ROYAL CANADIAN INSPIRATION

I don’t remember if my path was decided that day or whether it took me some time to think about it but I asked lots of questions and soon learned that young boys were eligible to join the Air Cadets when they turned 13 and that the best of them would get the chance to become pilots with free training. From that point on I counted down the years, months and days until I would be 13 and old enough to sign up.

My affiliation with the Royal Canadian Air Cadets goes back to 1964–65 when I was about seven years old. We lived in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia and my father was a member of the Halifax Flying Club. At that time the club was located on Lake William in Dartmouth where the members flew Piper J3 Cubs on floats. Dad had always had an interest in aviation and obtained his private pilot license on Lake William and he was quite active in the club in those years, spending much of his free time either flying the Cub or, most often, doing what pilots do best – hanging around the clubhouse logging “hangar flying” hours. He would often take me along and I remember the stars in my eyes as I watched the planes come and go and as I sat for hours in the pilot’s seat wiggling the controls while dad hung out with his pilot buddies. I clearly remember one such visit when the place seemed to be crawling with young men wearing khaki shirts and pants who appeared to be very busy doing all those mysterious aviation things. On the way home dad told me they were Air Cadets who were learning to fly on scholarships they were awarded through the Royal Canadian Air Cadet League.

As soon as I turned 13 in 1969, I joined 18 Dartmouth Squadron, which at the time met at the Prince Arthur School. I remember talking a number of my friends into joining up with me but over time they all drifted away and within a year I was the only one left. I had one objective when I joined, and it was to win the scholarship to get my pilot's license. I don’t remember ever having any doubts that I would do it.

My uncle, Father John (Jack) MacGillivray, was an RCAF Chaplain and a lifelong airplane nut. Whenever he visited, he and my dad quite naturally talked about airplanes and I was always fluttering about listening to every word. Father Jack was an early member of the Experimental Aircraft Association and, starting in the late 1950s, he flew to the annual EAA convention, first in Rockford, Illinois and later in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. His first aircraft was a de Havilland Tiger Moth (which was eventually donated to the EAA and is now in their Oshkosh museum) followed by a Miles Hawk, then a de Havilland Puss Moth (now in the Canadian Aviation Museum in Ottawa) and finally a Taylorcraft.

The Halifax Flying Club around the time of Jack Neima's early flying experiences with his father and uncle. Photo via Jack Neima

Young Jack Neima hung around the Halifax Flying Club, soaking up aviation in all its surrounding culture... waiting for his 13th birthday and the chance to join the Royal Canadian Air Cadets. Here he attempts to look cool standing on the wheel of a 1943 Aeronca L-3/O-53B Grasshopper. Photo via Jack Neima

The Aeronca L-3 (C-FYYS) from the previous photograph still exists today, restored and repainted as a USAAC warbird – the L-3 Defender. C-FYYS is presently owned by Adam Wagstaffe in Oshawa, Ontario. Photo via Adam Wagstaffe/Airport-Data.com

Father Jack MacGillivray had a passion for flying and obtained his private pilot’s license in March 1956 while stationed with the RCAF in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. He had logged very little flying time in a Cessna 140 when he acquired Tiger Moth CF-IVO. Regardless of experience, he set about to explore his immediate surroundings in Canada’s Maritime Provinces with short cross-country hops to places like Charlottetown, Moncton, Fredericton, and New Glasgow.

By the summer of 1959, MacGillivray was ready to spread his wings. With a fresh membership in a new organization called the Experimental Aircraft Association, he decided to venture off to the annual EAA convention and fly-in at Rockford, Illinois. This was a serious undertaking for a low-time pilot on his first long trip in an aircraft that by today’s standards was very under-equipped. Navigation was by dead reckoning and compass and the trip was made without radio communications. He departed Moncton, New Brunswick on 3 August and arrived at Rockford on 8 August with stops at fourteen towns in Canada and the U.S. While at Rockford, he had the opportunity to meet a number of EAA pioneers who were to become close friends in the decades that followed. These included Marty and Ruth Haedtler, Paul Poberezny, Steve Wittman, and, as he said at the time, “more swell people than I can remember.”

After a two-day visit to the Rockford Fly-In, Fr. John reversed his route and returned to Nova Scotia arriving there on 13 August. The trip lasted 10 days and he logged 39 hours and 40 minutes, but it was the start of a lifelong love affair with EAA. Apart from a two-year posting to Germany, he never missed an EAA convention until his death in 1995. Father Jack MacGillivray’s account of that first trip to Rockford appeared in the October 1959 edition of Sport Aviation and it describes vividly the experience and the emotions he felt.

Related Stories

Click on image

Father Jack's beautiful de Havilland Tiger Moth was painted navy blue overall with white striping and bright red wing struts. Photo via Jack Neima

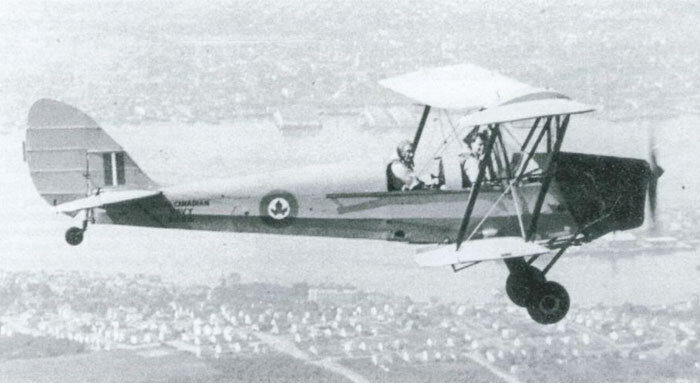

Prior to Father Jack owning Tiger Moth CF-IVO, it was part of the build-up to establish technical training for air mechanics of the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN). The Tiger Moth was acquired along with two other ex-Royal Canadian Air Force D.H.82C Tiger Moths from civilian sources. The first Tiger Moth served with Fleet Requirements Unit 743 providing support to the fleet, while the remaining two were maintenance trainers. In 1949, two Tiger Moths were retired from the RCN and the third was dismantled and placed in storage. In the summer of 1954 it was reassembled and used as a general utility aircraft until finally being struck off RCN strength in November 1957. This aircraft was acquired in mid-1958 by Father John MacGillivray, a Roman Catholic Chaplain based with the RCAF at Summerside, Prince Edward Island. The Moth was registered as CF-IVO and was painted navy blue with white wings and accent trim and red wing struts.

EAA’s de Havilland D.H.82C Tiger Moth is one of the earliest aircraft in its collection, having been donated by Royal Canadian Air Force Chaplain Father John MacGillivray (EAA 3974) following the 1964 EAA Convention and Fly-In at Rockford. Photo by Dave Richardson via Air-Britain photographic Images collection and the EAA

A close-up of the dedication panel on the side of the EAA Tiger Moth in honour of Father John “Jack” MacGillivray. Photo via Jack Neima

Young Jack Neima (right) steps into the front cockpit of his uncle's, Father Jack McGillivray, magnificent Miles Hawk Major (C-FNXT) at the Halifax Flying Club. The Miles Hawk had been imported to Canada from England by the RCAF Chaplain and early member of the EAA during his two-year deployment in Germany. Having such a rare and exotic aircraft as the Hawk air racer in Halifax must have been very exciting for young Neima. Photo via Jack Neima

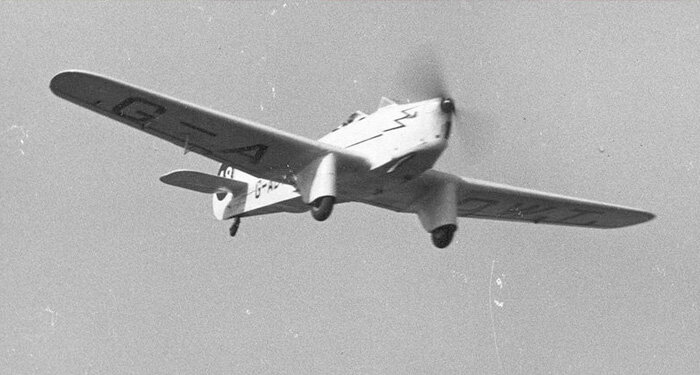

Father McGillivray's C-FNXT was originally an air racer in England – a Miles M.2W Hawk Major (G-ADWT), entered by Cartwright Hamilton Aviation Ltd (the name can just be made out on the fuselage) and piloted by R Dunster. It was entered in the Kelmsley trophy division for aircraft exceeding 130 mph and under 160. Records seem to indicate that it did not complete the race it was entered in. This image was taken in 1954. Photo from Tony Clarke Collection via David Whitworth Collection/Flickr

Miles M.2W Hawk Major Trainer G-ADWT racing at Leeds (Yeadon) Airport. It is believed that Father Jack purchased the Hawk while on a two-year deployment with the RCAF in Germany. The company that owned G-ADWT, Cartwright Hamilton Aviation, was a subsidiary of Fairey Aviation. The little trainer is famous for having made the last known fixed wing landing at RAF Heston... some year after the base was shutdown. Photo via Ruth A. Scholefield, via Wikipedia

Later, in 1964, the Miles Hawk Major G-ADWT wore a different pain scheme altogether. Photo from Tony Clarke Collection via David Whitworth Collection/Flickr

After its ownership under Father Jack McGillivray, the Miles Hawk C-GNXT was repatriated to England where today she still flies with her original registration G-ADWT. She is owned by B. Morris and R. Earl and operated from The Shuttleworth Collection, Old Warden, Bedfordshire, England. Photo by John Allan

The beautiful Miles Hawk Major taxies on the manicured grass of Old Warden, the home of the Shuttleworth Collection. Photo: Robert Beaver

Complete and total restoration of G-AWDT was completed in 2003 by the Newbury Aeroplane Company, UK. It is presently for sale. The beautiful Hawk is one of only 12 manufactured and the only one flying worldwide today. Originally, the trainer was delivered new to Phillip and Powis (the original name for Miles Aircraft) and then to No.8 Elementary and Reserve Flying Training School at RAF Woodley. Photo by John Myers

No matter where Fr. Jack was based in the Air Force he always came home to Nova Scotia each summer for a visit following the annual EAA convention and during those visits we got to see all of the movie films and snap shots that he took during the fly-in. I studied the pictures and listened intently to all of his stories and over the years I too became more and more knowledgeable about aviation and I remained inspired and focused on my goal of learning to fly.

As dad’s flying experience increased he also became an aircraft owner and, at one time or another, owned outright or with partners an Aeronca 7AC, a Piper Tri Pacer, and a Fleet Canuck. Being around these planes and having the opportunity to fly in them with dad kept my dream alive. I could easily close my eyes and see myself at the controls of an airplane, most often a bright yellow J3 Cub on floats which was always my idea of the perfect airplane.

Jack Neima's father helped him reach his goal of flying by directing him into the Air Cadet program, where he learned the benefits of hard work, discipline and focusing on his ultimate goal. Here, dad poses beside Jack's Piper J-3 Cub at the Stanley, Nova Scotia airport. Photo via Jack Neima

I would not be eligible to apply for the flying scholarship until I was 17 so, like all cadets I “served my time.” I participated in all squadron activities and worked my way through the ranks. I remember how proud I was when I got promoted to corporal and had the opportunity to take on some responsibility. I went to the Air Cadet Summer Camp at Greenwood during my first year and for some reason was fortunate to be able to do a specialized course (Physical & Recreational Training – P&RT) rather than the typical basic cadet training. That first summer I had the chance to fly twice on “famil rides” – first in a Canadian Forces de Havilland Otter and second in an Air Cadet glider, a Schweitzer 2-22. I’m not sure when the cadet glider program started but I think it may have been around that time and it was not then the extensive training program that it later became. The gliders were winch launched from the grass along the north side of Greenwood’s runway and I think the whole purpose of the program was to give air cadets their first hands-on experience with flying.

In subsequent years I continued to work my way through the ranks and every summer I participated in more and more specialized training programs such as Junior Leadership, Senior Leadership, etc. Finally in 1973, I turned 17 and immediately applied for the Flying Scholarship. At that time there was only one scholarship – for the powered pilot license. I successfully passed the tests and screening and at the Squadron’s Annual Inspection that May I was awarded the scholarship with training taking place in July and August at the Halifax Flying Club, which by this time had relocated from Lake William and was now operating out of the Halifax International Airport and equipped with Piper Cherokee 140s and Grumman American AA1A “Yankees”. By now I was a Flight Sergeant.

Air cadet Flight Sergeant Jack Neima is awarded his flying scholarship by an RCAF officer and pilot in May of 1973. Photo via Jack Neima

In 1973 my father was on the Board of Directors at the Halifax Flying Club and I was well known by the instructors and staff there. When they learned that I would be part of the cadet training class that summer I was contacted and offered the opportunity to get started early. I jumped at the chance because the training program did not officially start until early July, when the group of a dozen or so cadets arrived from all over Atlantic Canada. By the time they did get there I was a few hours into my flying training with instructor Gary Hamblin, who was the son of another Flying Club director, Ike Hamblin, a close personal friend of dad’s. As a result of my favoured treatment I was always a little bit ahead of the group and consequently throughout the program I was the first to do everything. The first to solo, the first to spin, the first to fly cross-country, the first to flight test and it sure made me feel special.

I clearly remember the first day of the official program. We were assembled in the classroom and we were addressed by the Club’s President, Dr. Wylie Verge. He encouraged us and wished us all the best of luck and he advised us that the Club was offering two prizes to the cadets for the summer. The first would go to the highest ground school mark and consisted of a check out in Ike Hamblin’s float equipped Aeronca Champ. The second prize would be a check out in the Club’s high performance Piper Comanche 260, a fast six seat retractable speed demon. This prize was kind of a “keener” award and would go to the cadet deemed by the staff to be most deserving based on effort, willingness to pitch in and help, etc.

I set my sights on the Comanche prize and throughout the summer I busted my butt to be as dedicated as I could be. I swept out the hangar, helped the mechanics with all kinds of dirty jobs, pushed planes all over the ramp, refuelled, washed windows, cleaned up spills, – you name it. No one was going to beat me to that prize!

Training progressed through July and August of 1973 and it was a terrific experience for me and for the other participants. I have a number of vivid memories from that summer. There were two groups of cadets doing flying training in Nova Scotia that year, my group at the Halifax Flying Club and another at the Shearwater Flying Club. Both groups were billeted at the Shearwater naval air station, which I was pretty well familiar with because by that time my home squadron, 18 Dartmouth, had relocated to an old hangar complex near the Shearwater jetty. The other group was billeted at the Warrior Block on the main base but for some reason that was unknown to us it was decided that we would not be placed with them. At that time there were three mothballed Navy destroyers docked at Shearwater. They were HMCS St. Laurent, HMCS Ottawa, and HMCS Fraser. The ships were used that year as a summer training camp for the Royal Canadian Sea Cadets and at any one time over the course of that summer there were a couple of hundred sea cadets living on the ships and involved in whatever nautical training sea cadets did in those days. Anyway, for some reason, it was decided that my Halifax Flying Club group of Air Cadets would be billeted aboard HMCS Fraser so it became my home for the summer. We ate breakfast and supper in the on-board mess with the sea cadets and we carried box lunches on the bus out to the Halifax International Airport each day. It was quite an adventure and, as I look back on it, I think it added a lot to what was already a pretty fantastic experience. I don’t remember there being any friction between the sea and air cadets.

HMCS Fraser (DDH 233), Neima's home in the summer of 1973, was a St. Laurent-class destroyer that served in the Royal Canadian Navy and later the Canadian Forces from 1957–1994. Fraser was the last survivor of the St. Laurent-class destroyers which were the first Canadian designed and built warships. RCN Photo

Sadly, HMCS Fraser, the last remaining St. Laurent-class destroyer rotted on a Bridgewater, Nova Scotia pier for years as authorities decided her fate. Would she be a museum ship? Would she be a sunken reef? Was she a historic site? Unfortunately, as time went by, her restoration costs would grow and, eventually, she was towed to Ontario and broken up. The editor's brother served aboard Fraser in the late 1970s as a young signals rating.

Because of my head start I got to be the first cadet to solo. Every pilot I have ever known has fond and vivid memories of their first solo and in many respects my story is similar to the experiences of others but there were a couple of notable exceptions. No one else had soloed yet so I had no idea what to expect. After a routine flight out to the Shubenacadie training area, Gary had me shoot a couple of touch and goes and then asked me to taxi back to the ramp. During previous flights he would often jump out and head for the office as soon as we got on the ramp leaving me to complete the post-flight checks, shutdown, and then come inside to debrief the lesson. On this occasion he got out on the wing, leaned back in and told me to have a good flight. The only thing I remember him saying was that the plane would feel a lot different without his weight but that I was ready. He slammed the door and waved me off.

I knew I was ready for that first solo but it came upon me so fast that I never really had a chance to think about it in advance. I taxied out and did the usual run-up and pre-takeoff checks and called tower for clearance to take off for the circuit. I was cleared to take off and away I went. Gary was right, the plane was much lighter and the performance was notably different. I clearly remember singing and talking to myself on downwind for that first circuit and I just couldn’t believe that I was doing this on my own. That first circuit was as good as any I had flown before, maybe even since, and I did a touch and go. After a couple of more circuits I got a call from tower saying they wanted me to make this a full stop and bring the plane back to the ramp. It never occurred to me, and Gary never said, that the first solo was supposed to be one circuit.

I remember taxiing back to the ramp and that great feeling of accomplishment that washed over me. I was a pilot and I had flown an airplane all by myself and here I was now bringing it back in one piece. How cool is that?

I knew a little about the first solo traditions of shirt tail cutting and drenching with water but there had never been any discussion that I was part of about how those traditions would be observed for our group. I remembered all those times back at Lake William when first solos were observed by throwing the trainee bodily into the lake. As I taxied in I thought about that and was aware that something was probably going to happen. After shutting down I got out of the plane and I could see some of my fellow students hiding behind other parked planes. The door to the office was about 30 feet away and above the door was a window to the Club’s second floor lounge. The window was open and one of the cadets was there with a garbage can I assumed was full of water. Don’t ask me why but I didn’t want to get soaked and I reasoned that if I ran I could avoid the guys on the ramp and get through the office door before the guy upstairs had time to unload. Not a good plan but the only thing I came up with so I was off. I hit the door going full out, turned the knob and kept running. The door was locked. I bounced off the door and was immediately doused with about 10 gallons of water from above and then pounced on by lots of people armed with fire extinguishers. They “got me good” but I had a problem... when I tried unsuccessfully to turn the door knob the momentum of my body weight had been taken up by my right wrist and I remember hearing it snap. Boy, did that hurt! I knew I had done some serious damage so they bundled me up and we headed for town. Dad met us at our family doctor’s office. The doctor just happened to be Wylie Verge, who was also the president of the Halifax Flying Club. To make a long story short, it turns out that my wrist was indeed broken and it would need a cast. Luckily for me I was able to get the most odd shaped cast that gave me enough finger movement that I was able to reach all of the various switches and levers in the Cherokee and I went on to finish my flying training and flight test with the cast on my arm. Needless to say, the second and subsequent solos in our group were recognized in a much less dramatic fashion!

I successfully passed my flight test in late August and finally became a fully licensed private pilot fulfilling the dream that had started about 10 years earlier on the shores of Lake William. At our graduation ceremony they awarded the prizes and guess who won the Comanche check out? What a thrill that was and I still can’t believe that they let a 60 hour, 17-year-old pilot fly that plane. Wow!

Jack Neima's mother pins his new wings on him at a ceremony in September of 1973. Photo via Jack Neima

Young Jack in civvies and beaming with pride in his cadet uniform on the occasion of his wings ceremony. Photos via Jack Neima

In those days cadets who successfully completed the Private Pilot program had the opportunity to go on during their next summer to obtain the glider license. Participants were taken on as paid summer employees of the League with the rank of corporal similar to other staff cadets. Today, the program is reversed – cadets often get their glider license during their 16th year and return the following year for their power. As previously stated the glider program in those days was basically a “famil” flight operation at the summer camp at Greenwood. In 1974 I applied for the glider program and was accepted so I spent that summer at Greenwood. With a power license already, the glider training was pretty much just a check out and soon I found myself strapped into a glider taking younger cadets for their first ride. I knew from my own experience back in 1969 what they were thinking and I hoped that the inspiration I received then would be passed along.

In 1974 I graduated from high school and joined the Canadian Armed Forces as an Officer Cadet and pilot trainee under the Officer Candidate Training Program (OCTP). After basic officer training at CFB Chilliwack, British Columbia I was transferred for a 6 month “OJT” stint with VP415 Squadron in Summerside, Prince Edward Island. My pilot training course at CFB Portage la Prairie, Manitoba was scheduled to start in September. 415 Squadron was tasked with anti submarine warfare and long-range patrol using the Canadair CP-107 Argus. As the summer of 1974 rolled around I was getting bored sitting around the squadron operations room so I spoke to the adjutant and asked if it was possible to be seconded to the air cadets and serve out the balance of my OJT time flying gliders at Greenwood. The adjutant made a call and to my delight my request was approved so I spent the summer of 1974 as a full-time CAF Officer Cadet flying gliders with my old cadet buddies.

I left the CAF in 1976 to accept a position with the Royal Bank of Canada from where I retired in 2011 after 34 years of service. During that time I maintained contact with the Royal Canadian Air Cadets, first as a civilian instructor with 333 Lord Beaverbrook Squadron in Fredericton, New Brunswick and later as part of the Sponsoring Committee at 693 Sydney Rotary Squadron in Sydney, Nova Scotia.

I have four children and all of them are graduates of the air cadet program, each reaching the rank of CWO in their respective squadrons. My two daughters, Nadine and Keri, each received glider and power scholarships and obtained their pilot licenses. Keri now works at NavCanada as a Flight Service Specialist in Churchill, Manitoba and she and my son Jon are members of air cadet squadron staffs in their home communities. My granddaughter, Gabrielle, is now a corporal at 29 Squadron in Sydney, Nova Scotia.

I purchased my first aircraft, a Piper Tomahawk, in 1985 and have been an aircraft owner continuously since then. The Tomahawk was replaced by an Aeronca L3, then a C172 and a Piper J3 Cub. I still own the Cessna and the J3 which is equipped with wheels, skis, and floats and I am also working on the restoration of an Aeronca 7AC Champ. The airplanes are based at Stanley Airport, Nova Scotia.

Jack and his son Peter pose with his first airplane – a sleek Piper Tomahawk (C-GRZW), seen here on the frozen surface of a Nova Scotia lake. Photo: via Jack Neima

As I think back I remember what an important part of my life my air cadet career was. It provided me with a very solid foundation during those critical teenage years. I learned a lot about leadership and responsibility, both personal responsibility and responsibility to my community and to others. But it goes beyond that… being a cadet kept me on the right path and steered me around many pitfalls that came my way. Like every other teenager at the time I was exposed to temptations and challenges and I remember seeing many of my friends succumb to these temptations. Through it all I kept one objective clearly in mind – to win an air cadet flying scholarship – and every time I was faced with a challenge I remember evaluating it on the basis of the impact my action would have on my ability to achieve my goal. I won’t go so far as to say I was obsessed with obtaining that scholarship but as I look back I understand more clearly now than then how it served as a guiding influence. Years later, throughout my career as a banker, I held various leadership roles, including one position where I had more than a thousand people reporting up to me, and I was able to apply many of the lessons I learned as an air cadet on how to lead teams of people.

I also realize that their cadet experiences are responsible to a large extent for the fact that all four of our children have developed into very responsible and mature adults who are each contributing to their communities and giving back in their own ways. I am proud to see this continuing into the next generation through my granddaughter and I will be delighted to see the rest of my grandchildren following in her footsteps when they are old enough to join.

Jack's daughter Nadine at the controls of an Air Cadet glider in Nova Scotia. Photo via Jack Neima

What goes around comes around. Jack Neima (left) and his father on the occasion of his daughter Nadine's wings parade. Photo via Jack Neima

Jack's three children all were accomplished air cadets. Left, daughter Keri in 2004, right: children Peter and Nadine of 693 Squadron. Photos via Jack Neima

I consider myself so fortunate to have achieved my goal of learning to fly through an Air Cadet scholarship and to realize all these years later that I am still reaping the rewards. I am indebted to so many people for making all of that possible and I am eternally grateful for all that the Royal Canadian Air Cadet league has done for me and for generations of my family.

Jack Neima, Porters Lake, Nova Scotia, February, 2013

Jack and his daughter Keri enjoy the joys of flying in all four seasons with their Piper Cub on floats, wheels and skis. Photo via Jack Neima

Jack Neima has enjoyed a lifelong flying career thanks to the Royal Canadian Air Cadets. Photo via Jack Neima