THE VAMPIRES OF LAS VEGAS

In the period immediately after the Second World War, there were two major surpluses created which would ultimately be a breeding ground for either great ideas or bad ideas. Immediately following cessation of hostilities around the planet, war production ground to a halt and the world found itself with hundreds of thousands of surplus aircraft and just as many surplus aviators. Most aircraft would meet the salvage blade and the smelter’s fiery furnace. Most pilots would return to civilian life, the bulk of them never to fly again.

With the plethora of military aircraft languishing in desert lots awaiting a certain fate, some of those disenfranchised aviators and aircraft designers would look to new growing markets for salvation. One of these emerging markets was the new-found requirement for fast and capable business transport aircraft for executives looking to link business interests across the vast distances of the nation. With few purpose-built business aircraft available for executives, medium bombers became the drug of choice for high flying big shots—fast, powerful and, with the right interior appointments, a visual statement of their success and power.

While a few of the big heavy bombers and the odd Catalina were used as corporate aircraft, it was the medium bomber aircraft of the United States Army Air Corps that provided the right balance of speed, cost effectiveness and comfort to fill the immediate gap in the demand for business transport. Until the arrival of the Grumman Gulfstream I and the Lockheed Jetstar, the surplus medium bomber became the business transport’s salvation.

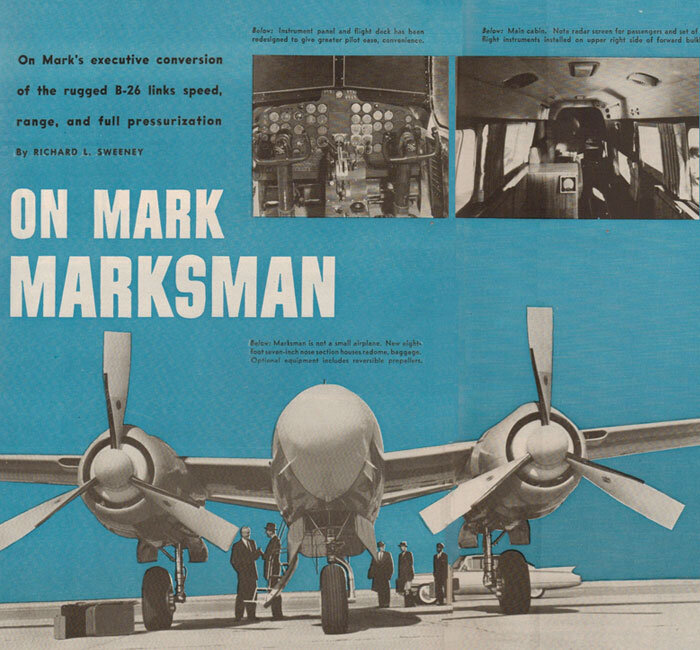

Surplus airframes like the A-26 along with surplus aircraft designers and engineers combined to create new business types and new business aircraft companies. One such company, On Mark Engineering Company, took surplus and low time A-26s and began creating a series of business aircraft including the Executive, the Marketeer and the Marksman. In building this series of business aircraft, On Mark learned that a bomber is not a business aircraft and that modifications were needed in order to fill the emerging needs of executives on the move and seeking comfort at the same time.

In early variants like the Executive, On Mark simply removed military equipment and replaced them with fairings and civil avionics, sealed the bomb bay doors, soundproofed the cabin, and added additional cabin windows. Later models had special wing spars designed to give more interior room, pressurization and equipment from bigger surplus aircraft such as DC-6 brakes and flat glass cockpit windows. It was an elegant mashing together of equipment, but it was not a true business aircraft.

Until the advent of the early business aircraft like the Grumman Gulfstream I in 1958 and the Lockheed Jetstar in 1960 there were few types, if any, that were purpose-designed as business aircraft. After the Second World War, corporate aircraft buyers could buy a surplus Douglas DC-3, get a small piston-engined twin aircraft from Cessna, Beech, or Piper, or a refit surplus bomber. These former bomber conversions had a speed and range advantage over both the DC-3 and smaller piston aircraft, making them the high-end of this new and emerging aircraft sector—the business aircraft. One of the more common executive postwar conversions was the North American B-25 Mitchell—inexpensive to acquire, easy to adapt, and had a reputation as a good handling aircraft (which was why there were so few B-26 executive conversions after the Second World War).

The On Mark Marksman was an American high-speed civil executive aircraft converted from surplus Douglas A-26 Invader airframes by On Mark Engineering. Its antecedents were the On Mark Executive and the On Mark Marketeer. The On Mark Engineering Company was involved in the maintenance and conversion of Douglas A-26 Invaders for both civil and military customers from 1954 to the mid-1970s. The first conversions mainly involved the removal of military equipment and replacement with fairings and civil avionics, sealing of the bomb bay doors, soundproofing, and additional cabin windows. The original “gunner’s hatch” was replaced with a larger retractable entrance door, room for baggage was provided in the nose section. They had improved brake systems and fuel systems and uprated engines with reversible-pitch propellers. Image and words from Wikipedia.

Brochure for the Marksman from the Van Nuys, California builders On Mark Corporation, used a pretty obvious visual trick to make the Marksman aircraft appear to be more powerful and larger than it was. Also, as many advertisements were in those days, it’s racist, as a black chauffeur carries the bag of his charge as they arrive in a mightily finned Cadillac.

Further development continued into the 1960s into what became the On Mark Marksman. The major difference was the addition of full pressurization. Improvements were also made to the cockpit with the incorporation of Douglas DC-6 flat glass windscreens and cockpit side windows. A replacement fuselage roof structure was added from the new windscreens, tapering back to the original tail section. This image of Marksman N827W, the second of eight A-26s converted to the Marksman, was owned by the Wheaton Glass Company of Millville, New Jersey. The photo was shot by Larry Green in June 1961 at a Reading, Pennsylvania air show. Photo: Larry Green

Related Stories

Click on image

Soon, purpose-built executive transports would arrive on the scene and a whole new field of aviation had begun. Some of the Marksman aircraft still exist today, but they are relics of a transitional period and flown more for their warbird lineage than as business aircraft. While all this was happening, there were numerous attempts by military aircraft suppliers to convert their new military jet aircraft to a high-speed business purpose. French manufacturer Morane-Saulnier joined forces with Beech to create the hybrid Paris jet, and even Cessna made an attempt to inflate their T-37 Tweet to accommodate four seats. Both companies learned early that there was no market for a four-seat high-speed business jet without comfort—little better than normal passenger seating. Cessna was out before even building a prototype and Morane-Saulnier built a few but in the end, the market proved to be focused on comfort and luxury. Both were out of the game before the early 60s. Lessons learned. For the world of aviation, and in particular the world of business aviation, to expand and become the ubiquity it is today, a reputation had to be built for reliability, honesty, safety and plausibility.

Then there was Johnny Skyrocket.

Skyrocket was one of the most deluded, persistent, interesting and convincing failures in the world of business aircraft design and sales. It would be Johnny Skyrocket’s lifelong quest/crusade to turn the diminutive and obsolete de Havilland Vampire into a low cost four-, six-, eight- and even 17-seat business jet to compete with the newly emerging purpose-built business transports. He would press, cajole, convince and even get jailed for sucking funds from friends and investors for two separate swings at the business aircraft ball, and fail completely both times. There were two things he never learned over his decades long obsession—low cost was not a priority for the high-end business executive and no one wanted an aircraft converted from a used warbird, with seating like an airliner and speed matched and exceeded by aircraft like the Lockheed Jetstar and Hawker Siddeley HS125.

There is not much information about John E. Morgan, aka Johnny Skyrocket, that I could find on the internet, but he is one of the most interesting, if suspect, characters in postwar aviation. Perseverance and some cyber sleuthing did in fact bring to light some of his history. He was born in New Martinsville, West Virginia around 1925. I could not determine if his flying abilities had been the result of military training, but given his age and his skills, it is likely that he either was a late Second World War pilot or a postwar military aviator.

This entire story was seeded in my mind when I came across a single image of a forlorn-looking business jet aircraft on Airliners.net. It pictured a Frankensteinian aircraft that seemed to have the wings and empennage of a de Havilland Vampire fighter aircraft and the forward fuselage of a Piper Navajo. The aircraft was photographed by Andy Martin, sitting parked and languishing in the Nevada heat on a concrete stand, surrounded by weeds and sand. The sun-bleached Nevada mountains sawtoothed across the horizon in the haze. I was immediately possessed of the notion to find out all I could about this strange and information-thin aircraft. Usually, I can be assured at least a small Wikipedia entry for rare and short-run aircraft, but with the Mystery Jet, I had nothing. That just made me dig more.

In my searching for information about this aircraft, built by a Nevada-registered company called Jet Craft, the name of the chief executive and biggest promoter of the concept came to light—a man by the name of John E. Morgan. Toward the end of my investigation on the web, I too became possessed—to find out more about this truly interesting aviation character and his sometimes suspect, always colourful personal history.

The earliest newspaper reports that I found depicted John Morgan as both a flashy showman and an aviation/air show promoter living on the edge of legitimacy. The earliest record of Johnny Skyrocket was in an advertisement for an air show in the Dover Daily News of 11 October 1958 for a “Thrill-o-Rama Day” at the Magnolia Airport featuring “Johnny Skyrocket and his Golden Vampire Jet”.

The earliest news story I could find about John E. Morgan indicated that he could be counted on to make the odd bad decision. The short story in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette of 22 June 1961 read,

“Wheeling, W.Va. Johnny Skyrocket was acquitted today of a charge of reckless operation of a jet aircraft, the first case of the kind in the state. In directing the not-guilty verdict, Judge C. Lee Spellers of Ohio County Intermediate Court said: ‘He was up there in a jet plane and wanted to get down. He came in and landed the best he could and it was unfortunate that people were on the runway at the time.’ Johnny Skyrocket is the name used in air shows by 35-year-old John Morgan of New Martinsville. He flies a Vampire jet, the only privately owned jet airplane licensed in West Virginia. The charge grew out of an incident at Ohio County Airport last Sept. 22. Coming in from Dubois, PA, he landed while a paint truck was on the runway. Morgan ground-looped trying to avoid a collision, but a wing struck the truck and both the plane and the truck were damaged. No one was hurt.”

As well, the Beaver County, Pennsylvania Times of 1 September 1961 stated that at the National Air Show at the Beaver County Airport,

“A highlight will be the appearance of Johnny Skyrocket, ‘America’s fastest private jet pilot.’ He is a favorite of boys and girls with his 500 m.p.h. Golden Vampire jet. Johnny Skyrocket will appear 10 September at 7 PM in his blue satin space suit, silver helmet and boots. After a fireworks display he will board a 40-foot rocket to demonstrate the procedure of a rocket launching. There will be a countdown and actual blast-off effects.”

This satin-cloaked-hero-of-the-air image was coupled with other news clippings which seemed to shed light on a darker side of the silver-helmeted Johnny Skyrocket—one which showed he was capable of bad decisions and the odd fraud. I found another article in the Delaware County Daily Times of 29 November 1962. The article states,

“Show people are not the only ones who believe that the show must go on. Pittsburgh detectives arrested a West Virginia man Wednesday for failing to put on a musical show after he had allegedly advertised and sold tickets for it. Detectives said John E. Morgan, 37, of New Martinsville, W.Va., had placed thousands of tickets on sale in stores, at $2.50 each, for a show advertised as Musical Aviators. But they said the show was not staged and Morgan had not rented the hotel ballroom where it was supposed to be given. He had also failed to pay a $283 hotel bill, they added. It was not known how many tickets were sold. Morgan was charged with defrauding an innkeeper, passing worthless checks, and advertising falsely.”

Another article described the same fraud in more detail and a somewhat tongue-in-cheek manner:

“Johnny Skyrocket got caught on his pad last night, and his ‘Musical Aviators’ never got off the ground. City detectives greeted him in his Penn-Sheraton Hotel room about 5 PM yesterday.

They said that ‘Johnny’, identified as John E. Morgan, 37, of Box 91, New Martinsville, W.Va., had: A: Scheduled a big rock ’n roll show with his ‘Musical Aviators’ in the Hilton Hotel’s grand ballroom for 7:30 last night. B: Advertised extensively with folders and had placed thousands of $2.50 tickets for sale in downtown stores. C: Written numerous checks. Among the things he didn’t do, detectives said, were: A: Pay a Hilton bill of $283, B: Reserve the Hilton’s ballroom, C: Fulfill the advertising.Morgan was arrested on charges of defrauding an innkeeper, passing worthless checks and advertising falsely. There was no show at the Hilton or anywhere else. Police said also he had no permit to operate in the city, and that he was not located in an office he had given as his address in the Century Bldg. downtown.

A Hilton spokesman said relatively few people were disappointed last night. He said there were several phone calls about the show but only a few ticket holders showed up. Among the ‘disappointed’ was a young Pittsburgh woman, her auburn hair beautifully coiffured, her makeup immaculate. She was to have been part of the show. She preferred to remain anonymous.

Her friends said she and about nine other singers and dancers, in additions to a three-piece musical combo, had rehearsed for about two weeks, both at the Hilton and at the Penn-Sheraton. The last rehearsal was at the Penn-Sheraton last Tuesday night.

‘Johnny’ was last seen in the company of Detectives Joseph Becker and George Marshall, who took him to Central Police Headquarters where he was booked and questioned. Said a Penn-Sheraton spokesman, ‘We got off lucky. He only owed us $13.85.’ ”

The future founder of Jet Craft, John E. Morgan, purchased Royal Canadian Air Force Vampire (17038) seen here (N6876D) and dubbed it the Golden Vampire with Johnny Skyrocket written on its nose. Though there are reports of Johnny Skyrocket appearing in air shows in the Appalachians in the summer of 1958, the RCAF serials registry run by R.R. Walker indicates that Morgan did not take title of this aircraft until December of 1958. He became a flamboyant air show performer and promoter and used his Vampire to entertain huge crowds of jet-crazy Americans. It was while flying this Vampire that Morgan fell in love with the little military jet fighter’s performance. He would forever be convinced that the Vampire was the perfect platform upon which to build a business jet—while others thought he was crazy.

In the hands of Johnny Skyrocket, Royal Canadian Air Force Vampire 17038 was painted in flashy metallic gold and called the Golden Vampire. During her operational life, she was all business as seen here on the 402 Reserve Squadron at RCAF Winnipeg, Manitoba. Vintage News contributor Bill Ewing was at Downsiew with VC920 (Navy Reserve Squadron) when he witnessed ex-400/411 RCAF Vampires fired up and flown out to Flightways in Wisconsin. Bill remembers: “What got me was the takeoff. A full-blast run-up, then release the brakes and get off the ground asap. Then the nose would go as close to straight up as possible. When questioned, one of the pilots hired to fly them out remarked that they had to take off that way . . . the Vampire had no ejection seat!!” Photo via Bill Ewing

In another news clipping from the 2 March 1963 St. Petersburg, Florida Evening Independent, Johnny Skyrocket’s image as a supersonic caped crusader was pumped enthusiastically, when he was billed as “The Lone Ranger of the Air” who performs high-speed maneuvers overhead in a gold painted Vampire jet fighter.

In the 29 May 1964 Beaver County Times, a report was found that showed Johnny was getting desperate and that his reputation was in tatters. It reads,

Jet Plane for Sale Anyone wishing to own a jet-powered airplane will find one for sale at the Beaver County Airport Chippewa Township. A British-made Canadian Vampire single engine jet which was seized and impounded by Sheriff John W. Hineman Jr. on an attachment for debt was sold at a sheriff’s sale on Wednesday, and is now offered for resale by the purchaser, with Joe Rabassi as agent.

The 400-mile-per-hour jet was owned by Johnny (Skyrocket) Morgan who promoted the air show presented at the county airport a few years ago. It was impounded by the sheriff when Morgan landed it at the county airport nearly two years ago. Sheriff Hineman said the claim for which the plane was originally seized was satisfied by Morgan but another claimant entered suit, and it was for that debt that the jet was sold.

The purchaser, who bid $4,650, was Guy Reed, Pittsburgh, a representative of the claimant. Apparently there were no other bidders. Rabassi says the jet is a good airplane, but would need some repairs and reconditioning before flying again. Since being impounded it has been kept in a tie-down area at the airport.

Our flamboyant rocketeer in the satin suit and cape may not have been the finest of aviators either. In a listing of accidents from the National Transportation Safety Board, I found a record of a landing accident to the Golden Vampire which indicated Vampire N6876D suffered “substantial” damage in a landing accident in July of 1965 in Benedum Airport in Bridgeport, West Virginia when the gear collapsed after a hard landing. Benedum Airport is close to Morgan’s hometown of New Martinsville, West Virginia. The listing says that the pilot was 40, had no certificate and attempted operation with known deficiencies in the equipment—in this case an inoperative Airspeed Indicator. It also said that Morgan had 136 hours on the Vampire at that time and a total of 4,000 hours flying time. The strange thing is that, according to the earlier article in the Beaver County Times the year before, it had been sold to a Guy Read of Pittsburgh.

Despite his heroic nom-de-plume and his Evel Knievel image, John E. Morgan’s reputation in the Appalachians was going south and so did he—to Las Vegas and Reno, Nevada, where he surfaces about 5 years later. In a 1970 Sports Illustrated article about showman pilots and swashbuckling aviators, William Johnson wrote this about John E. Morgan, the future charismatic Jet Craft Mystery Jet entrepreneur from New Martinsville, West Virginia,:

“The flashiest guy I ever had, not the best pilot maybe, but the loudest and the dressiest, was Johnny Skyrocket. I won’t tell you his real name because he’s a big success in Las Vegas now, I believe. But this was in the ’50s, and Johnny Skyrocket flew this de Havilland jet. He named it the Golden Vampire. He would wear a cape and a golden flying helmet covered with dazzle dust, and he had a big golden J on the chest of a blue uniform. And he had a mask. He would get into town before a show and go jumping into all the TV studios and the newspaper offices and the hotel lobbies wearing that damned outfit. The suit itself cost him $1,600, he told me. Then he’d fly a show, maybe a few little rolls and stuff in that jet, and when he was done he would drive it inside a tent and put a stepladder up to the cockpit. He charged $1.50 a head to go in and look. People hadn’t seen many jets in those days, and Johnny Skyrocket used to make himself a bundle. I’d give a lot for a Johnny Skyrocket these days.

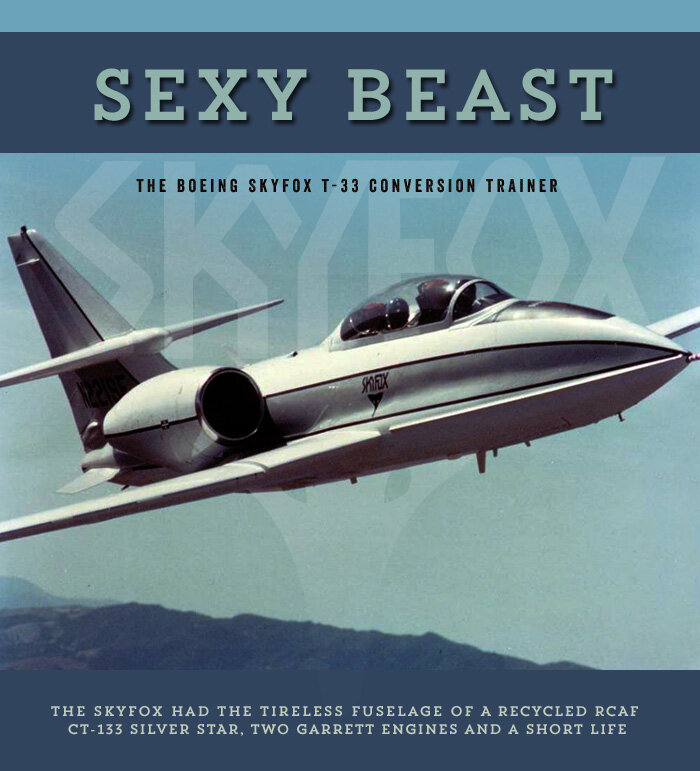

Well, at about the time this story had appeared in Sports Illustrated, Johnny Skyrocket was solidly embroiled in a failed attempt to fund and build a business aircraft based on the de Havilland Vampire fighter aircraft, long-surplus to the requirements of air forces of the British Commonwealth. John Morgan’s experiences flying the little underpowered jet fighter must have convinced him that it would be the perfect platform upon which to build a new enterprise, one that was overshadowed by scamming and illegal activity.

Sometime in the latter part of the 1960s, Morgan had slipped out of his cape and blue satin spaceman suit and donned the dark business suit of an executive, the President of Jet Craft Ltd. of Las Vegas, Nevada. The company had purchased a number of former Royal Australian Air Force Vampire trainers and RCAF single-seaters, which they were to convert to a new design for a 6- and 8-seat business aircraft called Mystery Jet.

Jet Craft worked with stellar British conversion experts Aviation Traders and Marshall’s to do the structural design work. Aviation Traders Limited (ATL) was a war-surplus aircraft and spares trader formed in 1947. In 1949, it began maintaining aircraft used by some of Britain’s contemporary independent airlines on the Berlin Airlift. In the early 1950s, it branched out into aircraft conversions and manufacturing. During that period it also became a subcontractor for other aircraft manufacturers like the dreamers at Jet Craft. They were famous and respected for their Carvair automobile transporters based on the Douglas DC-4. By the end of the decade, it was taken over by the Airwork group.

Aviation Traders worked on the drawings and the structural mock-ups, but when Jet Craft got into legal troubles regarding the Securities and Exchange Commission and unregistered shares, things began to go south. A mock-up of the Mystery Jet languished at Southend airport for a decade, but there is some evidence in magazines that other Mystery Jet mock-ups existed and had been delivered. For a time, there was a slight buzz (more of a hum really) surrounding the contract made between the reputable British company and the soon-to-be disreputable Jet Craft of Las Vegas.

A press release from Jet Craft at the time touted the partnership and seemed to mention all the right names, reference England or Britain 10 times and put a timeline so tight and optimistic that even the most aviation illiterate could tell they were fooling themselves if not the public. The press release reads,

“Jet Craft Ltd. of Las Vegas products under construction in England where new jet trainer will be certified and put into operation sometime in March, 1969.

British designers and builders have joined forces with Jet Craft Ltd. of Las Vegas, Nevada, to put the first 6-place Mystery Jet into operation in March, 1969. The Mystery Jet 2-place Trainer MJ-T1 will make its first flight under civil standard regulations in England sometime in March of this year also.

The total parts available from many concerns exceed enough equipment and flight structures for 189 airplanes. One such concern is Marshall’s of Cambridge, England, who will rebuild a two-place British aircraft whose components such as booms and gears, wings, etc. will go into all four basic Jet Craft designs. This particular 2-place aircraft will be flying in March, 1969, in England, and will make its Las Vegas debut in late March, 1969.

Another outstanding supporter of Jet Craft Ltd. is Rolls-Royce of Coventry, England who have donated to Jet Craft a 522 Viper Jet engine, which produces 3,400 pounds of thrust and will be used in the 6-place being built at the present time by Aviation Traders. This is a 6-place Executive Business Jet.

$1,200,000.00 worth of engineering drawings and specifications were sold to Jet Craft by Hawker-Siddeley Aviation of England. These drawings and specifications are for the basic components that are to be used in all four Jet Craft products. They have further contracted with the company on option basis for components parts.

The Jet Craft 6-place single engine Business Jet being built by Aviation Traders [Freddy Laker’s company], Southend-on-Sea, England is scheduled for a first flight on July 1st, 1969, and will market for less than $350,000.00. Aviation Traders have a long background of successful aircraft and Jet Craft’s Chief Engineer, Roy U. DeCell is quite pleased with the progress made to date.

Jet Craft President John E. Morgan [the former Johnny Skyrocket—Ed.] and staff are presently in London, England, where they await final finishing touches on the jet trainer in order to certify the aircraft for purchase by the United States.”

There are indications that the troubles facing Jet Craft in Nevada had ripple effects in England and that Aviation Traders may not have been paid in full for the work executed. At the beginning of the 1970s, John E. Morgan’s Mystery Jet concept was put on hold, while he served out a nine month prison term for contempt of court, during a trial relating to questionable stock trading.

The First Mystery Jet Promotional Campaign

One of the first generation Mystery Jet concept models from the 1960s’ attempt to make the aircraft viable. Luckily, the Jet Craft company chose bogus N-registrations for their model aircraft that enabled me to identify whether they were from the 1969/early 70s attempt called the Mystery Jet II or the later 1988 failure of the Mystery Jet III. Photo via Jonathan Kirton

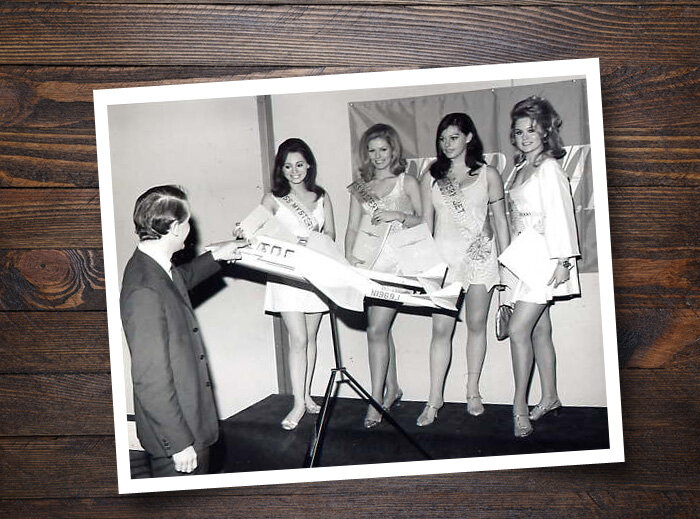

Marketing is king. If you add a little sex into the mix, you can often take people’s hard focus away from a weak idea. Here, a Jet Craft executive and four comely long-legged beauties in Miss Mystery Jet competition sashes make a bigger splash at a media event than the actual aircraft. This promotional event is from the first attempts to finance and build the Mystery Jet in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Photo via Key Publishing’s Aviation History Forum

John E. Morgan, the former Johnny Skyrocket, poses with a model of his fantasy—the Jet Craft Mystery Jet I. When Morgan was an air show promoter and Vampire pilot, he wore a blue satin flight suit and silver helmet and boots. He looks all business in this shot, but under that business suit, he was all showman and show-off. Image via Key Publishing’s Aviation History Forum

In the first iteration of the Vampire-based Mystery Jet in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the well-respected British aircraft structures company Aviation Traders was a partner of the Jet Craft scheme, doing the cabin structural design work and constructing a wooden mock-up of the Mystery Jet cabin with the Goblin engine attached. I think this must be the Aviation Traders’ mock-up. Reader Colin French, remembers this as about 1967 and tells us “I was an apprentice at Aviation Traders at Southend-on-Sea in the UK, and I remember going to see the mock up in the photograph, I believe this was in 1967. At the time there was a programme on our BBC TV, called Tomorrows World. A short documentary film was made about this conversion, showing the mock up. We were told at the time that the project did not get the go ahead due to problems getting the stalling speed low enough for the authorities, but whether this was true or not I do not know.” Image via Key Publishing’s Aviation History Forum

A simple two colour brochure for the Mystery Jet from the late 1960s or early 1970s. John Morgan was handing these out at the Reading Pennsylvania Air Show in 1968. Scan from Jonathan Kirton Collection

The exteriopr of the Mystery Jet in this brochure drawing was pretty fanciful considering it was Morhan's plan to stuff 17 people inside this tiny fuselage. The artis has taken liberties too... thinning out the booms and over-sizing the tails, giving it some extra-racy wing-tip tanks and two engines at the back... apparently all to one of the more diminutive fighters of the first jet age. One thing modern marketers would caution Morgan about to day–NEVER dwell on the negatives such as engine failure, radical compensation, critical moment, engine out and maximum safety. Smart marketing never scares the buyer away from the market sector. Scan from Jonathan Kirton Collection

Seventeen people jammed into this aircraft was a tall order for the little cockpit. A quick scan of the drawings in these pages from the brochure shows seven people jammed into a semi-circular seat at the back. Even sitting in this arrangement for an hour would be a personal space hell. Passenger in the cabin would be able to access pressurized baggage storage compartments in “the forward delta wings”. Though the Vampire had straight, not delta, wings, the misleading language refers to the small angled section where the leading edge meets the wing root. I strongly doubt that the baggage of 17 people could be stored in these tiny spaces. Scan from Jonathan Kirton Collection

Nothing says modern jet travel for the business executive like a Victorian lamp next to your seat at the bar. In some literature, the Mystery Jet interior is listed as 5 feet. while another article specifies it as 4 feet-7 inches. I suspect that a man of my stature (6'-4") would have to crawl into the cabin. Scan from Jonathan Kirton Collection

This spec sheet accompanied the first brochure. At 48 inches, the cabin for the 6 seater was only 2 inches wider than the cockpit of the 2-seat Vampire trainer that Jet Craft was billing as the Mystery Jet MJT-1 Trainer. The 6 foot 2 inch height I believe refers to the aircraft's stature and not the interior dimensions, though this seem short. Scan from Jonathan Kirton Collection

The wooden mock-up was about as far as the company got in the 1969 attempt to build the Vampire-based aircraft. The Mystery Jet MJ1 leaves the Southend Airport in 1983, after languishing there for more than ten years. The Mystery Jet MJ1 was a biz jet conversion of the de Havilland DH115 Vampire, the cockpit section replaced by a stretched cabin allowing up to eight seats to be fitted. The Mystery Jet mock-up was apparently moved from Southend Airport to Bushey, Hertfordshire with its owner Sandy Topen. It was reported to have been burned during a clearance of derelict aircraft on the airfield, however a report said it went to the USA. Image via Key Publishing’s Aviation History Forum

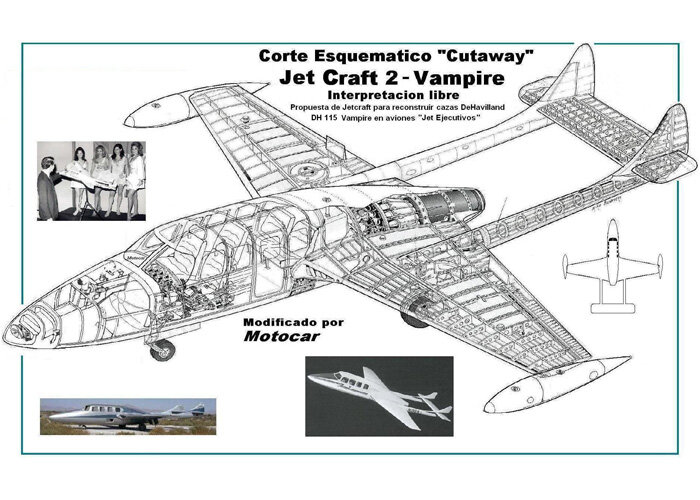

A cutaway drawing of the Mystery Jet, likely created by a third party long after the Jet Craft company folded for the second time. Drawing by Renny Rolando Lopez Guerr, Motocar of Venezuela

According to an article I found on Flight Global’s archive, dated May 1969, this is an image of a mock-up for the 17-seat Mystery Jet MJ-III. 17-seats?????? It’s hard to see how they would have used a Vampire for this concept, though you can see some of the de Havilland Vampire lineage in the configuration. This apparently was to be powered by two General Electric CJ-610-6 engines. Just one look at this toad with wings and potential business aircraft buyers would be turned into non-believers. Image via FlightGlobal

I am no aerodynamicist, but just looking at this layout of the Jet Craft Mystery Jet, I get the feeling that the centre of gravity is far too forward and that the empennage could not handle the pitch, yaw and trim necessary. The engine is at the back of the fuselage to be sure, but it still seems that the cabin is too far ahead. Just sayin’!

The Only Vampire Reputed to have Endured the Conversion

No longer in the service of the Royal Australian Air Force, de Havilland Vampire (RAAF s/n A79-624) here sports very crudely painted N11925 American registrations on her tail booms. This photograph was taken at Oakland, California, on 6 February 1971 where they were assembled and were to be flown to Colorado. She still wears her RAAF roundels and serials and we are surprised she was allowed to leave the country still wearing her proud Aussie markings. This aircraft would be purchased by Morgan’s Jet Craft Ltd in the 1970s and is reputedly the only one to be converted to the Mystery Jet configuration. Photo: Bill Larkins, via adf-gallery.com.au

Another fantastic image by Bill Larkins of former RAAF vampire A79-624 after she was purchased by Jet Craft, sitting outside a sales trailer with Jet Craft flags flapping in a stiff Reno, Nevada breeze. Hard to believe that Jet Craft thought that setting up at a strip mall parking lot was the best marketing venue for a business jet. See next photo for more details. Photo: Bill Larkins

This is a photograph of the former Royal Australian Air Force DH-100 Vampire T.35 (RAAF s/n A79-624), now in the gold, orange and brown paint of N11925. This aircraft was destined to be converted to the 6-seat Mystery Jet and even wears the title “Mystery Jet” on her nose. She is photographed here on Astroturf carpeting outside a sales trailer in a shopping mall in Reno, Nevada in September of 1973. It was one of three ex-RAAF Vampires brought in by boat, given US registrations and assembled at Oakland to be flown to Colorado. It seems from certain posts and items on the internet that N11925 was the only aircraft to be converted to the Mystery Jet business aircraft configuration. Photo: Paul Rued

The colour flyer that John Morgan and Jet Craft handed out before and during the Mystery Jet I's appearance at the Parklane Shopping Center in Reno in 1973. In this flyer, it is clear that Jet Craft was selling the brightly painted Vampire T.35 trainer as the Mystery Jet Two Seat Trainer as if it had been custom designed as a Mystery Jet pilot training aircraft. The idea was to sell potential customers a used military jet for $95,000, train them and then let the owners trade them in for credit on a Mystery Jet II business aircraft. Very slick when you consider they must have purchased the RAAF trainers for considerably less than that. Note that the hourly operating cost for the Mystery Jet was pegged at $150. Operating a Tiger Moth today takes more than that. Flyer scan from Jonathan Kirton Collection

Everything about the Mystery Jet was suspect... including the bad graphics from the outside of the flyer. For a company trying to appeal to the business executive, they were using graphic design more suitable for selling children's wagons. Flyer scan from Jonathan Kirton Collection

Another good photograph of N11925, the former Royal Australian Air Force Vampire T.35 trainer sitting somewhere that looks a lot like Nevada. When I found this image on the web, it did not have a credited photographer, so if you know who took this photo 40 years ago, let me know. The paint scheme on the nose and wing tanks of this aircraft is very typical for civilian registered Vampires that carried a civilian paint scheme, leading me to believe that they were batch painted in various colour combinations when they entered the country, possibly in Colorado.

John “Johnny Skyrocket” Morgan sits in former RAAF Vampire T.35 Trainer (N11925) which he was selling as the Mystery Jet MJT-1 Trainer. The aircraft does look in pretty fair condition. Scan from Jonathan Kirton Collection

A close up of Morgan in the cockpit. I am not certain, but is that plaid upholstery behind his head rest? Scan from Jonathan Kirton Collection

27 lawsuits? Howard Hughes? Conspiracy? $50 Million counter suits? No engines included in the price? Read the above article and you can see that Morgan was indeed obsessed. Scan from Jonathan Kirton Collection

If at first you don’t succeed, try again 20 years later

A colour advertisement in Aviation Week and Space Technology of 29 July, 1985. This is Morgan's last kick at the Vampire business jet can. He has even changed the name to the Whisper Jet. Both names seem somehow appropriate. As the Mystery Jet, aerospace writers and investors thought it was a Mystery why Morgan thought third would work, and by the time it became the Whisper Jet, everyone was whispering behind his back, warning investors to not touch this project with a barge pole. Scan from Jonathan Kirton Collection

Another article by John Medearis in the Los Angeles Times from 23 October 1990 explained Morgan’s second Jet Craft Mystery Jet attempt better than I could ever hope to. Apologies to Mr. Medearis for using it in its complete form.

“John E. Morgan’s vision of a new business jet has put him in peril twice. Once, while piloting one of the fighter planes his dream jet is based on, the aircraft’s engines flamed out high over Texas and he had to glide the plane to the ground with no power.

A second flameout occurred about 20 years ago, after the Securities and Exchange Commission objected to the way Morgan was raising money for his project of converting a World War II-vintage British ‘Vampire’ jet into a six-seat business jet. Morgan still maintains that he did nothing wrong, but there was no soft landing that time: Morgan served about nine months in federal prison for contempt of court.

Now, Morgan’s Las Vegas-based Jet Craft U.S.A., Inc. is trying to raise $25 million from a proposed public stock offering to build a modern version of the Vampire and sell it to businesses. But even if he raises the money—a big if given today’s sagging stock market, which has been unfriendly to start-up companies—winning Federal Aviation Administration approval for such a plane will be tough, and finding buyers for Morgan’s unusual plane might not be a breeze either given the crowd of established jet makers.

Morgan plans to use a Van Nuys company—Aircraft Technical Service—to redesign the old Vampire into a new plane, called the Jet Craft Mark I, and get approval to sell the plane from the FA

‘It’s a tremendous business jet priced below $1 million,’ Morgan boasts.

According to Jet Craft’s stock registration statement—filed with the SEC in August—the company hopes to sell 5 million shares of stock for $5 each. Jet Craft hopes to use about $6 million to develop the Mark I—and another $4 million to develop the Mark II, a turboprop plane similar to the Mark I. Both planes would be small, six-seat passenger planes. Jet Craft would spend about $6 million to build manufacturing facilities, while another $1.3 million would go toward salaries and other company overhead. Finally, Jet Craft would put aside $6.5 million to cover potential cost overruns and to actually begin producing the planes.

But whether his idea ever flies could well depend on selling his vision to the stock market. Morgan, however, has already had to put off the stock offering until early next year. He contends that if he can’t raise the $25 million on the stock market, he can raise it from five private investors in England and Germany, whom he declined to name.

Morgan’s plans are ambitious, to say the least. First, Jet Craft, which has never sold a plane, is supposed to finish developing its jet in two years or less. But five to six years is the usual amount of time for the process, said Mike Potts, a spokesman for Beech Aircraft Corp., an established business jet maker.

Getting government approval of a new plane is a notoriously difficult business. Avtek, a Camarillo company that is seeking approval for a business plane made of plastic composites, has been developing its aircraft since 1980, spending $32 million to date, and will probably need to spend a total of $62 million before it’s over, said Robert Adickes, president of the company. From its founding, Avtek has had to scramble for investors and a place to locate its planned manufacturing plant.

Floyd Snow, who runs Aircraft Technical and is vice-president of Jet Craft, counters that it will take less time to get approval for the Jet Craft Mark I because it’s based on an established plane that was flown for 20 years.

Another big claim is that Jet Craft can sell the Mark I for only $895,000. That would make it very competitive even with used business jets selling for a few million dollars. But that $895,000 price would not include the engine, which buyers would have to lease. Beech is testing the waters with a similar engine-leasing plan, but Potts said it’s too soon to know whether jet buyers like the idea.

And there are other potential problems leading Jet Craft to warn—in its registration statement—that purchasing the stock ‘involves a high degree of risk.’ For instance, the company has no income and has no orders for the planes.

Plus, its would-be competitors are much bigger companies with years of experience. One example is Beech, a subsidiary of Raytheon Corp., which recently introduced the eight- to 10-seat Starship business plane. Cessna, which makes the popular eight-seat Citation II, is owned by General Dynamics. Even struggling Learjet is owned by Bombardier Corp. of Canada.

Morgan said he bought the plans to the Vampire in late 1968 and began preparing to manufacture a business version on his own. But in 1969, a federal grand jury issued a 14-count indictment against Morgan and three associates, charging that they had sold unregistered stock to investors in Morgan’s first jet company, Jet Craft Ltd.

Those charges were dropped in 1971, when Morgan pleaded guilty to contempt of court. Morgan said the contempt charges stemmed from government claims that he had violated a 1968 agreement with the SEC under which he had agreed not to sell securities. But Morgan said that he hadn’t violated the order—he had merely sent out a newsletter to existing shareholders asking them to chip in more money for the financially strapped company. The judge, however, sentenced Morgan to the nine-month prison term.”

My search for information regarding this aircraft and the fates of the RAAF and RCAF aircraft that were to serve as its hosts ends here. I have no doubt there is more out there if I just put in the right search words, but it’s time to move on to another story. Perhaps, like many of the stories I write, it will serve as a magnet to draw out the other photos and memories of Johnny Skyrocket, John E. Morgan, Jet Craft and the idea no one seemed to want—the Mystery Jet.

One thing for sure, John E. Morgan, despite his foibles and his failures, was a fascinating character from the annals of aviation history. A promoter, daredevil pilot, showman and dreamer, he may have cashed some bad cheques in his day, and run from the law, but he was made from the same stock as many of the more successful aircraft manufacturing executives, just one with a fatal obsession for a quirky-looking and inexpensive British-designed fighter long past its useful life as anything but an air show act. If it were not for the Johnny Skyrockets, the world of aviation would be far less interesting.

Eddie Coates, a well-known and extremely prolific aviation photographer and historian, lived in Las Vegas for a short while. As luck would have it for this author, he lived right next door to a Jet Craft executive. Here’s what Eddie had to say about that fellow and his Mystery Jet parked outside, “A company in Las Vegas (where I resided in the late 1980s) had a scheme to buy up surplus Vampires and convert them into executive jets (in the mode of the MS.760 shall we say [the Morane-Saulnier Paris jet... more on that later—Ed], although even that sleek bird was outdated by that time). Anyway, the owner of this bizarre enterprise lived close to me on the approach road to Horizon Airport, a GA airport south of ’Vegas. On a hard pad next to his driveway was a mock-up (see following photo). This old codger (typical Western gruff old sod) was gracious enough to invite me into his house where he had several table models of converted Vampires in a similar vein. The entrepreneurial old bloke (don’t you wonder, sometimes, how folks like this, with many irons-in-the-fire, make a living?) was also ‘into’ the maglev train idea to provide rapid transport from L.A. to Las Vegas. If you’ve ever travelled on Interstate 15 on a Friday evening you’d know what an excellent idea this is. I did indicate to him that some difficulties might be encountered in the way of land acquisition, particularly as the thing wound its way from San Bernardino to Disneyland, the proposed terminus. He was dead certain it could be done. Interestingly, the idea is not completely dead and is still being talked about, but I doubt I’ll live long enough to ever ride this 300 mph pipe dream. And if it is done, I am uncertain what ‘piece of the action’ my enthusiastic old friend would enjoy!” Photo: Eddie Coates, Aviation Photographer and Historian

There is very little evidence of the existence of the odd-looking, but appropriately-named Mystery Jet on the web today. Here is a shot of what some claim is former Royal Australian Air Force Vampire T-35 (likely A79-624, later N11925) languishing in the hot sun at Las Vegas in the mid-1990s. The RAAF began phasing out the Vampire Trainer in mid-1969, as their replacement (Aermacchi MB.326H) was phased in. This aircraft A79-624 was sold to America as N11925 in August 1970 along with a number of others, and then ended up in the hands of Morgan’s Jet Craft Ltd. Photo: Bob Kennedy

When Eddie Coates lived next door to John E. Morgan, he was somewhat of a grumpy fellow, but still dreaming big about the potential for the Mystery Jet and other outlandish projects such as the aforementioned maglev rail line. Still parked on a concrete hard stand outside his house near the Sky Harbor Airport was this Mystery Jet. Eddie was not sure whether this was a concept full-scale model or the nearly completed conversion from RAAF A79-624. This aircraft and the one in the previous photo appear to be the same ship, but it seems that Morgan has had it painted and the rudders enlarged. Or perhaps it is a second mock-up or conversion. I found reports on the internet of this aircraft being sighted at the Sky Harbor Airport in Las Vegas as late as 1997, but dismantled and on a trailer. Photo: Eddie Coates, Aviation Photographer and Historian

One Vampire that got away

A wonderful, if sombre, shot of the former RCAF Vampire 17072, registered by Wisconsin’s Fliteways as N6878D after they purchased 30 surplus Vampires from Canada. Virtually all the surviving RCAF Vampires come from this stock and all their registrations begin with N68___. One of the Vampires purchased by Morgan and Jet Craft in their first go-round was this very Royal Canadian Air Force Vampire Mk III, s/n 17072. Morgan had owned it along with N6876D and had it pained metallic gold as part of his Johnny Skyrocket routine. It was a single-seat Vampire, and not as wide as the two-seat side-by-side trainers which were much better suited for conversion to the 6-seat Mystery Jet. Perhaps it was acquired for spares. Its RCAF career included stints with 410 Squadron at St. Hubert (1948–51), including flying with 410’s famous Blue Devils display team. In the mid-1950s, it operated with the reserve at RCAF Downsview, Toronto (400 and 411 squadrons). It was purchased from surplus by Wisconsin’s Fliteways and registered as N6878D. It was owned by the famous stunt pilots and aviation cinematographers Frank Tallman and Paul Mantz (TallMantz), from whom Morgan would eventually purchase it. Photo via aerovintage.com

N6878D (former RCAF 17072) during its time with Tallmantz at Orange County airport. The date that this photo was taken is probably early to mid-60s. In the early 1970s, Morgan’s Jet Craft Ltd. purchased N6878D for conversion to a Mystery Jet, but he had owned this aircraft at the same time as N6976D. Likely, the gold paint was a hold over from the Johnny Skyrocket’s act. Photo: J.D. Davis, aerovintage.com

Another closeup of the Tallmantz Vampire N6878D in what is believed to be movie markings, though the movie is unknown. The gold paint seems to have been applied to everything, inside or out. This airframe and several other Vampires were purchased by Paul Mantz in the 1950s, and this example remained in his collection until purchased by Jet Craft. Photographed at Orange County in July of 1963. Photo: J.D. Davis

The ex-RCAF Vampire 17072/N6878D made the rounds of various owners for a number of years, including famed Hollywood stuntmen Frank Tallman and Paul Mantz. In 1970, Morgan bought it from its final owner for his failed Jet Craft Mystery Jet project. When Morgan went bust and was jailed for obstruction of justice, it made its way through many owners, including John Travolta. It was purchased from Travolta by Wings of Flight Inc. on behalf of the Canadian Air Land Sea Museum located at the Markham Airport. It is seen here in Hamilton in 2005. The aircraft was severely damaged in an engine failure due to oil starvation and a wheels up landing shortly after departing Rochester, NY in 2009. Photo: Andy Vanderheyden

Readers remember Johnny Skyrocket

After publishing this article, some of our readers dug into their filing cabinets and memories and shared them with us. Jonathan Kirton, a Canadian aircraft engineer, historian and writer had this to say of his two meetings with John E. Morgan:

“I first came across Mr. Morgan at the Reading, Penn., Air Show in I think 1968, when he had a booth with the large model which you have illustrated. As Timmins Aviation, we had taken one of our early de Havilland DH-125 completions to Reading, where I remember we won an award for it, for which I still have the Reading certificate.

A good many years later, in about 1978 when I was working for Innotech Aviation at Dorval, Morgan came to visit us. I was then interior design manager, and as it happened all our senior management and sales people were out of town, so he was directed to me.

He said that he was on his way back to the US from the Middle East, and that he was looking for a completion shop that would be prepared to take on the conversion of a used Boeing 707 for a Middle East customer.

At that time Timmins Aviation and its successors, Atlantic Aviation of Canada, and eventually Innotech Aviation, had had some experience with the conversion and completion of corporate and custom interiors into large aircraft, having completed the two RCAF CC-106s; four Icelandic Airways Canadair CL-44D6 Swingtails; two ex-TCA Viscount 724s, including converting them to 744s for FAA acceptance, as well as being the Grumman dealer for Canada, so having completed a number of Gulfstream I & II aircraft, and subsequently being Canadian distributor for the de Havilland / Hawker-Siddeley / BAC-125 Series, of which we ended up completing some 125 examples.

John Morgan was staying at the Chateau Champlain in Montréal for one night and insisted that I join him at the hotel for dinner that evening (for which he paid!) to further discuss his 707 project. I was well aware of his involvement with Vampires, and we also discussed them extensively. I still have his business card, and a brochure and one or two photos of his Vampire III, which he gave to me at that time. I still have a Vampire file, and have an article about Morgan and his project with Aviation Traders, published, I think, in Aviation Week and Space Technology. Needless to say our management quickly discovered something of Morgan’s background, and nothing came of our potential involvement.”

Johnny Skyrocket Morgan's gold foil stramped business card, handed to Jonathan Kirton in 1985. Scan from Jonathan Kirton Collection

Others tried, none truly succeeded

Paris jet F-WLKL, the Morane-Saulnier demonstrator aircraft shows the clean lines and relatively capacious cabin for up to six people. I guess Morgan had a reasonable idea. He just picked an aircraft that was not robust enough. Turning a military jet aircraft into a super fast business aircraft was not just the purview of the nutty, deluded and somewhat larcenous John E. Morgan. The Morane-Saulnier MS.760 Paris was a French four- (or even six-) seat jet trainer and liaison aircraft built by Morane-Saulnier. Based on the earlier side-by-side seating two-seat trainer, the MS.755 Fleuret, but adding an additional row of two seats, the Paris was used by the French military between 1959 and 1997. In 1955, a short-lived venture with Beech Aircraft to market the Paris as an Executive Business Jet in the US market was soon eclipsed by Learjet’s Model 23. Sadly, Morgan could not see the obvious challenge from Lear and Gulfstream and pressed forward with his Mystery Jet... failing twice.

The Beechcraft/Morane-Saulnier Paris jet attempted to appeal to the executive with a fly-it yourself spirit, with advertising graphics that led buyers to believe that the ease and comfort was automobile like, when in fact, thousands of hours of flying experience was required to master the military-like aircraft. Decades after this Popular Science-style image was used, John Morgan would still be hoping the idea would catch fire. It never did, though there are numerous Paris jets still flying today. Image via Retrothing.com

Even the American aerospace giant Cessna got into the business jet conversion business briefly with their Cessna 407—a twin-engine Cessna T-37 Tweet puffed up to carry 4 people. “Cessna set aside limited engineering and marketing resources to analyze the profitability of developing a civilian version of the T-37, based on the aircraft’s power plant and airframe systems. Designated the Cessna Model 407, only a wooden fuselage mock-up of the proposed aircraft was ever produced. As Beech had encountered with the Morane-Saulnier MS.760, insufficient customer interest hindered its prospects.” From The Cessna Citations, by Donald J. Porter. Though Cessna had determined, by 1959, that this type of aircraft had no market, Morgan would press onward for decades... and get no further than Cessna. Photo: Cessna

The concept of the twin-boom central-podded light business jet would eventually come to fruition with the Adam A700, but the concept still proved difficult to sell and the company also went bankrupt in 2008. The Adam A700 AdamJet was a proposed six-seat civil utility aircraft developed by Adam Aircraft Industries starting in 2003. The aircraft was developed in parallel with the generally similar Adam A500 (push/pull twin), although while that aircraft is piston-engined, the A700 is powered by two Williams FJ33 turbofans. The two models have about 80% commonality. The prototype A700 first flew on 28 July 2003. Two conforming prototypes were built. The big swollen belly in this Ben Wang photo taken at San Jose, California, is the external centreline fuel tank. Photo: Ben Wang

The idea of a military fighter aircraft as the basis of a high-speed business transport is one that will rarely become successful, but which will never really die. Even the Russians, with their new-found capitalistic ways and a desire to spend money in the most flamboyant manner, looked to the Sukhoi Su-34 Fullback as a basis for a high-speed, even supersonic, business aircraft. Hard to believe. Photo via Wikipedia

A computer-generated illustration of what the Sukhoi-34-based business jet, called the Fanstream would look like. In this design, there are four engines, and a much enlarged size. What’s truly interesting is that there is a refuelling probe on the starboard side... just where the hell would our uber-rich, environmentally insensitive Russian oligarch get fuel at 40,000 feet? Possibly this would spin off a complete civilian air-to-air refuelling business. Dream big or go home. In this case, they went home, as this project failed completely.

The Sukhoi-based Fanstream business aircraft is depicted climbing out of an airfield, having consumed about as much gas as a Challenger 605 would in a single transatlantic flight. Thank God this concept died like all the rest.

![Eddie Coates, a well-known and extremely prolific aviation photographer and historian, lived in Las Vegas for a short while. As luck would have it for this author, he lived right next door to a Jet Craft executive. Here’s what Eddie had to say about that fellow and his Mystery Jet parked outside, “A company in Las Vegas (where I resided in the late 1980s) had a scheme to buy up surplus Vampires and convert them into executive jets (in the mode of the MS.760 shall we say [the Morane-Saulnier Paris jet... more on that later—Ed], although even that sleek bird was outdated by that time). Anyway, the owner of this bizarre enterprise lived close to me on the approach road to Horizon Airport, a GA airport south of ’Vegas. On a hard pad next to his driveway was a mock-up (see following photo). This old codger (typical Western gruff old sod) was gracious enough to invite me into his house where he had several table models of converted Vampires in a similar vein. The entrepreneurial old bloke (don’t you wonder, sometimes, how folks like this, with many irons-in-the-fire, make a living?) was also ‘into’ the maglev train idea to provide rapid transport from L.A. to Las Vegas. If you’ve ever travelled on Interstate 15 on a Friday evening you’d know what an excellent idea this is. I did indicate to him that some difficulties might be encountered in the way of land acquisition, particularly as the thing wound its way from San Bernardino to Disneyland, the proposed terminus. He was dead certain it could be done. Interestingly, the idea is not completely dead and is still being talked about, but I doubt I’ll live long enough to ever ride this 300 mph pipe dream. And if it is done, I am uncertain what ‘piece of the action’ my enthusiastic old friend would enjoy!” Photo: Eddie Coates, Aviation Photographer and Historian](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1630247754671-G856BCAW1MG7O8OQCL1W/56CA912D-C400-4503-BD35-CA2FB48348A5.jpeg)