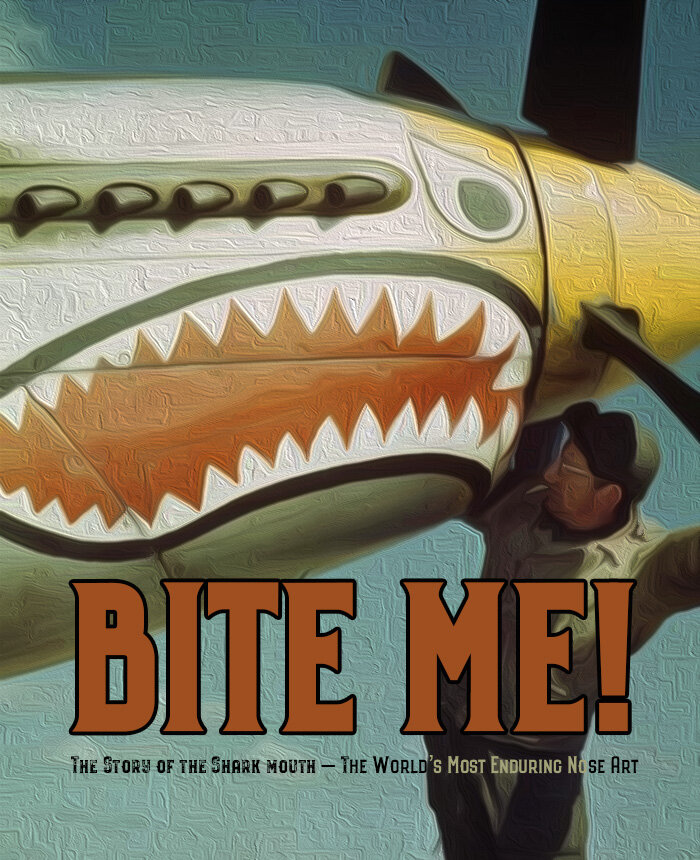

BITE ME! The Story of the Shark Mouth, the World’s Most Enduring Nose Art

In the beginning—the very beginning—aircraft designed and built by early aviators like the Wrights, Curtiss or Blériot had more in common with dragonflies or even scaffolding than eagles or sharks. These contraptions of bamboo poles, corded lashings, canvas panels, taut wires, brass fittings, thrashing propellers and wooden frameworks were fragile, open structured things that nonetheless captured the imaginations of men and women around the globe. Blunt, exposed and draggy, they had none of the predatory visual attributes that would one day come to define military and even civilian aircraft. Newspapers of the day called these first aviators “birdmen” and made natural and poetic connections to the flight of birds, but in truth, these flimsy craft were but lumbering, staggering jalopies, more turkey than turkey vulture. But this would very soon change.

As time progressed and aircraft designs improved, their forms began to comply with aerodynamic laws as builders sought to compensate for the cumulative drag created by wires, braces, struts, flat radiators and exposed pilots. For streamlining purposes and the comfort of crews, accommodations for pilots and observers began to be somewhat enclosed, while the structural complexities of fuselages and empennages became covered with fabric to aid in the uninterrupted flow of air over structural and control components. Aircraft began to look less like Meccano constructions or scaffolding and more like birds or even fish—two animal forms that lived and moved within a fluid world. In an attempt to emulate the successes of birds and fish within their realms, designers began to deliberately take design cues from these animals. These design developments began to shape aircraft in a very specific way, one that would lead pilots and crews to see their aircraft as predatory birds or fish.

While there may have been earlier instances of applying paint or markings to an aircraft in order to imply a connection between craft and creature, the earliest photographic instance I can find on the internet was a fragile but beautiful Donnet-Lévêque flying boat known as the Flygfisken (Flying Fish), made in France and operated by a Swedish flying instructor by the name of Carl Cederström. Many believe that the earliest applications of faces, and in particular fish or shark faces on aircraft were to fighters, bombers and recce aircraft of the First World War. The Flygfisken, however, clearly dates to 1913, and the idea itself possibly to 1912 when the aircraft was ordered from the factory—about ten years after the first powered flight by the Wright Brothers. It is likely that there are earlier and similar ideas, but for the purposes of this photo essay, that is where we will start.

Perhaps the earliest photograph of an aircraft with a fish motif, if not a shark, is this early Swedish-operated flying boat nicknamed Flygfisken or Flying Fish. The type was a 1913 French-built Donnet-Lévêque flying boat, painted overall in fish scales and an interesting piece of typography which acts as the mouth. The photo was taken at Lake Roxen in southeastern Sweden where it was operated at the Carl Cederström flight school, based in Linköping. Cederström was a Swedish aviation pioneer, trained at the Blériot flying school and the first to hold a Swedish pilot’s certification. The aircraft was a two-seater with an 80 hp Gnome rotary pusher engine. Not long after this photo was taken, the aircraft was sold to the Swedish Navy and was designated L II. It was retired in 1918 with just 130 hours on the airframe. It is now on display (without the early Flygfisken paint scheme) at the Swedish Air Force Museum in Malmslätt, Sweden. Photo: DigitaltMuseum.se

There are many instances of the application of a snarling skull, shark, fish or animal mouth on aircraft of the First World War, but it seems that it was up to the discretion of individual pilots and observers. It was in these early years that it became evident that painting your airplane in such a manner gained the public’s interest when photographed and printed in newspapers. People loved the sense of humour, the aggressive attitude and in the case of skull heads, the nightmarish vision.

In combing the internet for historical and contemporary applications of the shark mouth motif, it became clear that there are literally thousands upon thousands of instances of its use—individual aircraft, entire squadrons, civilian as well as military, gliders as well as powered aircraft and nearly every common type of aircraft has had, at one time or another, a snarling shark mouth applied to its nose. There is no way that this story could ever begin to include all of these aircraft from history. Instead, I have collected a small sampling of about 90 images that take us from the earliest examples of the idiom, through its military heyday in the Second World War to the aircraft of today. It was difficult to know where to stop and what to include, but this selection will, if anything, demonstrate its astounding ubiquity. The shark mouth appeared in every air force on the planet, on any type of aircraft and at any historical period since the beginnings of flight.

Today, the shark mouth motif is used well outside of aviation, gracing automobiles, ships, motorcycles, guns and the arms of the odd debutante with attitude issues. It continues to be used by fighter and bomber units from Japan to Turkey to Russia and is the go-to graphic device to activate any aircraft’s qualities of pugnacity, aggression, or anger. Today, this would be called a “meme” — an element of a culture or system of behavior that may be considered to be passed from one individual to another by non-genetic means, especially imitation. Long before the memes we see today (the Keep Calm and Carry On meme comes to mind), the shark mouth has remained relevant for more than 100 years, an outstanding achievement for a simple graphic device. There is no doubt that, centuries from now, space ships will continue to employ the shark mouth for its universally understood meaning and for its timeless appeal.

Dave O’Malley

We could not possibly showcase even a small fraction of the instances of its use, but if you have a special image you would like to see added to this repository, send it along with a written caption of no less than 20 words, and we will add it to the project. Here now is a tribute the greatest nose art of all time—the shark mouth.

Related Stories

Click on image

THE FIRST WORLD WAR

A Maurice Farman MF.11 (nicknamed the Shorthorn by crews) was far from being piscine in its visual personality, but the gondola, which included two eye-like round glazed portholes in front for the gunner/observer inspired this crew to add a grimacing mouth. The aircraft was designed before the First World War and was used as a light bomber/recce aircraft early in the war. Not a shark mouth per se, but a photo of one of the earlier uses of a mouth motif. Photo: modellismopiu.it

Two of the three-man crew of an A.E.G G.IV show off their shark mouth bomber in 1918. The A.E.G. G.IV, built by the easy-to-say Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft, was a biplane bomber introduced in late 1916 by the German Air Force. It had a relatively short range and was used primarily as a tactical bomber. There is only one example of this aircraft still in existence today—right here in Ottawa at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum (CASM)! This CASM aircraft is also the only surviving example in the world of a twin-engine German aircraft from the First World War. Photo via wingsnutwings.com

A real painting challenge for the scale modeller would be this American Nieuport 24 from the First World War, painted from nose to tail as a fish. Since sharks don’t actually have scales, one cannot say for certain whether it was meant to represent a shark or perhaps another predatory fish. It has a fairly nasty looking bite with teeth around the engine cowling, though the Nieuport 24 was not much better than the Nieuport 17 which it was designed to replace. Most were soon relegated to advanced training units like this example at an American training field in France. Photo: LargeScalePlanes.com

It is appropriate that one of the earliest applications of a shark mouth on a military aircraft was on this L.F.G. Roland C.II as the type’s nickname was Walfisch (Whale). Built by Luft Fahrzeug Gezellschaft, the Roland C.II type entered service in 1916 as a general reconnaissance platform. This particular Roland C.II was flown by Leutnant Richard Seibert and his observer/gunner Hauptmann Pfleger of the Bavarian Feldfliegerabteilung 5 on the Western Front in the autumn of 1916. Seibert who, along with Pfleger, is likely one of the men in this photograph, was killed a few months later. Note the homey curtains in the windows of the fuselage (reputedly painted on). Photo via pinterest.com

Another Roland C.II, this time painted in all-white snow camouflage for winter operations and flown by ace Eduard Ritter von Schleich (likely the man in the photo) with Bavarian Feldfliegerabteilung 2b during the winter of 1915–1916. In addition to the mopey-looking whale mouth, von Schleich also had a carved whale or fish attached to his external air speed indicator (above fuselage). The name Roland, of course, is a reference to the mythic Teutonic knight of German legend. Photo: modelersalliance.com

Two Belgian airmen—Lieutenant Jules Jaumotte (L) and his observer/gunner Second Lieutenant Louis Wouters lean against the lower wing of their French-built Farman F.40 with an effigy of a death’s head on the nose of its crew nacelle. Many early examples of this type of nose art involved grinning skulls and strange faces, all with a gaping and terrifying mouth. The duo of Jaumotte and Wouters were the most successful Belgian aerial photography crew of the First World War, widely recognized as the best in their craft. Though Wouters started off his flying career as an observer, he gained his pilot wings and returned to the front as a fighter pilot with No. 11 Squadron. Perhaps the addition of the grotesque leering skull saved them from being shot down, as the Farman F.40 was far from a fighting ship. Photo: modellismopiu.it

THE SECOND WORLD WAR

There were many instances of Luftwaffe aircraft of the Second World War sporting shark mouth nose art. In fact, the Germans were likely the first to use the graphic device in the war. This Messerschmitt Bf 110 E fighter is one of the best known cases in point—the yellow noses and shark mouth of the famed “Haifischgruppe (Shark Group)” — II.Gruppe/Zerstörergeschwader 76 in the Greece and Balkans campaign. Though effective, it seems an upward turn of the mouth would give it a much more aggressive visual effect. As such, it looks more like a lamprey than a shark. Photo via britmodeller.com

Aircraft like the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk and Hawker Typhoon, with their open mouths to accommodate air flow over radiators and oil coolers, were the perfect aircraft for the shark mouth treatment. This early model Messerschmitt Bf 109 C (with a two-bladed propeller) of the Luftwaffe getting its machine guns re-armed is a case in point. The dark hole only intensifies the concept. Photo via forums.ubi.com

Desert Sharks of the Royal Air Force’s North African war plough through the dust and heat—the first Allied aircraft to wear the shark mouth and the inspiration for Claire Chennault and the American Volunteer Group later in China. 112 Squadron appears to be the very first to employ the classic shark mouth that we all know and use today. At bottom, a 112 Squadron Kittyhawk Mk III taxies in the dust and scrub at an airfield near Medenine, Tunisia in 1943. 112 Squadron, Royal Air Force, was reputedly the first Allied unit to employ the shark mouth motif—appearing on their Kittyhawks in the summer of 1941. A ground crewman directs the pilot down the narrow taxi path from a perch on the port wing. Photos: RAF

Three Kittyhawks of 112 Squadron Royal Air Force warm their engines before a mission in the North African desert. 112 Squadron’s depiction of the shark mouth has become the iconic form that we all know and love today. Even the Flying Tigers copied them when they saw a story about them in London Illustrated News. Photo: RAF

One of the early Curtiss Tomahawks of 112 Squadron Royal Air Force demonstrates the manner in which the open jaw of the shark almost obscures the large chin intake. Photo: WarThunder.com

This photograph, though very poor, illustrates the way in which the rendering of a shark mouth and eyes can change the character of the aircraft. In this 112 Squadron Royal Air Force Mustang, the slant of the teeth, the aggressive forward placement and downward slant of the eyes and the sneering curl of the mouth all combine to make this Mustang far more aggressive looking than the slightly goofy looking Mustang in the following photo. Photo via raf-112-squadron.org

112 Squadron, the first to employ the “classic” shark mouth that remains today an icon, flew into the jet age and never gave up their shark mouth. In June 1944, 112 Squadron gave up their P-40 Kittyhawks and took delivery of N.A. P-51s (known as Mustang IV in RAF service) for the battle through Italy, keeping these till disbandment in 1946. During the war the squadron aces included Battle of Britain Ace, Billy Drake, and Neville Duke, later to be a test pilot and world speed record holder. The squadron reformed at Fassberg as part of RAF Germany in May 1951 with de Havilland Vampire FB5s, and decorated them with their famous “Sharkmouth” insignia. The insignia continued on their F-86 Sabres in 1955. After re-equipping with Hunters in 1956, the squadron was disbanded at the end of May 1957. Photos and info: Ken Cothliffe

A Hawker Hunter, the last of the 112 Squadron Sharks, ending a 112 shark reign of more than 15 years. Photo: aviadejavu.ru

The Mustang remains one of the most beautiful and iconic aircraft of the Second World War and one of the most celebrated canvasses for nose art. This P-51B Virginia (sn 42-106486) of the 382nd Fighter Squadron is likely named for its pilot’s girlfriend or maybe his birthplace, but the real showstopper is this happy, googly-eyed shark mouthed face. The shape of the Mustang’s nose, like the P-40, offers a natural face to dress in the shark motif. In behind Virginia is parked another 382nd shark mouth called Big Mac. Photo via jonbius.com

While several Royal Air Force and Luftwaffe units had been using the shark mouth motif earlier in the Second World War, it was the 1st American Volunteer Group (AVG) of the Chinese Air Force that became the best known for the style, at least in America. Known as the Flying Tigers, the unit nonetheless utilized an obvious shark mouth on the noses of all their P-40 aircraft. Here P-40s of the 3rd Squadron Hell’s Angels line up in echelon right on a sixth P-40 flown by legendary AVG pilot Robert Tharp Smith. There is no doubt that the shark mouth applied to the shark-like lines and gaping maw of a P-40 Warhawk/Tomahawk/Kittyhawk represents the quintessential application of the motif, one that has inspired cartoonists, tattooists, and artists for more than 75 years. Photo Robert “Tadpole” Smith

Not all the Curtiss P-40s that fought in China were AVG Flying Tigers, but many emulated the shark’s mouth motif in homage. Here seven pilots of the 75th Fighter Squadron of the 23rd Fighter Group pose with P-40K King Boogie at an airfield in China in 1943. In fact, a number of AVG pilots did join the 75th Fighter Squadron (nicknamed the Tiger Sharks) when America declared war on Japan. King Boogie was assigned to Captain William D. “Beel” Grosvenor, credited with 5 victories over Japanese aircraft. The unit is still active today, flying A-10A Warthogs… with shark mouths of course!! Photo: WorldWarPhotos.info

No two shark mouths were the same on aircraft of the Second World War as shown by these two 23rd Fighter Group Warhawks parked on a Chinese airfield—different teeth, eyes and shapes. The Nipponese Nemesis was reportedly flown by Captain Matt Gordon of Pueblo, Colorado. Photo: LIFE

Five shark-mouthed Curtiss P-40 Warhawks line up on the 16th Fighter Squadron’s flight line in China in October of 1942 while a group of Chinese mechanics work on attaching a new centreline external fuel tank. Looking closely at the painting of the shark mouth on Rose Marie, it shows a certain disdain for neatness. The 16th was part of the 23rd Fighter Group in China, the unit that took over the role of the American Volunteer Group when it was disbanded. They also took the Flying Tigers name and some of its pilots. Photo: WarbirdInformationExchange.org

Pilots of three shark-mouthed A-10A Thunderbolt II Warthogs of the modern 23rd Fighter Group prepare for a training mission. The group can trace it lineage back to the Flying Tigers and P-40 operations in China and retains that name and symbol to this very day. Photo: Wikipedia

This bombed-up and shark mouth A-10A of the modern 23rd Fighter Group appears a bit cross-eyed as she looks up at the advancing refuelling probe from a 927 Air Refuelling Wing KC-135 Stratotanker. Photo: gizmodo.com.au

Despite the fact that the Germans and the British were using the shark mouth device earlier in the war, it was the American Volunteer Group’s P-40s that first aroused America’s devotion to the shark mouth. The name Flying Tigers and the Hell’s Angels (one of the AVG squadrons) also helped to promote the AVG to heroic status before they had even met the Japanese. Images from the web

The radial engine fighter had considerable challenges to overcome to be taken for a shark. With a blunt nose and wide open engine air intake, it’s not what one could say was as sleek as a shark, but when the United States Navy’s VF-27 Fighter Squadron, the Fighting Hellcats, painted their Grumman F6F Hellcats, they put in some compensating attitude with their depiction of a snarling cat from hell. A website dedicated to VF-27 states: “Pilots Carl Brown, Richard Stambrook, and Robert Burnell, designed the cat-mouth markings during VF-27’s training at Kahului Naval Air Station, Maui, Hawaii, in March and April 1944. Each of the squadron’s pilots helped with the painting, but Burnell, the artist of the squadron, did most of the work. All 24 of VF-27’s F6F Hellcats were so marked when the squadron embarked aboard the light carrier USS Princeton on May 29, 1944. Nine VF-27 Hellcats were airborne when the Princeton was hit, all nine landed safely on other carriers in the Task Force. Other commanders were not amused by the funny markings on VF-27’s Hellcats. The “Cat’s Mouth” markings were promptly painted out as per USN regulations. So ended a legend in U.S. Naval Aviation.” Photo: lostworldsinc.com

The most effective nose for a shark mouth was that of a fighter aircraft with an in-line and perhaps a chin air intake, but nearly every aircraft type of the Second World War sported the device at some time and compensated in other ways. Clockwise from top left: A— The Republic P-47D Thunderbolt The Bug (serial number 42-76653) of Captain Arlie Blood of the 510th Fighter Squadron, 405th Fighter Group, 9th Air Force in the summer of 1944. This aircraft is the subject of a Revell 1/48 scale model kit. B—A combat-weary Focke-Wulf Fw 190 A formerly of Jagdgeschwader 26 was given a half comical/half ferocious paint scheme when it was used as a training aircraft by JG 1 in France in the spring of 1942. C—One of the more famous of the wildly painted assembly ships of the Eighth Air Force, Spotted Ass Ape of the 458th Bomb Group combined the gaping maw of a shark with multicoloured polka dots over three quarters of her fuselage and wings. Alternately, it was known as Wonder Bread for its similarity to the packaging for the famous-but-tasteless bread. D—There is some dispute as to whether we can call all these gaping mouths “shark mouths”, especially if they are used on say P-40s of the Flying Tigers or this Boeing B-17 Tiger Girl (42-3555) from the 560th Bomb Squadron of the 388th Bomb Group, USAAF. Surely it must be a tiger mouth and not a shark mouth. Whatever, it certainly spits fire! Tiger Girl was lost on a mission to Bremen on 26 November 1943. Photos: ww2incolor.com, forum.largescaleplanes.com, 458bg.com, and pinterest.com

One of the most beloved Spitfire paint schemes of the Second World War was that of 457 Grey Nurse Squadron of the Royal Australian Air Force in the South East Asia Command (SEAC). The Aussie squadron was formed in Great Britain in 1941, as were many RCAF squadrons of the new 400-series. After a deployment to the Isle of Man and then RAF Redhill, 457 was moved home for the defense of Australia near Darwin, Northern Territory, eventually fighting the Japanese from airfields in Morotai and Labuan, Dutch East Indies. The shark mouth began to appear on some squadron aircraft (at first smaller and lower on the nose) and then eventually large, gaping, snarling and on every squadron aircraft. The name Grey Nurse started appearing also aft of the engine, a reference to the grey nurse shark that inhabits Australian waters. Photo: Australian War Memorial via Wikipedia

An interesting shark mouth Hawker Hurricane Mk IIb with Vokes filter shows us how good the Hurri looked with a quasi-happy shark face. The Hurricane carries its RAF serial (BP654) on the tail in the style of the United States Army Air Force. This is because it is an American unit hack, having been “acquired” by the 350th Fighter Group in Sardinia and modified to two-seat tanden configuration. It was lost over the sea on August 6, 1943 after the pilot bailed out safekly following engine failure. Photo: AmericanAirMuseum.com

Combine the sleek lines of the Martin B-26 Marauder medium bomber and a shark mouth and the effect is very aggressive looking. This particular Marauder is USAAC serial number 42-107582 and flew with the 454th Bomb Squadron of the 323rdBomb Group. The unpainted Marauders were not as heavy as the camouflaged versions and as such were slightly faster. The pilot standing in front is possibly the ship’s commander Captain McAndrew. Photo: Bundesarchiv

The nose of the North American B-25H was a fearsome thing as it was—with four 50 cal. machine guns and four additional 50 cals. on the fuselage sides—but the grimacing and clamped-down shark mouth of one called Mortimer added another dimension of fear. Many of 90 Attack Squadron’s heavily-armed Mitchells and Douglas A-20 Havocs sported variations of the shark mouth while fighting in the South Pacific. The shipping-busting Mitchells earned the nickname “commerce destroyers”. During the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, every one of 90 Squadron’s commerce destroyers scored a hit on a convoy of 18 Japanese ships. 90 Squadron exists today with the USAF, flying the Lockheed F-22A Raptor. The name Mortimer is a possible reference to Mortimer Snerd, the contemporary ventriloquist dummy of Edgar Bergen. Photo via 90thattacksquadron.yolasite.com

Martin Marauder 42-96165 of the 599th Bombardment Squadron of the 397th Bombardment Group had a full set of markings worthy of note (in the bottom photo only). First, she wears the yellow and black fin flash of the 397th Bombardment Group and D-Day stripes on her wings and aft fuselage. She also wears a spectacular shark mouth motif, but it’s difficult to tell if this was meant to be a shark, since the aircraft’s nickname was The Big Hairy Bird and close examination reveals that the artwork includes a pair of horns aft of the cockpit windows (see colour image). Photos: Imperial War Museum

A sexy Italian car. This 71st Fighter Squadron crew chief is having a little fun using a drop tank from a Lockheed P-38 Lightning in Lesina, Italy. It looks like it sits on the chassis and wheels from a bomb cart and there is no indication that this car is a working automobile, but it looks cool with its shark mouth scheme. In the background is a 71st FS P-38L Lightning (sn 44-25734) called Betts II. Photo: worldwarphotos.info

Like father, like son. While the gaping shark mouth came from the fact that fighter aircraft reminded pilots of predatory fish, not all shark mouths were in fact sharks. Some were dragons, crocodiles, bears, skulls and in the case of this Alaskan campaign Warhawk, a tiger. This bright yellow design of a tiger on the nose of an 11th Fighter Squadron remains today a favourite of modellers and artists for its graphic and abstract qualities. The 11th FS was part of the 343rd Fighter Group, who called themselves the AleutianTigers. The unit was commanded by none other than John S. Chennault (pictured here in cockpit), the son of General Claire Chennault, the legendary commander of the American Volunteer Group. Nearly all of the unit’s Warhawks were painted this way. John S. Chennault was Lt. General Chennault’s son from his first marriage and one of 11 siblings. At the time that he commanded the Aleutian Tigers, he was a lieutenant colonel. He went on to fight in Korea and retired as a full colonel. He died in 1977 and is buried beside his father in Arlington National Cemetery. Photo: Wikipedia

The 15,000th P-40 to come off the Curtiss assembly line in Buffalo, New York was painted with the roundels of every air force that was then operating or had operated the type, as well as a shark mouth and Japanese and German kill markings. There is a Hasegawa plastic model kit of this very aircraft with all the requisite roundels. Photo: Central Repository for Aviation Photos on Flickr

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator was less a shark and more of a whale in terms of performance, but it was a favourite aircraft canvas for the shark mouth motif. Hundreds of the boxy bombers were painted with a gaping mouth in every theatre of war. Here, B-24D Liberator Moby Dick (41-24047) of the 320th Bombardment Squadron of the 90th Bombardment Group poses with her little sister, a Piper L-4 Grasshopper Moby Dick Jr. Many of the 320th Jolly Rogers Liberators were painted with a shark/whale mouth device. During the Second World War, the squadron was based in Northern Queensland, Australia and supported campaigns in New Guinea, Borneo, and Formosa before repositioning to Okinawa. Today, the 320th is one of the USAF’s top missile squadrons. Photo: Nebraska State Historical Society

As threatening as the crew of this Italy-based 15th Air Force B-24 Liberator hoped their artwork would be, it doesn’t seem to frighten this diminutive squadron cur. Photo via Pinterest

The Swiss may have been neutral, but they weren’t about to look like a bunch of sissies either. Here a Swiss Air Force Messerschmitt Bf 109 (J-713) sports a gaping red-lipped shark mouth. The strategic placement of the shark’s eye on the fairing for the machine gun ammo feed adds to the bold effect. Photo: aviacaoemfloripa.blogspot.com

A pair of Swiss Air Force Messerschmitt Bf 109 Emils of the 21st Fliegerkompanie lurks happily in the long grass at a Swiss airfield near Olten. The eyes of these sharks give them a sort of manic look of surprise. Photo: Pinterest.com

While the Fairey Battle had a very martial name, it had a distinctly miserable martial career. Powered by the same engine as the Spitfire, it weighed nearly 1,500 pounds more and suffered in performance accordingly. Meant to be a light bomber/heavy fighter, it was immediately outclassed and utterly devastated by Luftwaffe fighters in the Battle of France. It was quickly pulled from front line duty and shipped to Canada where the type served as a gunnery platform with all eleven British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) Bombing and Gunnery Schools from Ontario to Alberta. Most of the Battles, like this example, were painted yellow overall as were most BCATP aircraft. Perhaps to give students and bored staff pilots a sense that they were part of the fighting war and to instill an aggressive spirit, several were painted with bold shark mouth designs. Photo via network54.com

Another shark mouth Fairey Battle (RCAF serial 1679, ex RAF L5477) of No. 9 Bombing and Gunnery School, Mont-Joli, Québec, offers a voracious image of a shark leaping to the attack. Too bad the Battle had none of the aggressive performance suggested by this nose art. Photo: whatifmodellers.com

North American B-25 Mitchells, with their massive frontal fire power, were popular canvasses for gaping jaws of all kinds, from dragons and tigers to birds of prey to angry sharks such as this B-25D Runt’s Roost. Runt’s Roost (sn 41-29727) was part of the 90th Bombardment Squadron of the 3rd Bombardment Group and the assigned aircraft for Lieutenant Joseph “Runt” Helbert. The Mitchell was modified in the South Pacific theatre with an extra 20 mm cannon in the nose along with the usual eight 50 cal. machine guns for offense and defence. Photo via Pinterest

For an airplane that was affectionately known as “Dumbo” or the “Gooney Bird” because of its fat and soft lines, this Second World War C-47 looks particularly menacing. Photo via Internet

There are not many photographed examples of shark mouth Soviet aircraft of the Second World War, but the device was certainly popular. Here a Yakovlev Yak-9 (possibly flown by famed ace Abrek Arkadevich Barsht or Mikhail Semyonovich Mazan) lies partially hidden in a tree line hiding from predatory German fighters. Photo: sovietwarplanes.com

The bright red Tupolev PS-9 (ANT-9) Krokodil was a Soviet passenger aircraft of the 1930s. It came in two- and three-engine variants. The twin-engine variant had a rather normal looking nose, except for one particular aircraft that was heavily modified into a propaganda ship named after a Soviet satirical magazine called Krokodil. They added a long reptilian proboscis and painted underbitten crocodile teeth on its nose, claws on the wheel pants and even the addition of triangular crocodile plates on the fuselage top. Very strange indeed. The Cyrillic text on the fuselage side says “Krokodil”. Photo via rcgroups.com (top), dishmodels.ru (bottom)

The Soviets played around with shark mouth motifs as well, but many seemed to be crocodile mouths such as on this crudely painted Petlyakov Pe-2 bomber and recce aircraft. The bulging eye just below the cockpit truly finishes the crocodilian effect. Photo Bichura.ru

While many “nose artists” were highly skilled and some superbly exuberant in their expression of the shark mouth idiom, some, like the man who painted the mouth on this snaggle-tooth Douglas A-20 Havoc of the 47th Bombardment Group, though lacking in ability, were still able to give their mounts an aggressive persona—the shark equivalent of a junkyard dog. Photo via aviacaemflorips.blogspot.com

It’s not known whether this B-17G (42-32012) known as Shark Tooth got its name from its nose art or the other way around. This snarling nose makes maximum use of the twin 50 cal-spitting guns in its chin turret to deliver a lead message. The aircraft was a veteran of 64 bombing missions (mostly to German targets) and was the favoured ride of the Herbert W. James crew who flew her 14 times in the latter part of her career. Photo: 401bg.org

Perhaps the most terrifying and angriest of the shark mouth aircraft of the Second World War was the raging open maw of this Hawker Typhoon (MR-U, RAF serial MP197) of 245 Squadron of the RAF’s 2nd Tactical Air Force. The effect gives one the feeling that one is about to be swallowed. 245 Squadron “Tyffies” sported bright blue noses as well—to have all that colour and snarl at the mouth of an already gaping hole makes this aircraft the author’s favourite shark mouth of all time. Canadian decal manufacturer Aviaeology makes a complete set of decals for this aircraft. Photo: IPMSUSA.org

A Focke-Wulf Fw 190 F8 Mica of the Hungarian Air Force does not have a shark mouth on the aircraft itself, but rather the centreline fuel tank and the underwing bombs which have detonation probes to ensure they explode above ground. Photo via Marek Lakatos

A squadron mechanic with artistic ability sketches the outline form of a mouth on this USAAF North American P-51 Apache in the China Burma India theatre of the Second World War. Photo via gndn.wordpress.com

This may be a photograph of the same Apache aircraft from the previous photo, but after the application of its shark mouth and eyes. Photo via gndn.wordpress.com

The shark mouth motif was particularly popular in the China Burma India (CBI) theatre of operations during the Second World War, likely because of the early success and fame of the American Volunteer Group in China. This P-51B Mustang Jeanne III (41-37058) of the 51st Fighter Group is shown in a rare colour period photo somewhere in theatre. The text in the white square painted aft of the cockpit says rather strangely “Los Angeles City Limits”. This aircraft is the same aircraft that is depicted in the next photograph. Photo via sovietwarplanes.com

While the North American P-51D Mustang is universally considered the finest model of the type, the turtleback B-Model exudes a toughness and, with the addition of a snarling shark mouth, a nastiness and readiness to get dirty. This P-51D flew with the 26th Fighter Squadron of the 51st Fighter Group. The squadrons of the 51st Fighter Group flew from bases in Karachi, India and Burma, flying Curtiss P-40s. In 1945, the squadron re-equipped with Mustangs to defend the eastern terminus of the Burma Hump and bases in the Kunming, China area. Photo via WorldWarPhotos.info

While “shark-mouthing” a P-38 Lightning made for a school of attacking predators, it made for twice the work for squadron artists. This Lightning was operated by the 35th Fighter Group which had many shark-mouthed “Twin-Tailed Devils”. Photo via WarbirdInformationExchange.org

When you have four Rolls-Royce Merlins with their open mouths screaming for shark mouth motifs, why just do the fuselage? Here a Canadian-built Avro Lancaster (KB772, VR-R) known as Ropey, sits on the ramp at a Canadian base after the war where it was stored briefly before operating with the RCAF’s Maritime Command. The name Ropey was added to the fuselage prior to its return to Canada, but KB772 flew at least 33 ops in the five months it was with 419 Moose Squadron. The Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum in Hamilton, Ontario painted its Lanc’s engines in Ropey’s markings for a brief time. Photo: RCAF

In this author’s humble opinion, the de Havilland Mosquito was one of, if not the best looking aircraft to come out of the Second World War. While a shark mouth made it look more badass, it takes away from the fine and beautiful lines of this French Armée de l’Air Mosquito (“avec une gueule de requin”, as the French say) from the Indochinese War of the mid-1950s. Like putting an angry face on a Jaguar E-type, it was just not necessary. This Mossie FB.4 (RF873) was operated by the French G.C. “Corse” for just a few months after they formed up on Morocco and were sent to Indochina (Vietnam). The wood construction and cellulose glues of the plywood bomber fared very poorly in the extremely humid and tropical climate of Vietnam and the type was soon withdrawn from service. Photo via RCGroups.com

When one thinks of the shark mouth vernacular, fire breathing fighters and attack bombers come to mind immediately, but even fat, unarmed combat gliders can have their shark personas, such as this German Gotha Go 242. Perhaps it gave a degree of confidence and a sense of control to the defenceless pilot as he looked for a safe landing spot on the Eastern Front. Photo via Pinterest

Not a shark mouth... but a sentiment much appreciated by this author. A P-51D (This appears to be a different Mustang than the original one names Bite Me! 44-13334 G4-U) of the 362nd Fighter Squadron, 357th Fighter Group, USAAF, flown by Captain Alva C. Murphy of Knoxville, Tennessee (not sure if this is Murphy in this shot). This is the same fighter group that Chuck Yeager flew with in his Galmorous Glenn Mustangs. Photo: Manthos.net

THE COLD WAR

Immediately following the war, the first generation of jet fighters continued the shark mouth tradition, likely with veteran Second World War pilots at the controls. Here, a Lockheed F-94B Starfire of the 61st Fighter-Interceptor Squadron, USAF (a development of the T-33 Shooting Star (Silver Star in Canada)) sports a massive red shark mouth with a somewhat bemused eye. Just below the cockpit windscreen is a single white star and a name. At first I thought that this indicated that it was the personal aircraft of a one-star general, but the device (a red background) appears on other squadron Starfires as does the same red shark mouth. It is not known where this photograph was taken (though likely Selfridge Air Force Base in Michigan), but for a long time (1953 to 1957), the squadron was based in Newfoundland at Ernest Harmon Air Force Base. They operated Starfires at Harmon for at least one year. Photo: media.defense.gov

Two French F-100 Super Sabres sporting beautiful shark mouth gashes under their chins. The snout intake of the F-100 “Hun” was problematic for a shark mouth design, but by placing the mouth farther back on the nose and putting the angry eye forward of the mouth, the effect is excellent with the shark-like shape of the fuselage. All 11 “Huns” of 04/011 Jura (Squadron), which operated from a French base in Djibouti, were eventually painted with this same device. One of my favourite of all the shark mouths for its simplicity. Photo: Yves Le Milbeau via SuperSabre.com

The shark mouth concept was not just limited to fixed wing aircraft. Here a UH-1 Iroquois, or Huey as they were universally known in Vietnam, sports a massive shark mouth—the unit identifier of the famed 174th Assault Helicopter Company. Photo: cs.finescale.com

This shark mouth Mil Mi-24 Hind looks more insectoid than shark-like and the mouth gives it the look of a joker-esque and voracious praying mantis. Photo via wallpapereswa.com

While the Israelis may know a thing or two about aggressive fighter tactics, they might not be the best at the shark mouth motif. The nose of this French-built Dassault MD-450 Ouragan (French for “Hurricane”) fighter of the 113 Tayeset “Ha’ Tsira’a” (Lions Head Squadron), looks not only ill-proportioned, but more like a tear in the metal than a gaping mouth. The colour image shows a similar aircraft preserved at the Israeli Air Force Museum at Hatzerim. During the Six Day War, 113 Squadron lost eight of its 24 Ouragans. Photos: Top: acig.info, Bottom: Wikipedia

It is possible that these Grumman F-11 Tigers of VF-21 Mach Busters are not depicting sharks, but as the aircraft name suggests, Tigers—with black noses and orange yellow eyes and mouth. Regardless of the animal or creature they represent (tiger, crocodile, dragon, etc.) these all derive from the original shark mouth concept. Photo: Pinterest.com

The US Navy’s fighter squadron VF-21 Mach Busters (previous photo) would become, in 1959, a fleet replacement attack squadron called VA-43 and known as the Challengers. Though the name, number and mission would change, they kept the same shark mouth motif for their Douglas A-4D Skyhawks. Here we see a Challenger Skyhawk trapping aboard USS Antietam in 1959. Photo: Pinterest.com

The F-4 Phantom II was one of the meanest and most pugnacious-looking aircraft in the world in its heyday, but by adding a cannon spitting shark mouth, the attitude level of this Turkish Air Force Rhino is right off the charts. With its sloping nose, cranked wings and downward slanting stabilators, some wags say that it’s as if they got the Phantom halfway out of the design hangar when the door slammed shut on it. Photo: Horatiu Goanta

Captain Dan Cave, the Deputy Commander Carrier Air Group, USS George Washington, launches in his F/A-18E Super Hornet of VFA-27, the Royal Maces. The Super Hornet’s raging shark mouth artwork is the very essence of aggression and anger. Photo: Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Charles Oki, US Navy

As witnessed in previous images, the Soviets seem often to prefer more of a crocodile-style mouth than a shark mouth. Regardless, this Tupolev Tu-22 Blinder at Engels Air Base Museum takes the award for the worst-ever shark mouth paint job. Photo: Wikipedia

The starboard engine air intake of this Tupolev Tu-22M Backfire, a later and more capable development of the Tu-22 Blinder, seems custom designed to accept a shark mouth and indeed an entire shark—teeth, eyes and gills. One of the better Russian shark designs. Photo via forum.keypublishing.com

No story about shark mouth aircraft by a Canadian could be deemed complete without a picture of the all blue Mako Shark CT-133 Silver Star of Waterloo Warbirds, perhaps one of the best shark mouth schemes flying today. Photo: Reinhard Zinabold

Multi-engined aircraft offer the option of painting the motif on the engine nacelles OR the fuselage nose section. This Beech King Air C-90A trainer of Allied Wings, a division of KF Defense (KF Aerospace) provides flying training support at No. 3 Canadian Forces Flying Training School (Portage la Prairie/Southport Airport in Southport, Manitoba). A number of these aircraft of Allied Wings sport very aggressive looking shark mouths as well as replica nose art from Second World War RCAF bombers such as Ruhr Express. Avro Lancaster KB700, known as Ruhr Express, was the first of the Canadian Lancs to see service in the European theatre. Photo: Reinhard Zinabold

When ten pilots of the Flying Tigers, the American Volunteer Group, started a highly-respected cargo airline immediately after the war, they began with everything from a Budd Conestoga to surplus Curtis C-46 Commandos. They soon graduated to larger factory-fresh aircraft like the Canadair CL-44 and, eventually in the 1970s, they were ferrying troops to Vietnam aboard new DC-8s like this one which sports a shark mouth in honour of its historical roots in the Second World War. Photo: via flyingtigerline.org

A whale shark. By the time Flying Tiger Line was operating Boeing 747 freighters, there were few if any old guard Tigers still in the captain’s seat, but that didn’t stop the use of the shark mouth on this Boeing 747-100. Flying Tiger Line was the very first scheduled cargo airline in North America, lasting from 1945 until 1988 when it was bought by Federal Express. Photo via modellersalliance.com

A shark on the DNA. During the Second World War, the 76th Tactical Fighter Squadron (TFS) was a shark-mouthed P-40 Warhawk squadron. Like its predecessor, the P-40, the LTV A-7 Corsair II was a nimble, open jawed, low level, light attack aircraft, much loved by its pilots and as such is a natural for the shark mouth treatment. This “SLUFF” (for Slow Little Ugly Fat F__ker) from the 76th TFS is seen dropping ordnance at a range near Eglin Air Force Base in 1980. Photo via Pinterest

Shark-nado! Since the days of the P-40s in the North African desert, nothing says Royal Air Force desert campaigning like a shark mouth light bomber in desert camouflage. On the 25th anniversary of the RAF’s operation of the Panavia Tornado GR in 2016, they went with a shark mouth and the desert pink over-wash of Operation GRANDBY from the First Gulf War. Photo: Niall Paterson

It makes no difference what type of aircraft, there is a predator inside waiting to get out, like this Lockheed C-130 Hercules photographed in 2009 at Hill Air Force Base in Utah. Photo: Herbert Welmers

When Airbus recently introduced its new generation A320s with winglets (also as an upgrade to older models), they called the devices “Sharklets”. The corporate test and promo aircraft also featured a happy shark mouth motif to go along with the wing tips. The company said: “Airbus has launched the Sharklet retrofit programme for in-service A320 Family aircraft. This option will be available in 2015. Operators of older in-service A320 Family aircraft will thus be able to benefit from the significant cost savings and performance improvements which the Sharklets are already delivering on new-build aircraft. This retrofit includes reinforcing the wing structure and adding the Sharklet wingtip device. As part of the upgrade, the retrofit will lengthen the aircraft’s service life and thus maximise the operators’ return on investment for the Sharklet retrofit.” Photo: Airbus

While the point of a snarling shark mouth is to intimidate or at least demonstrate aggressive resolve, some aircraft, like this wide-body Lockheed L-1011 Tristar from Pacific Southwest Airlines (PSA) were never meant to display a frightening countenance. That being said, it seems difficult for operators to stop themselves from personifying or animating their aircraft. This beaming and slightly goofy smiley-face grin gives the big beast a decidedly happy and helpful character. PSA, which called itself “The World’s Friendliest Airline” painted a similar smile on all of their aircraft (737s, 757s, Airbus 320s, BAe-146s, L-1011s) as a way to express their happy attitude. Photo: Wikipedia

Perhaps the least aggressive aircraft type is the sleek modern sailplane, but still, pilots can’t help adding a little attitude with the shark mouth device. This particular glider, a Schleicher ASW 20, seen here tearing up the beach front at Sidmouth, was lost in 2013 when the pilot was unable to reach a field for a forced landing. It ditched into the Bristol Channel just off shore and the pilot escaped. Perhaps it was the shark wanting to return to its natural habitat. Photo: via YouTube

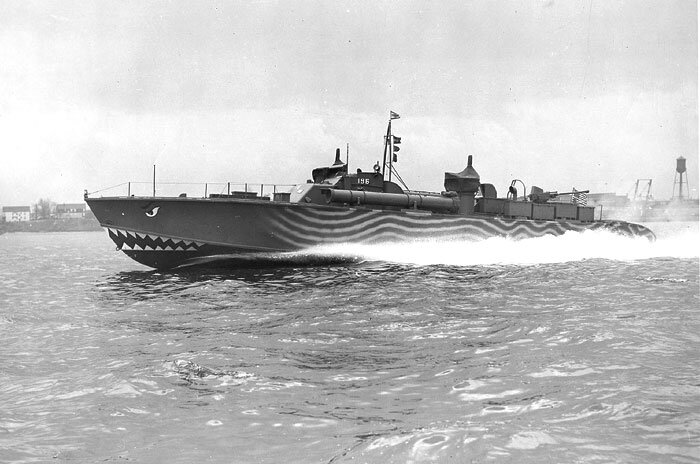

While the air forces of the world may be the services everyone thinks of when picturing the aggressive shark mouth idiom, the navies and the armies also got into the game. Here the US Navy’s PT-196 shows its extremely aggressive shark design at full speed (41 knots). At 80 feet long and with a crew of 17, Elco-built PT-196 was an effective water-based shark indeed. Photo via Pinterest

Here a shark mouth (or is it a tiger mouth?) has been painted on the muzzle flash suppressor of this German SS King Tiger tank near the end of the Second World War. While the mouth may have been small, the bite was most certainly very, very painful. Photo via Pinteres

The shark mouth motif remains today a most enduring symbol of the aggressive spirit, a statement of attitude and pugnacity like no other. It has wormed itself into popular culture and is embraced by western society as a cultural icon. Clockwise from upper left: The helmet worn by the 2016 United States Air Force Academy football team (2 photos), a pair of Air Jordan V P90 Warhawk shoes, a Glock 19 pistol, a snarling Kitchen Aid mixer, a “Kawa-Sharky” street bike and a Nissan GT-R with Flying Tiger attitude. Images via the internet