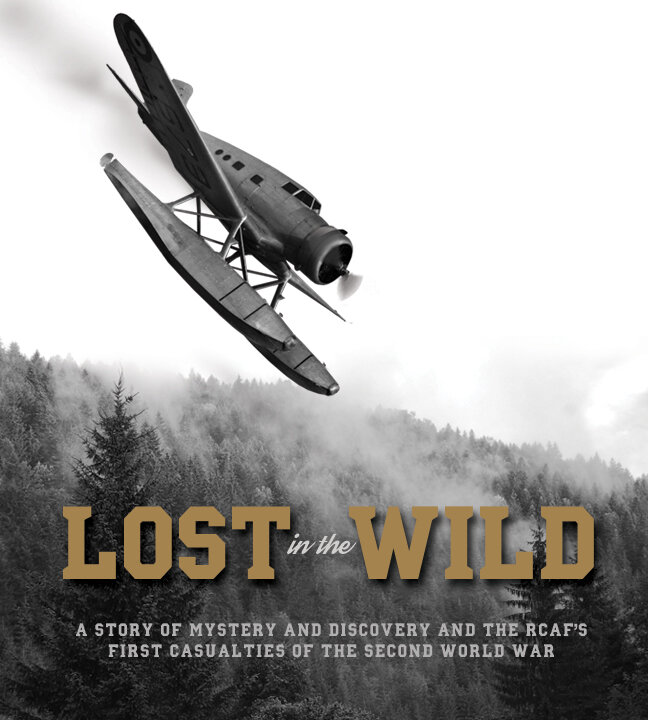

LOST IN THE WILD

Two Royal Canadian Air Force airmen would become the first to die in Canada in the Second World War, but they would not be found until 1958.

Canada is a very, very large country. Most of it is unpopulated. In 1939, it seemed a lot bigger and a lot less populated. Much of the country then was uncharted and wild, accessible only on foot, by canoe or by float plane, and unseen by human eyes.

One just has to drive across the centre of New Brunswick, one of Canada’s smallest provinces, to understand the vastness of the entire country. If you head east out of the small town of Plaster Rock along old highway 108, bound for the Miramichi River community of Renous, you will enter a vast uninhabited tract of forested wilderness, the size of Kuwait. Beaten by logging trucks and hard winters, the narrow two-lane blacktop surface of NB 108 curves, climbs and drops through an apparent wild and even monotonous landscape. A few hundred metres in from the road on both sides, the hollow scars of intense clear-cut logging can be seen flickering like light through the trees and from high ridges. Great swathes of this woodland have been logged out and replanted and yet this is truly a wilderness, a place you enter with a full tank of fuel and where you don’t want to have a breakdown of your car. It’s the perfectly remote spot for the maximum security prison at Renous. The wild is but a right turn away. In 1939, it was far wilder—a forbidding place to overfly in a single engine airplane.

In the summer of 1939, Europe was accelerating towards war. Every person in every country in the continent felt the gravitational pull of the impending maelstrom, a black hole of chaos and inevitability. Throughout the far corners of the British Commonwealth (at one time the Empire) politicians, military leaders and ordinary citizens could sense the coming storm. While isolationist America turned its back to the European war, Canada knew its loyal duty was to rally to the Union Jack and the King. But they were very far from ready.

That summer, the Royal Canadian Air Force had little to offer in the way of fighting capacity should it be required, but military planners were already creating the systems, equipment and alliances that would result in enormous expansion and a mighty contribution to the successful expedition of the war. The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan was signed into existence that summer, and contracts were signed from coast to coast for aircraft, equipment, facilities, training airfields and instructors, but it would take months to get rolling in earnest. In the meantime, existing squadrons of the Home Establishment were put on alert in the defence of the nation.

The most important and most immediate need was the security of the East Coast of the country. While no one expected an invasion, experience in the last war had shown that German U-boats were a major threat to coastal shipping, to the convoys that were inevitable in the event of war and even fishing. At the outset of the war, the RCAF was replacing a small fleet of Canadian Vickers Vancouver flying boats with the more capable Supermarine Stranraer, which would see solid service on both Canadian coasts for the duration of the war. To reinforce the anti-submarine patrols along the coast and out over the Atlantic Ocean, the RCAF pressed into service the Northrop Deltas of 8 Squadron, a photographic survey unit based that summer at RCAF Station Rockcliffe on the shores of the Ottawa River, just a few miles from Canada’s Parliament.

A fine photograph of an RCAF Northrop Delta (RCAF serial No. 667) on floats demonstrates the size and attractive lines of the type. Delta 667 is the first of twenty Canadian Vickers-built Northrop Deltas taken on strength by the RCAF. Photo: RCAF

Judging from the mountainous background, this photo was taken at Vancouver’s RCAF Station Sea Island, where Delta 675 first served with No. 1 (Fighter) Squadron as a transitional trainer when the squadron converted from the Armstrong Whitworth Siskin to the Hawker Hurricane. Both the Hawker Hurricane and Northrop Delta were manufactured under licence in Canada for the Royal Canadian Air Force—the former by Canadian Vickers in Montréal, Québec and the latter by Canadian Car and Foundry (CCF) in Port Arthur, Ontario (today’s Thunder Bay). Both would define the early Home Establishment presence of the RCAF during the war. The Hurricane in this photo is not a CCF-built Mk XII, but rather an early Mk I, shipped from Great Britain to equip two coastal fighter squadrons. Close examination of the photo (in its original size) revealed that the RCAF serial number on the Hurricane might be 317. This aircraft was lost near Mission, British Columbia en route to Calgary on 8 June 1939. Photo: RCAF

A lovely photograph of two RCAF Northrop Deltas (676 and 677) along with a Noorduyn Norseman (678), very likely at Sydney. It is interesting to note that all three were Canadian-built (Montréal, Québec) and that their RCAF serials are perfectly sequential. Photo: RCAF

The Northrop Delta was not designed as an anti-submarine aircraft, and in the end would prove to be entirely unsuitable for the job, but it was the most modern aircraft in the RCAF’s fleet. The Deltas were built under licence from Northrop by Canadian Vickers of Montréal. A total of 20 were built specifically for photographic work and delivered to the RCAF starting in September of 1939. Originally designed as a passenger transport aircraft, the Delta was a low wing, single engine, tail-dragging monoplane of considerable weight and power. It was the first all-metal aircraft to be built in Canada. The type was kitted out for photographic work with camera mounts and ports, and pilots were trained to hold steady and stable courses for aerial photography. A versatile aircraft for the Canadian environment, the Delta could be operated on wheels and skis and had the power needed for float operations. Pilots were required to have skills in all three landing systems.

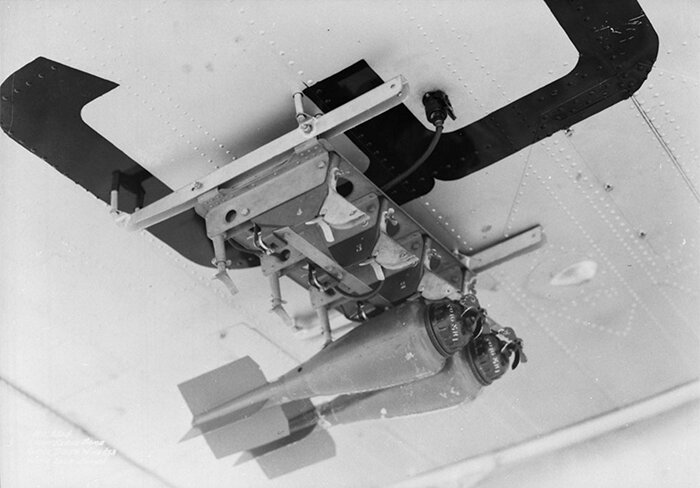

The RCAF must have thought that one day the Deltas might be needed for a fight, for in the winter of 1938–39, one of the Deltas (RCAF Serial number 673) was modified for combat, and tested with bomb racks and even a Lewis gun firing from a ventral camera port. In the event of war, the float-equipped Deltas could now be modified as reconnaissance and patrol aircraft.

The RCAF chose the Northrop Delta for aerial survey work for its robust structure and capacity of work on floats, wheels or skis. The Deltas had only been in service for a few years when the RCAF pressed them into service as coastal patrol aircraft. Here we see Northrop Delta 673 (the same aircraft flown by Doan and Rennie on their last flight) in the winter of 1938–39 at Rockcliffe, being tested with bomb racks under the centre and outer wing sections. A Lewis gun was also fitted firing downward through a camera port in the rear fuselage. How this would worry a submarine on the surface is not known. The Deltas would prove poor coastal and anti-submarine aircraft as they were prone to salt corrosion and were easily damaged by ocean swells. Two months after entering service at Sydney as float planes, they were withdrawn to the shore and operated from wheels. Two years later, the type was withdrawn from service entirely and relegated to instructional airframe status at British Commonwealth Air Training Plan schools. Photo: RCAF

Related Stories

Click on image

On 25 August, with German armour and infantry massing on the Polish border, the call to mobilize was sent and 8 General Purpose (GP) Squadron began immediate preparations for departure to the East Coast. Men were called up, pilots briefed and on 26 August, the seaplane base on the Ottawa River below Rockcliffe was busy with float-equipped Deltas being serviced on land, lowered down the ramp by wheel bogie and cable and moored on the river, ready for the scheduled departure the next day. Out on the river, RCAF motor launches raced from aircraft to aircraft with mechanics and tools. By end of day, all six Deltas were moored out on the river and ready for an early departure the next morning, 27 August.

Crews (a pilot and mechanic for each of the six aircraft) had begun assembling at Rockcliffe the night before. The pilot of Delta 673 was Warrant Officer Second Class (WO2) James Edgerton “Ted” Doan, originally from Vancouver, but now living in Ottawa with his wife Vera and two sons. Doan came up through the ranks, first as an engine fitter and then cross training to be a pilot. He was highly experienced with 1,400 hours in his logbook and was considered a steady and reliable pilot.

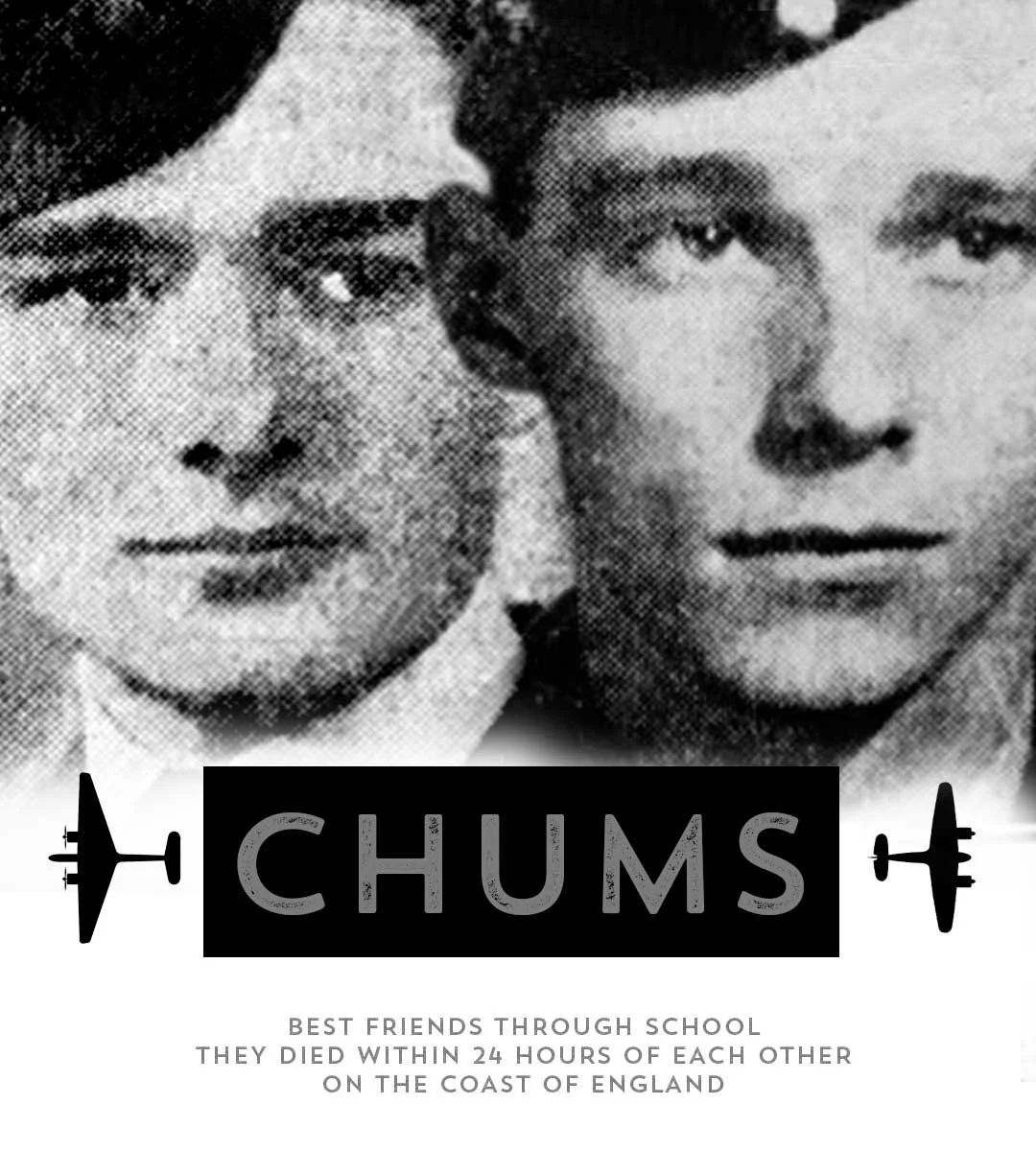

Two of the Royal Canadian Air Force’s pre-war members would lose their lives in a mysterious crash shrouded from view for nearly two decades. The pilot of Northrop Delta 673 was Warrant Officer James Edgerton “Ted” Doan (left) of Ottawa and aircraft mechanic Corporal David Alexander Rennie of Ottawa. In their attempt to get to Sydney, Nova Scotia for anti-submarine duties, these two would be the first of many Canadian casualties of the war to die on Canadian soil. Photos via Mystery Plane Found in New Brunswick by James Cougle

Everyone in the squadron knew they were headed to the East Coast, but most assumed Dartmouth, Nova Scotia across the harbour from Halifax. The final destination was not revealed until the early morning briefing on the 27th. It was then that the pilots knew they were flying together to the city of Sydney on Cape Breton Island. Doan’s mechanic crewmember for the long journey was to be Corporal Guy LaRamee, but a mix-up during the hurried preparations brought him a young mechanic by the name of Corporal Dave Rennie instead. Rennie, a young and capable mechanic, was from Ottawa, growing up in the area known as the Glebe. He had a girlfriend by the name of Lillian Watterson who had driven him to Rockcliffe the night of 26 August.

When the six pilots of 8 Squadron took off into a rising sun on the cool morning air at 8:30 a.m., the Ottawa River valley reverberated with the float-amplified sound of six powerful Cyclone-powered Deltas at full power climbing heavily into the day. All six pilots would rely on keeping with the group and map reading if separated. They had no radio communication equipment. They were still a General Purpose squadron, but when they landed, they would become a General Reconnaissance and then a Bomber Reconnaissance squadron. The planned route to Sydney called for them to fly across Montréal, the Eastern Townships region of Québec, the rugged forests of central Maine and New Brunswick, landing to refuel at the Shediac, New Brunswick seaplane base on Northumberland Strait. From there they would follow the north shore of Nova Scotia and cross Cape Breton Island, landing at Sydney where their war was to begin. At a cruising speed of 150 mph at 3,000 feet, the 950-mile trip to Sydney would take 6 1/2 hours total flying time. Only five of the six aircraft would make it.

Northrop Delta 676 of No. 8 Squadron is serviced by an RCAF launch at a mooring on the Ottawa River near RCAF Station Rockcliffe in Ottawa prior to departing for Sydney, Nova Scotia. This was the same place from which Delta 673 began its arduous and ultimately fatal attempt to get to Sydney. The date stamp on this photograph indicates 26 August 1939, the day before Doan and Rennie departed with five other Northrop Deltas from Rockcliffe, bound ultimately for Cape Breton. The six Delta floatplanes of No. 8 Squadron RCAF were to be employed as submarine hunters and as such would have nominal bomb racks attached underwing. Originally designated a General Purpose (GP) squadron, the unit was by this time called a General Reconnaissance (GR) squadron. Following their arrival at Sydney, they then became a Bomber Reconnaissance squadron. Though their Deltas were hardly bombers, the unit was also equipped with the much better Bristol Bolingbroke. In the distance in this photograph can be seen another Delta (673?) and a Supermarine Stranraer flying boat, possibly from No. 7 Squadron RCAF which operated them at Rockcliffe during this period. Delta 676 would crash while in Nova Scotia. It was repaired at Canadian Vickers and modified with a larger tail. It would spend the rest of its short service life with similar squadrons on Canada’s West Coast. Photo: RCAF

Another photograph taken at Rockcliffe on 26 August during the preparations for the departure of 8 Squadron’s six Northrop Deltas. Here we see Delta 671 (lowered by cable) on the seaplane ramp at Rockcliffe that leads down to the Ottawa River. 671 was one of the six Deltas that left the next day for Nova Scotia. Piled wheel sets at the ramp’s edge indicates that other Deltas have already been brought down from the airfield and put in the water. Delta 671, flown by Flight Sergeant W.C. Pate, would come to the rescue of 673 the very next day at Salmon Stream Lake, Maine. This ramp is still in use today. Photo: RCAF

While well over the rugged wilderness of Maine, having just flown over the mill town of Millinocket, one of the six Deltas, No. 673, dropped out of the loose formation and descended towards the forest below, looking for a lake on which to land. Below them was Salmon Stream Lake, and Doan made a smooth emergency landing and taxied up to the shore. Being able to taxi the float plane on the surface meant 673’s engine was generating some power and that the engine did not completely quit. Doan’s smooth, well-set up landing also indicated some residual power. Seeing Doan descend and land, Flight Sergeant William C. Pate and Corporal Guy LaRamee in Delta 671 followed Doan and landed on Salmon Stream Lake, taxiing alongside him at the shoreline. After investigating the problem with the engine, the four men, all experienced mechanics) decided that one of 673’s seven cylinders would need a replacement before they could continue on to Sydney.

Pate and LaRamee left for Sydney to arrange for a new cylinder, while Doan and Rennie prepared the Delta for the work ahead and settled into a fishing and hunting camp they found on a small island. After two long nights waiting, Flight Sergeant Bob Thomas arrived on 29 August in Delta 676 with the cylinder and tools. The four men replaced the cylinder and determined that the engine should be replaced at the soonest possible chance. By the afternoon of the next day, the work was complete on the single cylinder and they took off for the remote Norcross seaplane base, 17 miles to the east. Here they cleaned up, rested and wrote a report on what happened that was submitted to the operations manager at Rockcliffe. It stated that the crew felt the source of the problem was a “faulty muff installation”. In retrospect, this is a strange entry on the form, given that they got underway to Norcross in the late afternoon of 30 August following the installation of a new cylinder and not the muff heater. The muff heater is essentially an exhaust heat-exchanger and collector shroud that sent air heated by the exhaust piping to both the carburetor (to prevent icing) and the cabin. The device is still in use today in many aircraft. One of the most serious problems resulting from a cracked or damaged muff heater is exhaust gas that is drawn, along with heated air, back into the engine induction system via the carburetor. This can cause engine overheating and loss of power. There is no indication from the report submitted that the muff heater was repaired or adjusted, though it was mentioned as the probable cause.

Doan and Rennie contacted Rockcliffe and awaited instructions on where they should proceed—on to Dartmouth or back to Rockcliffe for a new engine. With family and girlfriend in Ottawa, the two men hoped that they would be required to return to Rockcliffe. Towards the end of the day on 30 August, they received orders to return to Ottawa for the necessary engine change, with a fuel stop at the sea plane base at Lac Mégantic on the Québec–Maine border.

The flight to Lac Mégantic on the morning of 31 August was uneventful, but shortly after takeoff after refuelling, the engine failed once again and they landed back on the lake. After examination of the engine and their situation, it was decided that they should do the engine swap on the shores of Lac Mégantic. This of course, was going to take some time.

Doan and Rennie settled in to the Hotel Lake View and took advantage of the excellent food, hot baths and alcoholic refreshments. An engine change on the shores of the lake was going to be a difficult task, requiring the right tools, the engine and a wooden frame to lift the engine. Judging from a photograph of the men during the work, there already existed at Lac Mégantic a trolley and frame to lift the engine from the airframe and bring it on shore. On Friday, 1 September, Doan fired off a telegram to his commanding officer, now at Sydney, Nova Scotia, and requested a new engine and appropriate tools be sent to Lac Mégantic as expeditiously as possible.

The engine work under these conditions was going to be arduous and lengthy and the men were already exhausted. The men set about immediately to secure the engine hoist and trolley and begin the business of removing the failed engine.

Realizing they might be in Lac Mégantic for a couple of weeks, Dave Rennie telephoned his girlfriend Lillian Watterson and invited her down from Ottawa by train for the weekend. There is no indication whether this was the weekend of 2–3 or 9–10 September 1939, but the men would not fly out of Lac Mégantic until 13 September. Doan had no such opportunity with his wife and small children back in Ottawa, and expressed his envy for Rennie in a letter back home: “My crewman had his girlfriend down for the weekend and it made me feel worse…”

At Lac Mégantic, 8 (GR) Squadron Delta 671 arrives from RCAF Station Rockcliffe with a new engine, while in the background, Rennie and Doan prepare 673 to receive the Wright Cyclone. Photo via Mystery Plane Found in New Brunswick by James Cougle

Northrop Delta 673 gets a new Wright Cyclone engine on the rugged shores of Lac Mégantic. Photo via Mystery Plane Found in New Brunswick by James Cougle

Warrant Officer James Doan (left) and Corporal David Rennie are photographed with the engine change rig at the RCAF seaplane base at Lac Mégantic near the Québec–Maine border. The trolley below them would be run down the rails to the beached and engineless Delta. Flying over such rugged territory, the RCAF was wise to have a mechanic accompany the pilot. In fact, both Doan and Rennie were experienced aircraft engine fitters. This is likely the last photograph taken of the two airmen alive. Photo via Mystery Plane Found in New Brunswick by James Cougle

After much hard work, the Delta was ready to test fly on Wednesday, 13 September, more than two weeks after the two airmen had set out for Sydney. Throughout their two weeks at Lac Mégantic, neither Doan nor Rennie expressed any apprehension about the new engine (according to Lillian Watterton), which was fitted with the old muff heater. They were confident in their own abilities and anxious to get to their unit and into the war. On the 13th, they tested the engine in run-ups and taxiing on the lake, then took to the air for a flight test. Everything checked out and Doan telegraphed his commanding officer and informed him that he was planning to leave early on 14 September.

The unit commander sent instructions to Doan about a new course, which, in retrospect, sealed their doom. Because war against Germany had been declared on by Canada on 10 September, it was no longer possible for Canadian military aircraft to overfly Maine, since the United States was neutral and would take more than two years to join the fight. They were required to fly a fairly direct route to the St. Lawrence River, turn northeast at Québec City and follow the river’s flow to the town of Rivière-du-Loup on the south shore of the river in the Kamouraska region of Québec. Upon reaching this point, they were to turn southeast and head for Grand Lake and eventually to land at the seaplane base at Shediac for fuel. The two airmen took off at 10 a.m. that morning and flew north towards the big river. Doan would have been anxious about getting to the St. Lawrence, as there were few spots to put down until they got there.

This new requirement to skirt neutral America meant they would add several hundred miles to their journey to the coast, and be required to fly over long stretches of “dry” central New Brunswick. For obvious reasons, float plane pilots preferred to fly over areas with plenty of water to land on in case, as happened to Doan and Rennie already, they had to make an emergency landing. Flying down from Rivière-du-Loup on the south shore of the St. Lawrence meant flying through the high backbone of the Gaspé region, past the welcome stretch of Lac Témiscouata, overhead Edmunston and angling past the small lumbering and gypsum mining community of Plaster Rock heading southeast. It was here that they would have to enter the vast boreal forest of central New Brunswick, an endless rolling landscape of second growth timber, 100 by 150 kilometres, with little water save for beaver ponds, trout streams and only one lake (Beaverbrook Lake) with any capacity to accept an emergency landing from a Northrop Delta.

The area had been logged out and replanted in the early part of the 20th century, and there would be no need for loggers or prospectors to venture into the area for years to come. There were no roads in those days, no hunter’s cabins and worst of all, little or no chance to land a floatplane safely.

At 0955 hrs on the morning of 14 September, Doan lifted off the still waters of Lac Mégantic and turned towards Québec City to the north. On this day, Doan’s recent promotion to Warrant Officer Second Class became effective. It was five days before his fifth wedding anniversary. His plan was to pick up the massive flow of the St. Lawrence River to the east of Québec, and turn to follow the shoreline. Around noon on that rainy and overcast day, Corporal Arsenault, a Royal Canadian Mounted Policeman, spotted Doan and Rennie overhead Rivière-du-Loup. Doan shaped his course from northeast to southeast, making a 90º turn over the town. The aircraft was low enough for Arsenault to make out the RCAF roundels and serial number (673) under the wings.

A map showing the attempted and actual route of Doan and Rennie in Northrop Delta 673. Clearly evident is the massive deviation from the plan caused by the fact that Canada was now in a war in which America had remained neutral. Had they been able to continue as planned, there is no doubt they would have made it safely to Shediac. Map by Dave O’Malley

In 1939, aircraft sightings were something people paid attention to and remembered details from. Just two years later, the skies over much of Canada would be seamed with formations of the thousands of training aircraft of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, Ferry Command and the RCAF. But in September of 1939, a man who spotted a rare overflying aircraft of the size of the Delta in a remote location remembered the facts of its passing. At around 1230–1300 hrs local time (New Brunswick is in the Eastern Standard Time Zone), a forest engineer by the name of Atkinson reported seeing Doan’s Delta over the small community of Green River (likely Rivière Verte) about 15 miles southeast of Edmunston, New Brunswick. At around the same time he was spotted by a forest ranger by the name of Ralph Harris. As a forest ranger, he was expected to note the passing of all aircraft and his report was credible.

A few minutes later, Delta 673 was again spotted by two brothers named Ogilvie, preparing for the opening of salmon fishing season on 15 September. Their position was east of the small lumbering town of Plaster Rock. The weather in the area had improved since leaving the cloud and rain showers along the river. It was partly cloudy and warm in the Plaster Rock area that afternoon, typical of central New Brunswick for that time of year. Doan and Rennie continued on their way towards Grand Lake. Doan had flown over the area several times during his flying career and knew that he was entering a region almost devoid of suitable water landing spots. His only chance for a safe water landing would be at Beaverbrook Lake, which, at a mile and a half long, could easily accommodate the heavy Delta on floats. He would have entered this region with some trepidation, but full confidence in the continued performance of the engine. Otherwise, he would have turned back.

These sightings seemed to indicate that Doan and Rennie were on course and relatively on time for the big water of Grand Lake in south central New Brunswick east of Fredericton, where they were to make a left turn towards Shediac on the coast. However, the Delta was spotted again a few minutes later by a survey crew about 15 miles southeast of Plaster Rock. One of these men, a Mr. Castigan, stated that he heard the aircraft’s engine sputtering and missing. The flying distance between Plaster Rock and Beaverbrook Lake is approximately 25 miles. Despite what appeared to be engine trouble, Doan was nursing the engine and continuing on his way, perhaps to attempt a landing at Beaverbrook Lake, which was his best chance at about ten miles ahead. He never made it.

Shortly after being spotted by the men of the survey crew, Doan, Rennie and Delta 673 disappeared over the horizon and were never seen again.

In the early afternoon of 14 September 1939, in a low valley near Beaverbrook Lake, the heat was oppressive and the humidity high. The only sounds were the creaking pulley cries of blue jays, the buzz of cicadas and the hot wind in the tree tops. The reforested softwood evergreens shaded the valley floor where, twenty years before, the old growth had been felled and limbed. At precisely ten minutes after 1 p.m., the valley reverberated with the sputtering and coughing of a big radial engine in trouble overhead and then out of the hazy summer sky, a shadow and whistling sound flashed through the tree tops. A millisecond later, the heavy mass of a Northrop Delta cleaved the forest canopy, crashed through the foliage and slammed nose and floats first into the valley floor. The shriek of metal and the horrid, heavy crash lasted but seconds—instantly twisting and repositioning the parts of Delta 673 in a small area below a deep green canopy that closed over the metallic and human carnage. There was no fire or broken trees to mark the spot where it entered the forest.

Within a minute, all that could be heard was the ticking of the heat from the now dead engine, the drip of aircraft fluids and human blood. It is not likely that the two airmen inside survived the heavy impact, but their last sight as they held out their arms to protect themselves was most certainly the green treetops of a land few people ever walked through and the dark forest floor below. In a few minutes, the cicadas resumed their rattle and the blue jays shrieked their concern. The misshapen metal containing James Edgerton Doan and David Alexander Rennie would remain here unseen for nineteen more sweltering summers and eighteen hard New Brunswick winters.

In the first few weeks, it is likely that search aircraft overflew the spot or nearby Beaverbrook Lake where Doan and Rennie were so obviously trying to land, but there was no wound in the canopy to give away the end of two bright young lives. In a few days, the weather and the animals began to reduce the once-human contents held within the broken air frame. In a few months, the snow began to fall and the trees continued to grow and close over the violent place. The only witness to what happened here was the New Brunswick wilderness, and it would never tell the whole story.

When Doan and Rennie failed to show up at Shediac, the Royal Canadian Air Force was not overly concerned at first. Doan was an experienced pilot and the Delta was equipped with floats. It was very likely that he had made an emergency landing of some sort on lake or river under his flight path or perhaps in Northumberland Strait, the body of water separating New Brunswick from Prince Edward Island.

The next day, 15 September, it was Vera and Ted Doan’s fifth wedding anniversary, the birthday of Rennie’s mother Isabella, and the two Ogilvie Brothers had begun their salmon fishing season near Plaster Rock. By now, there was concern about the fate of the two men and Delta 673, and telegrams were sent to Vera as well as Rennie’s parents.

It is always sad to hear of the small bits of their ongoing lives that were unfolding when they got the news. Isabella Rennie had just that minute told her neighbour that she was surprised that she had not heard from her son on her birthday, something he had always done. In the next moment the Canadian Pacific Telegraph delivery boy wheeled up on his bicycle.

Vera Doan had just finished baking a sheet of cookies when the doorbell rang. Vera’s telegram stated:

SYDNEY NS

REGRET TO STATE THAT YOUR HUSBAND DEPARTED FROM MEGANTIC PQ IN DELTA AIRCRAFT SIX SEVEN THREE ON FOURTEENTH—FOR SYDNEY NOVA SCOTIA AND HAS NOT BEEN SEEN SINCE. FIVE AIRCRAFT OF THIS SQUADRON EMPLOYED ON SEARCH OF AIRCRAFT

OC NO 8 GP SQUADRON.

The initial stages of the search involved flying the planned route of Delta 673, looking for the big aircraft on lakes, ponds and rivers and checking for smoke or any visual signs of the missing aircraft. RCAF personnel visited or telephoned various official agencies in the search area looking for details or reports of the aircraft. These included RCMP detachments, RCAF stations and outposts, forestry agents and logging companies. During these interviews, the aforementioned sightings by Corporal Arsenault, Atkinson, Harris, Castigan and the Ogilvie Brothers came to light and gave searchers a general sense that Doan and Rennie had been in the Edmunston/Plaster Rock area in the early afternoon of 14 September.

The search continued for weeks, but nothing was ever found. The RCAF worked with aircraft from the Department of Transport as well as the Irving Oil Company, but nothing was turned up. The RCAF dismissed the report by Castigan and the survey crew, despite the fact that there were a number of men in his party. Instead, they focused on another witness, a Mr. Levesque, who said he saw and heard an all-metal monoplane aircraft near Saint-Joseph in the Green River Lakes area, which was much farther north. He stated that he heard it making noises that indicated the pilot was having trouble with the engine. This report was more than 100 kilometres northwest of the actual site of the crash. In believing Levesque’s report that the engine was making “sputtering noises”, the RCAF began to think that the aircraft would be found in this area and focused their attention there. They rightly felt that Doan would not have pushed on for another 100 kilometres if he was experiencing engine trouble. There was also an erroneous report of an aircraft heading east near Upper Blackville on the Miramichi River. If believed, this would indicate that Doan was closing in on the coast, possibly near today’s Kouchibouguac National Park. Both of these erroneous reports had the searchers looking in the wrong places.

When the leaves fell off the deciduous trees in the middle of October, they were able to see through to the ground, but still nothing was spotted. The RCAF continued to search until the end of October, but no sign whatsoever of Delta 673 was ever found. It was thought that Doan and Rennie had crashed in heavy coniferous bush that would have covered the site, or had flown out over the ocean and had landed in the sea, only to be swamped by heavy seas. The fact that nothing would be found for nearly two decades let the RCAF to settle on the latter scenario as most likely.

The fate of Doan and Rennie would remain a mystery for 19 years. These two young airmen would become the very first Royal Canadian Air Force casualties of the Second World War and the first of 809 Commonwealth airmen and airwomen whose names are on the Commonwealth Air Forces Ottawa Memorial. The Ottawa Memorial commemorates 809 men and women of the Air Forces of the Commonwealth who lost their lives while serving in units operating from bases in Canada, the British West Indies and the United States of America, or while training in Canada and the U.S.A., and who have no known graves. That’s 809 men and women who simply disappeared while training or serving and were never seen again.

Finally Found

In July 1958, in the middle of yet another hot and humid central New Brunswick summer, crews of the J.D. Irving forestry company were surveying and building a new logging road through the area around Beaverbrook Lake where they had recently purchased the logging rights. It would soon be time to harvest the second growth softwood forest in the area. A company aircraft was employed to scout ahead of the survey team for major impediments to road building such as ponds, ravines and streams. While checking the proposed route, the pilot saw sunlight glinting off of something metallic and shiny deep in the forest. Despite circling the object he could not determine what it was, only that it should not be there, 18 miles from the nearest sign of civilization. The pilot guided the two men of the road survey crew, Frank Barkhouse and Charlie Grey, towards the spot.

A screen capture from Google Maps of the area of New Brunswick with Beaverbrook Lake at the centre. It was just northeast of the lake where Doan and Rennie met their deaths. Other than a small cottage or rest area at the eastern end of the lake and a small forestry barracks facility a couple of kilometres down the road, there are no other places of human habitation for many kilometres in every direction. Today, the area is veined with logging roads and patched with clear-cuts and tree planting and to the southeast there is now a single paved runway called Clearwater Aerodrome. The strip, owned by J.D. Irving Woodlands, services the forestry industry and can be used for fire fighting aircraft. Photo via Google Maps

It was here, just a short distance from Beaverbrook Lake, that the remains of Delta 673 were finally found—nearly nineteen years after it went missing. Amidst an area of softwood trees Barkhouse and Grey found the wreckage of an all metal monoplane on floats. It was clear that the aircraft had impacted the earth almost vertically, for the wreckage was in a compact area and there were no indications of trees that had been broken or knocked down by the impact. There was no evidence of any skeletal remains in or around the cockpit. The men remained at the site only briefly and then trekked out of the bush and headed to Juniper some 18 miles (30 kilometres) to the southwest to report their findings by telephone to the RCMP and Stuart Cougle, the local Forest Ranger.

The next morning Cougle and Corporal Ron Rippin drove to Juniper and collected the two men of the survey crew and drove back to Beaverbrook Lake to inspect the wreckage. The men made a much closer and more detailed inspection of the entire site and collected a few objects to assist them in identifying the aircraft and its last occupants—a wallet, belt buckles, a piece of an Ottawa newspaper dated 13 September 1939, brass buttons, metal components from parachute harnesses, a camera and untouched rations. They also found the partial remains of a suitcase with the monogram D.A.R. imprinted on it, a razor, a flashlight, a bayonet and some loose change.

Unfortunately, the media got wind of the story of the mysterious wreckage of an old RCAF aircraft in the woods of New Brunswick and it was broadcast with the radio news across the country. Before it could be confirmed as the remains of Delta 673, both Vera Doan and Rennie’s sister heard about the discovery and knew in their hearts it was the Delta their loved ones had been piloting. The RCAF thought it likely that this was Doan and Rennie’s aircraft, but needed to officially verify that this was the case. They assembled a search and investigation team at RCAF Greenwood and four days after the wreckage was spotted, they were flown to Beaverbrook Lake in a deHavilland DHC-3 Otter of No. 103 Rescue Unit, piloted by Flying Officer Patrick Donaghy who happened to be in Greenwood providing float training.

On 14 July 1958, four days after the discovery of the wreck, the Royal Canadian Air Force sent a ground party to investigate the site. They were flown from RCAF Station Greenwood, Nova Scotia in a de Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter of the famous No. 103 Rescue Unit piloted by Flying Officer Pat Donaghy (at left in this period photo). Squatting next to him on the Otter’s float are members of the ground party, all members of the RCAF. Left to right: Flying Officer M.G. Cloutier, Corporal J.R. Lemieux, Sergeant Robert Crebo and Corporal William Armstrong. The photo was taken at Third Loch Lomond Lake, on 16 July 1958. In an eerie coincidence, the RCAF serial number for the Otter was 3673. Photo via Pat Donaghy, RCAF retired

The men spent several days searching the wreckage carefully as well as the surrounding area, but found little to add to the story, except the precise time of the accident which was registered by the stopped aircraft clock. In a letter to Vera Doan in 1958, Air Vice Marshal J.G. Kerr noted the tally of personal effects found at the site, which was very little: “sun glasses, wallet, piece of shorts, piece of air force shirt, buckles from parachute, razor, newspaper, watch belonging to Rennie stopped at 1310 hrs also, a/c watch stopped at same time, rubber mitts with Doan’s name, anchor rope, a/c emergency ration unopened and well preserved”. No human remains were found during the RCAF’s search, but a short time later, Dr. John Lockhart, a local physician and pilot from Bath, New Brunswick on the Saint John River, flew his Republic Seabee into Beaverbrook Lake and hiked to the site. He was looking specifically for human remains and found skull fragments inside the cockpit area, which led to the conclusion that the two men were killed upon impact.

First of a series of photographs taken at the crash site by the RCAF search team after its discovery in July of 1958. One can see why it took so long to find the remains of the aircraft. The densely forested and remote location had shrouded the wreck for nearly 19 years. In this photograph, the propeller blade is bent backward. This gives us information about the last seconds of the flight. During a crash of a propeller-driven aircraft, the blades will bend backwards if the engine is at idle or has failed. If they are bent forward, this would indicate the aircraft was under power. It appears that Doan had either a dying engine or had cut the power moments before impact. Photo via Pat Donaghy, RCAF retired

This photo of 673 shows the compact grouping of wreckage, suggesting a near vertical impact with minimal damage to the tree canopy—a scenario that would keep the site from the eyes of search planes and other flyers for almost 19 years. Photo via Pat Donaghy, RCAF retired

The upside down cockpit of Delta 673 with control wheel and rudder/brake pedals visible as well as instruments and throttle, mixture, prop, and cabin heat quadrant at bottom (this was affixed to the top of the control panel between the two cockpit seats). It is sad to think that Doan’s and Rennie’s bodies had lain here undetected for so long. Photo via Pat Donaghy, RCAF retired

The rear fuselage and empennage, not severely damaged, but collapsed following impact. The all metal aircraft had very little in the way of markings, just roundels and the three-digit RCAF serials (underwing and on aft fuselage). Despite 19 years in the elements, these remained largely intact. Photo via Pat Donaghy, RCAF retired

The port side of the fuselage with wing centre section at top. Photo via Pat Donaghy, RCAF retired

The remains of the main fuselage section of Delta 673. In the foreground lies a crumpled wing section with underside upwards showing the improvised bomb racks that were added to the Delta in preparation for its new role as anti-submarine aircraft. Photo via Pat Donaghy, RCAF retired

A close-up of the underside of Delta 673’s wing showing her modified bomb racks which can be seen in the wreckage at the bottom centre-right of the previous photograph. There are a number of images of 673 on the web showing her on skis at Rockcliffe with these bomb rack modifications. Perhaps she was the test aircraft for the concept. What damage these small bombs were expected to do to a submarine is not known. Photo via Pat Donaghy, RCAF retired

Epilogue

Ten years after the discovery of the remains of Doan, Rennie and Delta 673, the National Aviation Museum and the Canadian Forces had the wreckage of Delta 673 hoisted by Canadian Air Force helicopter from the valley near Beaverbrook Lake and prepared for transportation to its facilities in the old Second World War hangars at RCAF Station Rockcliffe where the National Aircraft Collection was housed at the time. The Museum curators wanted the wreckage for restoration as it represented the only extant example of the Canadian Vickers-made Delta, the first all-metal, stressed skin aircraft to be built in Canada as well as the first RCAF aircraft to be lost in the war. It is not clear why only the fuselage arrived and all else, including the troublesome engine, was lost en route. Memories are short and history seems to have covered this aspect as much as the forest covered up the wreckage for nearly two decades. Mystery still clouds the story.

In July of 1958, when Forest Ranger Stuart Cougle left with Royal Canadian Mounted Policeman Corporal Ronald Rippin to travel to Juniper, New Brunswick to interview the men who reported finding a mysterious crashed aircraft in the forest near Beaverbrook Lake, he left behind his ten-year-old son Jim, who had begged to join them. For a young boy growing up in sleepy New Brunswick in 1958, this seemed like the ultimate adventure, but for the agents of the government of Canada, this was a serious and possibly tragic situation that required a professional detachment.

Young Jim Cougle would grow up to be a historian of note in New Brunswick, author of several books on subjects pertaining to New Brunswick and Canadian history. In 2004, Jim Cougle published a small book or historical monograph about the story of Doan, Rennie and Delta 673. Mystery Plane Found in New Brunswick is a fascinating story with far more detail about the events, the airmen’s personal lives, the search and the possible reasons for the crash. It is written with great attention to historical accuracy and a tremendous amount of heart. It is clear that he was affected by the story as a young boy.

Two photographs of the rear fuselage of Delta 673 after its airlift from the New Brunswick bush in 1969, stored outside at the National Aviation Museum (now the Canada Aviation and Space Museum (CASM)). The aircraft was deemed an important relic at the time as it represented the first RCAF aircraft lost during the war, and the only “surviving” airframe of a Northrop Delta, the first all metal, stressed-skin aircraft type built in Canada. All of the wreckage had been brought out with the fuselage, but only the fuselage made it to Rockcliffe, with the rest being inexplicably lost. Now, the CASM has categorized the wreckage unrestorable due to the missing components and quite possibly because it is, in effect, a war grave. Photos via Canada Aviation and Space Museum

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, the author would like to thank James Cougle whose excellent monograph, Mystery Plane Found in New Brunswick, was the source of much of the material found in this story. Without Jim’s fine work, dogged research and clear passion for history and story telling, I would have little to report.

Secondly, thanks go to former RCAF pilot Pat Donaghy, who suggested this story to me, sent me Cougle’s monograph and original photos taken of the crash and ground party.

Thank you gentlemen.

Dave O’Malley