A TERRIFYING BEAUTY - The Art of Piotr Forkasiewicz

In the black of night of 8 June 1944, two days after the D-Day invasions of Normandy, the dark hulk of a four-engined Lancaster bomber of 15 Squadron, Royal Air Force, trailing a blow-torching curtain of livid flame, lurches heavily into a dive over the French countryside, a few miles to the west of Paris. The flame is bright enough to illuminate the farms below in a pale and ghostly light. The big bomber is dying, her lifeblood streaming in angry, high octane sheets from her starboard wing fuel tanks.

Behind the Lancaster, a Luftwaffe night fighter follows her down to finish her off. Its cannons hammer continuously at the British aircraft, while their tracer rounds rocket and shriek past, trailing smoke, lit by the burning, streaming wounds of the Lanc. Beneath the Lancaster, escape hatches open and crew members, abandoning the dying aircraft while they can, tumble out into the slipstream like rag dolls. On the top side of the Lancaster, however, the mid-upper gunner, Robbie Aitken, with his back to the approaching French farmland, empties his ammunition boxes into the German, giving time for his crew to get out of the mortally wounded aircraft. The searing muzzle flashes of his twin Brownings stab the night like dragons, likely blinding the young gunner. Hot brass shell casings tumble unseen in the darkness to thud heavily into fields and villages below, while oily grey smoke, ghosted by the streaming funeral pyres, wakes behind from two of her engines.

The sound is the sound of hell. Four thundering Merlin engines. The foundry shriek and snap of wind-whipped flame. The rip saw burp of Aitken’s .303 Brownings. The heavy thump of the night fighter’s cannons. And perhaps above it all, the angry scream of Aitken as he fights to the end of his ammunition.

Some moments later, the comet-like apparition, a wraith trailing fire and foul smoke, engines screaming, slammed into the grounds of a French château between the village of Jouars-Pontchartrain in the Département des Yvelines and the town of Plaisir, some 5 kilometres to the northeast. It was followed by six parachutes, dropping silently along its smoking path. The first five landed in the blacked-out countryside; the sixth, that of Warrant Officer Robbie Aitken, failed to open in time and, with his parachute streaming behind him, he struck the ground and was killed.

The above is an account of an actual event—the fiery end of Avro Lancaster LS-H (RAF serial number LM575), one of thousands upon thousands of aircraft that crashed onto European soil during the Second World War. This account comes from the surviving members of her crew, but the colour, the texture, the visual power of that event is pulled from the imagination of a young Polish digital artist by the name of Piotr Forkasiewicz. His nightmarish vision of the final seconds of LS-H’s combat life may in fact be fictionalized, but when it comes to the fate of this particular aircraft, his digital art brings to life the lost terror and depth of personal sacrifice in combat.

The first time I came across the digital art of Forkasiewicz, I felt that, for the first time in my 63 years, I was finally witness, at least visually, to history. In past years, my sense of “the battle in the dark” was from blurry black and white photographs, shot from Bomber Command aircraft using only the light of flares and the fires below. They were powerful, immediate, real... but they exposed very little of the human experience in those deadly skies—a ghostly silhouette, a haze of smoke, an intimation of the inferno ignited below. Through Forkasiewicz’s breathtaking abilities with light and darkness, I can now see back 70 years to those dark nights, last sunsets and happy sunrises when life is renewed yet again.

Until I saw Forkasiewicz’s digital painting called The Last Defender, my visual understanding of what happened in the skies over Europe during Bomber Command night raids came from the minds of traditional artists and rare blurry photographic records. While I applaud the power of traditional art and recognize the immediacy of combat photography such as this shot of an RAF raid on Hamburg, Forkasiewicz’s hyperrealistic images opened a new door to understanding. Photo: RAF

You can see and hear and smell and feel many things when viewing a computer generated (CG) painting by Polish digital artist Piotr Forkasiewicz. His works, almost voyeuristic in detail and immediacy, grip the viewer with overwhelming feelings—feelings that portend doom, surreality that creeps up the back of your neck, relief that floods like a warm sunset, spirituality that opens your mind to the immensity of experience that was the inheritance of the airmen of Bomber Command in the Second World War.

Truthfully, I had been collecting digitally created images of combat and transport aircraft over the past few years with the intention to write a story about the power of imagery created in programs like Microsoft’s FlightSim. These images were wonderful, but really, they were simply happenstance, a moment’s screen capture during a simulated flight. The creative part was in what the Flight Simmers called a “skin”—the texture and markings of an aircraft digitally created and laid over a framework provided by the program. Some were exceptional, others laughable. While detail, proper markings and authentic textures were important to these gamers, the result, though intriguing, could not be called art. Then I came across the work of Piotr Forkasiewicz and a previously unrevealed (to me) world of high performing digital artists in the world known as CG.

Typical of the higher-end of the visual world of flight simulator “skins” is this remarkably beautiful rendition of a Sopwith Pup which I found on the Wings of Honor website. This screen capture was taken during a flight simulation as the gamer flies the Pup skin around in the simulated world. This was the type of images I was collecting for my story on what I thought was “like art”. Screen capture via Wingsofhonor.com

Related Stories

Click on image

Artists like Forkasiewicz and his equally talented colleagues, like Gareth Hector and Marek Rys, were previously unknown to me. I came upon Piotr’s moving digital artwork called The Last Defender while researching imagery for a story on a downed Lancaster which crashed near the small French village of Maisontiers. I was in the process of creating some feeble Photoshopped illustrations to help tell the story when I lit upon the work of Forkasiewicz. Having viewed only a small selection of the artwork produced by the young Pole, I knew right then I would have to ask him for permission to do a story on his work. I found him on Facebook and, after “friending” him, put forth the idea of doing a story on the emerging power of digital art and in particular his own work. I found right then and there that Piotr Forkasiewicz, the artist whose works would occupy even my dreams for the next few nights, was a very humble man. Writing to me, he said, “I don’t think what I do has an artistic value (that is why I would never called myself an artist).” I suppose then it is my purpose to enlighten you, the reader, as to why I believe this is a truly valid and emerging art form and that Forkasiewicz is one of its greatest young artists. Let’s begin by taking a closer look at The Last Defender.

As Lancaster LS-H plummets to its death near the French town of Plaisir, in the digital artwork called The Last Defender, its crew get out of the dying aircraft while they still can. For some reason or another, both of her gunners failed to get out of the aircraft in time to survive, possibly because they were in the direct line of fire from the Junkers. It is likely that her rear gunner died in his turret. Aitken in the mid-upper turret did manage to extricate himself, but it was too late. British Columbia’s Canadian Museum of Flight offered an explanation of the difficulty Aitken would have had to get out: The gunner’s parachute was attached to the fuselage just outside the turret. If he needed to abandon ship, he had to turn the turret to point forwards, open the door, retrieve his parachute, close the door, rotate the turret until it was fully turned to one side, then open the door and fall backwards out of the turret. He then would have to make his way to a hatch and jump. The crew was: Pilot, Squadron Leader Phillip John Lamason DFC RNZAF; Flight Engineer, Flight Lieutenant J. Marpole, RAF; Navigator, Flying Officer K.W. Chapman, RAF; Bomb Aimer, Flying Officer G.A. Musgrove, RCAF; Radio Operator/Gunner, Flying Officer L.H.J. George DFC, RAF; and the two gunners, both killed in the action: Mid-Upper Gunner, Warrant Officer R.B. Aitken, RAF and Rear Gunner, Flying Officer T.W. Dunk, RAF. The others were taken as POWs or evaded capture. The Last Defender by Piotr Forkasiewicz

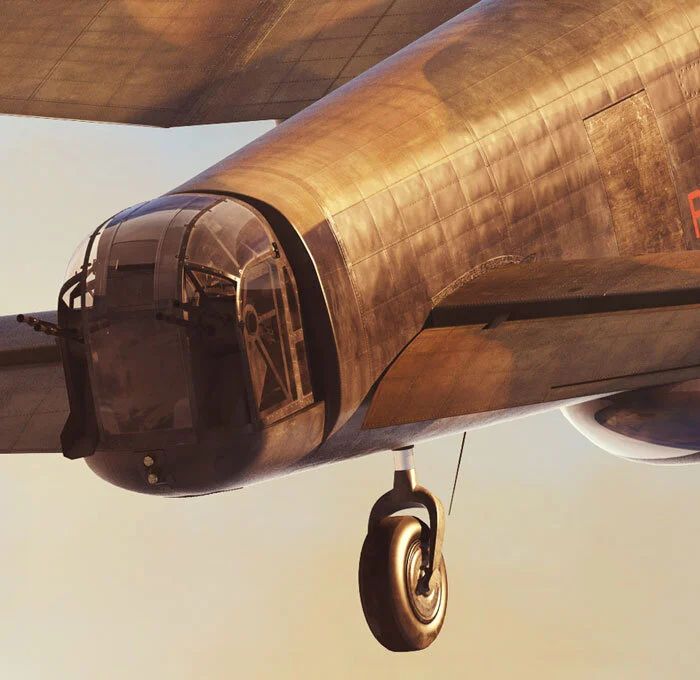

Robbie Aitken’s last stand. A close-up of the astonishing, and frankly terrifying, detail of The Last Defender reveals the faithful accuracy with which Forkasiewicz anoints his artwork. We see the hard rubber tail wheel of the Lancaster with its worn high sides and centre groove, designed as an anti-shimmy device. We also see the polished steel shaft of the hydraulic wheel oleo and a glossy shine of the glass covering of the HS2 navigation radar system blister. This radar may have in fact been the demise of LS-H, as it could be homed in by Luftwaffe night fighters. Detail from The Last Defender by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The flames blow torching from the crippled Number 3 engine are not modelled in the computer, but applied by hand by the artist in the form of layered photographic imagery blended together and representing with frightening sensuality the fuel-fed, slipstream-blown fire that would burn through a Lancaster’s wing in a matter of minutes. The crew of LS-H would have tried to extinguish the fire in the engine, but once it ran away to the wing, it would have been time to bail out of the dying ship. In this image, we see the flaps partially extended, possibly the result of hydraulic failure as well as damage to the right wing from cannon fire from the attacking night fighter. The play of light from the fire on the aircraft’s various surfaces is the most powerful of the artist’s techniques to create his own brand of “hyperrealism”. Detail from The Last Defender by Piotr Forkaziewicz

Pulling back a bit, we see the Mid-Upper Gunner, Warrant Officer R.B. Aitken, in his Fraser Nash turret, blast away with his Twin Browning .303 machine guns, while smoking spent tracer rounds from the attacking night fighter rocket past. Unknown, or perhaps unheeded by Aitken, members of the crew begin to abandon ship, dropping like rag dolls into the night sky. Detail from The Last Defender by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Forkasiewicz does in fact use methods based in techniques used by FlightSim skin designers. He creates a digital framework of whatever he is modelling—from a Lancaster to an architectural interior. Upon this detailed and exactly proportioned map of the object (the Lancaster for instance), he does in fact overlay similar attributes found in a “skin”—colour, protrusions like rivets and access doors, textures, sheen, wear, staining and distress, markings and much more to create a 3-D painting of a Lancaster. This modelled Lanc can be altered to change the markings, the aircraft mark, to adjust the flight control inputs, even to make it appear new or a weathered combat veteran. His model can be rotated in three dimensions and can be viewed from any perspective, and when this is combined with landscape placement, some stunning viewing angles can be achieved, like that of The Last Defender.

After the particularly arduous task of creating and detailing the three dimensional model of the Lancaster, Forkasiewicz embarked upon a lengthy series of studies of this, one of the most important aircraft of the Second World War. Being a mass-produced aircraft (7,377 having been built in various marks), the same model, with altered qualities, could be used to tell a number of the hundreds of thousands of stories that needed to be told about the Lanc and the men who flew them through dangerous and magical skies. Forkasiewicz will tell you he is no expert on the history and production of the Avro Lancaster, though he likely knows more than you and I will ever know. Instead, he relied heavily on the precise expertise of men like Alex Bateman, one of the foremost experts on the Lanc and author of No. 617 “Dambuster” Squadron, and Australian Andrew Macdonald for operational background details.

In his commissioned work called Incoming Threat, Forkasiewicz depicts the moment before the Lamason crew of 15 Squadron’s Lancaster LS-H is attacked by a Junkers Ju88. As they churn through the layers of cloud in the moonlit sky, behind them, the radar-equipped Luftwaffe night fighter closes in out of the clouds using its Lichtenstein radar equipment. Incoming Threat by Piotr Forkasiewicz

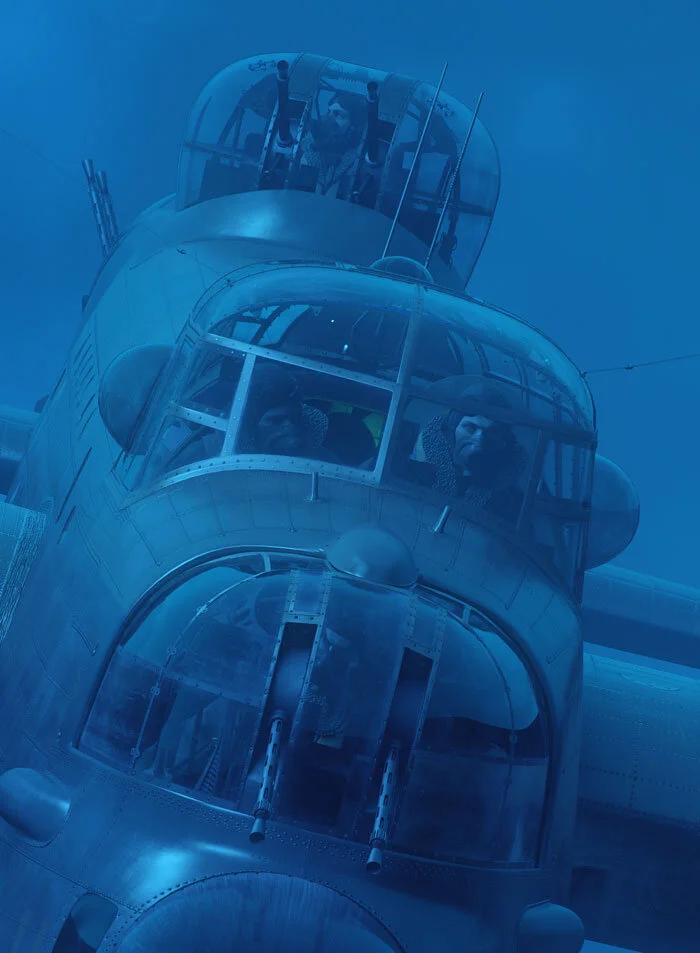

Forkasiewicz’s thirst for detail is astonishing. Not only is every rivet, aluminium joint and formed component perfect in every way, he takes us closer still, right into the cockpit and crew compartment. Here, we see a depiction of Squadron Leader Lamason, the Pilot, a study in concentration, with his eyes ahead, alert for his squadron mates flying close by in the darkness. We see the sheepskin collars of their Irvin flying jackets. Even the pilot’s pupils are dilated, accustomed now to the darkness. Beside him, Marpole, the Flight Engineer, adjusts the throttles on the quadrant to the right of the pilot. Everything is bathed in the luminous blue light of nightfall, but behind them, we see the green glow of Navigator Chapman’s plotting table, eerily warm in the otherwise almost submarine gloom. Detail from Incoming Threat by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Above the fuselage, exposed to the wild and threatening blue night around him, a depiction of Warrant Officer Robbie Aitken scans the darkness for signs of the enemy or the dangerous proximity of other 15 Squadron aircraft. Pupils dilated in the gloom, he looks forward, while as yet unknown to the crew, a threat emerges from the cloud behind them. Detail from Incoming Threat by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Forkasiewicz’s work enables us to see war machines and their crews as one blended unit and from angles never before imagined. In his work, Incoming Threat, we feel the loneliness and determination of a Bomber Command crew. In this view, we see details that truly set Forkasiewicz apart from other digital artists—moisture streams aft over the nose blister glass; the Bomb Aimer, Canadian G.A. Musgrove, can just be seen in the nose turret; and the rough seal where the wing joins the fuselage. Detail from Incoming Threat by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Like a shark rising from the depths of the abyss, a Luftwaffe Junkers Ju88 night fighter, with Lichtenstein radar array, emerges from the cloud, vectored to its prey by radar. The threat posed by this aircraft is enhanced all the more by the lesser detail given this subject. Forkasiewicz could easily have modelled the Ju88 in similar detail, but the mind in reality would see it as a threat, a blur, a dark evil in the night sky, but not a perfectly detailed object. Mere seconds after this, the night sky erupted into a lurid, running gun battle with gunners hosing each other with deadly cannon fire and the darkness blossoming with fire light and death. Detail from Incoming Threat by Piotr Forkasiewicz

When creating his powerfully emotional images of the life of a Lancaster and its crew, computer modelling can go only so far. Presently there is no effective computer algorithms for determining such specific environmental issues like fog, smoke, searchlights, and especially fire. Of this he says, “The elements you’ve pointed are a real challenge every time. This is because of the overall quality of the image I want to have. To create a perfect digital image, all the elements must be done with the same quality and so far the fire and smoke are the elements that I usually create with digital painting or photo mixing, because the 3D tools I use don’t let me achieve convincing effects.” It is in this realm that Forkasiewicz succeeds more than any other. His depiction of flame torching from a holed wing of a Lancaster at night or of the greasy smoke trailing an engine fire only partially under control, injects hypodermics of reality so powerful that the hair on the back of your neck stands up.

Before we get too far into the imagination of Mr. Piotr Forkasiewicz, I should introduce him by way of a photo. In my correspondence with Piotr, I have learned that he is a humble man, one not taken with himself nor guilty of self-promotion. As I have said, he does not believe that what he does is art, but this story I hope will serve to dissuade him of that idea. In a non-digital twist of Forkasiewicz takes his most profound inspiration from such traditional aviation art luminaries as Mark Postlethwaite, who he cites as his “greatest inspiration”. He himself claims to be just a practitioner, not an artist. He said to me, after reviewing the first drafts of this story, that “I don’t deserve for such good things.”

The Google dictionary defines art as “the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.” Since I believe they are beautiful and I am moved to strong emotions, I am therefore drawn to the conclusion that these digital artworks, the product of the imagination of Forkasiewicz, are indeed art. I hope you will agree. If photographers can consider themselves artists for capturing and interpreting reality back to us, and I believe they should, then surely my Polish friend is an artist of the highest calibre.

A self-portrait sketch and photograph reveals a quiet man not comfortable being portrayed. Even in his studio shot, we see only his back as he works. On the wall he proudly displays the powerful legacy of 303 Kosciuszko Squadron—an RAF fighter squadron that was the darling of England during the Battle of Britain. After the war, one of Churchill’s and the Allies’ saddest legacies was to dishonour the sacrifice of the Poles in order not to rile the Soviet Union, who soon ran roughshod over that great nation. The Polish airmen who had given such incredible service to the RAF were prevented from marching in the victory parade in London after the war—to the lasting shame of the RAF. Kosciuszko was also the name of an American-manned squadron during the 1919–21 war with Russian communists, named in honour of Polish General Tadeusz Kosciuszko who came to the aid of George Washington in the American Revolution. To this day, there are towns and counties all over the USA that bear his name—Mississippi, Texas, and Indiana to name a few. In fact, Oprah Winfrey is from Kosciusko, Mississippi. Image via Forkasiewicz

His work extends into many realms including spectacular architectural interiors, motorcycles, and warships. At the end of this story, which focuses completely on his Lancaster projects, you will find a series of dramatic warship images. The world of CG is one of great collaboration, more so possibly than any other artistic field of endeavour. Artists work together on the same projects. Of his warship pieces, Forkasiewicz says: “... I create them in cooperation with my friends who spend months to produce one model. I always create the illustration. My role is to invent the idea of the scene, create the whole scene with sea surface, background, create light and make post-production.” This spirit of collaboration extends everywhere however, and Piotr is quick to mention his Polish compatriots and international colleagues—Gareth Hector, Wiek Luijken, Ronnie Olsthoorn, Robert Perry and Marek Rys. Forkasiewicz’s work has graced the covers of many magazines and been featured in Memorial Flight, the journal of Lincolnshire’s Lancaster Association. He does do commissions, but has never charged for them, preferring only to honour the fallen by creating powerful mementos as gifts for the families of the airmen he wishes so profoundly to honour.

Now, I invite you into the world of Piotr Forkasiewicz. It is a world where you can open with a wide sweeping image of a raging aerial gunfight and then zoom in and in and in until you see the pupils in the eyes of the airmen and feel their fear, their awe, their youth. I invite you also to look, as I did, for the power, the emotions, the lessons, the history, the fear and yes... the art. You will not be disappointed.

Should you wish to order a print of one of the pieces featured in this story or wish to speak with the artist Forkasiewicz via email, he welcomes your correspondence at piotr_forkasiewicz@wp.pl

By Dave O’Malley

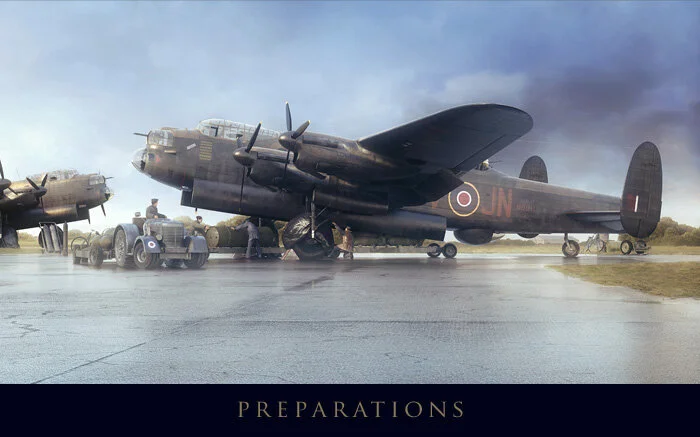

Ake ake kia kaha (“For ever and ever be strong”, the Maori motto of 75 New Zealand Squadron RAF)—Of course, not all of Forkasiewicz’s digital paintings depict moments of desperation and death. In his almost pastoral work, entitled Preparations, the artist tells us volumes about the pre-operation activity and the English weather. Commissioned by members of the families involved, and appearing in Memorial Flight, the journal of Lincolnshire’s Lancaster Association, just this year (2014), Preparations features Lancasters of 75 (New Zealand) Squadron, Royal Air Force “bombing up” at RAF Mepal in Cambridgeshire prior to a daylight raid on Dortmund on 17 November 1944. A winter storm has just blown through, the dark clouds moving off after having dropped heavy rain on the bomber hardstands at Mepal. The crew of Lancaster ND911, the central subject of Preparations, was shot down two days later with the loss of most of the crew: Pilot, Flying Officer P.L. McCarten, RAAF (aged 29); Navigator, Pilot Officer J. Miles, RAF (aged 35); Bomb Aimer, Flying Officer L.A. Martin, RAF (age unknown); Wireless Operator, Flight Sergeant P.F. Smith, RAAF (aged 20); Flight Engineer, Sergeant W.A. Warlow, RAF (aged 30); Mid-Upper Gunner, Sergeant D.G.A. Bryer, RAF (aged 19) and Rear Gunner, Sergeant J. Gray (age unknown and the only survivor). Preparations by Piotr Forkasiewicz

What separates artist Piotr Forkasiewicz from mere mortals in the emerging world of digital art is his studied sense of texture and knowledge of the operational effects on a warhorse like the Lancaster; in particular, the effects of engine heat on the exhaust flame covers, industrial paint coatings and exhaust staining. The light coloured exhaust stains depicted in Preparations is caused by pilots and engineers “leaning out” the fuel mixture (and this increasing the exhaust gas temperature) to save fuel on long operations such as this Lancaster was engaged in. The grey colour is caused by the lead additives in the fuel. Preparations by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Forkasiewicz carefully composes his scene with digitally modelled equipment typical of a bombing up scenario—bomb trolleys, tugs, oxygen cylinders all combine with a wet English landscape to set the scene. Note the purple and white striped Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM) bar next to the 70 mission marks on JN-V’s nose. Preparations by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The artist has faithfully recreated the tarpaulin covers used by the RAF to prevent excessive deterioration of the natural rubber tires through exposure to sunlight as well as protecting the tires from oil drippings. Preparations by Piotr Forkasiewicz

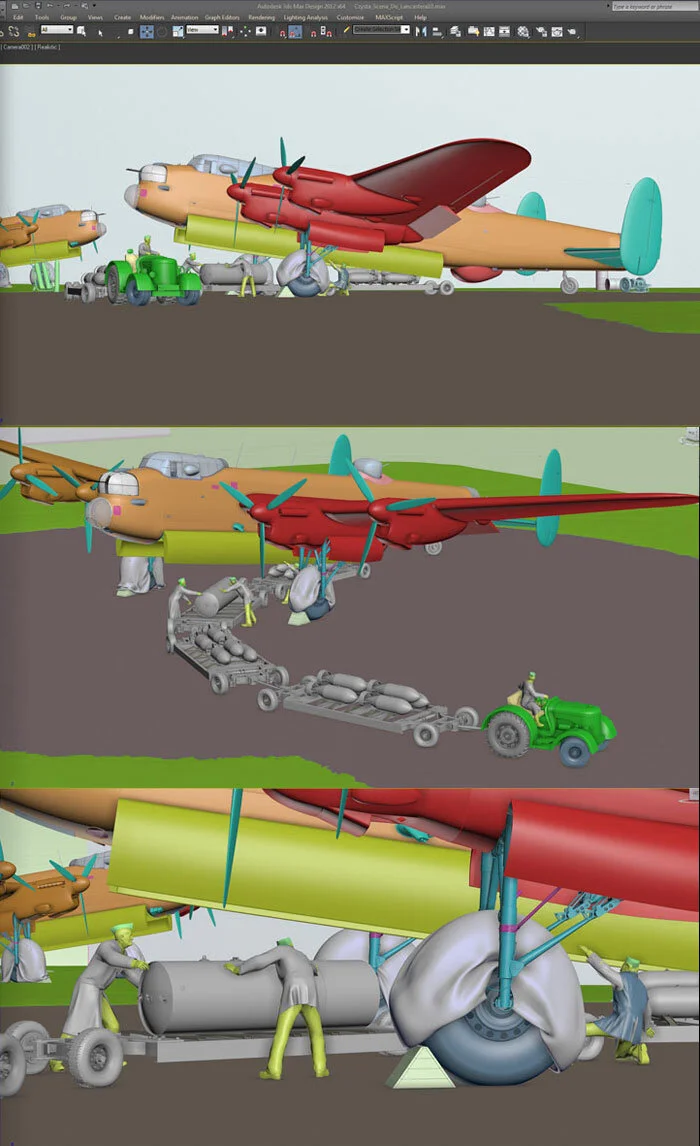

Through a series of five studies, Forkasiewicz determines the eventual structure and composition of the final artwork, from a simple massing model without texture for positioning to tests for weather in November at Mepal to a close approximation of the final work known as Preparations. The bottom study added a Lancaster in the immediate foreground and a Lanc doing a flyover in the far distance. Once looking at this Forkasiewicz could see the overly cluttered nature of the composition and opted for a more simple depiction. Images by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Through a series of five studies, Forkasiewicz determines the eventual structure and composition of the final artwork, from a simple massing model without texture for positioning to tests for weather in November at Mepal to a close approximation of the final work known as Preparations. The bottom study added a Lancaster in the immediate foreground and a Lanc doing a flyover in the far distance. Once looking at this Forkasiewicz could see the overly cluttered nature of the composition and opted for a more simple depiction. Images by Piotr Forkasiewicz

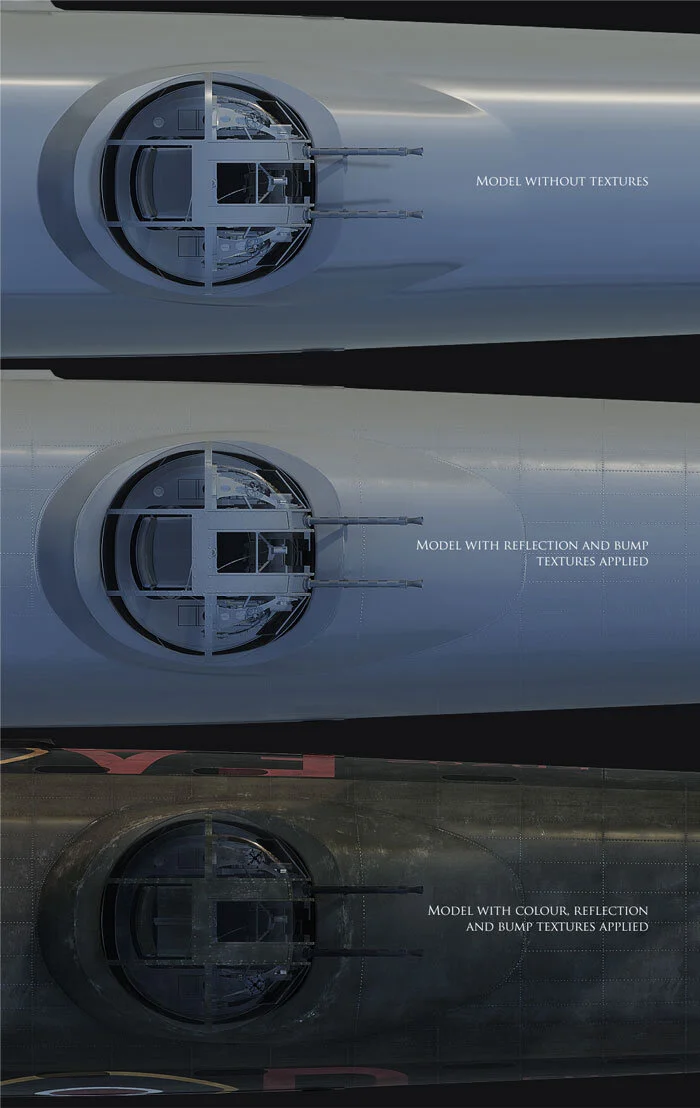

Though perhaps these three images make an oversimplification of the process, it demonstrates the complexities and detailed work employed by Forkasiewicz to create his emotional artwork from an underlying mathematical computation. To view more of the artist’s process visit the CG Society Website. Details of mid-upper gun by Piotr Forkasiewicz

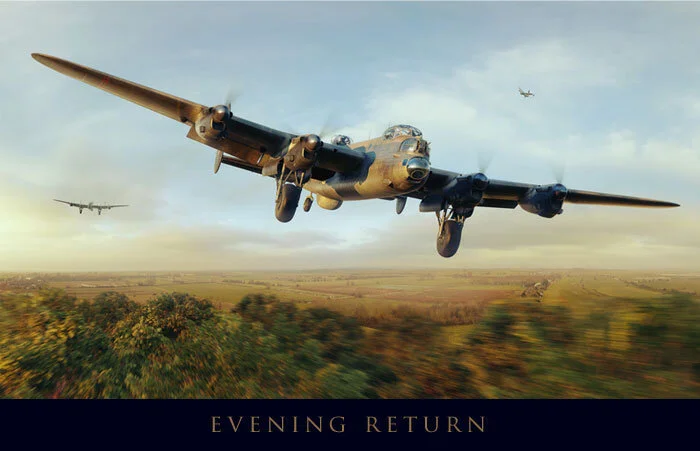

The digital artwork entitled Evening Return portrays the same Lancaster (JN-V) as in the previous sequence, but at a happier time, long before her demise in mid-November of 1944. It’s a summer evening and the sun is low in the horizon, casting horizontal shadows from the starboard wing. JN-V sets up for final at RAF Mepal and skims the treetops in a joyous return, while other 75 Squadron Lancs settle in stream. The low and golden light quality transforms the Lancaster into warm tones, compared to the colder hues of the work known as Preparations. Forkasiewicz is always aware of every detail and nuance in lighting that will bring both credibility and mood to his work. Evening Return by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Flaps, doors, oleos... all are made real by weathering, staining and paint wear. This piece was commissioned by a member of one of the families of the crew and appeared along with five other pieces in Memorial Flight, the journal of Lincolnshire’s Lancaster Association. Detail from Evening Return by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Though the detail in this close-up is flawless, it is the perfect image of the landscape ahead reflected in the nose blister that truly draws one’s breath—with a setting sun in the correct location for the lighting. Detail from Evening Return by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Through speed blurring, Forkasiewicz creates a strong sense of motion, which is always more evident at lower altitudes. Detail from Evening Return by Piotr Forkasiewicz

In the commissioned work Final Route, a large formation of Lancasters from 156 Squadron, Royal Air Force, fly steadfastly through heavy flak as they approach Hamburg, Germany. The scene is late in the war, when the Royal Air Force took on more daylight raids deep into Germany. The scene depicts Lancaster GT-O (PB517) staying the course through the box of flak, while ahead, one of 156 Squadron’s other Lancs takes hit in her Number 1 engine. To the north (in the upper left) we can see the contrails of enemy fighters as they begin to engage the bomber stream. Final Route, by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The Lancasters of 156 Squadron RAF, a Pathfinder unit, took off from RAF Upwood at 0630 on the morning of 31 March 1944, arriving over Germany in slanting golden morning light—so gorgeously portrayed by Forkasiewicz. Note the extra wear on the crew door behind the RAF serial. Detail from Final Route, by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Forkasiewicz’s obsession for detail in every rivet, inspection panel and correct textures leads to a vision of exceptional clarity and power, in even the most mundane of details within each composition. Final Route, by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The Flight Engineer of GT-O looks with great concern up and to his right. Intelligence reports from the raid seem to indicate that Messerschmitt Me 262 jets tore through the formation and it is possible that the aircraft, which was lost on this raid, was the victim of the Luftwaffe’s highly capable twin-engined jet fighter. Lancaster GT-O ultimately came down over Stemmen, near the city of Rotenburg. Detail from Final Route, by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The hyperrealistic quality of Forkasiewicz’s vision creates a sense of reality that is both captivating and disturbing... in every detail. Detail from Final Route, by Piotr Forkasiewicz

In a detail from Final Route, Forkasiewicz depicts a distant Lancaster beginning a long slide from her place in the bomber stream as her crew battles a fire in her port outer or Number 1 Merlin engine. On this mission to bomb Hamburg, 156 lost two Lancasters, the third and second last losses of the war for the squadron. In addition to the featured Lancaster PB517, the unit lost Lancaster GT-B (PB468). The aircraft came down 4 miles from the Hamburg aerodrome, with all seven aboard killed. Detail from Final Route, by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The bulk of Bomber Command’s 392,137 combat sorties were executed in the dark of night. While this, on the surface, may have seemed like a cloak of invisibility, the Command’s losses were higher than any other Allied service of the war. The cloak of invisibility went both ways, with Luftwaffe night fighters closing in unseen through cloud and on moonless nights, and with hundreds of bombers crowding into the same bomb run, collisions were commonplace. In Forkasiewicz’s In God’s Keeping, a commissioned piece, we sense that these young professionals, flying these dangerous missions, have done all they can to prepare, and now are in God’s hands as they press towards the target. In the particular case of this Lancaster, PM-M (LM173) of 103 Squadron RAF, that fate would be delivered during this night raid to the synthetic oil plant at Sterkrade, in Northern Germany on 17 June 1944. LM173 had only seven hours on the airframe when it was lost. The normal weathering and staining which would be evident in a veteran aircraft was reduced to depict a factory fresh Lancaster. In God’s Keeping by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Soft moonlight plays on the engines and wings of Lancaster PM-M. The aircraft is pictured flying over the North Sea in scattered cloud with starlight twinkling, having left their base at RAF Elsham-Woods near midnight on the 16th. Forkasiewicz’s sense of light and texture elicits a quiet sense of doom and determination as the aircraft joins 320 other Bomber Command aircraft (Lancasters, Mosquitoes and Halifaxes) for the mission. On the night of her death, M-Mother carried in her arms 7 men whose lives were soon extinguished over the North Sea—Pilot, Pilot Officer Maurice Lambert, RNZAF (aged 28); Flight Engineer, Sergeant David Whamond, RAF (aged 22); Navigator, Sergeant Douglas Lawler, RAF (aged 24); Bomb Aimer, Sergeant George Ware, RAFVR (aged 21); Wireless Operator/Air Gunner, Sergeant John McGinn, RAFVR (aged 23); Mid-Upper Gunner, Sergeant Frederick Hardy, RAF (age unknown); Tail Gunner, Sergeant Roland Fitchett, RAFVR (aged 21). Whilst scanning the internet for information about the demise of PM-M (LM173), I came across Bomb Aimer Ware’s logbook for sale on Ebay. The seller was asking £320 for the artifact, which did not sell. Detail from In God’s Keeping by Piotr Forkasiewicz

One can only imagine the memories of starlit nights, ghostly clouds and crowded skies that aircrew of Bomber Command aircrew took home with them if they survived. Here, a depiction of Mid-Upper Gunner, Sergeant Frederick Ralph Hardy speaks to the surreality of the experience—the accompanying bomber stream, rising and falling on the air currents, clouds moving off to reveal stars rising, lighting the way to danger. Sadly, this night, gunner Hardy and his entire crew were killed when they were shot down over Holland en route. Detail from In God’s Keeping by Piotr Forkasiewicz

One can only imagine the feelings of loneliness, dread and awe coursing through a tail gunner’s mind as he looks back at the trailing bomber stream. The men in the front can speak to each other and have each other for comfort. Both the mid-upper and tail gunner would spend the dangerous hours of their mission in freezing cold solitude, wrapped mostly in their own thoughts of home, loved ones and their own mortality. The Latin motto of 103 Squadron, “Noli me tangere” means “Touch me not.” On 17 July 1944, they were sadly touched by the hand of death, somewhere over the North Sea. Detail from In God’s Keeping by Piotr Forkasiewicz

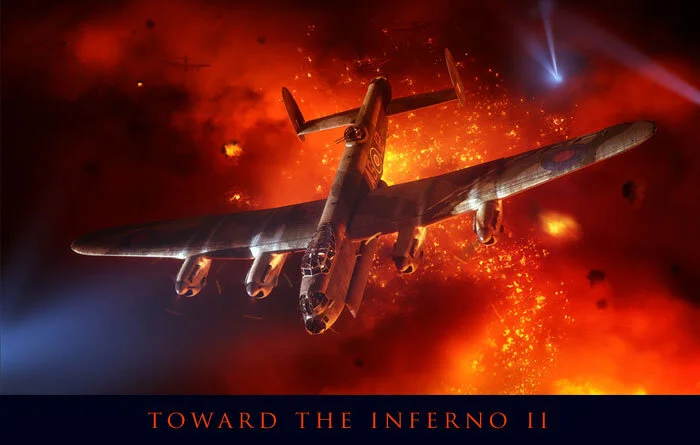

Forkasiewicz’s composition entitled Toward the Inferno depicts 166 Squadron RAF Lancaster AS-J2 (LL749), driving through flak and searchlights, having dropped her payload on the German city in the central Ruhr valley. The digital painting depicts the RAF Kirmington-based LL749 on the night she was lost. 166 Squadron lived by their motto: “Tenacity” and in particular, the crews of the hard luck aircraft coded AS-J2. On 27 March 1944, Lancaster AS-J2 (LL749), pictured above, was lost over Essen. One month later, on 27 April 1944, her replacement, Lancaster AS-J2 (ND825), was shot down over Friedrichshafen. On the night of 5 May 1944, Lancaster ME806 was also lost over Pauillac, France. On 2 February 1945, Lancaster AS-J2 (ME648) was lost over Bruchsal, Germany and then a few weeks later, AS-J2 (PB153). In addition, the squadron also operated Lancasters with code AS-J—losing a number with that aircraft code, including ME647 and DV220. Toward the Inferno by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The blue light of searchlights and the yellow fires below combine in an eerie green light, as we gaze downward, past the Number 2 engine of AS-J2. The beams of searchlights and their effects on smoke and cloud present many problems to a digital artist looking to accurately portray a scene over a burning city. Forkasiewicz is careful to allow certain details, such as searchlight beams and other aircraft in the formation, to remain secondary to the central image. Detail from Toward the Inferno by Piotr Forkasiewicz

A close-up of the nose of AS-J2 focuses on her Bomb Aimer, Sergeant A.G. Coney, the only survivor from the loss of the aircraft, as, lit by the lights below, he opens the bomb doors and gets set to drop his bomb load. Detail from Toward the Inferno by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Combining the ghostly blue from searchlights on the left with the raging inferno of Essen below, an apocalyptic hue is created, moving the scene into the realm of the surreal. Under the aircraft code AS-J2, some 35 men lost their lives or became POWs. On this night, the men included Pilot, Flight Sergeant V.L. Perry; Flight Engineer, J.J. McInroy; Bomb Aimer, Sergeant A.G. Coney; Navigator, Flight Sergeant L.V. Woodfield; Wireless operator/Gunner, Flight Sergeant M.D. Williams; Mid-Upper Gunner, Sergeant A.W. Gowland; Rear Gunner, Sergeant W. Harris. Detail from Toward the Inferno by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Forcasiewicz created two separate visions of the 166 Squadron attack on the Ruhr city of Essen and Lancaster AS-J2. This one relies mostly on the raging fires below to light the scene, but the Lanc and the Perry crew are still coned by a searchlight from the left as they turn in that direction. Toward the Inferno II by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Turning to starboard, immediately following the release of the bomb load (seen falling between the two port engines), Flight Sergeant Perry and his crew are caught in the glare of a German searchlight. Detail from Toward the Inferno II by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Perry turns to starboard and is immediately blinded by a searchlight beam, while Engineer McInroy shoves the throttles forward to gain speed. It’s details like the streaking of moisture and dirt on the blister glass and the rivet work which really make Forkasiewicz’s efforts come to life. Detail from Toward the Inferno II by Piotr Forkasiewicz

In 1940, following the London Blitz, the commander of Bomber Command, Arthur “Bomber” Harris said: “The Nazis entered this war under the rather childish delusion that they were going to bomb everybody else, and nobody was going to bomb them. At Rotterdam, London, Warsaw, and half a hundred other places, they put that rather naive theory into operation. They sowed the wind, and now, they are going to reap the whirlwind.” In Toward the Inferno II, Forkasiewicz portrays that harvest in frightening detail. Detail from Toward the Inferno II by Piotr Forkasiewicz

As the doomed bomber AS-J2 departs Essen, her Rear Gunner, Sergeant Harris, is afforded a surreal and frightening view of hell unleashed. Detail from Toward the Inferno II by Piotr Forkasiewicz

One of the most dramatic of Forkasiewicz’s works is Into the Darkness, a powerful depiction of an attack on the largely Canadian crew of Lancaster BH-U “Uncle” (LM178), a 300 Squadron Lanc brought down by a Junkers Ju88 night fighter over the French city of Orléans on the night of 24–25 July 1944. The crew for this mission were Pilot, Pilot Officer William Robinson, RCAF; Flight Engineer, Sergeant Ernest Morter, RAF; Bomb Aimer, Flying Officer James Duguid, RCAF; Navigator, Flying Officer C.M. “Jo” Forman, RCAF; Wireless Operator/Air Gunner, Sergeant Leslie Page, RAF; Mid-Upper Gunner, Sergeant James Rheubottom, RCAF and Rear Gunner, Sergeant Samuel Dunseith, RCAF. Into the Darkness by Piotr Forkasiewicz

It doesn’t get any more dramatic than this detail. The starboard wing takes heavy hits from the night fighter’s cannon and bursts into a blowtorch of burning fuel and begins its rapid collapse. We see Flight Engineer Morter, craning his head in disbelief as the wing breaks apart before his very eyes. The light work in this particular piece is nothing short of astonishing. Detail from Into the Darkness by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The magic lies in the details—shot away engine cowl, damaged radiator and a Merlin beginning to lose power. Detail from Into the Darkness by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The artist leaves no detail forgotten. The damaged No. 3 Merlin, losing power, begins to slow down as evidenced by the blur of the propeller blades—in sharper view than the undamaged No. 4 engine. The heavy blows from the night fighter have not only ruptured the fuel tanks and set fire to the issuing gas, they have broken the structure of the wing itself and the outer wing and engine begin to fold as the Lancaster rides quickly to her doom. Detail from Into the Darkness by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Lancaster BH-U, nicknamed Luck of the Irish, took off from RAF Faldingworth at 2037 on the night of 24 July 1944, headed for Stuttgard. There were three survivors of the battle between LM178 and the Ju88 night fighter—Dunseith the Rear Gunner, Forman the Navigator and . They were over Orléans when they were set upon by the Junkers at around 0015 in the morning. One of the crew who had a ringside seat to the gun battle was Rear Gunner Sam Dunseith. In a recent letter to an online forum called ww2f, an acquaintance of Dunseith, with the online name Big Daddy, produced a written account of the last moments from Dunseith’s perspective. In part, it reads: The narrative is mine but all elements are based on firsthand interviews and RAF Loss Reports filed in Aug 44... The Lancaster was raked along the fuselage and right wing with 30mm cannon and machine gun fire, smashing the upper turret and setting the wing ablaze. F/O W. Robinson, the pilot, ordered them to bail out.

Sam had managed to briefly return fire before his turret was disabled and he was slightly wounded. Being rotated to starboard and then disabled, the turret doorway was almost impassable but he was just able to squeeze back into the fuselage, activating his Mae West in the process. When he grabbed his parachute and opened the double doors over the rear wing spar, he was met with a frightening sight. The photo-flash had been ignited in the attack and the interior of the aircraft was burning furiously, half of the bomb bay already being burned away. His friend and mid-upper gunner, 17-year-old Jimmy Rheubottom was hanging dead in his turret. Sam pulled open the rear door and jumped out into the burning slipstream, only to have the door slam shut on his foot and leave him hanging by one leg. As he wiggled out of his flying boot and fell away from the aircraft, the starboard wing exploded. In the front of the Lanc, F/O Joe Forman was just handing pilot Robinson his parachute. They were both blown clear of the aircraft as it exploded.

Meanwhile, Sam was continuing to have his own problems. As he fell away from the burning bomber, he pulled the handle on his parachute. It came off in his hand. He looked down to discover that the front of his chute was on fire. Beating out the flames with his hands, he reached into the chute pack, found the ripcord string and pulled it. Amazingly, his chute opened. Even more incredibly, Sam and Joe Forman landed only a few feet from each other in the same field. Only they and F/O Robinson escaped the burning aircraft.

For more from these remarkable amateur historians on the ww2f.com forum, click here. Detail from Into the Darkness by Piotr Forkasiewicz

So young. Many young airmen, like Canadian Jimmy Rheubottom, lied about their age to become airmen and test their metal in combat. At the time of his death, Rheubottom, the mid-upper gunner, was just 17. He could not have been older than 16 when he enlisted in the RCAF. Here we see cannon fire from the night fighter striking Rheubottom in his turret and raking the starboard side of the Lancaster. Detail from Into the Darkness by Piotr Forkasiewicz

From the hopeless to the hopeful, not all of Forkasiewicz’s artworks depict the final and dramatic moments of a Lancaster. In Helping Hand, two Lancasters of 156 Squadron thunder low, past the Dutch coast and on over the North Sea. The lead Lancaster GT-P (ND422) is in trouble with the No. 3 engine smoking and its propeller feathered, while he struggles to get home to RAF Upwood. The crew list for ND422 for the Kleve Raid includes Pilot, Flight Lieutenant Anthony Pope, DFC, RAF; Flight Engineer, Sergeant Gerald Batten, RAF; First Navigator, Flight Lieutenant Lorne Munro, DFC, RCAF; Second Navigator (it was a Pathfinder Squadron), Pilot Officer Edgar Marlow, RAF; Wireless Operator, Sergeant Kenneth Antcliffe, RAF; Mid-Upper Gunner, Pilot Officer Ivan Kelly, RCAF and Rear Gunner, Pilot Officer Robert Fletcher, RCAF. Helping Hand by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Black sooty smoke emanates from the damaged and feathered No. 3 engine. The story of a 156 Squadron Lancaster returning on three engines from a raid on Kleve is correct, but information contained on the 156 Squadron history website indicates that, while Pope’s crew was part of this raid, it was the squadron CO, Wing Commander Bingham-Hall’s aircraft (PB507) that was hit in one of its engines and forced to fly home on three engines after completing its Master Bomber duties as a Pathfinder leader. The website also indicates that it was the port inner engine and that the aircraft returned unaccompanied. All this being said, it is still possible that this happened to Pope in the manner it is portrayed and regardless, the image is a masterpiece in my mind. Detail from Helping Hand by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The Flight Engineer looks back to find the shepherding Lancaster while the pilot anxiously watches the still smoking engine. The Lancaster displays an astonishing 72 completed sortie markings on her fuselage, and commensurate wear on her wings. Detail from Helping Hand by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Behind GT-P, another Lanc from the 90 aircraft-strong raid (Lancasters and Halifaxes) holds station on GT-P’s starboard wing lending morale support mostly as there would be little they could do except vector a fast boat to the scene of a ditching should it happen. The squadron code on the fuselage can only be CF, CE, GF or GE. This means that the only squadron that this could be would be 625 Squadron, the only Lancaster unit of the four possible squadrons. Some information I found on the ww2aircrfat.net forum website indicates that on the night of 7 October 1944, 625 Squadron was part of another raid on Emmerich, Germany which is located only a few kilometres from Kleve on the other side of the Rhine River. It all seems to fit. Detail from Helping Hand by Piotr Forkasiewicz

This work was an unnamed artwork by Forkasiewicz, so the author has given it a working title—Bomber Stream. It depicts Lancaster LE-L (ND335) of 630 Squadron as seen from the cockpit of another 630 Lanc and about to drop its bomb load on targets in the city of Nuremberg. In this image we see the cockpit framework and the hazing of the Perspex canopy. Bomber Stream by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Looking up into the bomb bay of L-Love, we see she is “loaded for bear”—with an industrial demolition load of 14 1,000-pound MC (medium capacity) high-explosive bombs and a 4,000-pound “cookie” or blockbuster bomb. Given the fact that the load is about to be released, it could be considered that these two Lancs are perhaps uncomfortably close! Detail from Bomber Stream by Piotr Forkasiewicz

A close-up of the “cookie” and her 14 little sisters. The 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) cookie was regarded as a particularly dangerous load to carry. Due to the airflow over the detonating pistols fitted in the nose, it would often explode even if dropped, i.e. jettisoned, in a supposedly “safe” unarmed state. Safety height above ground for dropping the 4,000 lb “cookie” was 6,000 ft; any lower and the dropping aircraft risked being damaged by the explosion. Info via Wikipedia; Detail from Bomber Stream by Piotr Forkasiewicz

A nice detail of the staining and streaking aft of the Merlin. Detail from Bomber Stream by Piotr Forkasiewicz

One of Forkasiewicz’s, and in fact any digital artist’s, formidable tools is the ability to put the viewer in any spot to watch the action. In the previous piece, we took the vantage point of the pilot getting uncomfortably close to a bomber as she is about to drop her load. Here, we take the particularly voyeuristic view of the lonely rear gunner watching with dread as seven of his friends struggle to get out of a burning Lancaster over Nuremberg on the night of 30–31 March 1944. No detail is left uninvestigated... even the crazing of the rounded Perspex turret in the upper left corner. The focus is on the middle ground Lancaster, while the dying Lanc seems to drop into the scene. Nuremberg by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The artist’s technique for and ability with depicting fire is second to none. Most of his paintings have a grim, tragic reality to them, both dreamy and apocalyptic at the same time. This is largely the result of Bomber Command Lancasters being deployed mostly at night. Detail from Nuremberg by Piotr Forkasiewicz

One can read a lot from each of Forkasiewicz’s digital paintings. As the Lancaster rolls to port to its death, the Lanc in the lower right banks to the left as well to clear out of its path. Detail from Nuremberg by Piotr Forkasiewicz

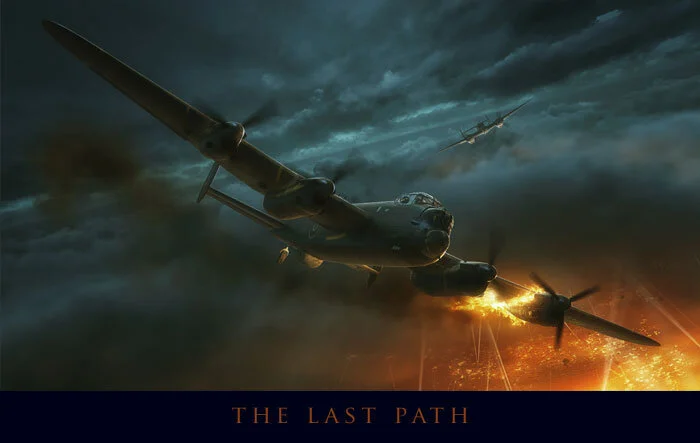

In this dramatic encounter over Mannheim on 23 September 1943, Lancaster OF-P (JA708) of 97 Squadron RAF is set on fire by an attacking Messerschmitt Bf110 night fighter. Flying out of RAF Bourne in Lincolnshire, the aircraft was brought down with three killed. It is interesting to note that it is frequently the case that with a Lancaster brought down by a rear attacking night fighter, the two gunners fail to make it out of the aircraft—either dead or wounded in the gunfight, or unable to extract themselves from their positions. On this fateful night over Mannheim, the crew of OF-P was: Pilot, Flight Lieutenant Robert Fletcher, RAFVR (POW, age unknown); Flight Engineer, Flight Sergeant Joe Nelson, RAFVR (POW, age unknown); Navigator, Squadron Leader Kenneth Foster, DFC and Bar, RAFVR (Killed, aged 26); Bomb Aimer, Flight Sergeant Jack Beesley, RAFVR (POW, age unknown); Wireless Operator/Gunner, Pilot Officer Wally Layne, RAFVR (POW, age unknown); Mid-Upper Gunner, Squadron Leader Robert McKinna, DFC and Bar, RAFVR (Killed, aged 33); and Rear Gunner, Flight Sergeant Henry Page, RAFVR (Killed, aged 20). It is interesting to note that the navigator was a Squadron Leader as well as the mid-upper gunner—both with two DFCs. This makes sense for the nav, as this was a Pathfinder Squadron and the navigators were the most experienced in the RAF. It is rare indeed to find a gunner as a Squadron Leader with two DFC ribbons on his uniform, rare indeed. Detail from The Last Path by Piotr Forkasiewicz

A close-up of the rich colours of the play of light on the cockpit area. Detail from The Last Path by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The digital art community, brought up in the shareware world of social media and web discussion forums, is an open community in many ways and sharing of work is a common occurrence. Here, the attacking Messerschmitt Bf110 night fighter is actually the work of Gareth Hector, a CG colleague of i. In the digital world, a file is simply transferred and the rendering is inserted into the scene, taking on the lighting conditions and attributes determined by the artist Forkasiewicz. To see more of Gareth Hector’s equally amazing work, visit GarethHector.co.uk. Detail from The Last Path by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The light of the engine fire illuminates the wear and staining on the tail wheel and HS-R radome. Detail from The Last Path by Piotr Forkasiewicz

There is not much one can add to this spectacular image of a dying engine, a dying city below, and searchlights probing the night sky. Detail from The Last Path by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Some of Forkasiewicz’s works have a powerful surreal, even submarine quality to them and they lead one to think about the visions that would burn into the memories of aircrew who witnessed these images. We tend to think of night raids as thundering aircraft in total blackness save for the fires they have started, but a sortie would in fact present a series of very powerful visual stimuli such as flying through a rain of flares over Nuremberg. On this night, the Germans tried a new technique by dropping numerous flares to light the bomber stream as it headed towards the target. This piece is of no specific aircraft and it was published in Memorial Flight, the journal of Lincolnshire’s Lancaster Association in 2014. Flare Rain by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Homing in on the Pathfinder flares, the Lancaster crews enter a world of uncertainty marked for them by the RAF’s best navigators. Detail from Flare Rain by Piotr Forkasiewicz

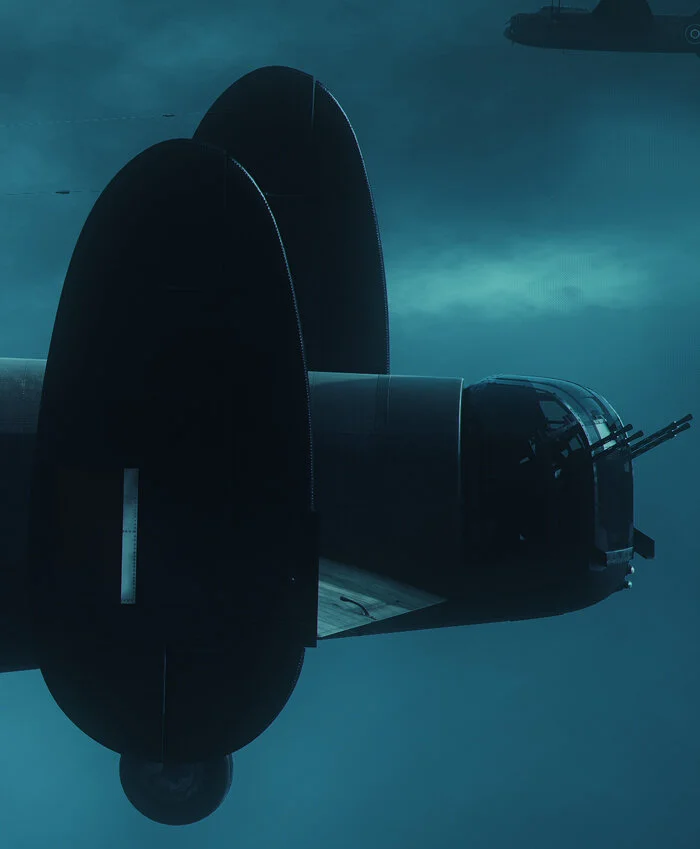

Looking for all the world like a U-boat slipping through some aquatic murk, populated by phosphorescent and ancient jellyfish, Forkasiewicz has created a terrifying beauty, perhaps one from an alien world. But on contemplation, one realizes that surreality, alienation, apocalypse, danger, loss and the silence of loneliness in a thundering world were the travelling companions of Bomber Command aircrew on the long and dark nights of the Second World War. The artist has allowed us just a glimpse of the insanity and the beauty. Detail from Flare Rain by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Even the distant flares are modelled to perfection. Detail from Flare Rain by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Wheels down, flaps lowered, power coming down, a Lancaster comes home over England. Forkasiewicz uses real photographs of rural settings and urban streets in his works, relighting them and sampling details from other sources to create a reality from constituent parts. Heading - Sunset by Piotr Forkasiewicz

This digital artwork was commissioned for the cover of a military magazine. As with all of Forcasiewicz’s works, I love to dive in and look around, searching for new details that amaze. In this case, I was first drawn to the face of the Lanc’s pilot, as he sits up high for a look over the nose towards his home airfield. The wear on the aircraft’s wings and the sunset reflected in the nose blister draw one in. Detail from Heading - Sunset by Piotr Forkasiewicz

625 Squadron Lancaster CF-H, (LM512) slips through cloud alone over the Rhine River valley on a moonlit night. LM512 and its 8-man crew were lost on a mission to Frankfurt on the night of 12–13 September 1944. It was not clear in after action reports if it had been taken down by flak or in a collision with another Lanc. Various records noted on the internet also claim that its aircraft code was actually CF-M or CF-N. Over the Rhine by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The crew of LM512 banks left towards an oxbow in the Rhine River, a valley of incredible danger for the crew of a Lancaster bomber. The 8-man crew, one larger than the normal complement was what the RAF called a “Second Dickey” flight. On a “Second Dickey” flight, a rookie pilot arriving on squadron with his new crew, would make his first flight as a Second Pilot with an experienced crew to see how they operate and to get blooded, while his crew stayed behind. LM512 was lost on the Frankfurt raid, the crew was made up of: Pilot, Flying Officer Howard Cornish, RAAF (aged 21); Second Pilot, David Tointon, RCAF (aged 21); Flight Engineer, Sergeant Charles Ross, RAFVR (aged 37); Navigator, Flight Sergeant Richard Askie, RAFVR (aged 20); Bomb Aimer, Sergeant Ronald Evans, RAFVR (aged 21); Wireless Operator/Air Gunner, Flight Sergeant James Douglas, RAAF (aged 20); Air Gunner Sergeant Robert Barker, RAFVR (age unknown); Air Gunner, Sergeant Arthur O’Connor, RAFVR (age unknown). Detail from Over the Rhine by Piotr Forkasiewicz

A haunting detail from Over the Rhine offers up an image of a ghostly wraith, blue flame and lead streaming from her engines. Detail from Over the Rhine by Piotr Forkasiewicz

The artist is always challenging himself with new lighting and weather situations. Here, a Lancaster disappears into heavy cloud on a wet day. Through Clouds by Piotr Forkasiewicz

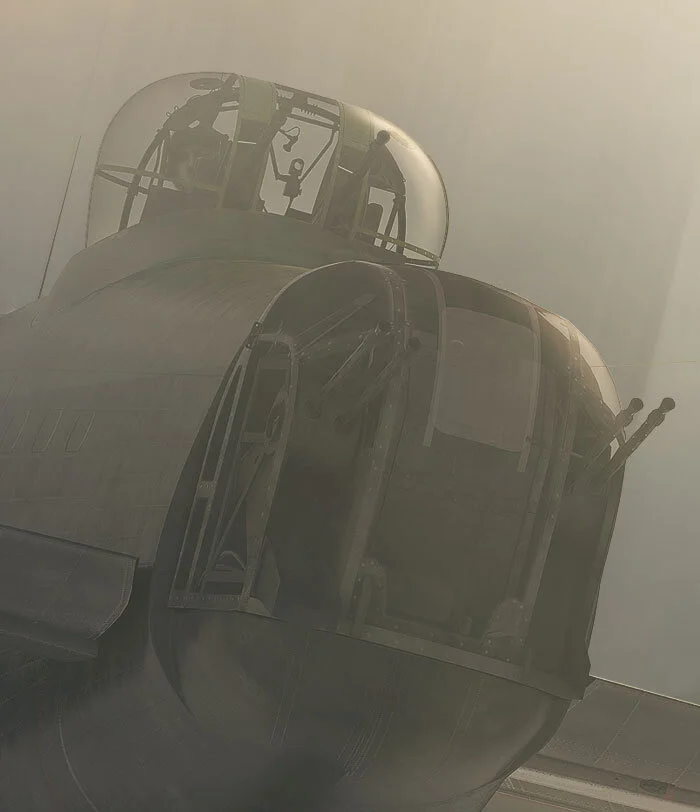

Digitally-based art allows the artist to move his model in space and find perspectives that speak to the scenario. Here, the big bomber slides into the safety of the mists, seemingly glistening with moisture. The compression of space and foreshortening of objects in perspective helps us to see a classic warhorse in new ways. Detail from Through Clouds by Piotr Forkasiewicz

For now, the mid-upper gunner can relax a bit as he and his fellow crew slip into the protection of the clouds. Still, he appears worried. Detail from Through Clouds by Piotr Forkasiewicz

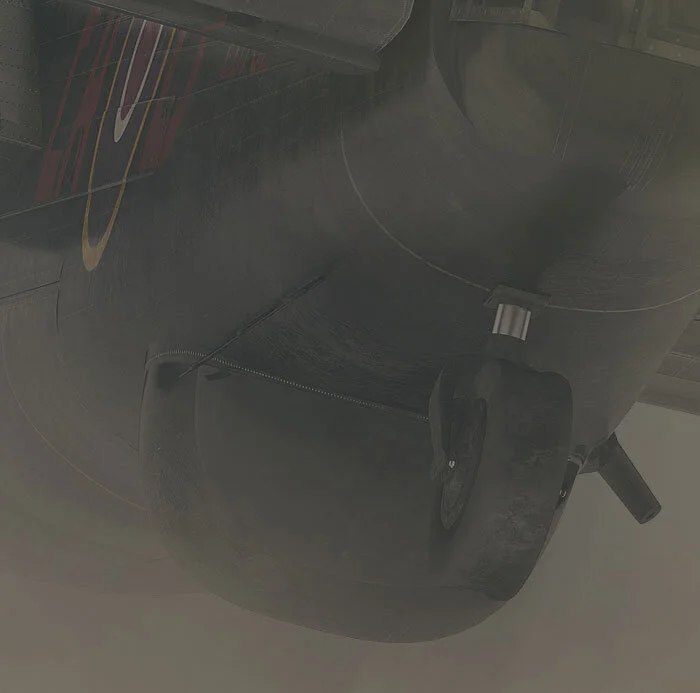

Note the wear on the anti-shimmy tire and the bead of rivets running round the HS-R blister. Detail from Through Clouds by Piotr Forkasiewicz

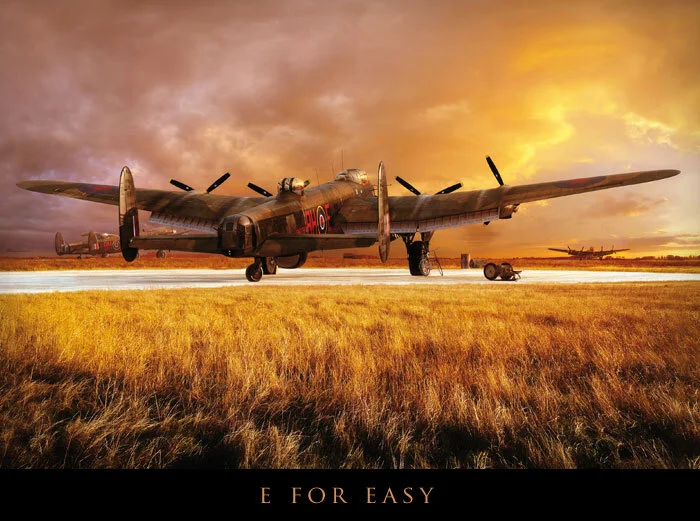

In this bucolic scene we look over a field of fescue, golden in the sunset at possibly RAF Faldingworth, the last airfield occupied by the Mazowiecki—the men of the Land of Masovia bomber squadron. No other group of aviators symbolized courage more than the romantic Poles. Their country had already been swallowed up by the Nazis, but they fought tooth and nail alongside Great Britain and airmen from the Commonwealth to bring an end to the tyranny they knew so well and to stop it from reaching England. Yet... when the war ended, their massive contribution was swept under the carpet by Churchill and other Allied leaders to appease Stalin who wanted all that Poland had to offer. They were not even allowed to march in the victory parade down the avenues of London after the war for fear of angering the Soviet dictator Stalin. Truly one of the more dishonourable political moves of the postwar era. When Forkasiewicz finished this work, he gave a print of it to the still-living bomb aimer from E for Easy, Major Czeslaw Blicharski. E for Easy by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Light has the power to bring forth emotion. The dark foreboding blues and greens from previous works evoke strong emotions of fear, doom and unease, but the golden light at the end of another day speaks to warmth, hope and a return to normalcy. Detail from E for Easy by Piotr Forkasiewicz

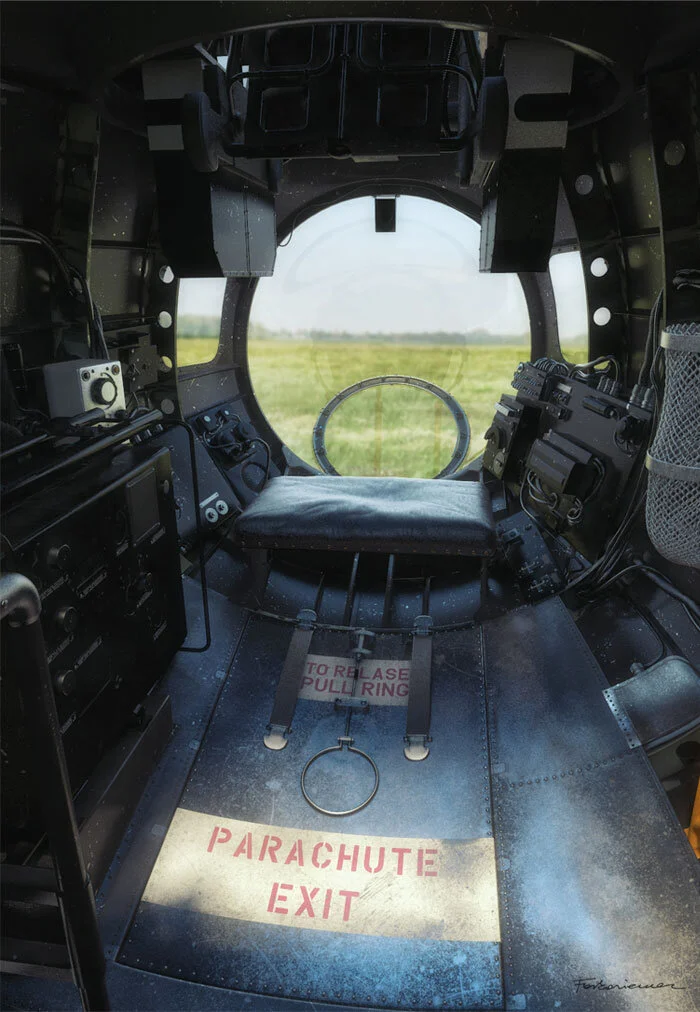

Forkasiewicz’s Lancaster interiors are a tour de force, combining weathering and a clarity that allows us to see and feel the spaces that carried the aviators on their operations in a way that even a photograph cannot do. Here we see the spot where the bomb aimer would lie down to work the bomb sight. Above we see the bottom of the seat where the bomb aimer would sit in to man the forward turret. Interior by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Leather, steel, Bakelite and canvas—there is no texture which Piotr does not nail perfectly. Interior by Piotr Forkasiewicz

From the point of view of the flight engineer, whose responsibilities focused on the throttles and dials during takeoff and landing, we can look down into the bomb aimer’s compartment. Interior image by Piotr Forkasiewicz.

Forkasiewicz is not a one dimensional, one subject artist. This story is focused on his works of Lancasters, but he also visualizes works of naval ships, architecture and conveyances of transportation in general, his particular passion. Here he combines aviation with his love of mighty warships in a depiction of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s aircraft carrier Taiho, with Mitsubishi Zeros forming up to attack the enemy. It was at just such a moment as this that she was caught in the crosshairs of the periscope of USS Albacore, a fleet submarine of the US Navy. Of the six torpedoes launched against her, four missed, one was dived upon by an aircraft from the carrier (it literally crashed into it) and detonated, but the sixth struck her starboard side, leading eventually to her sinking, with 1,650 Japanese sailors going down with her. The underlying CG model used on Taiho was created by Forkasiewicz’s colleague Waldemar Góralski, whose work is stunning in its complexity and hyperreality. Taiho by Piotr Forkasiewicz