THE GHOSTS OF SOUTHERN ALBERTA

I'm am Eastern boy. Of that there's no doubt. Liberal, urban, soft—a bit of a pussy by Alberta standards. But when I sweep down out of Calgary on Highway 2, the farther south I get, the more I feel I belong there. Perhaps it's the blue dome of the sky and the startling vistas, the heartless winter winds, the direct, no-nonsense men, the uber-competent women or maybe it's the fading ghosts that surround me from a time long past when men from the east and west came together here to prepare for war.

I've driven out of Nanton a number of times with pilot Todd Lemieux, headed east of Highway 533 towards Vulcan, Alberta to go flying or exploring. About 20 kilometers along 533, the highway takes a hard left north and becomes Alberta Highway 804. Right after that turn, you come to Regional Road 163 which runs due east again and arrow straight for another 12 Kilometers over a flat skillet landscape. After five minutes, the land to the south of the road begins to rise imperceptibly. One moment there is nothing but a rise in the floor of the west and the next there is a glimpse of history. Out on the horizon line that separates the vastness of the Alberta sky from the vastness of the Alberta prairie something appears out of nowhere in the heat shimmer—a series of long, low structures, silhouetted darkly against the morning sun in the east—like the long and short dashes of a morse code calling out from time, calling men together, calling men to sacrifice.

These are the six remaining hangars of No. 19 Service Flying Training School at Vulcan, Alberta, a Second World War training airfield of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. It's difficult to grasp their scale as you roll toward them, but if you turn south onto Range Road 253, their presence grows and spreads and you get the sense that something important happened here long ago. If you pull your car to the shoulder of 253 and get out, you can cock your ear towards the closest hangar a hundred yards away. The sounds of the prairie—the shrill chatter of a merlin on the hangar's parapet, the rustle of grass and the ting of the fence wire, the distant, low-gear protest of a farm truck—are all carried on the wind. And far beneath that—down 75 years deep where only a believer can hear it, the aural memory of a time long past. It's the faintest remnant of the clamour of falling wrenches, hammers and compressed air, the cough of radials, the chirp of tyres on tarmac, a distant gramophone scratching, the shouts of young men, the notes of a long-vanished station band—the Ghosts of Southern Alberta.

The long and short dashes of history—the hangar line at Vulcan aerodrome today as seen from Vulcan County Regional Road 163. Photo: Google Maps Streetview

Background

The Second World War was a time of powerful stresses on nations, on ethnicities, on families, and on economies around the globe. Hundreds of thousands of families, in every corner of the world, would offer up, with grim reluctance, their sons and even daughters and lay them down on the altar of liberty. The best of this young generation was to be given the task and the training to push back a darkness that was devouring freedom, territory and lives. They were about to save the world.

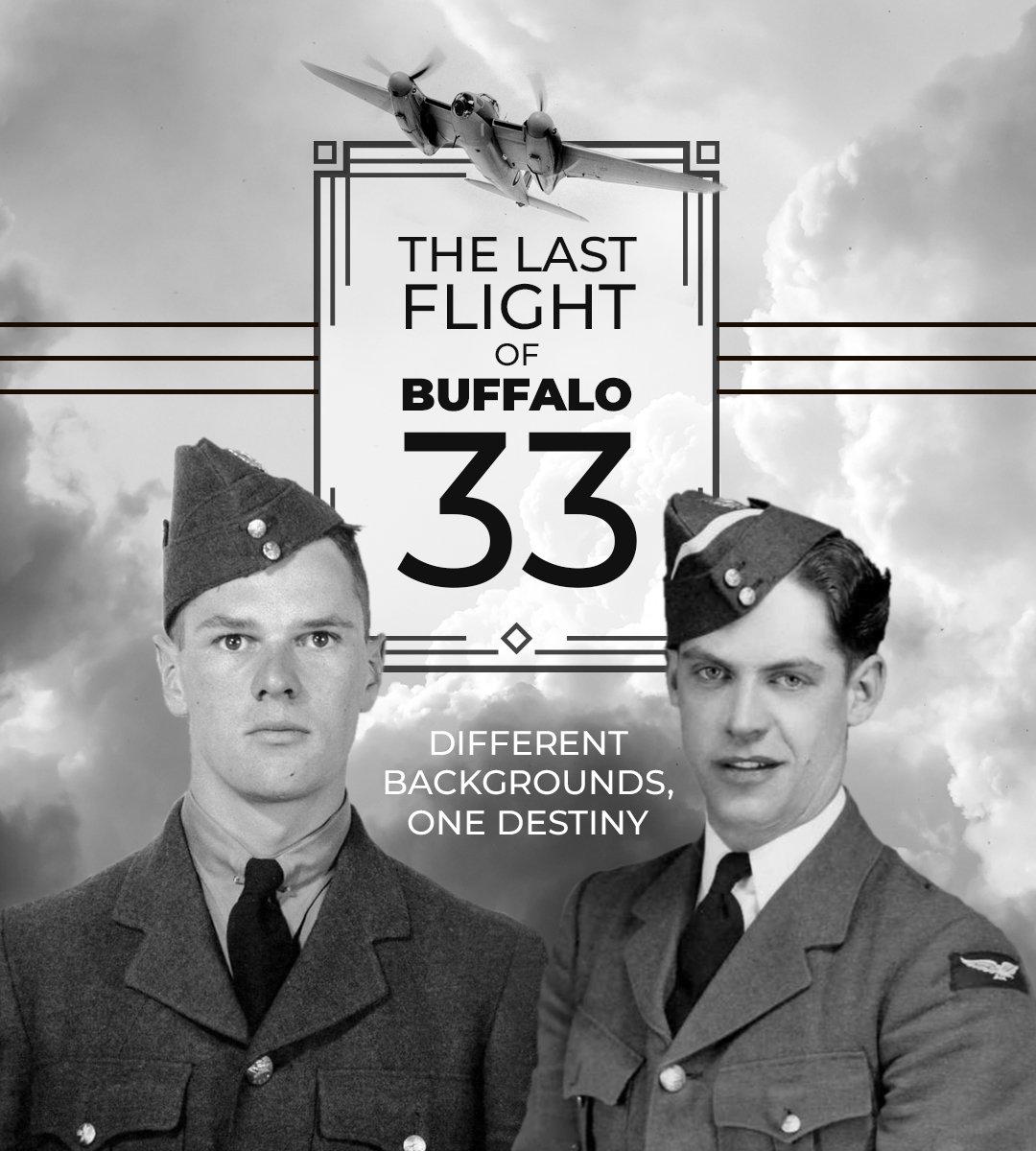

From 1939 to 1944, as part of this global sacrifice, there was a great gathering that brought together young men from around the world. It was a coming together of avenging angels—men who would take the fight against this darkness to the air in proportions not even dreamed of just a few years before, in machines of great power and lethality. Though the souls for the task at hand were drawn from disparate places like New Zealand, Jamaica, Scotland, Norway, and Australia, the trysting place would be the small towns and rural hamlets of Canada, as well as larger urban centres such as Moncton, Toronto, Fort William, Winnipeg, Calgary, and Vancouver, to name just a few..

Men boarded great grey ships at Sydney's Circular Quay or perhaps the docks of Great Britain, rode trains from Toronto's Union Station, or walked across the border from the United States and resolutely made their way through initial training schools to the vast, sky-dominated and peaceful prairie landscape. As part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), Canada would put into motion a logistical and engineering project of such monumental proportions for the country of only 11 million citizens, that it dwarfed the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway, the ribbon of steel that united our country before confederation—something Canadians consider the gold standard in federal infrastructure projects. Inside of two years, Canadians scouted, surveyed, and built more than 150 airfields, established almost 100 training schools for pilots and aircrew, built the syllabi and training equipment and the thousands of aircraft needed. The cost exceeded 2.25 billion in 1939 dollars (approximately 36 billion dollars today), and Canada paid for 75% of it.

During this build-up time, recruitment began in earnest and in all corners of the country and the Commonwealth—a cattle farmer's son from Victoria, Australia, a bookkeeper from Oshawa, Ontario, a missionary's son from Philadelphia, a gas jockey from Sherbrooke, Québec, an apprentice butcher from Aberdeen, Scotland, a law student from Montréal, Québec. The system sorted them out by skills or needs, assigned them to schools across the country, and fed them into the maw of the BCATP.

Canadian BCATP bases were spread from coast to coast, but primarily they took place in the Canadian provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario. To make room for flying operations, and to keep the skies relatively uncrowded, these airfields and schools were dispersed far and wide, with most of them located within five to 20 kilometres from a small rural town. This was done to maintain proximity to a source of support workers, materiel, and food, as well as give marooned students some sort of night life. For many of these bases, one, two, or even three relief landing fields were created to relieve congestion at the main field as scores of aircraft shot touch-and-goes and did circuits. In themselves, these were often complete airports with buildings and paved runways and staff.

If you grew up in a small town like Claresholm, Alberta, in the 1930s, life was nothing short of predictable. Work was never-ending, winters were hard, oh so hard, church was obligatory, marital prospects were limited, and one's view of the world at large was what you could glean from newspapers. The great tectonic shifts in world politics, militarism and technology were things that happened over the horizon—far, far over the horizon. But in 1940, the world at large, with its fears, stresses, strange accents and brave young men, came marching over that horizon and encamped just outside of the town limits of many a small town in Canada.

The men who would populate the schools across the country were brought there by the trains of the CNR and CPR. Overnight, the great railway system of Canada was primarily in the employ of the war effort. Here, a recently graduated class of observers/navigators from No. 31 Air Navigation School pose with the train that will take them from the small town of Goderich, Ontario, to their uncertain futures at the war front. Photo via Phil Wilson

Related Stories

Click on image

Suddenly there were year-round jobs for men and women. There was local business growth where there had been nothing for decades, save a shrinking economy shattered by the Great Depression. Everyone was benefiting from these new aviation schools—from bakers and builders to teamsters and casket makers. Every room in town that could be rented was filled with military and civilian instructors. Overnight, there were hundreds of virile, exuberant, polite, and lonely young men walking around town. Local society was transformed in a prairie heartbeat. There were dances, socials, fundraisers, love affairs, and barroom fights. The impacts on these small towns were huge and, for some like Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, they would be permanent. In some towns, the BCATP blew through town like a summer prairie storm, straining the fabric of the community for just a couple of years and then it was gone, or at least the flow of young men who brought it to life had dried up overnight and the bases were closed. Some large bases, populated by more than a thousand students and staff, were opened and shut down in just two years. The local economy went from zero to a hundred miles an hour and back down to zero just as quickly.

The network of BCATP schools was established in breathtaking speed; some airfields were operational within a year. The last came online in 1942. Despite the stupendous cost and effort to create these schools and despite the success of the project and massive output of qualified and motivated young aviators, war planners could read the writing on the wall. The darkness was receding, the fascists were weakening and reeling backwards. Soon, the bloodletting would stop. It was time to cut the flow of blood off at the source—the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. By late 1944 and early 1945, a few of these brand-new schools were shut down and the bases closed.

Some, like Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, Portage La Prairie, Manitoba, and Bagotville, Quebec, remain as RCAF bases to this day. Others, like Claresholm and Penhold, Alberta, would be reactivated for military training service after a short closure and then fade away once again. Some saw a short-term second life as storage, maintenance, and disposal facilities for the thousands of training and combat aircraft that had been needed for the war effort, but were now surplus to requirements. The lucky ones, located near larger communities such as Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, or Arnprior, Ontario, were, in time, handed over to the communities that birthed them, to become the local airport and the seed for industrial development. Many still function today.

Almost all the relief landing fields and many of the more remote bases have declined, deteriorated, or simply vanished, consumed by the landscape that once fostered them. All that remains of many are crumbled runways, hangar floor slabs, abandoned gunnery backstops (gun butts) and, in some cases, just a faint wisp of memory, a discolouration upon the land. Only one base, No. 31 Bombing and Gunnery School (B&GS), at Picton, Ontario, exists intact to this day—a time capsule from a period most Canadians have forgotten.

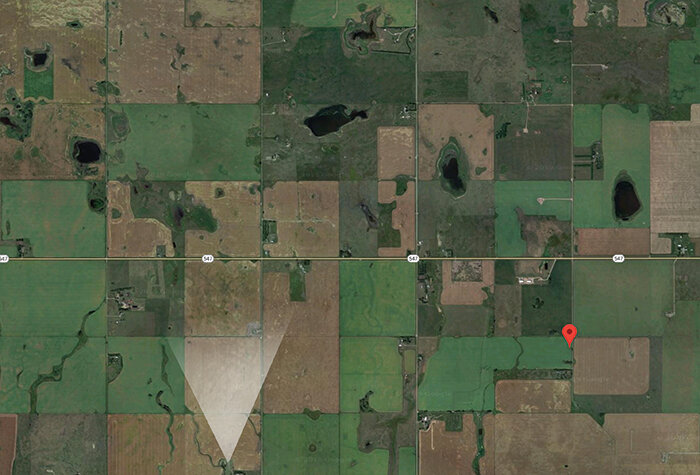

Years ago, while flying across the Prairies with the late Bruce Evans in his T-28 Trojan, we spotted one single BCATP base off to the south of our track, its broken runways catching the light enough to distinguish it from the surrounding farmland. There was but one structure where once there had been a small town. It was a ghost, caught in the open sunlight, a single footprint from a massive military beast, left upon the prairie. It got me to thinking: “What is still visible of this enterprise today?”

Using Google Maps-Satellite as a camera, I searched the Prairies for the remains of the greatest engineering accomplishment in Canadian history. Scrolling across the countryside in “my satellite,” many of the familiar triangular airfields, invisible from a passing car, were clearly visible. Others had left only the faintest of spoor, while others had vanished into the prairie grass. Using the Canadian province of Alberta as my boundary, I tracked down via satellite all that is still visible from above today. Then, two Alberta pilots—Todd Lemieux and Lori Fitzgerald—surveyed the sites of many of the old airfields in Todd's Citabria to give me the most up-to-date images of these old aviation fossils. Seventy years from now, much of what you will see in the following images will cease to exist. Here now, compiled for your edification, are all the bases of the BCATP that were located in Alberta—what they look like today, a few thoughts about their past, a few images from the war or their later life, a wave goodbye.

Todd Lemieux on the stick and Lori Fitzgerald on the camera in search of the old ghosts of Alberta. In April of 2019, the two veteran pilots made a flight plan that would take them over many of the Southern Alberta airfields to capture what could still be seen. Photo: Todd Lemieux

A wonderful hand-notated flight map of part of Southern Alberta, likely used by a student or perhaps an instructor. I believe that the ovals surrounding the aerodromes were added later to highlight them on the web. However, there are handwritten notations pinpointing the instructional flying areas for High River—dual (instructor-student) flying to the east, low-flying close to the aerodrome, and a solo aerobatic practice area to the west. On this map, Calgary is about 10% the size it is today. Map via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

No. 15 Service Flying Training School, No. 3 Flying Training School

Claresholm, Alberta

No. 15 SFTS at Claresholm was opened on June 9, 1941 with much fanfare and local dignitaries in attendance. The school was a multi-engine service flying training school, training pilots who largely populated the squadrons of Bomber, Transport and Coastal Command. A story in the Lethbridge Herald newspaper of the day tells the story of its beginnings:

UNIFORMED MEMBERS OF AIR FORCE MINGLE WITH EARLY PIONEERS

CLARESHOLM, Aug. 14—The thriving little community of Claresholm in the centre of one of the finest wheat producing areas in Canada, has come a long way since the first citizen to settle in the district, the late Col. W. A. Lynden drove overland from Utah in 1881, and the first of the steel [railway – Ed] reached here in 1896. Today when you walk down her streets, you will see the big cattle rancher, the world-famous cowboys, the many fine wheat farmers; and mingling with these will be the blue grey of the Royal Canadian Air Force. For situated two and a half miles west of town is No. 15 Service Flying Training School where over 600 men are stationed.

The facilities at Claresholm included two relief landing fields—one at Woodhouse to the south and one at Pulteney, Alberta, to the north—both situated along Alberta Highway 2, the main north-south route in Southern Alberta. Both communities were no more than a couple of houses on the main road, yet they gave their names to history. Not much of these two fields remains today, but Claresholm has six of the original seven hangars still in use as well as several ancillary buildings.

No. 15 SFTS was a service flying training school, providing advanced flying instruction on the Avro Anson and Cessna Crane for pilots selected for multi-engine flying. The bulk of these young men went on to pilot Vickers Wellingtons, Handley Page Halifaxes, Avro Lancasters, Douglas Dakotas and the like, but some went to de Havilland Mosquitos, Bristol Beaufighters, and even Short Sunderlands. The first course at No. 15 included 40 Canadian members of the RCAF, but as training developed, the make-up of these courses would change to include Australians, New Zealanders, Britons, and Americans (the flow of American trainees dried up when the USA finally entered the war at the end of 1941).

From April to September of 1942, Claresholm was home to No. 2 Flight Instructor School, but this unit soon moved to the brand-new base at Vulcan, Alberta, some 50 kilometres to the northeast. No. 15 stayed in steady operation until the end of the war in Europe, closing on May 30, 1945. Some 1,800 pilots had their wings pinned on them on the ramp at Claresholm during that time.

Throughout the rest of the 1940s and into the 50s, the base remained commissioned but dormant with only a skeleton staff. Though Claresholm would soon become an active base, the relief fields at Woodhouse and Pulteney were abandoned. Little remains of them today. In 1951, the base was reopened to provide training for pilots as part of the NATO Aircrew Training Plan. The unit based at Claresholm for this purpose was No. 3 Flying Training School and its students came from all over the NATO alliance. The base expanded to accommodate the new peacetime program, including Private Married Quarters (PMQs) for staff families—140 housing units in all—a grocery store, an eight-classroom school, and two chapels. Claresholm was now a large and busy place with a permanent staff of 1,100 military and civilian employees.

The base at Claresholm closed down in the summer of 1958 and No. 3 FTS left for Gimli, Manitoba, to continue operations. Not much happened at Claresholm for the next few decades, except for some auto racing on the runways, something that many abandoned bases were used for across Canada in the 1960s and 70s. Today, Claresholm airfield is one of the lucky ones—now a municipal industrial park and airport, with six of the seven hangars still standing.

Number 15 Service Flying Training School at Claresholm, Alberta. No other photo demonstrates the extraordinary flight training environment of the western Canadian provinces than this old black-and-white photo of RCAF Station Claresholm in the war years. Flat and obstruction-free, the wheat fields of Southern Alberta offered plenty of opportunity for young pilots to screw up and still have a chance at survival with a forced landing. The town of Claresholm can be seen a couple of miles to the north and east in this photo and appears to be about the same size as its airfield. Photo: RCAF

A view of No. 15 SFTS shot in the spring of 2019 from a similar angle, with the town of Claresholm off in the distance and the broad prairie sailing to the horizon. Photo: Lori Fitzgerald

A satellite photo of Claresholm today. The airfield serves double duty as the local airport (Runway 03-21 remains in operation) and as a sort of industrial park with six of the original flightline hangars still in existence. Several of these hangars are in terrible disrepair and most of the base ancillary buildings have been taken down. Still, if you drive the old streets of the base today, it feels somehow alive—a pale shade of its former vibrancy, but with an undeniable pulse. Photo via Google Maps

Fading into history. When I first began this story more than three years ago, one could clearly see the remains of the No. 15 SFTS relief field at Woodhouse, Alberta, on the satellite view of Google Maps—top image, right hand side. The remains of its three distinctive runways were still visible. But just three years later, I checked it again and there exists only the faintest discolouration to mark the spot where so many trained. Images via Google Maps

Todd Lemieux and Lori Fitzgerald set out this spring to find remnants of many of the southern Alberta airfields. In this shot of Claresholm's relief field at Woodhouse, looking north, we can still just see the faint fossil of the old runways. Photo: Lori Fitzgerald

A few of the relief fields had grass runways and of those, like Pulteney, Alberta, Claresholm's other field, not even the faintest trace exists. Transports and tourists roll down Alberta Highway 2 (left is north), past the old site and there is no sign that, 75 years ago, young men trained here for war, many of whom did not come home. Photo: Lori Fitzgerald

Like all of the BCATP training schools, Claresholm had its share of accidents and tragedies. In the war years, there was a higher tolerance for loss of life and equipment than what would be acceptable today. One striking accident captured in this image had a happier outcome that the photo would indicate. The website of the Bomber Command Museum in nearby Nanton explains: “The school was the site of a rather spectacular accident. A Cessna Crane aircraft with two students aboard had an engine failure over the aerodrome and while trying to go around again after a single engine approach, lost altitude and dived right into barracks block 11, occupied by the Service Police. Crashing through the roof and landing on top of the bunks, it pinned down one man sleeping in the lower bunk so that he could not move. It was rather fortunate that the man in the top bunk, a few minutes before, had retired to the washroom. Needless to say, the remainder of the men were rather startled to find a Jacobs engine in bed with them, or in the close vicinity. Injuries were sustained by some seven servicemen in and by the two airmen. The remarkable thing about the accident was that there was no loss of life, and when the crash crew arrived on scene, two very scared looking pilots were extracted from the jumble of aircraft, beds, and building with hardly a scratch on them.” Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada

Many former training airfields of the BCATP have memorials to the field and to the young men who were killed in training. Claresholm had more than its share as this plaque attests—21 in all. Three of the Australians from the base—McKittrick, Bennet, and Baker—were killed in the same accident on July 20, 1944, when the Anson they were in crashed near the small town of Arrowood, Alberta, some 100 kilometres north of the Claresholm field. In those days, foreign airmen were buried near their bases, while the bodies of most Canadian and American airmen were transported home by train. The plaque and memorial were raised in 1997, more than 40 years after the war.

Scenes from the military funeral of McKittrick, Bennet, and Baker. They were laid to rest in the Claresholm town cemetery with local ministers and chaplains in attendance. Across Canada there are as many graveyards like this as there are training bases. In them are buried the remains of hundreds of Commonwealth and Allied airmen who never got to fight in the war. In many cases, their families would never be able to journey from Australia, New Zealand, and other places to visit their son's final resting place. Many would never really learn the circumstances of their deaths. But one thing is certain, these graves were and still are well tended by local volunteers. I have visited many of these graveyards and have never seen a headstone or plot in disrepair. Photos via Bomber Command Museum of Canada

A photo of a wartime graduating course of pilots at Claresholm's No. 15 SFTS posing in front of hangar doors. The pilots are all wearing their brand-new wings and sergeant stripes. We know this is right after their wings parade because they all still have their white aircrew training cap flashes.

Flying Officer Pat Donaghy, reader and contributor to Vintage News, sent me a series of photographs from his post-war time training on Harvards at Claresholm. This formal group photo is of his flying training cadre—Course No. 44 NATO Air Training Plan which assembled at No. 3 FTS, Claresholm, Alberta early August 1952. This photo was taken August 6, 1952 at the very start of the course. Trainee pilots were from the RCAF, RAF, Netherlands Air Force and L'Armée de l'Air (French Air Force). The French pilots were there only for a few weeks and then sent to a School of English. Back Row: Peter Aarts, Jackie Vegtel (Netherlands Air Force (NAF)); Al Hesjedahl of Bengough, Saskatchewan, Gord Vincent from Nova Scotia, Malcolm Bayne of Ottawa,(RCAF); Theo de Jager (NAF); Harry Jordan, Johnny Lidiard, Tony Loftus, Tim Carter, Lawrie, (RAF); Centre Row: Pat Donaghy of Flin Flon, Manitoba, (RCAF); Noel Van der Haar (NAF); LaBarthe, (FAF); Jacques Desmarais, (RCAF); Shim Folkers (NAF); Larry Forbes of Montreal, (RCAF); Pearce,(RAF); Gerry Thorneycroft from Swift Current, Sask. (RCAF); "Tinker" Bell (RAF); Front Row: Simmonet, DeNeve (FAF); Eric Das (NAF); Gerry Coles, Taff James, Bert Conchie, Ron Evans, "Tank" Martin, (RAF); Johnny Glover of Guelph, Ont., Keith Armstrong of Richards Landing, Ont.Photo: Pat Donaghy

Pat Donaghy (Left, Middle row) and his fellow Canadians on Course No. 44 at Claresholm pose in their best uniforms and white aircrew trainee cap flashes in front of an H-hut entrance. Top Row (L-R): Malcolm Bayne, Gordon Vincent, Gerry Thorneycroft; Middle Row: Pat Donaghy, Al Hesjedahl, Keith Armstrong, Bottom Row: Larry Forbes, Jacques Desmarais, Johnny Glover. There have been a number of Thorneycrofts in the RCAF since the war. Jacques Desmarais is better known in the RCAF and Canadian flying circles by his nom-de-plume—Ace McCool. Ace McCool was a much-loved humour column written in Canadian Aviation magazine and accompanied by cartoon illustrations. E.E. “Al” Hesjedahl went on to fly CF-100s as an air show performer just four years later. Photo: Pat Donaghy

Flying student Leading Aircraftman Patrick Donaghy is “rarin' to go” as he gets set to climb into a North American Harvard II, one of hundreds built in Canada by Canadian Car and Foundry at Port Arthur, Ontario. Donaghy flew both Mk II and Mk IV Harvards at Claresholm. He was part of a test group that began primary/elementary flying training on Harvards right out of the gate. During the Second World War, pilots started out on much less complex aircraft such as the Fleet Finch, de Havilland Tiger Moth or Fairchild Cornell and then went on the earn their wings on Harvards at a Service Flying Training School. Donaghy and his cadre started on Harvards but when they had mastered this demanding aircraft, they did not get their pilot's wings. Instead they went on to a T-33 jet course from which they would graduate with their brevets. Photo: Pat Donaghy

In contrast to the glamour shot in the previous photo is this image that it wasd not all fun at Claresholm. Here Larry Forbes (left), Malcom Bayne and Donaghy (right) take out the trash from the classroom at Claresholm. Photo: Pat Donaghy

During his training on Harvards, student pilot Donaghy executed a textbook dead-stick, wheels-up landing in a wheat stubblefield west of the airfield in October of 1952. Dongahy explains: “ SOP [Standard Operating Procedure-Ed.] was on the first start of the day we were to give the engine 30 seconds of oil dilution. The theory being it provided better scavenging and cleaner running engines. So on this particular day I flipped the spring loaded switch UP for 30 seconds, released it and it snapped down and OFF. The circuit was very busy and I spent 10 or 12 minutes in the line-up before getting clearance for T/O. I was climbing out and about 400 feet oil and smoke came pouring out under the engine cowling and some flames could be seen. The windshield became partially obscured. I immediately shut down the power and the oil and smoke decreased. There were no end of level stubble-covered fields and I concentrated on maintaining the proper glide speed. I called, "Claresholm Tower, 346, I have an fire in the air off the end of 20!" Just before I shut OFF the battery master switch a casual reply, "346, understand you have a fire in the air?" There was one lone cow or steer in the field I had selected and my thoughts were, "Move, damn you animal, cause I'm not making any turns at this altitude!" It sensed or heard me and headed yonder. The touchdown was relatively smooth and before I knew it I was about 50 feet away fumbling at the 'chute Quick Release. I went back and checked in the cockpit to make sure ALL the switches were in their correct position. Within minutes there were a couple a/c orbiting overhead. What I hadn't noticed on the approach was a farmer riding a tractor along the fence-line bordering my landing field. He stopped and climbed over the fence and strolled up to the Harvard and said to me, "Well you sure scared the shit outta my cow!" An investigation discovered that while the dilution switch did go OFF, the solenoid controlling the dilution pump failed and continued to RUN pumping gasoline into the oil tank all the while I was waiting for T/O clearance. When T/O power was applied the now excessively diluted oil forced its way under the rocker box gaskets and onto the hot exhaust pipes. A repair was made and a new prop installed and a few months later I again flew 20346.” Photo: Pat Donaghy

Wings level and little damage—about the best outcome possible for a dead-stick and wheels-up landing. They trained them well in those days! Photo: Pat Donaghy

The gasoline-diluted oil was forced out and caught fire on the hot exhaust pipe. Thanks to Donaghy's training and quick action, the damage was minimal. Photo: Pat Donaghy

Harvard 20346 was recovered and fixed in time for Donaghy to fly it again during his training course. Photo: Pat Donaghy

Donaghy's Course No. 44 graduation picture. Instuctors are in the front row (Left to right): Flying Officers Bullis, Webster, Ledgerwood, Gray, Flight Lieutenant Josh Linford (RAF exchange officer & Flight Commander Course 44.) Flying Officers Mitchell, Stevenson, Molyneaux, Campbell, Grant, and Abell. On the Wing: Conchie, Vander Haar, Heffernan, Martin, Steer, Lidiard, Aarts, Armstrong, Forbes, McDonald, Bell. Standing: Coles, Thorneycroft, Glover, Donaghy, Hesjedahl, Carter, Garland, DeJager, Jordan, Folkers, Vincent, Das, Vegtal, Desmarais, Evans, James. Photo: Pat Donaghy

Flight students at Claresholm: Back row: Tim Carter, "Tinker" Bell (with his distinctive RAF mustache), Larry Forbes, John Glover, Al Hesjedahl. Front Row: Pat Donaghy, Gerry Thorneycroft, Ron Evans, "Tank" Martin, Keith Armstrong. Photo: Pat Donaghy

A good photo of Claresholm after the war with runways well marked for NATO pilot training.

For a while after NATO training left for Gimli, Manitoba, and the base was abandoned by the RCAF, Claresholm became known for having, of all things, the finest restaurant in all of Alberta—The Flying “N” Inn Restaurant, run by chef Jean Hoare from one of the old BCATP structures. People made the 1.25-hour drive from Calgary for their legendary steaks and smorgasbord. Even Bing Crosby found himself at one of Hoare's tables, ordering her signature “Chicken In The Gold” dish. Here we see some locals (top) leaving on January 1, 1981, after a big New Year's bash (bottom photo) following a year-long celebration in Alberta for its 75th birthday. Politicians, dignitaries and business people were in abundance and Jean Hoare's fame was at its peak.

Jean Hoare's cookbook of recipes from the Flying “N” and a matchbook that touts her Famous Smorgasbord and her specialty in Alberta beef steaks

The high cost of maintaining these old wooden structures means that they have little value for most modern businesses. Claresholm is a rather fortunate old base. Six of the original seven hangars on the line are still being used—although mostly for businesses other than aviation. One has been taken down to the slab and this one is close to death. Photo: Dave O'Malley

Another sad view of one of the large flightline hangars shows a deplorable state of deterioration. Though this one is up for sale, it is really the land that it's on that retains any value. Photo: Dave O'Malley

The street names on the old Claresholm station have aviation-based names—Harvard Drive and Tiger Moth Way being two of them. Photo: Dave O'Malley

The impact of RCAF Station Claresholm on the town was enormous. Six years after the BCATP base closed in 1945, the school was reopened as No. 3 Flying Training School for the purpose of training NATO pilots using the single-engine Harvard IV. During the 1950s there were more than a thousand RCAF personnel stationed in Claresholm, including Canadian and international pilot trainees who learned to fly there. The base was officially closed again in 1958. A Harvard aircraft, much like the ones used during the training, can be found on display at Centennial Park along Starline Road—the road that leads out of town to the airport.

Although the closing of the flying school was a major loss to Claresholm, the air force hangars were subsequently converted to industrial uses and have, over the years, provided diversified job opportunities for the industrious workers from Claresholm and area.

No. 36 Elementary Flying Training School, No. 3 Air Observer School

No. 2 Flight Instructors School

Pearce, Alberta

One of the more isolated aerodromes in Southern Alberta was built just north of the tiny and now non-existent hamlet of Pearce in a mile-wide bend in the Oldman River. If you put a boat in the river here in 1942, you could follow it to where it joins the Bow River and then the South Saskatchewan River, taking it all the way to Hudson Bay. The BCATP surveyed the flat plateau in the crook of the bend and began construction of a flying training base in 1941, which was to be operated by the Royal Air Force and which was populated with flying students from Great Britain.

The base was opened by the RAF on 30 March 1942 as No. 36 Elementary Flying Training School with initial instruction on the Tiger Moth followed briefly the highly capable but totally unsuitable Stearman Kadet Mk.I. The stout (compared to the Finch and Tiger Moth) initial trainer arrived at RAF-run air bases in the summer of 1942 and stayed in service with 36 EFTS until the school was closed mid-August of the same year—just four and a half months after it opened. The Stearman Kadet was considered an outstanding trainer... until the temperatures dropped with the approach of winter. It was not equipped with a coupe-top canopy or any form of cockpit heat and, as a result, was brutally cold in late fall and winter operations—so much so that pilots were issued leather face masks to prevent frostbite. Luckily, the students at Pearce were gone before they had to face the Stearman Kadet's fatal flaw. By early 1943, all 300 Stearman Kadet trainers had been returned to the USA.

No. 3 Air Observer School (AOS), based at Regina, Saskatchewan, opened a detachment at the aerodrome on 12 September 1942. The AOS operated Avro Anson twin-engine navigation trainers and an eight-week course at the Pearce aerodrome until 6 June 1943, when both the Pearce and Regina detachments of No. 3 closed for good.

No. 2 Flying Instructors School, which had previously been housed at Vulcan, Alberta, relocated to Pearce on 3 May 1943. The school took newly winged pilots from other Service Flying Training Schools across the land and taught them to be flight instructors. Needless to say, most of these men, who were keen to join the fight in Europe and North Africa, were disappointed in their selection for instructor training. Pearce's longest-running resident training school provided instruction on the wide variety of aircraft then operated by flying schools across the BCATP—Fleet Finches, Fleet Fawns, de Havilland Tiger Moths, Fairchild Cornells, and Harvards for single engine courses and Cessna Cranes, Avro Ansons and Airspeed Oxfords for multi-engine courses. The school closed on 20 January 1945.

Although the airfield was abandoned operationally, the facility continued to be used as a storage depot and scrap yard. On 8 September 1945, 83 four-engined Lancasters, originally intended for use against the Japanese landed at Pearce (now called Pearce depot). Here they would be put in storage, pending a decision about their fate, along with other aircraft of the BCATP. All of the Lancasters were kept flyable by a skeleton maintenance crew. Some were returned to service as maritime patrol aircraft, some were scavenged for parts, but most were sold for scrap.

The depot closed down for good in 1960. Today, the site is home to a large dairy farm.

The impact of RCAF Station Claresholm on the town was enormous. Six years after the BCATP base closed in 1945, the school was reopened as No. 3 Flying Training School for the purpose of training NATO pilots using the single-engine Harvard IV. During the 1950s there were more than a thousand RCAF personnel stationed in Claresholm, including Canadian and international pilot trainees who learned to fly there. The base was officially closed again in 1958. A Harvard aircraft, much like the ones used during the training, can be found on display at Centennial Park along Starline Road—the road that leads out of town to the airport.

The muddy Old Man River curves around the site of the former No. 36 Elementary Flying Training School at Pearce. One gets a good sense of how large the centre-pivot irrigation circles are—with diameters as long as a runway. Photo via Google Maps

Pearce, Alberta, was a very small place as was witnessed by the size of its train station. Here a group of young Royal Air Force Leading Aircraftmen, with their white aircrew training cap flashes, pose as they wait for a train—perhaps to take them to a bigger centre like Lethbridge or Calgary where they might find some fun. In the distance on the left we can see the grain elevators that once marked every community on the prairies. The men, station, the track, the elevators, and even the town have all since vanished. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

As an Elementary Flying Training School run by the Royal Air Force in the early part of the Second World War, Pearce was home to the magnificent but entirely unsuitable Stearman Kadet. The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan acquired 300 of the sturdy and powerful trainers, but they arrived without the required winter-weather equipment, primarily a coupe-top canopy for winter flying. Within only a few months, they were deemed inadequate for Canadian winters and were returned to the United States in groups over the next few months. The Stearman Kadets were used only in Alberta, and only to train Royal Air Force flight students. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Flying instructors, staff officers, and other staff at Pearce posing in front of a Cessna Crane. Front row (centre) Wing Commander Sharpe (Chief Flying Instructor); on his right S/L D. L. G. Jones; on his left S/L E. L. Gosling. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Winters in Southern Alberta are tough enough, but when one is isolated on a remote air training base with nothing to do, sport takes on a life all its own. The bases in the south formed an extremely competitive ice hockey federation known as the Southern Alberta Air Force Hockey League (SAAFHL), with teams such as the Pearce Professors, Fort Macleod Playboys, Vulcan Hawks, Claresholm Falcons, Lethbridge Gunners, and the Lethbridge Bombers (No. 8 B&GS). The league actually started in January 1942 as the Southern Alberta Service Hockey League and included an Army team from Lethbridge. The Pearce Professors were one of the more accomplished teams. The caption with this photo in the Lethbridge Herald explains: Yes, you're right! There was plenty of room for more fans to watch this power play of Claresholm Falcons against Pearce Professors the other evening at the local arena. Profs won the game 9-7, but it took a sustained battle to do the trick. Dishing up fast and bruising hockey at every stand, the five teams in the Southern Alberta Air Force Hockey League merit much better attendance than they have been playing before in most games. (Note to the reader: these seats will be waiting for you tomorrow night, when Professors entertain Lethbridge Bombers in the local ice palace.) Photo via Lethbridge Herald

You win some, you lose some. From digital records of the Lethbridge Herald, it was obvious that the Pearce Professors were a dominant team, but the league was highly competitive. Back in the day, the name Professors had perhaps a tougher cachet than it would today. These teams were mostly made up of base personal and staff pilots rather than students, who were transient and extremely busy with course work and flying. Image: Lethbridge Herald clippings

Scores of Avro Anson trainers await their fate at Pearce in October of 1945 after an early winter snow. Within a couple of years, they would all be gone to the scrapyard or to the odd civilian buyer. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

The only known photograph of a Lancaster arriving at Pearce in 1945. Pearce was closed down and vacant by January of 1945, and then officially reopened on 7 September 1945 to accept incoming Tiger Force Lancasters. The very next afternoon, 83 Lancaster Mk 10 bombers arrived and landed at the old base. This shot was taken by Ray Wise, an RCAF mechanic who was tasked, along with a Corporal Edge, LAC Cook, and LAC Wyers, to take care of a large number of Lancaster aircraft that were soon to land... and land they did. Ray Wise was 92 years of age when he was interviewed by Clarence Simonsen, Canada’s leading authority on nose art, and Jim Blondeau, a documentary filmmaker with Dunrobin Castle Productions. Blondeau remembers, “... he still spoke with excitement about the spectacular arrival and low flying air show they witnessed at Pearce on that one single fall afternoon. Out in the middle of nowhere the ferry crew pilots showed their low-level flying skills, terrifying nearby farm animals and the local Alberta farmers. Ray Wise also helped to record and save Canadian history when he took along his camera. His collection shows Anson ferry pilot aircraft, the rows of Lancaster bombers, and most of all, the Canadian Nose Art, painted on our most famous Lancaster aircraft. Just 18 months after the photos were taken, some of these aircraft were unceremoniously scrapped without any due thought by Canadian authorities. Once the Lancaster bombers had arrived they were parked in long rows and each morning the four mechanics were ordered to start each of the four Merlin engines on all the 83 aircraft. Over the next six months ferry crews arrived at Pearce and the Lancaster aircraft were flown to various long-term storage areas in southern Alberta. The mechanics were also ordered to prepare as many bombers as the Pearce hangars could hold for long-term storage.” Photo by Ray Wise via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Some of the Pearce ground crew, tasked with the daily upkeep of the grounded Lancasters after the war, stand on a scaffold next to a combat veteran Canadian Lancaster with 51 sorties—clearly on a warm day in the fall of 1945. Photo by Ray Wise via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A few Lancs and an Anson stored at Pearce after the war. It is interesting to note that the bomb doors seem to be open in most of these photographs from the storage operation. One would think that they would have been closed to keep birds from nesting in the bays, but the stress on the hydraulic system was reduced by dropping them open. As well, John Coleman says, “Since the engines were started daily, that they were left open on purpose. When we start our Lanc the bomb doors ALWAYS must be open. Early in the Lanc’s career they lost a few to massive explosions. It turns out that fuel vapours tend to collect in the bomb bay.” Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Lancasters at Pearce in the final days, with collectors and mechanics picking over the bones. The 70 or more, which were selected for Cold War patrol, were the lucky ones—but just for a few years more. This is the sad end of many of the Canadian Lancasters: rotting and crumbling, being picked over, shat on by pigeons, fading under the prairie sun. Canada’s leading aviation historian and publisher summed it up perfectly: “Barnyard bombers were well worth the fifty dollars asking price. To begin with, a farmer could count on recouping his investment by simply draining gas and antifreeze from his plane. Tires were just fine for a farm wagon. A tailwheel fit the wheelbarrow. For years to come the carcass would be a veritable hardware store of nuts and bolts, piping and wiring. In the meantime, it made a suitable chicken coop or storage shed. One farmer converted the nose of his Anson into a snowmobile.” Photo via Larry Milberry, Aviation in Canada, Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Ltd., 1979

Looking at this photo of the last Lancs at Pearce, there is nothing more to say. Photo via Palsky Family

Todd Lemieux circles the ghost of Pearce, Alberta in 2018. The cows and milking machines of the Airport Dairy Farm now occupy the land that once housed men and flying machines. The sun and winter snows have broken the pavement and the runways are well on their way to be absorbed back into the land Photo: Todd Lemieux

The runways of Pearce in the spring of 2019. more than 70 years ago, these ramps and grass aprons were crowded with hundreds of aircraft: Ansons bound for the scrapper, Lancasters home from the war and awaiting a second life as maritime patrol aircraft. Her long-gone barracks were once occupied by maintenance crews to look after the aircraft and ferry pilots overnighting before moving on. Photo: Lori Fitzgerald

The front gate of Pearce in 2004. The website for Alberta Milk, an association representing Alberta's dairy farmers, says this about Airport Dairy: “Honoring the Past. Harvey Van Hierden grew up on the family dairy farm just east of Fort Macleod. After marrying Bernita (who grew up on a dairy farm in Chilliwack, BC), Harvey purchased property on Pearce Road, which had been the site of the RCAF Aerodrome Pearce, a Second World War training air station of the British Commonwealth. Here they began dairy farming in 1984 and in honour of the history of the site, named the farm Airport Dairy.” Photo: Bruce Forsyth

The old concrete hangar floor slabs from Pearce's days as a Second World War airfield now make great dry hay storage areas. Photo: Bruce Forsyth

No. 7 Service Flying Training School

Fort Macleod, Alberta

No. 7 Service Flying Training School (SFTS) at Fort Macleod began operations in December of 1940, with Alberta's long-serving Lieutenant Governor John Campbell Bowen in attendance. The school taught advanced flying to wings standard for pilots in the multi-engine stream—headed for Bomber, Coastal and Transport Commands of the RAF. The only aircraft employed at Fort Macleod was the Avro Anson. Administrative and operational control was the responsibility of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). No. 7 SFTS closed 17 November 1944 with the end of the war in sight and a declining need for bomber pilots.

A wartime aerial photo of Fort Macleod's No. 7 Service Flying Training School looking north with the fertile Oldman River valley rolling west to east in the distance. Photo: RCAF

After the war, the station itself remained open and hosted No. 1 Repair Equipment and Maintenance Unit (1 REMU), which was responsible for storing and repairing RCAF aircraft. Many of the RCAF's wartime Lancasters were put into storage here, pending their disposition. The station is now Fort Macleod (Alcock Farm) Airport. A few of the old station buildings used during the BCATP days can still be seen, but the bulk of the airport infield has been given over to a housing development.

A relief landing field for No. 7 SFTS was located near Granum, 15 kilometres to the north of the field. Today, Granum is unused but is one of the best-preserved examples of a paved triangular relief field in the country.

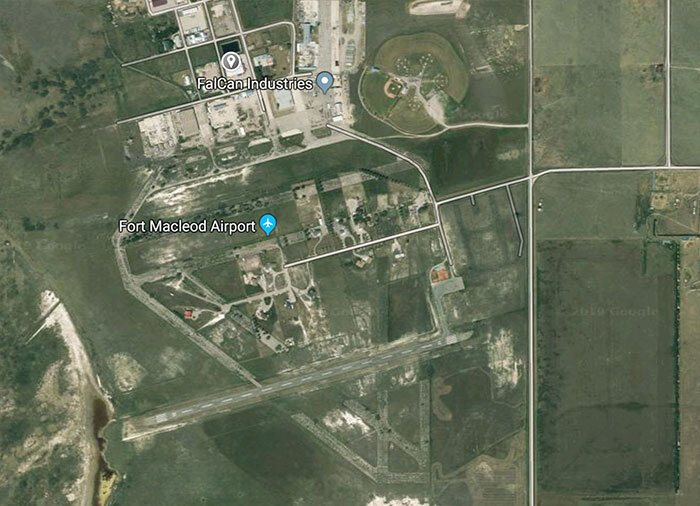

Warbird pilot Todd Lemieux circles the Fort Macleod Airport in the early morning in the summer of 2018, looking southeast. The original and classic triangular runway pattern can just be seen, but none of the runways is operational today, nor is any part of the original base. The new 3,000-foot runway (06-24) cuts across the southern apex of the old triangle. A housing subdivision now sits in the infield, surrounded by history. Photo: Todd Lemieux

Todd Lemieux circles Fort Macleod airfield in 2018. RCAF Station Fort Macleod had six runways in an overlaid triangle configuration. All of these runways were abandoned but can be seen clearly in aerial photography. Many wartime RCAF training stations had this triangle configuration in order to allow for takeoff and landing in a range of wind directions. The modern runway 06-24 is not one of the original runways. It was newly constructed approximately parallel to one of the existing runways, but cutting across the other four near their apex. Photo: Todd Lemieux

A satellite view of the Fort Macleod municipal airport today. Only the runway at the south end of the field functions today, but it was not one of the original runways of the wartime site. Image via Google Maps

Any relief airfield that had grass runways has now long ago faded into the earth, but many that had paved runways can still be seen scarring the wide prairie. Granum airfield is one of the most intact of these fossils, with its three asphalt runways clear and almost usable. The top photo, taken in 2018, shows Granum looking northwest with the village of Granum itself off in the distance along Highway 2. The bottom photo, taken in the spring of 2019, shows cattle roaming west of the field. Top photo: Todd Lemieux. Bottom photo: Lori Fitzgerald

Accidents, some fatal, were almost weekly occurrences on training bases across Canada in the Second World War. On 31 January 1941 at 0930 hours, two Avro Ansons on final at Fort Macleod collided with each other at a height of 50 feet. The two trainee pilots, LACs John Sully McKeown and John Boli, throttled their engines back and made a coupled landing (none of the four propellers appear to have been damaged). The bottom Anson (RCAF serial 6220), flown by McKeown, was damaged beyond repair and struck off charge with just 100 hours total flying time.

A pilot looks over the right nacelle at Fort Macleod aerodrome, top right. The utter flatness of the Southern Alberta prairie is striking. Since I can't see a pattern of fields, I suspect this photo was taken in winter with fields covered in snow.

A pilot looks over the right nacelle at Fort Macleod aerodrome, top right. The utter flatness of the Southern Alberta prairie is striking. Since I can't see a pattern of fields, I suspect this photo was taken in winter with fields covered in snow.

Members of H-Flight, Course 93 at No. 7 SFTS, Fort Macleod, pose before the beginning of their service flying training syllabus. Sergeant Mike Pawlowski of Spedden, Alberta, was killed 15 November 1944.

One of Fort Macleod's flying instructors was Flight Lieutenant William “Bill” Anderson. He lived off base with his wife and, in 1943, he and his wife Myrtle had a daughter named Roberta Joan. When that young girl began a life of music, she would change her name to Joni Mitchell and become perhaps the greatest singer/songwriter of all time—certainly, the finest to come from Canada. Following his RCAF career, Anderson moved to Saskatchewan, where he managed a grocery store and raised his daughter. He died in Saskatoon in 2012 at the age of 100! Myrtle passed away in 2007 at 95. Photo: Pinterest

Top photo: In 2004, when this photo was taken, one of the old barracks buildings on Primrose Avenue was in poor condition. Google Maps Streetview in 2019 (bottom photo) offers a close-up look at the present worsened state of the structure. Top photo: Bruce Forsyth. Bottom photo: Google Maps Streetview

The old taxiways and runways at Fort Macleod are well on their way to being subsumed by the prairie. Photo: Bruce Forsyth

A ramp-side view of one of the remaining hangars along the abandoned flight-line, taken in 2004. Today, the building remains much the same, but with windows boarded up. It is not known what use this structure is put to today. Photo: Bruce Forsyth

There were more Lancasters coming in from RCAF Scoudouc on the East Coast than could be accommodated at RCAF Pearce, Alberta. Many more were in semi-permanent storage at Fort Macleod, including this Lancaster X from 419 Squadron. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

The Lancaster ground maintenance crew at Fort Macleod, Alberta. Macleod was one of the former BCATP airfields where the Lancasters were dispersed, and though its first resident unit, No. 7 Service Flying Training School, had shut down in November of 1944, it housed No. 1 Repair Equipment and Maintenance Unit after the war, and a slew of Lancasters awaiting their fates. This greasy but happy crew were tasked with upkeep of the Lancs stored at Fort Macleod. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

In June of 1944, officers of the RCAF lead members of the Women's Division west down Main Street, Fort Macleod, in front of the Queen's Hotel. In the bottom photo, we see the scene as it exists today.

Flying from No. 7 SFTS (out of frame to the bottom), RCAF pilot Eddie Frisk took this photo of Fort Macleod during his time there in the Second World War. The Queen's Hotel can be clearly seen centre left. Photo: Eddie Frisk via Macleod Gazette

No. 5 Elementary Flying Training School

High River, Alberta

While most of the airfields were scouted, surveyed and built as part of the 1939 British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, some locations were already the sites of government-run or private airfields. High River was one of these. Wikipedia explains it history very well, so I am quoting that source here:

“The Canadian Air Board began operating the High River Air Station in January 1921 after having moved the station from Morley, Alberta, where the weather was discovered to be too erratic and dangerous for flying. In the early days, the station had an entirely civil function and was the largest in Canada with ten war-surplus aircraft that were part of the Imperial Gift provided to Canada by Britain after the First World War. In late 1922 when the Air Board and the fledgling Canadian Air Force was reorganized, operations at High River became the responsibility of the Canadian Air Force. And when the Royal Canadian Air Force was formed in 1924, the station became a Royal Canadian Air Force station: RCAF Station High River.

Most of the flying operations consisted of fire-spotting forestry patrols over the mountains and foothills to the west, which were flown by No. 2 (Operations) Squadron. The aircraft used was the DH.4. Late in 1924 Avro Vipers began to be used, and in 1928 de Havilland Cirrus 60 Moths were added. Initially, two patrols were made daily, to the Clearwater, Bow and Crowsnest Forest Reserves. One patrol flew north as far as the Clearwater River, and one south to the International Boundary. Eventually substations were built at Pincher Creek in the south and Eckville in the north to increase patrol efficiency. In 1928, a substation was constructed at Grande Prairie to enable the patrolling of the Peace River Country. Of the early Canadian air stations, High River was the most active, with 215 flights flown on forest patrols.

A Canadian Airco DH-4B (G-GYDN), part of the “Imperial Gift” (has there been a more condescending term?) of 114 surplus RAF aircraft, and operated by the Civil Operations Branch of the Air Board, taxies at High River in 1925. The aircraft, formerly RAF F2708, was taken on strength by the Air Board in 1921, converted for photo work, assigned to No 2 Operations Squadron at High River and struck off charge there in 1925. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

Other responsibilities of the station included aerial photography, parachute experimentation, aircraft testing, and aerial pesticide spraying. In the early 1920s the station became involved with experimenting with radio. Wireless equipment was developed in cooperation with the Canadian Corps of Signals to develop radio signals to be broadcast over distances greater than 300 km. The most powerful radio transmitter in North America began operating from the High River Air Station in 1922.

After jurisdiction for natural resource management was transferred to the Province of Alberta in 1930, fire towers were built and spotting aircraft were no longer necessary. Fire-spotting patrols gradually ceased. Other activities such as aircraft testing continued until the station closed on March 31, 1931. The station did, however, remain as an aircraft storage facility until the beginning of the Second World War when the station was reactivated to train pilots for wartime service.

No. 5 Elementary Flying Training School

RCAF Station High River was a major participant in British Commonwealth Air Training Plan aircrew training during the war. No. 5 Elementary Flying Training School was established at High River in 1941 using civilian instructors from the Calgary Aero Club. De Havilland Tiger Moths were the first aircraft used. They were later replaced by Fairchild Cornells. An unprepared emergency and practice landing field, also known as a relief landing field, was located on the then dry lakebed of nearby Frank Lake.

An aerial of High River looking northeast from the wartime. Today, the four lanes of Alberta's divided Highway 2 scar the landscape, but it 1942, there was nothing but farmland to the horizon. Photo: RCAF

I had to adjust the contrast and hue of this screen capture from Google Maps to bring out the faint outlines of the old familiar runway pattern. Today, only a single Second Wold War vintage hangar still stands, used by a building contractor. Image via Google Maps

A very rare shot of Tiger Moth training aircraft being maintained in a hangar other than the standard RCAF structures designed specifically for the BCATP. These smaller hangars were built at High River in 1921, when the High River Air Station opened. The Canadian Air Board began operating the High River Air Station after having moved the station from Morley, Alberta, where the weather was discovered to be too erratic and dangerous for flying. In the early days, the station had an entirely civil function and was the largest in Canada with ten war-surplus aircraft that were part of the “Imperial Gift” provided to Canada by Britain after the First World War. In late 1922 when the Air Board and the fledgling Canadian Air Force was reorganized, operations at High River became the responsibility of the Canadian Air Force. And when the Royal Canadian Air Force was formed in 1924, the station became a Royal Canadian Air Force station: RCAF Station High River (Wikipedia). These old hangars were a design from the First World War known as Bessonneau Hangars and were transported to Canada along with the “Imperial Gift” of aircraft and assembled in Alberta. Tiger Moth 4972 suffered Category C damage in an incident at High River in September of 1941, so likely this is an image of it being repaired. Note the car sharing the hangar with the Tigers. RCAF Photo via http://www.timothyallanjohnston.com

Two High River-based Tiger Moths fly across the Southern Alberta landscape. Can you spot the problem with this photo? Well, single pilot operation of the Tiger Moth should always be from the back cockpit, yet this student or instructor is sitting alone in the front. Perhaps he has cargo in the rear cockpit. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

De Havilland D.H.82C Tiger Moth, serial number 5091 spun and crashed after takeoff at 20:00 hrs, on 13 May 1942. The aircraft came down 5 miles north of High River aerodrome. One of Gordon Jones’ fellow instructors, Flight Sergeant Phillip Hayne Chapman was killed and his student, LAC R.B. Thompson seriously injured. The accident reports states: “A/C took off with Sgt. Chapman in front seat giving instruction to LAC Thompson. Shortly after a/c made a gentle turn to the right then went into a spin to the right and continued to spin until it hit the ground totally damaged. Propeller was not turning when a/c crashed. Though injured, Russell Bennett Thompson, of Winnipeg, went on to complete his training and to join 158 Squadron as a Pilot Officer. Sadly, he lost his life on the night of 2–3 June 1944 on ops to the French city of Trappes, southwest of Paris. He is buried in the Ecquetot Communal Cemetery in the town of Eure.” Photo via Museum of the Highwood, High River, Alberta

A shot of Tiger Moths at High River during the war. All of them have their coupe-top canopies for cold weather flying, a necessity in Alberta winters. This was likely taken in the springtime before the weather warmed enough aloft to remove the canopies which would have been uncomfortably warm in summer. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection`

An early shot of the EFTS at High River with only the single BCATP hangar finished along with the three older pre-war Bessonneau hangars. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A great airside shot of High River looking west toward the Rockies, just visible on the horizon. The pre-war “Bessonneau” hangar line is on the right and the ramps are filled with dozens of new Fairchild Cornell elementary trainers and one twin-engined aircraft, possibly an Anson at left.

Another view of the High River aerodrome, this time looking east. Though the quality of the scan is poor, I suspect it was taken at the same time as the previous photo as the twin-engine aircraft is still there in the flightline (top) with 11 Cornells lined up to the left—same as the previous image. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

A typical class from No. 5 EFTS High River—Course 92, “E” Flight. Since none of the students have their wings, this photo was likely taken when E flight was formed during Course 92 Photo via Anne Gafiuk

During the war, ladies of the RCAF's Women's Division are seen gathered at No.5 EFTS at High River. Judging from the number of women in this photo, they are all here possibly for some course, as there usually would not be this many on one station. This looks like the same spot as in the previous photo, with similar benches. Perhaps this was the preferred group photo location on station. Women were critical to the operation of a flying training station like High River, performing a wide range of administration, transport, parachute rigging and maintenance work. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection

The last of two original Second World War hangars of No. 5 EFTS, High River, now houses equipment and storage of a home building company. Photo: Don Molyneaux

Inside the more than 70- year old hangar, the wood structure looks in relatively good condition. This photo shows us just how much light the hangar's windows bring in, as there are no electric lights on in this interior shot. Photo: Don Molyneaux

One of the great legendary characters of No. 5 EFTS was flying instructor Pilot Officer Gordon Jones. After the war, Jones lived in the High River area and maintained a vintage de Havilland Tiger Moth at the High River Airport—one he actually flew at No 5 EFTS! Jones’ de Havilland Tiger Moth was originally one of 200 ordered and built for the United States Army Air Corps, designated PT-24 DH (Serial Number 42-1078). Then it was listed as a Lend Lease aircraft with RAF serial number FE214 and then sent to High River as RCAF 1214. Photo via Anne Gafiuk

A group of flying instructors known as the “High River Clan” and their wives: Ralph and Lois White, Ernie and Goldie Snowdon, Bob and Marie Spooner, and Linora and Gordon Jones. Photo via Gordon Jones Collection

In the previous map, we can see the Frank Lake relief field for High River, southeast of the town. Frank Lake was a very different kind of landing field than all other BCATP airfields— a series of shallow alkaline lakes that were bone dry in the 1930s and 1940s after the Dust Bowl weather of the Great Depression. Instead of building a standard relief airfield, the RCAF simply used the flat dry lake bed as a landing field. It is not known if there were any structures. Today the lakes are no longer dry and are controlled by Ducks Unlimited Canada for wildlife management purposes. The water in Frank Lake is treated waste water from High River and from a nearby meat packing plant piped in. Not conducive to swimming I imagine. Top photo: Todd Lemieux, Bottom: Lori Fitzgerald

A great diorama of No. 5 EFTS High River at the height of its contribution to the war effort. This wonderful diorama was built by Larry, Debra and Bryce Kunz St. Gregor, Saskatchewan.

A Tiger Moth instructor and student at High River.

No. 31 Elementary Flying Training School

De Winton, Alberta

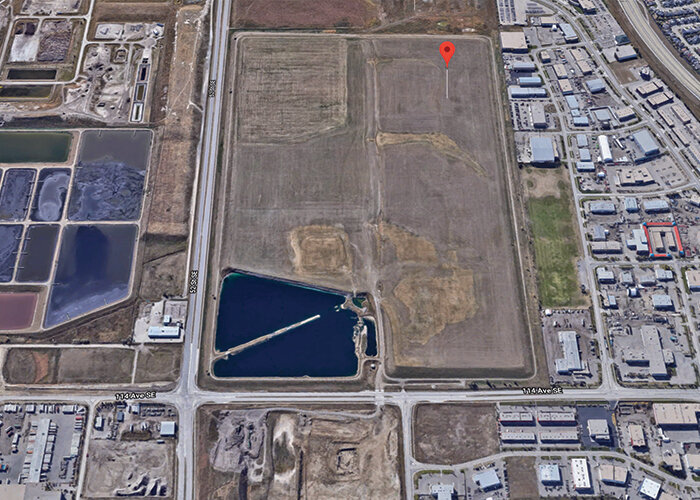

In the summer of 1941 when the aerodrome at De Winton was opened, the city of Calgary's edge was perhaps 20 kilometres to the north. Today, the site of De Winton is now the outskirts of a much larger city. It was named for the nearest community—the village of De Winton, some 13 kilometres to the west. It was the home to one of the BCATP's most successful elementary flying training schools—No. 31 EFTS. The aerodrome was one of several under the command of the Royal Air Force in Alberta, but the flying training carried out here was done under the auspices of the Malton Flying Training School (Toronto Flying Club), which also operated No. 1 EFTS at Malton, Ontario. The school operated two Relief Landing Fields—a grass runway field at Gladys, 11 kilometres to the southeast, and a larger one with asphalt runways at Shepard, some 20 kilometres to the northwest.

De Winton was one of the most successful flying training schools in the British Commonwealth and was awarded the Royal Air Force's “Cock O'the Walk” award as the best-run flight training school in the entire Commonwealth. With victory in sight, the RAF closed De Winton and its relief fields in September 1944. The abandoned airfield is now the privately operated but largely unused De Winton/South Calgary Airport.

Although the runways and some structures from the original EFTS remain, the airfield is no longer active for fixed-wing use. Some helicopter training, such as auto-rotation and hover practice, is still performed at the airfield, but all flights originate from other airports. The Calgary Ultra-light Flying Club used one runway for “touch & go” training for student pilots for a period, but does not currently use the airfield. For several years, the abandoned runways were used as a racetrack for sports car and motorcycle racing. Today, two of the runways are in disrepair and overgrown with grass, while the third runway is only partially maintained for use as an automotive driver training area.

Dozens of Stearman Kadet aircraft line the ramps of De Winton in 1942. Photo: RCAF

The airfield now has a permanent commemorative plaque that tells the story of those brief but heady years during the war. Bruce Forsyth tells us about the recent commemoration ceremony:

“On 15 June 2016, close to 200 people gathered at the De Winton airfield to commemorate the 75th anniversary of No. 31 Elementary Flying Training School, during which a bronze plaque commemorating the school was unveiled. Guests at the ceremony included Flight Lieutenant James Andrews from the Royal Air Force; Dr. Stéphane Gouvrement, a historian and honorary colonel of 419 Tactical Fighter Training Squadron; Susan Cowan, the daughter of one of the school’s commanding officers; and Squadron Leader Rae Churchill, a former Second World War instructor at RCAF Station Bowden.”

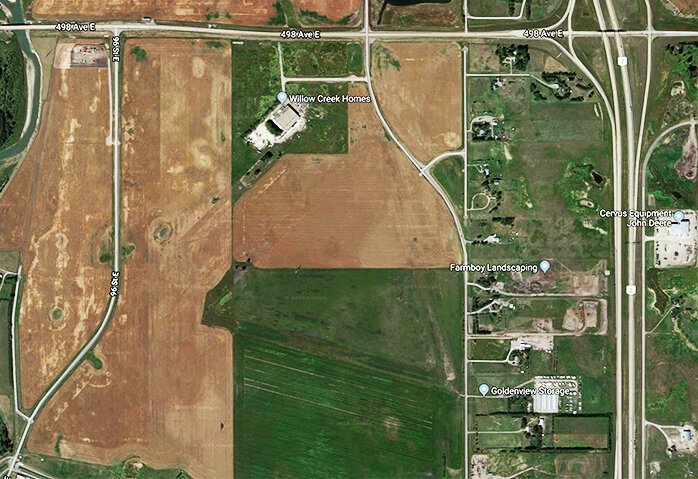

Forsyth also tells us what happened to the relief field at Shepard:

“As for RCAF Detachment Shepard, the abandoned runways were used as a racetrack for sports car and motorcycle racing, known as the Shepard Raceways, from 1958–1970 and then the Calgary International Raceway in the mid 1970s. The former north-south runway was used as a drag race strip until it closed around 1983, when the construction of Deerfoot Trail cut across the old runway. The Alberta Motor Association then used the runway as a driver training facility. The SE-NW runway and east-west runways were torn up in the early 1970s with construction of Shepard landfill. Today, nothing remains of the Shepard Detachment. In the early 2000s, the remaining property was redeveloped into an industrial complex. A “Flying J” truck stop now occupies part of the property where the airfield used to be. Nothing remains of RCAF Detachment Gladys.”

Occupying a flat expanse of land near the confluence of the Bow and Highwood Rivers, De Winton's No. 31 EFTS must have seemed like the middle of nowhere to the Royal Air Force student pilots who came from Great Britain. It was named for the nearest community in 1940—the hamlet of De Winton, some 12 kilometres to the west. Today, the southernmost suburbs of the city of Calgary are beginning to encroach. Image via Google Maps

Today, only the runways, taxiways, ramps, and floor slabs of the hangar line remain from the old No. 31 Elementary Flying Training School. The airport was still functioning as the “De Winton/South Calgary Airport” with only a single runway in fair enough shape to land aircraft. The airport has been closed for a number of years. The only remaining structure from No. 31 EFTS is the concrete gun butts—seen here as the deeply shadowed structure to the left of the two hangar pads. During the 1970s and 80s, the runways and taxiways were used for safe-driving courses and auto racing. Image via Google Maps

Lemieux and Fitzgerald visit De Winton in early June of 2019 and capture the silence and emptiness of the once-teeming aerodrome. The Bow River snakes away to the southeast in the upper corner. Photo: Lori Fitzgerald

Lemieux circles to the north of the field, with the Bow River at upper left. In the distance the Highwood River valley comes into view on the right. The yellow arrow points to a small cluster of buildings that is a permanent western town movie set known as Albertina Farms. The Netflix period-piece series Damnation, set in the 1930s, was filmed here along with many other films and TV scenes from series such as such as Hell on Wheels and Fargo . The fictional town is set in the valley so that there are no modern visual distractions in the background. As a result, the “circus,” that large caravan of trailers, tents, cafeterias, and generators that accompanies large productions, was always assembled on the airfield, out of site on the plateau above the valley. Some scenes from Fargo were shot on the airfield itself as well. Photo: Lori Fitzgerald

The town of “Albertina—a film production set that sits in the Highwood River Valley south of the former De Winton airfield. Photo: Lori Fitzgerald

Twelve yellow Stearman Kadet trainers are lined up next to a hangar at De Winton in the fall of 1942. De Winton's No. 31 EFTS was a Royal Air Force flight training school, one of several in Alberta. As such, it was also one of the three BCATP schools in Alberta to offer elementary flying instruction on the Stearman Kadet. The Royal Air Force purchased 300 Kadet aircraft and began training at No. 31 EFTS De Winton, No. 32 EFTS Bowden, and No. 36 EFTS Pearce. The Stearman Kadet was a much-loved and excellent training aircraft—until winter arrived! The open cockpit Kadets did not arrive with the planned winter equipment, the most important of which was an enclosed cockpit. Flying in an open cockpit aircraft in an Alberta winter was a misery one can only imagine. Despite these problems, they were employed until the much better equipped Fairchild Cornell trainers could be supplied. Pennie and his fellow students considered themselves amongst an elite group of BCATP airmen who trained on the Stearman Kadet—a larger, more powerful biplane than the Tiger Moths and Fleet Finches also in use at the time. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection and Tim Johnston

For the men and women who operated the airfields of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, the metrics of success were men trained, aircraft serviceable, accident-free days, and runways operational. To fly the “E” pennant for efficiency from the staff at the front gate was to show that the efforts you made to the war effort had achieved important results. The Efficiency Pennant was like a Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for an organization. Here, the Efficiency Pennant is held aloft by Mr. E. O. Houghton, manager of the Malton Flying Training School (the Toronto-based civilian operator of No. 31 EFTS) and Air Vice-Marshal G. R. Housam RCAF, air officer commanding No. 4 Training Command. Looking on is Squadron Leader R. E. Watts RAF, base commander. The date is 27 May 1943. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection and Tim Johnston

Another angle on the raising of the RAF's Efficiency Pennant at De Winton with Houghton, Housam and Watts at right. in 2015, this very flagpole was discovered laying in the long grass at De Winton and salvaged by a team from the Bomber Command Museum of Canada (BCMC). Photo: Bomber Command Museum of Canada

A team of volunteers from the Bomber Command Museum of Canada (BCMC), headed by Tim Johnston recovered the De Winton flag pole in 2015. According to the BCMC, “a round piece of wood caught Tim’s eye through the tall grass. As he brushed away more of the grass to expose its full length and three large clamps, it became obvious that this could only be RAF De Winton’s flagpole -simply the thirty-three foot long trunk of a Douglas Fir, painted white. Tim recalled having seen the flagpole as the focal point in a photo of station personnel assembled on 31 EFTS’s parade square as officers proudly raised an ‘Efficiency Pennant’ on 27 May 1943. It was a very special day for the school as their School was being recognized as one of the very best in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. There it was, almost completely hidden in the tall grass and rotting away.” Photo: Bomber Command Museum of Canada

Today, the fully-restored De Winton flag pole hands on the wall at the BCMC, awaiting some future and higher purpose. Photo: Bomber Command Museum of Canada

At the same time he awarded De Winton the Efficiency Pennant (previous photo), Air Vice-Marshal G. R. Housam RCAF, air officer commanding No. 4 Training Command, also presented the flying school with the the RAF's “Cock O'the Walk” award, stating, "Your station has been awarded the Minister's Pennant and in addition the 'Cock O' The Walk' trophy as being the most efficient elementary flying training school in the British Commonwealth Air Training Scheme and the winning of the double award means much. You have achieved the highest standard of efficiency of any elementary school in the world and there is no other flying training organization compared to your own." That's saying something given the high quality of every facility in the BCATP. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection and Tim Johnston

No. 31 EFTS De Winton put together an elaborate float in the 1943 Calgary Stampede parade. The theme of the float was “We teach the world to fly.” On the side of the float are listed the countries from which its students had come—China, Czechoslovakia, Ceylon, Canada, Great Britain, France, Netherlands, Australia, Denmark, Poland, Norway, Tahiti, South Africa, New Zealand, West Indies, United States, Russia, Belgium. At the front of the float are the flags of Canada, Great Britain, and the USA and above those, the Efficiency Pennant. The flags at the back appear to be those of Australia, New Zealand, and possibly Norway. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection and Tim Johnston

Squadron Leader Ronald E. Watts of the Royal Air Force (third from left in front) poses with his administration staff. By the look of things, it was a cold day at De Winton. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection and Tim Johnston

Like all BCATP bases, De Winton was a source of much local employment, needing many civilian workers from the surrounding area to carry out myriad tasks—from kitchen work to transport and maintenance to administration. Here four young ladies (left to right: Connie Eastcott, Evelyn Patterson, Isabelle Hall, and Jean O'Leary) from nearby Okotoks, Alberta, in crisp white coveralls pose at De Winton on a bright summer day. Photo: Connie Eastcott Bodkin Collection

The great Albertan fighter ace, Lieutenant General Don Laubman, DFC and Bar, AOE, CD and 2 Bars was, for a time, a flying instructor at De Winton. Laubman, whose personal tally from the war includes 15 destroyed and three damaged, was born in Provost, Alberta, and got his wings at No. 3 SFTS Calgary. Laubman did his Flying Instructor training at Vulcan, Alberta, before serving at De Winton. Following his time at De Winton, Laubman served with 133 Squadron RCAF on the West Coast as part of the Home War Establishment. He then went overseas where he was posted to 412 Squadron, the same unit that John Gillespie Magee had served with before he was killed. Laubman was shot down on his second tour, commanding 402 Squadron. He became a prisoner of war... but for just a few weeks as the war was almost over. Photo: RCAF

De Winton soldiered on after the war as an auto racing track—the fate of more than one former BCATP base. Later is was reopened as a small private airport known as the South Calgary Airport. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada Collection and Tim Johnston

In June 2016, a brass plaque commemorating De Winton's extraordinary contribution to the war effort was unveiled on the 75th anniversary of the school's opening, with an officer of the Royal Air Force in attendance as well a veteran BCATP instructor: Squadron Leader Rae Churchill, and Susan Cowan, the daughter of the base's former Commander, Squadron Leader Ron Watts. The plaque reads in part: “Formed at Kirkham, England on April 16, 1941, this school was one of six Royal Air Force (RAF) elementary flying training schools (EFTS) sent to Canada to train British aircrew. These and other RAF schools in Canada operated alongside the schools of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCAT) and graduated 5,296 aircrew prior to the reorganization of the Plan in July 1942. Canada was the lead nation in the BCATP, a massive undertaking that saw 131,553 aircrew graduate from 110 training schools. During its operational life, No. 31 EFTS De Winton trained aircrew from 20 free or occupied countries including the United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, France, Czechoslovakia, Norway, Poland, Belgium and Holland. Under the terms of the reorganization, this school, along with all other Royal Air Force schools in Canada, was fully incorporated within the BCATP. The Toronto Flying Club took over management of the school with flying instructors provided by the RAF until the school’s closing on August 26, 1944. De Havilland Tiger Moths were the first training aircraft used on the base. Supplementing these were Stearman PT-27s provided to Great Britain by the United States through the Lend-Lease Act. Following the return of the Stearmans to the United States, the school eventually transitioned to Canadian-built Fairchild Cornells. No. 31 EFTS De Winton was recognized for its outstanding performance by the award of the Efficiency Pennant on April 30, 1943. On May 7, 1943, under command of Squadron Leader R.E. Watts, the school was awarded the “Cock of the Walk” trophy in recognition of having achieved the highest standard of efficiency of any elementary flying training school in the British Commonwealth. Placed on June 15, 2016, this memorial is dedicated to the memory of those who trained and served at No. 31 EFTS De Winton and to those who made the supreme sacrifice in defense of their countries and democracies.” Photo: Anne Gafiuk