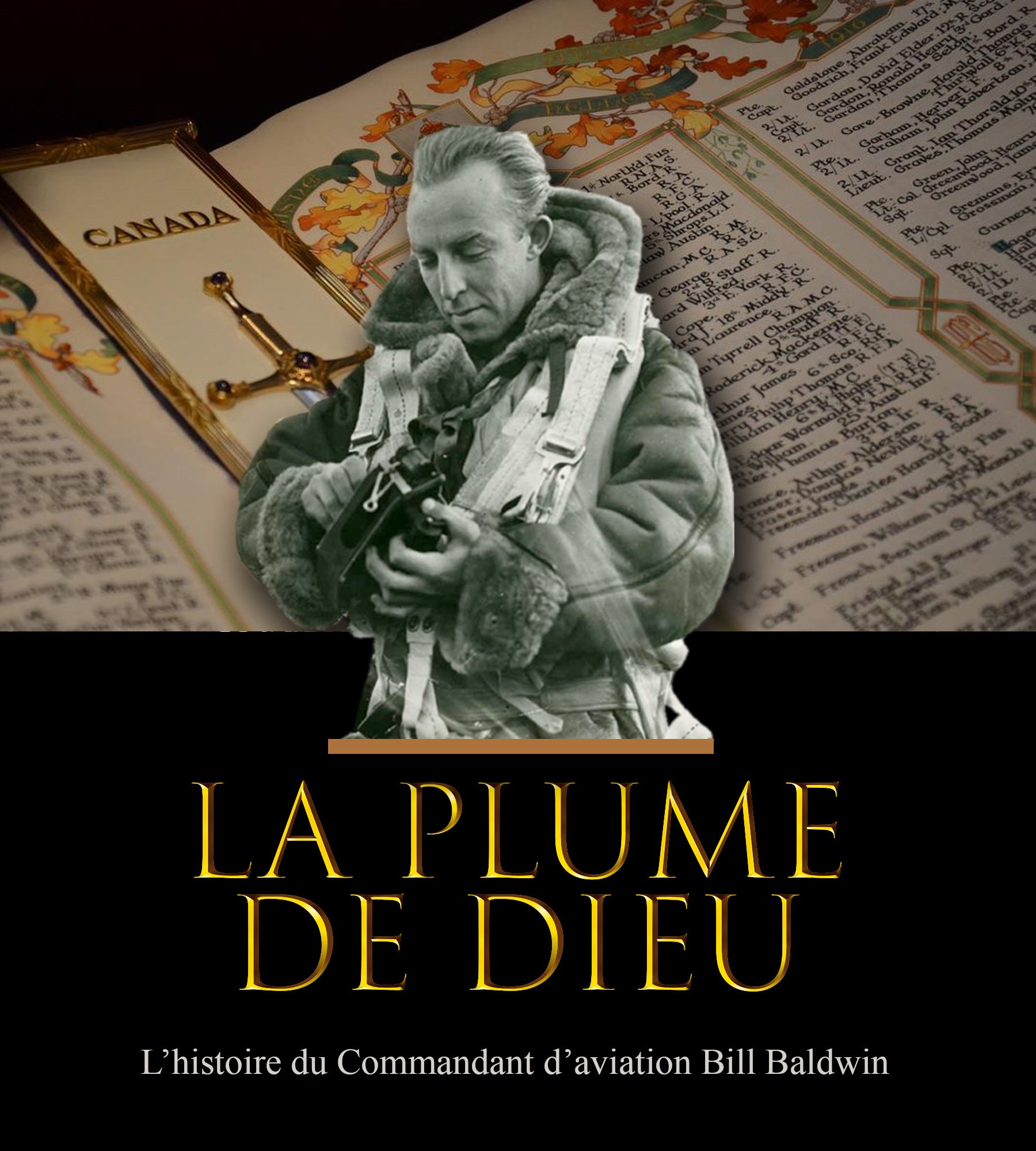

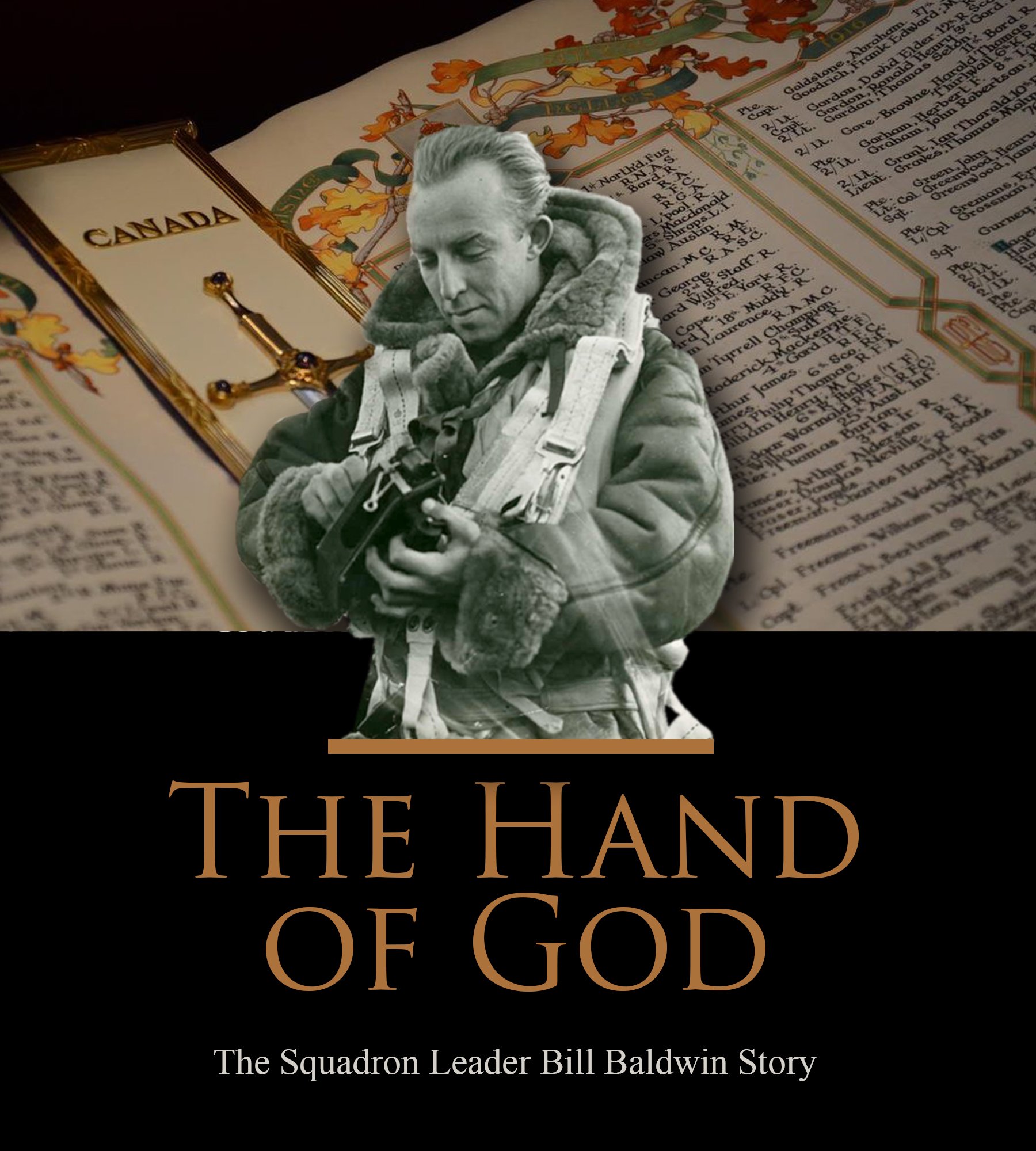

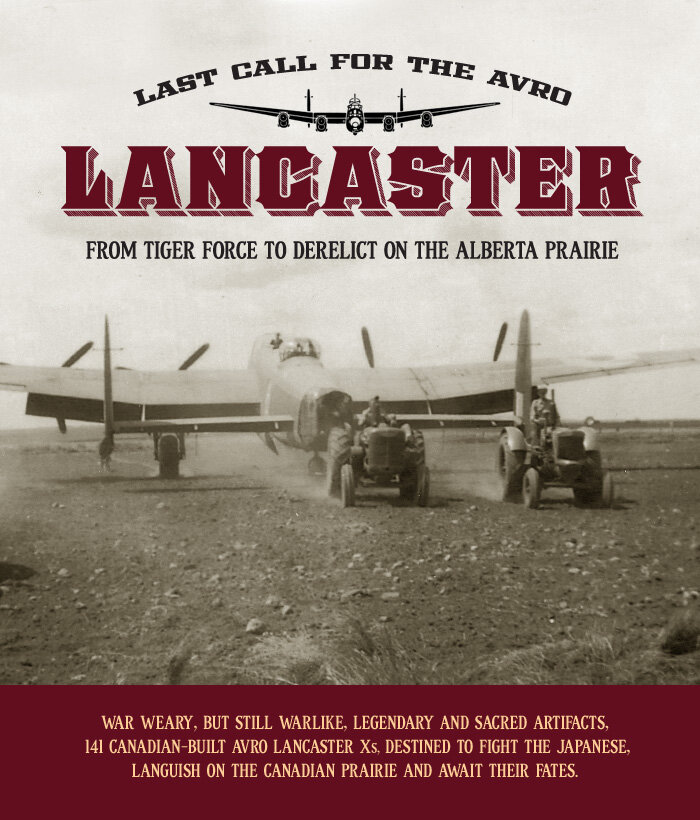

RESURRECTION

In the dark of the night on 2 August 1943, Royal Air Force pilot, Flight Sergeant John Alwyn “Pee Wee” Phillips, DFM, turned to his Flight Engineer, Royal Canadian Air Force Sergeant Herbert C. McLean, nodding that he was ready. McLean, in his folding jump seat, reached to the four big levers between them and pushed the throttles of Handley Page Halifax LQ-B, “B for Beer”, to full takeoff power. The four powerful Rolls-Royce Merlin engines of “their” Halifax responded immediately and she surged forward and gathered speed. In seconds, the tail came up and Pee Wee, who was short in stature and sitting on a custom-made seat cushion, could now see the runway over the instrument panel. McLean and Pee Wee looked down the dark stretch of tarmac, just catching a ghostly glimpse of another 405 Squadron “Halibag” lifting off into the black of the night. Moments later, with his heavy Halifax bomber hurtling down the runway at the very edge of control, Phillips pulled back smoothly on the yoke and the black machine of retribution jettisoned the sweet earth of RAF Gransden Lodge.

As the Halifax lifted into a deadly sky, McLean braked the spinning tires and selected gear up. The massive wheels and tires in their cast magnesium carriages began their laborious hydraulically-assisted travel into the wheel wells within the engine nacelles. Across the field in the control tower, airmen could just make out their departure and into the 405 Squadron operational record book, the adjutant marked the time—2308 hrs.

Climbing into the night, Phillips and McLean worked their way through their tasks—McLean adjusting rpm and boost, retracting flaps, engaging undercarriage up-locks. McLean was a Canadian, hailing from the tiny farming town of Star City, Saskatchewan—in fact he had been the “sheriff” of Star City before joining the RCAF. Though Pee Wee was from Swansea, Wales, 405 was a Canadian unit and most of the lads on his crew were Canucks. Ahead of them, and below their feet, in an extremely claustrophobic and dark space, sat Wireless Operator Sergeant Ron Andrews of London, England. Ahead of Andrews on the starboard side facing the port fuselage wall was their navigator, Sergeant Graham Mainprize, also from Saskatchewan, in his own compartment dimly lit by a gooseneck lamp. Forward still, in the glazed nose of the Halifax, sat their Bomb Aimer, Sergeant Vernon Alfred Knight from Wales.

McLean would spend much of the flight in his own space behind a wall aft of Pee Wee Phillips. Behind him and aft of the wing spar where the crew rest benches were, was Mid-Upper Gunner Wilfred Herbert “Joe” King, another Canadian boy, from Gravenhurst, Ontario, with the most commanding view in all Bomber Command. Far behind them, in the loneliest and, some say, the most dangerous position in a night bomber, was Rear Gunner Sergeant Lloyd D. Kohnke, from Dunblade, Saskatchewan. They were a tight crew, most having been together since they met at 22 Operational Training Unit, at RAF Wellesbourne, Warwickshire flying battered, war-worn Wellingtons. Only Mainprize was relatively new. He came to the crew after they lost their first navigator, Huey Huston (from Vancouver) when he was “borrowed” by the Group commander for a single combat sortie and was shot down. As they climbed out that night, Huston, who had evaded capture, was still on the run in France making his way to Spain and back to his crew.

Into that dark and fateful night, Pee Wee Phillips held a steady hand on the yoke, and more than 50,000 pounds of aluminum and steel, high octane fuel and explosives and seven young hearts clawed resolutely to altitude. Destination tonight—Hamburg. It would be the “Night of the Great Storm”.

The only known photograph of Halifax LQ-B, taken from a period newsreel as she takes off at dusk for another night mission. Blurred but powerfully evocative. Photo via Jay Pinto

The Phillips Crew poses casually with a newly-delivered Halifax LQ-B (HR871) which would become “their” kite for many of their ops before losing her over Sweden. Left to right: Flight Sergeant John Alwyn “Pee Wee” Phillips, DFM, DFC, RAFVR, Pilot; Sergeant Wilfred H. “Joe” King, RCAF, Mid-Upper Gunner; Sergeant Vernon A. Knight, RAFVR, Bomb Aimer; Sergeant R.A. “Ron” Andrews, RAFVR, Wireless Operator; Sergeant Herbert C. McLean, RCAF, Flight Engineer; Sergeant Lloyd D. Kohnke, RCAF, Rear Gunner; and (squatting) Flight Sergeant Graham William Mainprize, RCAF, Navigator. Photo via John Alwyn Phillips, DFM, DFC

Events leading up to the raid on Hamburg, 2–3 August 1943

John Phillips, a clear spoken and thoughtful young man of 20 years, was born in a small village near Swansea, Wales in 1922. After the “Phony War” when the reality of the conflict finally visited Swansea, he volunteered with the First Aid Party (FAP) in the opening months of 1940 as the Luftwaffe began its bombing raids on that Welsh City.

Working by day in the gas company’s offices and at night as an ambulance driver with the FAP, John saw first-hand the tragic results of the bombing. One lunch break at the gas company, John decided to volunteer for the RAF along with some others from his office. He was just eighteen years old. He qualified for pilot training and subsequently was sent to Canada aboard the French liner Louis Pasteur—a grim and miserable crossing through U-boat infested waters. Once in Canada, he was told that his pilot training would be carried out in the United States under the Arnold Plan*. He travelled by train from Moncton, New Brunswick to Montgomery, Alabama, where, in time, he qualified as a pilot under the American system, with silver US Army Air Corps wings. He crossed back to England in July of 1942 aboard Dominion Monarch.

Now, a year later, here he was, a Flight Sergeant pilot, in command of one of 8 Pathfinder Group’s Handley Page Halifaxes on a mass night raid to the industrial city of Hamburg. The lives of his six crew members and friends depended on the decisions he would make this night… and every night.

Pee Wee Phillips was not afraid of this responsibility, he embraced it. He’d had some “dicey do’s” in the past that led him to put a lot of trust in his crew and his aircraft. Following a nighttime practice flight at No. 22 OTU, he was unable to get the undercarriage of his Vickers Wellington down and was forced to make a wheels up landing on the infield grass. The landing went as planned, bending only the propeller tips. Later, coming in for a landing in a Handley Page Halifax at RAF Topcliffe, Yorkshire in January 1943 after a practice bombing run while with 1659 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU), he was met with a severe crosswind before the field could change to another active runway. Landing with a pronounced crab as he flared, the wind caught the wing and “over we went and I went through the windscreen”. His entire crew was uninjured, but he suffered a concussion and lost some teeth. While the rest of his crew were given leave until he recovered, he had to spend the time in the hospital.

1659 HCU at RAF Topcliffe fed new crews to the Canadian 6 Group squadrons based there and at aerodromes throughout Yorkshire. Phillips and his crew were assigned in February to 405 Squadron, the senior bomber squadron of the RCAF, having been the first to form in England in 1941 and was the first RCAF squadron to bomb the Germans. After joining the squadron, Pee Wee, as the future aircraft commander, was required to fly his first combat operation as second pilot (called a Second Dickey Flight) with an experienced crew, while his own crew rested. Pee Wee’s first taste of combat was a lengthy and dangerous mission to Berlin itself. At the end of February, the squadron began flying anti-submarine patrols with Coastal Command from RAF Beaulieu in Hampshire—a monotonous task according to Pee Wee Phillips. In all the time they cruised the skies over the Bay of Biscay, he never saw one submarine, ship or enemy aircraft. He relied heavily on his engineer McLean to keep his four Merlins firing while far out at sea and his Navigator Huey Huston to know exactly where they were at all times. This level of trust steadily built a fine and well-bonded crew. By the end of March, they were back in Bomber Command and posted to RAF Gransden Lodge in Bedfordshire as part of Pathfinder Force (PFF). The Pathfinders were an elite force of specially selected squadrons tasked with the accurate marking of targets at night so that the main bomber force would have a clear target to drop their bombs on.

Once part of PFF, the Phillips crew entered a long period of extremely intensive training for the task ahead—in particular for the pilots, navigators and bomb aimers. While on bombing operations with 405 Squadron, Phillips and his crew held a very specific task—which they called the “backers-up” as opposed to the primary target indicator crews. Other crews would be the primary target indicators, dropping coloured flare markers (usually red) while Phillips and other “backers-up” (about 6 crews) would come in afterwards with green markers (and sometimes incendiary bombs) which they would drop on the red markers to indicate the correct place or, if the red markers were not where they should be, drop the green markers on the correct target. The following bomber stream was to drop their bombs on the green. Of course, once they marked the target, they then returned on occasion and dropped their own incendiary bomb load on the green target indicators.

Related Stories

Click on image

A rare colour photograph of a 405 Squadron Halifax II being serviced and “bombed-up” prior to a raid. Photo: CanadianWings.com

Armourers of the RCAF’s 405 Squadron of Pathfinder Force, pushing carts of 1,000 lb. bombs, “bomb up” a Merlin-powered Handley-Page Halifax Mark II (LQ-Q) in Yorkshire. At right another armourer is fitting the release gear to Small Bomb Containers (SBCs) filled with 30 lb. incendiary bombs. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Pathfinder Force target indicators (TIs) drop from a Bomber Command PFF aircraft on their way to Berlin. TIs were also used to mark the route into the target to help lost or off-course aircraft find and align with the proper attack course. Photo: Imperial war Museum

Pee Wee and his crew were on Pathfinder operations for several months, which meant that inevitably they would have a “dicey do”. On the night of 3–4 July 1943, Phillips and 405 Squadron took part in a bombing raid on the German city of Cologne. Though Cologne was on the Rhine, it was one of the targets, along with other Rhine industrial centres like Duisburg, Mannheim and Dusseldorf, which were considered part of Bomber Command’s “Battle of the Ruhr”. According to the squadron ORB, eleven 405 Halifaxes were detailed to participate in a mass bombing raid of Cologne’s industrial area on the east bank of the Rhine River. 653 Bomber Command aircraft took part in the raid. A new German night fighter unit, Jagdgeschwader 300, using the “Wilde Sau” Messerschmitt Bf-109 tactics, brought down as many as 12 of the bombers on that one raid. Phillips’ Halifax was attacked by one of these 109s and suffered heavy damage on the run-in to the target. The squadron ORB details the incident: “One of our aircraft was identified by an unidentified night fighter and severely damaged the starboard elevator and tail assembly by cannon shells; cannon shell through starboard centre mainplane, wing internally damaged, fuselage holed and bomb doors shot up, and mid-upper turret and astrodome were holed.

Upon being hit, Phillips’ initial reaction was to dive and lose the attacker, which he did. Recovering, he continued on to the target and dropped his indicators. The damage caused by the Wilde Sau night fighter however produced major control problems for Phillips. The aircraft was wallowing all over the sky, climbing and descending. The only way to maintain pitch control of the Halifax was to tie a scavenged dinghy rope to the column and have two crewmembers pull on the rope when he needed extra strength to hold the column forward. Alternating pulling and releasing the rope, the three men managed to “fly” the Halifax to a safe landing at Gransden Lodge. For his quick thinking and airmanship, Pee Wee Phillips was recommended for and received the Distinguished Flying Medal, though he felt very strongly that the entire crew was involved in the safe return of the Halifax and should likewise be awarded the DFM.

The Night of the Great Storm

As Pee Wee and his now very experienced Halifax crew climbed out of Gransden Lodge and joined the head of the bomber stream en route to Hamburg, they had been briefed that there might be some bad weather en route to the target. They had no idea how bad. Pee Wee Phillips’ Halifax (RAF Serial number HR871, Squadron/Aircraft code LQ-B) was part of a massive raid (740 bombers in all—669 of which were four-engined heavy bombers (Halifaxes, Lancasters and Stirlings)) and was to be the last raid in a ten-day long and destructive series of daytime and nighttime raids on Hamburg. Called Operation Gomorrah, the raids were conducted by American “Mighty Eighth” Air Force of the United States Army Air Force by day and Bomber Command of the Royal Air Force at night. This night would be the last of three or four raids in which 405 Squadron was involved.

A port side profile drawing of Rolls-Royce Merlin-powered Handley Page Halifax LQ-B (HR871). Illustration by Paul Charland

Phillips headed east into the blackest of nights, crossing the North Sea south of Amsterdam then turning northeast to follow the coast of Holland, up around the Frisian Islands and their flak concentrations. Flying up the coast, the crew knew they were in for trouble. Heavy turbulence made the flying extremely uncomfortable and as they made their turn towards Hamburg, flying close to Wilhelmshaven and Bremerhaven, they could see a gargantuan electrical storm ahead, lit by flashes of lightning, like artillery fire at the front. In the intermittent flashes they could see that the bruised-looking cumulonimbus storm clouds towered to 30,000 feet, seamed by veins of lightning. They could also see that the malevolent weather astride their bombing run was too wide and too tall to skirt. There was nothing for it but to enter this meteorological hell.

As they approached the target, the Halifax was lit by blue-green flashes of lightning and tossed about like a light aircraft. Ice began to accumulate on the wings and the controls became increasingly more sluggish. St. Elmo’s fire could be seen building on the propellers and on the wing tips. One can only imagine the stress of the situation as these young brave men continued to do their work under these conditions. Close to the target, they were hammered by lightning—a deafening and explosive clap of thunder and searing flash of blinding electric light struck everyone senseless. As Phillips recalled in an interview with the Imperial War Museum many years later: “It was just one hell of an explosion, bits of aircraft flying all over the place. We were all blinded by it. Couldn’t see a thing.” They lost power to the two inboard engines as the surge instantly fried the electrical system as well as the radio. Pee Weealso lost all of his instruments except for the critical airspeed indicator. The blinding flash and the ensuing confusion caused Phillips to lose control of his Halifax temporarily. Fighting for control and with only two engines and no instruments, Phillips lost altitude quickly—from 19,000 to 8,000 feet in a matter of minutes before he got control. There was no way they could continue on to Hamburg to drop Target Indicators. Likely, there would be very few bombers that could get through this mess anyway.

While it might be possible to fly the Halifax on just two engines, the risks of doing so over the icy North Sea were too high to contemplate. Gathering his wits about him, he had Vern Knight jettison the TIs and asked Mainprize to work out a course to Sweden. His hope was to find an airfield to land at or to bail out over the neutral country.

Flying north over Denmark, they made Faxe Bay and found the waters between the Danish and Swedish coasts in the western Baltic Sea. At an altitude of just 4,000 feet, they were able to identify the lighthouse on the southernmost spit of land of Sweden, a place called Falsterbo. Continuing on a northeasterly track, Phillips flew on through the night for 60 or more kilometres. Turning 180 degrees over the lake areas of Ringsjön and Vombsjön and setting a new course on a southwesterly direction, he pointed the damaged Halifax bomber back towards the Baltic Sea where it would not hurt anyone and ordered the crew to bail out.

Holding her steady, trimming her for level flight, Phillips waited for his crew to leave the aircraft. Lloyd Kohnke and Joe King opened the floor hatch in the aft fuselage and dropped out into the night sky. Kohnke could have bailed out right from his turret at the tail, but it was likely that he had joined King in the fuselage as there was no need to watch out for enemy fighters over Sweden. Vernon Knight, Graham Mainprize and Ron Andrews followed in the forward compartment, jumping out through the escape hatch below Mainprize’s navigation station. Then McLean dropped down from beside Pee Wee to the lower crew compartments, stepped forward to the hatch and followed the others. Phillips was the only one left now. He carefully released his hands from their grip on the yoke, slid across to his right and stepped down to follow McLean. Seconds later he dropped away into the night, tumbling in the cool summer air. Above him, Halifax HR871, B-Beer, “his” Halifax, powered on through the dark night heading towards the western Baltic Sea. With only two engines running, she would have lost altitude, but trimmed up, she would have done so gradually.

All seven members of the crew landed in relative safety. There were some cuts and lacerations and Pee Wee had broken his wrist, but the only real casualty was a cow that was killed when Pee Wee Phillips landed on it when he came down by parachute.

Minutes after the entire crew of Halifax LQ-B were safely down on the neutral soil of Sweden, she crossed the coast between the ferry port of Trelleborg and Falsterbo at a place called Kämpinge Bay, still on a course that would take her back to Hamburg. She continued on for several miles out over the black and deadly waters of the Baltic. At sometime in the very early hours of 3 August 1943, the dark and shadowy form of a Halifax bomber running on only two engines, slammed unseen into the sea. She had carried her crew on many “dicey do’s” over the past couple of months and tonight, she kept them safe through terrible weather and brought them to their salvation over farm country in neutral Sweden. She held her own and kept them safe until all of her crew had left, and then with their seven souls departed, began her last, long let down to a watery grave.

We can never know how she hit the surface—did she come in almost level or stall low and spin in? However she came to strike the Baltic Sea, she did not entirely disintegrate. She broke up though and settled on the seabed, just 50 feet below the surface. When the sun came up on 3 August 1943, only fuel stains and minor debris marked her death and they were already miles away from where she had come to rest. There was a war on. Across Europe between September of 1939 and June of 1945 more than a hundred thousand aircraft fell from the skies from Swansee to Stalingrad. With her crew safe, no one cared to search for LQ-B and she lay alone and undiscovered on the seabed until 2011.

It Takes a Village to Raise a Halifax

There is a doctor near Hull, England by the name of Jeoren Pinto. Dutch by birth, “Jay”, as he is known to his friends, is “afflicted” by the same passion that motivates many of his fellow Dutchmen—he has an all-consuming interest in the history of the Second World War combined with a deep-set desire to honour those who participated in the liberation of his homeland from the black hands of Nazi Germany. In large part, this means honouring Canadians, for it was the Canadian Army that was tasked with driving the Germans out of Holland following the battles of Normandy. In particular, Jay Pinto is fascinated with the stories of airmen of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Such was his abiding passion that all of his friends and many of his patients knew this.

In 2011, one such patient, Gordon Dore, told Jay about a next-door neighbour in Hull who had been a Handley Page Halifax pilot during the war with the famous 405 “Vancouver” Squadron. It wasn’t long before Jay met Pee Wee Phillips and began recording some chats with him. Typical of many accomplished airmen of the Second World War, Phillips was reluctant to speak, worrying that he would be seen as a line-shooter. His concern was always to tell the story from the crew’s perspective and not as a personal triumph.

Jay was particularly inspired by Phillips’ story of the crew of LQ-B being hit by lightning and bailing out over Sweden. After his first meeting with Phillips, Jay’s curiosity had him typing in “Halifax”, “Sweden”, and “crash” into the search window of Google. Instantly he came across an article from six months previous in a Swedish English Language online newspaper called The Local. The article was entitled “Divers find WWII bomber off Swedish Coast”.

The divers, from an organization called Havsresan (translated as “The Sea Journey”), were part of a Lund University-funded cross-disciplinary series of expeditions to study the ocean environment in the southern part of Sweden, where Lund is located. They were conducting a dive on the site because the Swedish Coast Guard had registered something interesting on sonar scans of the seabed during routine training. The divers were expecting to find rock outcroppings on the flat sandy bottom, but instead they came across the remains of a long lost aircraft, possibly Halifax HR871.

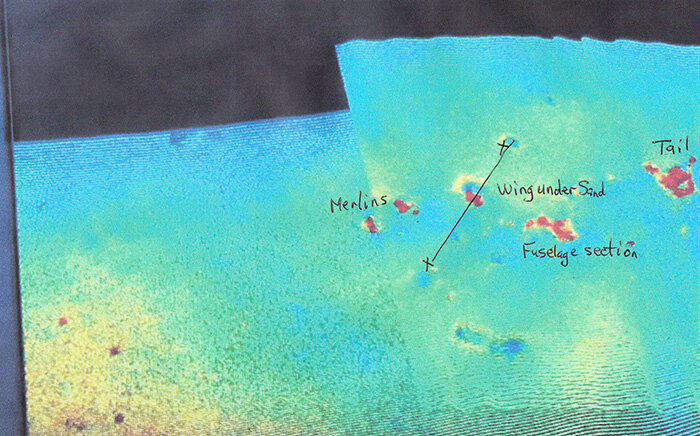

A sonar screen capture with notations showing the displacement of HR871’s body parts. Most of the Halifax is buried deep beneath silt and sand deposits. The team will begin this summer vacuuming away large volumes of sand and sediments to expose the historic artifacts beneath the surface. Photo: via Jan Christensen

The story in The Local mentioned the possibility of it being from a Halifax that had been damaged in 1943 and had been abandoned by its crew over Sweden. Jay was able to connect the scientists on the Havsresan team with the actual pilot, John Alwyn “Pee Wee” Phillips.

Pinto, who runs a fascinating commemorative initiative called the Gramophone Project honouring Canadian Second World War airmen, also had friends at the Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, Alberta, in particular Karl Kjarsgaard who also directs Halifax 57 Rescue Canada. It was Jay who informed Karl of both Pee Wee Phillips and the discovery of his Canadian Halifax. Jay made the introductions and Lund University made contact with Kjarsgaard and the rest, as they say, is history.

Though the Halifax that lies off the coast of Sweden was British-built and a Canadian bomber from 405 Squadron, the story of Swedish neutrality and its role as a safe haven for airmen in peril during the Second World War is an integral part of that country’s history and cultural heritage. Havsresan and their partners, the Swedish Coast and Sea Center, understand that recording and preserving their history does not just lay in Viking heritage and pure Swedish artifacts, but in the modern coastal and oceanic heritage and environment of Sweden.

The dive team from Havsresan and Swedish Coast and Sea Center discuss the dive. Photo: Havsresan via Jan Christensen

A few miles off the coast of Sweden, team members and divers from Havsresan and the Swedish Coast and Sea Center get ready to descend to HR871, lost to the world for nearly 73 years. The location is kept very secret to foil souvenir hunters and disreputable historic artifact dealers from looting the site. Photo: Havsresan via Jan Christensen

An astonishing photograph. After nearly 75 years at the bottom of the Baltic Sea, belted .303 ammunition looks intact and ready to fire sitting on the surface of the silted and sandy bottom. Likely this belt of ammo was carried aboard in a wooden box and the wood was eaten away leaving the folded belt. The Halifax bomber was defended by eight Browning .303 machine guns in fours—four at the dorsal turret and four at the tail. Some Halifaxes had twin .303s in the nose as well. Photo: Havsresan via Jan Christensen

One of Halifax LQ-B’s two rudders lies partially exposed above the sand at the bottom of the Baltic Sea. Once mapped, and after silt and sand are removed, the rudder will be brought to the surface where it will be assessed and treated. Photo: Havsresan via Jan Christensen

It’s a long way from Nanton, Alberta—Karl Kjarsgaard of Halifax 57 Rescue, project lead on the Canadian side, thrills to see the first photos coming in of component pieces like this Halifax rudder, lying on the sea floor. Photo: Havsresan via Jan Christensen

The first task for Havsresan’s divers, after assessing the displacement of the wrecked Halifax, was to lay down a grid on the sea floor to enable the entire site to be mapped prior to removal of sand and silt. Though Havsresan and The Swedish Coast and Sea Center, the Swedish partners of this aircraft recovery, are investing so much time and effort to recover a long-lost Canadian Halifax bomber, they rightly consider the site and the events that led to the wreck to be part of their Swedish heritage. While it might not be of the same national importance as the recovery of Viking artifacts, these dedicated men and women feel it is imperative to discover, record and, in this case, recover the archeological data and physical remnants of LQ-B. Knowing that these components will be absorbed into the rebuild of a functioning Canadian Halifax bomber will enable the Swedish history to be shared with the world. Photo: Havsresan via Jan Christensen

A well-preserved Browning .303 machine gun on the Baltic Sea bottom with its breech cover open. Last fired by either Lloyd Kohnke or Vernon Knight, HR871’s two gunners. Photo: Havsresan via Jan Christensen

Havsresan diver Tobias Melin strikes a Rambo-esque pose at the bottom of the Baltic Sea, holding one of the eight Browning .303 machine guns carried aboard Halifax LQ-B—in two electrically-operated quad turrets, one in the tail and one on her back. Photo: Andreas Vos, Havsresan

They also realize that the story of the Handley Page Halifax and their part in its complex and dramatic story can best be told if some of the components found below the surface can be raised and absorbed into the building of a real, functioning aircraft that will continue to tell the complex and honourable history of the type. Halifax 57 Rescue Canada has, for the past decade, been sourcing, acquiring and repatriating the components needed to build a Halifax which will be able to be started and taxied—a living, fire-breathing legacy to a generation of young Canadian men who served and died on the type. This is no wild unattainable goal. The museum already has one of only four Avro Lancasters in the world which have all four Merlins running, and they have already collected about 33 percent of the components necessary. Kjarsgaard himself spearheaded the full recovery of another Halifax from the bottom of 750-foot-deep Lake Mjosa in Norway. That Halifax has been fully restored and is the centrepiece of the National Air Force Museum in Trenton, Ontario. He also recovered another Canadian Halifax from a bog in Belgium and repatriated the remains of three Canadians. The aluminum recovered from that catastrophic crash was melted down to ingots, which were shipped to England. That aluminum was rolled into sheets which, today, form the roofing material of the Bomber Command Memorial in London, England.

As of this writing, multiple sets of new Halifax wing spars are being manufactured near Ottawa. Landing gear (actually from the Handley Page Hastings, the transport development of the Halifax) has been salvaged from scrap yards in Malta; seven Bristol Hercules engines (which powered later marks of the type) have been acquired, three of which are in superb condition; major sections of wing have been found as well as nose glazing and a rear turret.

A graphic representation of the progress made by the Bomber Command Museum of Canada acquiring parts needed for the rebuild of a working Handley Page Halifax. Parts shown in red have been acquired; parts in green/yellow have been located. Image via Bomber Command Museum of Canada

Beneath the sand off Sweden may be buried large components of a Canadian Halifax that are intact, or if damaged can, along with drawings, become templates for the rebuilding process. The Bomber Command Museum is now working with the Swedish Coast and Sea Center to inform, identify and encourage this enthusiastic group of Swedish heritage keepers.

Kjell Andersson (second from right, front row), the Jacques Cousteau of Sweden, is seen with his arm around Halifax 57 Rescue Canada representative Karl Kjarsgaard. Photo via Jan Christensen

Bring Pee Wee’s “Hallie” Home

In the end, Sweden, Canada and the whole world will benefit from the recovery of this old warhorse. But it takes considerable money to dive, assay, clear away 75 years of sand and silt and bring what is down there back to the surface. The energetic divers and scientists of the Swedish Coast and Sea Center and Havsresan are committed to its recovery and already they have been to the sea bottom to lay down a grid system for recording displacement of components and to take photographs.

Karl Kjarsgaard of Halifax 57 Rescue Canada has been to Sweden several times and the team is in place to begin the recovery. It is important that the team reach out to the aviation and historically-minded community and, through crowd-funding, raise financial support for our Swedish friends as they bring our heritage to the surface.

And when I say “our heritage” I don’t just mean Canada’s. While 405 Squadron was a unit of the Royal Canadian Air Force, many of its aircrew were Britons, Americans and Australians. Being the senior Canadian bomber squadron of the Second World War, and a unit of danger-fraught Pathfinder Force, members of 405 Squadron paid the heaviest price of all Canadian units (bomber or fighter) during the war. The death toll for 405 Squadron is hard to contemplate—750 airmen (pilots, navigators, bomb aimers, engineers, radio operators and gunners were killed in action from 1941 to 1945. Of these, 197 were from Great Britain, 22 were Americans serving in the RCAF and four were Australians—the remaining 527 were Canadian.

The terrifying and massive losses were not just those of a “hard luck” squadron, but were endemic to all of Bomber Command. Of all Allied military service units—Army, Navy or Air Force—the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command suffered the highest rate of death and injury. The aircrews knew it, yet they persisted in their profoundly unenviable task… to the death for many, and in the case of the surviving aircrew, without proper recognition for their service.

As Second World War dictator Joseph Stalin once said, “Quantity has a Quality all its own.” In no other Allied combat service of the war did this old adage apply quite like the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command of which 405 Squadron was an integral part. There were 125,000 aircrew members active in Bomber Command during the war. Of these thousands of young men, mostly volunteers, 55,573 were killed on operations, 8,403 were wounded in action and 9,838 became prisoners of war. The death rate was a breathtaking 44.5%. To put this into perspective, the United States Army Air Force’s 8th Air Force—the Mighty Eighth—had 350,000 aircrew members of which 26,000 were killed in combat—a 7.45% death rate, which was a terrible price to pay, but one that pales in comparison to that of Bomber Command. An airman of the Command had a worse chance of surviving the fight than a British officer in the hideous and obscene trench fighting of the First World War. The chance of surviving a full tour of 30 ops with a Bomber Command squadron was down to 16%. Even before operations, men were killed in training before joining Bomber Command—some 5,327 men met their deaths in training accidents alone.

If you randomly picked 100 airmen from the ranks of Bomber Command, 55 would have died on operations or later of their wounds, 3 would have been injured on ops, 12 would have been taken prisoner, 2 would have been shot down but would have evaded capture and only 28 would have survived one tour of operation. A staggering 364,514 operational sorties were flown by aircrews of Bomber Command, dropping more than a million tons of bombs and, in the process of duty, losing 8,325 aircraft of all types. Of the 55,573 men who were killed in action, 18% (more than 10,000) were Canadian boys. Of the 10,659 Canadian men killed in Bomber Command operations, nearly 70% were killed as part of a Halifax crew.

If you feel that we owe a debt of gratitude to the 55,573 young men killed in action in Bomber Command and want to be part of this historic recovery of Pee Wee Phillips’ beloved Halifax “B for Beer”, click on the button (https://fundrazr.com/campaigns/417498) and visit the Halifax 57 Rescue crowd-funding site for options and qualify for some great Halifax swag at the same time.

It is estimated that, even with the volunteer efforts of the Swedish teams, the full cost of recovering Halifax HR871 will be north of CDN $110,000. The fundraising continues as the first phase of the recovery, plotting and gridding the entire 50 by 50 metre site continues. Phase 2 is the excavation of many thousands of cubic metres of sand using a large underwater vacuum, exposing the remains of the entire bomber. Phase 3 will include the preparing and lifting of the Halifax airframe components from the bottom, and, supported by airbags, towing them to land to be conserved and preserved. With your help, Halifax HR871 will see the light of day once again, and if we are lucky… truly lucky, we may recover Pee Wee Phillips’ favourite seat cushion and return it to him.

Epilogue—The Fate of the Phillips Crew

When Flight Sergeant John Phillips came down by parachute in Sweden just after 2 AM, he had the misfortune of landing heavily on the back of a cow standing in a farm field near the village of Esarp, to the southeast of Lund. The force of the impact unfortunately meant the end of the bovine, but Phillips was relatively unharmed. After walking a while he managed to stop a milk truck driver and talk him into driving him to the large Swedish centre at Malmö, about 20 kilometres away. Here he reported to the police and later was reunited with all members of his crew who had been rounded up over the countryside. One can imagine his relief to see all of his crew alive and relatively healthy.

The crew was held briefly at an army facility where they were interrogated. The men were reluctant to divulge any information regarding their mission or unit, just the standard offering on name, rank and serial number.

The questioning over with, the seven airmen were transported hundreds of kilometres north to a special internment camp for airmen who had bailed out of damaged aircraft or landed in Sweden with stricken aircraft (usually Americans) from bombing raids in the north of Germany. The camp was near the town of Falun, Sweden, a little over 200 kilometres northeast of Stockholm.

The camp was relatively new, and the Phillips crew was one of its first “guests”. Then conditions were rough—meals were very poor and sleeping was done on a straw palliasse. The authorities there were not of the sympathetic variety according to Phillips. Still, they were allowed out of the wire enclosed camp each day and free to walk about.

Pilot John “Pee Wee” Phillips (Left, back row) stands with his crew and two Swedish chaperones inside the gates and barbed wire of Franby Internment Camp at Falun, Sweden. The crew had relative freedom if not much comfort. While the food was of poor quality and they were forced to sleep on a straw mattress, they were free to roam outside the gates by day, so long as they slept inside the wire at night. Front row, left to right: Unidentified Swedish chaperone, Ron Andrews, Graham Mainprize, and Lloyd Kohnke. Back row, left to right: John Phillips, Vern Knight, Herbert McLean, Joe King and unidentified chaperone. Photo via John Alwyn Phillips, DFM, DFC

Another photo of the crew in Swedish captivity, perhaps wearing clothing they were given by the Swedes. John Phillips occupies his favourite position in any group photo: far left.

Soon the camp was overcrowded with American B-17 and B-24 daylight bombing crews who had made emergency landings at Swedish airfields. The camp wasn’t big enough to accommodate all of them so, after several months at the internment camp, the Swedes commandeered a large house which had previously been a retirement home. Phillips and his crew were transferred to this facility, which was in a beautiful forested site. This was a great improvement over their previous conditions—better food and less regulation.

While at this new facility, the Royal Air Force attaché paid a visit to the home and during that time, he quietly intimated to Phillips that, if he could get himself to Stockholm, he would be able to spirit him back to England. There was a need for pilots, and this offer extended only to him. This meant he would have to leave his crew behind. After discussion with them, it was decided he would go.

In Stockholm, he was secretly whisked to the airport and put into the cramped bomb bay of a civilian-registered British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) de Havilland Mosquito. The “civvie Mossies” acted as high altitude, high speed blockade runners bringing much-needed quality Swedish ball bearing to England. It was a scheduled run from Stockholm to RAF Leuchars in Scotland and while the Swedes knew about the bearings, they may not have known about the secreted pilots aboard the occasional cargo flight. If they did, they turned a blind eye.

A “civilian” BOAC “Mossie” (G-AGGD) that worked the Stockholm to RAF Leuchars route. After several months at Framby, the conditions became overcrowded with American B-17 and B-24 crews who had diverted to Sweden due to battle damage or inflight emergencies. The Phillips crew was transferred to an old mansion in a nearby forest, which had one time been an old age home. The conditions there were considerably better than at Framby. Eventually, he was told by a British military attaché that if he managed to get himself to Stockholm, they could manage his flight back to Great Britain. It was all very “hush hush” as Phillips recalled in an interview for the Imperial War Museum, but he was placed in the bomb bay of a civilian registered de Havilland Mosquito, operated by British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC—the predecessor of British Airways), which was ostensibly used for high altitude, high speed delivery of quality ball bearings from Swedish manufacturers. He quickly found himself at RAF Leuchars in Scotland, but had to face lengthy interrogation from MI5 in London as he had arrived without passport, dog tags or any identity papers. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The bomb bay “cabin” of one of BOAC’s Mosquitos was not what we would call first class. The passengers, like John Phillips, were given an oxygen mask and strapped down inside the bay, which was lined with felt in an attempt to insulate the cavity. They were given a thermos of coffee and told to “hope for the best”. It was a good thing to be slight of stature like Phillips was, for the space was cramped and the flight long and uncomfortable. The Mossies were high flying blockade runners which could outrun any German aircraft at the time. Photo: RAF via “Merchant Airmen”, prepared by the Ministry of Information

Even though pilots and other agents were frequently carried by the BOAC Mosquitos both to and from Stockholm, the RAF intelligence folks at RAF Leuchars seemed surprised with Phillips’ arrival. Perhaps it was the fact that he had no identification whatsoever, not even dog tags, these having been confiscated by the Swedes and he was in civilian clothes. He was put under escort and taken to MI5 in London where he was thoroughly interrogated about his experiences in Sweden. After a brief period of interrogation, Phillips was granted leave to go home but was told, due to the fact that he had been a “prisoner”, that he would not be allowed to return to operational flying. His crew would be repatriated in a few months and be told the same thing.

Instead, he was assigned to No. 1658 Heavy Conversion Unit at RAF Riccall teaching new pilots the idiosyncracies of Halifax flying. With clapped-out and war-weary Halifaxes and ham-fisted student pilots, Phillips felt that instructional duty was more dangerous than combat flying. He remained at Riccall as an instructor from February 1944 until the end of March 1945.

Although he was told he could not fly operationally again, he got one more chance when he was posted to 78 Squadron at RAF Breighton in Yorkshire, flying Halifaxes at the very end of the war. He managed a few more ops, and was part of the last full Bomber Command raid of the war—the 25 April bombing of the Frisian Island of Wangerooge which had been heavily fortified and still had German coastal guns which controlled the shipping approaches to the ports of Wilhelmshaven and Bremerhaven at the mouth of the Weser River.

RAF/RCAF Lancasters of Bomber Command over Wangerooge, Germany. Photo: Imperial War Museum

After the war, Phillips remained in contact with his beloved crew and they met on occasion in Canada. He has always been reluctant to speak about the war, not because he has difficulty talking about it, but because he does not want to be seen as a “line-shooter”. Much of the information for this story comes from an interview with him and staff at the Imperial War Museum. At 95, he is the only living member of the crew of LQ-B, B for Beer. Soon, if all goes well, he will be reunited with his “kite”.