OPERATION CHASTISE — At 70 Years

Photoshop Illustration by Dave O'Malley with Richard Allnutt photograph

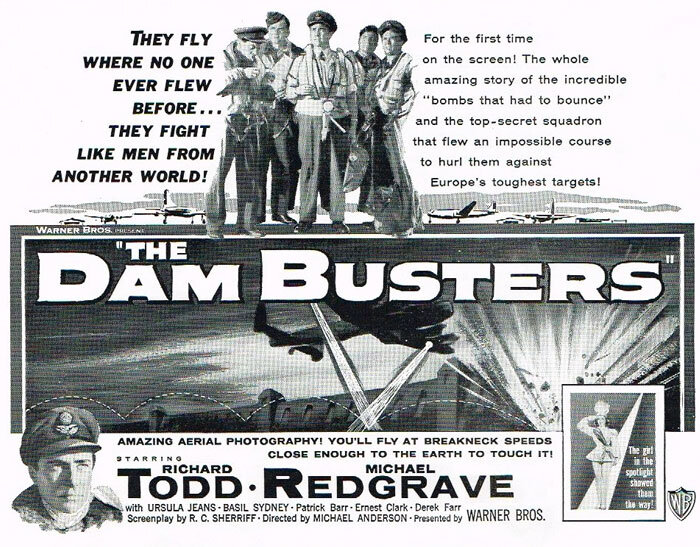

In the seventy years since the night of 16–17 May 1943—the night of Operation Chastise—the events that transpired on that moonlit spring night have been made into feature films, documentaries, novels, non-fiction books, magazine articles, dramatic paintings, computer games, marches and comic books. For all of you who read this, there is not much one can say to add to the reportage of this stunning attack deep inside Germany on targets long thought to be unassailable.

On that dark night, lit only by the moon, 133 very young men of 617 Squadron took off in 19 specially modified Avro Lancaster bombers, formed up and flew extremely low over the English Channel across the Dutch coast. Having trained for months to deliver a very special weapon, the young men were headed for a date with destiny. The aircraft were to fly low, beneath radar coverage, navigate deep into Germany, locate and attack a series of massive dams on tributaries of the Ruhr River. Behind each of these dams, the Möhne Dam, the Sorpe Dam, the Eder Dam and the Ennepe Dam, were massive reservoirs of water which, it was hoped, would flood factory sites downstream and bring much of Germany's industrial production to a standstill.

The attacks would be carried out using a special explosive device which, when released from a Lancaster bomber at exactly 60 ft AGL, at exactly 240 mph and at a specific distance from the reservoir-side face of the dam, would fall to the water and then bounce like a skipping stone, in decreasing bounces, until it fell exactly at the face of the dam. The bombs would then sink down the face of the dam to a specific depth where a hydrostatic sensor would detonate the bomb like a depth charge. And like a depth charge, the bomb would use the power of compressed water to deliver a devastating blow deep beneath the surface, weakening the dam's structural integrity. The massive weight of the stored water would then breach the weakened dam wall and roar down the valleys, flooding industrial complexes downstream.

The squadron was made up of hand-picked crews under the leadership of the charismatic 24-year-old Wing Commander Guy Gibson, a veteran of over 170 bombing and night-fighter missions. These crews included RAF personnel of several different nationalities, as well as members of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), who were frequently attached to RAF squadrons under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. The squadron was based at RAF Scampton, about 5 mi (8 km) north of Lincoln. The crews found their targets and, facing heavy flak and cannon fire from the dams' batteries of anti-aircraft guns, they pressed home their attack, with only the moon to guide them. Of the 19 participating aircraft, 8 were shot down. Of the 133 men involved, 53 were killed. Of the 53 killed, 15 were Canadian. There was one Victoria Cross (Gibson), as well as five Distinguished Service Orders, 10 Distinguished Flying Crosses and four bars, two Conspicuous Gallantry Medals, and eleven Distinguished Flying Medals and one bar given out for service on that one night alone. 17 members of the Royal Canadian Air Force survived, 16 of them were Canadians and one was an American.

The story of the DamBusters is well told, in every form. But we ask that, on 16–17 May, you take a moment to imagine you're one of 7 young Canadian men hunched in the dark, thundering down a flat expanse of cold, black water, deep in the heart of an evil empire on a moonlit night. The hills around you are filled with armed men who wish to kill you. Imagine the roaring sound of four Merlins thundering at 240 mph, just 60 feet from death. Imagine the flash of tracer fire, the hellish vibration of the Lancaster, the icy air, the explosions, the grim determination, the shaking hands, the stench of sweat, gas, oil and death, the sound of the bomb spinning up beneath you and then releasing, the gut wrenching pull up, the shells and hot metal shrapnel smashing through the thin aluminium skin all around you. Imagine the steady voice of the bomb aimer in your headset, muffled yet high-pitched from fear. Imagine the Lancaster in front of you exploding as it passes over the dam. Imagine swimming upstream against a flow of deadly tracer, trained on your face, on your body, on your friends. Imagine your family 6,000 miles away. Imagine it was you in the front of that fragile, thin-skinned, yet screaming Lancaster.

Then ask yourself if you have thanked those men enough.

The Canadian DamBusters. In the group photo we see 16 of the 17 surviving members of the Royal Canadian Air Force—15 Canadians and the legendary Joe McCarthy (second from right at back), an American in the RCAF. Standing, left to right: Sgt. Steve Onancia, Bomb Aimer on F-Freddie; Sgt. Fred “Doc” Sutherland, Air Gunner on N-Nancy; Sgt. Harry O'Brien, Air Gunner on N-Nancy; FSgt. Ken Brown, Pilot on F-Freddie; FSgt. Harvey Weeks, Air Gunner on W-William; FSgt. John William “Jack” Thrasher, Bomb Aimer on H-Harry; P/O George A. Deering, Air Gunner on G-George; Sgt. W.G. Radcliffe, Flight Engineer on T-Tommy; FSgt. Donald A. MacLean, Navigator on T-Tommy; F/L Joseph C. McCarthy, Pilot on T-Tommy; and FSgt. Grant S. MacDonald, AF on F-Freddie. Kneeling: W/O Percy E. Pigeon, Wireless Operator on W-William; F/O Harlo T. Taerum, Navigator on G-George; F/O Danny R. “Revie” Walker, Navigator on L-Love; Sgt. Chester B. Gowrie, Wireless Operator on H-Harry; and F/O David Rodger, Air Gunner on T-Tommy. A 17th RCAF airman, P/O John Fraser was shot down at the Möhne Dam and parachuted to safety to become a POW. Later in the war, Taerum, Deering, Thrasher and Gowrie would all be killed on ops.

The group of 15 airmen at the bottom are the Canadians who were killed on the raids. Left to right, top row: WO2 James L. Arthur; WO2 Joseph G. Brady; Sgt. Charles Brennan; P/O Lewis J. Burpee; Sgt. Vernon W. Byers; Sgt. Alden Preston Cottam; F/O Kenneth Earnshaw; P/O John W. Fraser. Bottom row: Sgt. Francis A. Garbas; Sgt. Abram Garshowitz; F/O Harvey S. Glinz; F/O Vincent S. MacCausland; Sgt. James McDowell; F/O Robert A. Urquhart; and P/O Floyd A. Wile. Photos: Bomber Command Museum of Canada

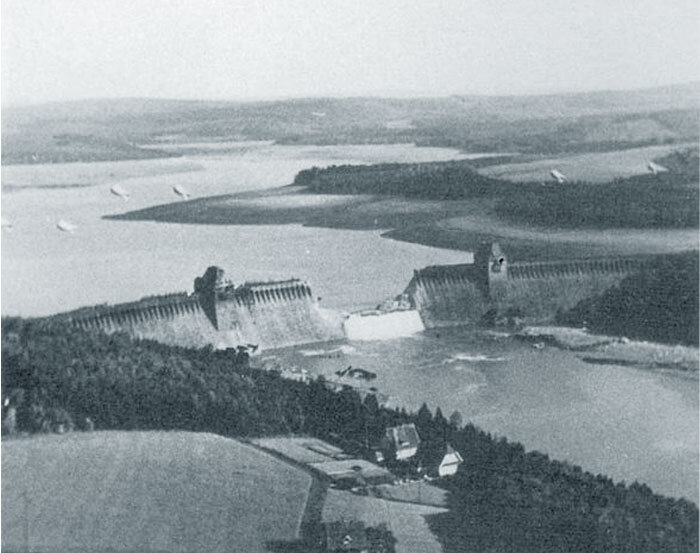

A photograph shortly after the Lancasters and their crews had breached the Möhne Dam, one of the headwaters of the Ruhr Valley. One can see that barrage balloons have been tethered in the approach path of attacking bombers, but by then it was too late. This breach was the most successful and most damaging of all the floods caused by the attack. The Möhne Reservoir, created by the dam, is an artificial lake in North Rhine–Westphalia, some 45 km east of Dortmund. The lake is formed by the damming of two rivers, Möhne and Heve, and with its four basins stores as much as 135 million cubic meters of water. The dam was built between 1908 and 1913 to help control floods, regulate water levels on the Ruhr River downstream, and generate hydro power. Today, the lake and the dam are also a tourist attraction, largely because of these raids. Photo: Bundesarchiv

Related Stories

Click on image

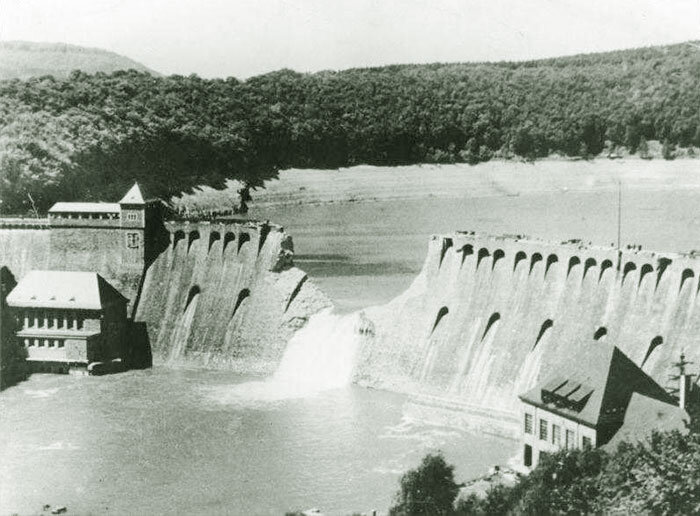

A view of the top of the Möhne Dam days after the reservoir has drained. The next photo gives you much the same view today. Photo: Bundesarchiv

The Möhne Dam today. Vintage Wingers Howard and Peta Cook visited the dam just a couple of months ago. The dam looks very much the same as it did on the night of 16–17 May 1943. Photo: Howard Cook

On the reservoir side of the dam, only a few metres of dam wall could be seen from the air, but the two blockhouses made perfect reference points from which to make a distance calculation. In order the work, the “skipping bomb” had to be released at exactly the right speed (240 mph), the right distance from the dam and at the right height (60 feet). 617 Squadron navigators came up with a simple hand-held targeting device with two prongs, making the same angle as the two towers at the correct distance from the dam, which showed when to release the bomb. (The BBC documentary Dambusters Declassified (2010) stated that the pronged device was in fact not used due to issues related to vibration and that other methods were employed, including a length of string tied in a loop and pulled back centrally to a fixed point in the manner of a catapult.) The second problem was determining the aircraft's altitude, as the barometric altimeters then in use lacked sufficient accuracy. Two spotlights were mounted, one under the aircraft's nose and the other under the fuselage, so that at the correct height their light beams would converge on the surface of the water. The crews practiced at similar dams and reservoirs in the north of England. Photo: Howard Cook

A scene from the Dam Busters movie of a 617 Squadron Bomb Aimer lining up the towers on the Möhne Dam with the spikes at the end of the “Y” of his simple wooden device.

Howard and Peta Cook posing on the river side of the Möhne Dam. One gets a true sense of the mass of the dam and the difficulties one would have breaching it with a bomb dropped from a 240 mph Lancaster. Photo: Howard Cook

A shot of the cylindrical “bouncing bomb” code-named “Upkeep”and its attachment system. We can see the chain drive that spun up the bomb to 400 rpm, a necessity to have the bomb skip and not breakup. Photo: RAF

The Möhne Dam the morning after the breach, with the reservoir still in full spill and roaring down the valley to the Ruhr industrial region. The two direct mine hits on the Möhne Dam resulted in a breach around 250 feet (76 metres) wide and 292 feet (89 metres) deep. The destroyed dam poured around 330 million tons of water, equivalent to a cube measuring 687 metres, into the western Ruhr region. A torrent of water around 32.5 feet (10 meters) high and travelling at around 15 mph (24 km/h) swept through the valleys of the Möhne and Ruhr rivers. A few mines were flooded; 11 small factories and 92 houses were destroyed and 114 factories and 971 houses were damaged. The floods washed away about 25 roads, railways and bridges as the flood waters spread for around 50 miles (80 km) from the source. Estimates show that before 15 May 1943 water production on the Ruhr was 1 million tonnes; this dropped to a quarter of that level after the raid. Photo: Bundesarchiv

From the top of Möhne Dam, we see the extent of the fine work of 617 Squadron. Photo: Bundesarchiv

The massive breach in the Möhne Dam and the exposed bottom of the reservoir evident to the right. Photo: Bundesarchiv

The damage done downstream wiped out much of the industry, but only for a relatively short period of time. The flooding caused more than 1,650 deaths, most of which were forced labourers from the Soviet Union. Photo: Bundesarchiv

A similar breach in the Eder Dam. Note the level of the water and the exposed shoreline behind the dam. Photo: Bundesarchiv

The Eder Dam from high above. Note the exposed flanks of the reservoir.

Some came home safely. Here the crew of 617 Lancaster T for Tommy, commanded by the famous American in the RCAF Big Joe McCarthy, pose after their Operation Chastise ordeal in a rare colour photo. During his attack on the Sorpe Dam, which required flying parallel to the dam, McCarthy made 9 attempts before dropping his bomb... a testament to his courage and determination. Joe McCarthy went on to a postwar career with the RCAF. He was the Chief Flying Instructor at Penhold when our own Tim Timmins did his Harvard course there. The crew included three members of the RCAF, two Canadian and one American. The crew of Lancaster ED825/“AJ-T” sitting on the grass, posed under stormy clouds. Left to right: Sergeant G. Johnson, bomb aimer; Canadian Pilot Officer D.A. MacLean, navigator; Flight Lieutenant J.C. McCarthy, pilot; Sergeant L. Eaton, wireless operator. In the rear are Sergeant R. Batson, front gunner; and Canadian Sergeant W.G. Radcliffe, flight engineer at RAF Scampton, 22 July 1943. Photo: RAF

The visit of HM King George VI to No. 617 Squadron (The Dambusters), Royal Air Force, Scampton, Lincolnshire, on 27 May 1943 – The King has a word with Flight Lieutenant Les Munro from New Zealand. Wing Commander Guy Gibson is on the right and Air Vice Marshal Ralph Cochrane, Commander of No. 5 Group is behind Flight Lieutenant Munro and to the right. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The visit of HM King George VI to No. 617 Squadron (The Dambusters), Royal Air Force, Scampton, Lincolnshire, on 27 May 1943 – The King has a word with Flight Lieutenant Les Munro from New Zealand. Wing Commander Guy Gibson is on the right and Air Vice Marshal Ralph Cochrane, Commander of No. 5 Group is behind Flight Lieutenant Munro and to the right. Photo: Imperial War Museum