CIRCLE OF SORROW

The Alberta landscape is one of undulating and verdant beauty in the spring. To the west, on the distant horizon, stands the saw-toothed, snow-capped permanence of the Rocky Mountains, orange-flamed in the mornings, hazed and purple in the evenings. The wide, open valleys are peppered with herds of black cattle and frisking calves under an armada of arctic white cumulus, sweeping across the sky. Over the surface of the landscape, deep green shadows race with their cloud twins down valleys and bowls and up the far sides on their way to Saskatchewan.

Southern Alberta opens your heart, lifts a great weight from your shoulders and slows your breathing. It is the landscape of independence and self-reliance. For those who grew up here, but now live with a city crowding in on all sides, coming home to Southern Alberta is like being released from prison.

Today, it is largely a quiet place—just the lowing of cattle, the anxious shrill of the red-tailed hawk, the distant vulcanized hum of truck tires and guttural groan of engine brakes on Highway 2. But in the 1940s, the skies here thundered and clattered as yellow Harvards, Ansons and Airspeed Oxfords criss-crossed the vastness of the foothills. It was the time of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, and newly constructed training bases dotted the land where once only aboriginal hunters roamed—at Fort McLeod, High River, Vulcan, Lethbridge, Pearce, Claresholm and Medicine Hat. On sunny days, the skies were seamed with yellow aircraft flying off in every direction. Down low, exuberant young men hopped over wind breaks and farm houses in their Ansons, circling grain-elevators (with the names of towns on them) to get their bearings before thundering off to the next way point. Up high, formations of Ansons and Oxfords droned west and east like lumbering vees of giant geese.

With all its big-heartedness, endless vistas and chrome-bright days, it is an unlikely place to find a memorial to sacrifice and loss that can only be seen from aircraft or satellites. Yet, there it is.

On the southern Alberta prairie, just a few miles from the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, stands the tiny farming community of Cayley. With a shrinking population of less than 300 independent souls—Hutterite farmers, cowboys, truckers, retired couples and young families—Cayley can be easily missed. As you drive towards Cayley, heading south on the old Highway 2A, also known as Range Road 290, you pass pumpjacks nodding like dazed donkeys, gas pumping stations and massive cattle feed lots. The ground undulates away in every direction like a picnic blanket caught in a breeze. Out there to the left somewhere, about three kilometres north of town lies the art project/memorial known as Gravitas. Even if you were gazing straight at it from your moving car, you would likely miss it, for it seeps into the landscape rather than leaps from it.

A view of the small farming community of Cayley, Alberta, looking south along Highway 2A. Cayley was named after Hugh St. Quentin Cayley, the first publisher of the Calgary Herald newspaper. Photo: clogie@Panoramio

From a moving car, Gravitas looks more like some junked and rusting farm equipment than a tribute to the young airmen of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). From the air, however, there’s a quite different story. Gravitas takes the form of a 75-metre-diameter compass rose with the full-size planform outlines in prairie grass of twelve Avro Anson aircraft pointing inwards towards an open circle of prairie grass. Each of the twelve Anson shapes embraces parts of actual former Anson aircraft of the BCATP. The entire work is made from gravel and grass. It is designed to be consumed by the landscape that gave it birth.

A great shot of Gravitas and its relation to Highway 2A and the wetland sloughs. This photo was taken by a family in their homebuilt aircraft en route to a picnic in British Columbia—some of the few folks lucky enough to see it from the air in its springtime prime. Photo: AmateurBuiltFamilyFun.ca

The thought process behind this strangely hidden and quietly moving work of art is best described by its creator, Keith Harder of the Department of Fine Arts, University of Alberta:

“Gravitas is about the weight of time. It is also about the entropy of the material world, of memory, of dreams; how all such things go to ground; it is about death and dying. It is about excursion and return; of overcoming the forces of gravity and of adversity. It is about courage, about rising up and extending the horizon. It is about the birth of possibilities and living.

I have been working with the curator (Dave Birrell) of the Bomber Command Museum, on a series of art works based on a number of derelict aircraft from the era of the BCATP program. These few artifacts are some of the only palpable remainders of a galvanizing moment in the history of Western Canada; a time that was fraught with desperation and hope as well as romance and grievous tragedy. This moment produced stories where much of the mystery that comprises the human condition is condensed.

Related Stories

Click on image

In their current state these artifacts have little value beyond their use as reference material for aircraft restorers. But to say they have no value at all is to view any ruin from history, whether cathedral, castle or city, as merely rubble standing in the way of another condo project. Rather, all these things are a reminder of who we are, what we need to overcome, and to what we might aspire. It is my intention to arrange these artifacts in a setting that will stimulate such reflection and highlight these values. The Anson artifacts are emblematic of certain pieces of the past that are forgotten, repressed or seen as not useful. However, that past is still with us and deserves an accounting.”

Deteriorating hulks of Avro Anson training aircraft of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (like these in the winter of 2009) littered the farms and airfields of Southern Alberta. The Bomber Command Museum of Canada (BCMC), in Nanton, Alberta, made a conscious effort to collect up any remnants they could find and bring them together in Nanton. Without a place to store them, these old war horses would be exposed to the elements anyway, so when Keith Harder put together his plan for Gravitas, the folks at BCMC welcomed the project. Photo: Bomber Command Museum of Canada

A deteriorating Anson hulk is lifted from the Bomber Command Museum's storage yard at Nanton, Alberta. Photo via Keith Harder

The aircradt silhouettes were mapped out using pre-cut tarp templates. Photo via Keith Harder

Another hulk is lifetd from a flatbed truck at Cayley. Photo via Keith Harder

UTA Fight 772—Powerful Memories in a Desert Wasteland

On the other side of the world, in a landscape entirely different from Cayley, Alberta, stands another memorial which has many similarities to Gravitas. It is a memorial to loss, but it is also an astonishingly powerful statement that rails against depravity, terror and man’s own inhumanity.

Niger is one of the largest countries in Africa—bigger than Alberta and Saskatchewan put together. Eighty-five percent of Niger is covered by the South Saharan Desert—miles upon miles of unbroken wasteland, of undulating sand dunes and the unrelenting blowtorch of the sun.

It is a vast, trackless, forbidding and inhospitable skillet of heat shattered rock, washed and scoured by an ocean of acid yellow sand and gaseous shimmering horizons. Spend a few minutes on Google Earth to scroll across its interminable and tempered face and you will understand that this Ontario-sized torment holds the very minimum of life as we know it. It has more geologically in common with Mars than Earth. From above, there exists only an endless sea of shifting grit and sand with rocky and toxic-looking ulcerations erupting from its salty skin. There are no roads, no trails, few possibilities for sustaining human life without water and food. It is utterly heartless. Just sand and rock scrabble and heat and time. It does however have one thing in common with Cayley, Alberta—the fast disappearing memorial to the victims of UTA Flight 772.

At around two o’clock in the afternoon of 19 September 1989, amidst the searing heat and blinding glare of the sun, the spinning, whistling, shattered and smoking remnants of a McDonnell Douglas DC-10 rained down on a spot in this desolate wilderness—engines, magazines, passenger seats, luggage, cargo, landing gear and the broken remains of 170 human beings—54 French, 48 Congolese, 25 Chadians, 9 Italians, 8 Americans, 5 Cameroonians, 4 Britons, 3 Zairians, 3 Canadians, 2 Central Africans, 2 Malians, 2 Swiss, 1 Algerian, 1 Belgian, 1 Bolivian, 1 Greek, 1 Moroccan and 1 Senegalese. It was a scene of almost unimaginable horror and heartbreak. Perhaps it was good that there were no humans at this spot to witness this horror, but then, perhaps it is the greatest sadness of all that there were no humans to bear witness to the loss of so many. The nearest community was the oasis hamlet of Fachi, some 150 kilometres to the northwest.

UTA (Unions des Transports Aériens) Flight 772 was just 46 minutes out of Brazzaville, Congo’s N’Djamena Airport, bound for Paris, when a suitcase filled with penthrite exploded in the cargo hold and dispatched 170 innocent people to their terrifying deaths in a heartless land. The bomb was placed by members of Islamic Jihad and the Secret Chadian Resistance, supported by Libyan agents. To add another meaningless layer to the meaningless tragedy, the bombing was said to be revenge against France for allegedly supporting Chad against Libyan-supported rebellion in that state.

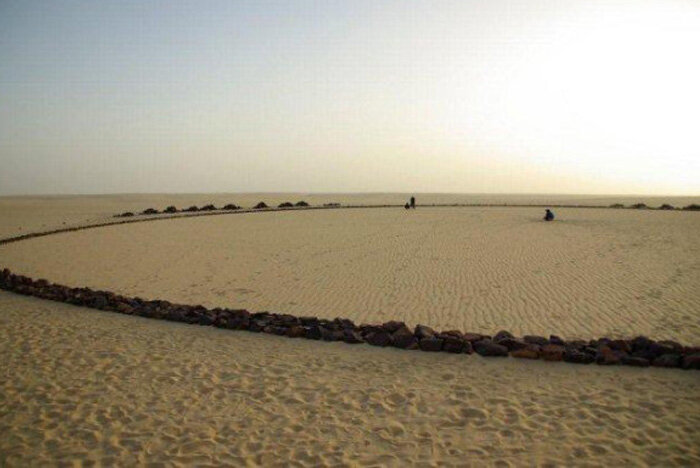

The families of the victims of UTA Flight 772 knew that the location of the tragedy meant few visitors would ever come, so when it came to creating a memorial, they decided that it would be something that could only be seen by God, fellow air travellers and the unjudging eyes of satellites. The memorial to the victims of Flight 772 is one of the most extraordinarily beautiful, meaningful and imaginative memorials to tragedy extant. Like the Gravitas memorial in Alberta, it was designed to be consumed by the landscape and then to be exposed again and again as massive waves of sand submerge it in slow motion—driven by the hot Saharan winds. Over the endless eons, it will disappear and reappear as wave upon wave of time washes over it.

The UTA 772 memorial was built approximately 10 kilometres from the actual crash site in order to preserve the sanctity of the spot where so much tragedy bled into the sand. The memorial has many things in common with Gravitas—both are circles (Gravitas is 75 metres in diameter and UTA 772 is 61 metres) and symbolize a compass, both are made from gravel or rock, both contain the full-size silhouette of an airplane (a DC-10 in the case of UTA 772), both can only be seen from above and both are regularly consumed by the world around them. The design of the UTA 772 memorial goes emotionally much deeper though. Around the perimeter of the design are 170 mirrors, each embedded into a slab of concrete, and then shattered to symbolize the destruction of the individual and his or her family. At the north point of the compass stands a wing tip from the DC-10, sunk deep into the sand, upon which are the names of all those who were murdered just 10 kilometres away.

In the heart of the memorial, black Saharan rocks, trucked from the Aïr Mountains, form the outline of a DC-10. From the back of the DC-10 three contrails representing the aircraft’s three engines give the impression that it is forever heading north-northwest towards the beauty of Paris, the City of Lights. The memorial is described by Design for Conflict Heritage (a website dedicated to memorials to tragedy and conflict): “The memorial, partly financed by a compensation fund paid to the victims by the Libyan government, was built by 100 people working largely by hand under the desert sun. A black circle of about 200 feet in diameter, created by placing stones on the sand, outlines the life-size silhouette of the aircraft. Around the circle were placed 170 broken mirrors—representing the victims—and arrows marking the different points of the compass. At the northern point, part of the right wing of the plane—found 10 miles away—has been driven into the ground, with a plaque commemorating the victims. The memorial reflects the need to leave a permanent trace of this tragedy, despite an inhospitable geographic condition. The aim is to build some kind of still frame visible virtually worldwide. However, the interest of this project lies not only in its architectural features, but especially in the painful participation process and collective commitment that produced it and which can still be found in the actions carried out by the Association. In addition to the desire to keep alive the memory in the international public opinion, the actions aim to offer moral, material and financial support to all the victims of attempts and their families.”