THE CANADIANS — In the Battle of Britain

It simply cannot be overstated. In the summer of 1940, Great Britain was well and truly up against the wall. Its army, decimated in France, was lucky to be pulled from the jaws of total annihilation on the beaches of Northern France. With the army licking its wounds, and the Royal Air Force with heavy losses in France, the population of Great Britain fully expected that there would soon be door-to-door fighting in London, in York, or in Kent. While the RAF, Navy and Army steeled themselves for coming fight, the ordinary people of Great Britain were readying themselves as well—for a fight to the death on sacred British soil. In anticipation of a Nazi invasion on British beaches, the British government had printed a poster which was to be posted in the event the Germans came ashore. It said in simple large letters beneath the King’s crown, “Keep Calm and Carry On”. It was never used. It would only surface 65 years later and become a modern day icon for stick-to-it-iveness.

Though disaster was just over the horizon, there was one last battle to be fought—a battle like no other in history. This was the Battle of Britain. The Battle, the aircraft and the nearly 3,000 men who flew in the defence of Great Britain live today as unparalleled icons of courage and determination in the face of almost certain defeat. Its inspirational effect on Great Britain and the hundreds of thousands of young men and women who, upon hearing the story, would enlist in the RAF, RCAF, RAAF, RNZAF and SAAF is unquestionable. It not only stopped the advance of the dark stain of Nazism, it turned the tide.

It is the story of a courageous few and a steadfast country. The part played by Canadians, while small in numbers, was great of heart. We stood shoulder to shoulder with other pilots of the British Commonwealth, occupied Europe and even America. The summer of 1940 is the stuff of legend. — Dave O’Malley

The Battle of Britain – the Canadians.

By 18 June 1940, the Germans had overrun all of Western Europe. France had finally surrendered and the British had evacuated their remaining troops through Dunkirk in a remarkable across-the-Channel withdrawal made possible particularly by fleets of boats and small ships from the UK largely manned by civilian volunteers. The RAF was able to provide the control of the air essential to safe passage.

Facing reality about the oncoming fight, Churchill stated: “Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilization. The whole might of the enemy must soon be turned upon us. Let us…so bear ourselves that men will say ‘this was their finest hour’ ”. It was to be a battle of survival for Britain.

The fact is that in 1940 just under 3,000 young airmen changed the course of history and established the foundation upon which democracy would build to achieve its final victory in Europe. The purpose of this article is to tell how they did it.

The Battle of Britain is unique in that it is the first and only time that airpower alone defeated a major threat to a nation’s very existence.

Following Dunkirk, the Germans mounted their air campaign aimed at eliminating Britain’s ability to ward off a cross-Channel seaborne invasion. By late summer 1940, the German operation, code-named Operation SEA LION, was to follow immediately after the Luftwaffe had gained control of the air and destroyed other threats.

SCRAMBLE!!! Fighter pilots of the Royal Air Force grab their kit and run towards their aircraft. There are many evocative photographs taken in the summer of 1940 of young men like these, running to their possible deaths in the skies over England. During the Second World War, it is noted that, while fighting the Nazi onslaught, pilots wore shirt and tie. Many of these photos were staged for propaganda purposes, and if you look closely at any one of them, you are likely to find a pilot smirking sheepishly. Photo: Imperial War Museum

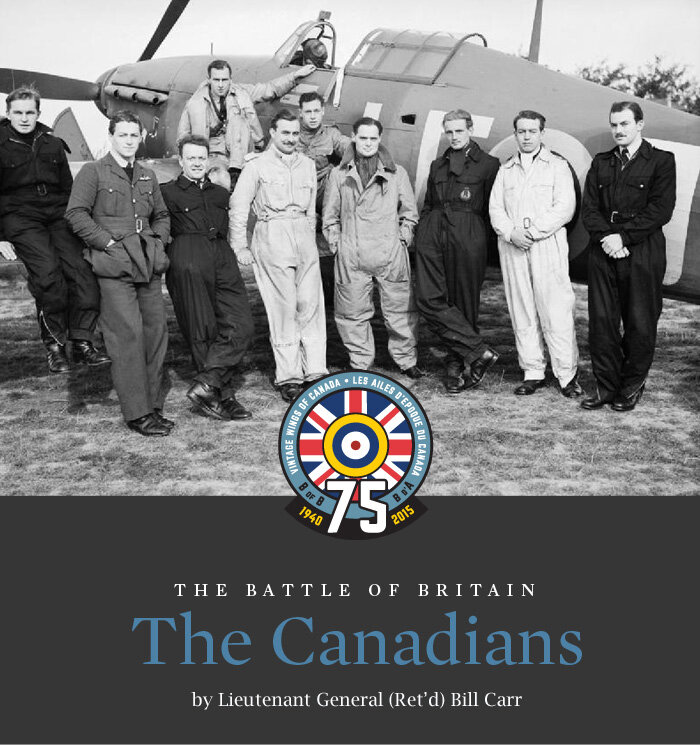

Among the greats. Douglas Bader (fourth from right), the English flying legend, commanded 242 Canadian Squadron RAF. At the beginning of the war, the RCAF had not yet equipped and assembled squadrons for deployment in Europe. There were however many Canadians who were either in the RAF, or who were RCAF in the Royal Air Force. In order to show Canadians back home that their boys were fully engaged in the war, it was decided to create a special squadron (242) manned by Canadians already in the RAF. This squadron assembled some of the finest talent of the war—young fighter pilots from across the land, now seen fighting the Nazis as a cohesive unit. This photograph was taken at RAF Duxford in September of 1940. Left to right: Future Air Marshal Sir Dennis Crowley-Milling, KCB, CBE, DSO, DFC and Bar, AE (Wales), Flight Lieutenant Hugh Tamblyn, DFC (Watrous, Saskatchewan), Stan Turner, DSO, DFC, CD (Collingwood, Ontario), Sergeant Joseph Ernest Savill (on wing, British), Pilot Officer Norman Neil Campbell (St. Thomas, Ontario), Flying Officer Willie McKnight, DFC and Bar (Calgary, Alberta), Douglas Bader, Flight Lieutenant George Eric Ball, Pilot Officer Michael G. Homer and Flying Officer Marvin “Ben” Brown (Kincardine, Ontario). Within a year, McKnight, Tamblyn, Campbell, Homer and Brown would be dead. Bader would be shot down and captured and Ball would die in a flying accident having just survived the war. Photo: Imperial War Museum

It is generally agreed the Battle of Britain can be divided into four stages: From 10 July to 7 August, the first stage, the Luftwaffe attempted to destroy the RAF’s radar towers which it knew were vital to the Britain’s air defense tactics. Simultaneously, German bombers were bent on destruction of Britain’s ability to fight back by neutralizing its defenses, crippling its infrastructure and breaking civilian morale. Despite the German raids, and much overlooked, RAF Bomber and Coastal Commands were indeed active in attacks on the French Ports from which the German invasion fleet could be launched.

During the second stage, 8 August to 6 September, the Luftwaffe mistakenly believed it had destroyed much of the RAF early warning radar capability and now aimed to destroy the RAF on the ground by bombing its airfields. This put further pressure on the RAF. However, the RAF’s ongoing success in the, until then, mainly daylight air war, confronted the Luftwaffe with such aircraft and aircrew losses that by October the Luftwaffe had largely switched to night raids.

One of these early bombing raids had killed civilians in London. The result was dramatic to both sides. Hitler had specifically directed that attacks against civilian targets were not to be carried out, because he believed that eventually the British people would sue for peace, and he hoped to be seen to have no fight with the British people.

On the other hand, the British reaction to this raid on London was to bomb Berlin. Hitler raged over this unexpected counterblow by the British and ordered attacks by his bombers on civilian targets in the UK. This changed everything and led to the third stage of the Battle which ran from 7 September to 5 October. The Blitz began.

This change in tactics by the Germans was a mistake for other reasons, but it did relieve the pressure on the RAF airfields. To reach industrial targets and built-up areas, Luftwaffe Bombers and their Messerschmitt Bf-109 escorts were forced to operate close to the limits of their range, and were thus inhibited in their freedom to maneuver in their own defense. Added to this problem for the Germans, was the growing availability to the RAF of rudimentary airborne intercept radar. German losses became intolerable. This was the fourth phase.

The battle didn’t end in a finite way, but rather ran down because Hitler was finally convinced that Air Superiority over the Channel to defend the invasion fleets from air attacks could not be gained, and defeat of the RAF and his dream of negotiating a peace were unachievable. On 21 October, Hitler put off Operation SEA LION and ordered his forces and their matériel, which had been amassed for the invasion, to be withdrawn from Western Europe and dispatched to the Russian Front.

Of the 2,962 allied pilots engaged in the Battle of Britain, 2,421 were RAF (and Fleet Air Arm), 117 were Canadian, 141 were Polish and a further 210 were from ten other countries. 515 of them including 29 Canadians were killed.

Four of the Fighter Command Squadrons which took part in the Battle had links with Canada. The link was evidenced in each of these units’ badges. No. 73 Squadron flying Hurricanes had a Canadian contingent, No. 92 Squadron flying Spitfires was a Canadian unit in the First World War, No. 242 Squadron flying Hurricanes had a Canadian Moose head in its badge and the future No. 401 RCAF Squadron. This Squadron had arrived in the UK on 21 June 1940 with its own Hurricanes as No. 1 RCAF Squadron.

Related Stories

Click on image

On 30 October 1940, at the end of the Battle of Britain, surviving pilots of No. 1 Squadron RCAF pose in more formal dress with one of their Hurricanes at Prestwick, Scotland. No. 1 Squadron RCAF left for Great Britain in June of 1940, with the Battle well under way. After a short period of training in England, they became the only RCAF Squadron involved in the Battle of Britain, first engaging the enemy on 23 August 1940. The following year, No. 1 became 401 Squadron. 401 Squadron ended the war as the RAF 2nd Tactical Air Force’s highest scoring fighter squadron with 186.5 victories—29 of which were earned during the Battle of Britain. Left to Right: Frank Hillock, Toronto ON; Frederick Watson, Winnipeg MB; Robert Norris, Saskatoon SK; Norman Richard Johnstone, Winnipeg MB; Joseph A. J. Chevrier, Saint-Lambert QC; John David Morrison, Regina SK; Gordon McGregor, Montréal QC; Arthur Yuile, Montréal QC; Paul Pitcher, Montréal QC; William Sprenger, Montréal QC; and Dean Nesbitt, Montréal QC. It is interesting to note that all five men on the right are from Montréal. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The brunt of the air battle was borne by the Hawker Hurricane and the Supermarine Spitfire. While many of the aircraft and pilot numbers are still debated, it is most probable that at the outset of the Battle, 615 Hurricanes and 324 Spitfires were assigned to the task. At the end in October, despite a steady replacement of losses, the strength was 512 Hurricanes and 281 Spitfires. However, a total of 526 Hurricanes and 389 Spitfires had been lost. They had accounted for (actual – not claimed) 1,733 German aircraft shot down. The RAF’s loss of 915 aircraft was far fewer than the 3,058 claimed by the Germans.

The Hurricane accounted for 1.8 German aircraft shot down for every Hurricane lost and the Spitfires accounted for 2.0 German aircraft for every Spitfire lost. However, the Hurricanes accounted for 55% of the total air victories and the Spitfires 45%. Was the Hurricane therefore the better aircraft? The answer is No! There were many more Hurricanes than there were Spitfires. (And bragging rights as to which was better still goes to him who speaks the loudest!)

Finally, though, as to which was best, of the seventeen double aces to earn this recognition, ten had flown Spitfires and seven had flown the Hurricane!

Royal Air Force and Luftwaffe fighters and bombers are knotted in combat high above Maidstone, England in 1940. The condensation vapour trails in the high altitudes trace the battle as it unfolds. Many of the contrails can be seen in pairs as either “lead and wing” turn, wheel and fight together or a fighter is locked on another in mortal combat. This chalkboard of the fight could be seen on many days through the hot humid summer of 1940. Photo: Gullands-Heritage.co.uk

Canadian pilots accounted for 194 Luftwaffe losses. The top Canadian scorer was Flight Lieutenant Mark Brown, DFC and Bar, with a total of 15 during the battle.

At the age of 39, the oldest Canadian pilot to take part was Flight Lieutenant Gordon McGregor, DFC OBE. His score was five enemy fighters. Retiring as a Group Captain, he will also be remembered as the inspired leader of Canada’s Trans Canada Air Lines after the war’s end. The youngest Canadian pilot in the Battle was 19 years old, Leo Ricks from Calgary. He was a member of 235 Squadron.

Arguably, the most famous pilots to have fought in the Battle of Britain were the RAF’s Group Captain Douglas Bader, the ‘legless’ ace, RAF’s F/L (later Air Vice Marshall) Johnnie Johnson, who at war’s end was the top allied ace in the European theatre, and on the Luftwaffe side the unequaled Adolph Galland.

Air operations ‘petered out’ to quote one author on 21 October and the end was officially declared reached on 31 October. The Battle of Britain was a triumph of indomitable human spirit against a numerically superior enemy led by a maniac. In retrospect, the manner in which a relatively small number of brave young airmen victoriously defended the British Homeland is as remarkable now as then.

Already in August 1940, Churchill said, in part, “The gratitude of every home in our island, in our empire and throughout the world… goes out to airmen who undaunted by odds, unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger helped turn the tide of the world war”.

Canadian airmen flew shoulder to shoulder with the best from elsewhere. The ‘Few’ were unique and not unlike their contemporaries later, and consciously or not, upheld the airman`s credo of honour which was never to be found wanting when the chips were down.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s words of praise and thanks, seventy years ago, are still valid: “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed to by so many to so few.”

A Few Canadians of Note in the Battle of Britain

Group Captain Gordon Roy McGregor, OC, OBE, DFC (a squadron Leader by the Battle’s end) of Montréal, Québec learned to fly in the early 1930s after earning a degree in engineering from McGill University. He joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1936, receiving his wings two years later. The handsome McGregor was the oldest Canadian-born pilot in the Battle of Britain, becoming a Hurricane ace during the Battle with 401 Squadron (then called 1 Squadron) RCAF. With five confirmed victories, he was the squadron’s top scoring fighter pilot. McGregor’s Second World War career would include commanding X Wing—a Canadian wing of Kittyhawk fighter on operations in the Aleutians. Later, towards the end of the war, he commanded 126 Wing, a Canadian Spitfire Wing in Europe. After the war, he went to work as an executive for Trans Canada Air Lines, becoming its president a few years later. He then was instrumental in transforming TCA into Air Canada, still the largest airline in Canada today. Photo: AcesofWW2.com

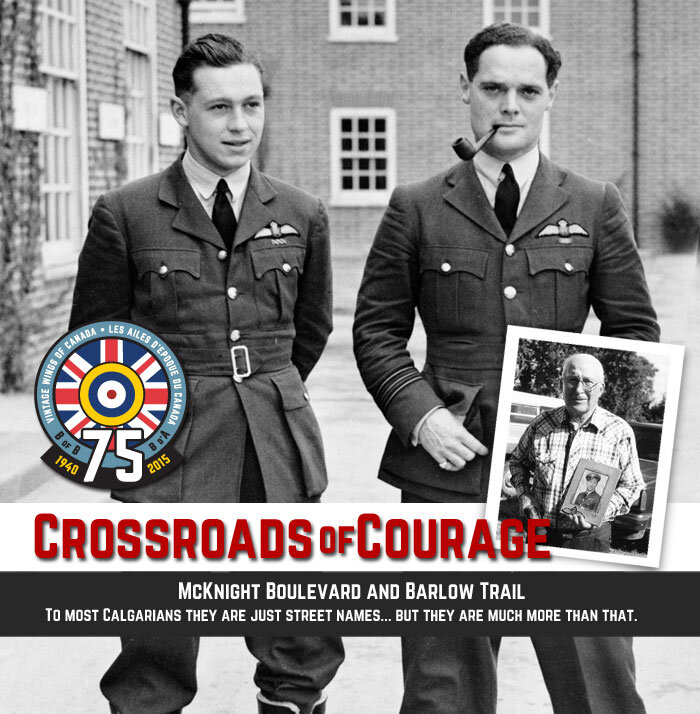

Flight Lieutenant Mark Henry “Hilly” Brown, DFC and Bar (left) was born in the tiny farming town of Glenboro, Manitoba in 1911. Given the flat prairie landscape of his hometown, it’s a wonder where he got his nickname. He received his wings from the Royal Air Force in 1938, and following actions in both the Battle of France and the Battle of Britain, he became the first Canadian ace of the Second World War. By the time of his death in November 1941 while on a fighter sweep from Malta, he had achieved Triple Ace status. The citation accompanying the award of his first Distinguished Flying Cross reads: “Since the beginning of the war Flight Lieutenant Brown has destroyed at least sixteen enemy aircraft. On 14th June, when leading his flight on patrol, he encountered nine enemy bombers, two of which were destroyed. Later he attacked nine Messerschmitt 109s, destroying one and driving the remainder off. As a result of bullets entering his aircraft he force landed near Caen, and was unable to rejoin the squadron before it withdrew from France. Flight Lieutenant Brown has shown courage of the highest order, and has led many flights with great success and determination when consistently outnumbered by enemy aircraft.” The citation for his second DFC reads “This officer has commanded the squadron with outstanding success. He has destroyed a further two enemy aircraft bringing his total victories to at least 18. His splendid leadership and dauntless spirit have been largely instrumental in maintaining a high standard of efficiency throughout the squadron”. The pilot next to him in this photo is named Pilot Officer Chatham. The photo was taken at RAF Huntingdonshire. Photo: Imperial War Museum

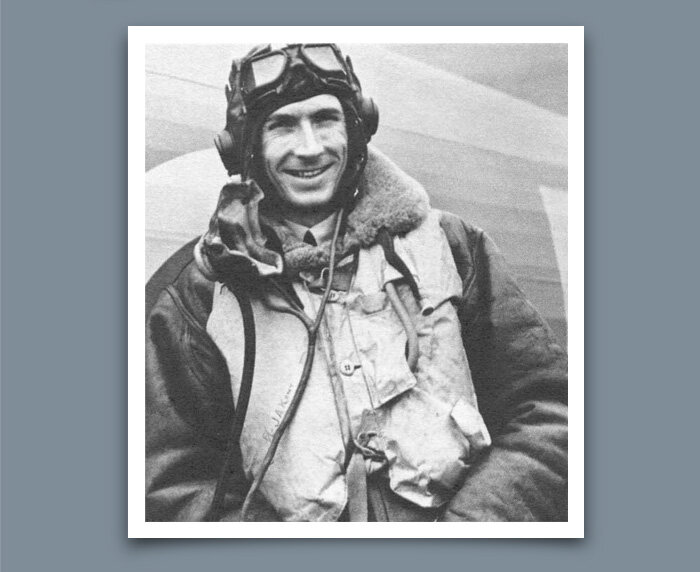

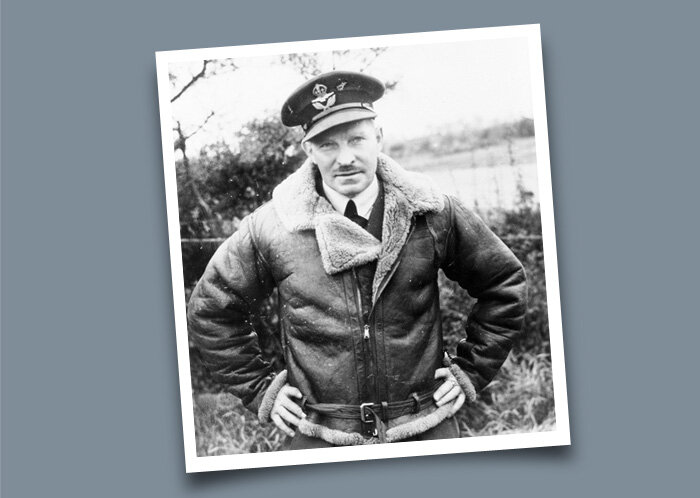

Flying Officer William Lidstone McKnight, DFC and Bar, of Calgary, Alberta is perhaps the most celebrated Canadian of the Battle of Britain. McKnight, jilted by his girlfriend whilst attending medical school at the University of Alberta, quit his studies and travelled to England on his own money to enlist in the Royal Air Force in 1938. McKnight, an enfant terrible with his wild, rebellious ways, cut quite the swath through his squadrons, being confined to barracks on two occasions, held in open arrest as “perpetrator of a riot”. McKnight was credited with 18 victories and was Bader’s preferred wingman. He survived both the Battle of France and Britain, but was shot down over the English Channel in January of 1941. He was the fourth highest scoring Canadian fighter pilot of the Second World War. Photo: RAF

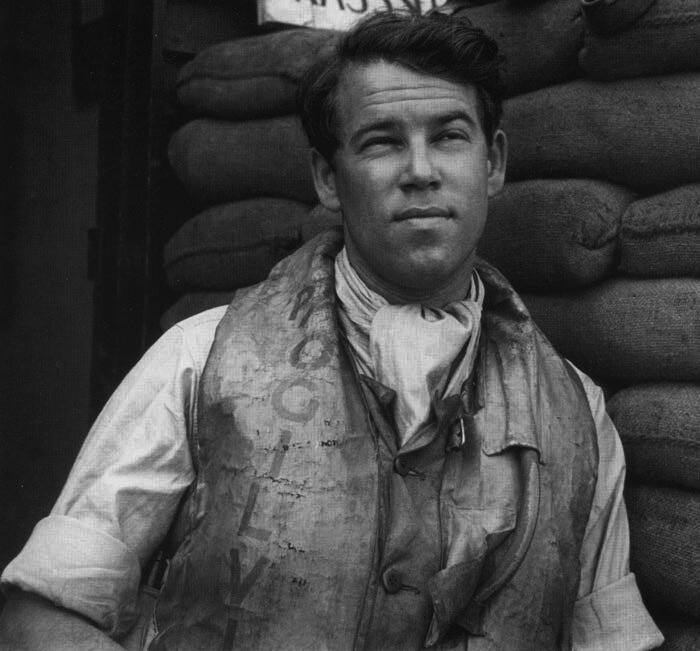

Sir John Maxwell “Max” Aitken, 2nd Baron of Beaverbrook, was the son of Lord Beaverbrook, the prominent Second World War politician. Aitken was born in Canada, but was educated in England. He became the commander of 601 City of London Squadron at the height of the Battle of Britain, flying Hurricanes and ended the war with 14 confirmed victories. He flew with and was a friend of the famous fighter pilot memoirist Richard Hillary. He was featured in Hillary’s famous book The Last Enemy. This photo was taken of him in front of a Mosquito fighter-bomber later in the war when he commanded the Banff Strike Wing. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Winnipeg-born Group Captain John Alexander “Johnny” Kent, AFC, DFC and Bar, is a true legend of the Battle of Britain. He began his flying war as a Spitfire photo-recon pilot with the Photographic Development Unit. He was shot down whilst on a low-level sortie in France, but survived. He then joined 303 Polish Squadron, RAF in command of “A” Flight. He earned the love and admiration of his Polish pilots, many of whom spoke no English. He eventually led the entire Polish Wing of four squadrons, thereby earning himself the nicknames Kentowski and Kentski. Of the four Polish squadrons in his charge, he had this to say: “I cannot say how proud I am to have been privileged to help form and lead No. 303 Squadron and later to lead such a magnificent fighting force as the Polish Wing. There formed within me in those days an admiration, respect and genuine affection for these really remarkable men which I have never lost. I formed friendships that are as firm as they were those twenty-five years ago and this I find most gratifying. We who were privileged to fly and fight with them will never forget and Britain must never forget how much she owes to the loyalty, indomitable spirit and sacrifice of those Polish flyers. They were our staunchest Allies in our darkest days; may they always be remembered as such.” Kent accounted for 13 enemy aircraft shot down. Photo: RAF

Flight Lieutenant Hugh Tamblyn, DFC was born in Watrous, Saskatchewan in 1917. Twenty-one years later, he joined the RAF on a short service commission. He started his flying career as a staff pilot for No. 7 Bombing and Gunnery School in England. Following this service, he joined 141 Squadron. The unit flew the Boulton Paul Defiant turret-fighter, which, while somewhat effective against bomber formations, was hopelessly outclassed by German Bf-109s. On 19 July, in the Battle of Britain, he was one of only two pilots in a flight of nine Defiants to survive a mauling by Messerschmitt Bf-109s. His turret-gunner claimed one of the Messerschmitts. In August, he joined 242 Canadian Squadron and in September 1940, claimed 5 victories. In April of 1941, he was shot down by return fire from a Dornier Do. 17. He crashed into the sea and got out of his Hurricane, but died of exposure and hypothermia before he could be rescued. Photo: Imperial War Museum

While Percival Stanley “Stan” Turner, DSO, DFC and Bar, was born in England, his parents emigrated to Toronto, Ontario when he was a small child. While enrolled at the University of Toronto in engineering, he enlisted in the RCAF auxiliary. In 1938, he sailed the Atlantic and joined the Royal Air Force on a short service commission, completing his flying training in 1939 at the outbreak of the war. He joined 219 Squadron on Hurricanes, but when the idea of a squadron of fighting Canadians took hold, he moved over to 242 Squadron a month later. Turner survived the war with 12 victories and the distinction of being the Canadian pilot with the most combat tours. Stan Turner is a member of the Canadian Aviation Hall of Fame. Photo: Imperial War Museum

At the time of the Battle of Britain, the diminutive but feisty Ernest Archibald McNab, OBE, DFC of Saskatchewan was, at 35, much older than the pilots in his No. 1 Squadron, but he flew with youthful abandon. He enlisted in the RCAF in 1926, earning his pilot brevet in 1928. He took command of No. 1 Squadron in November of 1939 and took his squadron overseas to join the fight in June 1940. Between the wars, McNab was a member of Canada’s fort military aerobatic demonstration team—The Siskins. Photo: RCAF

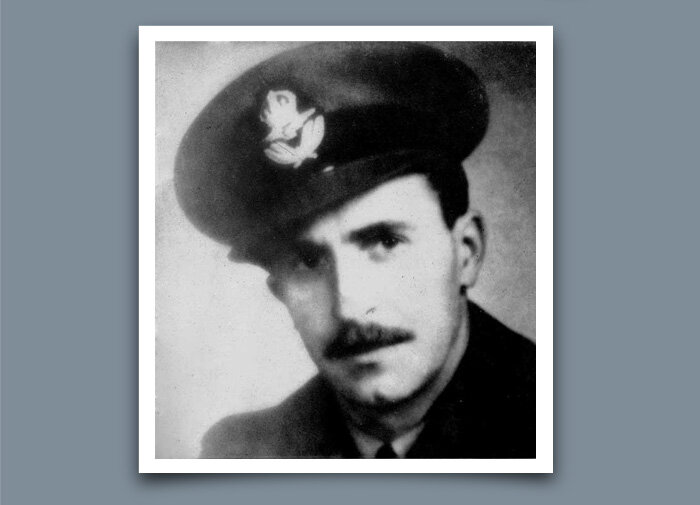

Pilot Officer Joseph Paul Larichelière was bilingual, elegant and university educated, one of a large group of Canadian pilots who called Montréal home. Throughout the 1930s, he watched as the war loomed over the horizon, and when it seemed imminent in 1939, he joined the RAF, at age 26. By the time of his death, Larichelière was an ace with 6 victories. He and his fellow 213 Squadron pilots were scrambled to intercept enemy aircraft on 16 August. He did not return. Like many young men of the RAF and RCAF, he has no known grave. Photo: RCAF

The photogenic Pilot Officer Alfred Keith “Skeets” Ogilvie, DFC of Ottawa, Ontario was a former bank teller who joined the RAF on short service commission the summer before the Battle of Britain. His wish was to join 242 Canadian Squadron, but the unit was not in need of another pilot, so he joined 601 Squadron. He became an ace during the Battle of Britain. In 1941, while flying a Spitfire, he was seriously wounded and forced to bail out. He was captured and spent the next nine months in hospital before being transferred to Stalag Luft III POW camp. He helped plan the Great Escape, and managed to evade capture for 2 days. After recapture, he was interrogated and then sent back to prison—50 of his fellow escapees were not so lucky. When they were recaptured, they were executed. Photo: Imperial War Museum

About the author: Lieutenant General William Keir Carr was a photo-reconnaissance Spitfire pilot during the Second World War. The stories of the courage and determination of Canadian fighter pilots who fought in the Battle of Britain inspired wave after wave of young Canadian men like Carr to enlist in the RCAF and join the fight. By war’s end Carr had flown 142 operational sorties—alone and unarmed. After the war, Carr’s star continued to rise as he took one command after another. As Commander of 412 Squadron, he oversaw the operation of the first jet transport aircraft in any air force in the world—the RCAF’s de Havilland Comet. With the 412 Squadron Comet, the RCAF was the first ever (Civilian or Military) to operate jet transports on scheduled service over the Atlantic. At the end of his military career Carr was the first Commanding Officer of Air Command, and the acknowledged “father of the modern Canadian air force”. Today, even in his mid-90s he remains a force to be reckoned with and is often called upon for his wise and careful counsel. After nearly 75 years connected to the Royal Canadian Air Force, Carr’s words still carry much weight, and while his respect is mightily earned, he remains humble, often fighting with determination to shine light on other men, other battles, other Canadians.