ROBERT HAMPTON GRAY — THE LAST CANADIAN VC

Photo: Katherine Norenius

Throughout 2010, Vintage Wings of Canada will join the Officers, Men and Women of the Canadian Navy in celebrating their 100th Anniversary. While it will not be possible to bring a ship to every major community from Coast to Coast, Vintage Wings of Canada will send naval emissaries in the form of two of our vintage naval warbirds – the Fairey Swordfish and the Robert Hampton Gray Corsair.

While the Royal Canadian Navy never operated the Corsair fighter-bomber, many RCN aviators flew the type with extreme distinction with the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy.

One such Corsair driver was Sub-Lieutenant Don Sheppard, DSC of Toronto, a pilot with 1836 squadron aboard HMS Victorious. This remarkable aviator holds the unique distinction of being the only Corsair ace in the Royal Navy - with five kills to his credit in the Pacific theatre. Don Sheppard is a highly revered fighter pilot with an unequaled career who is regarded as one of the finest pilots to have ever flown the Corsair anywhere. Today, Sheppard lives in Aurora, Ontario.

But perhaps the most widely known Canadian naval aviator from the Second World War is Lieutenant Robert Hampton “Hammy” Gray, VC, DSC, who was much loved by his 1841 Squadron mates aboard HMS Formidable and who was highly regarded as a flight commander and aggressive pilot. It was, however, the manner of his death that makes him so well known to Canadians. Gray died in the final few days of the war when the Corsair he was flying was shot down as he was attacking a Japanese warship in Japanese home waters. The facts are well known and yet still the focus of speculation and interest more than sixty years after his death

Here, Don MacNeil tells us of Gray's life and final moments.

Today, fourteen statues and busts stand on Sappers' Bridge near Ottawa's Parliament Hill. The Valiants Memorial is a collection of nine busts, five statues and a large bronze wall inscription that reads, “No day will ever erase you from the memory of time” (in Latin: “Nulla dies umquam memori vos eximet aevo”), from The Aeneid by Virgil.

The Valiants Memorial reminds us how war has had a profound influence on the evolution of Canada. The fourteen individuals featured in the memorial are celebrated for their personal contributions, but they also represent critical moments in our military history. Presented together, they become a kind of pageant of our past, showing how certain key turning points in our military history contributed to the building of our country. The memorial is therefore intended to acknowledge and honour the role that military participation, and the men and women who contributed to that participation, have had on nation building. One of those statues is the likeness of Canada’s last Commonwealth Victoria Cross recipient, Lt. Robert Hampton Gray.

Who was Lt. Robert Hampton Gray? Why was he posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross? Many today have never heard of the Victoria Cross and many have no understanding of its importance today. This short essay attempts to answer these and many other questions about the life and death of Gray.

Born in Trail B.C., to John Balfor Gray a Boer War veteran and his wife Wilhelmina Gray of Listowel, Ontario, Robert Hampton (Hammy to his friends and family), was the oldest son in a family of three, with a brother Jack and sister Phyllis. John Gray, a jeweller, later moved his family to Nelson B.C. where he became well known in town and was elected to town council.

Looking from the staircase that descends beneath Ottawa's Sappers' Bridge to the Rideau Canal, we can see the pantheon of great Canadian heroes known as the Valiants. Robert Gray is the bronze bust at the left near the banner. Next to him is the bust of another Canadian airman who was awarded the Victoria Cross - Andrew Mynarski of the RCAF. Beyond stands the famous former-railroad hotel - the Chateau Laurier. This hotel played an important role in the movie Captains of the Clouds about the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan - under which, Gray received his Service Flying Training and Naval Aviators wings. Photo: Vincent Alongi

A close-up of the bronze bust of Lt. Robert Hampton Gray, RCNVR. Photo: The Valiants Memorial

Related Stories

Click on image

Robert Hampton Gray, 28 years old at the time of his death, was a courageous and respected leader of men in combat.

Hammy, a good student in high school, liked politics and literature. He was relaxed, casual in his dress and would slouch rather than sit. Gentle of countenance, he loved the ironic and enjoyed mimicking anyone, he was irreverent and liked to express mock disgust or outrage.

In the fall of 1936 he entered the University of Alberta and later transferred to the University of British Columbia for Pre-meds. At U.B.C. he was a fraternity house manager and worked on the university yearbook for 1941. Abruptly at the end of the 1940 university term he decided to enlist in the armed forces with the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve (RCNVR) as a rating on loan to the Royal Navy as a prospective officer cadet. He was one of 150 from across Canada and by war's end, 28 had been decorated for bravery. Eighteen of these men never made it home.

Hammy sailed with the first 74 recruits to England on the 13th of September, 1940 for training at HMS Raleigh. In December, the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) offered Hammy a faster route to war with an invitation to join the FAA for pilot duties first at HMS St. Vincent, Gosport. He was to find out that the road to an officer’s commission was a long one of hard training and discipline.

In March 1941 his elementary flying training started on the open cockpit monoplane known as the Miles Magister. This was carried out at No. 24 EFTS located at Luton near London. Flying for the first time on March 21st he wrote home about his love of flying and how pleased he was with his decision to join the Fleet Air Arm.

In June of 1941, Gray was sent to Canada to complete his Service Flying Training on the Canadian built Harvard 2 trainer at No. 31 Service Flying Training School in Kingston, Ontario. He disliked what he thought was a childish emphasis on routine and discipline at this school but changed his attitude when he began to fly Fairey Battle trainers. By Sept. 1941 Hammy was commissioned as a Sub Lieutenant and graduated as a pilot – he would soon be off to war but would have to wait three long years before he saw enemy action.

Gray began his Elementary Flying Training on the Mile Magister basic trainer at Luton's No. 24 EFTS. Photo: RAF

Hammy (at left in inset photo) crossed back over the Atlantic to do his Service Flying Training at No. 31 SFTS in Kingston, Ontario, Canada. To this day, the former BCATP base is the site of the Kingston Airport, where a memorial to Robert Hampton Gray (bottom centre) stands beneath a Harvard 2 gate guardian. Photo: Will S. at Flickr

He was first posted to South Africa in May of 1942 to the newly formed 789 Squadron. 789 operated Albacores, Sea Hurricanes, Swordfish and Walruses on support duties from Wingfield, South Africa. 789 Squadron was positioned there to protect against Imperial Japanese Navy fleet advances through the Pacific. After the American success at the Battle of Midway, this threat to South Africa eased and Hammy was re-assigned to Kilindini, Kenya with 795 Squadron. In Sept. 1942 Hammy was appointed to 803 Squadron flying Fulmars from Tanga and then posted to 877 Squadron.

On December 7th, Hammy’s squadron was posted to HMS Illustrious, sister ship to HMS Formidable, the ship that would later become Hammy’s final home. He was promoted to Lieutenant on December 31st 1942 and assigned to 877 Squadron flying Sea Hurricanes as second in command.

On August 6th, 1943, Hammy was posted back to England and became the senior pilot of 1841 Squadron. After four long years of training and operational flying he was finally going to see action as 1841 Squadron was assigned to HMS Formidable which was about to undertake further attacks on the Nazi battleship Tirpitz as part of Operation Goodwood.

The first Tirpitz attack, planned for Aug. 21st, was cancelled due to poor weather and aborted again on the 22nd due to heavy cloud. On the 24th, 18 Corsair ground attack aircraft along with 16 Barracuda aircraft loaded with bombs were launched along with six other Corsairs which were loaded with armour piercing bombs. German anti-aircraft gunners ashore and on the Tirpitz and on other escort vessels were ready and waiting.

Hammy, in his first combat, lead his flight of Corsairs straight down at point-blank range to suppress the anti-aircraft fire and draw it away from the slower attacking Barracudas. This attack did not succeed in sinking Tirpitz and resulted in heavy British aircraft losses.

Formidable launched another attack on the 29th with Hammy again leading a daring close-in attack while receiving a direct 40 mm hit in the rudder. He flew back to the ship and orbited for 45 minutes in a brave show of airmanship waiting his turn to land rather than disrupt the landing pattern. With his gun camera film showing extreme close-ups of the anti-aircraft guns, he was heard to say that "some dumb Canadian needed a good talking to". He was awarded a Mentioned in Despatches (MID) "for undaunted courage, skill and determination in carrying out daring attacks on the Tirpitz".

HMS Formidable in her North Atlantic dazzle paint scheme. Photo: RN

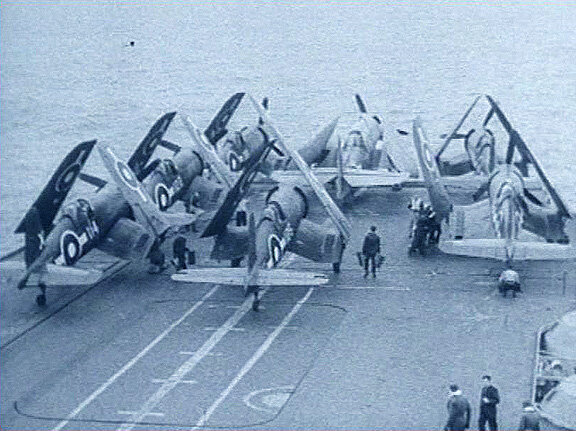

Corsairs of Formidable's complement arrayed for action during operations in the North Atlantic - note Temperate Sea scheme camouflage. Photo: RN

The only photograph that we have yet seen showing Robert Gray flying - or rather launching from the escort carrier, HMS Rajah, in 1944. With the Corsair painted in camouflage and having a full roundel on her side, this is in the North Atlantic colour scheme. Source: Major A.E. Marsh RM (Ret'd). Fleet Air Arm Negative: CRSR/43.

By the spring of 1945, operations in the European theatre of war were winding down after the invasion of Europe and allied success in re-occupying much of Europe. Formidable was re-assigned to operations in the Pacific and the final drive to defeat Japanese forces. At this time, 1841 and 1842 Squadrons were refitted with 20 new F4U-1D Corsairs while other squadrons aboard now flew 12 Grumman Avenger torpedo bombers and 6 Hellcat fighter aircraft.

At the end of June 1945, Formidable and four other British carriers sailed from Sydney to join the USN Third Fleet under U.S. Admiral "Bull" Halsey. As the allied fleet pushed towards the islands of Japan, they fought against Kamikaze aircraft while launching strikes on Japanese airfields, warships and other strategic military targets. Matsushima Military Airfield was a key target assigned to the aircraft of HMS Formidable.

This photo of Corsairs running up on HMS Illustrious' deck shows Pacific theatre markings - all blue paint and white centred roundels with American style bars. Photo RN

The only photo yet to be found that shows the original Corsair number 115 of the Royal Navy’s 1841 Squadron. It is generally accepted that No. 115 was not “Hammie” Gray’s usual aircraft, as his was unserviceable at the time that he launched from Formidable on that fateful day. Here we see 115 chained and battened down for inclement weather enroute to some action - with engine cowl and canopy covered in canvas to protect them from the effects of salt spray. Inset - the squadron crest for 1841 shows an eagle preying on a dragon above the waves - a heraldic depiction of Robert Hampton Gray’s final action when he pressed home his attack on the Japanese escort ship Amakusa, sinking her in Onagawa Bay. There are some who believe that 115 was not the aircraft he flew that day and others that insist that the markings were slightly different (the numeral "1" before the roundel and "15" after). Others insist that the serial number was not KD658. Still others insist that his personal aircraft was 119. This is possible too, but until the day that incontrovertible proof is offered as to different markings, we will fly our own Corsair in these markings - it will be easy to make a change. Regardless of long-lost records which may or may not support these claims, our Corsair will always be a flying tribute to Gray.

The immediate aftermath on the deck of Formidable as Hammy and his crewmates battle fires and chaos following a Kamikaze hit. Photo RN

A dramatic photograph from the forward deck of HMS Formidable shows her crew dealing with the chaos of the Kamikaze strike. Forward of the island, stands a Corsair that might be Corsair 115 safe from the fires and destruction on the after deck. If this is No. 115, it would still not be the airframe flown by Gray as that aircraft (KD658) was delivered from baby flattop HMS Arbiter the next month. Perhaps this one was lost or damaged after the date of the Kamikaze strike and before delivery of KD658 or received a new number later. RN photo

This photo showing the aftermath of a Kamikaze strike on HMS Formidable two months before Gray’s final flight. It also shows our team the placement of the ship deck code (the letter “X” was worn by all aircraft aboard Formidable). As well, there seems to be no set position for the Royal Navy titles aft of the roundel. In other RN photos in the Pacific Theatre, these titles are in varying positions. The ship deck code was also painted on the deck of RN carriers to prevent returning aircraft from landing on the wrong carrier.

For the first time (that we know) we have flying images of the Corsair that our Corsair is replicating - number 115. Frames (actually screen captures from a DVD) from a film crew's "B-roll" taken in the Pacific at the time Robert Hampton Gray was aboard show Corsair 115 lifting off from HMS Formidable's deck. Depending on the date when this photo was taken, this particular Corsair 115 may or may not be serial number KD658. The smoke plume at the edge of the deck is quite possibly a wind indicator. Images via Mark Peapell

A nice action shot of Corsair 120 just lifting its tail wheel off the deck as her pilot thunders down the flight deck. There were two Corsair-equipped squadrons operating from Formidable at the time - 1841 and 1842. The propeller hubs of 1841 Corsairs were painted a dark colour (blue or possibly red) while 1842 Corsair had white hubs. This would make 120 a Corsair with 1841. Images via Mark Peapell

A shot showing flight deck maintenance in progress on HMS Formidable in the summer of 1945. The aircraft in the background is a Hellcat (119). Corsairs operating from Royal Navy carriers had the tips of their wings clipped to enable hangar deck stowage on the smaller British carriers. The wing of the Corsair in the mid-ground clearly shows this feature. Images via Mark Peapell

In this shot down the elevator shaft aboard HMS Formidable, an 1842 Squadron Corsair (146) gets plenty of attention from maintainers in the hangar deck. Sitting on the wings are the large flight deck chocks that were used to prevent movement on a heaving deck. Images via Mark Peapell

Six of Formidable's complement of Corsairs and an Avenger are seen tied down on the forward deck. The wing on the Corsair at right is being folded by hand . . . the deck crew is providing the manpower. The centre Corsair is under power with the handlers walking alongside with the chocks. As the Corsair wings don't have the safety struts installed, we can only guess that the one Corsair suffered some sort of hydraulic failure which resulted in the wing dropping. Images via Mark Peapell

Corsairs (mostly 1842 Squadron with white propeller hubs) and Avengers aboard HMS Formidable warm their engines as they get set to launch an operation. Photo: RAFImages via Mark Peapell

A packed deck aboard Formidable shows Avengers, Corsairs, and Hellcats. Images via Mark Peapell

On the night of August 8th, Admiral Vian, leader of the British forces, briefed Squadron Commanders not to take any unnecessary chances in their attacks on Japanese targets, as the atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima and Japanese capitulation was expected at any time. Also, the senior officers knew but could not disclose that another A-bomb was to be dropped the following day on Nagasaki. Pilots were told to limit staffing or bombing runs to one pass to limit risks.

At 0835 on August 9th, Hammy Gray climbed into his aircraft and prepared to lead his flight of seven Corsairs in the attack on Matsushima airfield. At the last minute, Chief Petty Officer Dick Sweet was sent to Hammy’s waiting aircraft with an urgent message that Matsushima Military Airfield had been heavily bombed earlier and was thought to be out of commission and if so he was to seek other targets of opportunity. Hammy lead his flight to Matsushima airfield, confirmed the damage and the need to attack other targets such as Japanese ships he had seen anchored in Onagawa Bay.

Flying from the mainland side at approximately 10,000 feet Hammy turned his two flights towards Onagawa Bay to avoid anti-aircraft fire. He dove his aircraft in order to get down to sea level for the short bombing run at his chosen target. All Japanese ships in the bay were heavily armed and prepared for an air attack. Additional anti-aircraft positions dotted the surrounding hills creating a killing zone for attacking Allied aircraft.

Hammy headed for the largest ship in the harbour, the ocean escort vessel Amakusa that was about the size a small destroyer. As he leveled out for his bombing run, one of his two five-hundred pound bombs was shot away by a hail of cannon and machine gun fire from Amakusa, Minesweeper 33, the target ship Ohama (a target ship being a gunnery training vessel) and Sub Chaser 42. Hammy released his other bomb and scored a direct hit on Amakusa. This bomb penetrated her engine room instantly killing 40 sailors (including all in the engine room) and triggering an the explosion in the aft ammunition magazine. This massive explosion resulted in the sinking of Amakusa in just minutes. Hammy’s flight members then recounted seeing his aircraft enveloped in smoke and flame. They reported that his aircraft, at an altitude of only fifty feet, rolled to right into the sea in an explosion of debris and water. The aircraft was never seen again.

IJN Amakusa was an Etorofu Class escort (Seen here in this painting by Takeshi Yuki scanned from "Color Paintings of Japanese Warships"

Also laying heavy anti-aircraft fire on Gray and his men was IJN Ohama an anti-aircraft gun platform. Image via SnowCloudInSummer

The following is a description of the attack as recounted by Hammy’s youngest surviving flight member in a recent letter to the author.:

"The draft of my letter, written on Christmas Day 1945 and sadly not shown to my parents, said I saw smoke coming from a Corsair’s starboard wing. That matches the "flick to the right" report. I also had a vivid memory of seeing one Corsair about 300 yards ahead of me when an explosion blew off the starboard wing at the hinge. I can see it now, the wing separated from the aircraft. Naturally I am aware of false memory.

Storeheill [Hammy’s wingman] should have been ahead of me. Perhaps he jinked to starboard. Blade, (number seven in the formation, I was number six), reported that he dived rather faster than the others and passing over the stricken destroyer saw two aircraft ahead, one with flames from the port wings (Hammy inverted?), which crashed. Blade should have been behind me. He might have seen me behind Hammy, missing a jinking Storheill. I was too inexperienced to jink. If Blade had been in front of me I would have seen him and Hammy."

IJN Amakusa under attack by Robert Hampton Gray. Much-loved Canadian aviation artist Don Connolly depicts the final moments of Gray's attack. Image: Don Connolly

After someone keyed their radio mike saying ‘There goes Hammy", his Second in Command, Sub. Lt. MacKinnon, took over as Flight Leader and launched two more attacks until the two flights exhausted their bombs and cannon ammunition on other targets in the bay. One hundred and fifty-eight Japanese servicemen were killed (71 on Amakusa alone). Most of the warships in the bay were sunk (this includes Ohama), destroyed or badly damaged. Japanese accounts of the battle talk of the valour demonstrated by Commonwealth pilots as they pressed home their attack.

Following this battle, the senior officers under British Admiral Vian met to discuss a suitable honour to recognize the bravery of Lt. Gray. Since he had already been Mentioned in Despatches and had been recommended for a Distinguished Service Cross, it seemed that there was only one suitable award to honour this outstanding leader, pilot and brave Canadian – the Victoria Cross, the highest Commonwealth award for gallantry.

The Victoria Cross was created by Queen Victoria during the Crimean war to honour servicemen for the most conspicuous bravery or some daring or pre-eminent act of valour or self-sacrifice or extreme devotion to duty in the presence of the enemy. From 1854 to 1954 there have only been 1345 Crosses awarded of which 96 have been to Canadians and only 16 during the Second World War. Hampton Gray’s was the only one awarded to a member of the Royal Canadian Navy or any other Canadian navy pilot and the last to be awarded to a Canadian as the Canadian Government had just recently created its own version of the Victoria Cross - with the words "For Valour" changed to their Latin equivalent to avoid French/English bilingual issues.

In Onagawa Bay, next to a memorial to those Japanese servicemen killed on August 9, 1945 stands the only foreign military memorial on Japanese soil - a memorial to Canada's Lt. Robert Hampton Gray which was placed by the Japanese military to honor what they saw as an extreme act of heroism. On a recent visit to Japan by members of the Canadian warship HMCS Ottawa, a wreath was placed at this memorial by the Captain and ships company in Lt. Gray’s honour.

In 2006, officers of the Canadian Navy's HMCS Ottawa placed a wreath at the memorial to Robert Hampton Gray on the shores of Onagawa Bay in Japan. Gray’s marker is the only memorial dedicated to a member of any Allied armed force on the Japanese main islands. Gray’s aircraft crashed into the waters in the background, killing him in the final days of the war. DND Photo

Somewhere beneath the sparkling and now peaceful waters of Onagawa Bay, Miyagi Prefecture, Japan lie the mortal remains of Robert Hampton Gray and the wreckage of his Corsair.

Throughout 2010, Vintage Wings of Canada will take its Gray Ghosts program including the Robert Hampton Gray Corsair across Canada to help the Canadian Navy to celebrate its 100th Anniversary. Stay tuned for a full schedule of events. Photo: Peter Handley

Of course, the Robert Hampton Gray story is only just a small part of the incredible contribution made by Canadians in the Fleet Air Arm. After completing this story, we recieved a detailed letter from one of our readers, Mark Peapell from Halifax. He rightly points out that our tribute to Gray is much deserved, but that there are many other compelling stories. Here are a couple of extracts from his letter:

“Due to the heroic nature and subsequent award of the VC, the story tends to gloss over the other players in the story. HMS Formidable was comprised of a very diverse ships complement including Canadians, New Zealanders, Norwegians, Dutch as well as British pilots and crew. From May till the end of the war there were 6 Canadian pilots assigned to Formidable, with only 2 surviving the war,

The hazardous nature of the mission not only from the enemy, but carrier operations accounting for these losses. In fact most of Gray’s fellow countrymen, had similar operational time as he did, including the Tirpitz raids and the transfer to the Pacific fleet.

Canadian Corsair operations are an overlooked part of the Gray story. The first Canadian killed in action over the mainland Japan was a Canadian Corsair pilot, as was the last Canadian Naval war casualty (Anderson), as he attempted to land his aircraft back on Formidable after Gray’s loss.

The other Canadian side note to the Formidable story is the assignment of Hellcat aircraft to Formidable in July 1945, for the final operations against the Japanese home islands.“The other Canadian fact less known, that the cruiser HMCS Uganda was assigned to the same battle group as Formidable, until they decided that they were going home!

The British Pacific fleet is very much known as the “Forgotten Fleet”, and subsequently there has been very little information written on the subject. There is an interesting book written by the members serving on the Formidable called a” Formidable Commission “ which was published in 1947.

I do also have video of Gray’s aircraft 115 taking off from Formidable as well as deck shots, including Atkinson’s Hellcat. To distinguish the Corsairs of the two squadrons, 1841 and 1842, the center propeller dome was painted different colours, 1841 was a dark colour either red or blue, while 1842 was white. You can see the differences in the various few pictures as well as the video I have.

One final point is that you have mis-identified one of the pictures of Corsairs lined up for take –off as being on Formidable, this is however HMS Illustrious. The two dead giveaways are the white center deck markings. All British carriers hand a call sign painted on their decks as well as different styles of center deck white lines. In Formidable’s case, it was a solid white line, where Illustrious is a series of dashes. In most cases it is the easiest way to determine the carrier, rather than relying on someone else’s interpretation.

The other dead giveaway is that Formidable never carried any Corsairs with camouflage and SEAC roundels and bar. These camouflaged aircraft would be the earlier Vought built Corsair‘s. When Formidable transferred to the Pacific, it took on a new complement of Corsairs which were at this point now being built by Goodyear in Akron Ohio. All Akron built aircraft were delivered in the Gloss sea blue colour scheme. [the Vintage Wings of Canada Corsair is a Goodyear-built aircraft - ed.]

As far as I can determine, all British Corsairs shipped out to the Pacific, carried the standard roundels with the red center) Once the aircraft was in theatre, either by its own carrier or buy escort carrier, it was painted in the SEAC bar and star. This was generally done by the MONAB’s (Mobile Navy Air Base) based near Sydney, Australia then put back on a ship to be transferred to the fleet at Manus. This does explain the difference in size and placement of the roundel and bar. The individual aircraft side number was done on the ship itself. In Formidable’s case, not only the Kamikaze attacks, but a subsequent fire in the hangar, meant a huge turnover of aircraft and the need to replace aircraft was always a priority, throughout its BPF service.