GUNFIGHT OVER WESTMINSTER

While every Canadian airman and airwoman who participated in the Second World War can be proud of his or her service and their extraordinary contributions to the effort, there are very few who could say they were actively engaged in the war and its sufferings from the day it was declared to the day hostilities ceased in the European Theatre of Operations. Ottawa-born Alfred Keith Skeets Ogilvie was one of those who could.

Skeets Ogilvie, always an adventurous heart, longed to fly most of his early life. After being rejected by the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1939 because he lacked a university degree (that requirement would soon change), Ogilvie walked across the street to the RAF recruitment office, was accepted, passed his medical and was on a boat within a week! Ogilvie was just at the beginning of his flight training when war broke out in September of 1939. He fought through the bloodiest months of the Battle of Britain with 609 West Riding Squadron, took the war to the enemy the following year and was shot down, severely wounded and captured. Following many months of hospitalization, he was sent to Stalag Luft III, where he took part in the planning and preparations for the Great Escape. Skeets was the last man to make it out of the tunnel known as “Harry” before it was discovered.

Ogilvie was captured two days later and was lucky to be one of only a third of the escapees who were not murdered by the SS. Skeets survived four years imprisonment and the terrors and appalling conditions of the infamous “Long March” west and away from the advancing Red Army.

The Spitfire Luck of Skeets Ogilvie, a superb new book about the charismatic and legendary Canadian fighter pilot, has recently been completed by his son Keith Ogilvie and will soon be available in soft cover. Author Ogilvie weaves together the early years of his father and his mother, Irene Lockwood, as their pre-war and wartime lives come together during wartime. It is a story told from a distance and not by a son, but it is done with much love and admiration for the accomplishments of both Irene and Skeets. The book is salted with excerpts from the young fighter pilot’s logbooks, diaries, letters home and to his future wife, all warmly and richly connected by the author’s words.

Keith “Skeets” Ogilvie grew up just four blocks from where I write this introduction. He went to the same schools as my children and roamed the same rail yards as I did when I was a kid. As such I have always been drawn by his personal story as much as I have been by the famous and magnetic photograph of him taken by Sir Cecil Beaton or the wistful charcoal sketch of him done by Cuthbert Orde. He had the face of a direct, playful and tough customer, one who would become a Royal Canadian Air Force legend for not only his exploits in wartime or for his leadership role in the postwar RCAF, but for his irrepressible spirit.

In this shot by the legendary portrait photographer Cecil Beaton, taken at RAF Biggin Hill in April of 1941, Keith Ogilvie’s charisma, good looks and feisty nature are evident. Skeets was one of the few RAF aircrew who were both photographed by Beaton and sketched by Cuthbert Orde. 609 Squadron pilots all had their surnames printed vertically up the right side of their Mae Wests. Photo: Imperial War Museum

A 609 Squadron Spitfire Mk II from around the time of the squadron’s deployment to RAF Middle Wallop in the summer of 1940. Photo: RAF

The publisher of Spitfire Luck, Heritage House Publishers, has allowed us to select a short vignette from the book for publication on Vintage News. I have selected one particular story from the many, one that truly encapsulates his part in the Battle of Britain as a Spitfire pilot with 609 Squadron, Royal Air Force. The date is 15 September 1940… the day we now celebrate as Battle of Britain Day. It was a day marked by the largest participation of German and British aircraft during that epic and turning point battle—nearly 1,500 aircraft in all.

It was the high-water mark of the most celebrated aerial battle of all time. Front and centre on stage that day was one particular, concerted, angry and repeated mauling of a Luftwaffe bomber over Westminster in Central London. As necks craned to watch from the street far below, a single Dornier Do 17 Z was cut from the formation of Luftwaffe bombers and attacked repeatedly by a number of British fighter aircraft. One of those aircraft, a Supermarine Spitfire, was flown by Ogilvie who made several attacks on the hated raider, in the end emptying his entire load of machine gun ammunition at it. By the time Skeets and others were done, the crew members who were still alive had bailed out and the Dornier continued on autopilot. At this point, one last attacker, Sergeant Ray Holmes, made a final attack at the empty bomber and, finding himself out of ammunition, rammed the Dornier, slicing its tail off.

Related Stories

Click on image

Famed wartime portrait artist Cuthbert Orde made sketches of many Battle of Britain pilots at the request of the RAF. Though Skeets Ogilvie was a Battle of Britain veteran and ace, his portrait was not done until Orde was sent to 609 Squadron at Biggin Hill the following year, where he did portraits on many of 609’s pilots. Drawing by Cuthbert Orde

The following day, the entire country was reading the story of Ogilvie, Holmes and the others, drawn by riveting photographs of the dying German bomber falling from the sky. In these grainy and terrible images, Britons found an image that spoke to them and gave them hope that the Nazis, who had sowed the wind, would now reap the whirlwind. For some, those images were the first visual symbols of the end that would come 55 long months later. So here now are the Chapters 7 and 8 of The Spitfire Luck of Skeets Ogilvie. Enjoy.

Dave O’Malley, Editor—Vintage News

The Spitfire Luck of Skeets Ogilvie

Chapter 7—Battle of Britain Day

The next day, Sunday 15th weather was ideal for massed Luftwaffe attacks. Both (Air Vice Marshall Keith) Park and Prime Minister Churchill anticipated something significant and settled into the 11 Group headquarters Operations Room, located in a bunker at Hillingdon House on London’s west side, not far from the RAF headquarters proper. Churchill watched the subsequent action with an unlit cigar in his teeth, in deference to the limitations of the bunker’s ventilation system.

The date of September 15th is now commemorated as Battle of Britain Day. On this day in 1940, No. 609 Squadron—scrambled to meet the departing bombers—was the lone Squadron from 10 Group to participate in the massive dogfight over London late that morning.

Diary entry Sept 15/40 [Ogilvie’s book is rich with excerpts from his father’s diaries, logbooks and correspondences—Ed.]

Over London again and the Jerries are really throwing everything in now. We were ordered to intercept a heavy bomber formation headed for Northolt. “Butch” MacArthur identified them as Dornier Do 17s and then led us in on a head on attack. The 17’s turned out to have an armoured shield of ME 110’s in front as a spear head. Armed with four cannon, the ME’s poured out some stuff and we broke down and away. The plane beside me took a direct hit and went down a flamer. It turned out to be my room-mate, Geoff Gaunt. I came back up and saw several dogfights going on around and about. I was looking for an opening when five ‘vics’ of three 109s went over directly on top of me tailing the bombers. Damn good thing for me that they didn’t come down. I saw a Dornier Do 17 diving below and alone. A break for me, and I attacked him from the beam. The rear gunner fired back but packed up on my second attack. The third time I got in close and saw pieces coming off the enemy plane as well as a fire in his ‘glass house’, just as two of the crew baled out, one narrowly missing going into my prop. It was an incredible and terrifying sight to see the bomber spin slowly, suddenly the tail snapped off and then the wings and the wreckage plunged into the heart of London. I learned later that it landed on a jeweller’s shop by Victoria Station.

Skeets summarized that morning’s experience in a letter home, written shortly afterwards. He called the disintegration of the aircraft under his guns “a most amazing and terrifying sight. I could see fire in the Dornier’s cockpit.”

A formation of Dornier Do 17 Z medium bombers make their way towards England in 1940. The Dornier Do 17 Z, sometimes referred to as the Fliegender Bleistift or “Flying Pencil”, was, along with the Heinkel 111, one of the main bomber types arrayed against England during the Battle of Britain and the London Blitz. On the day we now know as Battle of Britain Day, Skeets Ogilvie and his 609 Squadron pilots would tear into a formation of the type from the Luftwaffe’s Kampfgeschwader KG 76. Photo: Bundesarchiv

A digital rendering of Oberleutnant Robert Zehbe’s Dornier Do 17 Z (F1+FH) of KG 76, based at Beauvais-Tille, France.Image via Asisbiz.com

Blurry and ghostly screen captures of gun camera footage from Skeets Ogilvie’s Spitfire on 15 September 1940 shows the Dornier Do 17 Z piloted by Luftwaffe Oberleutnant Robert Zehbe manoeuvering wildly and trying desperately to avoid being hit. The entire gun film from Ogilvie’s Spitfire lasts about 18 seconds. Since the gun cameras are activated only when the firing button is pressed by the pilot, Ogilvie fired absolutely all of the ammo he had available (350 rounds per gun at 1200 rounds per minute). To watch Ogilvie’s attack on Zehbe’s Dornier, you can watch it on the Imperial War Museum’s archival website. Go to: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1060013903. Ogilvie’s footage starts around the 12:30 minute mark. Images via Imperial War Museum

In the last two seconds of the Ogilvie “cine-gun” footage, a large chunk (or possibly the pilot Zehbe) comes spinning off the port side of the Dornier and tumbles past Skeets’ Spitfire. Image via Imperial War Museum

The pilot of the Dornier, Oberleutnant Robert Zehbe and two crew members were killed [Zehbe died the next day from wounds after bailing out and being roughed up by Londoners—Ed]. The two German parachutists landed on the Kennington Oval, according to Ziegler “fortunately without disturbing any cricket, whereas the main part of their aeroplane arrived in the forecourt of Victoria Station, and the tail-unit (as is recorded in the Squadron’s war diary) ‘just outside a Pimlico public house, to the great comfort and joy of the patrons.’ ” The bulk of the wreckage demolished a jeweller’s shop and damaged the Victoria Station restaurant, where 30 women were taking shelter in a basement room. Trapped by the wreckage, they had to be freed, uninjured, by a party of men who broke in through a locked door at the other end of the room. They came out with their knitting and raised a cheer for the RAF. They were most worried about the state of their lunch. One was quoted as saying, “after we had taken a look at Jerry, we tidied up the mess he had made.” That pretty much says all that needs to be said about the attitude of Londoners for the duration of the war.

Other newspaper articles describe this most public dogfight of the war, with Londoners standing in the streets during the lunch hour and cheering wildly as they watched the flaming enemy aircraft fall to the ground. The whole episode was photographed and recorded in the London Daily Mirror, who presented original copies of the photographs to Ogilvie. One shows the Dornier falling on and near Victoria Station, at the corner of Wilton Road and Terminus Place, with the tail and wing tips missing, with an unidentified fighter in the bottom of the picture. Another shows the tail section falling separately to land on a rooftop in Vauxhall Bridge Road, while others show the wreckage being checked by rescue personnel.

What’s left of Zehbe’s Dornier falls from the sky toward Victoria Station while hundreds watch from the streets below. Because of concerted attacks by Ogilvie and others, Zehbe’s observer Hans Goschenhofer and gunner Gustaf Hubel had been killed and the aircraft was abandoned by Zehbe and the remaining members of his crew. The Dornier, now flying on autopilot across Central London, was spotted and attacked by Sergeant Ray Holmes of 504 Squadron who, out of ammunition, rammed the empty Dornier slicing off its tail. Subsequently, the spinning wreck shed its outer wing panels and dove to the forecourt of Victoria Station. In the photo at left, we can see what is likely Holmes’ Hurricane in the lower right. Holmes seriously damaged his aircraft and was himself forced to bail out over London. Photos via Author Keith Ogilvie

The front page of The Daily Telegraph for the following day, September 16, 1940, depicts the damage at Victoria Station. If you read the other headlines on the front page of this paper, you would think that Britain had the Axis on the ropes, which of course, was far from the truth. Image via The Telegraph

London firefighters work to put out the fire at Victoria Station (at left). The Dornier seriously damaged shops such as James Walker, a jewelry and gift shop along Wilton Road. Photo: Stephen Hunnisett blitzwalkers.co.uk

The proof of his contribution was in the 16 mm camera guns that were synchronized with the Spitfire’s eight .303 calibre machine guns. They clearly show pieces of the airplane flying off and crew members baling out, as the Dornier is caught squarely by a lethal blast before falling to earth in pieces. Ogilvie noted in his combat report that two other Spitfires had also attacked the Dornier.

Chapter 8—A Royal Note

The bomber was thought to have tried to bomb Buckingham Palace, but Skeets thought it more likely the pilot was simply jettisoning his bombs and trying to get away. Whatever the case, the bombs caused minimal damage when they fell in the courtyard of Buckingham Palace, where Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands was standing on a balcony watching the air battle. The Dutch royal family were staying at Buckingham Palace for the duration of the war and, along with other Londoners, were following the action from the ground. Queen Wilhelmina put her gratitude for the aerial action they had witnessed into concrete terms in the form of a personal note to Skeets which is now in his diary. It reads as follows:

Dienst Van H.M. de Koningin,

Der Nederland

82, Eaton Square

London S.W.I.17 September, 1940

I am commanded by her Majesty Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, to convey to you Her Majesty was most gratified to see from her London House a German bomber shot down by an eight gun fighter during the air battle in the morning of 15th September.

Her Majesty would be very pleased if Her congratulations should be conveyed to the Squadron concerned in this battle and to the pilot who shot down the German aircraft.

(Signed Major General de Jonge Van Ellemeet

Aide de Camp on service.

To : --The Air Ministry, London

The note was forwarded to 609 Squadron from Fighter Command, along with another ordering that no publicity should be given to it.

The writeup in the latter pages of Skeets’ Flying School diary contains a more businesslike and detailed report on the day’s action.

Combat Report Sept. 15/40

I was Yellow 2, in “A” flight. We were ordered to attack heavy bomber formation headed for Northolt. A head on attack was a failure, came up on one side, saw many 109’s pass over me tailing the bombers. Saw lone Dornier 215 and made beam attack, experiencing return fire. One grazed tailplane. Another Spitfire joined in, on second attack pieces came off and could see a fire in glass house. Crew jumped and bomber went into spin, broke in half and crashed over Battersea, London.

However, the account of the day’s action was not without controversy, as was the case with many of these events. Ogilvie always acknowledged that there were probably several people who could have shared responsibility for this “kill”. In addition to the other Spitfires Skeets acknowledged were part of the attack, Sergeant Pilot Ray Holmes of 504 Squadron claimed he was out of ammunition and had actually rammed the Dornier, then baled out of his Hurricane over Chelsea. Richard Collier, in his book “The Few”, credits Sgt. Pilot Ginger Lacey with downing a Heinkel that was supposed to be “the only bomber that dropped bombs on Buckingham Palace”… so there is naturally great confusion about all this. In 2004, some of the wreckage of Holmes’ Hurricane was dug up during a street rebuilding exercise in downtown London, and was put on display at Leicester Square as part of the “West End at War” exhibit, then subsequently preserved at the RAF Museum.

Ian Darling, a Canadian journalist and author wrote, a book[1] that in one chapter recounts Skeets’ experience on September 15th. Darling’s research included examination of camera gun footage taken from Ogilvie’s aircraft. In a letter to the Ogilvie family, he wrote,

“…the film from (Skeets’) Spitfire at the Imperial War Museum…shows several scenes when (he) was attacking the Dornier. It also shows what appears to be the tail of the bomber breaking away.[2] This scene is intriguing because (he) is in front of the Dornier. Interestingly, the film of the tail leaving the plane starts with the tail in the air, having left the plane. Just what occurred in the seconds before (he) switched the camera on is something that will never be known with absolute certainty.”

Darling goes on to say that he believed (Skeets) was “both accurate and modest when he wrote…that several pilots were involved in the attack. I spoke to the staff at the museum about the film and they confirmed that there is no way to be absolutely certain what occurred during that couple of seconds before the bomber started to break up.” Then he brings the incident into the present.

“You may also be interested to know that the Dornier scraped against the granite at the base of Victoria Station when it crashed and that the scuff marks remain there to this day. I went to the customer service department at the station, introduced myself and asked to speak to anyone who knew about the Dornier coming down at the station. I met a person who is like a promotion manager and he took me to where the Dornier ended up. He showed me how rough the granite is in one area and how smooth it is about 30 feet away… The part of the station where the plane came down is now a pub (The Iron Duke), so it is easy to find.

With the crash site secured, police and military inspect the wreckage of the aircraft and James Walker’s Jewelry shop. Photo: telegraph.co.uk

Military and police officers inspect the wreckage of Zehbe’s Dornier after the fire was put out. In the bottom right, dozens of mantle clocks lay scattered across the sidewalk along Wilton Road. Photo: dailymail.co.uk

Today, the shops in the forecourt of Victoria station along Wilton Road have gone, but the patio outside The Iron Duke Pub marks the exact spot where the Dornier impacted. Photo via Google Maps

The empennage from Zehbe’s Dornier came to rest a few hundred metres away on a rooftop along Vauxhall Bridge Road. Here, soldiers inspect the damage and the remains of the aircraft. Photo via aircrewremembrancesocety.co.uk

A British Soldier stands guard over the port vertical stabilizer of Zehbe’s Dornier on a rooftop along Vauxhall Bridge Road.

At the time of the action, however, the uncertainty about just how much credit Skeets deserved for this victory was hardly an issue. After rearming and refuelling, 609 Squadron was again ordered into action around 14:30 that same afternoon, just after the enemy crossed the Kentish coast, and arrived at the action only in time to intercept the bombers from the Brooklands–Kenley patrol line as they returned from their mission. Skeets’ diary resumes.

In the afternoon, we intercepted some 20 Dorniers tearing for home off Hastings. We were too late for the main body but there were two stragglers and my flight took one each. On our “kite” my attack was the third and it was starting to go down, though the rear gunner was still firing and hit my wing. The bomber just came to pieces and two of the crew jumped. On “B” flight’s attack, Mike Appleby was leading but the boys were so excited they peeled off from the rear first, and when Mike started to go down, he found himself last in line. He was some burned up. This one crashed on the beach.

I followed a parachutist down to the sea and took some film of his descent. He waved quite wildly, probably figuring that he was going to be machine gunned. He landed about ten miles out and I doubt if he was picked up at all as there was nothing in sight.

The squadron was credited with four destroyed, four probables and several damaged, bringing our score up to 66 destroyed. The total for the day was officially reckoned at 185 Jerries definitely downed.

Unfortunately we learned that Geoff [Gaunt, Skeets’ roommate] went straight in (at) Kenley for our only casualty.

Skeets never again mentions a roommate in his diary. Most poignantly, Gaunt must have intended to keep a diary himself but never started it. It fell to Ogilvie to do so, and his personal record was borrowed as a reference by Frank Ziegler when the latter was writing the 609 Squadron History. Ziegler describes the provenance of the actual notebook thus:

“I have before me as I write two ‘RAF Large Note Books, Form 407’. One bears the name ‘S.G. Beaumont’. On the cover of the other the name ‘G.M. Gaunt’ has been deleted and that of ‘A.K. Ogilvie’ substituted. It is recorded that at Middle Wallop they shared a room, and it is clear that Gaunt never had a chance even to begin his diary. But Ogilvie did, and when he was posted missing in 1941 it was forwarded to an address in Ottawa written on the fly-leaf. Thirty years later it has been sent to me by its Canadian owner—who after all survived.”[3]

Skeets later summarized the nature of friendship in these perilous times.

“…people came and went, you know. You’d lose some. You’d get to know a guy pretty well, then all of a sudden he wasn’t there any more. You just sort of got used to it. We had some guys who came to the squadron, and went missing on their first trip. You just didn’t know—if your luck ran out, it ran out.”[4]

The date of September 15th had seen the arrival over England of the largest aerial armada the Luftwaffe was able to muster; it also led to the RAF’s most exaggerated claim of victories in the whole of the Battle of Britain, 185 enemy aircraft. The Squadron’s claim of four aircraft destroyed was accurate, but the final tally for the RAF as a whole was 56. There is no doubt many of the returning German aircraft suffered damage.

In any case, it was a near thing for the RAF. Fighter crews, barely down from the morning’s intensive action, were faced with over twice as many aircraft in the afternoon. Fighter Command was stretched to the limit. A famous anecdote records Churchill turning to Park in the 11 Group Operations bunker as the plotting table once again filled with markers and lights showing engagement of Fighter Command’s pilots, and asking, “What reserves have we got?”

“There are none,” was Park’s answer. But by early evening, when Churchill and Park left the bunker, the sky was clear, calm and empty of aircraft.

Skeets’ log book credits him with a “D.O.215 destroyed”. The Squadron’s record of victories shares the kill with PO J. Curchin, but also notes:

“Claimed by numerous RAF fighters and crashed at Victoria Station.”[5] It was a famously public victory, brought to all Londoners with the publication on the front pages of many of the London papers of the pictures of the doomed aircraft, tail-less and without wing tips, plummeting vertically to the ground. The incident came to characterize for many Londoners what Winston Churchill later described as “one of the great days…the most brilliant and fruitful of any fought upon a large scale by the fighters of the Royal Air Force.”

The amputated hulk of Zehbe’s Dornier plummets like a dying falcon toward the forecourt of Victoria Station, followed by the eyes of London’s citizens. Photo: saak.nl

Not long after, Skeets wrote to his younger brother Jim about the incident, but the letter is just as interesting for the broader perspective it puts on the experience of being in London on the ground during these raids. “I’m in London on leave,” Skeets writes. “Eleven o’clock at night and a fine rest I’m getting. The sky is red from a fire Jerry has started somewhere and you can hear the bark of Archie[6] guns close by. The sky is criss-crossed with searchlights but the clouds are low and they can’t pick out anything. And at home you are probably cursing at the mosquitoes…”

A final footnote to this day took place some 50 years later, at an event commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Britain. Skeets was introduced to the Queen as the pilot who brought down the bomber that had bombed Buckingham Palace. The Queen thought for a moment, obviously remembering the incident. “It didn’t do any damage, you know,” she said, “as all the bombs landed in the forecourt.” There was probably more damage done when the aircraft fell on Victoria Station and the adjacent shops.

Following this hectic day, Skeets seemed to adopt a more fatalistic attitude to the daily events. He later said, “Things went on from there. If you were lucky, you came out on the right end of things. If you weren’t, well, you didn’t.” In any event, the following week was an anticlimax for Skeets and his fellow pilots.

Excerpted from The Spitfire Luck of Skeets Ogilvie—From the Battle of Britain to the Great Escape by Keith C. Ogilvie

Credit: The Spitfire Luck of Skeets Ogilvie: From the Battle of Britain to the Great Escape. © Keith C. Ogilvie, 2014. A first paperback edition of You Never Know Your Luck, published by Heritage House (heritagehouse.ca) by arrangement with Flying High Publishing. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

To order your copy of The Spitfire Luck of Skeets Ogilvie, click here.

Author Keith C. Ogilvie

Skeets with 609 Squadron—a photo essay

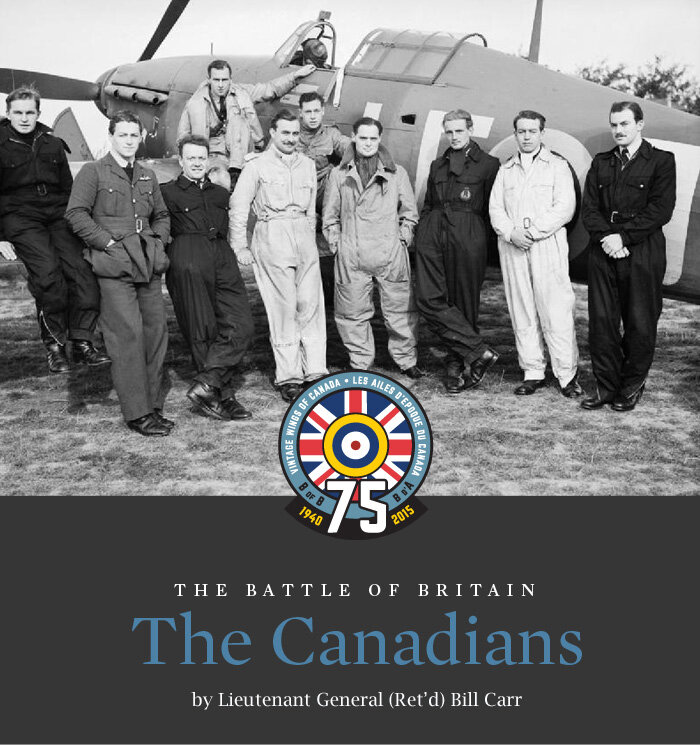

We searched the web and other sources for images of Skeets Ogilvie’s service during the Battle of Britain and on fighter operations the following year. While not a complete story by any means, it pays out one powerful thread—of squadron pride, the brotherhood of the fighter pilot, and the bond forged when one’s friends’ lives are in one’s own hands.

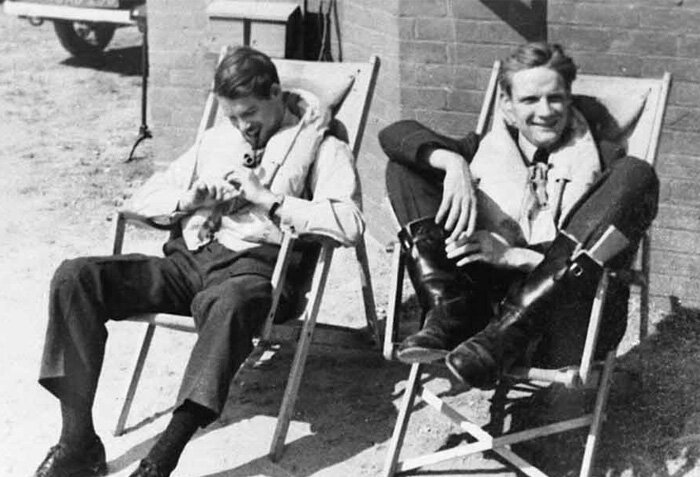

Two 609 Squadron pilots from the colonies. A pipe-smoking Pilot Officer Keith “Skeets” Ogilvie (left) and American Pilot Officer Eugene “Red” Tobin (note map stuffed in his boot top) sit in beach chairs, likely at RAF Middle Wallop in September of 1940 and look rather bemused by the photographer. Red Tobin would survive another year before being shot down and killed in September of 1941 while on a fighter sweep over France flying with an all-American unit—71 Squadron, RAF. Photo: AcesofWW2.com

In October of 1940, with the Battle of Britain winding down, 609 Squadron celebrated their 100th confirmed enemy aircraft shot down. They cut the swastika from the tail of the Ju 88 in question and painted a tribute panel for their mess at RAF Northolt. Here, the pilots of the squadron pose with the panel while sitting on one of their Spitfires, with Skeets sitting right next to the propeller blade at the top right. The panel reads: “Salved from Ju 88. The 100th enemy aircraft shot down by 609 Squadron, 21st October 1940. F/Lt. Howell, D.F.C. and P/O S. J. Hill” Photo: 609 Squadron Association

A great shot of pilots of 609 Squadron in conference—likely at Middle Wallop. A mustachioed Skeets Ogilvie peers toward us at centre. The photo did not come with a caption, but the man with his back to us looks to be Squadron Leader Mike Robinson, while the blonde-haired pilot is most certainly Flying Officer Frank Howell. Second from left is Flying Officer John “Dogs” Dundas. The others, I am still attempting to identify. Robinson was killed in April 1942 during a fighter sweep, while Dundas was killed in November of 1940 near the Isle of Man, not long after this photo was taken. Howell was killed after the war in 1948. He was filming his Vampire pilots of 54 Squadron, when he was struck in the head by the wing of one jet. Flying fighters was indeed a dangerous business. It is interesting to note that, in those days, pilots flew combat missions in shirt, tie and tunics. Photo: 609 Squadron Association

According to the 609 Squadron Association website, this photograph was taken at RAF Biggin Hill. Since Skeets only spent one operational winter with the RAF, and was shot down in July of 1941, this is likely a photograph taken around the time of the Squadron’s arrival at Biggin Hill in February of 1941 (judging by the heavy clothing and bare trees). Skeets is fourth from left in casual Canadian style with hands in pockets, wide toothy smile, open flight jacket and silk scarf. Photo: 609 Squadron Association

A photograph taken in the dispersal at RAF Biggin Hill in the spring of 1941 shows 609 Squadron pilots at the ready and warming themselves in the weak rays of the sun. Skeets sits in front, intent on cleaning something with a rag. Left to right standing behind him are John Curchin and Willi Van Lierde. Sitting in rattan chairs to his left are Ferdinand Baraldi, Francois Xavier de Spirlet and then Victor “Vicky” Ortmans. Flight Lieutenant John Curchin, DFC would die a few weeks later when his Spitfire collided with a Messerschmitt Bf 109 near Dover. Pilot Officer Willi Van Lierde, one of many Belgians on squadron, was posted to 609 on 7 April 1940 as was de Spirlet, dating this photograph after that time and before Curchin’s death (an 8-week window). After his 609 service, Van Lierde became a flying instructor and survived the war. Pilot Officer Ferdinand Henry Raphael Baraldi, who remained with the squadron when it moved on to North Africa, survived the war as a Squadron Leader. Ortmans also survived the war but was killed while demonstrating an Auster light airplane in 1950 while in the service of Sabena Airlines. De Spirlet was killed at RAF Duxford a year after this shot was taken. While taking off in formation, the left main tire of his Typhoon burst and his aircraft careened across the runway hitting another 609 Typhoon. He was killed, but the other pilot was uninjured. Photo: 609 Squadron Association

609 Squadron pilots do what all pilots have done since the beginning of combat flight—describe the action with their hands. Skeets is at left with his sunglasses on, while his friend John Bisdee is hidden to his left in this after-action photograph taken at Biggin Hill sometime after their arrival in February. The Belgian Bob Wilmet looks on from the right with Mike Robinson listening with hands in pockets. Photo: 609 Squadron Association

Another 609 Squadron pilots photo taken at Biggin Hill, the occasion unknown. Skeets Ogilvie is standing casually, fifth from the right, with his broad white smile beaming like a beacon. The warmer clothing indicates the first few months of their stay at Biggin Hill, which started in late February. Photo: 609 Squadron Association

This photograph appears on the 602 West Riding Squadron Association website and shows Skeets with “Bish” Bisdee and two other pilots, all rather formally dressed, pressed and relaxing in a garden. At least three of the men have DFC ribbons, which leads one to suppose this was on the actual occasion of the award of their Distinguished Flying Crosses. Both Bisdee and Ogilvie were awarded theirs on the same day—11 July 1941. Bisdee, once called “a cheerful blonde mountain of confidence” was a close friend of Ogilvie who was similar in spirit. Photo: 609 Squadron Association

Scouring the 609 Squadron website for images of Keith Ogilvie, all were uncaptioned. But like most images, certain things can be deduced. Skeets is seen here at left with his usual uber-relaxed smiling Canuck vibe, open coat, cap pushed back and hands deep in pockets. The heavy clothes lead one to think of late winter—perhaps March or April of 1941. It’s the men next to him that draw your attention however, as both are in civilian clothes. One of them, the smirking fellow with the dark hair is the American RAF pilot legend Flight Lieutenant Andrew “Andy” Beck Mamedoff. Mamedoff had been posted to 609 Squadron during the height of the Battle of Britain, but had left in mid-September of 1940 to help found 71 Eagle Squadron along with Red Tobin at RAF Kirton. It’s possible that this was a simple social visit to 609 to catch up with old friends. The following October, the 29-year-old Mamedoff was killed while ferrying a Hurricane in inclement weather from RAF Fowlmere to RAF Eglinton, Northern Ireland. Photo: 609 Squadron Association

A great but damaged shot of Skeets sitting on the wing root of a 609 Squadron Spitfire at Biggin Hill. This was Supermarine Spitfire Mk IIa (P8381) Stroud, a presentation Spitfire from the people of “Stroud and District”, a market town on Gloucestershire, England. This helps us date this photograph, as the “Stroud” Spitfire arrived new at Biggin Hill and with 609, direct from the maintenance unit that accepted it from the factory. A presentation aircraft like the Spitfire was a war fundraising vehicle and there were hundreds such aircraft in the RAF. A company, group or community could raise money (about 5,000 £ for a single-engine fighter) and have their name written on the side. Usually, squadron pilots would pose with it and the RAF would have prints sent to the donors. It’s possible that was the purpose of this shot. The Stroud Spitfire was delivered to 609 on 5 May 1941. This aircraft was then sent on to 452 RAAF squadron on 20 June, so we can date the photo to that 6-week period. Given the gloves and warm clothing, it’s likely early in May. Photo: 609 Squadron Association

A gorgeous photograph of a 609 Squadron Spitfire V taxiing at sunset at RAF Biggin Hill. Photo: 609 Squadron Association

On the 28th of June 1941, a newspaper photographer visited Biggin Hill and 609 Squadron and took a series of rather playful images—the pilots playing cricket, clowning with a hay wagon and chumming with the squadron mascots. Here we see a staged game of cricket (though the batter appears to be swinging more of a baseball bat). Skeets Ogilvie can be seen squatting at right and laughing. Photo: 609 Squadron Association

A quirky public relations photograph dated June of 1941 shows Spitfire fighter pilots of 609 Squadron, all with their “Mae Wests” on, pitching in to help with the farm harvest on the grounds of RAF Biggin Hill. A staged photograph if there ever was one. Pilot Officer Keith “Skeets” Ogilvie is in the middle with his tunic on under his Mae West—not exactly proper farm work wear. To the left is John Derek “Bish” Bisdee, so identifiable with his mop of thick blonde hair, while at the right is Belgian Pilot Officer Baudouin Marie Ghislain de Hemptinne of Ghent, Belgium. Standing on the hay truck are (l to r) Sergeant Bob Boyd, Pilot Officer Peter MacKenzie and Tommy C. Rigler. With the rake at left stands another Belgian, Pilot Officer Victor “Vicki” Ortmans. Photo: Evening Standard, collection of A.K. Ogilvie

Another wonderful Public Relations shot taken on that day in June 1941 at RAF Biggin Hill shows a group of pilots with a Spitfire and three of their squadron mascots—a puppy, a dog and the newly arrived “William (Billy) de Goat” who would become the chief and legendary mascot of the squadron. Historian Martin Waligorski, in The Amazing Career of Officer Billy de Goat (Spitfiresite.com), writes: “In February 1941 the squadron was relocated to Biggin Hill. It was there that Billy de Goat was recruited to the unit. He was a kid given to one of the Belgian pilots, Vicki Ortmans by the landlady of Old Jail, the local pub in Biggin Hill (which still exists today). Christened William de Goat, he would remain with the squadron for four years, through all its various postings, firstly in the UK, then into France, the Low Countries, and finally into Germany and the victory in Europe. During that time, he patiently tolerated all Squadron members and their foibles, watched the new pilots come and go, spent long evenings at the bar with them, was cared for and spoiled, exercised his great appetite for Things Eatable and generally became essential to everyone’s morale.” Skeets sits second from right in front with his arm around “Petie”, Sailor Malan’s dog (the legendary Malan was the Biggin Hill Wing Commander). The others in this shot are, left to right, standing: Sergeant Bob Boyd, Pilot Officer Baudouin de Hemptinne, Pilot Officer Peter MacKenzie, Flight Lieutenant Paul Richey, Flight Lieutenant John Bisdee, Pilot Officer Jean Offenberg and Flying Officer Jimmy Baraldi. Sitting: Pilot Officer Victor Ortmans, Sergeant Tommy Rigler (with a squadron dog named “Spitfire”), Skeets and finally Pilot Officer Bob Wilmet. Photo: 609 Squadron Association

Another close-in photograph of 609 pilots with Billy de Goat and other mascots at Biggin Hill. Left to right: Belgian Flying Officer Victor “Vicky” Ortmans, DFC, Flight Sergeant Tommy “Hair Wave” Rigler, DFC (eventually a Squadron Leader with a DFC) with “Spitfire”, Skeets Ogilvie with Sailor Malan’s dog “Petie” and the Belgian Robert “Bob” Wilmet. Ortmans was an ace who survived POW camp, but died in an airplane crash after the war. Rigler, a highly-decorated ace having shot down 8 Bf 109s, survived the war. Wilmet later transferred to 349, an all-Belgian Squadron forming up with Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks at RAF Ikeja, near Lagos, Nigeria. He died in unknown circumstances there in 1943. Photo: 609 Squadron Association

Skeets (left) hams it up for a Public Relations shot at RAF Middle Wallop in the summer of 1941 with Tommy Rigler and Sergeant Ken Laing (right). Laing, another Canadian, would be shot down the following November 1941 and like Skeets, spend the rest of his war in a POW Camp—Stalag VII. Photo: Collection of A.K. Ogilvie

Left: Pilot Officer Skeets Ogilvie in September 1940 around the time of the battle with the Dornier over London. He is standing in front of a Miles M.9A Master I, a British advanced trainer. Right: A photo of Flight Lieutenant Skeets Ogilvie, possibly heading home to Canada aboard Queen Elizabeth. He wears the stripes of a Flight Lieutenant, a rank he achieved while he was a prisoner of war. He wears his DFC and service ribbons and carries perhaps one of his diaries that told us so much of his time in the RAF. Photos: left: Collection of Keith Ogilvie; right: RCAF

Skeets Ogilvie joined the RCAF after the war and entered the jet age. Photo: Collection of Keith Ogilvie