HURRICANE BIPLANE

There was a time before computer modelling when all sorts of concepts were given an aerodynamic chance at life. It was a time of great experimentation and excitement. The aviation world was full of some pretty strange one-off aircraft that were either outright failures or before or after their time. In the case of the biplane Hurricane, the builders first designed and constructed a proof-of-concept airplane—a tiny aircraft that could begin its flight as a biplane and end it as a monoplane.

If you do any amount of research or web-surfing on the internet about Second World War aviation, or any type of aviation for that matter, you will chance upon some fascinating facts and some fairly obscure images from time to time. If you are like me, you have a folder in your electronic files into which you dump these facts and images, with the hope of someday following them through to a story befitting their obscurity and unique qualities. I call my folder Random Beauty, and it is full of some pretty strange aviation material, from which many stories are nurtured and eventually harvested.

Many years ago, I came upon an image of a Hawker Hurricane, photographed from below as it banks gently away to the left. What made this image so compelling for me was the fact this was no ordinary Hurricane—it had a second and identical wing! It was a Hurricane Biplane! I was aware of all the fabulous Hawker Biplanes which led up to the development of the monoplane Hurricane itself—Nimrod, Audax, Hind, Fury, Hart, etc.— but I was never aware of this two-winged Hurricane. Over the past three years, I have dumped additional images into my Random Beauty folder and looked to someday putting together a story about it and its development. That day has come.

By the beginning of the Second World War, in late 1939, the writing was on the wall for the biplane combat aircraft—both fighters and bombers. Though many biplanes were still in use on both sides, manufacturing was steadily drawing down as designers and governments turned their creative talents and procurement budgets to the monoplane. The reasons why biplanes existed at all were simple. First, materials strengths in the first 30 years of flight did not allow for highly manoeuvrable monoplanes. Secondly, these early materials strengths led to a box-structure for wings to lift the heavy, underpowered engines of the day. The advent of better steel and aluminum structures spelled the end of the need for these lightweight box structures.

Soon, the monoplane was not just ascendant, but the only way forward. Biplanes, for the most part, were used for liaison and training activities in the last years of the war. There were exceptions, but the days of the military biplane were over. In the case of the fighter aircraft, three things were of absolute necessity—manoeuvrability, strength/payload and speed. The biplane could often match and even surpass the monoplane on the first two of these requirements, but not the last and most important—speed. The addition of a second wing, and its attendant struts and wires, made for increased lift but extra drag. An aircraft built with two main wings was capable of lifting up to 20 percent more weight than a monoplane of similar wingspan and weight. Traditionally then, biplanes were given shorter wingspans than the equivalent monoplane, which provided the benefit of greater manoeuvrability in the roll. A biplane typically produces more drag than a monoplane, especially as speed increases and each wing of a biplane has a negative effect on the aerodynamics of the other wing. This increase in drag gave limits to the top speed of late model biplane fighters, despite their other positive qualities.

It was those positive qualities of increased lift that led some designers to continue to consider the biplane configuration for special duties. In the case of the defensive fighter, called upon to scramble from a field and get to or above an attacking enemy as soon as possible, the lift provided by a second wing was definitely missed, but once the battle was engaged, a higher speed than the enemy was an advantage a fighter pilot would never sacrifice. Some designers, such as those at the small Manchester-based aircraft components and light aircraft manufacturer called F. Hills and Son Ltd, played with an idea of a jettisonable second wing (a slip wing) that would give more wing area during takeoff and less during flight.

F. Hills and Son gained valuable aircraft construction experience by license building a small wooden general aviation aircraft called the Praga during the 1930s. The Praga was built largely by ČKD-Praga in Czechoslovakia, but of the more than 300 built before and after the war, 28 were constructed by F. Hills and Son (Hillson). The aviation knowledge gained by Hillson on this small aircraft gave them the experience they needed to attempt a concept for a “slip wing” fighter. First they would build a proof-of-concept slip wing aircraft and then apply this knowledge to no less an aircraft than the Hawker Hurricane.

The Hillson Praga E-114 “Baby” built in Manchester. F. Hills and Son Ltd gained valuable experience building light aircraft when they were licensed to construct the civilian Baby aircraft by Czech aircraft builder ČKD-Praga. The Praga was a high wing, cantilever monoplane seating two in a side-by-side cabin. This Praga (G-AEON) was sold to an Australian and re-registered as VH-UVP and is photographed here likely at Barton Airfield, Manchester. Photographer and copyright Leo Carter. From the RA Scholefield Collection.

The Hillson Praga was a very uncomplicated aircraft. F. Hills and Son produced 28 copies of the little Czech monoplane, but when the war started, they retooled to produce sub-assemblies for the Avro Anson and other projects. Photographer and copyright Leo Carter. From the RA Scholefield Collection.

The year 1940 saw thousands upon thousands of defensive fighter sorties being scrambled from airfields throughout the south of England during the Battle of Britain, some of which were too late to engage the enemy at altitude let alone gain a height advantage. It was at this time that Mr. W.R. Chown, the Managing Director of Hillson, considered designing a small, lightweight fighter that would employ an extra wing during takeoff, which could be dumped once the aircraft had climbed to an advantage. The Hillson slip wing fighter concept was proposed as a method of producing a cheap fighter that could take off from minimally prepared fields and roads and climb quickly to altitude. The company had no official support from government, so they financed, designed and built a prototype of a small test aircraft with a detachable wing—in just seven weeks!

The aircraft conceived was a small low-wing airplane with two different sizes of detachable upper wing. Officially it was only known as “Experimental Aeroplane N°133” in the wartime series of prototypes. The nickname given it by Hillson was “Bi-Mono”, for its hoped-for ability to change from a biplane to a monoplane mid-flight. Officials were skeptical and thought that throwing away the wing while aloft would cause problems such as fatal damage to the aircraft or even fatal injury to innocent people on the ground.

The aircraft, wearing RAF livery and official Prototype roundels, was test flown in both the biplane and monoplane configurations at Manchester, but without a jettisoning test of the upper wing. Hillson designers experimented with two different spans for the upper slip wing and settled on the smaller of the two as the one that gave the overall best performance. After evaluation by RAF test pilots, it was moved to the west coast city of Blackpool for a test of the detachable wing. The one and only test flight where the wing was detached at altitude was made on 16 July 1941 and proved that separation could be made without any problems. The upper wing flipped off, lifted by its own aerodynamics and fell to the sea and was lost.

During tests, the pilot reported that the maximum speed in the biplane configuration was actually slower than the stall speed of the monoplane configuration. Naturally, the second the wing was detached, the remaining monoplane aircraft went into an immediate stall and dropped “a few hundred feet”. After the Blackpool tests, the aircraft went to RAF Boscombe Down for further testing by the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment.

The Hillson Bi-Mono slip wing concept aircraft

Over the past month, I have collected several images of this unique and diminutive aircraft from numerous sources on the internet. While some are redundant, I have placed ALL of them together in this article so that there is a repository of all the images found on the web. Perhaps this will intrigue others enough to search for and bring to light other photographs of the Bi-Mono and hopefully images of the test where the wing was jettisoned.

Related Stories

Click on image

A clear shot of the diminutive Hillson Bi-Mono test aircraft looking almost fighter like without its jettisonable upper wing and sitting on the grass at an airfield—likely RAF Boscombe Down. Hills and Son was a subcontractor for its Mancunian neighbour, Avro, for Anson sub-assemblies at the beginning of the war, but had been building, under licence, a light aircraft called the Praga before the war. The light colour on the Bi-Mono’s wheel pants and underside of the wing would have been bright yellow as all prototype and test aircraft were. Flight testing of the little aircraft began at Barton Airfield in Manchester in early 1941 in both configurations—as a monoplane and a biplane. A wing jettisoning trial was still called for, but the event was moved to Squires Gate Airport near Blackpool on the west coast of England. This move was done because the jettisoned wing was a danger to the civilian population if dropped over land. Over the Irish Sea was definitely safer. Flown by test pilot P.H. Richmond and shadowed by a Lockheed Hudson full of observers, the first live separation look place on 16 July 1941. During the process the aircraft dropped a couple of hundred feet. Photo via AviaDejaVu

The Hillson Bi-Mono was a very small aircraft indeed—especially for a military one. It was just over 19 feet long with a wingspan of 20 feet. In this image we can see the asymmetrical vertical air intake common to aircraft which are powered by the de Havilland Gipsy engine (Tiger Moth, Fox Moth, Chipmunk, etc.) The Bi-Mono is sometimes described as a mini-Hurricane in appearance, but looked more like a children’s amusement park ride. Image via rcmf.co.uk

The Bi-Mono’s cockpit and canopy gave an exceptional 360º view for the pilot in the monoplane configuration. Because of the tiny size of the aircraft, the seemingly roomy cockpit was clearly small when a pilot was stuffed inside. In addition to the yellow undersides, the Hillson carried standard military camouflage of the day—Ocean Grey and Dark Green on her top surfaces—plus a large Type A-1 roundel on her sides with a small “P for Prototype” roundel aft of that. Photo via AviaDejaVu

The Hillson Bi-Mono showing her Type B roundels on her upper wing surfaces (just like the big boys!) and the oversized ailerons. This photo seems to have been taken at another time than those above as the propeller is clearly different. Photo via forum.keypublishing.com

The Hillson Bi-Mono in its full Bi-glory, sporting the longer of its two jettison-able top wings. The test flights were made both as a monoplane and as a biplane, with the shorter upper wing being chosen over this considerably longer wing. The shorter upper wing was of the same span as the lower one. In this photo, one could claim this was not a biplane, but correctly a sesquiplane—a biplane having one wing of less than half the area of the other. Image via rcmf.co.uk

A clear view of the size and depth of the large upper wing and the simple inter-plane strut connections. The upper wing would clearly impede entry and exit of the aircraft. The total height of the aircraft was just 7 feet in the biplane configuration and 6’4” as a monoplane. The structural design and quality of construction of the upper wing was required to be of the same standards of airworthiness as the rest of the aircraft. This made it an expensive component to dispose of in flight. Photo via AviaDejaVu

A straight-on photo of the little aircraft shows the larger upper wing, one of two sizes studied in the test phase. Looking at this, it seems quite a risk to consider pressing a button and letting the wing and strut assemblies go flying off while in flight. Given the size of the remaining wing, it was obvious even to the uninitiated, that the aircraft would most certainly drop a great height before gaining control again.

An excellent head-on shot of the Hillson Bi-Mono shows bigger upper wing and the inter-plane struts which were lined up with the wheel pants. Photo via AviaDejaVu

A wonderful shot of the Bi-Mono in flight with her shorter upper wing. No other RAF biplanes wore roundels on the topside of their lower wings or the underside of their upper wings, but because the Bi-Mono would fly without the top wing, it needed roundels. Apparently, the Hillson was “interesting” to fly. Author Tim Mason in “The Secret Years - Flight Testing at Boscombe Down” wrote, “The pilot reported that the maximum level speed as a biplane was less than the stalling speed as a monoplane; in other words, jettisoning the top wing caused an immediate stall. The company pilot had earlier reported a gentle sink of a few hundred feet on jettisoning. The monoplane landing was described as like ‘a high Speed kangaroo.’ ” Photo via aviarmor.net

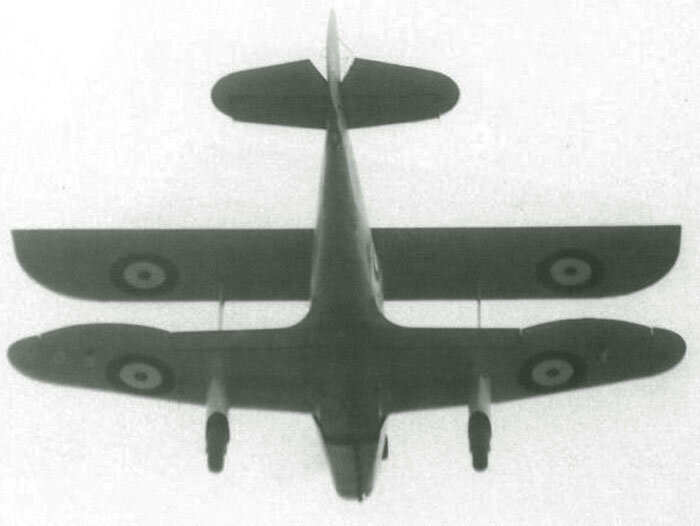

The Bi-Mono with its short upper wing attached in flight. From beneath, we see the enlarged ailerons on the lower wing designed specifically for when the upper wing was in place. It was also later determined that the ailerons of the eventual biplane Hurricane would have to be enlarged to provide suitable control.

The Bi-Mono in flight. Photo via forum.keypublishing.com

The Bi-Mono shot from exactly the same angle as the previous image, but without the upper wing. Note the size of the pilot inside. The original idea behind the Bi-Mono was to develop the concept for a new lightweight fighter aircraft capable of operation from a short field. As far as I can tell, only one successful, ‘slip’ was made—on 16 July 1941, at a height of 4,500 ft oversea off Blackpool. After trials, the concept of a brand-new, lightweight, slip-wing fighter was dropped. Instead, it was decided to adapt a Hurricane by adding a second wing to see if Hurricane operations could benefit from such a scheme. Photo via forum.keypublishing.com

The test pilot takes the little biplane out over the Irish Sea west of Blackpool on the coast. It was over the Irish Sea that the one and only wing dropping was successfully carried out. Note what appear to be guide rails on the elevators and rudder, perhaps to prevent the wing from striking the control surfaces, though they look fairly light for that purpose. Photo via aviarmor.net

An excellent three-view drawing of the Hillson Bi-Mono. Illustration by 2-Ni-Sun

The Hillson FH.40 Slip Wing Hawker Hurricane

Despite the less than spectacular results of flight and jettison tests, there was just enough promise left in the project for the Air Ministry to grant Hillson the use of a somewhat clapped out former Royal Canadian Air Force Hawker Hurricane I to test the concept out further on a full-sized aircraft before committing to further design. The result was the Hillson FH.40, a Hawker Hurricane with a massive and identical second wing propped on slender N-struts high above the fuselage. I was not able to find any report that suggested that the biplane Hurricane ever attempted to jettison its wing, but it seems the project had changed to more of a study of how an extra wing might benefit a Hurricane for ferry flights and getting off the ground with heavier loads than as a possible slip-wing defensive fighter.

The strange aircraft was tested at RAF Sealand during May 1943, and at the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment at RAF Boscombe Down from September 1943. The upper wing was not released in flight before the program was terminated due to poor performance. As with the Hillson Bi-Mono above, I have collected and published here all of the images I was able to scour from the internet.

The Hillson Bi-Mono was designed as a proof of concept aircraft, with plans to create a unique small fighter with the same wing concept. But before going to the effort and cost of designing and building a new aircraft, Hillson obtained Air Ministry permission to fit a slip wing to a Hawker Hurricane I. The Hurricane aircraft used for this experiment was an early Mk I, one of 20 originally transferred to Canada in 1939 and then returned to UK in 1942 (originally it carried RAF serials (L1884) on the fuselage, but when it returned it kept its newer RCAF serial 321 for slip wing trials). First taxi trials and flights were conducted at RAF Sealand (traditionally a training base), 25–28 May 1943. On 15 September 1943, Hurricane 321 was ferried to the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment at RAF Boscombe Down for further trials with the Performance Testing Squadron. Photo via alternathistory.org.ua

The slip wing Hurricane was an impressive if strange sight. Structurally, the slip wing itself, attached relatively lightly as it was, was not designed to handle the aerodynamic stresses and g-forces of combat. The bi-wing concept was experimented with as a device for ferrying aircraft (with the upper wing possibly functioning as a massive flying gas tank) or to allow the aircraft to take off from shorter fields with heavy payloads. Photo via forum.largescaleplanes.com

The slip wing Hurricane was actually designed to enable a Hurricane to lift a greater load or take off from a shorter field, but it was found that later Hurricane variants could achieve the requirements on their own, so the idea was not necessary. Photo via AviaDejaVu

This underside shot of the Hillson Hurricane biplane looks more like two Hurricanes flying in tight formation than the bi-winged prototype. Unlike most biplanes, the Hurricane had struts close to the fuselage and no wire bracing. The design of the wing had to allow for simplicity of jettisoning. The underside of the wings was likely bright yellow as most test aircraft wearing the yellow Prototype P roundel were painted bright yellow on their undersides. Photo via AviaDejaVu

A nice shot of the Hillson Hurricane with its massive second parasol-like wing. One can only imagine what kind of range the upper wing could offer the Hurricane if it had been used as a flying gas tank, but the inter-plane struts do not look robust enough to carry a considerable load. Once that wing was jettisoned, it was just an ordinary Hawker Hurricane again. The additional wing was designed with the same plan form and airfoil sections as a Hurricane’s but had no ailerons. Image via rcmf.co.uk

A clean port side view of the Hillson FH.40 slip wing Hurricane showing her yellow “P” for Prototype roundel, worn on RAF aircraft being tested and evaluated. We can also see her old RCAF serial number—321. This aircraft was a Hawker-built Hurricane I (L1884) which had been shipped overseas to Canada in 1939 and given the serial 321. On 22 May 1939, the aircraft had entered service with the RCAF at Sea Island, British Columbia. A year later, it was in Canada Car and Foundry (Can Car) in Fort William for repairs. Some records indicate that it was used as a pattern aircraft for the builders at Can Car. Following this it was returned to the UK in May of 1940 and assigned to No. 1 Squadron RAF. Later in the war it was used as the Hillson Hurricane test aircraft. Quite a unique history for one Hurricane.

The simple configuration of the slip wing Hillson FH.40 Hurricane in a three view drawing. Image via airwar.ru

The former Royal Canadian Air Force Hawker Hurricane 321 sits in fine sunshine, with the upper slip wing offering cooling shade to the Hurricane’s typically hot cockpit. Of all the Mk I Hurricanes, former RAF L1884/RCAF 321 had a particularly interesting life, including two crossings of the Atlantic in the hold of a cargo ship. Photo via forum.largescaleplanes.com

A great side shot of the slip wing Hurricane in flight sporting its “P for Prototype” roundel. The super clean upper wing had no control surfaces and acted simply as a lifting device. The basic second wing added nearly 700 pounds to the overall weight of the Hurricane—including the “N” struts and release gear. Photo via forum.keypublishing.com

A fantastic head-on shot of the slip wing Hurricane shows us clearly its greater lifting capabilities with so much wing area, more than double that of a standard Hurricane. The frailty of the inter-plane struts is also evident, clearly showing that if the wing could not be jettisoned, the Hurricane was in a peck of trouble if it encountered an enemy fighter.

For a biplane, the Hillson FH.40 Hurricane has a relatively large space between the lower and upper wings. The wing had to be high enough to allow the Hurricane pilot a view forward and to clear the tail when jettisoned. With this large separation, aerodynamic interference between the two wings was likely reduced. Image via airwar.ru