BOTTLE OF HEARTBREAK —The Story of Albert “Tiddles” Brown

Albert Henry Brown was born in Southend-on-Sea, Essex, on 26 March 1923. His father, and namesake, Henry, was a retired Petty Officer Stoker in the Royal Navy who had served in the Battle of Jutland, and his uncle was also a Royal Navy stoker. Growing up in a seaside town, with the family’s naval background, it was perhaps no surprise that, when war broke out, Albert would volunteer to join up, and his chosen service would be the Navy, in the form of the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) (Albert’s older brother William joined the police in 1940, a reserved occupation, although he too was allowed to volunteer and also served in the FAA and Combined Ops).

As with many British naval aviators, flying training was undertaken in the United States and Canada. Albert, amongst those who were to form 1830 Squadron of the FAA, trained on American T-6 Texan and Brewster Buffalo aircraft at Naval Air Station Pensacola in Florida, with various interludes back in the United Kingdom and also Canada. Somewhere along the way, Albert acquired the nickname “Tiddles”, although the reason for this remains a mystery.

We do know that Albert was able to return home in December of 1941 to see his family. As his brother wrote, “I will never forget that day in December, 1941, when my father, mother and I, saw my brother for the last time, leave Southend Victoria Railway Station to return to the Navy en route to Canada and America to complete his training as a fighter pilot in the Fleet Air Arm, never to return”.

Prior to his departure, the family bought a bottle of sparkling Albert Porte French wine (possibly chosen for its name), with which to toast his safe return.

Albert travelled to Canada, where he spent time visiting relatives prior to gaining his wings and his commission. In true naval tradition, it also seems he had taken to smoking a pipe!

Flying Training was completed at Brunswick, Maine, where the young pilots converted from trainers such as the North American Harvard and Brewster Buffalo (both in Pensacola) to the mighty Chance Vought Corsair. Known by some choice nicknames, not least the ‘Bent-winged Bastard from Connecticut’, the Corsair had been deemed at first unsuitable for carrier use by the US Navy and was therefore made available to the FAA. With wingtips clipped for hangar clearance on British carriers, adjustments to the landing gear to prevent excessive bounce and a redesigned canopy, this aircraft was to become one of the principal fighter aircraft of the Royal Navy’s Pacific Fleet and indeed that of the United States. In June 1943, 1830 Squadron was officially formed at Naval Air Station Quonset Point, Rhode Island, with Albert as one of its first 13 commissioned pilots. Interestingly, pilot Les Retallick, also of 1830 Squadron, was another Southend boy. In an environment where young men from all corners of the Empire were thrown together, Albert and Les had plenty in common and were known to have become good friends.

In the winter of 1941–42, nineteen-year-old Albert Henry Brown, wearing flight boots and navy issue clothing, relaxes at the home of his Canadian relatives in Canada. Photo: Phil Grimwade Collection

Albert, smartly dressed in Royal Navy uniform and great coat, at the home of relatives in Canada, poses with Aunt Nellie (right photo) and another relative, possibly a cousin, by the name of May (left photo). The author is not sure where in Canada these photographs were taken. Photo: Phil Grimwade Collection

Albert, looking dashing with his pipe, poses with Bristles, the family dog of Canadian relatives. Despite the mature look, Arthur was just 19 years old in the winter of 1941–42. Photo: Phil Grimwade Collection

Related Stories

Click on image

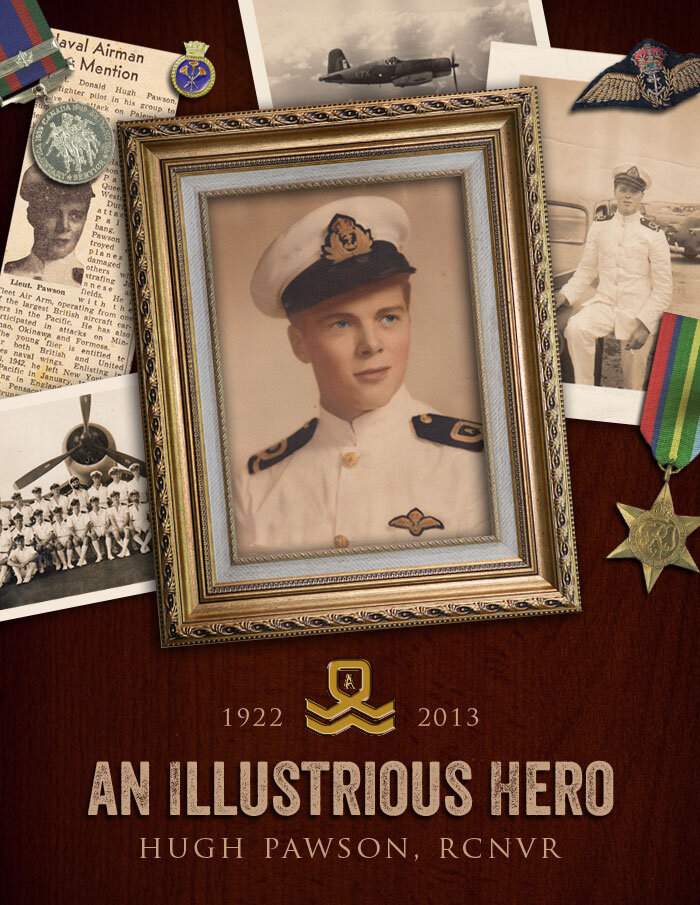

Young Albert Brown after getting his wings. Photo: Phil Grimwade Collection, tinting by Dave O’Malley

1830 Squadron travelled back to the United Kingdom with ten Corsairs aboard the Royal Navy Escort Carrier HMS Slinger, arriving in Belfast and then flew off Slinger to Royal Naval Air Station Stretton (HMS Blackcap) in Cheshire, England. They began working up on land with 1833 Squadron with which they would form No.15 Naval Fighter Wing.

Albert must have had a spell of leave in the late autumn of 1944 as he married Doreen in her hometown of Plymstock, Devon, UK. When he returned to his squadron, his new wife was pregnant with their son, Richard, born in June 1945 and never to know his father.

They landed aboard HMS Illustrious on 27 December 1943 before their full workup was completed and set sail for Trincomalee, Ceylon on 30 December 1943. Illustrious arrived in Trincomalee’s harbour on 28 January 1944, and spent the next few months training her new air units. During this period, Illustrious and 15 Naval Fighter Wing participated in several sorties with the Eastern Fleet searching for Japanese warships in the Bay of Bengal and near the coast of Sumatra.

Albert landed aboard the escort carrier HMS Slinger for the Atlantic Crossing, flying off at Belfast. Photo: Royal Navy

Albert landed aboard the escort carrier HMS Slinger for the Atlantic Crossing, flying off at Belfast. Photo: Royal Navy

Another photograph from the same sitting as the previous shot shows 30 pilots of the 15th Fighter Wings of the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm at Surabaya. Albert sits second from right in middle row. Mike Tritton, the Wing’s new Commander sits dead centre. The pilots in the Wing group photo are as follows: Back row: Harry Whelpton, Reg Shaw, Matt Barbour, Tony Graham-Cann, Jock Fullerton, R. Quigg, Steve Starkey, Pete Richardson (wing observer), Jake Millard, Eric Rogers, Hugh MacLaren, Colin Facer, Stan Buchan, Gord Aitken, Moe Pawson; Middle row, seated: S. Seebeck, Johnny Baker, Alan Booth, Bosh Munnock, Norm Hanson, Mike Tritton, Bud Sutton, Percy Cole, Don Hadman, Albert “Tiddles” Brown, Les Retallick (another Southend boy); Front row, sitting on deck: Neil Brynildsen, Jimmy Clark, Mike Ritchie, Brian Guy. Photo via Pawson Family Archive

A close-up of the previous photograph—Albert “Tiddles” Brown is second from right in middle row, while Vintage Wings of Canada’s own Hugh “Moe” Pawson stands at right. Photo via Pawson Family Archive

A gorgeous photograph of an 1830 Squadron Corsair overflying China Bay (which actually lies to the left of this photo) near the important northeastern port city of Trincomalee, Ceylon in December of 1944. The spit of land that juts out into the Indian Ocean is the site of Fort Frederick. Prior to the Second World War, the British had built a large airfield to house a permanent RAF base called RAF China Bay along with a fuel storage depot and support facilities for the Royal Navy. The Royal Navy’s base there was called HMS Highflyer. After the fall of Singapore to the Japanese, Trincomalee became the home port of the Royal Navy’s Eastern Fleet. Photo via Pawson Family Archive

Palembang, Sumatra

On 24 January 1945, Albert and his colleagues were briefed for their part in Operation MERIDIAN—the attack on the oil refineries at Palembang, Sumatra, deemed essential to the Japanese war effort. The 1830 Squadron pilots were to fly ‘Ramrod’ missions—ground attacks on Japanese airfields protecting the refineries, destroying enemy fighters on the ground. Amazingly, this photograph shows the pilots discussing the mission just prior to taking off. Albert Brown stands at centre-left with hands in the pockets of his flight jacket.

1830 Squadron pilots mill about the deck of HMS Illustrious prior to a launch. Left to right: Eric Rogers, Les Retallick, Albert “Tiddles” Brown, Alan Broth, Mike Tritton, Hugh Pawson, Bosh Munnock (cut off in this shot.) Mike Tritton was Lieutenant Commander (acting) AM Tritton, DSC, RNVR who commanded the squadron for all of its operational life aboard Illustrious—from December 1943 to July 1945. Photo via Pawson Family Archive

The Palembang mission was a success, in no small part due to the suppression of enemy fighters and their destruction on the ground, with 34 enemy aircraft destroyed. There were, of course, casualties—in all a loss of seven pilots of whom my Great Uncle Albert was one.

“Bud Sutton [RCNVR] and ‘Tiddles’ Brown, of 1830 squadron, had been killed over airfields whilst ground-strafing…Brown had been hit fair and square by flak as he went into a strafing run and had cartwheeled through a line of Jap fighters drawn up on the runway. The poor chap was probably stone dead as he crashed through them at 300 knots.” [1]

Aftermath

Albert’s death had a profound effect on his family, to the point that his mother refused to accept it and would not allow his name to appear on the Roll of Honour at his former school. It was added after she died in 1951. He is also remembered on the Roll of Honour in Prittlewell Priory in his hometown of Southend and on the Fleet Air Arm Memorial, Lee-on-Solent.

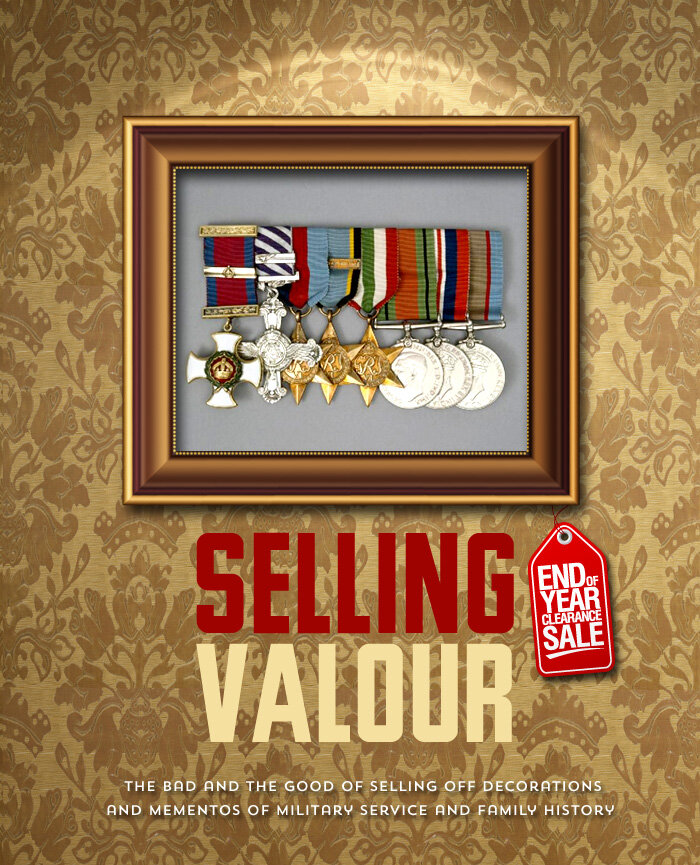

Doreen lost contact with her extended family and remarried. She is believed to have died in 2011 or 2012, when Albert’s medals appeared on an auction site. They would have been sent to her posthumously and she kept them for the rest of her life. The medals sold to an unknown collector and, despite my best efforts, I have been unable to trace them in the hope of bringing them back into the family.

Albert’s campaign medals were sent to his widow after the war—War Medal 1939–1945, Burma Star with Pacific clasp, 1939–45 Star, Atlantic Star. Ribbons behind are out of order, L-R Atlantic Star, Burma Star, 1939–45 Star, and War Medal. They were sold upon her death and a collector purchased them on eBay. The author would like to purchase them and bring them back to the family. If you know of the whereabouts of these family treasures, contact us.

William Brown, my grandfather, rarely spoke of his brother but kept the photographs he had. When he died in 2013, something very special came into my possession, which had been kept since that fateful day in December 1941 when the family waved Albert off at the station—the unopened bottle of Albert Porte wine. To me, this is a priceless thing, kept safe for 75 years. It is a true family heirloom, not because it has any particular value, but because of its story. To be opened on Albert’s safe return. Now to remain sealed forever

The bottle of Albert Porte sparkling wine, unopened since December 1941. Photo: Phil Grimwade

And Then...

Albert was an elusive figure to me. Of course, we had never met, but he was someone I felt I should know more about. He had almost become romanticized—a good looking boy, fun loving, with an eye for the ladies, who went to war but never returned. His brother, my grandfather, had his own very personal reasons for not talking about him, but surely with today’s technology I could find out more. I didn’t want him or his story to be ‘lost’. A combined love of aircraft, family history and military history got the better of me.

I finished work one evening, sat at the computer and went in search of Albert. I’d like to think I’d made myself a pink gin (a naval officer’s drink!). It’s not unlikely. I happened upon the Vintage Wings site and was amazed to discover some first-hand accounts of the Palembang raids, followed by some photographs. There he was! Photos I had never seen before, that I would never have believed existed, and an informative piece by Dave O’Malley about his aircraft, his ship, his squadron and his friends and colleagues. I made contact with Dave and suddenly Albert was a tangible figure, a young man who volunteered to fight, but never came back. An all too common story perhaps, but one that belonged to my family. It seemed that the circle had been squared, no longer the grief at his death but the pleasure of knowing how he had lived.

The strangest thing of all didn’t dawn on me immediately, as I sat reading, then emailing, to bring Albert back to life. The date was 24th January 2015, exactly 70 years after the Palembang mission.

Phil Grimwade

Hucknall, Nottinghamshire, UK, 8 January 2016

[1] Norman Hanson, Carrier Pilot, Patrick Stephens Ltd, ISBN 0 85059 349 2, 1979, p. 205