PER ARDUA — Life, Love and Courage

The American-French author Anaïs Nin once wrote that “Life shrinks or expands in proportion to one’s courage.” I believe this deeply. The most powerful feelings about family, love and the simple beauty of just breathing are paired with the greatest fears and danger. It is the soldier pressing his body hard to the ground in a slit trench during a mortar attack who understands the love of his mother more than any man. It is the wounded pilot fighting hard to keep his battered and smoking Halifax bomber steady for home on three engines who fully grasps the true nature of the love of his fellow crewmen. It is the young American boy who, slipping out of the cockpit of his Mosquito and taking in a deep, fragrant breath of Norfolk County evening air, feels the life drawn back into his body and, in so doing, understands the great incongruity of those contradictory bed mates—fear and life.

It is no wonder then, that combat veterans have difficulty adjusting to an ordinary life when they come home to places like Dauphin, Manitoba, Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia or Carleton Place, Ontario. To go from a rolling, scissoring dog fight high in the azure blue of a Belgian sky or from the heart-pounding headlong rush of a low level sortie across the polders and farmlands of Holland to the slow, clock-ticking, paper shuffling meaninglessness of a government office job or listening to the litany of complaints of unhappy customers in a shoe store is an unbearable contrast.

Family and friends assume the returned aviator will be overjoyed and grateful to have survived the tribulations, deprivations and obscene lethality of total war. They cannot fully understand the stresses felt by a young man or woman returning from all-out war to the ordinariness of peace. It is not the fear and death those young, beautiful people were addicted to. It is not the obscenity of war. It is not the extreme high stress of entering hell that they need. Rather, it is the deeply profound euphoria of coming OUT of hell that they seek. It is the powerful feelings of love and joy and living, intertwined with the fear and horror that they have become addicted to. The love of comrades. The unbridled joy of accomplishment. The profound power of shared hardship. The life nearly taken and then given back. The cold draught of life slaking the thirst of fear.

Courage is not the absence of fear, but rather the willingness to go forward in the face of fear. For people like me, the test of courage at this level will never come. Like any young man growing up, I wondered (and in fact still wonder at 62) if I had the mettle and the inner strength to survive such adversity and fear with an intact heart and mind. Or would I have the letters LMF put next to my name—Lack of Moral Fibre. As all of us did in our childhood, I acted out these scenarios, imagining myself a great hero, a brave young man, and a saviour of humanity. My imagination had me fighting Nazis from a foxhole, sending Teutonic killers down in flames or, wearing a white cowboy hat, riding a white stallion and spinning pearl-handled six-guns, saving the family of my neighbourhood dream girl from heartless burglars.

Thanks to the courage of our men and women in uniform in the Second World War and all conflicts since then, I will never find out about what I would have been like under these extreme conditions. Thanks to them, I will not have the burden of the memory of horror and loss either.

Over the past year, through a wonderful written relationship with a veteran of the Second World War, I have learned new lessons about this concept of courage. His name is Bob Kirkpatrick. His flying friends call him “Kirk”. He is an American who joined the Royal Canadian Air Force after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He trained right here in Ottawa at No. 2 Service Flying Training School at Uplands. He received his wings from none other than Billy Bishop. He went overseas and trained to be a multi-engine fighter-bomber pilot. He flew the beautiful and lethal de Havilland Mosquito with 21 Squadron, Royal Air Force. He took part in one of the most famous bombing raids of the Second World War—the low level, surprise attack on Gestapo headquarters in downtown Copenhagen, Denmark. He survived the war. Now, at 92 years old, he fights yet again.

One of Kirk’s good friends, an Englishman named Hugh Bone, who presently lives in Sweden had this to say about Kirk, whom he met at an Operational Training Unit:

“Kirk and I first met when we were on the same Beaufighter OTU at Crosby on Eden, No. 9 Coastal. We then did the No. 13 Mossie OTU at Bicester after which we were posted to 140 Wing, Kirk to 21 Sqdn and I to 487. After VE Day, volunteers such as Kirk, a Yank in the RCAF, were quickly repatriated and I lost touch with him but was re-united some 12 to 15 years ago through our connection to the Mossie Forum. Kirk was a natural born pilot and was really a fighter pilot destined to fight his war on twins. He went to the extremes with both Beau and Mossie, successfully performing aerobatics that were both forbidden and unadvised. I considered myself a pretty fair pilot but Kirk was better than most, I admired his skills and am honoured to call him a good and well loved friend...”

Bob Kirkpatrick’s course photograph from no. 13 OTU at Bicester, England where he and his mates converted to the de Havilland Mosquito after having just completed a Beaufighter course. Bob Kirkpatrick sits in the front row, second from right, while his navigator Wally Undrill stands directly behind him. To Bob’s right sits Hugh Bone, a fellow Mossie pilot on the course, who continues his friendship with “Kirk” to this day. Of Kirkpatrick, Bone says: “Kirk is a great guy and a natural pilot. He did things with both a Beaufighter as well as a Mosquito that experienced pilots with many hours on the type would never have attempted.” It is clear that each pilot on the OTU is sitting in a chair in front of his navigator, as the man behind Bone is Ken Guy, part of the Bone/Guy Mosquito crew. Sadly, Bone lost contact with Guy sometime after the war. Photo via Hugh Bone

A screen capture from film footage shot from Bob Kirkpatrick’s Mosquito as his squadron thunders across the English Channel on their way to surprise the Gestapo. RAF image

A rather poor screen capture from a blurry YouTube video. The camera film footage from the famous Shell House Raid (Operation CARTHAGE) in Copenhagen was all shot from the cockpit of Bob Kirkpatrick’s Mosquito. His normal “looker”, Wally Undrill was replaced for this raid by RAF camera man named Sergeant Raymond Hearne. What we see here is what Bob saw. RAF film footage

Related Stories

Click on image

Another photo from the Shell House Raid shows a Mosquito at roof top level. RAF photo

Happy to be alive and on friendly soil after the Shell House Raid, Kirkpatrick (left) and Sergeant Ray Hearne, the RAF’s cinematographer take a moment at RAF Rackheath to have their photo taken. Photo via Bob Kirkpatrick

Needless to say, courage was something he and his comrades had in spades, as every one of these accomplishments was paired with great personal risk and the steady erosion of squadron mates to death and capture. Regardless of the risks, which they knew full well, they pressed on, fueled by a blend of skill, invincibility, fatalism, pride, duty, honour, testosterone and love for their comrades.

When the war was won, millions of men and women, like Kirk and Hugh, put down their weapons, collected their demobilization papers, signed the paymaster’s form one last time, hung their battle dress in the closet, and began the surprisingly difficult process of settling back into a workaday world they had left years before. Highly skilled fighting men, with recent memories of crossing the Atlantic, seeing Liverpool, Paris, London, Piccadilly, Essen and Berlin now looked upon Des Moines, Iowa; Davidson, Saskatchewan and Truro, Nova Scotia and tried to put everything in perspective.

For the majority of returning military pilots, their final Return to Base or their last, mad, sightseeing dash across Germany after the war to see the devastation, would be the last flight they would ever take the command seat for. Aviation, though it had occupied their every waking hour for years, no longer found itself with the same importance—life, love, family, business, education, income and memories of terror all played into the fact that most pilots and aircrew put flying behind them. Some, however, would continue to fly—as regular air force pilots, in the reserve units, or as commercial airline, crop-dusting or bush pilots. A tiny fraction was still flying in combat as late as the Vietnam War.

Bob Kirkpatrick and Hugh Bone both declare themselves, in a gentle self-deprecating manner, as “tail-enders”, men who came late to the war and whose contribution paled in comparison to others. These of course are the voices of humble men who have sworn to some unspoken oath which states that the terrible things that happened to them during the war, that the deaths and injury to their friends and their shared sacrifice would be dishonoured if a man were to brag or gain heroic status by self aggrandizement or self-promotion. In fact, Bob Kirkpatrick began his service in 1942, following a path that lead him to night and low-level daylight intruder operations on the magnificently agile, mightily powerful and beautifully sculpted aircraft known as the Mosquito—the Wooden Wonder.

Though they call themselves “tail-enders”, Bob and Hugh were well into the fray by the fall of 1944. Of his more than three years in the RCAF, Kirkpatrick trained and flew on operations for almost two years. He flew 24 combat operations over enemy territory and he flew in one of the most talked-about low level raids of the war—the attack on Gestapo headquarters in Copenhagen known as the Shell House Raid. By the end of the war, nearly everyone was a “tail-ender”, as most of the old timers had completed tours, gone home, been injured, were in POW camps or had been killed on operations and in training. One thing is for sure, when he was de-mobbed in August 1945, Bob Kirkpatrick did not yet have his fill of flying. Not by a long shot.

When Bob Kirkpatrick crossed into Canada to join the RCAF in 1942, he would not see his homeland until late 1945. Without an American service record or passport, he was no longer believed to be an American citizen when he tried to come back in to the US with his new bride Ginny. Then Bob remembered his American Red Cross Officer’s Club membership card: “I carried it in my billfold and when we were returning to the States from our honeymoon and release from the RCAF at Lachine, we were stopped at the border at Niagara Falls. Customs saying I was not a citizen of the US and wasn’t allowed in. I remembered this in my billfold , presented it and said the American Red Cross says I am a citizen. They let me in and it was 19 years later when the subject came up again and I had to go to court prove my citizenship.” Photo via Bob Kirkpatrick

While Bob would never see another Mosquito fly from the time he slipped out of the starboard side crew door of the 21 Squadron Mosquito he was allowed to fly back to England on his way home, until this year, he would go on to a flying career totaling some 20,000 hours, and none of it drilling a hole on the sky as an airline pilot. Bob returned home to find his high school sweetheart Ginny waiting for him. He settled in to a life in the peace and prosperity of postwar America.

Bob had feet that were meant to roam however. Over their nearly 70 years of marriage, Bob and Ginny moved around the Midwest, occupying no fewer than 26 separate homes. After the war, he acquired three surplus Navy Stearmans from Wichita Falls, Texas and ran a crop spraying operation but, for much of his life, he used his Piper Chieftain and Beech Baron and other company aircraft to deal in cattle. Throughout his life, Bob Kirkpatrick made sure he made time to enjoy the hard won peace he fought for. Every month he would set aside a week to roam, to fly, to fish (from James Bay to Chandeleur Island in the Gulf of Mexico), or relax in the Bahamas. Having hung his toes over the edge of the abyss during the war, the former Mosquito pilot had a sense for how to extract the best from life. Having seen what he had seen and done what he had done, he was never going to let himself slide backwards to mediocrity.

Bob’s business card from the 1980s shows how proud he was to be a pilot and how fatalistic he was about being a cattleman. Image via Bob Kirkpatrick

Bob (left) loved nothing more than to get in one of his airplanes and fly to where the fishing was good. Here, he and his son John display the catch of the day. Photo via Bob Kirkpatrick

Courage is not the purview of youth.

My friendship with the elegant Bob Kirkpatrick began as an email question from him relating to a story on this very Vintage News site. I am not entirely sure how Bob Kirkpatrick came to be a subscriber to our weekly story service. Perhaps he was one of the thousands of email addresses I have shanghaied around the world and pressed into service; perhaps he signed on willingly. Shortly after publishing a story entitled Rock of Ages, about the discovery of new (to us) photographs of Flying Officer Rolland “Rocky” Robillard, for whom our P-51D Mustang is dedicated, I was contacted by Kirkpatrick with a curious question, one for which we have never really found an answer. He wrote: “A note of appreciation to the folks at Vintage Wings. I enjoy your frequent emails and stories. Particularly this Rock of Ages. I received my wings in June 1943 at Uplands, # 1 Squadron. Robert Kirkpatrick, J27206. While in the RCAF, can’t remember when, but possibly during my time at Uplands, I had heard about an evasive fighter maneuver, the Robillard Roll. The following is from a housebound 90+ year old whose memory is often questioned. However, it seems that the Robillard Roll consisted of a feint vertical bank to the left followed by full stick forward, like a bunt when straight and level, followed by a roll to the right, back to a vertical left bank. Apparently this could end up with the pursued becoming the pursuer. Has anybody heard of this or performed it? Anyway, thanks to Vintage Wings, keep those e-mails coming.” – Kirk

And so began a winter long correspondence. It was through this correspondence that I came to know Kirk and a little about his story. I began to consider him my friend, as we shared feelings and vignettes of the things in our lives that were dear to us, like our wives, dogs, children and travel. Over the winter I learned that this articulate, passionate and humorous man was 92, and that his health was in serious jeopardy. Bob is a private man, and he was not instantly forthcoming about his long fight with cancer. But now and then I could detect that he was suffering from some very serious pain issues and at times had difficulty writing on the computer. Regardless, Bob was not going let this to stop him from speaking about the beauty of his life and the characters, dogs, aircraft and adventures that coloured his long and satisfying life. I won’t go into this much further, but understand that Bob Kirkpatrick, despite his 92 years and constant pain, was full of happiness, pride, warm feelings, good humour and above all courage.

At 92 and in pain, you could understand if a man simply allowed himself to fade away, to stop his engagement with the world he lives in. This did not happen with Bob. He simply took some medication and reached out via the internet to old friends like fellow Mosquito pilot Hugh Bone and new friends like me. Together, we followed the developments of the Av Spec Mosquito restoration in Ardmore, New Zealand, shared our life’s small pleasures and enjoyed each other’s company, even if it was a tenuous electronic link. As the Mosquito story grew, Bob seemed to be the first with new images and videos of the roll-out and flight testing.

Sometime in the middle of February, I learned that the Yagen Mosquito was going to make an appearance at the Hamilton Airshow at the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum. I had it in my head that it would be such a wonderful thing for him to come to the show and see his old sky-dancing partner one more time. I posed a question to him, even though I knew he was suffering and sometimes bed ridden: “Would your health preclude you from going to the Hamilton Airshow to see the Mosquito?” I truly thought he would decline, but he left a window open immediately: “Probably, but I won’t say I can’t. Who knows what the future will bring? If OK, I would need a golf cart or such I’m only good for 100 ft or so walking with a walker. You have presented me with a pleasant dream.”

I nearly cried.

Over the next few months a plan began to take shape, one that was entirely out of my hands. Bob and his wife Ginny have a pair of neighbours about the same age as their own kids—Deb and Dave Dodgen. Dave, a pilot and multiple aircraft owner, hog farmer and agricultural land appraiser, uses his aircraft in much the same way as Bob once did in his feeder cattle business. Dave and Deb originally thought that they would fly Bob to Hamilton, but soon Bob and Ginny’s comfort became the most important factor if this was to happen. The Dodgens came up with a new and astonishing plan—they would purchase a new Born Free recreational vehicle and drive Bob and Ginny all the way from Humboldt, Iowa to Hamilton, Ontario! The trip would take 6 days and cover more than 3,000 kilometers!

Per Ardua

Flying Officer Bob Kirkpatrick was an officer and a pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force. He is, today, very proud of this fact and of his service and his Canadian wings. The Latin motto of the Royal Canadian Air Force and in fact all Commonwealth Air Forces, is Per Ardua ad Astra, which, in English, means Through adversity, to the Stars. So completely different than the more aggressive, jingoistic and somewhat less poetic motto for the USAF, Aim High ... Fly-Fight-Win, this Haiku-like sentiment of the RCAF remains a perfect and poetic phrasing of the work, risks, losses and ultimate victories of this remarkable and storied service. It is deeply beautiful in that it lays out, in two simple and contrasting halves, the powerfully contradictory Latin root words of “Ardua” and “Astra”. This balance, this admission of the existence of both the horrors and the glories, is sublime.

It is a motto that could be the personal motto of Flying Officer Robert Kirkpatrick, as he processed his beautiful life to this date. Bob learned early on that Ardua came with Astra, hell with heaven, work with play, loss with joy, pain with love and fear with courage. Bob embraced the difficulties of life for the sweetness of their overcoming. This is the true nature of all experience, not just in times of war. It took a man who I had never met, a man from the heartland of America, not Canada, a man of 92 years and an uncertain future, to show me that courage can be called for and answered throughout life and not just, as we often think, in times of war. And that is when I thought of the words of Anaïs Nin—“Life shrinks or expands in proportion to one’s courage.”

No one could fault a 92-year-old man fettered with a continuous pain management regimen, if he declined an invitation to attend an outdoor airshow in the heat of summer, nearly 1,000 miles away. But Bob Kirkpatrick is a 92-year-old man on the outside, and a virile 24-year-old on the inside. He still thinks like a young man. He still looks out upon life as a young man. He saw that the pain, the work, and indeed the risks, if faced, could pay out in silver dollars—in one more life-confirming experience, one more time to see an old gal named Mossie, The Queen of the Skies, who once took him to Hell through the Ardua and brought him back to enjoy seventy years of stars at night and more than 25,000 sunrises.

He had the good fortune of two amazing neighbours who took up the challenge, the Ardua, with him, so that Bob and they themselves could eventually look up at the blue Hamilton sky, surrounded by the Astra of life. The stars this time would take the shape of a de Havilland Mosquito fighter-bomber surrounded by a constellation of warbirds.

It was good fortune to have Dave and Deb living right next door, but it was fortune of his own doing. He and Ginny are delightful and forthright human beings and the Dodgens grew to love them like family.

So, as the day drew near, I found that the impossible was about to happen. My friend, albeit one I had yet not met, was on his way, laying back in the air conditioned “private jet-like” comfort of a motorhome as it raced across the cornfields of Iowa, bound for a reunion with an icon, a celebration of life and friendship—one more glorious adventure in the life of a Royal Canadian Air Force pilot.

Here’s to Bob Kirkpatrick and the people who love him.

En route from Humboldt, Iowa in the Born Free motorhome, the adventurers were comfortable and able to support Bob all the way with encouragement and love. Left, Dave Dodgen, “Our Pilot”, gives a thumbs-up rolling eastward on the interstate, while in the back, Bob rests and enjoys the company of his high school sweetheart Ginny. Dave is himself a pilot and son of a US Navy aviator. He owns a Beech Bonanza and another aircraft. Photos: Deb Dodgen

Volunteer John Coleman proved to be an invaluable man to have around that day. John is a member and volunteer at Vintage Wings of Canada as well as the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum. With his knowledge of CWHM and his uniform, we had no problems getting anywhere. He hung in there all day and made us all feel welcome and at home. When I first told John about Bob’s visit several months ago, he signed on to help immediately. Here he assists Bob, who was loaded with gifts from organizers, on his arrival at CWHM. Photo: Deb Dodgen

There was standing room only at the Mosquito Memories event. People were there to see the magnificent machine, but also to be in the presence of her pilots, navigators and maintainers when they were reunited. Photo: Peter Handley

A large crowd of veterans, their families and interested people were in attendance, and Bob took up a position on the edges. In the background stands Jerry Yagen’s Messerschmitt Me 262. There was a time when Kirkpatrick would have to be very wary of the Luftwaffe’s jet fighter, but today, his attention was focused on the de Havilland Mosquito in front of him. Photo: Richard Mallory Allnutt

Despite his worries and his constant pain, Flying Officer Bob “Kirk” Kirkpatrick was a happy man this day, surrounded by his comrades-in-arms once again, flanked by people who loved him and in the company of his beloved and beautiful Mosquito one more time. Photo: Peter Handley

There were a number of speakers at the Mosquito Memories event—the builder, the Military Aircraft Museum’s chief pilot, CWHM leaders and a couple of veterans. Here, one of the most famous Mosquito pilots of all time and an ace, Russ Bannock speaks about his experiences. Bob was particularly looking forward to having a chat with Bannock. Photo: Peter Handley

There were many people in attendance and quite a few multi-generational families. Here, a young great grandson hand-flies a diecast Mosquito toy to while away the speechifying, while dad and great granddad listen to the guest speakers. Photo: Peter Handley

There were many Mosquito operations veterans in attendance, including Distinguished Fly Cross recipient Norman Griffiths who was both a Mosquito Navigator and a Pilot. Photo: Peter Handley

Bob stands along with fellow Mosquito veterans to be recognized by all in attendance. Photo: Peter Handley

Bob Kirkpatrick doffs his RCAF cap in recognition of the applause from the crowd. Bob, along with fellow American Bill Siler, were also asked to stand up as the two American Mosquito veterans in attendance. Photo: Richard Mallory Allnutt

Some photos say many things. To me, this one says pride, happiness, sadness, time passed, sorrowful memories of comrades, happy memories of a life at the peak of personal experience and, above all, strength of the human spirit. Photo: Richard Mallory Allnutt

These extraordinarily dignified veterans of Mosquito operations were given front row seats for the event. Photo: Peter Handley

Two more dapper men could not possibly be found. As Gerald Haddon (left) will tell you, it was an honour to accompany or be associated with a Mosquito veteran at this event. Here, he is with his good friend Squadron Leader Larry Henderson, a Mosquito pilot from the Burma Campaign, who incidentally was shot down three times. One can imagine the difficulties maintaining wooden aircraft in the damp monsoon periods and sweltering heat of Burma. Photo: Peter Handley

Warren Denholm (centre), of Mosquito builder AVSpecs Warbirds Restoration, talks to the assembled veterans, families and historians about the honour attached to building the world’s only flying example of the once ubiquitous de Havilland Mosquito. Photo: Peter Handley

Christopher Wilkinson of the United States purchased a vintage de Havilland Mosquito crew door online, than had a unique idea. He would send the door to as many living American Mosquito crew members he could find and have them sign the artifact. He managed to find six survivors who flew with the RAF, RCAF and even with the rare USAAC Mosquito squadrons. One of those was the RCAF’s Bob Kirkpatrick of 21 Squadron, RAF. Wilkinson’s dream was to collect as many of these signatures as possible, then donate the door to be on display at Jerry Yagen’s Military Aviation Museum (MAM). The other signers were: Richard Tyhurst – 25th Bomb Group, Robert Hastie – 25th Bomb Group, Jack Sheen – 25th Bomb Group, Roland Bushner – 25th Bomb Group, James “Lou” Luma – 418 Squadron RCAF, Richard Hoover – 416th Night Fighter Squadron USAAF

The hand-painted air force armorial crests included 21 Squadron RAF, famous for their participation in the great Shell House Raid of Gestapo Headquarters in Copenhagen. When Christopher Wilkinson had collected his signatures, he sent the door to the MAM in Virginia Beach, where it was put on display for their airshow. Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum traded an appearance of their Lancaster at Virginia Beach for an appearance of the Mosquito at Hamilton. While at the MAM event, CWHM agreed to fly the door back with them to Hamilton and to put it on display during the Mosquito Memories event. It was given a place of honour under the wing of the Mosquito, where it received a lot of attention.

Bob points to his name and 21 Squadron badge on the Wilkinson Mosquito crew door. Photo: Peter Handley

“We did it!” Dave Dodgen and Bob Kirkpatrick celebrate with a firm handshake and big smiles at the result of a committed friendship and a lot of planning. They bought a motorhome for the single purpose, drove 2,000 miles there and back, and shared the road for 6 nights. All for the love of a very fine man—who is both a Canadian and an American hero. Photo: Peter Handley

A little bemused by all the attention and flashes going off, Kirkpatrick allows a swarm of photographers to close in on him. Photo: Richard Mallory Allnutt

One of two former Mosquito air crew members in attendance who were Americans, was Bill Siler, who flew recon Mossies with the 653rd Squadron of the 25th Bomb Group of the United States Army Air Force. Bill Siler, at 97 years of age, is a study in longevity and determination. The near-Centenarian drove himself to the Mosquito Memories event FROM CARMEL, CALIFORNIA!!!

Bob and Bill share a moment together. Photo: Peter Handley

The diminutive but feisty Siler and the lanky and proud Kirkpatrick pose together. When I asked Siler what was the secret behind his longevity and get-up-and-go, he looked me in the eye and said, “I follow the bible...” and just as I was thinking to myself “Here we go”, he added, “... where it says ‘Only the good die young!’ ” Photo: Peter Handley

Left: The man whose idea it was to create the Mosquito Memories event was Dave Pridham of Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum. Here, Dave asks Bob Kirkpatrick to sign his Mosquito ball cap after the formalities were over. The event was a spectacular success with more people attending than originally planned for. We, at Vintage Wings of Canada, would like to commend Pridham for this grand gesture to our veterans of Mosquito operations and the success of this emotional and rare event. His love of history and pride in our veterans send the right message about why we do this in the first place. Photo: Deb Dodgen

Right: Bob looks into the crew compartment of the Mosquito through the tiny crew door. One can only imagine the thoughts pulled from his memory of the hundreds of times he squeezed his lanky frame through that small opening and slid his 6’2” body into the pilot’s seat, there to remain for hours and hours until the mission was complete. Photo: Deb Dodgen

Bob sat in his walker/chair, held court, answered questions, signed autographs and met new veteran friends. Photo: Peter Handley

With the door open, visitors (including Vintage Wings Hurricane pilot, Joe Cosmano) lined up for a look inside the magnificently restored Mosquito. Everyone was amazed at the tight crew confines of the fighter-bomber. Photo: Peter Handley

Bob shows us the small crew door that he and his navigator (“looker”) would have to crawl through to get to their seats in the Mosquito’s cockpit. At 6’2”, it was a challenge for Bob back then. While he did not try to get in, you could see him thinking about it! Photo: Peter Handley

The Humboldt Four pose for the camera in front of the de Havilland Mosquito—Bob Kirkpatrick, Deb Dodgen, Ginny Kirkpatrick and Dave Dodgen.

92-year-old Bob Kirkpatrick and his high school sweetheart Ginny pose with his other love—the de Havilland Mosquito. Photo: Deb Dodgen

After the Mosquito Memories event, Bob and Ginny pose for a photo in front of the Museum’s front door. Vintage Wings of Canada would like thank Dave Pridham and the CWHM for their spectacular and emotional tribute to the Mosquito crews of the Second World War—Well Done. Photo: Deb Dodgen

The kind folks at Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum gave the Kirkpatrick entourage a prime parking location, right at the front doors of the museum, allowing Bob easy access to the motorhome to rest. Photo: Deb Dodgen

The two Daves (Dodgen and O’Malley) enjoy the company of Ginny and Bob Kirkpatrick. The motorhome was the perfect idea to get Bob all the way to Hamilton in comfort and, as it turned out, a perfect way for new friends to have a couple of bourbons and get to know each other. Photo: Deb Dodgen

After the Mosquito Memories were over, we accompanied Bob and Ginny back to the motorhome so that he could rest prior to a late day flypast. Instead, a party broke out. Photo: Deb Dodgen

Out on the ramp, the “Mossie” is getting ready for a formation flypast practice session. Photo: Peter Handley

The warm-up for the flypast begins with the Mosquito’s Merlins firing up in spectacular fashion. Photo: Peter Handley

Six Merlins come to life. Preparing for the formation flypast of 6 vintage Rolls Royce Merlin-powered aircraft, the Mosquito and the Lanc warm their engines on the CWHM ramp at Mount Hope. Photo: Peter Handley

Vintage Wings of Canada participated in the Merlin-powered flypast for the Mosquito Memories event with our Spitfire XVI and Hurricane IV. Here, VWC pilot John Aitken keeps cool by opening his door and canopy while he warms the engine. Photo: Peter Handley

Rob Erdos in the Hawker Hurricane joins the action. Here, we can see the scores of photographers assembled on the observation deck in the background. Photo: Peter Handley

Bob, family and friends look into the distance as the formation flight approaches for a sweeping and thundering flypast of the ramp outside the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum. Photo: Robin Mallory Allnutt

Now in perfect alignment, the moment arrives. Bob will see a Mosquito fly for the first time since he stepped out of one after delivering it back to Bournemouth, England from Europe after the war. Photo: Peter Handley

As the world’s only flying example of the de Havilland Mosquito approaches in the company of a Lancaster and British Fighters, one can only imagine the memories of days and friends long gone that course through Bob Kirkpatrick’s mind. Photo: Richard Mallory Allnutt

The Lancaster, flanked by Spitfires, Hurricanes and the Mosquito, makes a long majestic approach to the ramp of the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum, as Bob Kirkpatrick and hundreds of photographers below watch in awe. Photo: Peter Handley

A perfect formation. Flanked on all sides, the Mosquito’s first real appearance in Canada was a dramatic one. One veteran at the Mosquito Memories event quipped that the elegant Mosquito was considered a bomber in the presence of fighters and a fighter in the presence of a bomber. In this formation, it was simply a superstar. On the right, Vintage Wings pilot John Aitken flew the lead Spitfire with Rob Erdos in the Hurricane Mk IV behind him. Three of the aircraft in this formation were built right here in Ontario—The Hurricane XII (Canadian Car and Foundry at Thunder Bay), the Avro Lancaster (at Victory Aircraft at Malton) and the de Havilland Mosquito (at de Havilland Canada at Downsview). Photo: Deb Dodgen

The observation deck of the CWHM was crowded with photographers. It is evident that a few of them were so awestruck by the flypast that they forgot to train their cameras on them. Photo: Peter Handley

One last flypast to the north of the field—a practice flight for the next day’s airshow. Photo: Peter Handley

After the flypast, Peter Handley shows Bob the results of his photography and all are surprised by the geometric perfection of the 6-ship formation of dissimilar types. Photo: Robin Mallory Allnutt

Bob’s stamina amazed us all. The evening of the Mosquito Memories event found dining al fresco on the shores of Lake Ontario in Burlington as the night overtook us. Around the table, clockwise from Bob Kirkpatrick, are Ginny Kirkpatrick, Peter Handley, the author, Dave Dodgen and Deb Dodgen. Photo by our waitress

Bob meets Gavin Lee (centre), RCAF Search and Rescue Technician and, on the weekends, a part of the Scheyden aerobatic team. Bob, at 92, was still the equal of Lee, the hypersonic, athletic, manic para-rescue jumper and uber-friendly former comedian-in-residence at Vintage Wings of Canada. Photo: Deb Dodgen

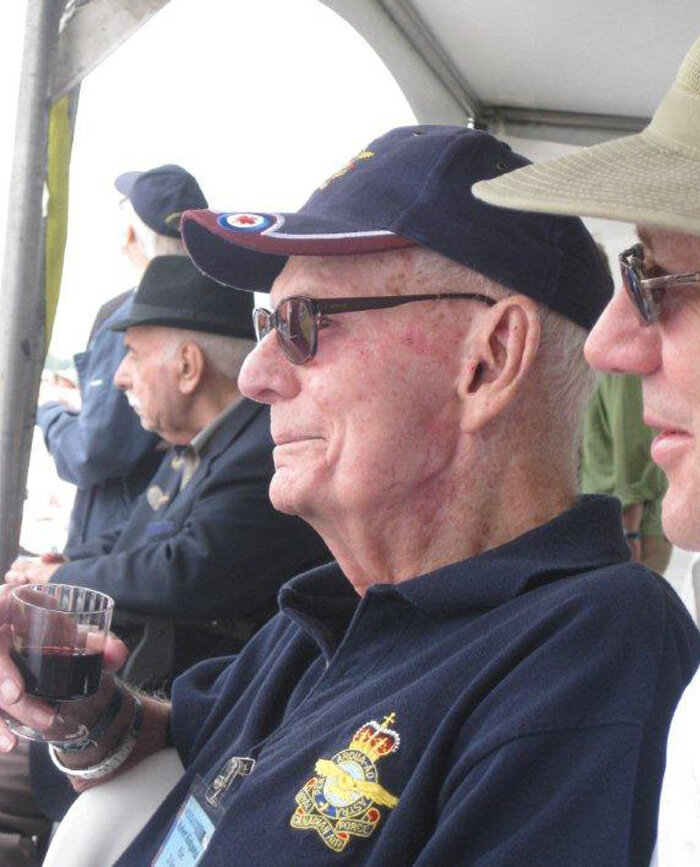

Flying Officer Bob Kirkpatrick enjoys the company of friends, a glass of red wine and the presence of mighty aircraft. While many folks who attend these shows and sit beneath the tent never look up at the show, Bob and Dave and Deb were there to see everything and were enthralled by the flying demonstrations. In this photo, you see two things that differentiate him from every other American… he is proudly wearing the badge and hat of the Royal Canadian Air Force, with which he served with such distinction during the Second World War. The words of the badge say it all—Royal Canadian Air Force—Per Ardua ad Astra. Photo: Deb Dodgen

The Humboldt Four enjoy the airshow with cold beer and red wine close at hand. Photo via Deb Dodgen

Bob and Ginny enjoy a brief stop at the edge of Niagara Falls before the start of their two-day journey home. Photo: Deb Dodgen

Niagara Falls from the window of the motorhome on the return trip. Photo: Deb Dodgen

Though this photograph taken on Deb’s phone is small and blurred from the motion of the rolling motorhome, it says it all: Bob, looking happy and strong, and Ginny, happy and relieved, offer a toast to a “Mission Accomplished”. We, at Vintage Wings of Canada and the volunteers at Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum, offer our deepest thanks to Dave and Deb Dodgen for making the impossible possible. Photo: Deb Dodgen

The best day of my summer. I finally get to shake the hand of, hear the voice of, and put my arm around a good friend—Flying Officer Robert “Kirk” Kirkpatrick, Royal Canadian Air Force. Bob, if I have told too much here, please forgive me. Photo: Peter Handley