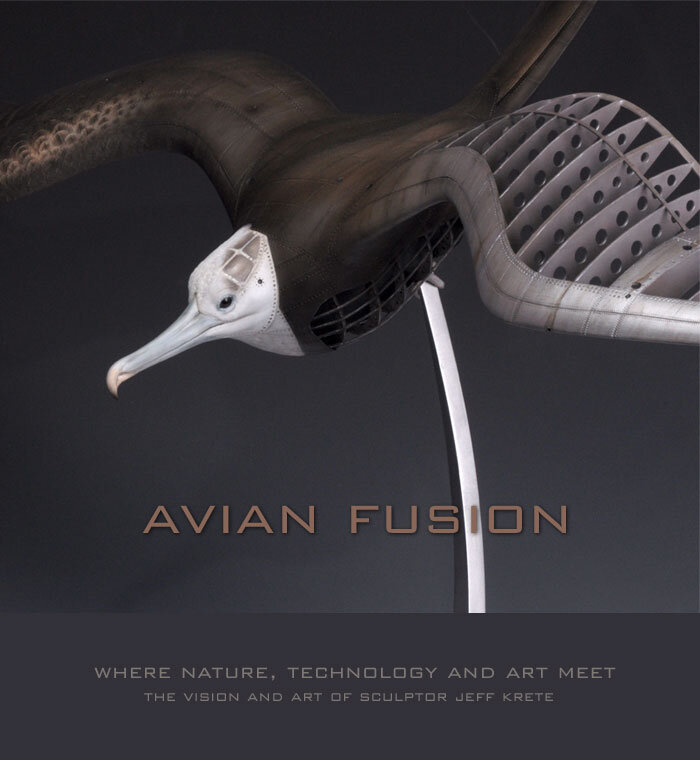

AVIAN FUSION — Where Nature, Technology and Art Meet.

While the discussion is still ongoing as to which came first—the chicken or the egg, it is certain that the bird was the source of inspiration behind the airplane. From Icarus to Otto Lilienthal to New Zealand’s Richard Pearce to Ohio’s Wright Brothers—man has long sought and found the ability to fly like a bird, and in particular the long-duration soaring birds of the oceans. While this is not a story of aviation history, the world of aviation is filled with passion, ideals, emotions and the longing for the freedom of flight. We cannot speak of aviation history without addressing the long-held desire in our souls to leap into the air and play upon the invisible waves like a bird. Artist Jeff Krete, a sculptor of both avian and aviation subjects, pays powerful artistic tribute to that passion in all of us and the short history of manned flight.

In 1959, when I was 8 years old, I was given a pair of Carl Wetzlar binoculars for Christmas by my parents. These binoculars were the greatest gift of my youth—solid, heavy, German-made, and optically precise. Grasping their pebbled grips in my young hands and training them on a distant subject, they enabled discovery in a whole new way. They opened up two linked, but different, worlds for me—the world of aircraft and the world of birds.

I was a lucky young fellow, for I lived just two miles from RCAF Station Rockcliffe, one of Canada’s oldest and most legendary military airfields, and four miles from RCAF Station Uplands, one of the biggest bases in the land. My parents’ home was brand new—standing far, far out on the very edge of the first stumbling attempts at suburbanization. Today, my old neighbourhood is considered “central”, but back then, it was far from it. We were surrounded on all sides by farms, farmers, fields, woodlots, streams, creeks, rail lines and dusty country roads. Today, Smyth Road is four lanes wide, but in the 1950s it was a gravel road, with shoulders sloping down to drainage ditches. Our small development was a peninsula of the future, reaching outward to take hold in farmland.

Summer after summer, I wandered the fields and roads with my “binos”, training them on hawks in flight, redwings mobbing a raven, a line of mourning doves on a country phone line or a late summer sky seamed with threads of Canada geese. But even more so than the birds, I was attracted to the aircraft that always seemed to be in the air around me—the thundering Lancasters and Harvards from Rockcliffe, the wailing CF-100s from RCAF Uplands and whistling Vickers Vanguards climbing out of Ottawa Airport. I was small, dirty, dishevelled and curious, lying on my back in Farmer Borthwick’s pasture, training my glasses on everything that flew.

At the beginning of this lifelong obsession, I thought I was alone in this avian curiosity. It wasn’t long, however, before I understood that nearly every kid in my neighbourhood was afflicted with this disease, this attraction to all winged things. These days, nearly 55 years later, my circle of friends and colleagues reads like a support group for aviation addicts. Among many of these are graphic designers, architects, artists, poets and musicians. Something about flight, its poetry, its drama, its tragedy and its visuality appears to attract the right-brained, the romantic and the communicative.

Being a professional graphic designer, I have many talented colleagues who can create avian magic with their Adobe Creative Suites and imaginations. Many more friends and acquaintances are superb aviation artists in every genre—airbrush, acrylics, water colours, oils and photography. Of these, one stands out beyond the rest for his combination of skill, talent, work ethic, high standards, imagination, passion for detail and accuracy. His name is Jeff Krete.

Krete has the ability to draw the breath right out of me when viewing his exquisite wood carvings of waterfowl and wildlife. His work gives us an impassioned look at nature’s spectacular detail and captures, in basswood and paint, a millisecond in time, a fleeting moment we would otherwise never see. Each sculpture has the effect of stopping you dead in your tracks, compelling you to look and to feel as though you are seeing for the first time. Unlike a photograph or a painting, we can walk around this captured piece of time and nature, providing the visceral feeling that we are witnessing time stood still.

Carving in the Avian World

Though Krete’s duck decoy projects are done at life size, he has won worldwide acclaim for avian sculptures known as miniatures. Here, three North American-native pintail ducks flash low over water in a piece called “Pintail Trio”—a World Championship-winning sculpture. In the tiny world of woodcarving miniatures, anatomical detail and accuracy are a must, but keeping true to the character of the species is a challenge indeed. While wings are constantly in motion and can be said to be accurate in any position, the head of the bird is where the judge’s attention will focus. It is here, in face of the lead pintail (a female), that we read the sleek determination and flashing speed of the species. The whole piece is just 20 inches high. Photos: The Ward Foundation

Related Stories

Click on image

Krete’s miniatures always include a base or context that illuminates the habitat of the species he is carving. In the case of the cattle egret, Krete decided to tackle the symbiotic relationship between the elegant white bird and the Cape buffalo. An avian purist at heart, this was Krete’s only mammalian sculpture to date, and it presented a powerful statement about animal behaviour and habitat. The piece measures 12 inches across at the horns—making the egret itself not much more than four inches in height. Krete worked with taxidermy experts to provide accurate photographs of all aspects of the head. The scaled glass eyes of the Cape buffalo were made for the piece by a glass eye specialist in the United States. Photo: Jeff Krete

Krete, a biologist with Ducks Unlimited, shares a deep concern with his entire organization for shrinking waterfowl habitat. To express this fear, Krete tackled a carving of a species that has not been seen on this earth since the 1930s—the pink-headed duck. Krete is passionate about his mission at Ducks Unlimited, stating “… The story of the pink-headed duck’s habitat loss (conversion of habitat to agricultural use) is similar to what has/is happening here in North America. This why we work at Ducks Unlimited to protect, secure and restore wetland habitat for our native waterfowl.” Finding research material (images, habitat and dimensions) for an extinct bird that is native to Borneo and Malaysia was a challenge. Krete’s spectacular success in international competition gave him the credentials to approach world-class museums like the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto and the American Museum of Natural History in New York for access to their extremely rare specimens (skins)—receiving measurements and photographs. Photo: Jeff Krete

A threesome of widgeon ducks (two males and a female) fly as one, banking hard and low across a wetland surface, eyes looking out ahead for open water upon which to light. One can almost hear the rapid whistling of their wings. Another challenging miniature, this piece took Krete to a whole new level in achieving anatomical perfection and describing the complexities of flight dynamics. Krete accomplishes a powerful sensation of flight by assembling the pieces and supporting them on the thin blades of wetland grass, made from steel rods. Photo: Jeff Krete

Hand-Carving History

A wildlife biologist, hunter, artist, and ex-member of Canada’s Armed Forces, Krete has recently applied his considerable talents with bird carving to the other realm of flight—the world of man-made aircraft. He recently began a ten-year project to sculpt, and then cast copies in bronze of some of the most storied fighter aircraft of all time. The work combines the soft hands-on feel of his basswood works with the time honoured traditions of a Japanese bronze foundry to express the same moment in time voyeurism of his natural pieces. The result is a monument you can hold in your hands—a monument to history, design and courage and a timeless piece worthy of private collections and passionate aviators around the globe.

The following photographs depict the complex process, the eons-old artistry of Japanese craftsmen and the end result of hundreds of hours of planning and execution. In a world of instant response, digital everything, online shopping carts, and mass-produced Chinese knockoffs, it is inspiring to witness an artist expend years of his life to capture a millisecond of time.

The artist in his studio, surrounded by inspiration in natural and man-made forms. The P-51 Mustang was Krete’s first work of an aviation, rather than an avian, subject. It was the first of a series of aircraft bronzes that will take Krete a decade to produce. It is a daunting task and one for which he had to relearn his craft: “Although I had carved a few aircraft pieces in the past and spent my youth modelling aircraft, nothing had really prepared me for the challenges of carving the Mustang bronze project.—The P-51 Mustang was a man-made object assembled in a jig to be perfectly symmetrical and I was used to carving organic pieces, not necessarily with perfect symmetry. Sounds simple, but was very challenging. As someone with a passion for aircraft myself, I knew that my customers (airplane people and pilots) would really pick up on anything inaccurate in the form, missing details, etc. in my interpretation of the Mustang.” Photo: via Jeff Krete

While Krete is a naturalist to his very bones, he is, like you and me, an inveterate aero geek—transfixed by the brute power and muscular technology that mankind has invested in its interpretation of nature’s elegant avian beauty. What it lacks in efficient, delicate and evolutionary optimization, the Vintage Wings of Canada P-51 Mustang compensates with speed, mass, noise, and a man-made beauty that cannot be denied. Artist Krete is a long-time friend of Vintage Wings, where he took measurements and made photographic studies of our Mustang for a bronze sculpture of North American Aviation’s most beautiful creation. Photo: Marna Krete

Details of the basswood sculpture of the P-51 Mustang and its vanquished quarry (FW-190). “I conducted much research, photographing real P-51s at air shows, at Vintage Wings of Canada and at Florida’s Stallion 51 for this.” said Krete, “I purchased a full set of P-51 blueprints, 3-view drawings and assembly/repair manuals to help with the lines and details of the aircraft. In my experience, I find that working in miniature is every bit as difficult as carving something full-size. The further you get into the details, the larger the piece becomes. It’s kind of like you have to ‘zoom in’ as you carve and add detail. The more you zoom in, the more detail there is to put into it. The challenge is to know when to stop or how much detail is appropriate or is enough. I obsess over the details and often have trouble knowing where to stop. There are also limitations for the bronze process to follow so that has to be a consideration. I feel I have achieved a standard of accuracy beyond what you may have seen in the past with similar work. At the end of the day, the work still has to be a piece of sculpture, not a model.” Photos: Jeff Krete

Details of the process of creating a mould of the Mustang carving. Each step of the process was a learning experience for the artist, who has the moulds and bronze castings made in a foundry in Japan. “I find the ancient ‘lost wax’ bronze casting process fascinating.” says Krete, “Recreating an art piece in metal and all of the steps necessary to complete it is very interesting. Moulding, casting wax, chasing the wax (restoring lost detail), making the refractory mould, metal casting and chasing the bronze (repairing lost detail) are all very labour intensive steps. Each finished piece cast requires all of the same steps and number of hours to complete. There is little in the way of ‘economies of scale’ when casting bronze pieces. Interestingly, the P-51 itself is cast in one piece.” Photos: via Jeff Krete

There is much work in the finishing of the cast sculpture. Welding components, cleaning and re-detailing areas affected in the casting and welding process and then patina application. “Patination” is a craft with a long history. Many secret recipes and techniques are used to achieve a variety of colour and visual textural differences in the finish. The colour palette is somewhat limited but is traditional and the very nature of this process. Photos: via Jeff Krete

The stunning complete work of art, titled “Cloud Dancer” stands 22 inches high, mounted on a granite base. The smoke streaming from the Mustang pilot’s quarry—a Focke Wulf FW-190 sculpted in abstract detail—forms the attachment point for the Mustang as she rolls and dives to follow her foe to the clouds below. Photo: Jeff Krete

The detail on bronze is astonishing, but Krete has to pull back from adding too much, as this not only becomes too difficult for the bronze technique to hold, but it could take the piece from the realm of fine art to a meticulously and overly detailed model. The patina created by the Japanese artisans is exquisite, highlighting the beautiful form of one of the greatest aircraft of all time. Photo: Jeff Krete

So as not to detract from the powerful detail of the Mustang, the true star of the piece, Krete chose to render the burning Luftwaffe Focke Wulf in a more abstract form. The patination techniques applied by the Japanese foundry artisans highlighted the flames streaming from the cowling as the wounded BMW engine breathes its last. Photo: Jeff Krete

In 2010, founder of Vintage Wings of Canada, Michael Potter thanks Krete for his donation of a copy of Cloud Dancer to raise funds for the organization he believes deeply in. Photo: Marna Krete

Krete looks on nervously as P-51 Mustang mechanic Paul Tremblay takes a close look at the detail and accuracy of the bronze Mustang sculpture. Tremblay, now Vintage Wings of Canada’s Director of Maintenance, gave it his seal of approval. Photo: Marna Krete

Krete’s next fighter aircraft in bronze will be the Messerschmitt Bf-109E. The 109 “Emil” was the most highly produced and most valuable fighter of the Luftwaffe in the Second World War and the nemesis of many an Allied airman. The famous fighter’s many fairings, protuberances, and brutalist form gave it a deeply menacing appeal. Nowhere near as lovely as the Mustang or Spitfire, the 109 captured the imaginations of young boys on both sides of the war for its mean, Teutonic and industrial qualities. If any aircraft represented the enemy, it was the evil lines of the Messerschmitt. Photos: Jeff Krete

Avian Fusion

For century upon century, Man has looked to the sky with envy, as birds wheeled in joyous freedom, flashing with lightning speed, hovering without effort. Out of this envy rose one of mankind’s greatest obsessions—to fly above the earth and travel effortlessly to far-off places. From the outset, birds were given godlike status in mythologies and cultures from ancient Egypt to the great aboriginal civilizations of the Northwest Coast of Canada. Man understood that the only way to become godlike and fly like a bird was to emulate avian wings. Trial after trial resulted in error after error. Man’s earliest attempts with lightweight wood frames and real feathers proved not only disastrous, but that man had no clue how wings actually worked.

By the time the 19th century rolled over, people like George Calley and Otto Lilienthal had established the fundamentals of aerodynamics and had conducted the first successful gliding experiments with flight. Meanwhile, birds kept joyously flying all over the planet. It took another few decades before man had mastered three-axis control of flight and found a way to get an aircraft into the air without jumping from a cliff. Man finally was flying like a bird, though not so elegantly.

During the 15th century, the man who gave a face to the term “renaissance man”, Leonardo da Vinci was one of the first to begin to contemplate how man-made materials might someday be used to make a wing which produced the ability to fly. By the 19thCentury, men like Otto Lilienthal were realizing da Vinci’s dream in machines that were surprisingly similar to this da Vinci sketch from 400 years earlier. Image: Leonardo da Vinci

For eons, man has longed to fly like the birds around him. Ancient myths from all cultures made god creatures that could fly and those other mythic characters that were killed in the attempt, like Icarus, were destined to become symbols of hubris and folly. Here, in a melodramatic, late 19th century painting called “Lament for Icarus” by Herbert James Draper, water nymphs weep for the fallen youth. Icarus is the subject of literally thousands of paintings over the years. When man would eventually fly, it would be with wings of a different nature. Image: Tate, London

Birds begat the world of airplanes, but since the first flights of the Wrights and other innovators around the world, the only time avian flyers and human flyers got together was in the form of bird strikes. Birds, the source of inspiration that fired imaginations, fuelled a centuries-long quest, and spawned an industry, deserve so much better.

Artist Jeff Krete followed two similar and parallel lines of artistic endeavour for years—one avian, one aeronautical—when suddenly those two lines veered sharply toward each other. A year ago, Krete’s imagination took hold of an idea to express both of his loves in one breathtaking piece blending the natural beauty of bird flight with the mechanical representation of manned flight. The result would shatter the conventions of traditional bird carving, yet win him another World Championship.

To represent the inspiring beauty of flight, Krete chose to base his piece around the exotically formed wings of a female great frigatebird, one of the astounding ocean flyers of the Pacific. The frigatebird is an extremely large bird with a length of up to 41 inches (105cm) and a stunning wingspan of up to 90 inches (7.5 feet or 230 cm). Yet the largest would weigh less than 3.5 pounds (1.5 kilos). The frigatebirds have the highest ratio of wing area to body mass and the lowest wing loading of any bird on the planet. Its huge sculpted wing combined with its light weight provides the frigatebird with exceptional flying abilities. They appear as massive black kites, seeming to hover on thermals, almost motionless.

A pair of frigatebirds in flight near the Galapagos showing their distinctive, uber-efficient and dramatic wing form. It was images like this that energized Krete to turn a carving of a frigatebird in flight into a powerful statement of man’s progress in emulating avian ability with sustained and unpowered flight. Photo: wsgpete at deviantart.com

The frigatebird’s wings are a result of eons of evolutionary development, trillions of hours of in-flight testing, and nature’s brilliance—the perfect wing to express man’s ancient desire for flight in art form. Photo: Wikipedia

The female frigatebird on the wing. These huge yet light animals got their name from their piratical practices of stealing chicks from other bird’s nests and engaging in kleptoparasitism—stealing prey caught by other birds.

The frigatebird’s astounding evolution into a transcendent flyer could not be counterbalanced in Krete’s design with the heavy wings of an ungainly aircraft. For the frigatebird to morph into man flight, Krete chose the frigatebird of German glider design of the 1930s—Alexander Lippisch’s infamous Fafnir sailplane. The Fafnir, like the frigatebird, has extremely light wing loading—a 62-foot wingspan and an empty weight of just under 500 lbs.

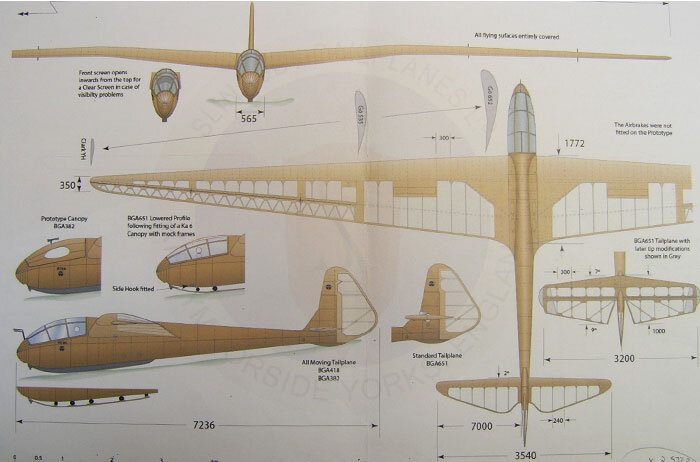

Krete took inspiration for his bird-to-aircraft sculpture from one of the finest and most extreme of all early gliders—the “Fafnir”glider by famed German aerodynamicist Alexander Lippisch. The name Fafnir comes from Norse mythology—the son of a king who is cursed and becomes a dragon. The fine detail, extreme fairing and sleek lines emulated the great soaring birds of the world’s oceans. Its structure would be the basis of the frigatebird’s transition to aircraft form.

Lippisch’s work not only inspired Krete’s work, it had some impact on the Supermarine Spitfire. Canadian aerodynamicist Beverly Shenstone, the designer of the Spitfire’s most famous feature—its elegant elliptical wing form—apprenticed with Lippisch’s design studio in the early 1930s. Here we see one of Germany’s great glider pilots, Günther Groenhoff, wedged into the highly faired cockpit of the Fafnir. Groenhoff, a rising star in the world of pre-war gliding and test flying, was killed in an accident with the Fafnir—at the young age of 23. Image via www.scalesoaring.co.uk

Günther Groenhoff, shortly before his death in a gliding competition in 1932. Photo: www.scalesoaring.co.uk

A purchased set of plans of another famous glider, the Slingsby Petral inspired the structural components of a new sculpture which would push Krete’s artistry to new levels of technique and whimsy. Photo: Jeff Krete

The resulting blend of frigatebird and Fafnir is an astonishing piece of artwork and creativity which energizes all who look upon it and exudes both avian and aero spirituality.

I just this day shared the images of Krete’s Fafnir-Frigatebird wing with professional test pilot Rob Erdos. Erdos has flown close to 150 types of aircraft from the Messerschmitt Bf-109 to the C-17 Globemaster III. One look at that wing imagined by Krete and he said, “In the right conditions and balance... that appears to be a flyable wing.”

The following photographs depict the agonizing hours of research, planning and work that went into Krete’s “Anatomy of Flight”—a tour de force piece by a man who has been in love with flight all his life. I can relate to that.

Dave O’Malley

With drawings reminiscent of da Vinci’s early sketches of a flying machine, Krete works out the details of a very ambitious new project—to portray the avian roots of manned flight in the form of a half bird/half mid-century aircraft. Photo: Jeff Krete

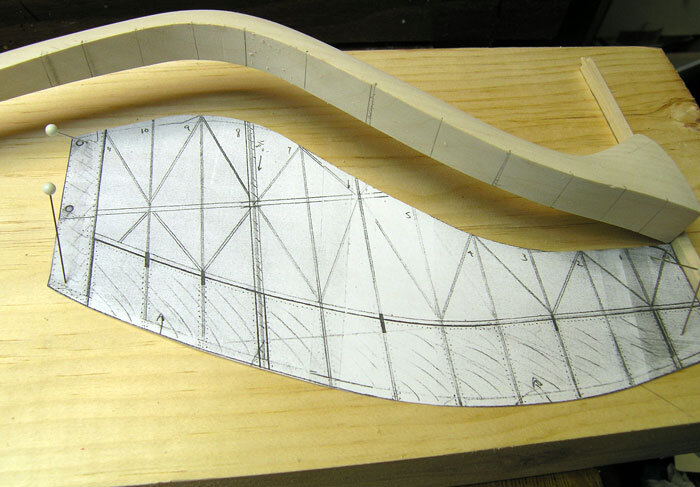

The outer wing structure and control surfaces owe their inspiration to the structural elegance of the Fafnir’s unique wing. Photo and sketch by Jeff Krete

Krete’s rough base carving of the wing is attached to the frigatebird’s more detailed body to enable the artist to carve the transition of the wing to body. One can understand the scale by comparing it to the pencil in the image. Photo: Jeff Krete

Using a Dremel power tool, Krete carves the surface of the avian wing of the bird-machine. The detail includes every vane and rachis of every flight feather. Though all of the artist’s works look appealing in bare basswood, they are all destined to be hand painted to depict the exact markings and tones of the real birds they portray. Photo: Jeff Krete

On the aircraft side of the sculpture, the wing has the same proportions as the avian side but resembles an exposed wing structure. Here, Krete carves the solid leading edge of the wing, or D-box, and lines it up with structural sketches he has made for the wing—a blend of a frigatebird’s dramatic wing form and the structural layout of Lippisch’s Fafnir glider. Note the size of the stickpins—indicating the small scale at which Krete works. Photo: Jeff Krete

On the avian side, feathers and wing warping enable controlled flight, while on the aircraft side, Krete’s frigatebird aircraft will need ailerons. Here the artist begins the time consuming construction of the control surface. Photo: Jeff Krete

The artist begins building out the wing structure, with space for the attachment of the aileron at a later stage. In the background stands the carved avian right wing. Photo: Jeff Krete

With special tools he has developed himself, Krete works detail into the wing—rivets, seams, access panels and fuel filler caps. The aileron is now in position. Photo: Jeff Krete

The gorgeous natural shape of the bird-machine’s left wing is nothing short of breathtaking. The trailing edge connection piece presented difficulties to the artist who steamed the wood to conform to the complex curves. Photo: Jeff Krete

The lines of rivets are made with a special wheeled tool that scores the surface in a regular pattern. Photo: Jeff Krete

The right wing is not fully an avian wing, with the bird character giving way to the surface of an aircraft wing. The sense of the aircraft structure is exquisitely portrayed while keeping true to the frigatebird’s natural form. Photo: Jeff Krete

Carved from a solid block of basswood, the body of the frigatebird is hollowed out to represent the internal structure of an aircraft fuselage. Photo: Jeff Krete

The detail of the frigatebird’s body includes a blend of feather and aluminium. The bird’s skull has carved details of a cockpit canopy and even the addition of a P-51-style flare tube outlet behind the eye. The artist is clearly having fun imagining a frigatebird-inspired aircraft in all its detail. Photo: Jeff Krete

The early stages of the painting process. Here, the colour differences in the wood and the dremel burning disappear beneath a covering of dark acrylic artist’s paint. Note the subtleties of how the feathers transform from natural detail to pure shape and then to aluminium. Photo: Jeff Krete

The finished piece, entitled “Anatomy of Flight”, depicts a greater frigatebird in a sustained glide—half aircraft, half bird. Photo: Bill Einsig, courtesy of the Ward Foundation

Detail of the completed left wing—an elegant structural interpretation of one of nature’s finest flying geometries. In contrast to the natural black feathers of the right wing, the left wing is portrayed in a darkened metal finish. Photo: Bill Einsig, courtesy of the Ward Foundation

A close-up of the wing’s leading edge reveals the dirt and staining of a working aircraft and slipstream streaking of oil and fuel leaking from filler caps. This creates a patina of reality which balances perfectly with natural detail on the right wing. Photo: Bill Einsig, courtesy of the Ward Foundation

From the low aft quarter, we see the fuselage structure and the contrast between the aerospace wing and the natural wing. Photo: Bill Einsig, courtesy of the Ward Foundation

The bird-aircraft has both types of landing gear. The single centreline wheel, typical of early gliders, contrasts almost humorously with the frigatebird’s natural foot. The leg and toes on the bird’s right foot are carved in steel rod, brazed together and formed into an accurate avian structure grasping onto the aluminium support piece. No other hardware is used here. The foot is literally holding on and supporting the entire sculpture. Photo: Bill Einsig, courtesy of the Ward Foundation

Krete strove to include a human element in the piece and whimsically demonstrates this with cockpit canopy windows, carved in the fenestration style of the 1930s and 1940s. The frigatebird was the perfect canvas for all of the aircraft elements Krete wanted to replicate in the final piece. Note the P-51-inspired pilot’s flare tube on the face just below the canopy. Photo: Bill Einsig, courtesy of the Ward Foundation

The resulting Anatomy of Flight work was caused quite a stir at the recent 44th Annual World Championship Wildfowl Carving Competition and Art Festival in Ocean City, Maryland. Krete was awarded World Champion status with a First Place in the Interpretive Wood Sculpture category. The upwardly sweeping support piece is cut from 5052 aircraft grade aluminium. Photo: Bill Einsig, courtesy of the Ward Foundation