SKIS AND FLOATS — Anything but Wheels

Here in Canada, when you meet a pilot who owns his or her own airplane, it won’t be long before you ask him or her, “You on floats, amphibs, skis or wheels?” There are not too many countries in this world where this is a relevant question—the Northern US and Alaska, and possibly Scandinavian countries. If you fly in Canada as a general aviation pilot, you do a lot of your flying over dihydrogen-monoxide—the liquid, solid and powdered forms of it.

In summer, flying over some areas of Northern Ontario or Québec, there aren’t too many places to put down in an emergency if your gear is made of rubber and is circular—but there is plenty of water. In the warmer months in the north of Canada you would be smart to have floats or amphibious gear bolted to the bottom of your airplane—for safety and for freedom—freedom to put down in any lake big enough to get out of. Free to throw a fishing line in a lake that hasn’t seen an angler in 20 years. Free to visit a friend’s cottage in the spring without getting mired in the muck. Floats make you free!

When you fly on wheels in the summer, you are well advised to keep a constant vigil for places to land in an emergency. Winter is another story. In winter, an airplane on skis is forever over a landing field. If your engine decides that it no longer wants to continue its work in -40C, if you smell smoke or if your propeller sheds a blade, all you have to do is let down and turn into the wind. Mind the fences. Short of a catastrophic structural failure, flying on skis is a safety feature that will save your life.

On skis, you can visit “Les Boys” at a river ice fishing village for some “hot dogs steamés” and “fèves au lard” (Rhum and Pepsi if you plan to stay the night), you can visit your Saskatchewan rancher buddy and pull up in the lower 40, or, if you have to just take a piss... right now... right here, skis give you a better option than a pickle jar.

The joy of winter flying... taking off in cold dense air, directly into the wind and bound for ski-plane adventure. Photo: J.P. Bonin

You ask any Canuck pilot what he or she prefers—wheels, skis or floats and the answer will likely be:

Anything BUT Wheels

Despite researching material over the past eight years for the more than four hundred stories, albums, features and missives of Vintage News, I am still in awe of the historical, emotional and visual matrix that is the World Wide Web. While I am well aware that the web is not a universe of truth, fact, scholarly wisdom and purity of intent, it still astounds me every day for its ability to deliver to my hungry eyes images, stories and stored memories of humanity’s recent and sometimes cataclysmic history.

In particular, it is my wont to follow leads and key words to find information and images that support our stories of Canada’s aviation heritage and the heroes who populate this extraordinary and courageous legacy. I am, not weekly, not daily, but nearly every minute amazed by the images that I come across whilst researching a story’s background. More than likely these photos may have nothing immediately to do with the story I am background checking. For a couple of years, I just gawked like a Sunday driver passing an accident scene and then moved on, but a number of years ago, I opened a folder on my computer’s desktop which I called Random Beauty, and into which I dragged the images that caught my eye. Soon, there were hundreds of these digital images and Random Beauty became a recurring feature of Vintage News, sharing with our readers those riveting and sublime photographs found serendipitously and, with apologies, lifted.

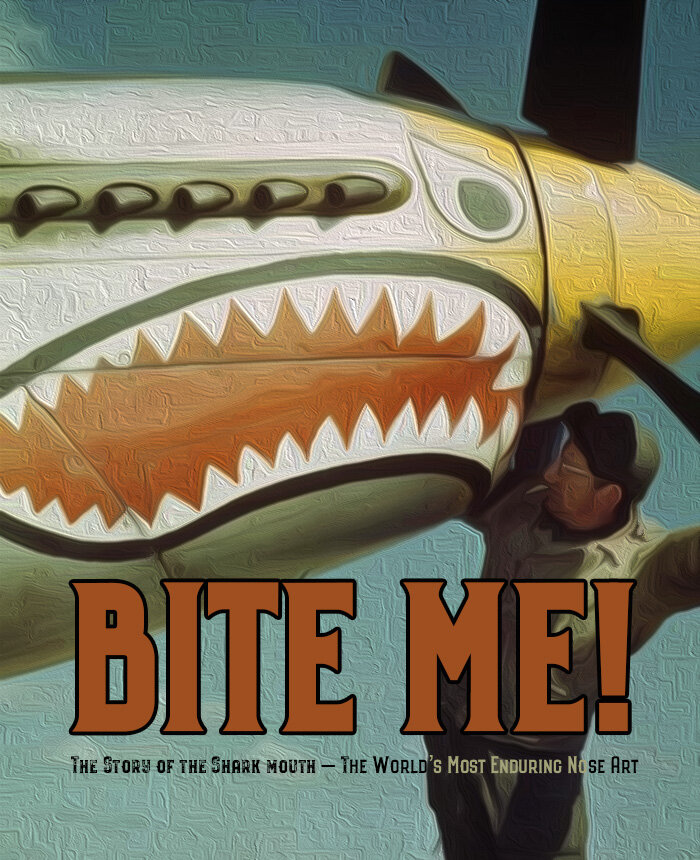

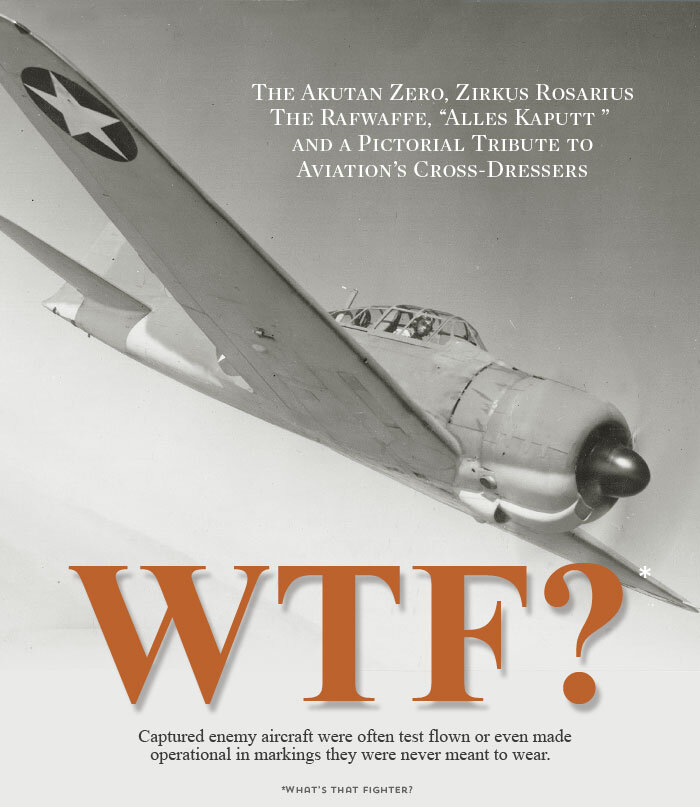

Over the past years, I have divided this folder into a number of sub-categories with the intent of collecting images which were linked by theme or of a similar subject—until a critical mass was achieved and from this, a story or feature might possibly emerge. I have folders with titles such as Large Aircraft Formations, WTF?, Burning Aircraft, Bad Taste Nose Art, Heroic Portraits, Martin Marauder, or Vintage Aviation Advertising. A few years ago one of those folders, Low Flying, reached this critical mass and spawned a story entitled Lower Than a Snake’s Belly in a Wagon Rut that went viral around the world and netted our website more than 100,000 visits in two months. Before that, another called The Squadron Dog told the story of the curs, mutts and pedigreed pooches that have permeated air force operational history since Orville and Wilbur and the Saint Bernard they called Scipio. Now, another of these collections, a folder called Anything BUT Wheels, has matured, grown fat and gestated enough for me to wring from it a story... or rather a cultural and visual compendium.

To qualify to be saved to the Anything BUT Wheels folder, a photo had to be of a military/combat aircraft on floats or skis that was NOT designed from the get go as a float plane, flying boat, or bush plane. I started with fighter aircraft, but soon branched to military aircraft of all sorts—except purpose-built float aircraft. The folder first contained images of Spitfires on floats and P-51 Mustangs on skis, but soon there were trainers and the odd transport aircraft (though these had to be military transports). I wanted to explore the one-offs, the failures and the successes, not for any other reason than that it was, well... cool.

Related Stories

Click on image

Reading through material connected with each photo, I found it was rare for a combat aircraft (fighter, dive bomber, torpedo bomber) to be outfitted with pontoon floats and be a success... except in the case of certain Japanese fighters such as the Mitsubishi A6M Zero turned into the Rufe float plane. Most of the Second World War fighters were a perfect collection of optimized ideas, years of aerodynamic study and a whole lot of just plain style. There was no consideration in their creation of how they might work on floats and, in most cases, bolting on to their undersides two massive sealed aluminum fuselages led to the scrap heap. When it came to floats, the Japanese were the hands-down winners. When it came to skis, it was the Scandinavians and the Russians.

Perhaps in the case of ski planes and float planes, it was necessity that made them a success. The Japanese could not possibly protect their massive and far-flung empire without float planes—thousands of islands, some not big enough for an airstrip or too far away to construct one economically. They opted for float plane fighters, and though they may not have had the widespread early successes of their land and carrier based relatives, they held their own.

In the land of the midnight sun in the 1930s, the Finns had a lot of mistrust for the Soviets and long before the first of their two wars against the Soviets between 1939 and 1944, they readied themselves by developing ski-plane technology. Having aircraft on skis debilitated the performance of their aircraft somewhat, but the ability to disperse aircraft on frozen lakes and snow covered meadows enabled the Finnish Air Force, the Ilmavoimat, to hold their own against the Soviet juggernaut. The Finns hated the Soviets so much that they supported the Germans during their invasion of the Soviet Union. Though they had not signed the Tripartite Pact (Germany–Italy–Japan), they were deemed an enemy by the Allies who largely left it up to the Soviets to deal with them. The Finns fought the Soviets in the Winter War (the winter of 1939–40) and the Continuation War from 1941 to 1944 and the Communists failed to best them. Though Sweden claimed to be neutral, it did in fact send a secret air force unit called F-19—aircraft, aircrew and ground support—to fight alongside the Finns during the Winter War. All three air forces (the Finnish Ilmavoimat, the Swedish Flygvapnet and the Soviet air force) made use of ski-plane technology not just experimentally, but at squadron strength.

Fighters on Floats

This collection of photographs culled from the World Wide Web is by no means complete. I am sure there are other combat aircraft, military trainers and transport aircraft that qualify for inclusion, and I encourage you to send them in. The only stipulation is that they should not be designed originally as a float plane or flying boat. So, let’s get the show on the road... or rather, on the water.

Prior to the development of the Hurricane, Hawker Aircraft was a producer of some of the finest and fastest biplane fighter and light bomber aircraft of the interwar period—the Hawker Hector, Hardy, Hind, Nimrod, Hartbees, Hornet, Osprey, Audax, Demon, Fury, Super Fury and Hart. Nearly all were powered by Rolls-Royce V-12 engines like the Kestral. The Estonian Air Force purchased 8 Hawker Harts in 1932, four with floats, four on wheels. The float-equipped four were used in coastal defence by the Independent Naval Air Flight, but when this unit was disbanded, the float planes reverted to wheels. Photo: GoPixPic.com

Two Hawker Harts of the Independent Naval Air Flight of the Estonian Air Force (No. 151 in foreground, and just visible behind, another). Photo: Aeroflight.co.uk

No one did float plane combat aircraft better than the Japanese Imperial Navy. With an empire stretched thin across millions of square kilometres of the Pacific Ocean, and a Navy that could not be everywhere at once, the Japanese took the art of the float plane and the flying boat to the highest levels. Many distant outposts were too small for landing strips or too far away to economically construct one. Japanese fighter aircraft like the Mitsubishi A6M Zero held the upper hand for the first part of the war, and its slower float plane development, the Nakajima A6M2.N (Rufe) had some success. Deployed in 1942 defensively in the Aleutians and Solomon Islands, they were effective against PT-boats on night operations. Here a flight of five Rufes makes an impressive sight. Photo via RCGroups.com

A pair of Mitsubishi/Nakajima Rufes in flight. The Japanese seemed to favour the centreline float with wing outriggers. The A6M2-N float plane was developed from the Mitsubishi Zero and was designed to support amphibious operations and defending remote bases. Photo via airpages.ru

If there is one photograph which demonstrates the commitment of the Japanese Imperial Navy to the float plane fighter concept, this is it. While this looks more like a beach front tiki resort than the Bougainville fighter base, we count seven Nakajima Rufe fighters ready for action, lined up like rental jet skis. Photo via zhjunshi.com

The Kawanishi N1K Kyofu (Allied code name Rex) was perhaps the hottest looking float plane of all time—a fighter grafted to a submarine. It was originally built as a float plane fighter to support forward offensive operations where no airstrips were available. This story is about combat aircraft converted to floats and skis. The “Rex”, purpose-built as a float plane does not qualify, but the conversion in this case went the other way. By the time this aircraft entered service in 1943, the war had shifted to defence and super-hot float plane had lost its importance. The Rex was then converted to a wheeled fighter, named George by the Allies. Photo: IJNAFPhotos.com

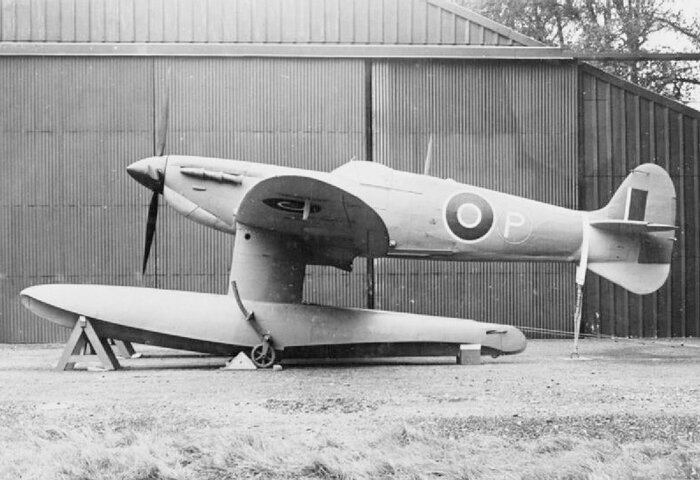

One of the greatest looking float planes of all time, something that Mike Potter should consider for the cottage—the Supermarine Spitfire on floats. During the Norwegian campaign in 1940, when the British were attempting to drive the Germans from the west coast of the Scandinavian Peninsula, they were at a severe disadvantage to the Germans in that they had no access to airfields in the war zone. Short-legged fighters like the Spitfire and Hurricane could not operate from Scotland and still have usable time over Norway. The British Air Staff put out an emergency request to develop float plane versions of both the Spitfire and the Hurricane. The first attempt, by Folland Aviation, a major subcontractor to Supermarine supplying most of the rear fuselages for Spitfires, utilized a Spitfire Mk I and the floats from a Blackburn Roc. The mashing together of the Roc and the Spit was called the Narvik Nightmare. Before it could be properly tested, the Germans had taken control of Norway and the need for a float plane fighter had faded. Photo via tumblr

The B-25 Roc was a ship-based carrier aircraft built by Blackburn Aviation. The wheeled version proved to be entirely inadequate as a fighter aircraft (only one victory was ever recorded by the type), and the float-equipped variant was even worse. The floats designed for the Roc, however, were to be utilized for the one-off Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I float plane known as the Narvik Nightmare. Converting a combat aircraft designed for wheels to float configuration was shown to be often wrong-headed right from the start, but militaries persisted all throughout the war. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Despite the low priority for Spits on floats after the Norwegian campaign, Folland continued to play with the concept and in 1942 began testing a series of Spitfires modified with custom designed, high speed floats. In addition to the floats, the Spit sported a four bladed propeller and a highly modified tail, bearing little visual connection to the tail we have all come to know. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The first flight of a Spitfire float plane (W3760) took place near Southampton and showed that a larger ventral fin was needed. Further tests were flown near Glasgow, Scotland. Despite the mass of the floats, the aircraft weighed only 1,100 lbs more and the topside speed was reduced by only 40 miles per hour. The aircraft was surprisingly nimble despite the floats and test pilots were of the opinion that it could be a front line aircraft flown by line pilots. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Two photos of Supermarine Spitfire Vb (W3760) taxiing on water. The photo at bottom, taken first, is different in that a Volkes filter (enlarged chin intake) was added to the carburetor air intake for the first tests. As well, we can see that the tail is largely the same as standard Spitfires except for the ventral fin. In the photo above, we can see that the Volkes filter intake has been changed to the Aero-Vee filter, similar to those found on later series Merlin-powered Spitfires. Also evident is the enlarged vertical stabilizer and rudder, added to gain back some directional authority. Photos: Imperial War Museum

Spitfire Vb EP751 looks strange indeed plowing through the salt waters of Great Bitter Lake in Egypt. Three float plane conversions (W3760, EP751 and EP754) were transported to Egypt for testing. It was hoped that if tropical operation tests proved successful, more Spits could be converted for operations from concealed bases in the Dodecanese Islands, disrupting German supply lines. However, the battlefront had shifted with the German capture of Kos and Leros, and no role could be found for the Spitfire float plane. The three aircraft languished in Egypt.

One last kick at the can. Spitfire Mk IX (MJ892) being tested in Great Britain. In the spring of 1944, it was thought that the Spitfire float plane idea might yet still have life, with the possibility of facing war with Japan after the Germans were finished off. Test pilot Jeffrey Quill said of the Mark IX: “The Spitfire IX on floats was faster than the standard Hurricane. Its handling on the water was extremely good and its only unusual feature was a tendency to ‘tramp’ from side to side on the floats, or to ‘waddle’ a bit when at high speed in the plane.” It wasn’t long before the idea was scrapped for good and MJ892 was converted back to wheels. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The Grumman F4F-3S Wildcat (BuNo 4038), jokingly referred to as the “Wildcatfish”, was an investigation into the viability of converting the little barrel-like ship borne fighter to a fighting float plane using Edo floats. The large ventral strake and tail plane fins were added to restore lost stability. Photo: US Navy

The Wildcatfish (without the ventral fin), was first flown on 28 February 1943 and the results were less than promising. The heavy floats were so draggy, they reduced the maximum speed of the Wildcat from 320 to 281 mph. Given that the main Japanese fighters like the Zero already had better performance than the Wildcat, the benefit of the floats was far outweighed by the fact that it was a sitting duck.

A United States Navy Curtiss SB2C Helldiver leaps into the air from a choppy sea in September of 1943. The caption attending this photo indicates that it was “Take Off No. 6”. The Helldiver was a carrier based dive bomber, many of which were made under licence in Thunder Bay, Ontario. The fifth production aircraft (BuNo. 00005) was modified with two floats and a large ventral fin to become the XSB2-C Helldiver Seaplane. The Navy was considering purchasing up to 350 of the type. The second prototype was lost in water tests and the programme cancelled. Photo: US Navy

While the Curtiss Helldiver XSB2-C2 Seaplane was a poor performer, it was an impressive looking aircraft, standing on amphibious floats. Note the “hydrovane” below the tail, offering increased lateral stability. Only the one prototype and a single SB2C-2 production aircraft were built. The second one was lost in tests. Photo: US Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation

The Curtiss Helldiver was not the only United States Navy carrier-based combat aircraft that received floats. One Douglas TBD-1A Devastator, the only other variant of the poorly performing torpedo bomber is seen here in Rhode Island undergoing torpedo testing with a high visibility torpedo slung beneath. During the Battle of Midway, the wheeled production of the Devastator proved to be utterly inadequate in terms of manoeuvrability and speed, so it doesn’t take much imagination to picture how inadequate the single float-equipped variant was. In this photo, it is difficult to tell whether the propeller is spinning or removed. Photo: US Navy

The Vought SB2U Vindicator was the first monoplane dive bomber of the United States Navy, coming into service in 1937. In Royal Navy service it was known as the Chesapeake. One Vindicator, an extended range variant called the SB2U-1, was modified with a pair of Edo floats to become the XSB2U-3. Here we see it being tested in US Marines livery, pushed by a couple of Marines/sailors standing between the floats. Photo: U.S. National Museum of Naval Aviation

The XSB2U-3 Vindicator in flight with US Navy markings. The aircraft proved a poor performer and was taken out of service, and returned to SB2U-1 standard. Photo: US Navy via WarbirdInformationExchange.org

The lumbering tri-motor Junkers Ju.52 utility transport was used in all fronts and in all situations—on wheels, skis and floats. As Germany began to lose air superiority later on the war, the Tante Ju (Auntie Ju) became a sitting duck for Allied fighters. Any Ju.52 on floats would not have had a chance without fighter escort. Photo via Pinterest

A Royal Air Force Northrop Nomad on floats in 1943. The squadron code GS on the side indicates that the Nomad is from 330 Norwegian Squadron. 330 Squadron was formed in Iceland in 1941. It was manned by escaped Norwegian pilots and aircrew who were trained in Canada. The Nomad N-3PB was built on floats to a Norwegian specification and used by them for anti-submarine patrol, torpedo bombing and coastal work. Photo: Flying Officer Woodbine, RAF via Imperial War Museum

A Ryan PT-22A Recruit trainer on floats. Recruit seaplanes were ordered by the Netherlands Air Force... to be powered by a 160 Menasco engine. The order was cancelled and then 25 were built for the United States Army Air Corps. Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum

A Ryan Recruit flies over the Pacific off the coast of California, wearing the markings of the Netherlands Air Force. Note the difference in the engines between this shot and the previous—this one a Menasco in-line and the previous shot a Kinner radial. Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum

The Bristol Bolingbroke was a Canadian variant of the Bristol Blenheim light bomber and patrol aircraft. They were built by Fairchild Aircraft Ltd in Longueuil, Québec. Only a single Mk III was constructed (RCAF serial number 717). It was taken on strength by the Test and Development Establishment at RCAF Station Rockcliffe in Ottawa. It was immediately modified to a float plane and made its first flight just a month later from the Ottawa River. The scene depicted above looks to be the float plane base at Rockcliffe, with the paper mills at Gatineau belching in the distance. A ventral fin was added for stability after initial test flights, making this photo likely around the time of those first flights. Also, the aircraft and Edo floats look brand new. Photo: RCAF via WW2Talk.com

In November of 1940, on floats, RCAF Bolingbroke 717 flew to Dartmouth, Nova Scotia to join 5 Squadron (Bombing and Reconnaissance) for further tests on salt water until February 1941. There are several websites that claim these shots were taken at No. 5 (BR) Squadron in Dartmouth. But 717 was on floats with that squadron from 5 November until February. If this was Dartmouth, it would be likely be snowy, and it would definitely not have trees in full leaf. This is most definitely Rockcliffe. Photo: RCAF via WarThunder.com

The Canadian-built Bristol Bolingbroke was a good looking airplane on wheels, and on floats it looked even better. Photos: RCAF via IPMSCanada.com

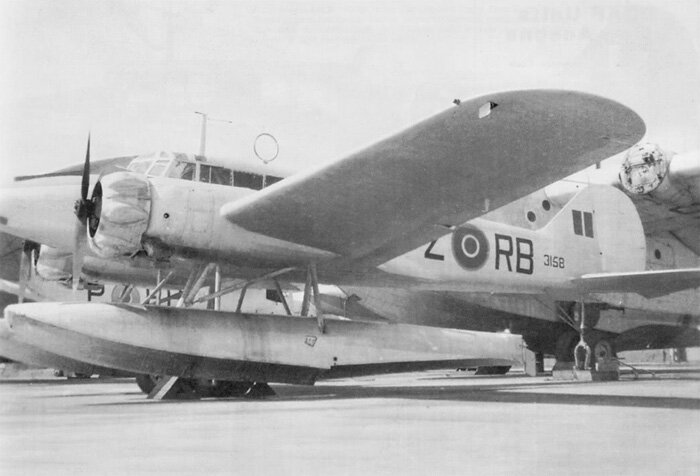

One Avro Anson (Serial 3168-2RB) was converted in 1946–47 by the South African Air Force to a float configuration to help new 35 Squadron crews convert to the challenges of water operations. The Anson would help the rookie flying boat pilots adjust to taxiing on water before they graduated to the much more challenging Short Sunderland flying boat (one is just visible behind and to the right of the Anson in this shot). 35 Squadron operated from Air Force Station Congella at the Maydon Wharf in Durban. Photo via AirfixTributeForum

The singular Avro Anson (former RAF N4927) equipped with floats is seen in Durban, South Africa’s harbour. We can see here the bow-hatch in the nose of the Anson, used for mooring. The gun turret was removed from the aft fuselage and as a result this particular Anson was not flyable and was simply used to teach pilots and crew seamanship and moving about on the water. Photo via saairforce.co.za

The Douglas DC-3/C-47, often considered the most important aircraft of all time and in particular of the Second World War, was critical in delivering supplies and personnel on all fronts in every theatre. As the US Navy, Marines and Army began to have success island hopping on their way to Japan, it was thought a heavy amphibious transport would be needed, and the Gooney Bird got the call. Edo, the number one float designers and suppliers in America, designed for the C-47C a pair of one ton floats, the largest they had yet built. Each float was 42 feet in length! To put that in perspective, a P-51 Mustang was only 32 feet long. Photo: rccanada.ca

The Douglas C-47C float plane was a handful to fly—difficult to get off of and land on water. It handled poorly in a crosswind and, as one would imagine, sluggish compared to the wheeled variant. Photo via 1000AircraftPhotos.com

A Canadian Army L-19 Bird Dog (16715) from the Light Aircraft School at Rivers Camp Manitoba sets up for a landing on a nearby lake (Lake Wahtopanah) during Army pilot training circa 1956. Photo via John Dicker

In a very artistic image, another Canadian Army Bird Dog (16710) taxis in to shore after a successful landing on Lake Wahtopanah. Photo via John Dicker

A one-off North American Rockwell OV-10 Bronco on floats. The light attack and Forward Air Control (FAC) platform was a versatile twin turboprop light armed reconnaissance aircraft of Vietnam War vintage. It is not known how far the float-equipped Bronco got in testing. Photo via AFWing.com

Combat Ski-Planes

In Canada, we have a saying… There are two seasons—winter and 6 months of poor snowmobiling. One would think that, with her massive land form blanketed in snow for a good portion of the year, Canada would be a country that fully embraced ski-plane technology for its combat aircraft—like Finland. Truth be told, the Royal Canadian Air Force was, during the Second World War, and indeed even today, an operator of ski-equipped aircraft. During the war however, this was largely to permit training to continue apace in regions of heavy snow and for liaison aircraft flying in and out of these bases. There were many military aircraft to be found on skis in Canada, but they were elementary training aircraft, bush planes like the Noorduyn Norseman during the war, the de Havilland Canada Beaver and Otter in the immediate postwar period and the Twin Otter today.

There was no pressing need in Canada to provide ski-equipped combat aircraft... the war—the one on snow—was conducted very far away. The Finns, Swedes and Soviets, however, were conducting combat operations in geography and weather conditions that necessitated squadron strength ski-equipped fighters and dive bombers. Unlike float experiments with fighters and bombers, ski-adapted combat aircraft were, for the most part, relatively successful—particularly in combat zones where the enemy was also on skis.

There were, however, experiments with ski-equipment for RCAF fighters like the Hurricane and Canada was a testing ground for some American experiments with equipping fighters with skis. This photo compendium addresses simply those aircraft you would not expect to be on skis.

We’ll start the combat ski-plane section off with the rarest of all fighter aircraft to be found on skis—the Supermarine Spitfire. In truth, the only Spitfire known to have been fitted with skis was Spitfire Mk XIV (TZ138), having been selected for winterization trials and shipped to Canada in late 1945. It was then shipped by rail to Edmonton and assembled there. After initial trials, it was sent to Fort Churchill on the coast of Hudson Bay for some deep cold tests. The 1,000+ mile flight from Edmonton required a fuel stop in Le Pas, Manitoba. On the return from Fort Churchill, the Spitfire swung on landing at Le Pas and struck a snow bank, seriously damaging the propeller. After a new propeller was installed, attempts to get the Spitfire off the snowy field (there was no snow clearing equipment) failed and rather than damage another propeller, the pilot (Mike Hayward of the Royal Canadian Navy) returned to the hangar. An excerpt from Spitfire Survivors Then and Now, Vol. II by Gordon Riley, Peter Arnold and Graham Trant explains what happens next:

“Hayward noticed that the only other aircraft in the hangar was a de Havilland Tiger Moth on skis. Eyeing the skis, he set a plan in motion. It would have been beyond the limit of their rudimentary tools to install the skis on the Spitfire’s landing gear but they could build a wooden box structure on each ski and then place the aircraft’s wheels into the boxes. In theory they would fall away from the aircraft following take-off. At the risk of breaking another propeller, Hayward carried out a taxi test with the skis in place on 27 February 1947. Since there were no brakes, the aircraft moved forward even with the throttle at idle. The taxi test was exciting as the Spit slithered around on the snow but the idea seemed to work.

By noon the next day, work was completed and the weather forecast was very good. Since the runway was completely covered by snow, Hayward and his crew had to guess and positioned the aircraft accordingly. Advancing the throttle, the Spitfire began to move smoothly but, just before flying speed, it hit a bump and one wheel came out of its box. The starboard ski did a backward somersault over the tail section, just as Hayward and his crew had feared, it made lots of noise but resulted only in some gouges in the aluminium skin. As TZ138 took off the other ski fell free as planned, Hayward flew for 2.5 hours before landing uneventfully at Namao. He later recalled that no one seemed thankful that the aircraft arrived at its destination nor was the RCAF even remotely interested in the temporary ski modification. He did, however, feel that all credit should go to the Royal Canadian Navy!” Photos: Peter Arnold Collection

Hawker Audax on skis, RCAF (Serial No. K3100) during winter trials at RCAF Station Rockcliffe, Ontario, 17 Mar 1935. The aircraft is fitted with an R.A.E. heating bag with R.R. primus heater. (Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3580835)

The Wikipedia pages for the Hawker Hurricane and its variants make little mention of the two Canadian Hawker Hurricanes equipped with skis. The first was a former Mk I from the Royal Air Force (AG310) which was temporarily converted with Noorduyn skis at Canada Car and Foundry in Fort William (Thunder Bay). Later, it was modified to Mk XII standard and taken on strength by the RCAF as 1362. The second (above), was a Mk XII modified with skis. It was lost, likely crashed in a lake near RCAF Bagotville, Québec. Canadian aviation historian Lee Walsh has been working for a number of years to track down witnesses and photographic evidence that will lead him to find the RCAF’s only ski-equipped Hurricane. Photo: RCAF

Hurricane 1362 being converted to ski gear at Canada Car and Foundry in Fort William (Thunder Bay).

Hurricane XII, RCAF serial 5624 (above), was tested on skis in February and March of 1943 at RCAF Station Rockcliffe’s Test and Development Establishment. The following month, whilst flying with Number One (Fighter) Operational Training Unit at RCAF Bagotville, it went missing. Photo: RCAF

North American NA-61 Harvard 1321 was one of the first batches of American-built Harvard trainers to be delivered to the Royal Canadian Air Force, being ferried to RCAF Station Sea Island, British Columbia in July of 1939, two months before the declaration of war with the Germans. A few weeks later, en route to Trenton, Ontario over the Great Lakes, 1321 suffered some minor damage at North Bay on Lake Nipissing. For the next year, it bounced around Ontario flying schools including Trenton, Borden and then Ottawa (Uplands). In the winter of 1940–41, it was sent to Noorduyn for the installation of skis (the cost of the ski modification was quoted in R.R. Walker’s excellent RCAF Serials resource site as $3,263.34 ). From Noorduyn in Montréal, it returned to RCAF Station Rockcliffe in Ottawa for testing of the ski equipment as well as other winterized kit (extended exhaust and heater). These tests were conducted by Rockcliffe’s Test and Development Flight until the middle of March 1941. While many of the elementary trainers such as the Tiger Moth, Finch and Cornell did in fact operate on skis, the more powerful Harvard was perhaps too much of a handful on skis and none were put into service at advanced flying schools. Photo: RCAF

A scan of a rare colour transparency of a Fairchild Cornell in skis at No. 13 Elementary Flying Training School at St. Eugène with Vintage News subscriber Peter Jenner standing in the late afternoon sun. Ski-equipped training aircraft seem to have been the norm at St. Eugène as Bob Kirkpatrick trained on ski-equipped Fleet Finches during his days at No. 13 EFTS. For young men from Great Britain like Jenner and for Americans like Kirkpatrick, taking off and landing on skis would be a novelty worthy of a photo or two for the folks back home. Photo via Peter Jenner

An RCAF de Havilland Tiger Moth gave little protection against winter—a weak cabin heater and only the thickness of fabric and Perspex to fend off -30C temperatures. Local Eastern Townships resident Yvon Goudreau was a civilian member of the Ground Crew at No. 4 EFTS Windsor Mills. Here he poses next to a winterized Tiger Moth (canopy and skis) on a lovely winter’s day. Photo: Johnny Colton Collection

From snooping around the Internet, it seems that only two countries experimented with Lysanders on skis—the Finns and the Canadians. Here a National Steel Car-built RCAF Lysander sits not on a snowy runway, but the frozen surface of a lake or river. Since Lysander with RCAF serial 459 was used to test skis at Rockcliffe’s Test and Development flight, this is quite possibly the Ottawa River. The tests were also conducted at a place called Porquis Junction, Ontario, north of Timmins and close to the Iroquois Falls airport. Clearly it was there to do winter testing. One thing of note is the skis added to the Lysander’s already formidable vertical height and the angle of its stance. The Finnish example later in this story had skis that did not seem to add to the height. Photo: RCAF

Avro Anson (RCAF serial No. 6195—Ex RAF W1631) sits on skis during tests with the RCAF’s Test and Development Flight at Rockcliffe in the winter of 1941–42. The ski equipment looks jury-rigged—a wooden platform that accepts the extended wheels of the Anson. Photo: RCAF

In the early months of 1944, a P-51A-1-NA (Serial number 43-6003) was fitted and tested with lightweight and retractable ski landing gear at Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. The design was in response to the thought that maybe, as forces were pushing the Germans back across Europe in the months ahead, the Allies would need fighters that could operate from unprepared fields in winter conditions. When the gear was retracted, the skis were housed in a compartment formed when the P-51A’s centreline Browning machine guns were removed from the fuselage. The aircraft proved to perform quite well, with take-off distances around 1,000 feet. The gear package added 390 lbs to the overall weight and increased hydraulic pressure was required to retract the skis. The development of the long-legged P-51D eliminated the need for fighters to operate from forward areas in the winter. Photo: Wikipedia

It seems that pretty well every fighter aircraft was given a chance on skis. With the war likely to run through the winter of 1944–45 and the lend lease program in full swing with the Soviets, even the massive P-47 Thunderbolt had a ski tryout. From what I can tell, this P-47C Thunderbolt is sitting exactly in the same spot as the P-51 Mustang in the previous photo—which I believe to be Winnipeg, Manitoba. Photo: P47.KitMaker.net

United States Army Air Force P-47C (Serial No. 42-24964) warms up on a Winnipeg airfield. Results were far from satisfactory, with the aircraft’s rudder unable to counteract torque on skis. It was put back on wheels and flown back to the US. Photo: forum.kepypublishing.com/Hank Dallinger Collection

Captain Randy Acord was the Project Officer and pilot of a P-38 Lightning cold weather experiment in Alaska in the winter of 1943–44. The Lightning was equipped with temperature sensors throughout that helped the USAAC and Lockheed to understand the temperatures reached for machine gun lubrication, engine lubrication, cabin heat, carburetor heat, fuel distribution problems etc. Photo and information via akpub.com

Captain Randy Acord taxies his one-of-a-kind Lightning on snow in Alaska in 1943. Of the ski tests with the P-38, Acord had this to say: “The conditions were ideal for our tests, and I made 165 landings, with complete retraction and extension of the skis between each landing. The interest around the base was high, especially among the Russians based at Ladd Field. Every operation was successful, even the dive test, during which the plane reached speeds up to 450 mph. The advantages were small, though. The ski loading was 640 pounds per square foot, and regardless of the depth of the snow, the skis went to the bottom of it. The propeller clearance was only 14 inches and we could plow that much snow on wheels. The skis worked well on rough snow, covered ground, or ice with cracks, while on glazed ice the landing slide was 7,000 feet. With no torque involved and the engines idling at 500 rpm, it was easy to do figure eights on the ground in the width of the runway.” Photo and information via akpub.com

According to Captain Randy Acord’s account every operation was successful. This image of the ski-equipped Lightning belly down on Fairbanks, Alaska’s landing Field seems to indicate that at least one flight was not so successful. Photo: USAF via wwdb.com

A P-63A Kingcobra (Serial Number 42-68887) taxies into a bit of trouble during trials. According to Wikipedia, it was the Soviets who conducted ski tests with the P-63, but this is clearly an American Kingcobra. Photo: USAF

Accident records on the Aviation Safety Network indicate that the single Curtiss P-40N Warhawk (42-106129) on skis was written off on 16 August 1944 in an accident on Andrews Lagoon, Adak Island in the Alaskan Aleutians. There is no telling whether this was a frozen lagoon and the aircraft was on skis, but by August, the Aleutians are free of ice as far as I know. The aircraft was flown by John Norman of the 11th Fighter Squadron of the 343 Fighter Group. Photo via shu-aero.com

At least two Kingcobras were fitted with skis as evidenced by Bell P-63 Kingcobra (42-68931) sitting on skis in a particularly unsuitable taxiing environment—at Wright Field in October 1945. Photo: USAF via Wikipedia

A Kawasaki Ki-61 Tony fighter on ski-equipped landing gear operating from Hokkaido in 1943. Photo via WarRelics.eu

A Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa (Oscar as it was known by the Allies) on skis with a rare four-bladed propeller—testing for cold weather operations. The tests were conducted in anticipation of conflict with the Soviets in the Kuril Islands. Photo via allaircraftsimulatins.com

Mitsubishi Ki-51 “Sonia” dive bomber being tested on skis at Obihiru Airfield, Hokkaido, Japan. The aircraft was painted white, though it is not evident on this image.

When the German army got bogged down in the brutal winter of 1941–42, following Operation BARBAROSSA, the Luftwaffe, flying combat support, found new challenges such as operating aircraft from constantly changing airfields in the worst winter in decades. Here mechanics show Luftwaffe officers a Junkers Ju-87B.2 Stuka being tested for ski operation on 22 December. Photo: Bundesarchiv.de

Another Junkers Ju-87 set for winter operations. The skis look different on this D-model (Dora) Stuka (DJ+FU) than the previous photo, so likely several test aircraft were involved. It is not known if the ski-equipped Stuka was ever used operationally, but given the lack of photographic evidence on the web, it is unlikely. Photo: Asisbiz.com

A Messerschmitt Bf-109 had many different variants. One was the Bf-109W, a variant on floats of which there is little photographic record and this unknown variant on skis. Very little is to be found about this aircraft, so anyone with better photos or info is encouraged to email us. Photo via ww2aircraft.net

It was very difficult to get information on either the Bf-109 on skis or this Focke Wulf Fw.190 on skis. Doing a rather basic translation from a Slovakian Wikipedia page, it seems that in the winter of 1941–42, one Fw.190.A.2 (RI+KW) was fitted with non-retractable wooden skis, with tests conducted at Gardermoen air base, near Oslo, Norway (today’s Oslo Airport). Due to a significant decrease in performance, the ski-equipped Würger (Shrike) was abandoned. Photo via PakistanAffairs.pk

A Heinkel He-111 medium bomber is tested on retractable skis or “Schneekufen” at Gardermoen near Oslo. Note the wooden slatted structure upon which the skis sit in this photo and the previous one. Early on, it was found that as the aircraft were taxiing, the bottom of the ski would warm up from the friction of the snow. On shut-down, the skis would immediately freeze to the snow. When it came time to move off, it was quite a project to get the aircraft free of the formed ice. The answer was that the taxied aircraft were parked on a pad of some sort to prevent the freeze-up. In Canada, most bush pilots know of the problem (they learn quick, some of them), and resort to cutting fir tree branches and parking their aircraft on top. Photo: Asisbiz.com

An Avia Bk.534 of the Slovakian Air Force warms up on a cold day at the Trencianske Biskupice airfield. The Avia was designed and built in Czechoslovakia in the interwar period, but in March of 1939, Nazi Germany forced the partition of the country and took over the Czech component while installing the Slovak half as the Slovak Republic. The Slovenské vzdušné zbrane (Slovak Air Force) was constituted from units of the Czechoslovak air force that were based in Slovakia. The new force was gifted about 70 B.534s and Bk.534s. Photo via Vrtulnik.cz

Flygvapnet – The Swedish Air Force

Like the Finns, the Swedes are a resourceful and determined people—not to be trifled with. Though they were neutral during the Second World War, they still had an air force and they were under no misconception about their national safety. Long before the war, the Swedes had developed experience with combat aircraft on skis... out of necessity. Skis enabled them to operate anywhere during winter and to disperse their aircraft to keep them from being destroyed in airfield strikes. When the Finns found themselves in the Winter War with the much larger Soviet Union, Sweden sent a ski-equipped combat unit called F-19 to support the Finns in operations in the far north. With Swedish national markings painted over with the blue swastika (which had nothing to do with the Nazi symbol), the Swedes fought side by side with their fellow Scandinavians against the Slavic Soviets. The Soviets had triple the manpower, 100 times more tanks, and 30 times more aircraft... but they were unable to really get the upper hand in a substantial way. In the end, the Finns were forced to make concessions, but the Soviet Red Army was humiliated by their inability to crush a much smaller opponent. In addition, the League of Nations was seen to be absolutely powerless to do anything about the Soviet invasion of Finland, which they considered illegal. The Soviet Union was tossed from the League, but this did nothing to stop the Soviet advance on Finland.

Perhaps one of the most important outcomes of the Winter War was the pathetic performance of the Red Army. In the Red Army’s humiliation, Adolph Hitler found encouragement to move forward with a plan to attack the Soviet Union. Just a few days after the commencement of Operation BARBAROSSA, the German invasion of the USSR, the Soviets and Finns went at it again in what became known as the Continuation War.

Sweden, though a neutral country, was also preparing for the eventuality of a winter war. Here, a BT-17 variant of the Northrop A-17 Nomad dive bomber sports what appear to be retractable skis as well as rocket rails. Photo via WorldofWarplanes.com

Pegasus-powered Hawker Harts of the Swedish Air Force warm their engines in squadron strength—in both wheeled and ski configurations. Photo via AviaDejaVu.ru

There may be no colder place on the planet than 1,000 feet above the sub-Arctic forest of Sweden, sitting in Hawker Hart M in a 150 mph wind and no ability to move. The Swedes were a tough bunch though! Many of the Swedish Air Force aircraft used the same ski equipment as the Finns. The Hawker Hart M was a Pegasus-powered variant, with the engine and aircraft licence-built in Sweden. This aircraft was with Flygflottillj 19 (F-19), a volunteer unit that operated in northern Finland (Lapland) in the second half of the Winter War. In this photo, the aircraft and pilots have just returned from Finland and have painted over the Finnish markings they flew with in the combat theatre. Photo: WarThunder.com

A Swedish F-19 mechanic readies a Hawker Hart as it waits patiently in the cold of a Lapland winter for night to fall (which, in the arctic winter, is most of the day). The Swedes have taken many winter precautions—skis, custom wing tarps to keep ice from forming, and covers for the cockpits and engine. At the Swedish Air Force Museum at Malmslätt, there is a Hawker Hart and Gloster Gladiator in the markings of F-19 during the Winter War. Photo: ww2aircraft.com

Two shots of a Finnish-marked Swedish Gloster Gladiator in camouflage and ski gear in January 1940 during the Winter War. The photo at bottom shows ground crews standing by as F-19’s Wing Commander Kapten Ake Söderberg warms his engine prior to a mission. While the ski gear likely degraded the performance of the Finnish/Swedish Gladiator, they were fighting against Soviet aircraft on skis with similarly affected speeds. Photo: Hakans Aviation

Northrop designed the B-5 (A and B) dive bomber specifically for the Swedish Air Force (Flygvapnet). Based largely on the Nomad, they were built in Sweden and were powered by a Swedish-built version of the Bristol Mercury radial engine. Here we see a “Flottiljer” (flotilla) of Northrop B.5Bs on skis during an exercise in the winter of 1941. Photo via WorldofWarPlanes.com

The Swedish Air Force operated almost 100 of the Northrop B-5A and B-5C. Given that it was likely winter when this photograph of B-5A “29” was taken, it seems that it was a miserable job being the rear gunner. The comfort of the gunner seems to have been completely ignored as there is not even a wind screen to divert the air flow for this poor bugger. Photo via RCGroups.com

This photo of a Swedish Northrop B-5A is testament to the fact that ski-equipped aircraft operations are difficult on everyone—even the ground crews. Photo via ww2photo.se

Ilmavoimat – The Finnish Air Force

It makes sense that the land of the greatest ever ski jumpers, biathletes and cross-country skiers would also have the widest experience in operating ski-equipped military aircraft. Tiny Finland, faced with fighting a voracious Soviet Red Army, became a co-belligerent state with the Axis powers. While they did not sign the Tripartite Pact with Germany, Italy and Japan, they were aligned with Germany against the Soviet Union later in the war. At the beginning, in the Winter War of 1939–40, they were left to fend for themselves against the Soviets. The Winter War resulted in concessions to the USSR (the Karelian Isthmus and other areas). When the Germans invaded the USSR in Operation BARBAROSSA, Finland allowed German aircraft to refuel at Finnish bases. In retaliation the Soviet Union bombed bases across Finland and the Finns in turn declared war on the USSR. The Finnish Air Force would operate a complex array of borrowed, bought and recovered aircraft from American, British, Czechoslovakian, Dutch, French, German, Italian, Soviet, and Swedish manufacturers. Many of these types were modified to operate on skis.

While Canadians were experimenting in 1943 with ski-equipped Hurricanes for defensive and operational training squadrons, all they had to do was consult the Finns who had played with the idea two years previously (on Hurricane HC454) during the “Continuation War” against the Soviets. They went as far as making the skis retractable, but the system was not practicable and the concept was dropped. Photo via warthunder.com

The Finnish Air Force (Ilmavoimat) was perhaps the most experienced operator of ski-equipped combat aircraft in the world leading up to and through the Second World War. The tiny yet persistent and courageous air force operated aircraft designed in Holland, Great Britain, the United States and Germany. At the outbreak of the war with the Soviet Union on 30 November 1939, the primary fighter aircraft of the Ilmavoimat was the Fokker D.XXI, an inexpensive fixed gear fighter. Operating their aircraft on skis allowed the Finns to disperse them around the countryside rather than concentrate them at airfields which were easily bombed by the Soviets. The 50 D.XXIs built by the Finnish State Aircraft Factory (in Finnish, an unpronounceable Valtion Lentokonetehdas) were powered by a Swedish-built Pratt and Whitney Twin Wasp engine. The little fighter produced its share of aces, with Jorma Sarvanto being its highest scorer with 12.5 victories. Given the clarity of this photo and the identical-to-the-last-detail museum example below, it is possible that this black and white shot in snow is in fact the museum’s restoration in a staged photo. Not sure. Photo via Pinterest

The Finnish Air Force Museum (Keski-Suomen Ilmailumuseo) has a beautifully restored Fokker D.XXI (FR-110) on skis. While not familiar with the type, I find it a handsome aircraft. It would be a marvelous thing to see one of these old warbirds fly from snow once again. Photo: Jukka Kolpannen, Wikipedia

In a more peaceful time, Finnish Bristol Bulldog Mk IV on skis visit an airfield at Sortavala, a town near the Russian border in 1936. The town of Sortavala was in an area ceded to Russia after the Winter War. The Finnish Karelians evacuated the town and today it lies in Russia on the northern shore of Lake Lagoda, populated by Slavic Russians. Photo via slon-76:livejournal.com

Much maligned by American and British pilots, the Brewster Buffalo was, in the hands of the determined Finnish, an effective fighter. The Wikipedia page dedicated to the Buffalo explains it best: Several nations, including Finland, Belgium, Britain and the Netherlands, ordered the Buffalo. Of all the users, the Finns were the most successful with their Buffalos (known simply as the Brewster or Taivaan helmi (“Sky Pearl”) or Pohjoisten taivaiden helmi (“Pearl of the Northern Skies”)), flying them in combat against early Soviet fighters with excellent results. During the Continuation War of 1941–1944, the B-239s (a de-navalized F2A-1) operated by the Finnish Air Force proved capable of engaging and destroying most types of Soviet fighter aircraft operating against Finland at that time and achieving in the first phase of that conflict 32 Soviet aircraft shot down for every B-239 lost and producing 36 Buffalo “aces”. Photo via WW2Aircraft.net

A Finnish Lysander on skis taxies as a snow covered airfield. The Finnish Ilmavoimat had 4 Mk Is and 9 Mk IIIs. They were used during the Winter and Continuation Wars against Russia and then against their former ally Nazi Germany. They were mostly used in an observation or reconnaissance role but also for dropping light bombs as evidenced by the bomb racks on the stubs protruding from the wheel pants. Photo via ww2Photo.se

The ski pants on this two-seat Fokker C.X dive bomber (FK-81) give it a comical look, as if from some Pixar animated film. FK-81 was stationed at Lappeenranta in December of 1939. The Dutch-designed Fokker was licence-built by the Finns up until 1942, with 35 Bristol Pegasus-powered examples being built. The Finnish C.Xs served with distinction in the Winter War, the Continuation War and the Lapland War. The last of the seven Finnish C.Xs that survived the war crashed in 1958. Photo via Go2War2.nl

Another Fokker C.X dive bomber on the Finnish/Soviet front shows that the Finns were used to winter operations. The engine shroud appears to have a connector at the bottom for heated air to warm its Bristol Pegasus engine. It also has a cover for the cockpit canopy to prevent icing. As well, this Fokker (FK-100) has the addition of a tail-ski. Photo via WW2Aircraft.net

Three Avro Anson I aircraft (RAF serial Nos. K8738, K8739, and K8740) were purchased by the Finnish Air Force in 1936 for bomber crew training. In this photo we see Anson AN-102 on skis in the winter of 1937–38. The aircraft was painted overall dark green with sky grey undersides and bare metal cowlings. AN-102 crashed in 1943. Photo via GoPixPic.com

At the beginning of the Winter War in November 1939, the tiny Finnish Air Force was equipped with only 17 bombers and 31 fighters. The most modern aircraft in the Finnish arsenal were the British-designed Bristol Blenheim bombers that had been licence-built in Finland. Some of these, such as BL-106 (above), were equipped with skis covered in special fairings which prevented snow and ice from building up on the ski equipment. It is clear that these were never meant to retract. Photo via mybb.ru

Another Bristol Blenheim with what appears to be retractable ski undercarriage. Photo via theMiniaturesPage.com

A Gloster Gauntlet of the Finnish Air Force basks in the short-lived winter sun at Vesivehmaa in the winter of 1941–42. Photo via slon-76.livejournal.com

Finnish Gloster Gladiators are readied for a mission on a frozen lake near the Finnish–Soviet front during the Winter War.

A Finnish Gloster Gladiator in the Finnish Air Force Museum in the same camouflage and ski gear as the previous photo. 22 Gladiator pilots claimed a total of 45 kills with the type, but after the Winter War, it was mostly outclassed by modern Soviet and German aircraft. It lingered on in service until 1945, but in recce and liaison duties mostly. Photo: Wikipedia

Soviet Air Defence Forces

Our image of Russia in the Second World War is one of hoards of cheering Red Army soldiers charging across a frozen plain in white winter gear, followed by T-34 tanks splashed in white paint and covered in more soldiers. It’s an image of a great nation fighting for its very life with their one great weapon—sheer numbers. The Russians understood winter in a way the Germans never would. They embraced the harsh environment with simple technologies and uncomplicated weapons systems—tanks and aircraft that were easy to fix and operate especially on snow and ice at unprepared and constantly moving air fields. Ski technology was an important part of their winter wars.

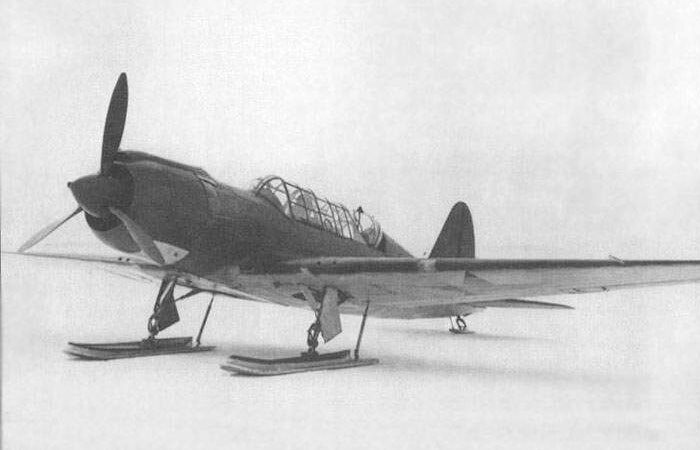

The first aircraft designed by Pavel Sukhoi was the Su-2 light bomber. It performed well enough in the Winter and Continuation Wars, but was obsolete by the time of the Great Patriotic War. Su-2 No. 15116 is photographed with ski landing gear, during trials in the Research institute of Air Force in March 1942. Photo: Sukhoi.org

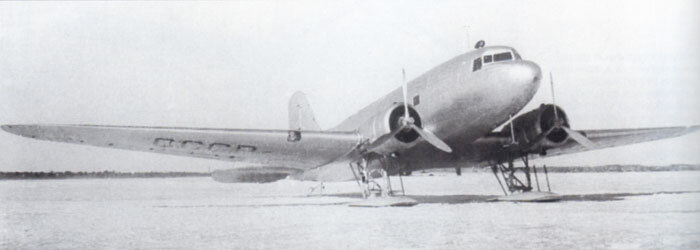

The Lisunov Li.2 was originally a licence-built Soviet version of the DC-3. Built in fairly large numbers (6,157), it was modified for ski operations in Arctic regions.

An entire squadron of Lavochkin Gorbunov Gudkov LaGG-3 fighters are lined up with propellers in sync for a parade on the Eastern Front in the winter of 1942–43. While Canada is equally blanketed in snow during the winter, there was little incentive to get fully operational on skis. Only the Soviets, Swedes and the Finns really put skis and combat aircraft together in an organized and successful manner. Perhaps if the front was in Canada, there would have been more pressing impetus to deploy aircraft on skis at the squadron level. Photo: SovietWarplanes.com

A close-up of a ski-equipped LaGG-3 with sophisticated retractable ski undercarriage. Photo via AviaDejaVu.com

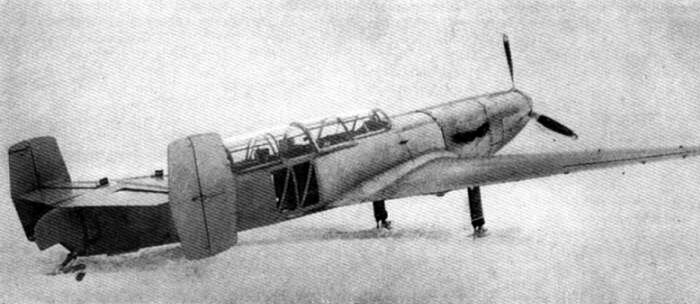

A Yakovlev Yak-7V on the Eastern front in the winter of 1943–44—looking pretty comfortable on skis on a bright snowy day. The Yak-7 was a development of the Yak-1. It was originally meant to be a fighter-trainer, but then was redesigned as a fighter, and finally, reverted to its original role as a training aircraft. The two-seat trainer was designated Yak-7V, with 510 being built as such and 87 converted from a fighter variant. Both the Yak-7V and the two-seat Kay-7UTI (and earlier communications and training variant) were equipped with skis. Photo via SovietWarPlanes.com

The Ilyushin Il-2 Shturmovik was a heavily armoured Soviet ground attack aircraft of the Second World War, and at more than 36,000 copies built, the most manufactured aircraft in aviation history. Here an early variant undergoes non-retractable ski testing in January 1942. Later examples had retractable ski gear. Photo via Mig3.SovietWarPlanes.com

Another Ilyushin Il-2 Shturmovik shows us the difference with retractable ski equipment, retracting into an enlarged gear fairing. Photo via Mig3.SovietWarPlanes.com

Another Ilyushin Il-2 Shturmovik shows us the difference with retractable ski equipment, retracting into an enlarged gear fairing. Photo via Mig3.SovietWarPlanes.com

This view of the Yak-1 demonstrates the wide and stable stance of the aircraft on skis... slightly lower than the wheel configuration. The skis, similar to those used on the LaGG-3 and the MiG-3, had a bottom surface that was only good for about 70–80 take-off and landing cycles. Some Yaks used “take-off” skis which were simply sliding platforms with a ramp like rear. The Yak-1 pilot would roll forward on wheels, up the ramps and into the skis. The skis were then left behind as the aircraft took off. Photo via Ram-Home.com

A Kamov-Skrzhinsky A-7 Autogiro, designed by Nikolaï Kamov, was the only armed autogiro in history to see combat action—in the Winter War with Finland. In this photo we can see a defensive machine gun in the rear cockpit and hard points for bombs under the wings. One assumes that the gun had detents that prevented it from shooting off its own rotor. Designed in 1934, it was used primarily for observation and artillery spotting. Photo: Bellabs.ru

A Tupolev SB (also called the ANT-40) thunders across an icy airfield (or perhaps a lake), lifting its tail-ski off the ice as it gathers speed. It was used during the Winter War against the Finns. At this time, virtually every bomber (94%) in the Soviet air force was a Tupolev SB. Photo via asisbiz.com

A Tupolev SB 2M-100A fitted with non-retracting skis during the Winter War against Finland in 1939. The suffix SB stood for Skorostnoi Bombardirovschik—“high speed bomber”. SBs, fitted with skis for operation from snow covered airfields, were slower and more vulnerable, while the need to wear heavy winter clothing made the gunner’s job even harder. By the end of the 15-week war, at least 100 SBs had been lost, with the Finns claiming nearly 200 shot down. Photo via Mig3.SovietWarPlanes.com

Here, in a highly staged propaganda photograph, no less than 12 airmen prepare a Tupolev SB twin-engine bomber for a mission on non-retractable skis. Photo via Mig3.SovietWarPlanes.com

File this under You Learn Something New Every Day. Prior to compiling this photographic study, I had never heard of nor laid eyes on the Bolkhovitinov S “Sparka”. The Sparka was powered by two Klimov M-103 engines positioned in tandem in the aircraft’s nose, each powering one half of a counter-rotating twin propeller. The version shown here was a single engine variant (S-1), which was tested on skis in early 1942 but was considered underpowered with a single Klimov M-105P, attaining a top speed of 249 mph (400 km/h). Regardless, she was a hot looking machine. Photo: Bernhard C.F. Klein Collection via 1000AircraftPhotos.com

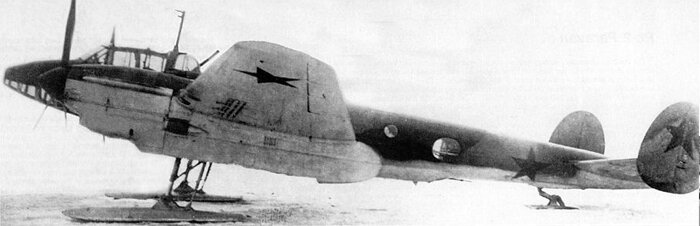

The Petlyakov Pe-2 Peshka (Pawn) was a Soviet dive bomber introduced in 1941 and still in service in 1952. It was very successful as a ground attack aircraft, a night fighter, reconnaissance platform and heavy day fighter. The designers at Petlyakov worked on perfecting a retractable ski gear that would not affect its performance, but the system degraded it speed considerably and the ski-equipped Pe-2 was cancelled. Photo via ww2aircraft.net

The retractable ski equipment for the Petlyakov Pe-2 Pawn utilized the same struts and oleos as the wheeled version. Photo via ww2aircraft.net

A Polikarpov I-16 fighter, the bantam cock of Soviet fighter aircraft, carries tail code “White 11” and the banner “Freedom of the Oppressed”. This aircraft was flown by Major George Petrovich Gubanov, Hero of the Soviet Union and the Commander of the 13th Squadron of the 61st Brigade of the Red Banner Baltic Fleet Air Force. The Polikarpov I-16 was, at its introduction in 1934, a revolutionary design being the world’s first low-wing cantilever monoplane fighter with retractable landing gear to have attained operational status. Photo: Bellabs.ru

This I-16 Ishak (Donkey) Type 10 was a ski-equipped variant. One wonders if the Soviet pilots of the late 1930s were true Communist Party members, writing jingoistic slogans like “For the Constitution of the USSR!” on the sides of their ski-plane fighter aircraft. Were these banners heartfelt or did the unit’s political commissar force the ground crews to paint the slogans on the side for propaganda photos in newspapers. Anywhere else, young testosterone-fired fighter pilots would have painted a scantily clothed pin-up girl and named their aircraft Hot Mamma or Sack Time. Photo: Bellabs.ru

This I-16 Ishak (Donkey) Type 10 was a ski-equipped variant. One wonders if the Soviet pilots of the late 1930s were true Communist Party members, writing jingoistic slogans like “For the Constitution of the USSR!” on the sides of their ski-plane fighter aircraft. Were these banners heartfelt or did the unit’s political commissar force the ground crews to paint the slogans on the side for propaganda photos in newspapers. Anywhere else, young testosterone-fired fighter pilots would have painted a scantily clothed pin-up girl and named their aircraft Hot Mamma or Sack Time. Photo: Bellabs.ru

The Polikarpov I-180 during tests in the Winter War of 1939–1940. The I-180 was the ultimate development of the smaller I-16. The early testing and failure of the type proved fatal to test pilots and to the career of Nikolaï Polikarpov. Photo via ww2aircraft.net

Post Second World War

A Lockheed P2V-2N Neptune “Polar Bear” touches down on an Antarctic ice field. Two United States Navy Neptunes were modified as Polar Bears (strange choice of a name as they were designed for Antarctic service, where there were no polar bears) as part of Project Ski Jump. Their weapons were removed and they received skis and Jet Assisted Take Off (JATO) rockets. The skis were 16 feet long and could be retracted into fairings under the engines. Photo: US Navy

With JATO bottles on her sides and belly blasting 30 seconds of rocket assistance, a Polar Bear Neptune takes off from Antarctica. Photo: US Navy

A Canadian Forces Cessna L-19 Bird Dog (16703), ski-equipped, in flight near Petawawa, Ontario circa 1968. 703 would have been on strength the Artillery Air Observation (Air OP) Troop based at Petawawa. 703 would be lost to a fatal accident on 13 July 1989, while with the Air Cadet League of Canada, towing gliders at Princeton, BC. Photo: DND

Perhaps one of the best known and most successful military aircraft on skis is the Lockheed LC-130 Hercules of the United States Navy. These heavy lifters of the Navy’s VX-6 squadron first landed at the South Pole in 1960–61. The aircrfat pictured above (JD321) was the first to accomplish the feat. The US Navy continued the Polar service until the late 1990s when the task was transferred to the New York Air National Guard.

A Lockheed C-130 Hercules of the New York Air National Guard’s 109th Airlift Wing. The 109th Airlift Wing’s mission is to provide airlift support to the National Science Foundation’s South Pole research program by flying specialized LC-130H Hercules airlifters, modified with wheel-ski gear, in support of Arctic and Antarctic operations. The 109th Airlift Wing is now the only unit in the world to fly these aircraft, but it was the Navy that did the pioneering. Photo: Wikipedia

We end on perhaps the most unlikely ski-equipped aircraft, the Sukhoi S-26. The grammatically incorrect sign in front of this Monino Museum exhibit explains: “Two prototypes were successfully tested under development and state tests in 1963–1966. The aircraft provided capability of being operated on soft airfields with low density ground (down to 4–5kg/cm2). The aircraft had been approved for putting into volume production which, however, has not been commenced. Experience gained from the tests was used to develop the Su-7BKL aircraft with wheel-ski landing gear and the Su-17 aircraft had provisions for ski installation.” Photo: Wikipedia

The Sukhoi S-26 ski/skid test bed aircraft led to the development of the Su-7BKL Fitter with a unique ski-wheel landing gear that enabled it to operate from wet and rough field conditions. Photo: Wikipedia