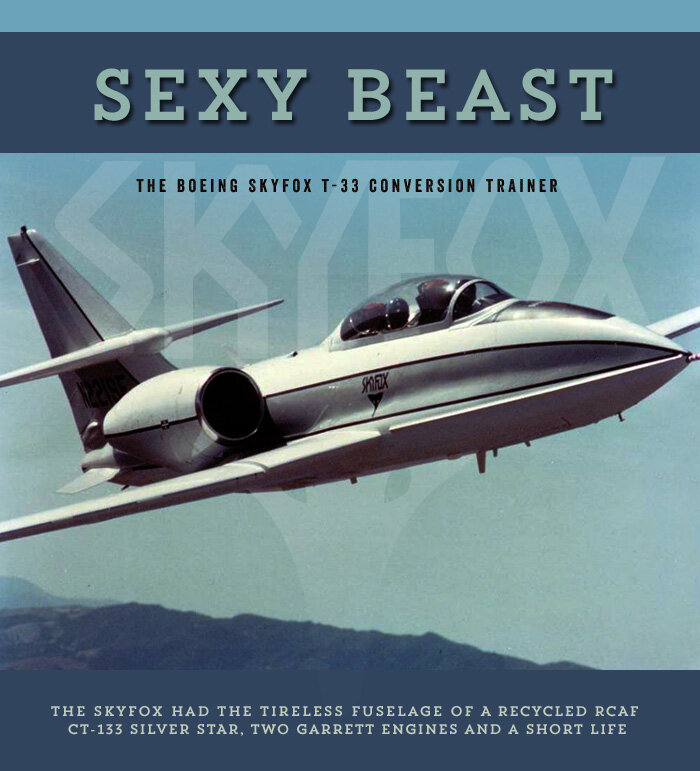

One of the least known of these first generation-to-second generation aircraft conversions was the sneakily named SkyFox—a highly modified Canadair CT-133 Silver Star trainer from the 1950s, re-engined, redesigned, even re-imagined as a second generation training aircraft, capable of competing with and replacing the USAF jet trainer of the day—the T-37 Tweety Bird. It was also intended to compete at a much lower cost (as much as 50%) with the emerging jet trainers of the day like the BAE Hawk (progenitor of the T-45 Goshawk) and Alpha Jet and even the advanced turboprops like the Pilatus PC-9.

The last of the breed. The RCAF's last operational T-Birds operated with the Aerospace Engineering and Testing Establishment (AETE) in Cold Lake, Alberta. Photo: AETE

Related Stories

Click on image

An early black and white shot of the sleek SkyFox. Photo via Dejavu

The single airframe that was destined to become the one and only SkyFox was a T-33 licence-built in Canadair's Montréal plant in 1958, with construction number T33-160. It was built for the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) as a CT-133 and given the RCAF serial number 21160. After twelve years of service with the RCAF, it was struck off charge and sold through Canada's Crown Assets Corporation to Leroy Penhall/Fighter Imports in 1973. I found an article in the Milwaukee Journal, dated 2 December 1974, entitled “Obsolete wartime fighter planes are now playthings for the wealthy.” It talks about Leroy Penhall, stating “Penhall also owns Fighter Imports at Chino, 35 miles east of Los Angeles, the only company in the United States selling war surplus jets. He started in 1971, after Gary Levitz, a scion of a Dallas furniture making family, bought a T-33 Penhall built from surplus parts. In 1972, Penhall concluded a deal with the Canadian government to buy used T-33, a plane in which US pilots trained for the faster F-86 in the early 1950s. He plunked down close to $1 million for 18 T-33s, nine of which have been resold.” It was then sold to and operated by Murray McCormick Aerial Surveys. Here we see it in an attractive green and white paint scheme in the late afternoon sun at Sacramento's Executive Airport in 1976. Photo: Steve Williams

Here we see the former RCAF T-Bird now operating for Consolidated Leasing after two years flying with Murray McCormick Aerial Surveys. Photo: Zane Adams

A bold and simple red and black paint scheme adorns RCAF 21160 as Consolidated Leasing's N12414. This photo shows the future SkyFox prototype in 1980 at the Addison, Texas airport. Photo: Zane Adams

The project was first conceived of and designed by Flight Concepts and sales efforts were conducted starting in 1983 through a company called SkyFox Corporation, but sales rights were acquired through an agreement with Boeing three years later. The rather attractive Skyfox was marketed in two forms—as a completely converted aircraft (with Boeing doing the work) or as a kit sold to T-33 operating air forces that would provide the aircraft to be converted. To replace their T-33s, the Portuguese Air Force signed an agreement with the Skyfox Corporation in the mid-80s for 20 of the conversion kits. There were no others interested in the project enough to sign a contract, so Boeing ceased development and sales efforts on the project.

The failure to sell SkyFox and the subsequent cessation of the sales efforts was followed by plenty of acrimony. A lawsuit against Boeing alleging fraud was entered by former designers and executives from Flight Concepts. US District Court D (Kansas) Judge Rogers summarized some of the facts:

This action arises from some dealings between Flight Concepts Limited Partnership and The Boeing Company concerning the production and sale of an airplane, the Skyfox, that was designed by Flight Concepts. Ultimately, Boeing was given the exclusive right to produce and sell the Skyfox. Boeing never produced or sold a Skyfox plane and subsequently terminated its agreement with Flight Concepts two years after making it. Plaintiffs contend that Boeing improperly terminated the agreement, and they seek damages in this action...

... Plaintiff Russell O'Quinn is an experienced test pilot, aircraft designer and flight engineer. Plaintiff Gilman Hill has masters degrees in geology and physics and since the 1960s has been involved in several projects concerning the modification of light aircraft. In the early 1970s, O'Quinn conceived the idea of a multirole aircraft for use by foreign nations as well as the United States. Based upon his knowledge and experience with the Lockheed T-33, he concluded that the existing airframes of the T-33s could be modified to fit the role of the multirole aircraft he envisioned. He approached the Italian government and several aircraft manufacturers in the United States, including Lockheed and McDonnell Douglas, with his ideas. He was unable to reach an agreement with the Italian government, and the aircraft manufacturers he contacted in the United States were unable to provide him the funding needed for his project. In 1981, O'Quinn met Hill and explained his concept to him. Hill agreed to invest $1.25 million in the project, and they formed a partnership named Flight Concepts Limited Partnership. Flight Concepts is a limited partnership in which O'Quinn and Hill are both general partners and limited partners. In 1982, O'Quinn began putting together a team of retired Lockheed personnel who had been involved in the test flight of the original T-33 to assist in the actual design of the modified T-33, which soon became known as Skyfox. O'Quinn and Hill subsequently formed The Skyfox Corporation. The Skyfox design replaced the single jet engine on the T-33 body with two jet engines, added a new nose and made other changes to increase the performance, range and fuel efficiency of the T-33. Plaintiffs suggest that the Skyfox is “a formidable competitor to the world's most advanced tactical fighters which cost from $10 million to $25 million per aircraft.”

The outcome of the lawsuit was in favour of Boeing, and the SkyFox faded into history. There is no doubt, however, that the SkyFox was initially a good idea, maybe even a great idea. There is no doubt, as witnessed by testing, that she lived up to her performance promises. She was also a very sexy beast, that SkyFox. So why did the design not capture the imaginations of her intended market clients—the air forces of the world that still operated the T-33? I think the answer lies in the T-33 herself. She was simply technology from the very beginning of the jet age and the prestige that so many air forces and nations so wrongly seek was not in making a smart, cost-effective upgrade to a time-tested system, but lay in purchasing what other countries wanted—the latest, most advanced technology... wisdom and economics be damned. Time and time again, trying to get one more lifespan out of a winning aircraft design has resulted in failure. It's almost an unspoken law of aerospace technology.

Strangely though, the RCAF still operates upgraded Sikorsky Sea Kings more than 50 years after first acquiring them and the USAF still operates the B-52 Stratofortress 60 years after the first one was purchased. The difference is that they are essentially slowly modified to remain relevant over the years. They were never taken off strength, modified and morphed into a different aircraft and then sold back to the same air force that was in the process of ridding itself of the type.

The SkyFox was one of those strange blips on the aerospace radar screen that turned everyone's head and then slipped off the screen when no one was looking. Just this past week, Vintage Wings chairman Todd Lemieux and I were reminiscing about the SkyFox and how it had captured a lot of attention when it flashed across the screen 30 years ago. Here for your enjoyment is all I could dig up about the SkyFox. I am sure there are great images out there, but there was little to find but grainy images of her first flights and shots of her hulk deteriorating in the Oregon sun.

Dave O'Malley

with the help of Kevin Nesdoly and Todd Lemieux

SkyFox test pilots close in on a photo ship for a promo photograph over the California desert. After completion of the conversion to the Skyfox prototype, its maiden flight was on 23 August 1983, more than 35 years after the first flight of the Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star. Famed test pilot Skip Holm was at the controls for the initial flight test at the Mojave Airport, California. The Skyfox prototype, in its roll-out colours, was white overall, with black cheat lines, and a pale grey blue trim with the SkyFox logo on each side, beneath the canopy. Photo: SkyFox

Another shot over the Mojave Desert with possibly Skip Holm at the controls. Here we clearly see her new registration N221SF for SkyFox. There are very few good photographs of the SkyFox in flight from this initial period, and none to be found on the web of its construction. We get a good view of the relatively large Garrett engines, which look not so big on a Lear Jet. The removal of the old Rolls-Royce Nene (Allison J33 engines on US-built T-33) turbojet and replacement with the two Garrett turbofans actually saved weight—some 17%! Photo: Boeing

“All right, Mr. DeMille, I'm ready for my close-up.” In these four photographs, the SkyFox sports United States Air Force markings and her SkyFox photo had been crudely painted out. This is because she was starring in a first season episode of the television series AirWolf, starring Jan Michael Vincent and Ernest Borgnine. The TV series followed the adventures of the young pilot (played by Vincent) of a secret high-tech helicopter of the same name. In the second episode of the entire series, entitled Daddy’s Gone a Huntin’, the SkyFox played itself next to AirWolf (the similarity in the names makes one wonder). The episode depicted SkyFox as a super high-tech military aircraft about to fall into Russian hands and AirWolf and its team prevented the espionage disaster. Photos: AirWolf TV Series

Another TV screen grab from the 1984–87 TV series “AirWolf” shows SkyFox touching down on a runway, shot from a photo chase aircraft. Likely, the SkyFox Corporation wanted to showcase their creation and create some buzz that would eventually benefit sales. Sadly this did not come to pass. Photo: AirWolf TV Series

The Boeing SkyFox and the venerable Boeing CT-133 Silver Star chase plane pose together in front of a Boeing hangar to demonstrate the classic Lockheed T-33 lineage of the new conversion design. Boeing had little to do with the design of either aircraft but saw potential in the trainer as a cost-effective and fairly capable trainer. There are many differences between a CT-133 Silver Star and the SkyFox, but the addition of two external engines was one of the most evident. The two Garretts weighed less than the single Rolls-Royce engine, but provided 60% more thrust on 45% less fuel. The resulting inboard space from the removal of the centre-line turbojet allowed for considerably more fuel on board, eliminating the requirement for the T-33's traditional wing tip tanks. The designers retained the mountings and fuel lines for the tip tanks in case a customer wanted more range. Photo: Boeing

The SkyFox in a later, more tactical, camouflage paint scheme banks over farmland for a promotional shot with a single test pilot at the controls, and a long centre-line test probe. Photo: Boeing

Through the mid to late 1980s, Boeing made appearances with the SkyFox at numerous air shows throughout the United States, where ordinary citizens could get a look at an exotic-looking jet aircraft with a decidedly vintage inside. Here we see it under the bright California sun at Edwards Air Force Base. The SkyFox employed about 70% of the original Canadair CT-133, but made some pretty dramatic additions with the remaining 30%—two new engines, complete redesign of the nose and tail assemblies plus a whole shopping list of standard features ranging from new aerodynamics to nose wheel steering to new fire control and braking systems. If it were not for the canopy and the basic fuselage cross-section, there was little left externally that was Silver Star. Photo: Steve Tirpak

A shot of the SkyFox from the right rear quarter shows some of the aerodynamic upgrades, including down-turned vortex generating winglets where the tip tanks once were, the leading edge root extensions (barely visible) and stabilizing strakes at the tail. This photo was taken at an air show at Will Rogers Airport in Oklahoma City in June 1987. Photo: Darrell Crosby

Walking around to the front of the SkyFox at Oklahoma City's Will Rogers Airport, we see a significantly redesigned nose which provided increased forward visibility as compared to the CT-133 Silver Star. Photo: Darrell Crosby

The SkyFox on takeoff at an air show during her Boeing sales tour. There was interest at one time to take her to Farnborough, but the interest waned. Photo via Picstopin

Today, the SkyFox resides on the ramp at Medford, Oregon’s Rogue Valley Airport, stripped of its valuable engines and sadly going nowhere, bleaching slowly in the sun. Likely the engines were sold off to realize some money out of the project. It has been there for many years as this photo was taken in 2007. Photo: Tangobar, Wikipedia

I google-mapped Medford, Oregon’s Rogue Valley Airport and it took all of 5 seconds to find the SkyFox, still languishing on the tarmac in the heat beside a T-28 Trojan. From space, we can see the engine attachment points and the leading edge root extensions. Photo via Google Maps

Looking forlorn and powerless, but more like a T-33 with her engines removed, the SkyFox is seen at Medford, Oregon Photo: Scott Slingsby at Slingsbyimages.com

Photographer Scott Slingsby is also a NetJets corporate pilot and as such gets around so to speak. One of his flights took him into Medford, Oregon where he saw the one-of-a-kind SkyFox sitting powerless on the ramp. Looking straight in the face of the engine-less SkyFox, we see one of the least pleasant angles. The old intakes from her single Rolls-Royce Nene engine are faired over forward, creating rather dumpy looking “love handles” in her lower cross-section. The altered nose of the SkyFox slopes down from the cockpit windshield, offering much better forward visibility, especially when taxiing. Photo: Scott Slingsby at Slingsbyimages.com

A close-up of the tail shows the rather sinister-looking SkyFox logo and a lot of neglect, having been marred by avian excreta. Photo: Scott Slingsby at Slingsbyimages.com

The prolonged end of a cool idea that no one wanted. Photo: Scott Slingsby at Slingsbyimages.com

Tangent Number One—Those Canadair CT-133 Chase Planes

Earlier in this story you saw a photograph outside one of Boeing’s hangars of the SkyFox sitting next to Boeing’s T-33 chase plane—a photograph designed to show the extreme makeover the T-33s of the SkyFox program were in for. While the stripped fuselage of the only SkyFox ever built lies largely forgotten on an Oregon airfield, the same chase plane, N109X, still flies a busy schedule in the next state north. Today N109X, also a Canadian-built CT-133 Silver Star, earns her keep in Boeing’s airliner test programs. She survives to this day I believe, because she is still “just a T-33” and not a new aircraft. Her proven abilities and those of her sister Boeing-operated Canadair CT-133, N416X, make her well-suited to her work... no improvements necessary thank you. Here is a photo album of images from dedicated aviation photographers and chroniclers in the Seattle area.

Boeing test pilots taxi SkyFox’s old stablemate, N109X, at Seattle. Photo: Russell Hill

Rain or shine (and I imagine Seattle has plenty of the latter), N109X still completes her workday some 55 years after she was built in Canadair’s Cartierville, Québec plant. Photo: Rick Schlamp

Two former RCAF and Canadian-built CT-133 chase planes, N109X and N416X, taking off together at Seattle. Photo: Rick Schlamp

The two Boeing chase planes come in for a landing. Photo: Andrew W. Sieber

After a full overhaul, Canadair CT-133 taxies at Seattle in a temporary state with bare metal, white and zinc chromate paint patches. Soon it will carry a new, more modern, paint scheme than the classic cheat lines she once wore for the SkyFox tests. Photo: Andrew W. Sieber

After overhaul and upgrading, Canadair Silver Star N109X lands following a pre-paint test flight. Scanning such photographic social media sites as Flickr, it is evident that ongoing testing of new aircraft types, newly completed assembly line aircraft and short production variants of old classics such as the 747, not only keeps these chase aircraft busy, but attracts some gifted aviation photographers and plane spotters to record the goings on. Boeing employs a fairly large fleet of chase aircraft, including two former RCAF Canadair Silver Stars and former USAF T-38 Talons and F-5 Freedom Fighters. Photo: Brodie Winkler

Clearly, the former RCAF trainer still has considerable value to Boeing as is witnessed by her brand new remake after her overhaul. Photo: Rick Schlamp

Former RCAF Silver Star N416X collects her gear and roars into the humid Seattle air. Photo: Rick Schlamp

Another great shot of N416X taking off. She’s looking good for an aircraft manufactured 60 years ago. She is powered by a 12,400 pound thrust Rolls-Royce Nene 10 engine. She is owned and operated officially by Boeing Logistics Spares Inc. Photo: Rick Schlamp

N416X began life in 1954 at Canadair’s Cartierville plant with RCAF serial number 21369. Photo: Andrew W. Sieber

A workday for CT-133 Silver Star N416X might include riding shotgun with a new Boeing all-cargo 747 test flight. Photo: Andrew W. Sieber

Though the SkyFox never went into production, her chase aircraft is still useful after all these years. Canadair-built CT-133 Silver Star N109X is gainfully employed as a Boeing chase aircraft, 65 years after the type’s first flight. Here we see the former RCAF “T-Bird” flying past the very latest in airliner technology as Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner brakes hard after a test flight in the rain. Chase aircraft are employed by Boeing and other aerospace manufacturers to watch, film, advise and accompany new or modified aircraft as they go through their test regimes. Photo: Tedrick Mealy

Tangent Number Two—The Lockheed TV-1/TV-2/T2V SeaStar

In researching and combing the web for information about the SkyFox, I came across the navalized version of the venerable T-33 family of aircraft—the Lockheed TV-2 SeaStar. I must admit that I had never known of its existence and had never seen one before, despite 150 having been made. What struck me was how much the design had departed from the initial P-40/T-33 airframe, and how it reminded me quite a bit of the SkyFox’s steroidal over-sizing. I include it here as a small tangent to this story. It has no bearing on the SkyFox, I just thought it was interesting.

Lockheed T-1A (T2V-1) Seastar N447TV at Salt Lake City International Airport in 1994–the world’s only surviving flyable airframe. Photo via Wikipedia

Here’s what Wikipedia has to say about the SeaStar:

Starting in 1949, the US Navy used the Lockheed T-33 for land based jet aircraft training. The T-33 was a derivative of the Lockheed P-80 fighter and was first named TO-2, then TV-2 in Navy service. However, the TV-2 was not suitable for operation from aircraft carriers. The persisting need for a carrier-compatible trainer led to a further, more advanced design development of the P-80/T-33 family, which came into being with the Lockheed designation L-245 and US Navy designation T2V. Lockheed’s demonstrator L-245 first flew on 16 December 1953 and production deliveries to the US Navy began in 1956.

Compared to the TV-2, the T2V was almost totally re-engineered for carrier landings and at-sea operations with a redesigned tail, naval standard avionics, a strengthened undercarriage (with catapult fittings) and lower fuselage (with a retractable arrestor hook), and power-operated leading-edge flaps (to increase lift at low speeds) to allow carrier launches and recoveries, and an elevated rear (instructor’s) seat for improved instructor vision, among other changes. Unlike other P-80 derivatives, the T2V could withstand the shock of landing on a pitching carrier deck and had a much higher ability to withstand sea water-related aircraft wear from higher humidity and salt exposure.

One T-1A is currently (2011) airworthy, based at Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport (former Williams Air Force Base) in Mesa, Arizona, and is being flown for experimental and display purposes. Two examples are preserved on public display in Tucson, Arizona.

Lockheed T2V-1 (T-1A) Sea Stars flying out of Naval Air Station Pensacola. It’s even harder to see the T-33 roots of the T2V than it is to see them in the SkyFox. Photo: US Navy

Tangent Number Three—Squeezing failure out of a winning design

A company named Cavalier began civilian manufacturing of the P-51 Mustang as a private high-speed aircraft and for possible sale to Central American air forces. They built a number of them right up to 1968 and even experimented with a turbine-powered variant. Like the SkyFox, they just went one step too far with a respected aircraft. The last Cavalier-built Mustang was constructed in 1968 for the Bolivian Air Force. It now resides in Canada as “What’s Up Doc!”

A Cavalier-built Mustang with a Rolls-Royce Dart turboprop—its single large exhaust exited on the starboard side. One has to admit that, despite being a monstrosity and an abomination to P-51 purists, it was oddly cool looking. This was single manufactured prototype (N6167U). The Turbo Mustang III had radically increased performance, along with an associated increase in payload and decrease in cost of maintenance due to the turbine engine, but alas... had no takers. Photo via WarbirdInformationExchange.org (a fabulous resource and forum everyone should sign up for.)

The Rolls-Royce Dart was an odd choice for a turbine conversion as it utterly destroyed the P-51’s legendary good looks. Photo via WarbirdInformationExchange.org (a fabulous resource and forum everyone should sign up for.)

Wikipedia explains: Seeking a company with mass production capability, the Turbo Mustang prototype, now called “The Enforcer,” was sold by Cavalier to Piper Aircraft in 1971. Cavalier Aircraft Corp. was closed in 1971 so the founder/owner, David Lindsay, could help develop the Piper PA-48 Enforcer.

Piper heavily modified the Turbo Mustang III prototype, unveiling the new aircraft in early 1970 as the Piper PE-1 Enforcer. Piper also modified a second P-51 airframe, which they also converted into a 2-seat, dual-control version called the PE-2 Enforcer. In this image, we can clearly see the Enforcer was capable of a heavy payload.

Loaded for bear, and no one to go hunting for. The Enforcer, like the Turbo Mustang III and the SkyFox, joined the Pantheon of great ideas, well executed that no one wanted. Photo: Piper